Ohio History Journal

|

Rutherford B. Hayes and JOHN SHERMAN by JEANNETTE PADDOCK NICHOLS |

|

|

|

At noon on Wednesday, January 18, 1893, the United States Senate con- vened and, according to custom, heard a brief opening prayer by the Chap- lain. When Dr. J. G. Butler had finished, the senior Senator from Ohio, John Sherman, addressed his colleagues: Mr. President, it becomes my painful duty to announce to the Senate the death of Rutherford Birchard Hayes, at his residence in Fremont, Ohio, last evening at 11 o'clock. . . . It was my good fortune to know President Hayes intimately from the time we were law students until his death. To me his death is a deep personal grief. All who had the benefit of personal association with him were strengthened in their appreciation of his generous qual- ities of head and heart. His personal kindness and sincere enduring at- tachment for his friends was greater than he displayed in public inter- course. He was always modest, always courteous, kind to every one who approached him, and generous to friend or foe. He had no sympathy with hatred or malice. He gave every man his due according to his judgment of his merits. I therefore, as is usual on such occasions, move that the Senate, out of respect to the memory of President Hayes, do now adjourn.1 This was no routine eulogy. John Sherman spoke from the heart, much more feelingly than was his wont. The two politicians, near of age (Hayes seven months the senior),2 had known each other and had participated in the vagaries of political life in Ohio through half a century. Their particu- lar differences in temperament, opportunity, experience and abilities had been of sorts that enabled them to build and maintain through the decades NOTES ON PAGE 197 |

126 OHIO HISTORY

mutual feelings of respect and liking.

Their relationship flowered into a

lasting affection that came easily in

the life of Hayes, more rarely in that

of Sherman.3 The strains so

common between presidents and cabinet mem-

bers were minimal between these two.

Their mutual regard was due in part

to the fact that their respective

ambitions approached fruition at junc-

tures when fulfillment could be

complementary rather than antagonistic.

This was in marked contrast to the tides

of fate which upon occasion made

rivalry a frequent factor in relations

between Ohio's longtime Nestor at the

National Capitol and such ambitious

shorter-term politicos as Garfield and

Foraker, for example.4

To understand the foundation on which

the President and his Secretary

of the Treasury built their warm

relationship it is necessary to note various

episodes and to compare their

experiences as fellow-Ohioans. Sherman's

admission to the bar at the age of

twenty-one in 1844 had been preceded by

schooling no higher than an academy and

by private law instruction from

friends and relatives in Mansfield. At

this county seat he engaged actively

in legal practice. There he had emerged

as a "self-made" man, a keen stu-

dent of finance and politics known for

his competence and dignity. Since

he lacked easy warmth of manner,

however, his political advancement was

based more on respect for his ability

than on the comraderie easy for per-

sons of less reserve. He had cultivated

Whig affiliations until he helped to

found the Republican party and won

(1854-1860) four elections to the na-

tional House of Representatives.5

On the other hand, Hayes graduated from

Kenyon College and Harvard

Law School before he was admitted to the

bar in 1845 in his twenty-third

year, and later enjoyed at Cincinnati

more than a decade of law practice.

There he had emerged a person of modest

ability, firm in his beliefs, ambi-

tious but chary of antagonisms, and

pleasant in his dealings. He had won in

1858 a single term as City Solicitor,

but his frequently Democratic area pre-

vented a second term.

Thus, prior to the Civil War, Sherman

had acquired six years of ex-

perience in successfully wooing the Ohio

voters while becoming a notable

Republican leader on the national scene,

but Hayes thus far had not gone

much beyond the confines of a city

victory. Then came the accession of Lin-

coln and the Civil War, which altered

the political destinies of each man.

The elevation of Senator Salmon P. Chase

to Lincoln's cabinet enabled

Sherman (after a hard fought caucus

struggle)6 to leave the House for the

Senate, and Lincoln was moved to ask him

not to leave that chamber for an

army post. Sherman had become engrossed,

before the called summer ses-

sion of 1861, in unpaid service as a

colonel of Ohio Volunteers. The Presi-

dent felt he needed senatorial

leadership on Capitol Hill no less than mili-

tary leadership on the Virginia slopes.

To a man who had amply demon-

strated his legislative skill--by forcing through the

presecession House ap-

propriations essential to the federal

government--Lincoln's call to battle

for wartime financial legislation on the

Senate level could not be without its

personal and patriotic challenge.7 But

Sherman acceded to Lincoln's re-

HAYES and JOHN SHERMAN 127

quest before he had ever led a charge in

uniform. His return to service in

the toga cheated him of the military

identification acquired by Garfield and

many other men, who would find it

helpful in later political warfare.

