Ohio History Journal

MARIAN J. MORTON

"Go and Sin No More": Maternity

Homes in Cleveland, 1869-1936

In 1869 the Woman's Christian

Association of Cleveland founded

the Retreat, the first of the city's

maternity homes and refuges for

women who had "lost the glory of

their womanhood."1 Its founders

sought to emulate Christ's injunction to

Mary Magdalen: "Woman,

sin no more; thy faith hath saved

thee."2 As its name suggests, the

Retreat was a shelter, a refuge, in

which the fallen woman, both vic-

tim and sinner, could be saved and

reclaimed through evangelical re-

ligion, the ministrations of pious

women, and the learning of domestic

skills and virtues. In 1936 the Retreat

closed, victim of the hard times

of the Depression, the rising costs of

medical care, and lessened de-

mand for the kind of services it

provided.

In the intervening years, five more

facilities for unwed mothers,

similar to the Retreat in their initial

goals and strategies, opened in

Cleveland: St. Ann's Maternity Home and

Infant Asylum in 1873; the

Salvation Army Rescue Home in 1892; the

Maternity Home in 1892;

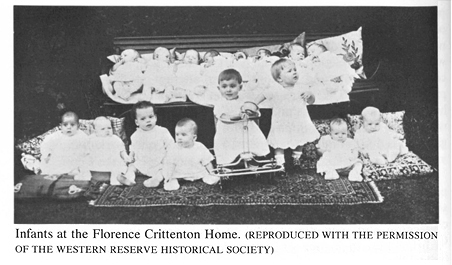

the Florence Crittenton Home in 1912,

and another Salvation Army

facility, the Mary B. Talbert Home, in

1925. All these institutions un-

derwent significant changes in the years

1869 to 1936. All joined the

Cleveland Federation for Charity and

Philanthropy, becoming part

of a network of secular social welfare

agencies and conforming to the

standards imposed by the Federation and

by Ohio laws regulating

maternity homes and hospitals. Fees and

admission policies were

standardized; their staffs became more

professional. All officially

adopted the current explanations for

unwed motherhood which at-

Marian J. Morton is Professor of History

at John Carroll University. This article was

written, in part, with aid from a

National Endowment for the Humanities summer

stipend.

1. Woman's Christian Association, Annual

Report 1870, 15, MS 3516, Western Re-

serve Historical Society. Hereinafter

this collection will be referred to as YWCA Cleve-

land, since the collection is titled

after the group's later name.

2. Mary Ingham, Women of Cleveland

and Their Work: Philanthropic, Educational,

Literary, Medical and Artistic (Cleveland, 1893), 151.

118 OHIO

HISTORY

tributed it to unwholesome environment

or mental deficiency; all

gradually shifted much of their

attention from the unwed mother to

her illegitimate child. Three homes

became hospitals, specializing in

obstetrical care.

In short, maternity homes reflected the

secularization and profes-

sionalization of benevolence and reform

during the first decades of

this century. However, despite the shift

from mission to medical fa-

cility, from pious volunteer to trained

social worker, the homes re-

tained much of the emphasis on

reformation which marked their

religious origins. Their objectives and

tactics remained remarkably

constant through the 1930s: to rescue

and save their erring inmates

by sheltering them from the vicious

world, to reclaim them for and

by the morality of middle-class

womanhood.3

The Retreat

The Retreat was a product of the

evangelical benevolence of post-

Civil War Protestantism and remained

true to this heritage through-

out its lifetime.4 The

Woman's Christian Associations in Cleveland

and elsewhere were formed as adjuncts to

the Young Men's Christian

3. On the professionalization and

secularization of benevolence and reform, see

Robert H. Bremner, From the Depths:

The Discovery of Poverty in the United States

(New York, 1956); Roy Lubove, The

Professional Altruist: The Emergence of Social

Work as a Career, 1880-1930 (Cambridge, Mass., 1965), and for a discussion of those

trends in Cleveland, Clara Kaiser,

"Organized Social Work in Cleveland, Its History

and Setting" (Ph.D. dissertation,

The Ohio State University, 1936). On the impact

of Federations of Charity and

Philanthropy, see Judith Ann Trolander, Settlements

Houses and the Great Depression (Detroit, 1975), which discusses Cleveland specifi-

cally. David J. Rothman in Conscience

and Convenience: The Asylum and Its Alterna-

tives in Progressive America (Boston, Toronto, 1980) describes attempts at institutional

flexibility during the Progressive

period, which I do not find in the maternity homes,

but concedes that the Progressives never

abandoned their moralistic approach to re-

form, 5-6, 52-53. Katherine G. Aiken,

"The National Florence Crittenton Mission,

1883-1925: A Case Study in Progressive

Reform" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of

Washington, 1980) also finds greater

change in the homes than I do. The penal institu-

tions described in Estelle B. Freedman, Their

Sisters' Keepers: Women's Prison Re-

form in America, 1830-1930 (Ann Arbor, 1981), sadly-and surely unintentionally-

most closely resemble Cleveland's

maternity homes during the period, 1869-1936;

these prisons, for example, encouraged

inmates to keep their children in order to de-

velop their own maternal instincts and

stressed moral, religious and domestic training,

89-96.

4. The founders of Cleveland's Retreat

resemble the "benevolent ladies" of Chi-

cago in their interests and activities,

as in Kathleen D. McCarthy, Noblesse Oblige:

Charity and Cultural Philanthropy in

Chicago, 1849-1929 (Chicago and

London, 1982).

On nineteenth century refuges, see

Steven L. Schlossman, Love and the American De-

linquent: The Theory and Practice of

"Progressive" Juvenile Justice, 1825-1920 (Chica-

go, 1977), 34-41.

"Go and Sin No More" 119

Associations. (The Cleveland WCA became

the YWCA in 1893.) In

Cleveland, for example, the founding of

the WCA was inspired by a

visiting YMCA speaker who urged those

women present to do "prac-

tical work."5 The YMCA's

promoted preaching and tract distribu-

tion but also built residential

institutions for young men in the city,

attempting there and with uplifting

classes to reach and teach up-

wardly mobile white-collar workers the

values of middle-class

Protestantism.6

The WCA shared this interest in

missionary work combined with

institution-building. The Retreat was,

in fact, the second institution

built by the Cleveland WCA, the first

being a home for young work-

ing women. The WCA's goals were broad

and all-encompassing:

"The spiritual, moral, mental,

social and physical welfare of the

women in our midst."7 Of

particular concern were "young women

who are dependent on their own exertions

for support,"8 who had

come to the city during the Civil War in

search of job opportunities

created by the War and by the city's

burgeoning economy. The

WCA founders were pillars of their

several Protestant churches, and

their first annual meeting in 1869 drew

600 interested Cleveland wom-

en. This group would remain in the

forefront of the city's female be-

nevolent and reform activities through

the 1930s.

The rationale for the Retreat stated

clearly its founders' percep-

tions of their less fortunate sisters'

moral and physical frailty: "In the

bustle and activity of the age, the

women are following hard after the

men. Not satisfied with their quiet

country homes, many of them

press their way to the cities. What should

be done to care for these

women? Be they never so pure, they are

liable to fall into disgrace

and sin, and they must be tenderly

watched over and cared for."9

Mary Ingham, participant in and

historian of many women's activities

in Cleveland, described the Retreat as a

"mission with the Scarlet

Letter,"10 revealing

both the religious purpose and the Victorian

sexual morality which would characterize

the home. The Retreat's

first nine inmates were described as

"well-behaved, industrious,

5. Mildred Esgar, "Women Involved

in the Real World: A History of the Young

Women's Christian Association of Cleveland, Ohio,

1868-1968," unpublished type-

script at the Western Reserve Historical

Society, Cleveland, Ohio, 35.

6. Charles H. Hopkins, A History of

the YMCA in North America (New York, 1951),

192.

7. Esgar, "Women Involved,"

41.

8. Ibid., 42.

9. YWCA, Cleveland, newspaper clipping,

1869, in scrapbook, Container 11.

