Ohio History Journal

BYRON D. FRUEHLING AND ROBERT H. SMITH

Subterranean Hideaways of the

Underground Railroad

in Ohio: An

Architectural,

Archaeological and

Historical Critique

of Local Traditions

During the decade that preceded the

Civil War the underground railroad be-

came increasingly active in Ohio and

elsewhere in the north.1 Although

"underground" originally may

have had much the same figurative connotation

that it has today in expressions such as

"underground newspaper," it was al-

most inevitable that the term come to

suggest in popular imagination not so

much anti-establishment concepts and

practices as activity that took place in

tunnels and subterranean places of

concealment. Oral traditions about the un-

derground railroad frequently allude to

places of concealment allegedly con-

structed by abolitionists for the use of

fleeing slaves who were making their

way toward Canada. From the time of

Wilbur H. Siebert, whose pioneering

research involved heavy reliance upon

such information,2 to the present time,

popularizers and no few historians of

the underground railroad have tended to

accept personal reminiscences about

specially-constructed secret chambers and

escape tunnels largely at face value.

Examples of this reliance on anecdotes

recorded years later, some supplied

by participants and others by persons

who relied on hearsay, are abundant.

Among Siebert's extensive compilations

one finds the statement that Joseph

Morris of Marion County installed

partitions in both the attic and the cellar

of his home in order to provide

"secret chambers for his swarthy guests."

Siebert goes on to say, largely on the

basis of statements he found in a local

newspaper article, that

Byron D. Fruehling is a graduate student

at the University of Akron. Robert H. Smith is Fox

Professor and Chair of the Program in

Archaeology at The College of Wooster. The authors

wish to thank Larry Gara for reading an

early draft of this paper and making helpful

suggestions, as well as Dennis

Monbarren, Denise Monbarren, and Ethel M. Parker of Wooster

for their assistance in tracking down

certain items of information.

1. For general orientation and a recent,

concise bibliography, see Charles L. Blockson, The

Underground Railroad (New York, 1987).

2. Siebert's most important, and still

influential, work is The Underground Railroad from

Slavery to Freedom (New York, 1898).

Subterranean Hideaways

99

the garret was a carefully constructed

labyrinth and . . . the cellar had two secret

rooms, each capable of serving as a

secure hiding-place for a dozen refugees.

These rooms were hidden by large

cupboards fastened to their doors. From the cel-

lar two tunnels led out, one to the barn

and the other to the corn-crib. These pas-

sages were concealed in the same manner

as the secret chambers and afforded safe

egress from the house when it was

surrounded by slave-hunters. It is said that in

several instances Negroes made good

their escape while their owners were on guard

outside the house.3

Half a century later historian Ralph

Watts cited, apparently on the basis of

the recollections of an elderly Mrs.

Kent around the turn of the century, inci-

dents in the life of Udney Hyde of Brown

County, who was reputed to have

gone to great effort to construct

concealed places for fugitive slaves. Having

built a new home, he dug a basement

under the cabin that he had previously

occupied, throwing the soil into an old

well to escape suspicion; he then cov-

ered the trapdoor entrance with wheat,

"so that when anyone approached

whose mission was unwonted, some of the

family would be busily engaged

in flailing grain."4 In

addition, we are told, Hyde concealed fugitives in a

well near his livery barn. "He had

a platform placed in the well, which was

an excavation some six or seven feet in

diameter, on which the negroes could

stand during the day, waiting to be sent

farther on their trip to Canada when

darkness came."5 Watts

narrates other stories about the deceptions carried out

by this determined abolitionist, through

whose underground railroad station

eventually passed, by Hyde's count, an

astounding five hundred seventeen

fugitives.6 More recently

Burke and Bensch have passed on the tradition--as

they label it-that in Hocking County

"there was a tunnel under [Hanes']

mill through which many slaves passed to

freedom. Among residences in

Mount Pleasant which were known to have

hiding places for runaway slaves

was Quaker Hill."7 Blockson

cites traditions about the resourceful abolition-

3. Wilbur H. Siebert, "A Quaker

Section of the Underground Railroad in Northern Ohio,"

Ohio Archaeological and Historical

Publications, 39 (1930), 486-87.

4. Ralph M. Watts, "History of the

Underground Railroad in Mechanicsburg," Ohio

Archaeological and Historical

Quarterly, 43 (July, 1934), 216.

Details about concealed

entrances were, understandably, a

stock-in-trade of traditions about hiding places under floors.

An account of the method employed by

John Harvey in his home near Savannah in Ashland

County relates that Harvey, having

hidden slaves beneath the floor, replaced the floor boards

and had his wife sit atop them in a

rocking chair while slave hunters searched in vain for the

fugitives (News Journal [Mansfield,

Ohio], Sunday, May 19, 1988). Blockson in The

Underground Railroad, 249, relates an almost identical tale about

abolitionist William

Smallwood in upstate New York. Siebert

records that an abolitionist near Delaware, Ohio, hid

a female slave and her three children

under the floor of his barn, then spread harvested wheat

stalks on the floor and set his horses

to tramping out the grain to muffle any noise that the

children might make (The Underground

Railroad, 499); a similar story about an episode in

southern Indiana is narrated in William

Monroe Cockrum, History of the Underground Railroad

(Oakland City, Indiana, 1915), 71.

5. Watts, op. cit., 220.

6. Ibid., 219.

7. James L. Burke and Donald E. Bensch,

"Mount Pleasant and the Early Quakers of

100 OHIO

HISTORY

ists in Ashtabula County, one of whom

was Col. William Hubbard, who

built a tunnel for escaping slaves that

allegedly led from his barn to the shore

of Lake Erie.8

The primary emphasis in these and many

other traditions that have been

transmitted is on the clever deception

of opponents and the large numbers of

fugitives that had been assisted.

Persons who had no direct knowledge were

often eager to attribute to abolitionists'

houses a specialized function in this

romanticized picture of the underground

railroad. Indeed, with the passage of

time almost any venerable house, even if

constructed after the Civil War or

owned by a person with no known

abolitionist associations, could be included

in the mystique of the underground

railroad.