Hayes, on the other hand, left the law

court that June for what proved

to be extended military service,

beginning as a major of Ohio Volunteers.

His tour of duty carried him into the

not-too-horrendous8 campaigning in

West Virginia. He had won recognition

for bravery and suffered three bat-

tle wounds when Ohio voters elected him

to Congress in 1864, at the mo-

ment he was promoted to brigadier

general. By the time of the official be-

ginning of his congressional service in

December of 1865, he had won a

brevet of major general and numerous

military friendships which were cher-

ished by him ever after.9

The importance of military insignia to

Ohio's Republican party in the

post-Civil War period scarcely can be

overestimated. All but two of its

gubernatorial candidates between 1865

and 1903 possessed war records, as

did all but four of the men actually

elected to that office. "Lesser offices

reveal a similar situation."10 On

the national level, James G. Blaine was

the only Republican candidate for

President between Lincoln and William

Howard Taft that did not possess

military experience. Sherman later com-

plained that his lack of war service was

responsible, in part, for his failure

to obtain the presidential nomination,

which lie sought three times.1l Colo-

nel John Sherman gave his sword, sash

and epaulets, which he wore so

briefly in mid-summer of 1861, to the

then Colonel Tecumseh Sherman;

and by the irony of fate that brother

later enjoyed the refusal of the high

office the Senator desperately craved.

Military insignia was the more precious

because of the continual can-

nonading on Ohio's political front, both

between parties and within them.

Divisiveness was indigenous to that

state, born of the original disparate im-

migration, nurtured by different

sectional reactions to political, economic

and social change, and perpetuated by an

incessantly revolving political cal-

endar. Politicking could hardly pause.

Partisans battled over the choice of

governor and legislature in odd-numbered

years, scarcely waiting to whet

their knives before renewing the fray

over congressional nominations in

even-numbered years and indulging in the

highest pitch of rivalry in their

quadrennial presidential canvasses.

More fertile soil for controversy hardly

could be found; in it Hayes and

Sherman cultivated their careers,

becoming political veterans of different

sorts. In due time Hayes tended to

become more palatable to the so-called

"liberals" and Sherman to the

"conservatives." But both established records

of cautious party regularity which

tended to protect their eligibility in fac-

tional contests. To both of these

ex-Whigs the Republican party was an

article of faith. On the whole, Hayes

proved to be the more fortunate, be-

cause his principal opponents until 1876

were mainly candidates of the op-

posite party; Sherman's were candidates

within his own party from the mo-

ment he became an aspirant for the

Senate.

It can be said that Sherman got, and

kept, his grip on the senatorship

through the medium of Ohio's chronic

disunity. In 1861 the refusal of

128 OHIO HISTORY

radical and conservative Republicans in

the state legislature to come to cau-

cus agreement among three older, leading

contestants gave the nomination

on the seventy-eighth ballot to Sherman

as a middle-of-the-road, compromise

candidate. When his term neared an end

in 1865, luck was on his side.

Sherman's party--then calling itself

"Union"--was split over the issue of

Negro suffrage, which might cost it victory.

This was the parlous situation midsummer

of 1865 when Sherman jour-

neyed down to Cincinnati, and found

occasion to call at the office of Con-

gressman Hayes. The Senator there

learned that the General could not yet

quite take party antagonisms in stride.

Hayes, unlike Sherman, had not been

tried in the fires of ten years of

bitter prewar and wartime political infight-

ing. Also, he was aggravated by the

premature patronage clamor with which

constituents can impatiently pester a

member of Congress even before he

takes his seat. Altogether, the job of

Representative seemed less likely to

prove satisfying than had leading troops

in the field. In this state of mind

Hayes confided to his Diary, after

Sherman had departed that July day,

"'Politics a bad trade' runs in my

head often. Guess we'll quit."12

But Hayes did not quit. The fledgling

Representative had found some-

thing of a mentor in the experienced

Senator. They shared the ardors of

that campaign--and others to follow.

That summer Hayes could observe

how Ohio's Republican factionalism could

be mitigated by an even greater

lack of finesse in Democratic counsels.

Vallandigham in 1865 was leading

the Democracy to campaign for

conservative reconstruction, which then

helped the Sherman men to shift their

emphasis to anti-Copperheadism.