10. Ingham, Women of Cleveland, 151.

120 OHIO HISTORY

and thankful for protection and

sympathy. They are being taught to

sew, to sing, and we trust, to

pray."11

Despite its religiosity, however, the

YWCA was never willing to

leave the fate of its clients solely to

God's will, nor to blame a wom-

an's loss of virtue solely upon her

moral weakness; hence, the persis-

tent concern with training women to earn

their own livings so that

they would not be seduced for money into

prostitution or sexual mis-

conduct. Given the limited options in

this period for women, espe-

cially working-class women, the YWCA's

emphasis on domestic serv-

ice and skills such as sewing and

millinery made sense. The

significance of the Retreat for the community

is indicated by the do-

nation to it of $400 from the Cleveland

city council although most of

its funding and donations always came

from private sources.12

The Retreat at first sheltered not only

unwed mothers but women

suspected or guilty of sexual

misbehavior. Their conversion was to

be achieved through Bible classes, daily

prayers, and the "Chris-

tian" atmosphere of the home. For

example, in 1873, according to a

newspaper description of the new

facility, its walls were hung with

"embroidered mottos: 'Through

Christ we hope,' 'God is our refuge

and our strength,' 'Christ for all, all

for Christ.' "13 Retreat

founders,

however, did not claim to work miracles,

noting sadly in 1872 that

some of the inmates had "returned

to their former lives of sin, and

that is the experience of every

institution, but a larger proportion than

heretofore have been saved."14

Retreat managers kept careful track of

their clientele. The 1882 fig-

ures, for example, show that 99 girls

were admitted during the year;

of these, 21 were "returned to

friends"; 24 were "furnished with sit-

uations" (domestic service jobs);

three were dismissed for bad con-

duct; one was sent to school; two were

married. Of the 54 babies

born, 27 were adopted, nine were taken

away with their mothers,

four died, and the remainder were still

sheltered at the home.15

These numbers indicate a rapid turnover

and a short stay for the girls

as well as the institution's role as an

adoption agency, for at this time

there were few other child- or

women-caring facilities in the city.

This situation would change dramatically

in the next twenty years.

As late as 1891, however, the Retreat

felt not only alone but embat-

tled in its mission to save fallen

women; their annual report com-

11. YWCA, Cleveland, Annual Report, 1870,

15, Container 8.

12. Ibid., 17

13. Ibid., newspaper clipping, no

date, in scrapbook, Container 11.

14. Ibid., Annual Report, 1872,

3, Container 8.

15. Ibid., "Minutes," November 7, 1882, Container 1.

"Go and Sin No More" 121

plained that philanthropists gave to

other institutions but not to the

Retreat: "Frequently we are asked,

'Do you not feel that you are en-

couraging vice while harboring,

sheltering, and protecting these

girls?' We are simply giving them a

chance to do better .... What

shall we believe but that the Father

mercifully pardons all our iniqui-

ties, transgressions, and sins?"16

By 1900 the Retreat described itself no

longer as a mission or a ref-

uge, but as a "reformatory home for

girls who are in absolute need of

shelter and friends."17 Applicants

were required to stay six months,

which would become standard policy for

all maternity homes. Refor-

mation presumably took longer than

simple conversion although the

Retreat's strategies were similar for

both. "We try to make our Home

the 'House Beautiful' of which we read

in Bunyan's Pilgrim's Prog-

ress, a haven between the Hill of Difficulty and the Valley

of Tempta-

tion. When the girls leave the home,

they are better armed for life's

difficulties than when they came to us,

having been taught, advised,

and shown the pathway to right

living."18

The lessened overt religiosity may have

been due to the establish-

ment of three competing maternity homes

and other hospital facilities

for unwed mothers by the turn of the

century. Equally significant,

the Retreat, like these other

institutions, sought the approval of the

Committee on Benevolent Associations of

the Cleveland Chamber of

Commerce. The Committee's approval

guaranteed an institution's re-

spectability and access to funding. This

Committee also set up the

Federation for Charity and Philanthropy

in 1913, which raised and

distributed funds for those of the

myriad of Cleveland charities

which met the Federation's standards.

For example, Federation

members were required to raise funds

from Clevelanders without re-

gard for "religious,

denominational, or other special affiliation."19

The Federation (which became the Welfare

Federation in 1917) in

turn formed the Conference on

Illegitimacy, which the maternity

homes joined and which had counterparts

in several other cities; its

purpose was to establish uniform and

sound policies for the care of

unwed mothers and their children. The

trend toward uniformity was

spurred also by the 1908 passage of an

Ohio law regulating maternity

homes and hospitals.

16. Ibid., Annual Report, 1891,

19, Container 8.

17. Ibid., Annual Report, 1900,

87.

18. Ibid., Annual Report, 1909, 11, Container 9.

19. Cleveland Federation for Charity and

Philanthropy, The Social Year Book: The

Human Problems and Resources of

Cleveland (Cleveland, 1913), 26.

122 OHIO HISTORY

These pressures for conformity were

illustrated in 1916 when the

Retreat's managers asked a panel to make

recommendations for the

home, presumably at the urging of the

Conference on Illegitimacy.

The panel commended the institution's

"cleanliness, home-like life,

and efficient management," as well

as its excellent infant mortality

record. However, if the home wished to

ensure being licensed, the

panel suggested that the girls be

required to undergo a Wasserman

test for venereal disease and that the

home employ a social case

worker to investigate "the stories

of the girls and their life after leav-

ing the place."20 The

managers quickly took steps to implement these

suggestions. In addition, reflecting the

prevalent view that "mentality

and morality were closely

connected," they planned to administer

mental tests as well. The Federation

agreed to help finance these ad-

ditional expenses.21

The Federation's Social Yearbook, published

in in 1913, indicated

the Retreat's growing specialization in

medical and child-care, two

further concerns of the Conference on

Illegitimacy: The Retreat's pur-

pose was to provide "medical and

surgical treatment of the unmar-

ried mother," and to help her to

"make the best possible plan for

the future of the innocent babe, whether

that be a life with the

mother, or in an adopted home deemed

worthy after careful investi-

gation." Yet the reformatory goal

remained, for the Retreat was also

to "bring [the unwed mother] to a

right view of life and a proper self-

respect, to start her in some honorable

way of self-support."22

In 1921 the Retreat, after building a

new facility, was incorporated

separately from the Cleveland YWCA, in

keeping with the YWCA

policy of encouraging its institutions

to become completely independ-

ent. The Retreat remained active in the

Conference on Illegitimacy

and worked with other social welfare

agencies such as the Cleveland

Humane Society, which was primarily a

child-placing agency, and

did the case work for the maternity

homes. The Retreat's regimen

broadened by the mid-1920s to include

some recreation and outdoor

games and classes by a visiting public

school teacher; there was still

instruction in house-keeping and

child-care. Like the other homes,

the Retreat still insisted that a woman

stay in the home with her

child for six months, partly because

this was felt to be healthier for

the child since the mother could nurse

it, but also because the care

of the child would aid in the

reformation of the mother: "this love

20. YWCA, Cleveland, Board of Trustees

Minutes, April 18, 1916, Container 2.

21. Ibid., October 17, 1916.

22. Cleveland Federation for Charity and

Philanthropy, The Social Yearbook, 61.

"Go and Sin No More" 123

for her child is a big element in

character-building-working for her

child gives the mother an aim in life

which makes her stronger."23

This belief in the redemptive quality of

mothering was shared by the

other maternity homes.

The Retreat's policies changed little in

the 1930s. Although "sec-

ond offenders" were no longer

turned away, Retreat managers ex-

plained that this was because such girls

could especially benefit from

the "care and training" which

the home provided. Mental and psy-

chiatric tests were required during the

six-month stay. The home

did not offer much vocational training

since most inmates had not fin-

ished grade school, but "all [were]

taught to sew.... During their

stay they [were] taught to darn, repair,

and make their own baby's

clothes [and] their own hats. We feel

that a girl gains much in self-

respect by being neatly dressed, and

that self-respect is a great step

in reformation."24

The Retreat had fewer and fewer inmates

during the early 1930s.25

In February, 1936, the Retreat's

representative to the Council on Ille-

gitimacy pled for additional financial

assistance, reaffirming the ne-

cessity of maternity homes where a girl

"would receive good care,

discipline, and training."26 Three

months later the Retreat closed its

doors forever.

