Ohio History Journal

VIRGINIA E. AND ROBERT W. MCCORMICK

Agricultural Trains: An Innovative

Educational Partnership Between

Universities and Railroads

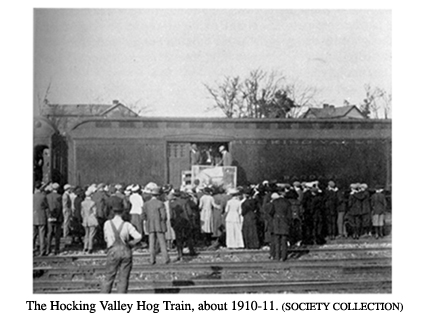

The handbill said 1:10 P.M., Thursday,

October 26, 19111 but by

one o'clock a crowd had collected and

was greeting each farm wagon

or buggy as neighbors arrived. A

stranger might have described the

gathering as festive; not the exuberance

of a 4th of July celebration,

but an expectant air akin to a farm

auction or the county fair. Beside

the Hocking Valley Railroad Depot the

mood reflected a break from

the work of harvest, the sociability of

friends and neighbors, and

the anticipation of a program to be seen

and heard. Men stood by

their horses and women held the hands of

small children as the

steam whistle announced the approach of

the special train. By the

time the engine and three coaches

settled to a halt at the Logan,

Ohio, station, the crowd was moving

toward the baggage car where a

platform was being cranked down to

present the first star of the day:

a prize Poland China hog!

For the next hour and a half people

flowed into the coaches to

hear Professor Johnson of the Ohio State

University lecture on soil

improvement or C.R. Titlow of the

agricultural extension department

show stereopticon views of improvements

for country life.2 But many

of the farmers had come especially to

see the stars in the baggage

car: the Berkshire, Yorkshire, Poland

China and Duroc Jersey hogs

selected by the agricultural college to

exemplify the well-bred ani-

mals of scientific hog culture.

The crowd attending the Hocking Valley

"Hog Special" did not

Virginia E. McCormick has served on the

faculties of Pennsylvania State University,

Iowa State University, and The Ohio

State University, and Robert W. McCormick is an

Ohio State University Emeritus Professor

of Agricultural Education. A portion of this

article appeared in their recent book, A.

B. Graham: Country Schoolmaster and Exten-

sion Pioneer.

1. Hocking Valley Railroad Handbill,

"Hog Special" October 23-27, 1911.

2. "Agricultural Extension," Lancaster

Daily Eagle, October. 26, 1911.

|

Agricultural Trains 35 |

|

|

|

realize that they were participants at the zenith of an unusual educa- tional venture. The Ohio Farmer would soon be noting proudly that from January 1, 1911, to January 1, 1912, fourteen special agricultural trains under the jurisdiction of the Ohio State University College of Agriculture had operated for fifty days, traveling 3,379 miles, making 360 stops in 68 counties, with 42,198 persons attending their lectures.3 Ohio was an excellent example of a national movement which peaked that year with seventy-one trains in twenty-eight states attracting some 995,220 people.4 It was a phenomenon which flourished across much of rural Amer- ica during the decade from 1904 through 1914, and it was an early and exotic example of education taken from institutions of higher ed- ucation directly to the adults of the community. In October 1911 the Ohio State lecturers and the Hocking Valley rail agents had no more suspicion than the crowds flocking through their cars that factors similar to those which had created this unique partnership between land-grant universities and railroad companies a few years earlier

3. "Agricultural Trains in Ohio," Ohio Farmer, 129 (March 2, 1912)14-294. 4. Alfred C. True, A History of Agricultural Extension Work in the United States, 1785-1923 (Washington, D.C., 1928), 30. |

36 OHIO HISTORY

were about to cause its demise. The

strengths and weaknesses of this

early partnership between public

universities and private business of-

fer thought-provoking insights for

contemporary educators attempt-

ing to forge linkages between

educational institutions and the busi-

ness community.

