Ohio History Journal

JAMES N. GIGLIO

The Political Career of

Harry M. Daugherty, 1889-1919

Historians have written about Harry

Micajah Daugherty only within the context

of the Warren G. Harding era. His

association with the 1920 campaign and the

Harding presidency has received

extensive coverage. Works on the 1920's have

amply covered his involvement in the

administration scandals. Daugherty's pre-

1912 career, however, has been virtually

ignored; only a scant outline of early

political adventures has come from the

writings of Harding scholars.1 No criticism

is intended. The fact is, their focus is

on Harding and he was not aligned with

Daugherty until 1912. By that time,

Daugherty's political career had already under-

gone thirty years of ups and downs.

Scandal, overambition, and some bad luck

had incurred him enough opposition

within the party to prevent his ever gaining

election for any important elective

office. He managed to hang on as a factional

leader-one who had as many enemies as

friends. This article seeks to explore

Daugherty's political setbacks and how

he overcame them to become Harding's

presidential campaign manager in 1919.

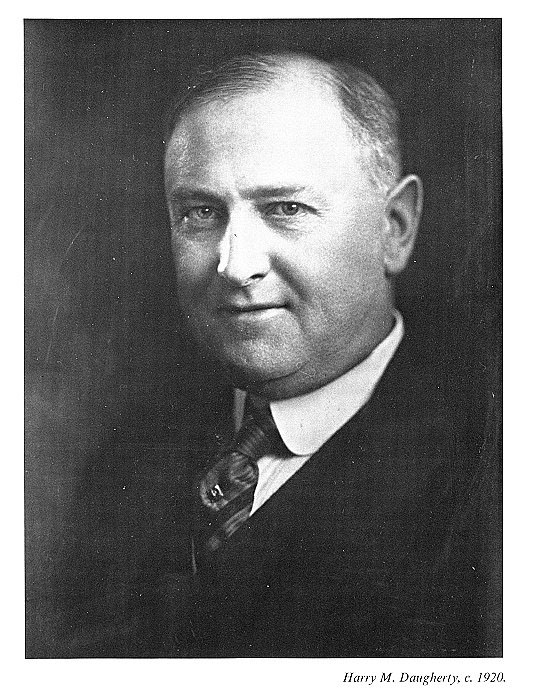

In 1889 Daugherty won his first state

office. Rural Fayette County, some thirty

miles southwest of Columbus, elected the

twenty-nine year old lawyer from Wash-

ington Court House to the Ohio House of

Representatives. The Cyclone and Fay-

ette Republican had assured the local farmers and businessman

"that their interests

will be well subserved . . ."

because "there is no more levelheaded or industrious

gentleman in Fayette county than Mr.

Daugherty."2 The thin and mustachioed

legislator intended to repay such

accolades. He sponsored several bills that were

beneficial to his constituency; he also

became an excellent organizer and speaker

and an expert on parliamentary law. On

several occasions he ably occupied the

speaker's chair. For that reason he was

considered a possible choice as speaker

of the house in the event the

Republicans regained a legislative majority in the

fall election of 1891. The Republican

state convention of 1890 further enhanced

Daugherty's reputation as a coming

political figure. Not only was he named chair-

1. See Andrew Sinclair, The Available Man: The Life Behind

the Masks of Warren Gamaliel Harding

(New York, 1965), 37-38; Francis

Russell, The Shadow of Blooming Grove: Warren G. Harding in His

Times (New York, 1968), 108-112; Robert K. Murray, The

Harding Era: Warren G. Harding and His

Administration (Minneapolis, 1969), 18-19; and Mark Sullivan, The

Twenties (Our Times, 1900-1925, VI,

New York, 1935), 19-22.

2. Cyclone and Fayette Republican (Washington

Court House), August 7, 1889.

Mr. Giglio is assistant professor of

history at Southwest Missouri State College, Springfield.

|

|

|

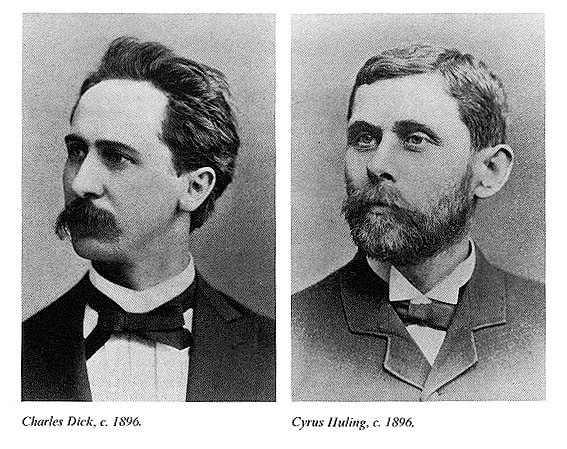

Harry M. Daughtery, c. 1900. man of his county delegation, but convention delegates selected him for the state central committee as a representative of the tenth state congressional district.3 This gave Daugherty some influence in formulating party policies in Ohio. All in all, his first term represented an enviable record of political accomplishment. Factionalism within the Ohio Republican party in the summer and fall of 1891, however, complicated Daugherty's reelection bid. He eventually found himself caught up in the feud between Senator John Sherman and ex-Governor Joseph B. Foraker, the leading Republicans of the state. Their organizations had fought each other intermittently since the 1888 Republican national convention where Foraker deserted the presidential-seeking Senator for the candidacy of James G. Blaine. After that incident, the intraparty battles were over the perennial issue: who would control state politics-Sherman or Foraker?4 The fight intensified in 1891 because of Foraker's desire to unseat Sherman in 3. Ibid., April 30, July 16, 30, 1890; April 30, 1891. 4. Everett Walters, Joseph Benson Foraker: An Uncompromising Republican (Columbus, 1948), 62- 103. Russell suggests that there were also strong ideological differences separating the two antagonists. Russell, Shadow of Blooming Grove, 115-116. |

154 OHIO

HISTORY

the January 1892 senatorial contest.