With this safer issue the Unionists won

control of the legislature by a two

to one margin.13 But the total situation

remained such that the Unionists

did not long indulge any latent

propensity for an intra-party knock-down,

dragout fight over which one of the

party faithful should get the plum. Al-

though Radical members from the Western

Reserve now found Sherman

too conservative for their tastes, and southern

Ohio thought it was their

turn, and adherents of Sherman's

colleague, Benjamin F. Wade, feared

Sherman's selection would jeopardize

Wade's renomination next time, only

two ballots were needed to name Sherman

in 1865.14

Actually Ohio was a political

battleground so closely fought that no sen-

atorship could be a sinecure. Sherman's

experience in garnering six elec-

tions to the Senate demonstrated the

fact. Each time the legislature was to

select a colleague for him, from 1867 up

to 1897, the Democrats contrived

to be in control with the result that he

never had a Republican colleague

after Benjamin F. Wade lost out in

1867.15 On the other hand, when the

expiration of a Sherman term approached,

the Republicans managed to be

in a position to name the Senator, but

their disunity was such that the va-

rious internal factions did not combine

effectively on a nominee to dis-

place him. Of such factors--not too

reassuring--was Sherman's luck com-

posed.16

Hayes also found Ohio's mercurial

politics an advantage at times. As the

General won a reputation of being the best Republican

vote-getter,l7 his

eligibility for party nominations rose.

He wrote of his satisfaction in the

HAYES and JOHN SHERMAN 129

victorious campaign of 1866 which

brought him his second term in the

House; but his doubts about the joys of

being a congressman returned.18

Before his new term had fairly begun, he

was glad to resign it to accept

nomination to the governorship. As

Governor of Ohio for two consecutive

terms, Hayes became well and favorably

known far beyond his Cincinnati

congressional district. Since the legislature

was Democratic in his first term,

this fact seemed to free him from blame

for its sins of omission and com-

mission; but it lessened the influence

of Ohio Republicans in Washington

by enabling the Democrats to give

Sherman a Democratic colleague.19

At the same time the Republican party

was losing power in Ohio. In

1868 three of its congressmen lost their

seats, and eight scraped through by

majorities under one thousand votes. In

1869 Hayes's plurality was but 7500

votes, and his own Hamilton County Republicans

sent to the legislature a

contingent of reformists possessed of

the balance of power in both houses

and not above cooperating with

Democrats. The Reserve also sent some men

of liberal leanings; but they, like

their favorite Representative Garfield,

thought twice about possible future

punishment for party disloyalty.

Exposure of the corruption in the Grant

administration forced Hayes

and Sherman, both of them party

loyalists, to walk a tightrope. When Gov-

ernor Hayes was invited to attend a

conference of liberals held in Wash-

ington April 19-20, 1870, he stayed home

at Columbus for he "wanted no

new party and would have nothing to do

with organizing a new one."20

Sherman for his part habitually

accommodated himself to temporary shifts

in political winds, but he kept within

the boundaries of a cherished com-

mitment to a Republican majority,

thereby suffering the wrath of conserva-

tives who hated his concessions to

liberals, and of liberals who denounced

him as tarred with Grantism.

The positions of both Governor and

Senator, concerned for Republican

success, remained uncomfortable.

Although their party had won fourteen of

Ohio's nineteen congressional seats in

1870, and both the governorship and

lieutenant-governorship in 1871, Ohio's

incoming legislature that fall con-

sisted of an evenly divided upper house

and an assembly in which the fifty-

seven Republicans facing the forty-eight

Democrats included men of di-

vided loyalties. This body would

determine, in January of 1872, whether

Sherman might succeed himself. Hayes,

Garfield and others were approached

by Sherman's enemies to help unseat him.21

Here arose the first crisis in the

friendship between Hayes and Sherman.

To the delight of Democrats, the faction

opposing Sherman denounced him

as "utterly corrupt";22 they

sought to oust him, even if he won in the party

caucus, which was generally conceded to

be his during late 1871. Rumors

were rife that the dissidents would stay

out of the caucus to be free of its

mandate, and with Democratic cooperation

would get a majority for a com-

promise candidate on the day when they

voted in the legislature itself.

Hayes at first refused to believe the

rumors and then declined to be a candi-

date under a Democratic-Republican

endorsement. When the caucus finally

convened Thursday, January 4, 1872,

Sherman won easily, 71 to 4, with

most of the dissidents voting for him although some

claimed "they were

130 OHIO HISTORY

not to be bound by the result."23

Under these circumstances talk of a Hayes,

Garfield, or other candidacy persisted.

Hayes lightened the tension perhaps

by giving a reception Monday evening for

the incoming Republican gov-

ernor, General Edward F. Noyes. It was

attended by the warring factions

and described by Hayes as "A very

lively, happy thing."24

Late on Tuesday evening two

Republicans--a state senator and a repre-

sentative--rang Hayes's doorbell. They

assured him that enough new coali-

tion votes would materialize Wednesday

to make him United States Senator

and that this would guarantee him the

next presidency of the United States.