At the turn of the twentieth century the

agricultural industry was a

dominant factor in the national economy,

and railroads had become

the principal means for transporting its

goods. Ohio's diversified cli-

mate and soils combined with its

geographic position between east

and west to present a microcosm of

national trends regarding agricul-

tural production and marketing. In 1899,

ninety-five incorporated rail-

road companies were operating in the

state, seventy of them entirely

within its borders, over 8,767 miles of

main line track.5 Company offi-

cials boasted of passenger service every

half-hour in densely popu-

lated districts and engines capable of

producing speeds approaching

a mile a minute. Rail technology was

firmly in position, and transpor-

tation companies were competing

aggressively for the freight tonnage

which produced their greatest profits.

At the same time Ohio farmers, like

their counterparts across the

nation, were eagerly seeking information

which would allow them

to increase their production and

profits. Ohio had long held local

Farmers' Institutes under the auspices

of the State Board of Agricul-

ture, and Columbus had just hosted the

national meeting for the or-

ganizers and lecturers of such meetings.6

But more significantly, the

Hatch Act of 1887 had provided each

state with federal funds to es-

tablish an agricultural experiment

station.7 In 1895, a nucleus of alum-

ni from the College of Agriculture at

Ohio State University organized

an Agricultural Students Union to

conduct local experiments in co-

operation with Ohio's agricultural

research station. They generated

awareness of scientific agricultural

practices statewide and succeeded

in pressuring university trustees to

establish an agricultural extension

service within the college of

agriculture to disseminate agricultural re-

search. When A.B. Graham became its

first superintendent July 1,

5. R.S. Kaylor, "Ohio

Railroads," Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society

Publications, 9

(1900), 189-92.

6. John Hamilton, Farmers' Institutes

and Agricultural Extension Work in the Unit-

ed States (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Experiment Station Bul-

letin, No. 83, 1914).

7. A concise statement regarding this

legislation may be found in Roy V. Scott, The

Reluctant Farmer: The Rise of

Agricultural Extension to 1914 (Urbana,

Illinois, 1970),

33. Readers wishing more detail are

referred to Alfred C. True, A History of Agricultur-

al Experimentation and Research in

the United States, 1607-1925 (Washington,

D.C.,

1937).

Agricultural Trains 37

1905, the stage was set for launching

several aggressive methods for

extending agricultural education to

farmers.8

One of these methods adopted an

innovative idea utilized a year

earlier in Iowa. Perry G. Holden of Iowa

State College, in partnership

with the Rock Island and then with the

Burlington Railroad, ran

"Seed Corn Specials" in April

1904 to reach farmers with scientific

information just before planting season.9

Railroads had been cooper-

ating with agriculturists in several

states and in Canada for some time,

providing free passes for speakers and

transporting demonstration

equipment for Farmers' Institutes, but

Iowa's use of rail cars as mo-

bile classrooms was an instant success.

Thousands of farmers were

contacted within days, and other

railroads quickly realized that

such specials not only publicized their

line as the farmer's friend, but

by helping farmers increase their

capacity, they potentially increased

their own freight volume and net

profits. Modifications of the idea

spread rapidly to several states.

Educators realized the profit motive

behind the altruism of the

transportation companies from the

beginning, but it was a partnership

which offered mutual benefit. As one

phrased it: "In order that a

railway company may profit to the

fullest extent from the agriculture

contiguous to its lines, it has now

become clear that it must do more

than construct tracks, run trains, and

carry freight. It must come in a

helpful way into direct personal contact

with the farmers. The policy

of standing aloof and regarding country

people as aliens is disastrous.

The average farmer is not a merchant; he

is a producer, and conse-

quently must have assistance in selling

if he is to realize the greatest

possible profit for his labor."10

No one denied that the exotic nature of

the method was a signifi-

cant factor in its educational

attraction. When the U.S. Department of

Agriculture sent its farmers' institute

specialist out in the spring of

1906 to participate on the Illinois

Central Railroad agricultural special,

he reported: "Although the country

roads were deep with mud, the

attendance at the stations at which the

stops were made was all that

could have been desired, ranging in

number from 150 to 400. The

8. V.E. & R.W. McCormick, A.B.

Graham: Country Schoolmaster and Extension Pi-

oneer (Worthington, Ohio, 1984), 104-05; Carlton F.

Christian, History of Cooperative

Extension Work in Agriculture and

Home Economics in Ohio (Columbus,

Ohio, 1959),

2.