Since Ohio Senators were then elected by the

General Assembly, Foraker needed not

only a Republican legislature, but also

one that had a majority of Foraker

supporters in order to win. Consequently, he

sought the support of Republican

assemblymen like Daugherty. Related to the

Forakers through marriage, Daugherty was

sympathetic to the ex-governor's sena-

torial ambitions. He had managed to

champion Foraker in the past without alien-

ating Sherman supporters in his county.

Local political conditions, however, now

put him on the fence. Republican leaders

in Fayette County who were over-

whelmingly for John Sherman tried to pressure Daugherty

to commit himself to

the Senator's candidacy. Joseph G. Gest,

editor and business manager of the Cyc-

lone and Fayette Republican, published an article in the Cincinnati Enquirer on

August 1, declaring that Daugherty

"will be unceremoniously shelved" as represen-

tative unless he ended his neutrality.5

Immediately upon reading Gest's article,

Foraker wrote Daugherty that he did not

want to embarrass him. Explaining that

he would rather lose the support of his

friends than have them suffer defeat on his

account, he nevertheless told Daugherty

that he needed his vote. He then called

the Sherman forces cutthroats who had

knifed him in 1889 and would do so again

if he were now nominated as senator.6

Daugherty replied that the "Sherman men

are many and active here" in the

county. He indicated that the pro-Sherman Gest

and Thomas Marchant of Fayette were

attempting to obtain his pledge to Sher-

man for a guarantee that he would be

renominated and then reelected to the Gen-

eral Assembly that Novenber.7

In spite of these threats, Daugherty's

renomination was unopposed at the Fayette

County Republican convention in

mid-August. The convention also endorsed the

candidacy of Sherman. After Daugherty's

nomination, the party leaders appointed

three delegates to escort him into the

convention hall where he delivered a short

address in which he pledged that if

reelected he would work in the interest of his

constituency and would "support the

candidate for United States Senator who may

be the choice of the Republicans of

Fayette county."8 That evening Daugherty as-

sured Foraker's campaign manager,

Charles J. Kurtz, of his allegiance to Foraker.9

In the ensuing weeks, Daugherty stumped

Fayette for his own candidacy, while

Foraker campaigned in behalf of the

state ticket. They did not see each other until

October 31, three days before the state

elections. At that meeting, Foraker asked

Daugherty if it were permissible for the

Cincinnati Commerical Gazette, which was

publishing senatorial preferences, to

indicate that he was for Foraker. As Foraker

wrote Kurtz the following day, Daugherty

"at once hemmed and hawed, and

said that was a matter he ought to keep

quiet about for the present." Foraker then

asked Daugherty whether he had made any

pledges to the Sherman people. Daugh-

erty replied that he had not, that he

would be all right when the time came but

that he had a difficult county to handle

and was much embarrassed by the situa-

tion there. Foraker then spoke frankly.

Realizing that the Sherman forces had

5. Cincinnati Enquirer, August 1,

1891.

6. Joseph Benson Foraker to Harry M.

Daugherty, August 1, 1891, Box 27, Joseph Benson Foraker

Papers, Cincinnati Historical Society.

7. Daugherty to Foraker, August 3, 1891,

Box 32, ibid.

8. Cyclone and Fayette Republican, August

20, 1891. Daugherty told a local political leader at the

convention that he would not only

support Sherman's reelection in the General Assembly but would

also back his renomination in the party

caucus. Hills Gardner to John Sherman, December 15, 1891,

John Sherman Papers, Vol. 561, Library

of Congress.

9. James M. Cox, Journey Through My

Years (New York, 1946), 303-304.

|

|

|

probably already promised to provide for Daugherty in the organization of the legislature in January, he told the Fayette representative that "we had not for- gotten him in considering these matters; that on the contrary, we had kept him in mind, with a view to making for him a suitable and satisfactory provision." Foraker further related to Kurtz that Daugherty "may be alright, but my con- fidence in him is not very strong."10 In the November election Harry Daugherty was swept into the General Assembly for another two-year term. William McKinley was elected governor, and the Re- publicans captured the Ohio legislature by nearly a two-thirds margin, insuring the election of a Republican to the Senate that January when the legislature again convened. Based upon the composition of the legislature, Foraker appeared to have the initial advantage in the senatorial contest. Two days after the election, he claimed a majority of eleven over Sherman.11 Sherman's friends took Foraker more seriously after the election. Campaign 10. Foraker to Charles Kurtz, November 1, 1891, uncatalogued Charles Kurtz Papers, Ohio His- torical Society. 11. Walters, Foraker, 101. |

|

|

|

manager Mark Hanna raised thousands of dollars in Sherman's behalf. The pro- Sherman William Hahn, the Republican state executive committee chairman, put the money to good use. Agents were selected to enter doubtful districts to bring local public pressure to bear against Foraker-leaning legislators. State committee- man J. C. Donaldson was given $10,000 to direct the canvass.12 Daugherty remained one of Sherman's prime targets, for his name often appeared on published lists as a Foraker supporter in the post-election period.13 The Senator's lieutenants worked in conjunction with the Cyclone and Fayette Republican to pressure Daugherty to declare for the incumbent. The newspaper reminded him of county's overwhelm- ing support of Sherman and predicted his reelection by a large majority.14 Leading Fayette Republicans also cooperated with Sherman leaders in an effort to bring Daugherty into line. They conducted a canvass to overwhelm him with the senti- ment of county Republicans.15 12. Herbert Croly, Marcus Alonzo Hanna: His Life and Work (New York, 1912), 160-161. 13. Cincinnati Enquirer, November 14, 1891. See also Cyclone and Fayette Republican, November 12, 1891. 14. Ibid., December 24, 1891. 15. Gardner to Sherman, January 19, 1892, Vol. 568, Sherman Papers. |

Harry M. Daugherty 157

In the face of increased pressure,

Daugherty's vote still remained uncertain.