Luckily for Sherman the ambitions of

Hayes and Garfield were less strong

than their fears of the effects which

disloyalty to their party's caucus would

have upon the future of their party and

themselves. Hayes made it clear

that he would not consent to be a

candidate other than through regular

caucus endorsement. His two callers

departed, only to be followed by a

final suppliant, who insisted that his group now had

the votes to elect Hayes.

But the Governor, answering the doorbell

at midnight, standing in his

nightshirt, stood his ground. This with

a firm finality which his garb could

not diminish.25

Next day the roll call in the

legislature gave Sherman a majority, overall,

of only six votes, and some members

hastily undertook to switch. An alert

lieutenant-governor quickly declared

Sherman "duly elected." Afterward

Sherman claimed that he had had enough

Democratic promises to over-

balance Republican losses in any case.26

The crucial moment had been

Hayes's refusal; the rest was

anti-climax. To Hayes, Sherman was now much

in debt.

The Senator was destined to repay it,

and at a high rate of interest; but

an unpleasant misunderstanding marred

their relationship soon after

Grant's second inauguration. The eager

Republicans who on January 9,

1872, had dangled before Hayes the

presidency of the United States proved

unable to give him, on October 8

following, even so modest a place as a

seat in the House of Representatives of

the Forty-Third Congress. The party

phalanx which swept the state for Grant

included Hayes, Sherman and Gar-

field, but they could not stem a strong

Democratic tide in Hayes's district.

This rejection inflicted upon the

reputed "best vote-getter" his first ex-

perience with defeat for an important

office; it may have made him unwont-

edly sensitive.

At any rate, Grant in March of 1873 sent

the Senate hasty nomination

of Hayes for a position he did not

expect, had not applied for, and did not

much desire--that of Assistant Treasurer

at Cincinnati. The nomination

caught Ohio's Republican Senator, under

whose purview such matters must

come, off base. The outgoing and

incoming Secretary of the Treasury

(George S. Boutwell and William A.

Richardson) had both assured Sher-

man that necessary preparations under

the law were such that no appoint-

ment need be made until June 1; on this

understanding he had assured sev-

eral applicants that no choice would be

made until they had had a fair op-

portunity to present their

qualifications. He would be charged with mis-

HAYES and JOHN SHERMAN 131

leading them if the Hayes appointment

went through earlier. Therefore,

when the matter came up in executive

session, he asked that it go over. All

this Sherman explained to Hayes,

assuring him that he would "heartily and

cheerfuly concur in your appointment."27

But by an irony of fate damage had been

done. Hayes's pride was

wounded by postponement of a place which

he might have declined even if

confirmed. Tempermentally inclined to

over-simplification of patronage

problems it was hard for him to

"comprehend the crochet of Mr. Sherman."

Although he absolved Sherman of personal

hostility, he replied quite can-

didly. "The action taken was

calculated, although not so intended, to in-

jure me and to wound my feelings and

frankness required that I should

say that I think you were in error in

your views of duty under the circum-

stances."28

Fortunately, neither Hayes nor Sherman

made the prime political mis-

take of cherishing personal

misunderstandings. The campaign of 1874 found

them appearing together amiably, with

Hayes according Sherman high

praise for straightforward presentation.

The next year, when his party for

the third time nominated Hayes to wrest

the governorship, from a Demo-

crat, he especially sought Sherman's

company on the stump, in preachment

against the fiat money tenets of the

incumbent governor, William Allen.29

They managed to squeak through, by 5544

votes; but Sherman was appre-

hensive lest Republican disunity enable

the Democrats to capture the presi-

dency in the 1876 election and undo

gains obtained through the Civil War.

Thus he called on Ohio Republicans to

give Hayes a united delegation at

the national convention, because he

could "combine greater popular

strength and greater assurance of

success than other candidates." Though

not "greatly distinguished" as

a general or as a member of Congress, he was

"always sensible, industrious and

true to his convictions and the principles

and tendencies of his party." As

governor, he had "shown good executive

abilities." Moreover he was

"fortunately free from the personal enmities

and antagonisms that would weaken some

of his competitors."30

Such arguments, pressed by Sherman upon

Senator A. M. Burns of the

Ohio legislature in a letter of January

21, 1876, gained force. Ohio was

actually a unit bloc at this national

convention, which met, luckily for

Hayes, in Cincinnati.31 That

body, after wrangling over Blaine and his

chief competitors through six ballots,

on the seventh, adopted Sherman's

reasoning and chose Hayes. Fortunately

Sherman was spared the foreknowl-

edge that Hayes's most valuable

asset--his current lack of enemies--could

not work for himself in 1880.

