Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

WHISTLE-STOPPING Through Ohio by RICHARD O. DAVIES |

|

Ohio played an important role in returning Harry S. Truman to the White House in 1948. Prior to the election he had been foredoomed to defeat by all reputable political seers. Ohio was seen as being safely within the Republican fold, and was supposedly prepared to take part in a nation- wide Republican blitz. Elmo Roper, for example, quit taking samples of voter preference as early as September 9, with the comment that only a "political convulsion" could prevent New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey from winning the presidency.1 The prognostications were ignored by the voters, however, as Truman executed the most startling upset victory in the history of American presidential elections. Ohio went Democratic by over seven thousand votes, while Truman was returned to the White House by a popular-vote margin of over two million. In the electoral college he scored impressively with a 303-189 margin.2 NOTES ARE ON PAGES 196-197 |

114 OHIO HISTORY

Election analyst Samuel Lubell explains

the Truman victory as a result

of the "Roosevelt Revolution."3

The New Deal, creating a Democratic

majority in the nation's electorate, was

the major factor which enabled

Truman to coast to victory. Lubell

insists that the real surprise would have

been a Dewey victory; in fact, had the

turnout of voters been larger, "Dewey

would have been buried in a landslide."4

Even Henry Wallace, with his

1,157,000 popular votes, and Strom

Thurmond, with his thirty-nine Dixie-

crat electoral votes, failed to derail

Truman.

If Lubell is correct, how do we then

evaluate the campaign? To Lubell,

"often the campaign oratory is but

the small talk which conceals the almost

instinctive predispositions which all of

us carry in the backs of our minds.

Certainly no basic reshuffling of party

alignment is possible unless the sub-

conscious, emotional loyalties of the

voters are reshuffled."5 Applying this

idea specifically to Ohio, can we

relegate the Truman whistle-stop journey

through the state to

"small-talk"? Would Truman have won Ohio had he

not waged a strenuous campaign for the

Buckeye vote? Is it not possible

that such a campaign is necessary in

order to remind the voters to be certain

to vote in order to take advantage of

this party domination? Or, is it not

equally possible that such a campaign is

necessary, even vital, to reaffirm

the "almost instinctive

predispositions" of each voter? In other words,

would the 1948 voter have remembered the

New Deal if he had not been

reminded of it?

By examining closely the Truman campaign

in Ohio it is possible to

understand more fully the 1948 election

as well as obtain a detailed view

of a limited but significant part of one

of the most intriguing campaigns in

the nation's history. And, perhaps, such

an examination will suggest that

the whistle-stop campaign was of signal

importance in the election of

Truman.