9. Scott, Reluctant Farmer, 178-79.

10. John Hamilton, The Transportation

Companies as Factors in Agricultural Exten-

sion, U.S.D.A., Office of Experiment Stations, Circular 112

(Washington, D.C.: Gov-

ernment Printing Office, 1911), 12.

|

38 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

novelty of the method has no doubt had something to do with the attendance, but there seems also to have been, as evidenced by the close attention given to the lectures and by the questions asked, a real desire for information."11 It was in this climate that Ohio launched its first agricultural train the last week of December 1906, a cooperative venture arranged by Dean Homer C. Price of the Ohio State University College of Agricul- ture with the agents of the Cincinnati district of the "Big Four."12 Beginning at Germantown in Montgomery County and concluding at West Unity in Williams County, this first train traveled 145 miles across some of Ohio's richest farmland, making seventeen stops of ap- proximately forty-five minutes each during its two-day journey. Two cars featured simultaneous lectures on corn and alfalfa and the speak-

11. Alfred C. True, A History of Agricultural Extension Work in the United States, 1785-1923, 29. 12. Christian, Cooperative Extension in Ohio, 5; The "Big Four" was the Cincinnati, Cleveland, Chicago, and St. Louis Railroad which had consolidated several earlier smaller lines. |

|

Agricultural Trains 39 |

|

|

|

ers coordinated by Dean Price and Director Thorne of the Agricul- tural Experiment Station included Professors Ford and McCall of the O.S.U. agronomy faculty, the president of the Grain Dealers' Associ- ation, the chief grain inspector of the Toledo Produce Exchange, and the secretary of the Ohio Millers' Association.13 All participants ex- pected benefits. Farmers expected expert advice for improving pro- duction and profits, railroads and grain dealers expected to increase profits by handling larger grain tonnage, and the college expected in- creased funding for research and instruction. The agricultural college magazine boasted that, "Over 2300 farmers were addressed on the trip and every one connected with the train was enthusiastic over its success. The audience were attentive and anxious to hear every word the speakers had to say and the only regret that was heard was the fact that the train could not stop longer."14 While the college might be accused of exaggerating its success slightly, there is no doubt that other railroad lines were immediately offering to sponsor such trains. In April 1907 Ohio's second train ran

13. "Agricultural Car Gives Advice," Mercer County Observer, January 3, 1907. 14. "Agricultural Special Train," The Agricultural Student, XIII, (February, 1907), 4-6. |

40 OHIO HISTORY

for a week, with two days on B. & O.

lines from Columbus to Blan-

chester to Chillicothe and three days on

the Pennsylvania Railroad

across western Ohio. Evening meetings

were added at the overnight

stops in Blanchester, Xenia and Piqua to

increase the educational im-

pact. These special agricultural trains

were added to the responsibili-

ties of the fledgling agricultural

extension department which was op-

erating on a budget derived from the

"produce fund" generated by

product sales from the university farm.

The department was still

more than two years away from state

support and almost six years re-

moved from its first federal funding.

But the college was already well

aware these trains were generating good

will as well as teaching better

farming methods. Its staff writer stated

confidently, "Without doubt

a good many people have been given a

closer acquaintance with the

Agricultural College and Experiment

Station, and the seed thus sown

will in time bear fruit."15

Both geography and the seasons dictated

that agricultural trains

be specialized for specific audiences.

While soil improvement lec-

tures might be relevant to all, many who

wished recommendations

regarding fruit tree spraying and

pruning had little interest in scientif-

ic poultry or swine culture, and seed

wheat varieties generated far

more interest in the fall, and seed corn

in the early spring. Such spe-

cialization suited the agricultural

college and experiment station be-

cause the railroads wanted to reach as

many people as possible with

stops of an hour or less. This allowed

time only for exhibits and a

very quick message, and the college

could not afford to staff trains

with several faculty members speaking

briefly. Special topics also

suited the transportation companies who

could have the distinction

of an agricultural train which differed

from their competitors, or a

train which had run over their lines a

year or two earlier. Ohio's di-

versified agriculture provided audiences

for specials in dairy, poultry,

horticulture, and swine as well as

general agricultural exhibits re-

ferred to by some lecturers as the

"circus car."