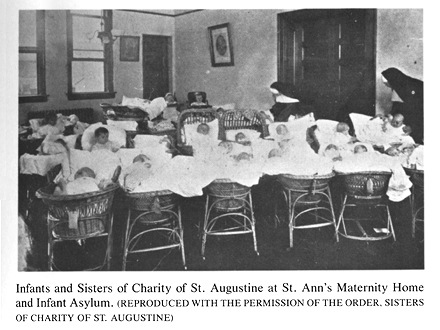

St. Ann's Maternity Home and Infant

Asylum

There are two versions of the first

patient at St. Ann's Maternity

Home and Infant Asylum; one describes

her as a "good respectable

widow," the other, perhaps more

accurately, simply as "an unwed

mother."27 Whatever the

precipitating event or person, the more

general explanation for the founding in

1873 of the maternity home

which became St. Ann's Hospital was the

growth of Cleveland's

Catholic population and the penchant for

institution-building of the

city's first Catholic bishop, Amadeus

Rappe. St. Ann's remained a

23. Federation for Community Planning,

Cleveland, Ohio (hereinafter referred to as

FCP), MS 3788, Western Reserve

Historical Society, Conference on Illegitimacy, De-

cember 14, 1925, Container 30, Folder

739.

24. Ibid., December 8, 1930,

Container 30, Folder 720.

25. Ibid., Children's Council,

Committee on Unmarried Mothers, August 14, 1936,

Container 33, Folder 829.

26. Ibid., February 5, 1936.

27. Sister Stanislaus Clifford,

"History," unpublished typescript in Archives of the

Sisters of Charity of St. Augustine, Mt.

Augustine Convent, Richfield, Ohio (hereinaf-

ter referred to as Mt. Augustine);

"Important Events, St. Ann's Hospital," unpub-

lished typescript, Mt. Augustine. Both

sources undated and unpaged.

124 OHIO HISTORY

Catholic service institution,

administered and controlled by religious

personnel and Catholic doctrine during

its century-long lifetime.

It was at Rappe's instigation that the

first four Sisters of Charity of

St. Augustine were persuaded to come to

the wilderness outpost of

Cleveland in 1851 from their native

France, where they had estab-

lished a tradition of nursing and

medical service. The small band of

nuns quickly established Cleveland's

first public hospital and an or-

phanage for boys. This hospital was

short-lived, but in 1865 in the

wake of the Civil War, the Order founded

St. Vincent Charity Hospi-

tal, still a major medical facility.28

The War had spurred the growth of

Cleveland's commerce and in-

dustry, and the city's population

doubled between 1860 and 1870.29

Many of these newcomers were Catholic,

straining the capacities of

the existing Catholic welfare

institutions. Cleveland's new bishop,

Richard Gilmour, saw the need for new

facilities, including St. Ann's.

Gilmour was initially reluctant to

endorse a home for unwed mothers,

feeling that this would suggest an

endorsement of unwed mother-

hood,30 but the city's

long-standing rivalry between Catholics and

Protestants helped change his mind.

According to one account, a

Catholic woman had been admitted to the

Retreat in 1872 and fallen

victim to its vigorous proselytising. As

she lay dying, a Catholic

priest, accompanied by her father,

sought admission in order to ad-

minister the last sacraments. However,

"both were denied admission

and were told at the door that 'the girl

had confessed her sins to Je-

sus!'"31 Gilmour's

response was to encourage the building of St.

Ann's behind Charity Hospital.

A Catholic maternity home could also be

justified by the

Church's opposition to birth control and

abortion, options more

available to non-Catholic women.

Accordingly, St. Ann's was also a

foundling home and orphanage, which

housed not only illegitimate

but abandoned and neglected children;

child-care would always be

an important part of the work of the

Sisters. From its founding to

1899, St. Ann's cared for 4000 children,

either born or placed

there.32

28. Donald P. Gavin, In All Things

Charity: A History of the Sisters of Charity of St.

Augustine, Cleveland, Ohio, 1851-1954 (Milwaukee, 1955), 3-20.

29. William Ganson Rose, Cleveland,

The Making of a City (Cleveland and New

York, 1950), 361.

30. Gavin, In All Things, 52.

31. Michael J. Hynes, History of the

Diocese of Cleveland: Origin and Growth (Cleve-

land, 1953), 168.

32. Gavin, In All Things, 71.

|

"Go and Sin No More" 125 |

|

|

|

St. Ann's intended to save both mothers and children. According to Sister Stanislaus, an early chronicler of the order's activities, in the hospital "mothers are shielded and helped to rise from their fall. . . . Rarely was it heard of after the house was opened that in- fants were destroyed by their natural mothers, or others, to conceal a crime; thus adding to their first sin, a second of murder."33 The ba- bies were baptized, unless they had been so before their abandon- ment. The mothers were proselytised as well. Although the women allegedly preserved their anonymity, they were the objects of the prayerful scrutiny of the nuns, "who not only bestow upon them tem- poral blessings but also fervently and silently pray that the fallen one, like Magdalen, may repent and return to grace."34 As the official his- torian of the Cleveland Diocese explained, in words that echo those of the Retreat managers, "A censorious world may say, this [materni- ty home] is fostering crime; but no, it is the Saviour's own method; 'Woman, neither will I condemn thee. Go, and now sin no more.' It

33. Clifford, "History," n.p. 34. "Woman's Work. The Noble Institution Conducted in Cleveland by the Sisters of Charity," unpublished typescript, 1893, at Mt. Augustine. |

126 OHIO HISTORY

saves many a poor victim from the scorn

of a pitiless world and keeps

the escutcheon of family honor

untarnished."35

St. Ann's, however, was also a medical

facility. In 1899 a school of

nursing was established with a specialty

in obstetric nursing.36 Al-

though closely connected with St.

Vincent Charity Hospital, St.

Ann's also developed links with the

Western Reserve University

Medical School by the early 1900s;

students from Western Reserve

were permitted to observe confinements,

and the hospital by-laws

stipulated that the resident physician

had to be a graduate of the

Medical School.37

St. Ann's had always taken a few married

patients, and this num-

ber grew as Cleveland's Catholic population

increased and as it be-

came more acceptable to give birth in a

hospital. Since many of these

married patients could pay, the hospital

encouraged their patronage,

but separated them from the unwed

mothers: "There is no inter-

course except going back and forth

through the yard." Neither did

the married women apparently need the

spiritual direction still of-

fered to their unmarried counterparts,

who once a month were urged

to go to confession and communion and

every evening went to chapel.

Some even joined the Sisters of the Good

Shepherd. Non-Catholics

were not required to attend religious

services, but there were proba-

bly few of these women.38 In

1918 a separate building, Loretta Hall,

was built for the unwed mothers, ensuring

that the married women

would not come into contact with less

virtuous womanhood.

Like the Retreat, St. Ann's joined the

Federation of Charity and

Philanthropy and the Conference on

Illegitimacy, which created

again the pressure to meet the

Federation's standards for child-and

maternal-care. St. Ann's also joined

Cleveland Catholic Charities

and sent representatives to the National

Conference of Catholic Char-

ities established in 1910. In many

respects, the Catholic Conference

adhered to secular social work

standards, emphasizing the desira-

bility of keeping mother and child

together for six months rather

than placing the child up for adoption.39

On the other hand, the

35. George F. Houck, A History of

Catholicity in Northern Ohio and in the Diocese of

Cleveland, Vol. 1 (Cleveland, 1903), 739-40.