The folkloristic elements in many of the

stories are patent. Larry Gara,

who is among the few historians who have

evaluated critically the data per-

taining to the underground railroad, has

pointed in The Liberty Line to the

tendentious features that exist in some

of the oral traditions, as well as to the

inconsistencies between anecdotal

material and available statistics pertaining

to the migration of slaves. He is aware

of the tendency for anecdotes to be at-

tached to the homes of well-known

abolitionists, and argues convincingly

that far fewer abolitionists actually

gave refuge to fleeing slaves than they

later claimed. "Each local

story," he insists, "should be investigated, the ba-

sis for the tradition [be] examined, and

the sources [be] evaluated,"9 though

he gives little indication as to how

such investigation should be carried out.

Gara's own judgment, based chiefly on a

rational critique of the data rather

than field investigations, is that many

of the places that local tradition de-

clares to have been constructed for the

concealment of fugitive slaves were

simply storage places, cisterns, air

shafts or other commonplace features of

American life in the mid-19th century.10

Clearly one of the methods of evaluating

traditions about secret compart-

ments or tunnels constructed

specifically to assist fugitive slaves is on-site

Ohio," Ohio History, 83

(Autumn, 1974), 245-46.

8. Charles L. Blockson, The

Underground Railroad, 211. Blockson does not stress the

question of the historical accuracy of the accounts of

concealed chambers which he cites. In

his "Escape from Slavery: The

Underground Railroad," National Geographic Magazine, 166

(July-December, 1984), 25, a photograph

shows a sliding shelf beside the stairway in the home

of the Alexander Dobbin (now a

restaurant) in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, which slides back to

reveal a crawl-space which the caption

says is "large enough to hide several adults"--wording

that implies that the space was, in

fact, designed for that purpose and presumably was so used.

Other photographs in the article show

Joseph Goodrich's inn in Milton, Wisconsin, constructed

ca. 1835-1845, which has a tunnel in its basement that

leads to the cellar of a log cabin forty

feet distant (ibid., 22-23); the caption

states that "if any customers were slave catchers, the

fugitives resting and eating in his

basement could exit to the cabin and follow creek beds and

lakes north to Canada."

9. Larry Gara, The Liberty Line: The

Legend of the Underground Railroad (Lexington,

1961), 192.

10. Ibid., 11. See also his "The

Underground Railroad: A Re-evaluation," Ohio Historical

Quarterly, 69 (July, 1960), 218.

|

Subterranean Hideaways 101 |

102 OHIO

HISTORY

investigation. At the time Gara wrote,

scarcely any houses had been sub-

jected to architectural, much less

archaeological, investigation. In the subse-

quent decades the few investigations

that have been carried out, mostly outside

Ohio, have produced generally negative

results. A case in point is the

William Tallman House in Rock County,

Wisconsin, constructed in 1855-

1857. Although Blockson describes this

house as probably the most impor-

tant underground railroad station in

Wisconsin, "specifically built to accom-

modate the movement of fugitive

slaves,"11 Iva Herzfeldt, site manager of

the Tallman Restorations, points out

that no evidence exists that would sup-

port such an assertion, or that would

demonstrate that the house was a station

of the underground railroad.12 A

stairway ascending from a second-story

closet to the roof, claimed to have been

designed as a secret passageway for

use by fugitive slaves, appears to have

served the more prosaic function of

providing access to the gutters for

purposes of cleaning; large containers in

which the water from the roof was

collected are, in fact, still extant in the at-

tic. A tradition about an escape tunnel

from the cellar may have originated

with a drainage pipe, too small for a

person to crawl through, that runs from

the house to the Rock River.13

However desirable the examination of

actual sites may be, one cannot in-

vestigate all of the hundreds of such

claims; selectivity is required. True, ran-

dom sampling would be impractical, but

the investigation of a group of such

houses situated within a coherent,

limited geographical region is feasible.

The determination of a suitable part of

the state for investigation was carried

out primarily with the aid of Siebert's

map14 and Galbreath's list of under-

ground railroad stations.15 The

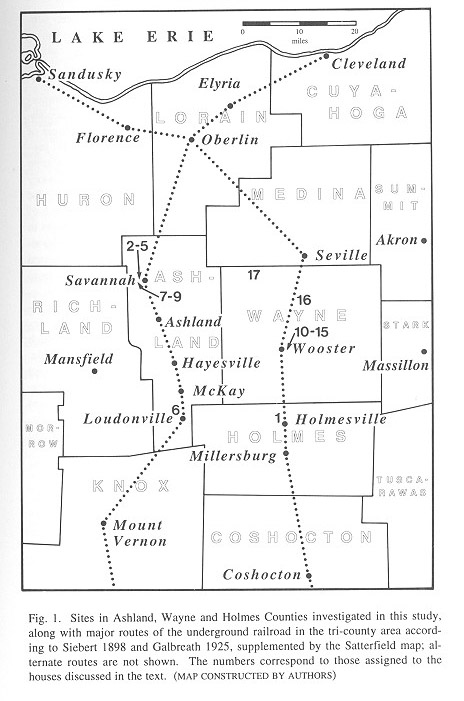

area selected comprised Ashland, Wayne and

Holmes Counties in northeastern Ohio,

through which ran two of the under-

ground railroad routes from the Ohio

River to Lake Erie (Fig. 1). One route

11. Blockson, The Underground

Railroad, 194, who describes the Tallman House as having

"hiding places in both the basement

and the attic and a special lookout on the roof.... When

fugitives approached the house, a bell

was rung to alert the servants and then a signal was

given to the fugitives from a large

stained-glass window. When the slaves saw the dim light,

they proceeded to enter the cellar door

that was always left open. The ingenious Tallman led

his charges through a secret stairway in

the maid's closet and finally through an underground

tunnel, which led to the Rock River,

where an Underground Railroad agent took them by

riverboat to Milton."

12. Telephone interview with Iva

Herzfeldt, April, 1991; see Debra Jensen-De Hart,

"Uncovering the Secret of

Slaves," Janesville Gazette, March 31, 1991. The structure of the

Tallman House was investigated when a

restoration was carried out some years ago.