Indicative of the affinity in 1876

between these two politicians was the

interchange which ensued. Hayes wrote

Sherman June 19:

I trust you will never regret the

important action you took in the in-

auguration and carrying out the movement

which resulted in my nom-

ination. I write these few words to

assure you that I appreciate and am

grateful for what you did.32

132 OHIO HISTORY

Sherman replied by hand on Senate

Chamber notepaper next day:

Your kind note is rec'd for which accept

my thanks. The importance

of your nomination was with me a

mathematical deduction and if any

outside fact gave color to my reasoning

it was your honorable & proper

course when during my last canvass for

Senator you refused to accept

the benefit of a small defection of a

few political friends. I am more

than happy when following reason and

duty to recognize also a per-

sonal kindness. We opened the campaign

here gloriously last night &

the acquiescence in your nomination is

general and hearty.33

Acquiescence in Hayes's election was destined,

in many areas, to be

neither general nor hearty, a fact which

put Hayes in debt to Sherman and

took toll of Sherman's political future.

The incoming President would not

infrequently find useful to him his

personal and political ties to his Secre-

tary of the Treasury, but the bond would

not always operate to the per-

sonal and political advantage of his

exceptionally faithful servitor.

Election evening, November 7, brought

dismay to both men; they went

to bed thinking Tilden had won. But

before dawn an unwary Democratic

official asked the editors of the New

York Times (a Republican group) for

an estimate of Tilden's votes, thus

suggesting that the Democrats were un-

sure. Before sunrise the editors were

communicating with "Zack" Chand-

ler, chairman of the Republican national

committee; they persuaded him

to telegraph the Republican leadership

in each of the three key states:

"Hayes is elected if we have

carried South Carolina, Florida and Louisiana.

Can you hold your state? Answer at

once." Whatever their answers, Chand-

ler a few hours later boldly told the

press: "Hayes has 185 votes and is

elected." This would leave Tilden

with only 184. Next the Republicans had

to make good Chandler's brashness.34

Both sides sent "visitors" to

watch the count of votes in each of the three

states. Louisiana was the most doubtful

and Grant asked Sherman (and

others) to hurry to New Orleans. After

stopping at Columbus to see Hayes

and at Cincinnati to meet other of Ohio's

emissaries, Sherman entered upon

"a long, anxious and laborious time

in New Orleans."35 Soon he was re-

porting to his wife Cecilia his

unhappiness over his assignment and a sharp

prescience of consequences to himself.

I have been assigned a much more conspicuous position here than I

wished and am almost sorry that I came.

We are acting only as witnesses

but public opinion will hold us as

partisans. . . . This whole business is

a thankless, ungracious task not free

from danger entirely unofficial

and at our individual expense. . . . I

frequently regret that I ever came.

Grant in 8 years did not remember my

existence until he had this most

uncomfortable task to perform and then

by his selections forced me to

come. I am carefully studying the case

as it is developed and will say

what I think is true without fear or

favor. . . . We have done nothing

of which we need to be ashamed.36

The Republicans had been shamed before

the nation by the exposure of

corruption in Grant's entourage and

Sherman was one of the party's leader-

HAYES and JOHN SHERMAN 133

ship who feared such vulnerability. As

Hayes phrased their mutual appre-

hension: "You feel, I am sure, as I

do about this whole business. A fair

election would have given [it to] us but

. . . there must be nothing crooked

on our part."37 Down in Louisiana

the intimidation on both sides which

had marred the casting of ballots made

itself felt in the counting of them.

Two government employees, testifying

before the Returning Board about

coercion by the Democrats, demanded of

the worried chairman of the Re-

publican "visitors" a written

guarantee of future employment outside the

state.

The age-old obligation for each party to

take care of its faithful had been

sanctified by immemorial custom; but

these employees required a pledge

in writing, which is not so customary.

To this the badgered chairman, over-

estimating their party loyalty, acceded.

Within a twelve-month he and Hayes

would rue this documentary testimonial

to pressure, which confirmed Sher-

man's prediction that "no

good" could come of the visitation.38

Numerous messages passed back and forth

between New Orleans, Colum-

bus and other centers, often in code;

and at long last Sherman, Garfield

and four companions stopped in Columbus

on December 4, enroute to

Washington. In the governor's office

that afternoon the cautious Hayes

polled each man individually. As he

reported in his Diary, "All concurred

in saying in the strongest terms that

the evidence and law entitled the Re-

publican ticket to the certificate of

election, and that the result would in

their opinion be accordingly." At

the gubernatorial mansion that Monday

evening the Governor and his Lady

entertained the emissaries with "a jo-

vial little gathering."39

Not so jovial was the atmosphere Sherman

found in Washington on Tues-

day, the second day of the final session

of the Forty-Fourth Congress. That

body was scheduled to meet in February

in joint session to attend the open-

ing of the electoral certificates by the

president of the Senate and the count-

ing of them. But who should count them?