Privately sympathetic to Foraker, he

failed to reaffirm his August pledge to support

"the choice of the Republicans of

Fayette County," which happened to be John

Sherman. Foraker, however, was beginning

to lose patience with Daugherty. He

confided to Kurtz that Daugherty

neglected to answer his correspondence and

that he saw other signs he did not

like.16 Foraker's suspicions turned out to be

correct. On December 11 Hahn arranged to

have Daugherty visit Sherman in

Washington, D.C. He assured the Senator

that Daugherty would travel on an eve-

ning train so that "no one would

know anything about him being there." He also

predicted Daugherty's vote for Sherman.

In almost the same breath, he warned

Sherman that it would "require

considerable money to carry on our work," although

"nothing will be done at these

headquarters that will in anyway compromise your

personal honor."17 No

record exists as to what transpired in Daugherty's consulta-

tions with Hahn and Sherman. He most

likely, however, assured them that he would

honor his August pledge and signed a

statement to that effect.18

Daugherty finally arrived in Columbus on

December 29, four days before the

speakership and nine days before the

senatorial contests. That evening he went to

Foraker's hotel room to tell him that

sentiment for Senator Sherman was so strong

in Fayette County that he would have to

vote accordingly. He then showed Foraker

the "card" in which he had

made his Sherman declaration. Foraker requested

Daugherty to delay making his

announcement in the county papers until the day

before the senatorial caucus.19

In the party caucus on January 2, 1892,

Lewis C. Laylin, Sherman's candidate

for speaker of the house, defeated John

F. McGrew, Foraker's choice, by four

votes. Much to Sherman's concern,

Daugherty voted as pledged for McGrew, a

close friend who resided in nearby Clark

County. This preliminary setback placed

Foraker at a disadvantage for the

senatorial contest to be held on January 6.

As promised, Daugherty publicly

reaffirmed his pledge to Sherman the day

before the senatorial contest, and on

the following day presided over the caucus.

After his opening remarks, a debate

ensued among the delegates on whether to

use an open or secret ballot to nominate

a senatorial candidate. Foraker favored

a secret vote because he had more to

gain in not forcing legislators to stand by

their pledges. He perhaps reasoned that

Daugherty, among others who had favored

a secret ballot, could then dishonor his

pledge to vote for Sherman.20 By a forty-

seven to forty-four vote, however, the

open ballot prevailed. The nomination fol-

lowed, and Sherman became the party's

choice, obtaining fifty-three votes, includ-

ing Daugherty's, to Foraker's

thirty-eight. This vote insured Sherman's election

since the Republicans dominated the General

Assembly.

In several editorials following the

caucus, the Democratic Columbus Post ac-

cused Daugherty and fourteen other

legislators of changing their pledges from

Foraker to Sherman because of

"intimidation, threats, promises and actual pur-

16. Foraker to Kurtz, December 4, 1891,

uncatalogued Kurtz Papers.

17. William Hahn to Sherman, December

11, 1891, Vol. 560; December 15, 1891, Vol. 561, Sher-

man Papers.

18. Daugherty showed Foraker the pledge

statement on December 29. Although he did not indicate

when he had signed it, his mid-December meetings with

Hahn and Sherman seemed the only logical

time. Foraker to Daugherty, January 18,

1892, Box 27, Foraker Papers.

19. Ibid.

20. Cyclone and Fayette Republican, January

7, 1892.

158

OHIO HISTORY

chase" and claimed explicitly that

Hahn had paid Daugherty for his vote.21 A grand

jury investigation of the charges ended

without returning any indictments. Foraker,

who would have made an interesting

witness, refused to cooperate with the inquiry.

"As to the grand jury

business," he wrote Kurtz, "I sincerely hope that no friend

of mine will have anything whatever to

do with it." He made it clear that he would

not accept responsibility for the

disclosure of any charges. The contest, according

to Foraker, had ended with the caucus.22

Intraparty unity prevailed to oppose any

threat of exposure by an outside force.

The grand jury's failure to return any

indictment against him enabled Daugherty

to act. In a speech in the house on

January 26, he asked for a bi-partisan commit-

tee to investigate the Post charges.23

Daugherty expected full vindication of the

accusations. He went into the inquiry

with letters from both Sherman and Foraker

attesting that he had acted honorably in

the senatorial contest.24 The select house

committee of two Republicans and two

Democrats conducted an investigation

which extended into April. The Columbus Post

manager, Charles Q. Davis, failed

to substantiate his charge that

Daugherty had accepted a bribe. Davis' accusation

was, in part, based upon an alleged

conversation he had overheard between

Daugherty and an unidentified person

near a cigar stand in the Neil House some-

time before the caucus. Daugherty,

according to Davis, had commented that Sher-

man would not receive his vote unless he

"put up for it." Davis had no witness

to confirm Daugherty's supposed

statement. The Post's charge that Hahn had

withdrawn seven $500 bills from the

Deshler National Bank of Columbus on the

day of the caucus and had used the money

to bribe Daugherty met the same fate,

for again proof was not forthcoming.25

Neither Daugherty nor Sherman, however,

was completely honest in his testi-

mony at the committee's hearings.

Daugherty amazingly testified that he had con-

sistently supported Sherman's candidacy

since the August resolutions of the

Fayette County convention. Sherman's

testimony was also misleading. Choosing

to ignore Daugherty's trip to Washington

in mid-December, he said that he did

not know anything about Daugherty's

position on the senatorial contest aside from

what he had heard from Fayette

Republicans. Indeed, Sherman claimed that he

had never seen Daugherty during the

entire preliminary canvass. It was not, ac-

cording to Sherman, until two or three

days before the speakership contest that he

had first talked to him about the

campaign.26

Daugherty was unanimously exonerated by

the house committee in April. To

Daugherty the matter "was so well

settled that there is no one believing any of

the charges against me or any of the

gentlemen mentioned by the paper."27 He

was right in one respect. The Post's inability

to substantiate its charges damaged

21. Ohio General Assembly, House

Journal, 1892, Appendix, "In the Matter of the Investigation

of the Charges Published in the Columbus

Post, vs. Hon. H. M. Daugherty, in the Recent Senatorial

Contest," 30, 39. Cited hereinafter

as "Senatorial Investigation."