But the goals of educators and

transportation companies frequently

required compromises. Railroads

preferred trains which contacted

the largest number of people in the

shortest period of time by em-

phasizing only exhibits at frequent

stops as short as a half-hour. Uni-

versity professors preferred several

hours for lectures, demonstra-

tions and discussion. Ohio evolved a

compromise which usually

scheduled ninety-minute stops, allowing

participants a half-hour

15. "Second Agricultural

Special," The Agricultural Student, XIII, (May, 1907), 5.

Agricultural Trains 41

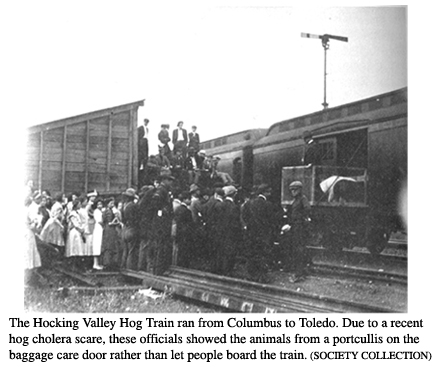

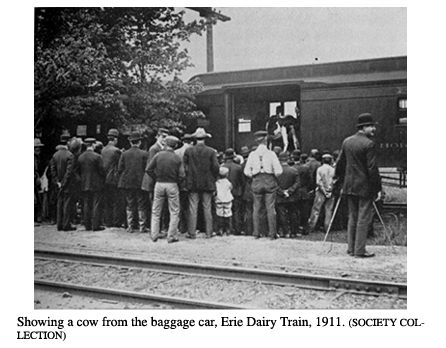

each for a general lecture on crops or

soils, a special topic lecture, and

a view of exhibits.16 But

the size of the crowds often caused sched-

ule delays, and space was rarely

adequate. The audience frequently

viewed prize livestock from a baggage

car or station platform, and

photographs from the Erie Railroad's

"Dairy Special" clearly show

that on a rainy day the cow had the

covered platform and the audi-

ence held the umbrellas!

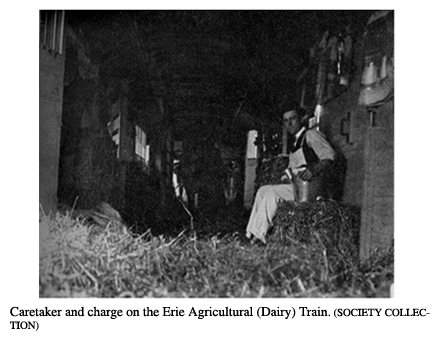

This 1910 "Dairy Special" was

Ohio's first train to carry livestock.

Three dairymen were invited to bring one

of their purebred Jersey,

Guernsey, and Holstein cows and describe

their breed's advantages

compared to the "dual purpose scrub

cow" brought along for com-

parison. Professor Erf of the

university's dairy science department

coordinated a teaching staff which

included Professor Neale lectur-

ing on animal nutrition, a

representative from the U.S. Department of

Agriculture speaking on sanitation, and

the president of the Ohio Dai-

ryman's Association as well as the three

dairymen with their prize

stock. It was an early example of what

would later become a Coopera-

tive Extension Service trademark: the

involvement of local persons

and organizations in program planning,

funding, teaching and evalua-

tion. News reporters were as impressed

as farmers, with one describ-

ing the Guernsey breeder's description

of feeding and testing in

cooperation with the Agricultural Experiment

Station as abounding in

"many practical hints drawn from

his own extended observation and

experience." 17

The college concluded that an average of

200 persons per stop

"shows the growing interest in this

branch of agriculture and the ap-

preciation of the farmers of the state

in the opportunity given them to

receive a dairy education at their very

doors."18 Agricultural exten-

sion was constantly seeking

opportunities to ensure that the enthusi-

asm generated by agricultural trains

would be translated to other ed-

ucational efforts. When the dairy train

stopped in Warren, Ohio,

overnight, superintendent Graham invited

the mayor to close the

evening meeting and the newspaper quoted

him expressing the

"hope and belief that Warren

citizens would make an effort to get to

the agricultural extension school which

will be held somewhere in

the county early next year."19

16. "Agricultural Trains,"

A.B. Graham manuscript collection, The Ohio State Uni-

versity Archives, Record Group 40/8, Box

2, Folder 46.