The House was Democratic 168

to 107, and the Senate Republican 43 to

29 with two Liberal Republicans.

On a joint ballot Hayes would lose.40

He might win, however, if the Senate's

presiding officer could determine

which of the four sets of conflicting

returns-from Oregon, Florida, South

Carolina, and Louisiana--should be

counted. This was the solution favored

by Sherman and Hayes. The Senator, as a

quasi-agent of Hayes, participated

to some extent in weeks of discussion aimed at securing

Democratic consent

to this method of counting. Sherman was

one of the negotiators who con-

ferred with important southerners, many

of them Old Whigs, arguing that

Hayes--like Sherman an Old Whig--would

do more for them than Tilden

who opposed appropriations for the

internal improvements badly needed

by the devastated South. A Hayes

administration, it was proposed, would

remove federal troops from the South and

give it a place in the Cabinet,

besides granting more patronage, funds

for railroads and other improve-

ments, engineered with the help of

Garfield, as the proposed Speaker of the

House.41 This planning proved

to be an exercise in futility. It suggests an

unwarranted hopefulness on the part of

Sherman and Hayes. Much of the

134 OHIO HISTORY

proposed program could not be

implemented, although Hayes would prove

able to fulfill part of it.

In the meantime, a committee from each

house had been working to-

gether. The members intended to take

matters out of the hands of the

group affiliated with Hayes and Sherman.

As a result of their efforts, a bill

emerged to create an

extra-constitutional electoral commission to which

Congress, acting in joint session, would

refer conflicting sets of returns. Its

decisions need be accepted by only one

house to become final. This com-

plicated measure, which Sherman and

Hayes disapproved as risky for him,

invited filibustering which delayed its

enactment until January 29. There-

upon the Electoral Commission was set up

with five Senators, five Repre-

sentatives and five Supreme Court

Justices, so selected as to give the decid-

ing vote to Justice David Davis, an

"Independent." Here the legislature of

Illinois intervened, electing Davis to

the Senate--with the result that a Re-

publican Justice, Joseph P. Bradley,

took his place. Thereafter the houses

and the commission went through the roll

of states, slowed by sporadic fili-

bustering.42

While the counting was in progress,

Sherman conferred with Hayes in

Columbus. He returned with the reputed

authorization to promise with-

drawal of the troops by Hayes--a promise

which Grant (to the surprise of

Sherman) already had given. After a

final intensive burst of filibustering

the announcement came of Hayes's

election at 4:00 A.M. on March 2.43

That same morning Hayes and his family

reached Washington where

Senator Sherman and his brother General

William Tecumseh Sherman

awaited them at the station, to welcome

them as house guests of the Senator

until after the formal inauguration.

Before noon Hayes called on Grant

and went with him to the Capitol where

(it is reported) they found the

Democrats cheerful and cordial as they

waited their pound of flesh. Satur-

day evening Grant gave Hayes the

customary state dinner, with the extra

precaution of a private swearing in, to

insure the nation a president during

the Sabbath intervening before the

formal inauguration on Monday, March

5.44

Sherman had had a hectic four months

since November 7, largely occu-

pied with labor on behalf of Hayes and

the party. What would be his recom-

pense? Hayes formulated a tentative

cabinet slate and after some hesitation

offered Sherman the Treasury.45

To a Senator with keen interest in na-

tional financial problems and long

experience in working upon them, the

opportunity to achieve further

distinction in the field was most attractive.

He might, on the other hand, have

considered potential hazards threaten-

ing the peace of mind and political

future of any member of a Republican

administration installed in 1877. There

were five hazards of major im-

portance: a Congress with a Democratic

majority in both houses in most of

the four years; the dubious title to the

throne; possible opposition to a con-

ciliatory southern approach; an

entrenched patronage system to resist civil

service reform; and, perhaps the

greatest obstacle, powerful resistance to a

"sound" dollar.

HAYES and JOHN SHERMAN 135

Any or all of these forces could

obstruct the path of a politician stumb-

ling along the boulder-strewn trail

toward the presidential eminence. They

could not wreck the future career of a

President such as Hayes, who ab-

jured a second term and therefore could

face with more composure the

slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.