22. Foraker to Kurtz, January 14, 1892,

uncatalogued Kurtz Papers.

23. Cincinnati Enquirer, January

27, 1892.

24. Daugherty wrote freely and

extensively to Sherman in this period. His response to Sherman's

letter exonerating him especially

revealed his gratitude. He said: "I will long preserve the letter and

hand it down to those I love. I would

rather have that letter Senator than the $3,500 I have been

charged as having received for voting

for you." Daugherty to Sherman, January 19, 1892, Vol. 573,

Sherman Papers.

25. "Senatorial

Investigation," 47, 63.

26. Ibid., 64, 68.

27. Daugherty to Sherman, May 6, 1892,

Vol. 579, Sherman Papers.

Harry M. Daugherty 159

the paper's reputation, and it shortly

suspended publication without any compen-

sation to its staff for salary due them.

Daugherty distributed $1800 among the

hard-pressed staff with the wry remark

that thete were no "crisp $500 bills" in

the disbursement. He then filed suit

against the Post, recovered staff salaries, and

made no charge for legal services.28

The senatorial contest altered

Daugherty's political career. He became a mem-

ber of the Sherman-Hanna-McKinley wing

of the party after previously associa-

ting with the Foraker element. Upon the

convening of the General Assembly in

January 1892, House Speaker Lewis C.

Laylin appointed Daugherty chairman of

the important corporations committee and

placed him on the judiciary committee.

Meanwhile, Foraker representatives were

excluded from all chairmanships.29 The

Sherman faction also selected Daugherty

chairman of the house caucus, entrusting

him with the responsibility of

organizing party legislative support for Governor

McKinley's programs. Daugherty, in later

years, claimed that all McKinley had

to do was talk to him about what he

wanted done, and, as leader of the house,

he would put it into effect.30

Despite the immediate favors the Sherman

wing provided Daugherty, his in-

volvement in the senatorial contest had

an adverse result. It cost him the support

of Foraker and his many followers. Kurtz

later remarked sarcastically that he saw

little of Daugherty after their last

meeting in 1891 when promised support for

Foraker failed to materialize. After

this, Daugherty's actions continued to cast a

shadow over his later career as critics

often alluded to his alleged duplicity. Even

as late as 1920 the New York World opposed

Daugherty's appointment as attorney

general in part because it questioned

his conduct in 1892.31

Nevertheless, as his second term in the

house drew to a close, Daugherty itched

for higher public office. This was

certainly an auspicious time, for McKinley was

serving his final term as governor. The

task of choosing a successor fell upon the

1895 Republican state convention.

Daugherty thought himself its worthy prospect.

Indeed, he had rendered McKinley no

little support while he had been Republi-

can floor leader in the house. In 1893,

as chairman of the state convention, he had

backed McKinley's gubernatorial

renomination and had introduced a resolution

endorsing his administration at the

Fayette County convention the following spring.32

Even so, Hanna made it known that he

would favor Judge George K. Nash of Co-

lumbus. Daugherty, however, secured the

allegiance of the Hanna organization for

the attorney general nomination upon realizing

that he had little support from them

for governor. Despite opposition from

some Fayette Republicans, he also received

the county organization's endorsement

and obtained its authorization to select

Fayette's delegation to the May 28-29

state convention at Zanesville.33 His friends

chartered a special Pullman sleeper for

the entourage. On the side of the car as it

28. Samuel Hopkins Adams, Incredible

Era: The Life and Times of Warren G. Harding (Boston,

1939), 40-41.

29. Cincinnati Enquirer, January

13, 1892.

30. Daugherty to Ray Baker Harris, June

7, 1938, Box 9, Ray Baker Harris Collection, Ohio His-

torical Society.

31. Cox, Journey, 304; New York World,

February 17, 1921.

32. Ohio State Journal (Columbus),

June 9, 1893; Cyclone and Fayette Republican, June 7, 1894.

33. Cincinnati Enquirer, May 19,

1895. The opposition came from a Fayette Republican faction that

condemned Daugherty's conduct in the

1891 senatorial contest and resented his efforts to dominate the

county Republican organization. In 1892

this faction had prevented Daugherty from obtaining the

county Republican convention's

endorsement for United States Congress. See also Cyclone and Fayette

Republican, June 23, 30, 1892.

160 OHIO

HISTORY

left Washington Court House on the

evening of May 27 was a large streamer, "For

Attorney General, Harry M. Daugherty of

Fayette." The train first stopped at

Bloomington in Paint Township. The

Bloomington Republican women presented

Daugherty with a huge floral bouquet

with an attached "Paint Township for

Daugherty" card. He was the

recipient of additional boosting before the train pulled

into the Zanesville station.34

Zanesville was a compromise site between

the Foraker faction who had wanted

Cincinnati and the Hanna-Sherman forces

who had favored Columbus. As it turned

out, this was one of the few convention

compromises Foraker made. His tactics

surprised the opposition so completely

that he was able to dominate the convention.

He received the endorsement of the

delegates for Senator in 1896, wrote the party

platform, and chose almost the entire

state ticket, including the gubernatorial

nominee, Asa S. Bushnell. Since Foraker

controlled the key committees and many

of the large delegations, Hanna and

Sherman were both rendered powerless. Their

only consolation was that McKinley was

endorsed for the Presidency in 1896.35

Foraker's convention strength weakened

Daugherty's nomination chances. He

was hardly Foraker's personal choice for

attorney general; indeed, Foraker wanted

William L. Parmenter of Lima. On the

first two ballots, however, Daugherty and

Frank S. Monnett of Bucyrus were the leaders

with Parmenter a poor third. On

the following ballot, Hamilton County

Boss George B. Cox gave his delegation's

eight votes to Foraker's alternate

choice, Monnett. The result was inevitable; Mon-

nett defeated Daugherty 486 to 236.36

The newspapers blamed Daugherty's defeat

on geographical considerations.