36. Gavin, In All Things, 75.

37. "By-Laws Governing the Visiting

Staff of St. Ann's Infant Asylum and Maternity

Home," undated, in the Archives of

the Catholic Diocese, Cleveland, Ohio (herein-

after referred to as Diocesan Archives).

38. "Official Visitation of St.

Ann's Infant Asylum and Maternity Hospital, October

26, 1910," in Diocesan Archives.

39. Proceedings of the National

Conference on Catholic Charities (Washington,

D.C., 1910), 303.

"Go and Sin No More" 127

Catholic Church's stand on some issues

influenced its thinking on

maternity home policy. The Church, like

the Conference on Illegiti-

macy, supported the rights of the

illegitimate child to financial sup-

port from the father and at the same

time emphasized that it was

strongly opposed to pre-marital or

extra-marital sex and to the use of

contraceptives and abortion.40

Throughout the 1920s the medical focus

of the hospital sharp-

ened, particularly on its pediatric

care. St. Ann's specialized in the

care of premature infants, priding

itself on the special diet developed

by the chief of pediatrics.41

In 1926 Bishop Joseph Schrembs deed-

ed the hospital property to the Sisters,

who incorporated it separate-

ly from the diocese. The articles of

incorporation made clear the

medical orientation: "Said

corporation is formed for the purpose of

establishing, maintaining and conducting

a hospital for medical and

surgical treatments of persons,

conducting a training school for nurses

and granting diplomas to nurses

graduated therefrom; engaging in re-

search work in medicine, surgery, and

kindred subjects..., main-

taining a public dispensary and other

departments for social serv-

ice." 42

The "Golden Jubilee Bulletin,"

celebrating the hospital's fiftieth

anniversary, also noted that "To

the unmarried mother, who many

times spends from six to eight months in

the institution before her

delivery, splendid prenatal care is

given.... From the time of her

entrance she is under very careful

medical supervision."43 The intent

to reform and save, however, is evident

in the long confinement prior

to the woman's delivery, especially

since it was still considered desir-

able that she remain in the hospital for

six months after her delivery

as well.

The religious thrust of the Catholic

maternity homes in general and

St. Ann's in specific survived into the

1930s. A paper delivered be-

fore the National Conference of Catholic

Charities in 1931 spoke of

the objectives of the care of unmarried

mothers: "first, to safeguard

the faith and ensure the spiritual

welfare of both mother and child;

secondly, to effect a social adjustment

which will as nearly as possi-

ble restore normal conditions."44

In the same year, the director of a

40. Ibid., 1918, 166-68.

41. Ibid., 1925, 122;

"Important Events," n.p.

42. Letter to Reverend Mother M.

Clementine from George F. Quinn, January 8,

1953, in Diocesan Archives.

43. "Golden Jubilee Bulletin, St.

Ann's Infant Asylum and Hospital," 1923, n.p., at

Mt. Augustine.

44. Proceedings, 1931, 109.

|

128 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

Catholic maternity hospital in Pittsburgh explained illegitimate preg- nancy this way: "Many of these girls have become careless in their religious obligations, neglecting confession and Holy Communion, but after they have made their peace with God, that calm quiet con- tentment enters into their whole being-then they are ready to begin the uplift of their lives."45 Bishop Schrembs, commemorating the hospital's sixtieth anniversary in 1933, expressed sentiments which were reminiscent of the late nineteenth-century religiosity and Victo- rianism present at the maternity home's founding:the unwed mother, "more sinned against than sinned," would rather bear the shame of her illicit pregnancy than "stain her hands with the blood of her un- born child. The Church takes her in, lovingly throws the cloak of charity about her, shelters her from the scorn of the world and lets her bring forth her precious burden-even though that burden be the burden of sin."46 Although the Bishop's sermon should not be interpreted as des-

45. Ibid., 120. 46. "Excerpts from the address given by the Rt. Rev. Joseph Schrembs," unpub- lished typescript, 1933, at Mt. Augustine. |

"Go and Sin No More" 129

criptive of reality, other evidence also

indicated the lingering

strength of this desire to rescue the

fallen. The 1935 Report of the Di-

vision of Children of the Ohio

Department of Public Welfare de-

scribed St. Ann's large medical staff,

its case workers and resident

psychiatrist and an "institutional

and impersonal atmosphere," sug-

gesting that the hospital had modernized

its approach to its clien-

tele.47

On the other hand, the Report advised

that the term "asylum" no

longer be used to describe Loretta

House. Further, the Report re-

vealed how important religion still was.

For the overwhelmingly

Catholic inmates, the hospital provided

"Sunday mass, religious in-

struction, as well as efforts to build

up the religious life at home." Re-

ligion was "stressed as a means of

helping the girls face their future

problems," and their

"spiritual adjustment" was guided by the

chaplain and the Sisters, as well as by

social workers.48 Only the so-

cial worker would have been an

unfamiliar face in 1873.

The Salvation Army Rescue Home

The Salvation Army opened its first

maternity home in the United

States in New York City in 1886,

advertising it as "The Rescue Home

for the fallen and falling . . . for

young women who desire and are

earnestly seeking the salvation of their

bodies and souls."49 This

same philosophy guided the Army's

Cleveland Rescue Home

opened in 1892. Although this home

became Booth Memorial Hospi-

tal, a medical facility specializing in

obstetrics, it retained through

the 1930s the original goal of

reformation and conversion of its fallen

women.

The Salvation Army, founded in 1878 in

England by William

Booth, was an effort to solve through

religion the human problems

created by rapid urbanization. Its

analysis of those problems was in-

dividual and moral rather than political

or social; its solution was the

salvation of the urban dweller through

conversion and "practical

holiness."50 Like the

YMCA which it resembled in its evangelical

thrust, the Army built institutions for

the unfortunate. Unlike the

47. Report filed for Child Caring

Agencies and Institutions by the Division on Chil-

dren, Department of Public Welfare,

State of Ohio, 1935, in Diocesan Archives, 2-7.

48. Ibid., 2, 38-42.

49. Herbert A. Wisbey, Jr., Soldiers

Without Swords: A History of the Salvation

Army in the United States (New York, 1955), 100.

50. Edward H. McKinley, Marching to

Glory: The History of the Salvation Army in

the United States (New York, 1980), 58-59, 34.

130 OHIO HISTORY

YMCA, however, whose intended clientele

tended to be middle-

class and "worthy" of

benevolence, the Army wished to cast a wide

net, working "for the spiritual,

moral and physical reformation of the

working classes; for the reclamation of

the vicious, criminal, disso-

lute, and degraded; for visitation

among the poor and the sick; for

the preaching of the Gospel and the

dissemination of Christian truth

by means of open-air and indoor

meetings.' "51

The Army's sense of fellowship, fostered

by its striking uniforms

and a shared life of austere

missionizing, appealed particularly to

newcomers to cities, cast adrift from

family and community.52 Cleve-

land was a city of such newcomers in

1889 when the Army estab-

lished headquarters there. Cleveland's

population increased forty

percent from 1880 to 1890; more than a

third of this population was

foreign-born.53 With this

growth came ever more visible poverty;

Clevelanders responded with the

establishment of the Charity Or-

ganization Society in 1881 and

Associated Charities in 1884 for the

more efficient distribution of outdoor

relief. The Army's response

was a relief department, shelters for

homeless men, a fresh air camp

for children, and the Rescue Home of

1892.

According to the Home's founder, Colonel

Mary Stillwell, its be-

ginnings were almost accidental. She

and her husband, with their

three children, had been assigned to

gospel work in Cleveland, and

at a meeting in 1892 at which the

scheduled speaker did not appear

and the Army band had played long

enough, Stillwell made an im-

promptu and impassioned request for

funds to house the four home-

less women she had already taken under

her wing. Like Army offi-

cials elsewhere, she was able to enlist

the support of influential

members of the community, and within a

few weeks the Rescue

Home was underway.54 The

Cleveland Plain Dealer wrote approving-

ly of its officers and their work:

"Night after night the devoted wom-

en of the rescue home walk the streets

of the 'red light' district

seeking to save their lost 'sisters.'