13. Allegations of concealed chambers

and tunnels of the underground railroad are abun-

dant throughout the Northern states.

Sometimes undocumented claims are given credence by

leading periodicals, such as the United

Press release in the Christian Science Monitor on May

23, 1979, asserting that a city work

crew in Erie, Pennsylvania, had uncovered a brick-lined

tunnel four feet in diameter lying

twelve feet below the surface that had been used by runaway

slaves. Ken Pfirman, Archivist of the

Erie Historical Museum, notes that the tunnel proved to

be an early storm sewer (telephone

interview, August 8, 1991).

14. Siebert, The Underground

Railroad, map facing p. 113.

15. Charles B. Galbreath, History of

Ohio, vol. II (Chicago and New York, 1925), 215.

Subterranean Hideaways

103

passed through Coshocton, Millersburg,

Holmes (Holmesville), Wooster,

Seville and Oberlin, before bifurcating

to Sandusky or Cleveland. Another

ran about twenty miles farther west,

passing through Mount Vernon,

Loudonville, McKay, Hayesville, Ashland

and Savannah, then on to

Oberlin.16 Numerous houses

along these routes in the three counties have

traditions of subterranean chambers or

tunnels. Regrettably, some of the

houses have been so extensively altered

that relevant original features are not

visible, and occasionally the owner's

permission for on-site inspection could

not be secured. Even with these

limitations more than a dozen houses were

investigated, yielding significant

information.17

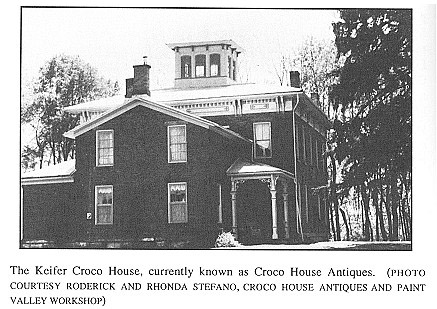

1. The Keifer Croco House

The Croco House constitutes a prime

instance of underground railroad leg-

end intertwined with history. Keifer

Croco was the descendant of an aristo-

cratic Polish family who took their

patronym after Krakow, the city from

which they migrated to the New World.18

Keifer's grandfather, Peter, came

to America as a Hessian with the British

army during the Revolutionary War,

but defected to the colonists' side. His

son, Peter Jr., settled in Holmes

County in 1813, and later served as a

district judge in Ohio.19 The house is

located on a bluff above Salt Creek,

approximately one mile northwest of

Holmesville on State Route 83.

Constructed of red brick with a sandstone

foundation, it is a nearly square

structure in Italianate style, and retains its

original widow's walk and cupola.

Investigation by the current owners places

the construction ca. 1851,20 well

within the most active period of the under-

ground railroad. The only major

alteration to the house was the addition of a

first-story kitchen in 1873.

16. The route from Loudonville to

Savannah is inferred from locations on a map in the Ruth

Satterfield Underground Railroad

Collection in The Ashland Historical Society.

The

Satterfield Collection also includes a

tabular sheet of the sites that appear on the map, as well

as color slides of those structures that

were extant in the late 1950s. See also Betty Plank,

Historical Ashland County (Ashland: The Endowment Committee of the Ashland

Historical

Society, 1987), 287.

17. Because of the very nature of oral

tradition, a complete and authoritative list of houses

having alleged places of concealment

related to the underground railroad cannot be compiled,

but the authors believe that they have

considered the major alleged sites in the tri-county area.

18. The family name is pronounced as if

it were spelled Crocko, and in fact appears with

that orthography in some old documents

and in Siebert's publications. The first name appears

in the more orthographically correct

form Kieffer in some early records.

19. Roy Stallman, "Croco

History," in Holmes County to 1985 (Salem, W. Va.: Holmes

County History Book Committee, 1985),

31; Rosanna Painter, "Old Buildings, Croco Home," in

ibid., 251.

20. Interview with owner Rod Stefano,

January, 1991.

|

104 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

Siebert includes Peter's sons, Keifer and John, in his list of those who op- erated an underground railroad station.21 Other sources provide a few anecdo- tal details. Keifer, the leader of the station, is alleged to have taken escaping slaves across the road to his brother's farmstead when he could accommodate no more persons, and the Croco brothers were said to have been involved in a skirmish with slave hunters outside Keifer's house.22 Charles Crawford, a Croco descendant, is quoted in a newspaper account as stating that the house was equipped to accommodate slaves in the attic, reached through a trapdoor in the ceiling of a second-story room, the entrance being concealed by the use of matched boards.23 That statement is, however, erroneous, for the second story proved upon examination to contain an ordinary staircase giving access to the attic, from which a ladder leads to the cupola and widow's walk. The attic was never floored. The second floor itself contains no concealed spaces, and there is no evidence of significant alterations to the second story and attic of the house since their construction. One newspaper account alludes to rumors about tunnels constructed beneath the house to facilitate the escape of slaves from bounty hunters. The pas- sages allegedly led from the basement to "caves on the estate," but subse-

21. Siebert, The Underground Railroad, 423. 22. Ed McGraw, "Runaway Slaves Found Haven," New Philadelphia-Dover Times- Reporter, Holmes County edition, ca. 1980-85; Francy Howland, "Writer Traces Slave Underground Railway in Holmes, Wayne Counties," The Daily Record (Wooster, Ohio), ca. 1950-55. 23. Howland, op. cit. |

Subterranean Hideaways 105

quently "the basement was sealed

off and the passages have now been filled

in, as have any tunnels to the

caves."24 Just how, if at all, "passages" dif-

fered from "tunnels" is not

explained. Local residents interviewed for this in-

vestigation offered a number of versions

of this tradition, variously claiming

that a tunnel led some 200 yards

northeast from Keifer Croco's house to that

of his brother, or ran a short distance

southward from the house to Salt Creek

where slaves could follow the stream

into a swamp, or even extended as far

north as another reputed underground

railroad station situated some two miles

away. One local informant stated that

when he was a boy of ten or eleven he

had entered a tunnel from the basement

of the house, but that the entrance had

subsequently been sealed up. Upon

examination, however, the stone founda-

tion of the house which forms the

basement walls proved to be both original

and solid, with no possibility that an

entryway to a tunnel ever existed.