In view of the supposedly overwhelming

odds facing Truman in Ohio,

it is surprising that he even bothered

to campaign in the state at all. In

1944 Dewey had won the state by almost

twelve thousand votes, defeating

Franklin D. Roosevelt and his relatively

unknown running mate in the proc-

ess. With a hard core of Dewey strength

theoretically already in existence,

there seemed to be little doubt about

Ohio's intention in 1948.6

Although all political experts believed

that "Truman had his back to

the wall" in Ohio,7 the

determined Missourian waged a whistle-stop cam-

paign into the heart of the state on

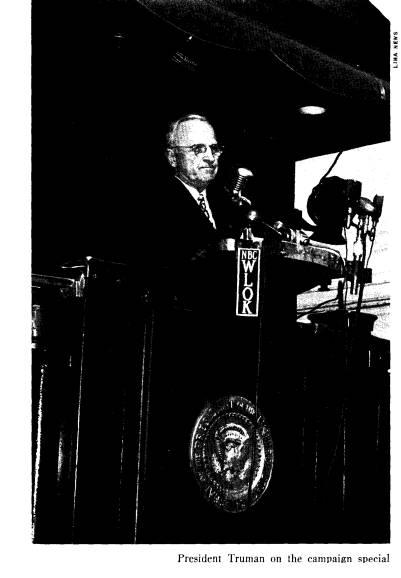

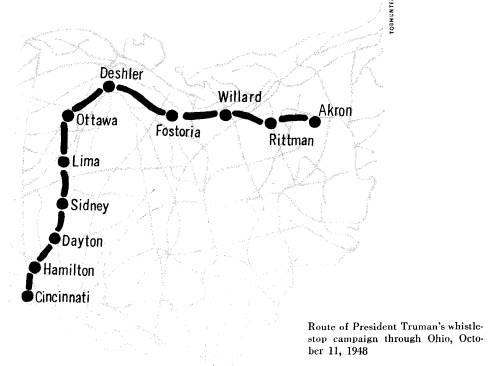

Monday, October 11. Beginning with

a breakfast speech in Cincinnati and

ending with a state-wide radio broad-

cast from Akron that evening, Truman

covered three hundred miles and

delivered eleven speeches. In the

process, he was cheered by several hundred

|

WHISTLE-STOPPING THROUGH OHIO 115 |

|

|

|

thousand persons; ominous predictions of a Republican romp notwithstand- ing, Truman did not concede a single vote, at least not until he had "told the people the facts."8 The Truman strategy in the Buckeye state, as well as throughout the nation, was not complex. It aimed to achieve two basic objectives, both of which Lubell uses as the key to his interpretation of the election: (1) to get out the vote in order to take advantage of the Democratic preponder- ancy, and (2) to speak clearly on a few easily understood issues which would make the Republican party appear to be the lackey of "big business" and "the vested interests," while at the same time extolling the Democratic party as the "party of the people." In order to accomplish this Truman followed the counsel of Democratic National Committee Research Director William Batt, who suggested in a memorandum to the Truman campaign advisors that in order for Truman to reinvigorate a party split by internal squabbling, the president "should not just exude confidence, but confidence with reasons. He should give our side some good solid substance upon which to hinge the campaign arguments. Platitudes and truisms should be avoided like the pox." And, to take advantage of Truman's homespun midwestern qualities, Batt urged that the wording of the speeches "should be short, homely, and in character. This is no place for Churchillian grandiloquence," he said.9 |

116 OHIO HISTORY

As a result, throughout Ohio as well as

the nation, Truman addressed

himself directly to the labor and farm

blocs, pointing out the advantages of

past Democratic rule. "The

Democratic Party thinks in terms of doing

things for the people--higher

wages--broader social security--protection

in old age--better schools and

homes--and a better life for the men and

women who do the world's work," he

told the Ohio voters.10 While describ-

ing his own party in the meaningful

terms of the New Deal and Franklin D.

Roosevelt (a vote-attracting name which

he did not hesitate to invoke),

Truman placed upon the Republicans the

stigma of depression, and declared

that the opposition party was controlled

by "special interests" which acted

only "at the behest of the

lobbies." Having drawn the images of the two

parties in such black and white terms,

Truman then exhorted his audiences

to "think it over when you go into

the voting booth next month. Think of

the gains you've obtained in the last 16

years--higher wages, social security,

unemployment compensation, federal home

loans to save your homes, and

a thousand other things--and then think

of the Tafts and Tabers."11

Thus the issues discussed by Truman were

those which would appeal

mostly to the middle and lower income

groups. Not afraid to tell his

audience to "vote in your own

interest," he put the campaign upon an

individual level; he simply said that

the working man and his family would

benefit more from his administration

than from that of the Republican

candidate. Bidding for the vote of

organized labor--or at least attempting

to keep it within the Democratic

fold--Truman declared that the Taft-

Hartley act, enacted by the Republican

eightieth congress, had "put the

handcuffs on labor."12 He

told city dwellers that their acute housing prob-

lem was the result of the refusal of the

"do-nothing eightieth congress" to

enact the comprehensive housing bill

which he so ardently championed.

In Dayton, for example, he reminded the

citizens that they had twelve to

fifteen thousand familes living in

substandard homes. "I have been trying

for over three years to get the congress

to pass the kind of housing laws we

need, but the Republican leaders in

congress are now more interested in

what the real estate lobby says than

what the people of this country need."13

He emphasized time and again the rapidly

rising prices and, naturally, laid

the responsibility at the feet of the

opposition: "You know that the Repub-

licans said if we got rid of price

controls, prices would adjust themselves.