Through the vilest slums they pass

unharmed, at any hour of the night.

Their lives seem to be charmed,

as no one, not even the most vicious,

has ever offered to do them

harm. They say they believe that 'God

has given his angels charge

concerning them.' "55 At its

outset, then, the Home, like other Army

51. Ibid., 83.

52. Ibid., 47.

53. Rose, Cleveland, 427.

54. Colonel Mary Stillwell, "The

Origin of Booth Memorial Home and Hospital in

Cleveland, Ohio," unpublished

typescript, unpaged.

55. Cleveland Plain Dealer, clipping,

no date, unpaged.

"Go and Sin No More" 131

institutions, sheltered all comers. This

and the other rescue homes

"were not related primarily to

health care or to unmarried mothers.

The doors were opened to the drug

addict, the homeless, the prosti-

tute, and those referred by the

courts."56

The Rescue Home's first annual report

displayed its primarily evan-

gelical purpose, as well as the

conventional justification for its work:

"Hitherto it has been quite in

order to work for the rescue of fallen

men, and redeemed manhood has been

welcomed into society again

as though he had never been a drunkard

or a debauchee. But very

little effort has been made to save

fallen women, because of the pre-

vailing idea that women seldom if ever

can be reclaimed, and if she is

lifted up, she cannot be trusted, etc.,

etc." The report boasted of

women the home had successfully

rescued-a drunkard, a college

student, an opium addict-and asked

rhetorically, " . . . what minis-

ter or missionary is there who would not

be proud to say they could

lay their hands on as many truly

converted souls as our Rescue offi-

cers can show?"57 In

1904 Rescue administrators claimed that 90

percent of its 2294 inmates that year

had been "reclaimed."58 As in

the YWCA's Retreat, the women were

taught sewing and other do-

mestic skills so that they could earn an

honest living, usually in do-

mestic service, after their dismissal. A

photograph from the Army's

national report of 1900 shows a

"group of girls at work" in the Cleve-

land home, gathered around a table piled

high with unfinished gar-

ments.59

Gradually the rescue homes began to

specialize in the care of

unwed mothers, which brought with it an

emphasis on medical care

and facilities.60 In

Cleveland, for example, the first home became

cramped, and in 1906 a new home was

built on Kinsman Street,

which accomodated 50 women. This

facility included a Maternity

Department, "planned and furnished

with every facility for taking

the very best care of our

patients," as well as a nursery so that

mother and child could be kept together.

The staff included a

56. Karl E. Nelson, "The

Organization and Development of the Health Care System

of the Salvation Army in the United

States of America" (unpublished thesis, 1973,

Brengle Memorial Library, School for

Officers' Training, Suffern, New York), 22.

57. Salvation Army Rescue Home,

Cleveland, Ohio, Annual Report, 1893, 3-10.

58. Salvation Army Rescue Home,

Cleveland, Ohio. Links of Love, Annual Report,

Salvation Army Rescue Work in

Cleveland, 1904, 8.

59. Frederick Booth-Tucker, The

Salvation Army in America, Selected Reports,

1899-1903 (New York, 1972), n.p.

60. Robert Sandall, The History of

the Salvation Army, Vol. III, 1883-1953 (London,

Edinburgh, Paris, Melbourne, Toronto and

New York, 1947-1973), 211-12.

132 OHIO HISTORY

"Christian" physician.61

In that same year a national directory of

Army institutions listed the facility as

the "Cleveland Rescue and

Maternity Home,"62 and

Army publications boasted of the Home's

medical success:

The Maternity Home, of which

unfortunately there are only two in the East,

are most successful.... The one in

Cleveland has a record that is the pride

of the philanthropist doctor who attends. During the

whole nine years of its

being, they have never lost one case

.... Oh, there should be more such

homes.63

Accompanying the professional medical

treatment, however, was

an analysis of illegitimate pregnancy

which combined a secular inter-

pretation with the Army's traditional

religious perspective. The ma-

tron of a Home, asked how the girls

happened to be there, ex-

plained, "Many are betrayed when

they are young and innocent and

then deserted when in trouble."

Many do not have "proper supervi-

sion at home . . . Some fall through

drink." But whatever the case,

they were not "so hard but that the

love of Christ could not save

them."64

Contemporary photographs of the Home's

late Victorian architec-

ture look grim and forbidding, but Army

literature described the

house as "large, airy, and

pleasant, with a lovely, big garden and

wide, roomy porches where the babies can

play and sleep outdoors

all day" and specially designed

furniture in the nursery.65 This em-

phasis on childcare reflected the Home's

membership in the Confer-

ence on Illegitimacy. Like the other

maternity homes, the Rescue

conformed to some of the Conference's

guidelines: for example, im-

plementation of the six-month policy and

the use of a social case

worker. In some ways, however, the

Rescue deviated, again within

the tradition of a broader scope for its

work. Its fees were smaller

than the other homes; it sometimes took

women wih a venereal dis-

ease, and routinely took black women,

the only Cleveland home to

do so.66

61. Salvation Army Rescue Home,

Cleveland, Ohio, Diamonds in the Rough, Annual

Report, Salvation Army Rescue Work in

Cleveland, 1905, 4-5.

62. Review of the Women's and

Children's Rescue Work During 1906 (New York, no

date), n.p.

63. Where the Shadows Lengthen: A

Sketch of the Salvation Army's Work in the Unit-

ed States of America (New York, 1907), 19.

64. Ibid., 20.

65. Neighbors: A Story briefly told

of the labor of love and interesting events in the

lives of The Salvation Army Women

Social Officers (New York, 1911),

25-26.

66. FCP, Conference on Illegitimacy,

December 1, 1913, Container 30, Folder 738;

March 30, 1921; January 9, 1922,

Container 30, Folder 739.

"Go and Sin No More" 133

The trend toward a dual rescue home and

maternity hospital con-

tinued on a national scale; by 1920 the

Army managed similar institu-

tions in New York, Detroit, Boston, and

Greenville, South Carolina.

The rescue work continued, particularly

during the social disloca-

tions caused by World War I, for women

who were not pregnant, but

cast adrift in the cities as prostitutes

or derelicts.67 Throughout the

1920s, however, the term "Rescue

Home" was replaced generally by

"Home and Hospital for Unmarried

Mothers," and these became

known as "Booth Memorials" as

in Cleveland, and specialized in the

medical care of unmarried mothers.68

The reformatory goal was not lost,

however, as the hospitals

stressed religion, discipline, and

domestic skills, and an obligatory

confinement period.69 Army

work with unwed mothers continued to

be carried on with "deep religious

earnestness."70 The numbers of

these women dwindled at Booth during the

1930s, as at the other

maternity facilities, and in 1933 Booth

began to take private, married

patients, who would eventually

constitute most of its clientele.

The Mary B. Talbert Home

Booth Memorial's origins lie in the

demographic upheaval caused

by the immigration into the city of

whites from Europe and the

American countryside. The beginnings of

the Army's second Cleve-

land home for unwed mothers, the Mary B.

Talbert Home, lie in the

"great migration" of Southern

blacks into Cleveland in the late 1910s

and the early 1920s. Growing numbers of

the city's unwed mothers

were black, but only the Rescue Home

accepted them, and then

only four or five.71 By 1924 the

once-Jewish neighborhood on Kins-

man Street, site of the Rescue Home, was

becoming black, and the

Army increased the numbers of black

women it took.72 The Confer-

ence on Illegitimacy then suggested that

the Army run a separate fa-

cility for black women, as the Army did

in Cincinnati. The Confer-

ence's rationale revealed its thinking

on both blacks and on unwed

67. War Service Herald and Social

News, May, 1920, 4-5.

68. Handbook of Information, Homes

and Hospitals for Unmarried Mothers (New

York, no date), 13-14.