It is clear from this evidence that even

though the Croco House may have

been a station of the underground

railroad, no architectural constructions in-

tended specifically to conceal slaves or

assist their flight were incorporated

into any part of the structure, either

at the time of its construction or subse-

quently.

2. The James Lawson House

This house is located on Townline Road

(formerly Noble Road), three

miles west of Savanah in Clearcreek

Township, which had been settled by

Scotch Presbyterians and was a center of

abolitionist sentiment. Although

James Lawson's brother John is listed by

Siebert among the abolitionists in

Ashland County, little is known about

James himself; nevertheless, an oral

tradition arose regarding the use of his

house in connection with the under-

ground railroad. Ruth Satterfield, who

in the late 1950s gathered traditions

about abolitionists and underground

railroad stations in Ashland County,

states that "a trapdoor from the

kitchen led to a dungeon in basement."25 A

chamber does exist, located, as

Satterfield notes, in the northeast corner of the

house beneath the kitchen, two of its

stone walls being those of the founda-

tion of the house.

The structure is clearly a cistern, an

installation that is by no means rare in

19th--and even early 20th-century houses

in Ohio. The interior is lined with

eight-inch-thick brick that has coats of

plaster totalling an inch in thickness.

24. Cathy Wogan, "Underground

Railroad House," The Holmes County Farmer-Hub, Oct-

ober 22, 1981, 1-2.

25. Tabular sheet in the Satterfield

Collection, which identifies each building (whether

extant or not) by the abolitionist

owner's name, the location of the building, any place of

concealment or "peculiarity"

in the structure, the ancestry of the owner, and the names of

subsequent owners, including the owner

as of February, 1960. "Dungeon" is Satterfield's

idiosyncratic term for a chamber without

doors or windows.

106 OHIO HISTORY

A hole near the top of one of the

outside walls presumably once accommo-

dated a pipe that brought rain water

from the roof. The floor has three dis-

cernable layers of plaster above a stone

or mortar base, and was found covered

with an inch or two of fine sediment,

above which lay scattered pieces of

wood and plaster debris; the outlet

drain, if any, was not evident. This cistern

retains its original trapdoor, an

opening 18 3/4 by 16 1/4 inches which had

been sealed from above when the kitchen

was later renovated but which oth-

erwise appears to be intact. Attached to

the frame is a rectangular wooden

chute 20 1/2 inches deep that may have

prevented ascending buckets from

bumping the trapdoor frame and spilling

their contents. Any inference that

this commonplace domestic installation

was constructed with the concealment

of fugitive slaves in mind is out of the

question, and there is no reason to

suppose that it was secondarily used for

such a purpose.

3. The Jane Forbes House

This house fronts Ashland County Road

686 (also known as Old County

Road 10A) some two miles northeast of

the James Lawson House. The

large, two-story white frame structure

stands on a slight rise in the fields,

one-half mile west of the Vermillion

River. The architectural style suggests

a date in the mid-19th century.

Satterfield states that the house had "a dun-

geon with a trapdoor from the

kitchen."26 Interviews with several longtime

residents in the area also brought to

light not only the familiar rumor that

there was a tunnel that led from the

house to the river, but also the tradition

that a cup tied to a string could be

sent down through the tunnel to the river

and be pulled back containing fresh

water.27

Upon investigation the house did prove

to have a doorless, windowless

chamber with exterior dimensions of

approximately 12 by 8 feet, projecting

from the north wall of the rectangular

one-room basement. The walls of the

chamber vary somewhat in thickness and,

like those of the foundation walls

of the basement, in composition. An

opening crudely cut into one of the

walls to accommodate a heating duct to

the present kitchen facilitated inspec-

tion of the interior. White plaster is

visible on all of the walls and the floor,

making the masonry smooth and

watertight. It thus immediately becomes

apparent that the chamber is nothing

more than a disused cistern analogous to

that in the Lawson House. An eight-inch

circular opening near the top of the

west wall contains the remnant of a

metal pipe, presumably one that chan-

neled water from the roof. Embedded in

the floor is a one-inch drain pipe,

toward which the floor gently slopes.

The bottom of the cistern was found

26. Tabular sheet, Satterfield

Collection.

27. Interviews with Jed Troxel, Stanley

Hissong, Dale Ramsey and Larry Bittinger in

February and March, 1991.

Subterranean Hideaways 107

covered with four inches of fine

sediment that had accumulated during the fi-

nal years of its use, on top of which

was debris from the duct installation and

a rebuilding of the floor of the chamber

above. Although the latter is now a

bathroom, it originally may have been

the kitchen, since the present kitchen

is an addition to the house. The

tradition that a cup lowered on a string could

be brought up filled with water is thus

readily explained. No evidence of a

trapdoor has survived, for the floor of

the room above the cistern has framing

that was put into place when the modern

bathroom was installed.

The tunnel that local informants

recalled as running from the basement of

the Forbes house to the Vermillion River

did not exist. Although the founda-

tion of the house is not entirely

uniform, there are neither openings nor sealed

entrances anywhere in the walls. The

house therefore has no physical features

that can be associated with the

underground railroad.