17. "Dairying Discussed at City

Hall," Western Reserve Democrat, May 26, 1910.

18. "Dairy Special in Northeastern

Ohio," The Agricultural Student, XVI, (June,

1910), 23.

19. Western Reserve Democrat, May

26, 1910.

42 OHIO HISTORY

Extension educators had quickly realized

that agricultural trains

were most effective in creating

awareness of a need and generating in-

terest for more information. C.R.

Titlow, who organized the Ohio

trains for several years before going to

West Virginia as agricultural ex-

tension director, expressed this clearly

in a paper prepared for the

1912 conference of land-grant college

educators. "Farmers living in

sections traversed by agricultural

trains, as compared with those not

thus served, are more apt to request

extension work, pruning and

spraying demonstrations, etc. We can

almost trace the routes of this

year's special trains by noting the

locations of our pruning and spray-

ing demonstrations."20

Educators were as aware as the rail

agents of the advertising value

of these trains. Handbills and newspaper

advertisements alerted

communities to planned specials in a

style not unlike current "ad-

vance teams" for political

campaigns. Little was left to chance or local

reporters. As Superintendent Graham

explained, "Our news man and

his portable typewriter occupied an

important place in the baggage

car; he had a local story for every stop

having a newspaper."21 Edu-

cational bulletins were distributed

freely. "No one should leave the

train without something in his hands to

carry home. The train is an

exponent, an advertiser, if you please,

of the agricultural college.

Many students come to college saying

that they heard this man or

that on the agricultural train, were

attracted by him and so decided

to enter college."22

College reports cited examples to show

that agricultural trains were

accomplishing the increased productivity

which was their goal. One

farmer living near Charleston, West

Virginia, claimed that he in-

creased his income from 1 1/2 acres from

$47 to $1204.65 simply be-

cause he attended a special truck

gardening train. A Barnesville,

Ohio, farmer reported clearing $700 from

a 1 3/4 acre orchard by fol-

lowing the instructions given in an

agricultural train lecture on pruning

and spraying.23 But educators

were soon aware that these were ex-

20. C.R. Titlow, "Special Trains as

a Means of Extension Teaching," paper presented

November 14, 1912, Proceedings of the

26th Annual Convention of the Association of

American Agricultural Colleges and

Experiment Stations (Burlington, Vt.,

1913) 215-17.

21. A.B. Graham, "Agricultural

Extension in its Infancy in Ohio," speech to Agri-

cultural Education 526, Autumn Quarter,

1955; O.S.U. Archives, Record Group 40/8,

Box 3, Folder 15.

22. A.B. Graham, statement made in round

table discussion following Titlow's pres-

entation noted above in A.A.A.C.E.S.

Proceedings, 220.

23. Titlow, A.A.A.C.E.S. Proceedings,

216.

|

Agricultural Trains 43 |

|

|

|

ceptions, and most participants needed follow-up demonstrations which the trains could not provide. Ohio attempted to compromise by scheduling evening lectures in county seat towns when trains stopped for the night. It must have been a grueling schedule for the lecturers who were on the road at least a week or longer, eating and sleeping in a coach car. Local report- ers suggest that results were mixed. Describing the lecture at the Del- aware, Ohio, city hall, one noted, "In the audience were several women, showing that the interest in raising hogs is not confined to the male side of the house."24 Another began positively, "Judging from the large attendance of county people at the courthouse last Thursday night, when they were addressed by experts from the state agricultural college and the experiment station, Vinton County farmers are ready to listen to any information or advice tending to the improvement of crops and the raising of better livestock," but con- cluded honestly, "Most of those present would rather have been privileged to hear the lecture at the train and see the prize hogs."25

24. "Hog Lecture at City Hall," Delaware Daily Journal Herald, October 25, 1911. 25. "A Big Crowd," McArthur Democrat-Enquirer, November 2, 1911. |

44 OHIO HISTORY

This is dramatic evidence of the dilemma

which to this day con-

founds advertising copywriters as well

as educators. Methods must

attract attention without overpowering

the message conveyed.