69. McKinley, Marching, 139.

70. Ethel Verry, "Meeting the

Challenge of Today's Needs in Working with Unmar-

ried Mothers," Paper given at the

War Regional Meeting of the National Conference of

Social Workers, 1943, n.p.

71. FCP, Conference on Illegitimacy,

January 9, 1922, Container 30, Folder 739.

72. Ibid., June 21, 1924.

|

134 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

mothers. Far fewer black than white women delivered children in maternity homes even though the black women, the Conference felt, were more in need of the special "training" that such homes provid- ed. The Conference also believed it inadvisable for black and white women to be housed in the same facility.73 Therefore, with the urging of the Welfare Federation and financial support from the Cleveland Council of Colored Women, the Army opened the Mary B. Talbert Home. When the Army moved its facility for white women to East Cleve- land, the Mary B. Talbert moved to the old Kinsman location. The regimen for black women included religious training as it did for white women at Booth, but the vocational training assumed, proba- bly quite correctly, that the black women would find jobs only as do- mestics; "plain sewing, cooking, and general housework" were the only subjects taught.74 The Mary B. Talbert Home also served Cleveland's black medical community, providing medical students with practice in obstetrics and doctors with a place to deliver their private patients since most of

73. Ibid. 74. Ibid., December 14, 1925. |

"Go and Sin No More" 135

Cleveland's hospitals did not allow

blacks to practice there.75 Black

unwed mothers continued to receive

special counseling and religious

guidance at the Mary B. Talbert until

1961 when it was merged with

Booth.

The Maternity Home

MacDonald House of University Hospitals

is the only one of the

maternity facilities to have begun

primarily as a medical institution for

the training of obstetric

practitioners-nurses and doctors. However,

because of the necessity of treating

poor and unwed mothers, the

Hospital acted also as a benevolent and

social service institution in

some ways like the maternity homes.

Seventeenth and eighteenth century

hospitals were designed pri-

marily for the indigent who had no homes

where they could be

cared for. Hospitals, therefore, were

associated with poverty and the

high mortality rates which accompanied

the medical treatment of

the indigent in inadequate facilities by

inadequate practitioners. Like

other institutions for the poor,

hospitals became the focus of private

benevolence, funded by male

philanthropists and managed by

boards of local women who saw to the

daily needs of the hospital

and its patients.

Maternity or lying-in hospitals followed

this pattern. Through the

nineteenth century, they were used

almost exclusively by poor and

often unmarried mothers, and the

hospitals sought to provide not

only for the physical health of these

patients but for their "moral re-

habilitation," attempting to

"treat the whole woman; body, behav-

ior, and belief."76

Although these benevolent impulses

lingered through the 1930s,

hospitals also provided training

facilities for the medical profession.

Until the twentieth century most doctors

received their training on

the job-that is, on the patients-rather

than in the medical school

classroom. Obviously, it was more

convenient to practice on patients

gathered together in one place such as a

hospital than to search out

individuals. Further, since patients

were generally poor, a profession-

al error made less difference.

By the nineteenth century, it was

particularly difficult for a male

doctor to acquire training in

obstetrics. The field had been monopo-

75. Letter from Commissioner Edward

Carey to Miss Eleanor Custer, May 2, 1983.

76. Richard W. Wertz and Dorothy C.

Wertz, Lying-In: A History of Childbirth in

America (New York, 1977), 186-89.

136 OHIO HISTORY

lized by midwives since the colonial

period. Although male mid-

wives and general practitioners began to

deliver babies by the sec-

ond half of the eighteenth century,

developing notions about female

modesty made gynecological examinations

and child deliveries med-

ically and culturally difficult for men

to perform. As a result, many

doctors began their practices without

ever having seen a delivery, let

alone having performed one.77 As

the medical profession became in-

creasingly self-conscious about its

professional standards in the first

half of the nineteenth century, this

ignorance became less accep-

table. Lying-in or maternity hospitals

were a good way to provide

fledgling obstetricians with some actual

practice.

MacDonald House owed its establishment

to this need to provide

training for Cleveland's growing medical

profession, as well as to the

secondary benevolent desire to reform

unmarried mothers. In 1891 a

group of philanthropic Clevelanders

founded the Maternity Home.

Its object was to "furnish a home

for worthy women during confine-

ment and the lying-in period and to

educate nurses in the specialty of

obstetrics . . . and to furnish

maternity cases for the C.H.H. [Cleve-

land Homeopathic Hospital]

College."78 The affiliation with the

homeopathic rather than the

"regular" or orthodox medical estab-

lishment is not surprising since many

prominent and wealthy Cleve-

landers, including John D. Rockefeller,

were followers of homeopa-

thy. Homeopathy, which relied on minute

doses of drugs which

induced in the patient reactions like

the symptoms of his disease,

was a well-respected therapy until the

American Medical Association

drove homeopaths almost out of the

profession in the early twentieth

century.79

Rules for the Maternity Home appear

stringent by today's

standards. A patient, apparently

regardless of her health, could be

dismissed by the head matron for

disobedience.80 But rules for all

hospital patients were strict, perhaps

because most patients were un-

familiar with hospitals and perhaps

because patients were most often

poor and, therefore, considered

naturally disorderly. The house

rules for the wards of Cleveland's

Lakeside Hospital in 1898, for ex-

ample, forbade patients from using

"profane or indecent language"

77. Frederick W. Waite, Western

Reserve University Centennial History of the School

of Medicine (Cleveland, 1946), 77.

78. By-Laws of Maternity Home of

Cleveland, 1891, 1, in Archives of University

Hospitals, Cleveland, Ohio.

79. James G. Burrow, Organized

Medicine in the Progressive Era: The Move Toward

Monopoly (Baltimore and London, 1977), 71-82.

80. By-Laws of Maternity Home, 15-16.

"Go and Sin No More" 137

and making "immoral or infidel

statements," playing cards, smoking

tobacco, or drinking alcoholic

beverages.81 Yet despite the rigidity

of hospital rules in general and

references to "worthy women" aside,

there are indications that the first

patients at the Maternity Home

were indeed unwed mothers. The Matron,

for example, was required

to "exert a religious influence

over the inmates and hold some reli-

gious service each day,"82 suggesting

the conventional belief that re-

ligious conversion would reclaim a

woman's lost virtue. In addition,

funds for the Home were raised in 1893

by a series of public perform-

ances of "marriage dramas,"

which included an ancient Greek mar-

riage, a "Jewish ritual," and

the wedding of Pocahantas and John

Rolfe.83 The moral seems

obvious. And in fact, the Home claimed to

have "received and cared for more

than two hundred unfortunate

women and girls, mostly delivered of

illegitimate children" by

1896.84

Until the turn of the century, the

institution retained its ties to the

Cleveland Homeopathic Medical College.

The College's annual an-

nouncement for 1897-98 boasted that

"The Maternity Home fur-

nishes a class of clinical cases of the

greatest utility to those about to

enter the general practice of medicine.

Each member of the senior

class will have an opportunity to

witness a variety of demonstrations;

will be taught the manipulation of

instruments and all kinds of obstet-

rical appliances and will be required

personally to conduct at least

one case of labor under the supervision

of a clinician."85

Shortly after this, however, the

Maternity Home changed its affili-

ation and, to some extent, its focus as

well. It is listed in the 1901 city

directory as "The Maternity

Hospital" rather than "Home,"86 em-

phasizing the medical over the

benevolent orientation. By 1905 "reg-

ular" physicians, as well as

homeopaths, appeared on its Board.87

Of particular significance was the

presence on the Board of Dr. Ar-

thur Bill, who in 1907 began his own

out-patient obstetrical service.

On his staff were students from the

Western Reserve University

81. Thirty-Second Annual Report of

the Lakeside Hospital, Cleveland, Ohio, 1898,

85-86.

82. By-Laws of Maternity Home, 15.

83. Promotional materials in Vertical

file, Maternity Home, Cleveland, Ohio, West-

ern Reserve Historical Society.

84. Cleveland, Ohio, Centennial

Commission, The History of the Charities of Cleve-

land, 1796-1896 (Cleveland, 1896), 52.