Bushnell came from southern Clark

County, and many of the other nominees who

preceded Monnett's selection were from

southern Ohio. Logic dictated that the

ticket be balanced geographically by

nominating a northern Ohioan for attorney

general. Thus, Monnett and Parmenter

were more suitable choices.37 Actually it

probably mattered little to Foraker and

Kurtz whether Daugherty was from north-

ern or southern Ohio. Daugherty, more

significantly, had offended Foraker in

1891; he was now considered a strong

Hanna-Sherman man. It was ironic that

Foraker's political comeback paralleled

Daugherty's rising political ambitions.

Although he lost a tough fight at

Zanesville, Daugherty won at least a moral

victory. He not only brought with him a

united delegation of "stalwarts" but was

able to make a good impression among

delegates from other counties. Many were

or would become loyal friends. No

headquarters was as crowded as Daugherty's

with well-wishers and allies.38

By mid-February 1896 Daugherty again

aspired for public office. He announced

in an interview with the Cyclone and

Fayette Republican that he was a candidate

for the United States Congress provided

Fayette held a Republican primary pre-

ceding the congressional convention and

that a majority of the county Republi-

cans voted for him.39 Daugherty

stated later that the 1896 primary was his most

bitter fight in politics. Blaming his

participation in a recent controversial trial as

the cause, he claimed that feeling

against him was so great in the county that the

34. Ibid., May 30, 1895; Ohio

State Journal, May 28, 1895.

35. Walters, Foraker, 108-109.

36. Cincinnati Enquirer, May 30,

1895.

37. Ibid.; Ohio State Journal, May

30, 1895; Cyclone and Fayette Republican, May 30, 1895.

38. Ibid.

39. Ibid., February 20, 1896.

Harry M. Daugherty 161

harness was removed from his horse while

he was addressing a rally.40 Neverthe-

less, on March 14 Daugherty defeated A.

R. Creamer by 109 votes in the Repub-

lican primary county election.

Editorials of the Cyclone and Fayette Republican

helped Daugherty since they associated

Creamer with the "mugwumpery" which

had attempted to weaken the Republican

county organization in 1892. His loyalty

was in doubt as he did not declare his

support for the Republican candidate "who-

ever it might be" and had been

nominated by a Democrat for mayor of Washing-

ton Court House at the same time he was

running for congress on the Republican

ticket.41

To win the congressional nomination from

his district, Daugherty had to re-

ceive party endorsement at the seventh

United States congressional district con-

vention at Springfield. Just prior to

the convention, Mark Hanna asked Daugherty,

the chairman, to insure that it select

pro-McKinley delegates to support the gov-

ernor's presidential ambitions at the

Republican national convention in St. Louis

that summer.42 This was

incompatible with Daugherty's nomination strategy for

the congress.

Daugherty's plan centered upon Madison

County, one of five counties which

comprised the seventh congressional

district. Pickaway and Miami sent anti-

McKinley delegations to the Springfield

convention while Fayette and Clark were

both for McKinley. The balance rested

with Madison which dispatched two dele-

gations, each contesting for the right

to be seated. George F. Wilson, the incum-

bent McKinley-Hanna congressional

candidate, headed one, and John Locke led

the anti-McKinley group. Locke had

promised Daugherty that he would commit

his county's twenty votes to him,

provided that Fayette voted to recognize his rump

delegation. This would have given

Daugherty fifty-nine votes, more than enough

for the nomination.43

Daugherty elected to change his plans

upon hearing from Hanna. He had no

choice but to drop his original scheme

unless he wished to alienate the party boss.

He wired Hanna that he would "seat

the Wilson delegation from Madison [even]

if they cut my throat a moment

later." After the pro-McKinley delegation had

been selected and Daugherty had lost the

congressional nomination to Walter L.

Weaver of Clark County, he again

telegrammed Hanna that he had "seated the

Wilson delegation, and they have cut my

throat."44 Daugherty's only consolation

was that he had been selected to be a

delegate to the Republican national conven-

tion in June.

That fall Daugherty worked hard in

behalf of the national ticket. The McKinley-

Bryan presidential campaign developed

into an extremely crucial contest. The

Democrats' acceptance of free silver

threatened to crystalize over twenty years of

dissatisfaction with Republicanism among

the farming and laboring elements.

Daugherty traveled over nine thousand

miles in the campaign. At the request of

the Republican national committee, he

spoke in Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin,

Minnesota, Nebraska, Kansas, and South

Dakota. Generally, his attack was focused

on the unfairness of free silver. He

spoke at Howard, South Dakota, a few hours

40. Daugherty to Harris, June 7, 1938,

Box 9, Harris Collection. Daugherty defended Colonel Alonzo

Coit who had ordered his National Guard

troops to fire into an angry Washington Court House crowd

that was attempting to lynch a Negro

rapist who was under Coit's custody.

41. Cyclone and Fayette Republican, March

5, 12, 19, 1896.

42. Cincinnati Enquirer, May 21,

1899.

43. Ibid.

44. Ibid.

162 OHIO

HISTORY

after Populist Mary Lease, to contest

her denunciations of McKinleyism and the

gold standard. The Cyclone and

Fayette Republican claimed that at the conclusion

of his speech Daugherty received

"three rousing cheers."45

In 1897 Daugherty gained some

recognition for his work for McKinley in the

previous years. At the June Republican

state convention in Toledo, he was selected

chairman of the Republican state central

committee, the most important party office

in Ohio.46 The Hanna forces

dominated the convention itself as the Foraker faction

had done in 1895. Although Foraker was

fortunate in securing the gubernatorial

nomination for Bushnell, it was all that

he and his lieutenants were able to obtain.

George K. Nash replaced Charles Kurtz as

chairman of the state executive com-

mittee, putting the pro-Hanna Nash in

charge of the campaign.