Well, they have. They have gone clear

off the chart."14 On taxes, he told

his listeners, the Republicans

"delivered to the rich by passing a rich man's

bill."15 As for the

farmers--traditionally Republican in their politics--

Truman simply reminded them of their

remarkable gains in income since

1933: "Under the Democrats you are

getting a fair share of the whole

WHISTLE-STOPPING THROUGH OHIO 117

country's prosperity. Our federal farm

program is based on a solid truth--

farmers have a right to be sure of a

market for their products at good

prices."16

Because of these facts, Truman

explained, the Republicans did not want

to face "the issues." If the

Republican candidate refused to answer his

challenge, everyone could clearly see

that the Republican leadership was

out to destroy the gains made by the New

Deal. The reason why Dewey did

not speak out was clear--his party's

record was too weak on the major

(Truman-selected) issues. In Hamilton,

for example, Truman berated his

opponent for remaining upon a

supercilious plane, blandly calling for

"national unity" but never

getting down to "the facts." "This campaign

is . . . a crusade to enable the people

of the United States to realize what

this election means. I must face you

personally, or you don't find out.

That's what I'm doing. My Republican

opponents don't discuss the issues.

They are trying to make you believe

there are no real issues," he said.17

In addition to the big

"issues," the veteran campaigner from Missouri

knew the effectiveness of references to

items of local interest. In Dayton he

told his audience that if Daytonian

James M. Cox had been elected president

in 1920, "we never would have had .

. . that boom and bust program which

followed the election of a Republican

candidate."18 In Sidney, recalling his

senatorial committee which investigated

war production, Truman said he

had heard a lot about the war effort in

Sidney. "Sidney has elbow grease,"

he told the crowd, "and we need

this for continuing prosperity."19 In

Rittman, having been presented with a

block of locally produced salt, he

responded with a ready quip; "And

don't think I'm not going to put it on

the tail of the opposition."20

At Fostoria he used the time-tested political

device of praising the virtues of small

town and farm life. Referring to a

recent sarcastic remark made by Robert

A. Taft that "Truman is hitting

all the whistle-stops," Truman

retorted that such towns as Fostoria "are the

backbone of America." And, too, he

was careful to point out that as an

ex-farmer, he had observed from his

train window that Ohio's farm land

appeared to be the "finest in

America," and was, in fact, "almost as good"

as that back home in Missouri.21

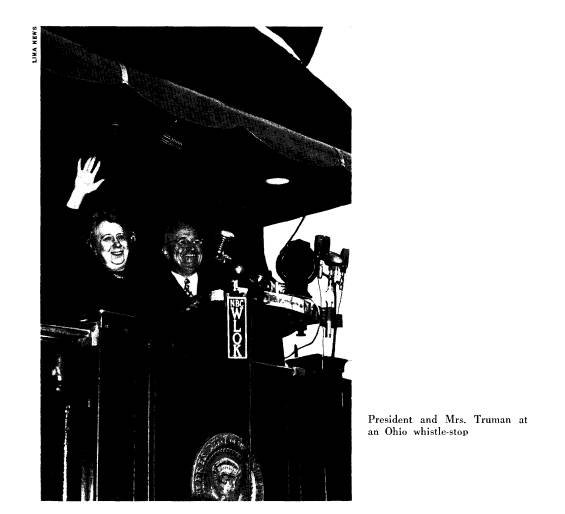

Throughout the trip Truman cast down

from the train platform an image

of honesty, sincerity, and simplicity.

This image was further enhanced

by the presence of his wife and daughter

Margaret on the train platform

with him. Here was a man of humble

origins who was not only the leader

of his people but one of them as well.