85. The Cleveland Homeopathic Medical

College, Annual Announcement, 1897-98,

25.

86. Cleveland Directory for 1901 (Cleveland,

1901), 1683.

87. The Maternity Hospital, Annual

Report, 1905-1906, n.p.

138 OHIO HISTORY

School of Medicine. In 1913 the Hospital

became the headquarters

for this service. The Hospital enlarged

its facilities to care for its

growing clientele, and in 1914 the staff

included ten visiting doctors,

one resident physician, and 20 student

nurses.88

At the same time, there was growing

dissatisfaction at the Medical

School with training provided almost

exclusively by out-patient de-

liveries,89 and therefore,

the Hospital became formally affiliated

with the Western Reserve University

Medical School in 1917,90 es-

tablishing itself solidly as a

"regular" training institution and, in-

creasingly, as a place for respectable

married women to have babies.

Plans to move the Maternity Hospital

(and Babies and Children's

Dispensary, a separate institution) to

the site of University Hospitals

was delayed by World War I, but effected

in 1925.91 In 1936 the

Hospital was re-christened MacDonald

House after Calvina Mac-

Donald, its head nurse from 1913 to

1933, who was particularly influ-

ential in shaping its training programs

for obstetrical nurses.

The Hospital's medical focus was clearly

stated: its object was "to

provide facilities for the hospital care

and home care of maternity

cases and for the advancement of

obstetrical education and to main-

tain dispensaries for prenatal and

medical care for mothers."92 Yet

the Hospital could not disengage itself

entirely from its initial reform-

ist goals. Although it proudly noted its

paying patients, its annual re-

port of 1908 admitted that its clientele

also included "more than one

deserted wife with a babe in her

arms," for whom the hospital's re-

lief committee found a home, board, and

a job.93 This committee,

staffed by volunteers, soon became the

Social Service Department

with a medical case worker.

The Hospital also was a member of the

Federation for Charity and

Philanthropy and had a seat on the

Conference on Illegitimacy, with

which it shared some, but not all, goals

and techniques for the treat-

ment of unmarried mothers. For example,

the Hospital had a policy

of not taking "second

offenders" although, like other institutions, in

actual practice it sometimes did.94

On the other hand, the Hospital

88. "Facts about 18 Cleveland

Hospitals Represented in the Hospital Council,"

(Cleveland, 1914), n.p.

89. Forty-Seventh Annual Report of

the Trustees of the Lakeside Hospital (Cleveland,

1913), 58.

90. Waite, Western Reserve, 253.

91. Ibid., 254.

92. Maternity Hospital and Dispensaries

of Maternity Hospital and Western Reserve

University, Annual Report, 1924,

29.

93. Maternity Hospital, Cleveland, Ohio,

Annual Report, 1909, 17.

94. FCP, Council on Illegitimacy, March

12, 1923, Container 30, Folder 739.

"Go and Sin No More" 139

did not provide "long-term care and

training of unmarried mothers"

as did the other facilities. As a

Hospital representative explained in

1924, "the suggestion of caring for

unmarried mothers at the hospital

comes from the desire to teach nurses

and doctors." Furthermore,

the Hospital was so much more expensive

than the other maternity

facilities ($4.10 a day for mother and

infant as opposed to $.85 in the

homes) that the Hospital could not

afford to keep its patients long

enough to "train" them, nor

could the patients have afforded to stay

if they had wanted to.95 The

Hospital did, however, refer its unwed

mothers to other welfare agencies such

as the Humane Society.96

The Hospital also worked closely with

the maternity homes, some-

times supervising there the deliveries

of women given prenatal care at

the Hospital out-patient clinics.97

Annual reports through the 1920s

record the increasing number of unwed

mothers treated at the Hos-

pital or its clinics; more and more of

these were black.98

The numbers of all women treated had

swelled from 49 in 1893, to

368 after the Hospital's affiliation

with Dr. Bill, to 1375 in 1923,99 re-

vealing the growing acceptability of

hospital care to middle-class

women. By 1936, however, the number of

unmarried mothers at

MacDonald House was half what it had

been in 1929.100 The ex-

pense of its specialized facilities had

put it beyond the reach of those

women whom it had been founded to serve.

The Florence Crittenton Home

When the Florence Crittenton Home was

founded in Cleveland in

1912, it was part of a chain of seventy

Crittenton Homes across the

country and abroad.101 The chain was

begun in 1883 by Charles

Crittenton, the "millionaire

evangelist," a millionaire by virtue of his

flourishing pharmaceutical business and

an evangelist by avocation.

In his work with a New York City

mission, Crittenton visited dives

95. Ibid., June 21, 1924.

96. Ibid., March 31, 1921.

97. First Annual Report of the

University Hospitals of Clevelandfor 1927 (Cleveland,

1928), 74.

98. Annual Report of the University

Hospitals of Cleveland for 1928 (Cleveland,

1929), 234.

99. Maternity Hospitals and Dispensaries

of Maternity Hospital and Western Reserve

University, Annual Report, 1923,

3.

100. FCP, Children's Council, Committee

on Unmarried Mothers, August 14, 1936,

Container 33, Folder 829.

101. Katherine G. Aiken, "The

National Florence Crittenton Mission, 1883-1925: A

Case Study in Progressive Reform"

(Ph.D. dissertation, Washington State University,

1980), 85.

140 OHIO HISTORY

and brothels and, according to his own

account, realized one night

when he had advised an unfortunate woman

to "Go and sin no

more" that she had nowhere to go;102 hence, the founding of the

first Florence Night Mission, named

after Crittenton's dead daugh-

ter. The Mission offered food, shelter,

and gospel services to home-

less women and prostitutes, sought out

by a rescue band of Christian

workers inspired by Crittenton's message

of salvation.103 Within fif-

teen years, the Mission had become the

National Florence Crittenton

Mission, chartered by the federal

government. By 1933 there were 65

Crittenton Homes with an annual budget

of $700,000 to $800,000.104

Over these years also there were perceptible

shifts in focus and em-

phasis, from the reformation of the

prostitute through religious con-

version to homes for unwed mothers, from

"the more fervidly emo-

tional spirit of the earlier

evangelistic years to a thorough and careful

study of every phase of the problem of

helping girls."105 Yet despite

these changes, the Florence Crittenton

Home, in Cleveland anyway,

retained through the 1930s much of the

flavor of the original evangel-

ical rescue work.

Cleveland's Home was founded relatively

late, perhaps because

the city already had three

well-established homes as well as hospi-

tals which treated unwed mothers. Even

so, neighbors twice

blocked the Home's attempt to buy

property.106 Once underway,

the Home bore clearly the impress of the

then-president of the Na-

tional Florence Crittenton Mission, Dr.

Kate Waller Barrett, who suc-

ceeded Crittenton after his death and

whose meeting in 1910 with a

Cleveland social worker inspired the

Home's establishment.107

Barrett was not only an administrator

but a philosopher on the

treatment of unwed motherhood. In Some

Practical Suggestions on

the Conduct of a Rescue Home, Barrett described the ideal home as

a "big, old-fashioned, roomy house

in a quiet part of the city, with

large, sunny, bright rooms for sitting

rooms and workrooms, with

books and magazines on hygiene, child

study and self-culture" and

an especially pretty room for the

nursery, "for no home is complete

without a baby."108 Contemporary

photographs of the first home on

102. Otto Wilson, Fifty Years' Work

with Girls, 1883-1933 (Alexandria, Virginia,

1933), 30.

103. Aiken, "National Florence

Crittenton," 15-24.