The fall contest of 1897 indirectly led

to Daugherty's first altercation with Hanna.

Having been appointed to the Senate in

February after Sherman became McKinley's

Secretary of State, Hanna was now

anxious to be elected in his own right. For the

first time in his career, he went on the

stump in an effort to insure the selection of

pro-Hanna legislators at the November

polls. Despite the opposition of the Foraker

faction and Democrats, Hanna appeared to

have secured enough pledges as the

result of the election.47 Nevertheless,

Foraker's lieutenants collaborated with Dem-

ocrats in the post-election period in an

effort to win over some of the Hanna pledges.

Led by such pro-Foraker leaders as Kurtz

and Republican Mayor Robert E. Mc-

Kisson of Cleveland, they seemed to have

enough support to defeat Hanna by the

time the General Assembly convened in

early January. However, Hanna won by

the narrowest of margins. An anti-Hanna

Republican, James Otis, thought Hanna

bought votes to win and accused a Hanna

agent of bribery even before the final

vote in the legislature. On the morning

of the Assembly contest, state senator

Vernon Burke introduced a resolution

calling for the investigation of the bribery

charges. Quickly, the United States

Senate appointed a committee of investiga-

tion which was to submit a report to the

Senate committee on privileges and elec-

tions as to whether Hanna should be

re-seated or expelled.48

Hanna's friends thought it imperative

that he be represented with counsel to

keep him informed as to the progress of

the committee as well as to safeguard his

own interests. Charles Dick, secretary

of the Republican national committee, em-

ployed Daugherty and Cyrus H. Huling, a

Columbus attorney-politician, to rep-

resent Hanna.49 This

seemingly routine matter contributed to a rift between

Daugherty and Hanna which began in 1898.

Though it was closed temporarily,

it still remained unresolved at Hanna's

death in 1904.

Disagreement first occurred in May 1898

after the state senate committee and

the committee on privileges and

elections failed to find enough evidence to impli-

cate Hanna or his friends. On May 16

Daugherty wrote Hanna enclosing bills to

the Republican national committee

totaling $7500. The payment was to be divided

among Daugherty, Huling, and a G. L.

Marble, an attorney from Paulding County,

for legal services in Hanna's behalf.

Daugherty justified these charges in alluding

to the "constant and careful

work" that he and his associates had performed

45. Cyclone and Fayette Republican, September 17, October 8, 1896.

46. Ohio State Journal, June 24, 1897.

47. Croly, Hana, 250-251.

48. Ibid., 251-259, 259-260.

49. According to Huling, Judge George K.

Nash advised Dick to employ counsel. Nash most likely

suggested both Daugherty and Huling.

Cincinnati Enquirer, May 12, 1899.

|

throughout the investigation, claiming that he had practically set aside his other legal work from January to May because of his extensive surveillance of the state committee. He believed the Republican national committee should pay the expense since Hanna was its chairman and the attack was indirectly centered upon the Republican party.50 Secretary Dick, who first read the letter, quickly replied that Daugherty's services were not a national committee matter and even if they were the committee did not have sufficient funds. He concluded his letter to Daugherty by questioning various aspects of the bills: It appears to me the bills are exorbitant and entirely out of proportion and I am sure they will so impress the Senator. I know nothing of the employmeny [sic] of Mr. Marble; by whose authority or for what purpose he was retained in the matter. I don't think the matter ought to be presented to the Senator in this shape and I believe after you have had an opportunity to consider it you will thank me for speaking frankly.51 Daugherty refused to make revisions in the fee. He replied that Dick's "conduct in regard to our communications to Senator Hanna is a great surprise and an insult to us," so he informed the secretary the trio was coming to Washington to speak to Hanna personally. Daugherty ended the letter forcefully saying, "We are as unwill- 50. Daugherty to Mark Hanna, May 16, 1898, Box 1, Charles Dick Papers, Ohio Historical Society. See also George A. Myers to James Ford Rhodes, April 30, 1920, cited in John Garraty, ed., The Barber and the Historian: The Correspondence of George A. Myers and James Ford Rhodes, 1910-1923 (Colum- bus, 1956), 106-107. 51. Charles Dick to Daugherty, May 19, 1898, Box 1, Dick Papers. |

164 OHIO

HISTORY

ing to impose on Senator Hanna as you

are, and we are also equally unwilling to

be imposed upon."52

There are two accounts of Hanna's

reaction to Daugherty's insistence that he or

the Republican national committee pay

the $7500. Dick stated the following year

that when he had asked Hanna what he

should do, Hanna had replied: "Do? Do

nothing, that's what the fellows have

done--nothing. Put it all in the hands of Andy

Squire and let him settle."53 George

A. Myers of Cleveland, a barber and local

Hanna politician, in his correspondence

with historian James Ford Rhodes over

twenty years later, elaborated upon the

Senator's recoil. Myers claimed that Hanna

had said: "pay the ---- --- ----

and let him go."54 Whatever his specific

response, Hanna was annoyed, even though

he eventually paid Daugherty.

The differences between Daugherty and

Hanna subsided within a month. In

fact, it appeared that no disagreement

had occurred. At the June 21-22 Republican

state convention at Columbus, Daugherty

became chairman of the state executive

committee and his friend Huling replaced

him as state central committee chairman.

Hanna men were instrumental in these

selections. Busily occupied in Washington,

Hanna did not attend and, therefore,

played no part in the convention proceedings.

It is doubtful, however, that Daugherty

was Hanna's choice, although he did not

feel strongly enough about the outcome

to prevent it. As chairman, Daugherty

engineered the successful Republican

campaign that fall. Secretary of state Charles

Kinney, the head of the ticket, easily

won reelection.55

Daugherty broke with Hanna the following

year. The break came over Daugher-

ty's desire to seek the Republican

gubernatorial nomination. Deterred in 1895,

Daugherty had decided in the summer of

1898 that he must make the race in 1899.56

Bushnell was approaching his last year

of two terms. There might not be another

opportunity until 1903 if Bushnell's

successor were a Republican. Besides, Daugherty

felt that the administration owed him an

open field for he had worked extensively

for the McKinley organization since

1892.