He was not afraid to trust the judg-

ment of the "people," for he

knew them well from his own Missouri back-

ground. He knew well those who gathered

excitedly around the rear of the

|

|

|

train to catch a glimpse of the president. His ability to reach them was not an unimportant aspect of this trip. "He's the President," a Lima News editorial writer observed, and yet, "he's just an ordinary family man, proud of his wife and daughter. He has something in common with many who heard him."22 Although the Ohio campaign on October 11 would be considered "very successful" by state party leaders,23 it could hardly have begun upon a more dreary note. Arriving in Cincinnati at 7 A.M. on a rainy Monday morning, the president's motorcade from Union Terminal to a Netherland Plaza breakfast gathering of about two thousand Democrats drew just a few hundred spectators. Only scattered clusters of early risers lined the "almost deserted" streets, braving the chilling light rain, as the presidential entourage quickly passed by.24 With no cheering crowd to welcome him to a state he knew he had to win, and with a bleak, grey sky threatening |

WHISTLE-STOPPING THROUGH OHIO 119

to dampen the day's all-important bid

for votes, Truman's spirits visibly

sagged. A veteran political reporter for

the Des Moines Register, who had

traveled with Truman throughout the

campaign, noted that "he looked like

a man who had received bad news but felt

the show must go on."25 At the

hotel, however, where he was introduced

to the assembled Democrats by

Mayor Albert Cash as "a leader of

unflinching courage,"26 Truman re-

sponded with one of his typical

speeches--he vigorously attacked his

opponent. Dwelling upon the theme of

Dewey's refusal to discuss the issues,

Truman noted that while he and

Cincinnatian Robert A. Taft were "as far

apart as the poles on the welfare of the

people, at least you know where

Taft stands, and that is more than you

can say for some Republican candi-

dates." Continuing this line of

attack, Truman said, "You know where I

stand. We are just trying to find out

where the other fellow stands." Turn-

ing to his favorite whipping boy, the

eightieth congress, he charged that

its Republican majority leadership had

"led the fight against price controls"

and "consistently opposed a

national health program" while supporting

"measures which took social

security away from a million people."27

At nine-thirty the president, with his

family, advisors, and a host of Ohio

Democratic candidates headed by

gubernatorial candidate Frank Lausche,

boarded the chartered train and headed

northward. Stopping at industrial

Hamilton at 10 A.M., Truman was greeted

enthusiastically by a crowd

estimated at ten thousand persons.28

The rain had stopped and a brisk

autumn breeze whipped around the train's

rear platform as the Democratic

candidate, obviously very much pleased

with the large crowd, stepped for-

ward to deliver a ten-minute speech on

the evils of Republican congressmen.

The unexpectedly large crowd quickly

restored Truman to his usual fighting

self and erased all thoughts of the

sparse crowd in Cincinnati. It produced

"the most striking change in the

Democratic candidate's demeanor I have

witnessed in all of our trips,"29

the Des Moines reporter observed, as

Truman, making a "natty

appearance" in his blue pin-stripped suit,30 lashed

the Republican congressional leadership

for its dilatory action on the bi-

partisan Taft-Ellender-Wagner housing

bill.31 Explaining in oversimplified

but politically effective terms the

reasons why the comprehensive housing

bill was not enacted despite the

greatest housing shortage in the nation's

history, Truman charged that "they

killed the housing bill at the behest of

the real estate lobby." This was,

he concluded, just one of several reasons

why the Republican candidate did not

desire to discuss the issues.32

By eleven-thirty the diesel-powered

train had arrived in Dayton, where

Cox and Mayor Louis W. Lohrey were at

the station to welcome the presi-

dent to the Gem City. Because he had

arrived during the lunch hour, and

|

120 OHIO HISTORY because the city schools had been dismissed to allow the students to see the president, a very large, excited crowd lined Main Street as Truman and his family were driven to Memorial Auditorium, where he delivered a thirty-minute speech. An estimated fifty thousand persons had gathered along the route to the auditorium, and amid the carnival-like atmosphere that prevailed on a "no-school" day, a young schoolboy, his political symbols slightly confused, was heard to ask, "I wonder if he will ride in on a mule?"33 Truman might not have arrived upon a mule, but he certainly was figuratively astride the Democratic donkey as he opened fire upon the "do- nothing eightieth congress" for opposing all effective price controls. Ob- serving that the "boom and bust" economics practiced by the Republicans had led to the Great Depression in 1929, he pointed out that "they still refuse to give us the protection we need against another crash."34 Turning to housing, he said that when he had given them an opportunity to enact the housing bill in his special session of congress in July, the Republicans had refused to comply.35 |