What here follows is a summary of

the reactions of the President and his Secretary

of the Treasury to these five

basic problems.46

First, as to the primary handicap, the

Democrats held a majority in the

House all four years, and in the Senate

for the last two years. Hayes and

Sherman therefore could never plan

legislation in easy confidence of a co-

operative push into enactment;

compromise skills were prerequisite. This

disadvantage was compounded by the fact

that Republicans themselves

were not a unit in response to executive

leadership. Some of them openly

fought the Hayes administration in the

three fields it sought most to stress

--conciliation of the South, reform of

the Civil Service, and strengthening

of the nation's credit. Some of them

were ex-Republicans of whom Hayes

sadly observed to Sherman,"New converts

are proverbally bitter and unfair

to those they have recently

left."47 Under such party handicaps executive

achievements could not be numerous or

easy of accomplishment.

The lack of Republican cohesiveness was

due also, in part, to the second

handicap listed above, the clouded title

to the throne. Subsequent advanced

scholarship would conclude that Hayes

lost Florida (although he probably

was entitled to a favorable decision in

South Carolina and Louisiana) and

that therefore, instead of besting Tilden

by 185 to 184, he lost on the over-

all count by 181 to 188. The Democrats

during Hayes's administration loud-

ly proclaimed that they had been

cheated; they were only too happy to in-

stitute an investigation complete with

witnesses, documentation, and a ma-

jority report attesting the election of

Tilden. A report by the Republicans

held the contrary. Eager Republicans

subpoened Western Union "cipher

dispatches," using and preserving

those which revealed Democratic corrup-

tive practices.48 In the

course of these exposures Sherman's unwary pledge

to the two Louisiana office-holders was

revealed, to the disgust of the Presi-

dent and his Secretary.49

Before Democratic efforts to unseat the

administration lost momentum,

embarrassments for Hayes and Sherman

were further increased by their

own party's attacks upon the third

handicap--their conciliatory southern

policy which had included choice of an

ex-Confederate, David M. Key, as

Postmaster General. The removal of

fulltime troops from the South also

aroused Radical Republicans to

blistering denunciation for (supposedly)

undermining the structure of

Reconstruction erected by the sacrifice of the

Civil War. Hayes stood his ground, with

Sherman's endorsement, and occu-

pation of southern centers by federal

troops gradually ended.50

By an irony of fate the Hayes

administration and the South came to swords

points on a different aspect of federal

supervision not confined to the South.

Postwar laws had authorized supervision

of presidential and congressional

elections throughout the nation by

federal supervisors and marshals. The

136 OHIO HISTORY

Democratic majority, seeking local

control of elections, attached "riders"

to army and other appropriation bills,

prohibiting polling place use of any

part of the army. Hayes and Sherman

interpreted the riders as efforts to

reduce their party's influence at the

polls. A sharp four years' contest en-

sued marked by eight stout presidential

vetoes, none of them overridden.51

Administration confrontation with the

other two major handicaps--the

entrenched patronage system and the

resistance to strengthening the na-

tion's credit--gave Hayes and Sherman

repeated challenges and saddled

Sherman with enmities encumbering his

ultimate ambition.

Grantism had made the nation

corruption-conscious, and rumors grew

rife and ripe about its pervasive

presence. Prominent among proposed tar-

gets for reform were the New York,

Boston, and Philadelphia customs

houses, under control of the state

machines of Roscoe Conkling, Benjamin

F. Butler, and Simon Cameron. Conkling

had been uncooperative on

Hayes's nomination and election and his

bailiwick was selected by Hayes

as the first target, against Sherman's

wishes.52 Apparently it was not as badly

mismanaged as some other centers but a

special Jay Commission exposed

the facts with the result that the

collector Chester A. Arthur and naval of-

ficer Alonzo B. Cornell were removed.