104. Wilson, Fifty Years, 4-5.

105. Ibid., 7-8.

106. Ibid., 254.

107. Ibid., 253.

108. Kate Waller Barrett, M.D., Some

Practical Suggestions on the Conduct of a Res-

cue Home (New York, 1974), 7-9.

|

"Go and Sin No More" 141 |

|

|

|

Eddy Road suggest such a physical setting.109 Crittenton Homes were to be "true homes-God's homes" but also places of discipline and order. All girls helped with the domestic chores: "We believe that every lady should know how to cook, wash, and iron, if she does not know anything else, and as we expect our girls to be ladies in the highest and truest sense, they must all learn to do these things, and do them well."110 As at the Retreat, which this Home most closely resembled, "spiritual regeneration and industrial inde- pendence" were to be "the key-note of all our endeavors toward the upbuilding of character."111 Barrett regarded pregnancy out of wedlock as a "sin" and spoke of reformation through "the Holy Ghost."112 She became best known, however, among social welfare workers who dealt with un- wed mothers for her belief in motherhood itself as a means of spiri- tual regeneration. She was a vocal advocate of the six-month or long- er confinement during which the mother nursed her child: "There is a God-implanted instinct of motherhood that needs only to be

109. Scrapbooks in Florence Crittenton Home Papers, MS. 3910, Western Reserve Historical Society, Container 2, Folders 10 and 11 (hereinafter referred to as FCH Pa- pers). 110. Barrett, Practical Suggestions, 15, 26. 111. Ibid., 110. 112. Ibid., 100. |

142 OHIO HISTORY

aroused to be one of the strongest

incentives to right living,"113 Bar-

rett maintained. She shared this belief

in the special virtue of moth-

erhood with other women reformers of the

period, from settlement

house workers to suffragists.

The Cleveland Home almost immediately

became a member of the

Federation for Charity and Philanthropy

and the Conference on Ille-

gitimacy. The Federation was called upon

several times in the

Home's early years to bail it out

financially although it also received

funds from the National Florence

Crittenton Mission.114 In return, of

course, the Federation imposed controls

upon the Home, insisting

upon intelligence testing and screening

for venereal disease of its cli-

entele and the use of a social worker.

Yet despite the inevitable

standardization, the Cleveland Home

came close to capturing the letter, and

perhaps the spirit, of Barrett's

injunctions, possibly because the Home

was small, sheltering from

ten to fifteen girls most of the time.

The girls received religious in-

struction and had Bibles in their rooms;

prayers were part of the dai-

ly routines, just as they were of the

Board of Managers' meetings.115

The Home received funds, as well as

gifts in kind, from local Critten-

ton "Circles," usually

affiliated with a Protestant church. Inmates at-

tended classes in arithmetic, English

and domestic science in the

Home.116 To create a home-like

atmosphere, its Board of Managers,

volunteers from the neighboring

communities, planned birthday par-

ties and holiday festivities for the

girls, which they attended them-

selves. Managers also taught some of the

classes and acted as "big

sisters" for the inmates after they

left the Home.117

Numbers of babies born and sheltered

were always carefully and

proudly recorded every year, but the

Home in its first decade shel-

tered more than unwed mothers. In 1916,

for example, some girls

had been referred to the Home from the

Human Society, some from

Juvenile and Municipal Courts, and some

from Associated Charities;

these were women whose problems were

probably delinquency or

poverty rather than illegitimate

pregnancy. And the thrust, in the

spirit of Charles Crittenton, was broad

and evangelical. "Rescue

work is peculiar-but not popular,"

explained the Home's annual re-

113. Ibid., 47.

114. FCH Papers, Board of Trustees

minutes, December 15, 1913, Container 1, Fold-

er 2.

115. Ibid., Board of Managers

minutes, May 5, 1914, Container 1, Folder 11.

116. Ibid., July, 1918, Container

1, Folder 12.

117. Ibid., April 1, 1913;

September 3, 1913; September 14, 1915, Container 1, Folder

11.

"Go and Sin No More" 143

port. "No girl is turned from our

door. We care for any woman in need

of help, regardless of race or

creed." (In actual fact, the Home did

not take black women.) "While

social service work and religious

work differ, yet religion is at the

heart of life as well as the basis of so-

cial advancement, and without it our

attempt at this work would

prove a failure. The more we trust in a

Higher Power for supreme

help, and lean entirely upon Him for

strength and guidance, the more

we will be able to accomplish. If we

clothe and shelter and feed our

girls and do not give them Bread of

Life, our work will be in

vain."118

The religious flavor is unmistakable,

but the Crittenton Homes did

not rely entirely upon God. Each had a

legal committee which

sought to establish and maintain the

legal rights of the mother and

child, particularly its right to

financial support from the father.119

Crittenton staff sometimes tried to

track down the putative father

to bring him to justice or induce him to

marry the mother of his

child. 120

Not until the 1920s did the Home become

primarily a maternity fa-

cility, although its focus was still not

on medical care: "Ours is not a

commercialized maternity hospital, but a

place where an unmarried

girl is welcome, who, unfortunately, is

pregnant, and has nowhere

else to go for the care and privacy she

otherwise could not afford." A

girl was urged to stay in the Home for

prenatal care and medical at-

tention during childbirth, but more

important, "with us she is sur-

rounded by influences which will help to

strengthen her character,

the weakness of which resulted in her

needing our help." Hence, the

Home retained the six-month policy

although this began to weaken

during this decade.121 The frontispiece of the 1929 brochure bore

the motto which harked back to

Crittenton's original impulse: "Go

and sin no more.' "122

The reformatory goal of the Home was

reflected in its restrictive

policies, which prevented girls from

leaving the premises unless ac-

companied by Board members, who did take

the girls on summer

outings and held teas and parties for

them.123 Best known was the

annual June Day, a lawn party and bazaar

attended by local friends

of the home and sometimes by former

inmates. Board members seem

118. Florence Crittenton Home, Brochure,

1916-1917, 11-14.

119. Ibid., 14.

120. FCP Conference on Illegitimacy,

January 27, 1916, Container 30, Folder 738.

121. Florence Crittenton Home, Brochure,

1926, n.p.

122. Ibid., 1929, n.p.

123. Wilson, Fifty Years, 256.

|

144 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

to have shouldered much of the maintenance and administrative re- sponsibilities since the only paid resident staff was the matron; a pe- diatrician and obstetricians were on call. The Home's small size and the intimate contact with interested volunteers may explain the fond letters and birth and wedding announcements sent by former in- mates which were kept in the Home scrapbooks.124 The Home barely held its own through the Depression years, its numbers remaining about constant.125 Its link with the other Flor- ence Crittenton Homes from which it drew clientele and where it could place local girls gave it some advantage over the other materni- ty homes. The Cleveland Home remained a maternity facility until 1970. In 1973, as a member of the Child Welfare League of America, Florence Crittenton Services opened two homes for delinquent but non-pregnant girls. The serious decline in numbers of unwed mothers, noted at all the facilities by the mid-1930s, had several explanations, more obvious to us today perhaps than to the facilities themselves at the time. First, the Depression cut private funding to the institutions; county relief funds did not pay for confinements in maternity homes ei- ther.126 The homes traditionally had not charged patients who

124. FCH Papers, Container 2, Folders 10 and 11. 125. FCP, Children's Council, Committee on Unmarried Mothers, November 30, 1936, Container 30, Folder 829. 126. Ibid., May 4, 1936. |

"Go and Sin No More" 145

could not pay, but a woman might have

preferred to have a baby

inexpensively at the City Hospital than

to become a charity patient at

a maternity home. Unmarried mothers also

seemed less ashamed to

have their babies in their family

homes,127 thus reversing the trend

toward hospital deliveries. Last, the

birthrate for both legitimate

and illegitimate children dropped.

With the Retreat and the Florence

Crittenton Home in danger of

folding, therefore, Cleveland maternity

homes used the Conference

on Illegitimacy meetings to do some

needed soul-searching and re-

evaluation. At several meetings,

Conference representatives suggested

that the homes did not offer enough

options to their clientele. In

1934, for example, the Conference

recommended more vocational ed-

ucation, more recreation facilities, and

more emphasis on assimilating

the unmarried mother into the

community.128 The six-month con-

finement policy was also being modified

in some of the homes, per-

haps out of economic necessity. 129 A committee on

illegitimacy of the