4. The Ezra Garrett House

The Garrett farmhouse is at the north

edge of Savannah, seventy-five yards

west of State Route 250. A one and

one-half story frame structure, the house

is small by comparison with the other

buildings discussed here. Despite its

modest appearance, it has been featured

frequently in histories and popular ac-

counts about the underground railroad in

northern Ohio. Siebert identifies

Garrett, who was a farmer of modest

means, as an abolitionist,28 and the

house is at the head of Satterfield's

list of Ashland County underground rail-

road stations. Garrett is credited with

transporting four to five hundred slaves

during a thirteen-year period prior to

the commencement of the Civil War.29

Published accounts30 and

local informants refer to Garrett's use of places of

concealment and escape tunnels for

fugitives. Satterfield comments about the

house with her formulaic phrase

"dungeon in basement with entrance from

room above by trapdoor," but also

adds, "tunnels to the spring in ravine and

to wagon shed." Dale Ramsey, a

local man who grew up near the Garrett

House, alleges that when he was a boy he

went down a trapdoor in the house

which gave access to a tunnel that he

followed for 200 feet in a westerly direc-

tion, and Connie Huff, a woman who was a

resident in the house in the

1940s, reports that as a youngster she

and her brother opened a trapdoor in the

floor, three feet from the northwest

corner of the main floor of the house, and

28. Siebert, The Underground

Railroad, 416.

29. Article in the News Journal (Mansfield,

Ohio), May 29, 1988. Both Emma and Martha

Garrett, Ezra's daughters, are said to

have vouched for the information given in the article

concerning their father's abolitionist

activities (William A. Duff, History of North Central Ohio

[Topeka, 1931], vol I, 180). That

Garrett assisted as many as four or five hundred slaves may,

however, be questioned.

30. Plank, Historic Ashland County, 287.

108 OHIO HISTORY

peered into a void.31 Perhaps

significantly, however, Emma Garrett's recol-

lections of the activities of her father

and other abolitionists make no mention

of either tunnels or concealed chambers.32

No trapdoor is presently visible

anywhere in the first story of the house,

where all of the flooring appears to be

original. The basement is a rectangu-

lar room with walls constructed of

large, well-trimmed stones laid with a

minimum of mortar. The ceiling is

somewhat more than six-feet high and

has large, handsawn joists, some of

which still partially retain bark. There is

only one modern and no original openings

in the walls, nor is there evidence

that any ever existed. There is,

however, a doorless, windowless space in the

basement which may have served as the

basis for Satterfield's notation about

a dungeon. Measuring 8 1/2 by 18 feet in

length, it extends along the entire

north end of the house.33 It

is separated from the rest of the basement by a

double brick wall, reported by Huff to

be intact at the time that she lived there

in the late 1940s, partly removed by the

time Satterfield made a photograph a

decade later,34 and now

largely dismantled. There is no evidence of a trapdoor

anywhere in the basement ceiling.

The compartment was filled with soil to

about half its height, with only a

crawl space left below the joists.

Because the soil might contain useful in-

formation, or even conceal the entrance

to a tunnel, two archaeological test

pits were excavated on the west side of

the enclosure, where informant

Ramsey had allegedly entered a tunnel.

No opening of any kind was encoun-

tered. Significantly, however, these

pits revealed that inside this chamber the

foundation walls become much shallower

toward the north end of the house,

and that the virgin soil had never been

excavated to the floor level of the

basement. Some occupational debris was

present in the soil above the foun-

dation level. The sounding in the

northwest corner yielded pieces of wood

which appeared to be construction

detritus, along with chunks of charred wood

(some of it wet from dampness coming

into the basement), compacted grav-

elly, grayish-brown soil containing

flecks of charcoal, and a shard of blown

glass. The other pit, dug at the

southwest corner of the chamber, produced

fragments of cattle and fowl bones,

shards from several different kinds of

household dishes, and a corroded 1845

Liberty penny.

Although it is initially tempting to see

these artifacts as evidences of hu-

man occupation, and to hypothesize that

the occupants were, as tradition

would have it, fugitive slaves, the

evidence actually points in quite a different

direction. Since this portion of the

basement was left partly unexcavated by

31. Interviews with Dale Ramsey and

Connie Huff in March, 1991.

32. See note 29.

33. If Ramsey's recollection has any

basis in fact, it may be that what he did was to traverse

the length of this narrow enclosure. To

a small boy, an eighteen-foot length of crawl space

might well later be recalled as a long

tunnel.

34. The photograph is in the Satterfield

Collection.

Subterranean Hideaways 109

the builders, it is clear that there

never was a habitable chamber here at all.

Evidently workmen had tossed both soil

and refuse, some of it from work-

men's cooking fires and meals and some

from the construction of the flooring

of the house, into this space. The brick

crosswall forming the south side of

the enclosure presumably was installed

during the construction of the house

to prevent slippage of the unexcavated

soil, as well as to block off the unex-

cavated area from the rest of the

basement. It is clear, then, that this con-

struction was not carried out for the

purpose of providing a place for conceal-

ing slaves; if such had been the case,

the space would have been made more

tolerable for occupants.

5. The Dienes House

This house, so identified by virtue of

its present ownership, is located di-

rectly between the Forbes and Garrett

Houses in Ashland County. A local

teenager alleged in interview that the

basement gives access to a tunnel

through which she had walked as a child

of about six, ca. 1978-80. The in-

formant stated that she traversed the

tunnel for about two miles until it came

to a dead end at a concrete wall.35

Upon inspection the house proved to have

a basement divided into two sections,

one of which, at the bottom of the

basement stairs, is a roughly square

room with foundation walls of field

stones; the other, linked with the first

by a doorway, is L-shaped, ending in a

modern cinderblock wall-presumably the

wall that the child saw. Because

the house stands on a small rise, no

tunnel could have extended from the

basement in any direction.

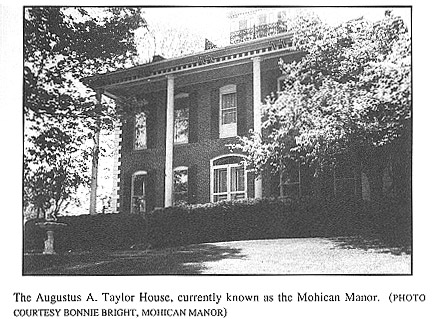

6. The Augustus A. Taylor House

Loudonville, in southern Ashland County,

is the location of the Taylor res-

idence, which at present is a restaurant

called Mohican Manor. The fine brick

structure, which perches on a hillside

at 105 North Mount Vernon Avenue,

was constructed in Italianate style in

1851,36 and is architecturally similar to

the Croco House. It was built for the

prosperous founder of several regional

mills that produced Taylor's Best Flour.37

Underground railroad documenta-

tion of this house is scarce, yet

Loudonville residents have heard about a con-

cealed basement chamber or tunnels on

the premises. One tradition avers that

a tunnel from this chamber led eastward

under the road and emerged in the

basement of a house several blocks away,

while another claims that a passage

35. Interview with the daughter of

Clarence Mosely, February, 1991.