|

|

WHISTLE-STOPPING THROUGH OHIO 121

Leaving a cheering crowd at the station,

the train continued its northward

journey, making a five-minute stop at

Sidney, where he urged, as he did at

every city visited, the election of

Lausche and local Democratic congress-

ional candidates. "Vote the

straight Democratic ticket, and you vote against

special interests," he said.36

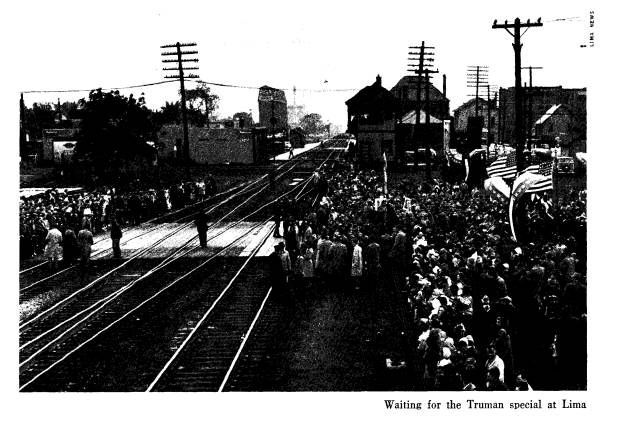

Arriving at 2 P.M. in Lima, which is

centered in Allen County's rich

farming area, the apparently tireless

sixty-four-year-old campaigner re-

minded a gathering of over four thousand

how the New Deal had revived

the national economy after the

depression. Since Franklin D. Roosevelt

had taken office, he pointed out, farm

income alone had increased over nine

times. To insure continued prosperity,

he said, his reelection was im-

perative.37

From Lima the train moved on to Ottawa,

Deshler, Fostoria, Willard, and

Rittman for short stops as it headed

towards Akron. At each stop Truman

spoke in generalities about farm prices,

inflation, and housing, always con-

cluding with his own practical bit of

advice: "Vote in your own interest

or you will be voting for special

privilege." Obviously, the Democratic

party's interests and those of his

listeners coincided perfectly. The short

speech concluded, he would ask his

audience, "Do you want to meet my

family?" and amid a chorus of

cheers, Mrs. Truman and Margaret would

step onto the front of the platform to

smile and wave their greetings to the

assembled Ohioans. Then, with the local

high school band blaring, the

train would pull away slowly, the

nation's first family smiling and waving

goodbye.38

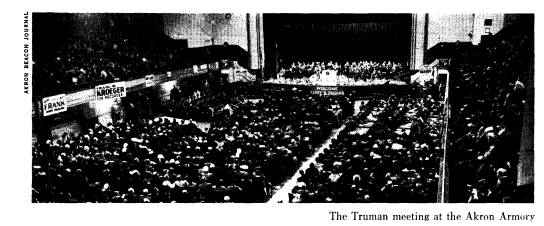

At Akron, where Truman had already

promised to "take the hide off the

Republicans,"39 a very

large and enthusiastic throng, estimated to be near

three hundred thousand in number,

welcomed the president into the Rubber

City as "the rubber workers and the

Democratic machine put on the biggest

political show in the city's

history."40 Still fresh despite the long day of

traveling, hand-shaking, and speaking,

Truman made a strong bid for the

state's labor vote in his 9 P.M.