Both Ohio Senators rejected Daugherty's

candidacy. On January 5, 1899, Senator

Foraker sarcastically said in an

interview that it was "natural" for him to be for

Daugherty since Daugherty had provided

such loyal support in the 1892 senatorial

contest. A day later the Cincinnati Enquirer

predicted that George K. Nash was

Hanna's choice for the nomination,

although Hanna had not as yet openly sup-

ported any candidate.57 Daugherty

visited Hanna in Washington later that month

to tell him "that a free field and

no favor would be a desirable thing in Ohio . . ."58

In early March, however, Hanna told him

that it was not his year to make the race.

Nevertheless, Daugherty announced that

Hanna favored his nomination.59

Daugherty and his followers attempted to

create the impression that the Hanna

organization regarded him as favorably

as Nash. On May 10 this strategy came

into question when either Charles Dick

or one of his lieutenants released a state-

ment to the Enquirer, elaborating

upon how Daugherty "held up" Hanna in the

bribery investigation the previous year. In a rebuttal the following day,

Cyrus Huling

52. Daugherty, Huling, and Marble to

Dick, May 27, 1898, ibid.

53. Cincinnati Enquirer, May 10,

1899. Andrew Squire was Hanna's personal attorney.

54. Myers to Rhodes, May 22, 1922,

Garraty, Barber and the Historian, 145.

55. Ohio State Journal, June 23,

November 10, 1898.

56. Kurtz to Foraker, June 3, 1898, Box

36, Foraker Papers. Kurtz wrote Foraker that "stranger

things than this have come to

pass."

57. Cincinnati Enquirer, January

6, 1899.

58. Ohio State Journal, January

23, 1899.

59. Cincinnati Enquirer, May 15,

1899.

Harry M. Daugherty

165

claimed that the fee was reasonable and

justified because of the extent of the work.

Daugherty and Huling then proceeded to

attack Dick in the various newspapers

exchanges that week. They portrayed Dick

as a jealous man who resented Daugh-

erty's elevation to chairman of the

state Republican executive committee. The

"selfish" Dick, they wrote,

was deliberately using his position with Hanna to curb

Daugherty's influence in the party.60

Because of the publicized fight with

Dick, Daugherty was no longer able to

assert that Hanna approved of his

candidacy. It was evident that the "puppet"

Dick and other Hanna men would not have

generated the anti-Daugherty publicity

without Hanna's approval. All had not

ended for Daugherty, however; his control

of the Republican state executive and

the state central committees enabled him to

dominate the nominating convention

organization. The Republican convention tem-

porary and permanent chairmen both would

be Daugherty men. He also had the

support of dissident forces who resented

Hanna's domination of the Ohio party.

James W. Holcomb, who had fought the

pro-Foraker McKisson and the Hanna

forces in Cleveland to a standstill, was

in constant communication with Daugherty

before the Republican convention. In

addition, Daugherty had his own organization

of loyal followers which included

Huling, Charles Kinney, Ohio secretary of state,

and Howard Mannington, former Ohio assistant

secretary of state and now Daugh-

erty's campaign manager. Daugherty's

strategy precluded any attempt to align with

the anti-Hanna Foraker crowd. He planned

to present his case before the delegates

as a deserving McKinley-Hanna man who

sought an open convention in which

Hanna would not dictate. His fight,

however, was not so much one of principle as

he himself claimed. He believed in the

same boss-oriented party system as Hanna.61

In the week before June 1, the convening

date of the state convention in Colum-

bus, Daugherty appeared to have the

backing of most of the delegates selected at

the various Republican county

conventions. Judge Nash, Hanna's choice, closely

followed, with Lieutenant Governor Asa

Jones, Foraker's candidate, a poor third.

On May 27 Daugherty announced at his

Neil House headquarters that at least

350 delegates were pledged to him, while

Nash's managers stated that their candi-

date had about 275 votes.62 On

the following day McKinley declared in a Washing-

ton interview that "Daugherty is a

good fellow and would make a good governor."

Concerned about the growing party rift

in Ohio, the President, however, refrained

from endorsing any particular candidate.63

Early in the preparations for the

convention battle, some of Daugherty's managers

had journeyed to Cincinnati for a

meeting with Boss George B. Cox. It was claimed

after the Nash victory that an agreement

had been made pertaining to the committee

of credentials. Not only had this

assured the seating of the contested Holcomb and

Cox delegations, but also the agreement

created the possibility of Cox eventually

swinging his delegation to the support

of Daugherty--which he did not do. David

Walker, Daugherty's brother-in-law,

later asserted that Cox in the Cincinnati meet-

ing had promised at least not to use his

votes in Nash's behalf.64 As a result of this

understanding Daugherty's men had

returned to Columbus with the firm belief that

they need have no fear that Nash would get any votes in

Hamilton County, and the

60. Ibid., May 10, 11, 12, 1899.

61. Ibid., May 10, 12, 17, June

3, 1899. On May 14, 1899, Hanna was reported to have favored a

mass convention for the selection of

delegates from Cuyahoga County to the state convention.

62. Ohio State Journal, May 28,

1899.

63. Cincinnati Enquirer, May 29,

1899.

64. Ibid., June 4, 1899.

166 OHIO

HISTORY

plans for Daugherty's candidacy were

made accordingly.

On the day before the opening of the

convention Daugherty left his headquarters

and walked down the Neil House corridor

to Hanna's rooms, even though Hanna

had earlier failed to award recognition

to the Daugherty group as he passed by the

aspiring governor's headquarters. The

men shook hands, whereupon Hanna said,

"Well, Harry, this is a great fight

that you have been putting up." Daugherty re-

torted that it was not a fight but a

contest. He went on to say that he did not relish

being denounced as an

anti-administration man. Hanna replied, "That is wrong,

Harry, I consider . . . you . . . as

good an Administration man as I am."65 This was

Daugherty's last conversation with Hanna

until after the "contest."