36. Interview with owner Bonnie Bright,

March, 1991.

37. One of the mills still exists in

Loudonville under the name of the Conagra Mill.

110 OHIO HISTORY

linked the residence with its large

carriage house (still extant at the rear of the

property, though not of the same age as

the house).38

The basement of the residence contains a

walled-off space 41 feet 2 inches

long by 4 feet 8 inches wide (interior

measurements) extending across the en-

tire north end. The wall that sets this

"chamber" apart from the rest of the

basement is a massive 21 inches thick,

and was constructed in the same style

of masonry as the foundation walls; it

bonds with the east and west walls, and

thus it is unquestionably a part of the

house as originally built. Although all

of the interior faces of the walls of

the basement room are dressed and plas-

tered, those of the walls that enclose

the narrow compartment consist of un-

hewn field and river stones laid with

minimal mortar and unplastered. A 23

by 14 inch decorative iron ventilation

grill is located near the center of the

separation wall just below the joists,

and affords access from the basement

room. The north foundation wall of the

house has two blocked-up decorative

iron grills just below the joists, which

at one time provided outside ventila-

tion. Two heating ducts, additions that

probably were made when the house

was renovated in the last quarter of the

nineteenth century,39 begin at the fur-

nace in the basement room, cross the

compartment just below the joists, and

turn upward through the floor into the

parlors above.

As in the Garrett House, the soil level

in this space is high, leaving a fairly

uniform crawl space of about three feet.

The uppermost soil layer proved

upon examination to be extremely rubbly,

containing many stones resem-

bling those in the walls, though

generally smaller. On the surface, directly

below the ducts, were remnants of sawn

and hacked wood, representing con-

struction debris from the cutting of the

flooring during installation of the

ducts. Several objects lay near the

midpoint of the long enclosure, not far

from the access grill: a tobacco pouch,

a button of porcelain and metal, a pair

of trousers with a burlap rope belt

lying beside them, and a deteriorated leather

shoe sole. A foot away from this

assortment, but six inches below the sur-

face, a well-preserved 1857 Flying Eagle

penny was reportedly discovered by

one of the owners using a metal

detector.

The trousers proved to be the most

informative of these artifacts. They

were of sturdy cotton cloth,

machine-made but handsewn, much worn and of-

ten repaired. The original stitching

around the buttonholes of the fly was neat

and fine, the repairs much more

haphazard. Both knees had unrepaired tears.

Small clumps of mortar or plaster clung

to the pants in two places. The pos-

sibility that the trousers might have

been deposited relatively recently by an

Amish workman, of whom there are many in

the vicinity, could be excluded

38. Not surprisingly, the legend of

treasure has also been linked with the house. A former

owner's family, it is said, hacked holes

in the walls in their search for hidden gold.

39. The ornate iron floor grill in the

parlor above the duct is in a style contemporary with

the renovations made to the house prior

to 1900, which included the installation of new door

surrounds and stone mantles in the two

front parlors.

|

Subterranean Hideaways 111 |

|

|

|

at the outset by the presence of buttons and a metal clasp at the back of the waist, both of which are proscribed by Amish custom. Ellice Ronsheim, cu- rator of textiles at the Ohio Historical Society, examined the trousers and reported that they are work pants dating from 1850-1890.40 There is nothing about the other objects that would prevent them from being regarded as contemporary with the trousers. Although these artifacts might suggest some kind of temporary occupation of this space, and the worn state of the clothing further brings to mind indi- gent fugitive slaves, a less romantic explanation is more plausible. While the nature of the artifacts does not preclude a pre-Civil War date, any escaping slave who occupied the space for more than a very brief time would surely have removed some of the sharp stones and reshaped the soil of the crawl space into a more comfortable configuration for sitting and sleeping. The simplest explanation is that the trousers were discarded by a workman at the time of the installation of the furnace ducts. The other objects also probably were left either by the same workman or by others working on the project, who found the crawl space a convenient place for discards. The evidence, however, does not categorically exclude the possibility of a date of deposition contemporary with the construction of the house. A controlled excavation made at the southwestern corner of this area of the basement revealed that the foundation becomes much shallower at the west

40. Letter and telephone conversation with Ellice Ronsheim, March, 1991. |

112 OHIO HISTORY

end of the building, and that beneath a

layer of construction debris and rocky

earth lies virgin soil, much higher than

the floor level of the basement. The

foundation construction thus proved to

be virtually identical with that found

at the north end of the Garrett House.41

It can be seen that this crawl space

was never a habitable chamber at all,

much less one specifically designed to

accommodate slaves being transported via

the underground railroad. The

builder intended from the outset that a

portion of the space beneath the house,

where the foundation was built more

shallowly, remain unexcavated, and this

he isolated from the rest of the

basement at the time of construction.

Backfilling of above the virgin soil

during construction of the house probably

accounts for the presence of the Flying

Eagle penny-if indeed the house was

not constructed prior to 1857.

Once again, the examination of the

actual premises has not supported the

tradition that fugitive slaves were

given refuge in a specially-constructed

basement chamber. The lack of convincing

evidence tends to be corroborated

by the fact that Augustus Taylor does

not appear in Siebert's list of abolition-

ists,42 nor apparently in any

other early source.

7. The John Bebout House

This house, on Crum Road three miles

west of Savannah in Ashland

County, is alleged by Satterfield to

have had a "dungeon" measuring 15 x 18

feet, complete with a trap door.43 The

house burned about 1970. A former

resident who was interviewed stated that

the space was located beneath the

floor of the kitchen and back room and

was approximately three to five feet

high.44 The descriptions

collectively suggest that the chamber was either a

disused cistern like those in the Forbes

and Lawson Houses or a narrow foun-

dational compartment similar to the ones

in Garrett and Taylor Houses.