But Hayes was not able to obtain

Senate confirmation of their successors

until February of 1879 and then

only through a thorough expose by

Sherman of the custom house scandals.53

The intervening period had been

characterized by wavering and equivoca-

tion among the principal actors with

Secretary of State William M. Evarts

involved in the political scheming. The

situation illustrated the great need

for civil service reform, the divisive

effect of the issue upon the party, and

the hard alternatives among which Hayes

and Sherman sought to make

selections.54

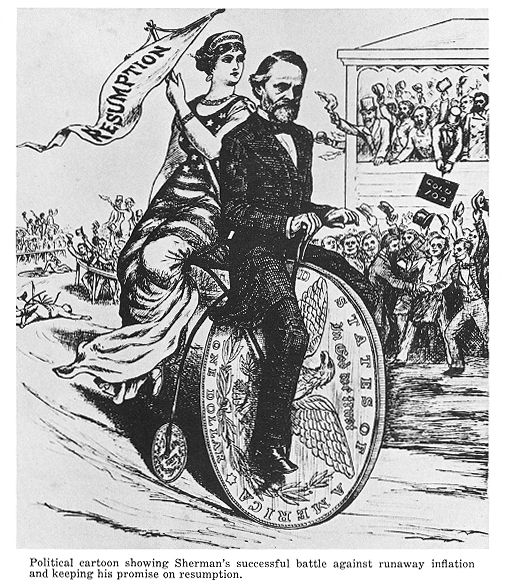

While all these hot political chestnuts

had to be handled, the fifth prob-

lem--that of the nation's credit--was

the hottest of all, particularly as the

nation was just emerging from a serious

depression. On this subject Sher-

man possessed a thorough knowledge and

broad experience acquired in

sixteen years of congressional handling

of it. Intimately involved in the

wartime establishment of the greenback

currency and the national banking

system,55 he now was

determined to protect the nation's credit by making

the greenbacks redeemable in gold (known

as resumption of specie pay-

ments) and by avoiding unlimited coinage

of cheap silver dollars.

Hayes stood firmly for resumption but

was so completely opposed to sil-

ver dollars that he vetoed the

compromise Bland-Allison bill that permitted

a limited issue of them. Not at all to

Sherman's surprise, Congress passed

the bill over the veto. This concession

to inflationary sentiment contributed

some quota to lessening the opposition

to resumption of specie payments

which Sherman achieved on schedule,

January 1, 1879, partly by virtue of

improving business trends and partly by

his own careful management of

Treasury bond issues and other

government resources.56

In his expert handling of this fifth and

greatest of the administration's

problems Sherman took great pride. He

felt that it in no small manner

|

HAYES and JOHN SHERMAN 137 |

|

justified his hope for the nation's highest award. Unfortunately, in securing a presidential nomination, merit and ability are less influential than a warm personality, united backing by one's state delegation, and a middle stance not too sharply identified with divisive issues. Of the first two assets, Sher- man had much.57 In regard to the last three far more important qualifica- tions, he was sadly lacking. Of hail-fellow-well-met cronies (military or leg- islative), this naturally-reserved gentleman had few. Of unity, the state's delegation was bereft by the refusal of nine Blaine men to unite in Sher- |

138 OHIO HISTORY

man's support as the state convention

had suggested; Sherman unfortunate-

ly selected Garfield (who gained

attention this way) as the one to nom-

inate him. Of a middle stance, Sherman

had deprived himself by contribu-

tions to the Hayes administration, by

his recent opposition to free coinage,

and by insistence upon resumption; all

this made the Secretary less "avail-

able" than men not as competent.58

Hayes did not publicly endorse Sherman,

feeling that interference by the

President would be "unseemly."

Perhaps he, better than Sherman, realized

that the Secretary was not

"available." Commenting in his Diary on nom-

ination developments, he casually wrote,

after mentioning Grant and Blaine,

"It may be Sherman or a

fourth--either Edmunds or Wilson."59 Garfield in

nominating Sherman said that he did not

present him "as a better man or a

better Republican than thousands of

others," and called for Republican

unity. A majority of the convention

proceeded (on the thirty-fourth bal-

lot) to unite on Garfield.60

To Hayes the Garfield nomination was

"altogether good," being a defeat

for Conkling and others who were

pressing a third term for Grant. But this

did not mean that the President was

indifferent to Sherman's future wel-

fare. Perhaps he felt that it now was

his turn to pay a debt. At any rate,

the final decision of the Ohio

legislature to give Sherman the Senate chair

which Garfield was relinquishing (as Senator-elect)

seems not to have been

unrelated to Hayes's desire that

Garfield should cooperate to that end.61

Sherman was deeply appreciative of his

endorsement by the Ohio legisla-

ture, unanimous this time. He went to

Columbus to tell them so, and in

so doing the Secretary of the Treasury

could be said to be thanking also

the President of the United States:

I can only say then, in conclusion,

fellow-citizens, that I am glad that

the opportunity of the office you have

given me will enable me to come

back here home to Ohio to cultivate

again the relations I had of old.

It is one of the happiest thoughts that

comes to me in consequence of

your election that I will be able to

live again among you and to be one

of you, and I trust in time to overcome

the notion that has sprung up

within two or three years that I am a

human iceberg, dead to all human

sympathies. I hope you will enable me to

overcome that difficulty. That

you will receive me kindly, and I think

I will show you, if you doubt

it, that I have a heart to acknowledge

gratitude--a heart that feels for

others, and willing to alleviate where I

can all the evils to which men

and women are subject. I again thank you

from the bottom of my

heart.62

THE AUTHOR: Jeannette Paddock

Nichols formerly was chairman of the

Graduate Group in Economic History at

the University of Pennsylvania.