Agricultural trains throughout the

country became popular so

quickly that it was 1910 before the

U.S.D.A. conducted a survey to

assess their scope, cost, and results as

perceived by the railroad

employees who organized them and the

lecturers who taught on

them.26 One hundred and three

railroads responded, and 52 re-

ported operating agricultural trains

during the year ending June 30,

1910. These special trains averaged 4.6

cars per train with stops rang-

ing from 40 minutes to 2 days. Total

costs were estimated at $91,424

and attendance at 379,290 people, but

since all companies did not re-

spond to all questions, these figures

should be viewed with caution.

From the beginning rail companies paid

all expenses for operating

agricultural trains, and the university

paid instructors' salaries. Farm

equipment and supply dealers quickly

became anxious to have their

products used or displayed, and it soon

became a source of contro-

versy when agents for everything from

fertilizer to farm papers sought

and were denied places on Ohio trains.

But the land-grant university

was publicly funded and the college of

agriculture felt a moral obliga-

tion to avoid even a semblance of

commercial endorsement.27 It was

a touchy issue, with big business at

stake. In 1910, Ohio railroads

were hauling 232,646,532 tons of freight

an average distance of 102

miles per ton at an average cost of

one-half cent per ton/mile.28 The

rail industry touched every business,

and its agents were anxious to

make friends and alienate no one. Some

transportation companies be-

gan to broaden their relationships with

farmers by establishing dem-

onstration farms along their right of

ways, promoting marketing coop-

eratives, and offering scholarships for

agricultural study.

Agricultural extension, too, was moving

beyond the awareness lev-

el. Farmers had begun to trust the

college and the experiment station

instructors as sources of information

and were relying on week-long

agricultural extension schools in county

seat towns, a format man-

dated when the Ohio legislature began

appropriating funds in 1909.

In five years, the Department of

Agricultural extension had gone from

a $5000 budget allocated from the

College of Agriculture produce

26. John Hamilton, The Transportation

Companies as Factors in Agricultural Exten-

sion.

27. Christian, Cooperative Extension

in Ohio, 6; Graham mss. O.S.U. Archives RG

40/8/2/46.

28. Annual Report, Railroad

Commission of Ohio, 1910, 477.

Agricultural Trains 45

fund to a $50,000 budget appropriated by

the state legislature.29 Like

many movements which experience a burst

of glory just before their

demise, Ohio's last agricultural trains

were extravaganzas. The State

Board of Agriculture joined the

experiment station in mounting an ex-

hibit of agricultural products, which

ran as the "Ohio Booster" on

the New York Central Lines for 100 days

beginning in January 1912.

By now Superintendent Graham was openly

questioning the cost ef-

fectiveness of agricultural trains as a

teaching method and threatened

their termination without a special

appropriation. He warned, "Since

the special train service costs the

department from sixty to seventy-

five dollars per day, we shall be unable

to accept any requests made

by the railroads unless some special

provision is made to take care of

this important feature of our

work."30

Ohio's era of agricultural trains ended

with the "Better Farming"

special of the Norfolk and Western,

March 19-27, 1913. It was a story

repeated across the country, as

agricultural extension's quest for fed-

eral funding succeeded the following

year. With the Smith-Lever Act

Congress entered into a partnership with

land-grant universities, sup-

porting state and local funding for

agricultural and home economics

extension programs, and shifting

priorities to "movable schools" and

"demonstration agents".31

Agricultural trains were an exotic example

of a public and private

partnership which forced each side to

compromise its individual

goals to serve a common need. It was

both dramatically successful

and uncomfortably constraining to both

participants. In retrospect,

however, its brief lifespan can be

credited with being a significant in-

fluence in creating mass demand for

practical adult education based

upon scientific research.

29. Annual Reports of the Board of

Trustees of the Ohio State University to the Gov-

ernor of Ohio, June 30, 1905, through June 30, 1911.

30. Agricultural Extension report, 43rd

O.S.U. Trustees Report, June 1913, 85.

31. A concise statement regarding this

legislation may be found in Scott, Reluctant

Farmer, 310-11. Readers wishing more detail should consult

Alfred C. True, A History

of Agricultural Extension Work in the

United States, 1785-1923.