8. The Andrew Paxton House

This house, still standing a half-mile

southeast of Savannah on County

Road 191 in Ashland County, is said by

Satterfield to have had "a dungeon

room and tunnels leading to a ravine

west of [the] house."45 The current

41. Manifestly inaccurate, therefore, is

a drawing depicting this space in the Taylor House

as a floored chamber outfitted with

benches for the comfort of fugitive slaves, which historian-

artist Jim Baker presented in his

syndicated feature "As You Were" in Ohio newspapers on

February 2, 1979.

42. Siebert, The Underground

Railroad, 416.

43. Tabular sheet, Satterfield

Collection.

44. Interview with Robert Eby, February,

1991.

45. Tabular sheet, Satterfield

Collection.

Subterranean Hideaways 113

owner reported that the basement has a

separate area that is a crawl space,

which was closed off during remodelling.46

His description suggests that this

basement construction also was similar

to that of the Garrett and Taylor

Houses.

9. The Isaac Buchanan House

This early log house on State Route 545

at the first crossing southwest of

Savannah in Ashland County no longer

exists, but the current owner of the

property reaffirmed the story that the

cabin had served as an underground rail-

road station, as had a later house that

still stands to the east. Tradition places

a tunnel under the latter building.47

Visual inspection in a crawl space under

a modern addition to the latter building

revealed some small, unremarkable

construction anomalies, but nothing

suggesting a tunnel; an archaeological

excavation, impractical under present

circumstances, would be required in or-

der for the claim of a tunnel to be

investigated, but the prospects are not

promising.

10. The "Mayor's House"

This structure, named for its best-known

resident, William L. Long, Mayor

of Wooster during 1934-1939, is located

at 658 Pittsburgh Avenue in

Wooster (Wayne County). It is one

of several houses clustered in an old

area of the city where underground

railroad traditions have long existed.

Folklore attaches several claims to this

house, one of which is that a tunnel

led from the basement to the track of

the Pennsylvania Railroad, located only

75 feet to the north, so that fugitive

slaves could stow away on passing

trains. A more extravagant claim is that

a tunnel led from the house to the

Ohio Agricultural Research and

Development Center, situated three miles

away with an intervening valley, stream

and hills. Examination of county

maps revealed that this house was

constructed near the end of the 19th cen-

tury, as for that matter was the first

building of OARDC.

11. The Pittsburgh Avenue School

This old school in Wooster has been

razed, but a long-time employee

claims to have entered a basement tunnel

while the building yet stood, where

46. Interview with Warren Jordan,

February, 1991.

47. Interview with Clarence Mosley,

February, 1991. The log cabin is listed on the

Satterfield tabular sheet.

114 OHIO HISTORY

she saw what appeared to be makeshift

benches or beds dug into the walls of

the passageway. Although she did not

claim to have walked the length of

the tunnel, the informant stated that

the passage continued in a westerly direc-

tion toward the Jeffries House (no. 12).

One of two persons whom the in-

formant alleged could verify her

statement had, however, no recollection of

any tunnel, much less of having entered

one. If there was a tunnel of any

sort, it was not connected with the

underground railroad, since the building

was constructed in 1902.

12. The Jeffries and Pardee Houses

The Jeffries House, at 745 Pittsburgh

Avenue in Wooster, was built in

1843 by Judge John P. Jeffries, and has

long been rumored to have been an

underground railroad station with a

tunnel leading to another house, but Lola

Jeffries, daughter of Judge Jeffries,

emphatically stated in 1952 that her father

had nothing to do with the underground

railroad and that there was no tunnel

in the house.48 Interwoven in

local tradition with the Jeffries House was the

nearby Eugene Pardee House, a large

structure no longer extant that was situ-

ated about 100 feet north of Pittsburgh

Avenue, which was the home of a

19th-century Wooster attorney and strong

abolitionist.49 A red-brick barn or

carriage house associated with the

Pardee mansion still stands at 124 Massaro

Street, converted into a two-story

single-family dwelling. Local rumor al-

leges not only that the basement of this

structure was an underground railroad

station but also that Harriet Tubman

found refuge there. Some persons

whose property adjoins the converted

barn mention the existence of unex-

plained depressions in their lawns, as

if caused by a collapsed tunnel, and one

inhabitant reported that a clothesline

pole once abruptly sank into the ground.

Such cavities are not, however, unusual

in old urban areas and may represent

any number of phenomena having nothing

to do with escape tunnels.

Inspection of the basement revealed no

evidence of a tunnel or any sealed

openings in the walls.

13. The Watters House

This house, situated at 714 Pittsburgh

Avenue in Wooster, was alleged to

have contained two tunnels, one linking

the basement with that in another

48. E. H. Hauenstein, "Underground

Depots in Wayne Help Free Slaves," The Wooster

Daily Record, February 9, 1952.

49. Ibid. Pardee is perhaps identical

with the "Perdu" (no first name given) who appears in

Siebert's list of underground railroad

operators in Wayne County (The Underground Railroad,

430).

Subterranean Hideaways 115

house of the same street, and the other

extending toward the Pennsylvania

Railroad tracks. Listed among the

"Pioneer Homes" of the city and perhaps

constructed prior to 1860, the structure

no longer exists.

14. The "Ohio House"

This house, a former stagecoach tavern

located at Madison Avenue and

Spruce Street in Wooster, was alleged at

an early date as an underground rail-

road station. There is no documented

evidence of any tunnels or hidden

chambers in the building, which was

razed in the 1940s.

15. The John H. Kauke House

This now-razed residential building,

which stood on the northeast corner of

the intersection of Bowman Street and

Beall Avenue in Wooster, is rumored

to have had shackles in the basement to

keep slaves from wandering around

the town during daylight while waiting

to move to the next underground rail-

road station. The absurdity of the idea

that operators of stations would

shackle those whom they were helping to

liberate is patent. No secret rooms

or tunnels are documented. Historical

research has shown that the building

was, in fact, constructed after the

Civil War.