state-wide radio speech from the Akron

Armory.41 Those who had hoped

for a Truman-type speech were not dis-

appointed, for in an extremely partisan

address he criticized the Republican

congressional leadership for the

Taft-Hartley act and, in doing so, blandly

assumed that all Republicans were

anti-labor. He reminded the armory

audience of twenty-five hundred, and

untold numbers listening on the radio,

that the Republicans had vowed to kill

the gains made by labor during the

New Deal. Fully embracing the New Deal,

Truman said: "The Republicans

don't like the New Deal. They never

liked the New Deal, and they would

like to get rid of it." They were

"waiting eagerly for the time when they

|

|

|

can go ahead and do a real hatchet job on the New Deal without inter- ference," he warned.42 Thus, on a plane of high partisanship, Harry S. Truman ended a fifteen- hour campaign during which he made his major appeal to the Ohio elector- ate. By eight o'clock the following morning he had retraced his trail across northern Ohio and was entering Indiana to begin an equally extensive cam- paign in Hoosierland. What effect did this whirlwind whistle-stop trip have upon the Ohio electorate? Although he was greeted by large crowds throughout the state (except for his early morning visit in traditionally Republican Cincinnati), Truman was probably seen by little more than a half-million persons; and a large number of these were school children. He did not say anything in his speeches that he did not utter time and again in other states. He did not visit many of the major Ohio cities; in fact, he spent valuable time in small towns. However, the psychological impact of the president taking the time to stump representative sections of Ohio asking for support cannot be under- estimated. This is especially significant in view of the fact that Dewey did not actively campaign in the state, for he apparently accepted the opinion of the "experts" that the state was all wrapped up in a Republican gunny sack. Because of the very large shift in the farm vote in Ohio, the time spent in the rural areas seems not to have been wasted. The short visits to representative small rural communities added an important dimension to the Ohio whistle-stop campaign At the end of the day, Frank Lausche, destined to sweep to an easy 215,000-vote victory in his quest to regain the governorship, wholeheartedly endorsed the Truman candidacy in a near-poetic statement which came as a surprise to many Ohio politicians. "Harry Truman," Lausche said, "possesses a soul that reflects the soul of America. He is a good man, a fearless man. He has tried to conduct the affairs of this country so as to bring the greatest good to the greatest number. I will cast my ballot for him in the belief that the nation will be secure by his guidance."43 This ringing endorsement certainly did Truman's cause no harm and possibly |

WHISTLE-STOPPING THROUGH OHIO 123

helped attract independent voters,

among whom Lausche was strong. What

greatly impressed Lausche was the

surprisingly large crowds. "At every

village, town and city, the crowds

waited in startling numbers," one national

magazine reported.44 At one

city the amazed Lausche is reported to have

told Truman, "This is the biggest

crowd I ever saw in Ohio."45

Despite the emphasis upon the issues of

labor, housing, and inflation,

the election returns indicated a slight

loss from the 1944 level in the vote

of labor. It was the radical switch in

the Ohio farm vote which returned

Ohio to the Democratic column. While he

lost slightly in such industrial

areas as Akron and Dayton,46 Truman

made huge gains in the rural areas.

In Putnam County, for example, where

Truman spent ten minutes at Ottawa

discussing the gains made by the farmer

under Democratic rule, the vote

changed from 71.8 percent for Dewey in

1944 to 50.5 percent for Truman.

In Allen County, where he stopped at

Lima, Truman cut the 1944 Dewey

margin by more than fifty percent; the

county went from a 21,024 to a 12,564

popular vote Republican romp in 1944,

to a much closer 17,380 to 13,161

Dewey victory. In Shelby County, where

he visited Sidney, which in 1944

had voted for Dewey by about 1,500

votes (7,084 to 5,622), Truman re-

versed the margin (6,939 to 5,406).47

In the industrial areas, such as

Hamilton, Dayton, and Akron, while the

Democratic margin fell slightly

from 1944, the margin of victory was

still substantial. In these areas his

aim undoubtedly was merely to maintain

his party's strength, and in large

measure he was successful. However, as

the vote returns show, the foray

into the rural areas certainly did not

hurt the Truman cause.

While it is impossible to establish

completely the efficacy of such a cam-

paign trip, the evidence does clearly

suggest that the whistle-stop visit by

Truman to Ohio was an important factor

in determining the final outcome.

Mr. Truman maintains that this trip was

"most decisive," although he is

quick to point out, "I knew I

would win all the time."48 Whatever the

actual effect, the nation-wide Truman

whistle-stop campaign, which covered

22,000 miles and entailed 351 prepared

speeches within a six-weeks period,

is an important event in American

political history. Recalling with obvious

pleasure the Ohio phase of this

campaign, Truman notes that it proved to be

"a grand time" for him as he

presented "the facts as I saw them" to the

hundreds of thousands who heard him on

a cool, windy, sometimes rainy

October Monday in 1948.49

THE AUTHOR: Richard O. Davies is a

graduate student and part-time

instructor in

American history at the University of

Mis-

souri. A native of Ohio, he holds

degrees

from Marietta College and Ohio

University.