16. The Creston Antique House

This residence on State Route 3 at the

south edge Creston, Wayne County,

which has been used in recent years as

an antiques shop, is an alleged under-

ground railroad station. A former owner

of the shop stated in an interview

that there was a small tunnel leading

off from the basement in the direction of

a house located directly across the

street, and that his wife had fallen into a

hole in the yard that presumably was a

collapsed portion of the tunnel.50

Although the building may predate the

Civil War, the basement has been re-

modelled and the house across the street

no longer exists.

17. The Deer Lick Farmhouse

This house, located approximately two

miles southwest of Burbank at the

northern edge of Wayne County, is a

local favorite for rumors of secret con-

struction related to the underground

railroad. Built by a wealthy railroader fol-

50. Interview with William Firebaugh,

January, 1991.

116 OHIO HISTORY

lowing the California Gold Rush of 1849,

the farmhouse is alleged by a long-

time local resident to have had a tunnel

leading from a fruit cellar to an out-

building; the entrance was said to have

been concealed by a movable wooden

shelf.51 Visual inspection

showed no tunnel, sealed entrance or evident re-

modeling of the basement.

Although the evidence provided by these

investigations does not, and can-

not, prove that participants in the

underground railroad in these Ohio counties

never constructed special places of

concealment for fugitive slaves, it suggests

that if such constructions existed at

all they must have been extremely rare.

The accounts left by both agents and

fugitives involved with the underground

railroad show that while discretion

needed to be practiced, especially after the

Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which gave

increased sanction to the searching of

premises, there was seldom excessive preoccupation

with secrecy on the part

of the abolitionists who were involved,

and little or no concern to construct

special hideaways for the fugitives.

If the agents of the underground

railroad rarely constructed secret chambers

or escape tunnels, how were transient

fugitives accommodated? Mordecai J.

Benedict recalled in later life that

during his boyhood in an active anti-slavery

Quaker settlement at Alum Creek, in

Morrow Co., prior to the Civil War, he

had "seen the floors of the

sitting- and dining-rooms [of his parents' house]

covered with the forms of sleeping

Negroes when he came downstairs of a

morning."52 The

homestead of Aaron Benedict, built at Alum Creek in 1857,

was a station where, in situations of

potential danger, Benedict simply moved

the fugitives to a barn or to

outbuildings across the creek.53 Benedict's

relative Griffin Levering sometimes

temporarily housed fugitives in his

cellar, but without any reported

attempts at special concealment. Even in

situations where concealment was

essential, fugitives who were given

overnight accommodations were generally

quartered in common places such as

an upstairs bedroom, a cellar, an attic,

a hayloft, an outbuilding, or even in a

nearby field or woods. Levi Coffin,

whose autobiography describes authentic

activities of the underground railroad

in Indiana and Ohio, says nothing about

constructing escape tunnels or secret

chambers, but speaks characteristically

of the use of existing household

facilities:

Our house was large and well adapted for

secreting fugitives. Very often slaves

would lie concealed in upper chambers

for weeks without the boarders or frequent

visitors at the house knowing anything

about it. My wife had a quiet unconcerned

way of going about her work as if

nothing unusual was on hand, which was calcu-

51. Interview with Gary Gallion, March,

1991.

52. Siebert, "A Quaker Section of

the Underground Railroad in Northern Ohio," 481.

53. Ibid., 482.

Subterranean Hideaways

117

lated to lull every suspicion of those

who might be watching, and who would have

been at once aroused by any sign of

secrecy of mystery. Even the intimate friends

of the family did not know when there

were slaves hidden in the house, unless they

were directly informed. When my wife

took food to the fugitives she generally

concealed it in a basket, and put some

freshly ironed garment on the top to make it

look a basketful of clean clothes.

Fugitives were not often allowed to eat in the

kitchen, from fear of detection.54

The abolitionist John Finney, who

maintained an underground railroad station

at his farm in Richland County, on at

least one occasion provided accommo-

dations for women fugitives in the loft

of his house and men in his barn.55

Examples of such common sense activities

could be multiplied.

Further evidence comes from the

fugitives themselves, some of whom later

recounted their long and arduous treks

toward Canada across fields, forests and

rivers, as well as through unfamiliar

and often hostile regions. The numerous

accounts of their experiences amassed in

Drew's The Refuge and Still's The

Underground Railroad, as well as ones found in many scattered publications,

incontestably reveal not only how

comparatively few slaves were assisted by

the underground railroad but also how

insignificant a role-if indeed any at

all-secret chambers and tunnels played

in their journeys to freedom.56 The

fugitives needed, to be sure, to draw as

little attention to themselves as possi-

ble, but most often seem to have found

impromptu accommodations on their

own initiative.

Knowledgeable examination of buildings

alleged to have features con-

structed for the concealment of fugitive

slaves constitutes a useful check on

the claims of oral tradition.

Investigation of this kind is particularly impor-

tant at the present, when an increasing

number of putative stations on the un-

derground railroad are being registered,

remodelled and opened to a paying pub-

lic, sometimes replete with guided tours

that feature secret compartments or

passages. The risk of creating places

and events not as they were but as they

exist in faded memories and romantic

imagination is a continuing danger in

the reconstruction of the history of

the underground railroad.

54. Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of

Levi Coffin (Cincinnati, 1898), 301. In one early instance

Coffin and his wife hid a negro man

"in a feather bed" (ibid., 151).

55. A. J. Baughman, "The

Underground Railway," Ohio Archaeological and Historical

Publications, 15 (1906), 190.

56. Benjamin Drew, The Refugee; or,

the Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada, Related

by Themselves (Boston, 1856); William Still, The Underground

Railroad, a Record....

(Philadelphia, 1872). Still was

concerned, among other things, to emphasize the initiative of the

fugitives and their relative

independence from the patronage of white sympathizers along their

journey, and thus serves as a corrective to the

exaggerated claims that some abolitionists had

made about the numbers of slaves that

they had assisted in maintaining underground railroad

stations.