Daugherty's chances for success faltered

in the early hours of convention morn-

ing because of the decisions made in a

number of conferences held from the previ-

ous evening until the convention opened

the next day. The most important was

made in a Cox-Hanna meeting just after

midnight. Cox, who had preferred a com-

promise candidate from Hamilton County,

agreed to favor Nash until the third

ballot in exchange for Hanna's promise

to nominate Cincinnati ex-mayor John A.

Caldwell for lieutenant governor.66

Cox's eighty-six votes from Hamilton gave Nash

a tremendous advantage.

James Holcomb nominated Harry Daugherty

on the second day of the conven-

tion. According to the Cleveland Plain

Dealer, the cheering which followed Hol-

comb's speech meant very little as the

men who cheered were soon ready for the

slaughter.67 Nash led

Daugherty at the end of the first ballot, 289 to 211. On the

second vote, Nash was nominated as Cox

swung his eighty-six delegates over to

the Hanna side, encouraging other

delegations to follow. Nash received 461 to

Daugherty's 205 votes on the final

ballot. Amid the demonstration, Daugherty

walked to the platform where he spoke

briefly:

This is a good deal like a man dancing a

jig at his own funeral, nevertheless there is a

great deal of pleasure in doing it. I

thought it might be becoming in me ... to come before

the convention and say to you . . . that

I cheerfully ratify the choice of this convention. To

my friends . . . I have nothing to offer

but sincere thanks. To those who have supported

the victor in this contest, I bear no

malice.

I will remain a private citizen-not,

perhaps, because of my own choice, because that is

a privilege that no man dare deny me. I

am determined to have my own way about some-

thing.68

Daugherty waged a good fight in spite of

being opposed by the Hanna and the

Foraker factions-the two major wings of

the Ohio party. His smooth organization

surprised both Hanna and Nash. He failed

to win not only because of the duplicity

of Cox but also because Hanna was

adamant in his refusal to allow an open con-

vention. Although many pro-Hanna

delegates had favored Daugherty, they were

reluctant to vote for him when it became

clear that Nash was Hanna's choice.69

They had their state jobs, patronage, or

political influence to weigh against a candi-

date who was unable to assure them of

certain success.70

65. Ibid., June 1, 1899.

66. Ibid., June 3, 1899.

67. Cleveland Plain Dealer, June

3, 1899.

68. Ohio State Journal, June 3,

1899.

69. Cincinnati Enquirer, June 2,

3, 1899.

70. See, for example, William H.

Phipps to Daugherty, May 22, 1899, Box 1, William H. Phipps

Papers, Ohio Historical Society.

|

|

|

Harry Daugherty's political career was temporarily frustrated as the result of his defeat. He was never included in the party councils as long as Hanna lived or Hanna's senatorial successor Charles Dick remained powerful. His punishment began immediately after the 1899 Republican state convention. Dick replaced Daugherty as chairman of the state executive committee and pro-Hanna Myron Norris of Youngstown became Cyrus Huling's successor as state committee chairman. By 1901 the Hanna men even contested Daugherty's control of the party organization in Fayette County.71 For the first time since 1888 he was not a delegate to a state Republican convention. His political sway had reached its. lowest ebb. It was 1906 before Daugherty effectively challenged the party organizations that Dick and Foraker dominated. Allied with him were Theodore Burton, the scholarly congressman from Cleveland, and the opportunistic Myron T. Herrick, the recently defeated Ohio governor. The insurgent movement which these three led ascribed to the same progressive principles that were currently toppling political machines 71. The Enquirer published several articles on Daugherty's proposed punishment in the week fol- lowing the election. See, June 3, 6, 1899; June 20, 1901. Although Daugherty had moved to Columbus in 1894, he continued to control politics in Fayette. |

168

OHIO HISTORY

and boss-rule in various states

throughout the country. In the same fashion, this

group sought the removal of Dick and

Foraker from the control of the state party

organizations.72 "The

Republican party," according to Daugherty, "needs no bosses,

and all the semblance of bossism should

be avoided by its representatives."73 It

was only natural that Daugherty should

attempt to play a leading role in this move-

ment. The Dick and Foraker combination

had relegated him to political obscurity.

Only after curbing their influence could

he hope to secure the gubernatorial nomi-

nation and play a stronger part in the

party.74

The main Daugherty-Burton-Herrick

challenge came at the September Republi-

can state convention at Dayton. In

various caucuses, they attempted to remove

Dick as chairman of the state Republican

executive committee and prevent the

pro-Dick Walter F. brown, the political

boss of Toledo, from becoming the new

chairman of the party's central

committee. In each instance the insurgents lacked

the necessary strength.75 Nevertheless,

Daugherty and Burton carried the fight to

the convention floor. They ascended the

rostrum to argue against Dick's continu-

ance as chairman. They opposed the

unqualified endorsement of Dick and Foraker

as United States senators. Burton also

introduced resolutions for tariff revision and

for the nomination of United States

senators by primary vote. In every case the

insurgents suffered a reversal as their

opponents proved too formidable.76 Warren

G. Harding, the former lieutenant

governor from Marion, strongly opposed Daugh-

erty and other insurgents throughout

this fight.77

Never one to crumble under adversity,

Daugherty recovered quickly from his

1906 setback. Because of his

anti-Foraker-Dick stance, he moved naturally--and

opportunistically--into the rising

William Howard Taft camp in Ohio. By 1908

Daugherty played an active part in

Taft's presidential nomination and viewed with

satisfaction the collapse of the

anti-Taft Foraker-Dick organizations.78 Still, his ambi-

tions for high public office failed to

materialize. Because of Burton's candidacy in

1908, Daugherty withdrew his efforts to

win the United States senatorial nomina-

tion, by now his most important

political goal. He again foundered in 1910 when

the Democrats gained control of both

houses of the state legislature.79

By 1912 the Taft-Theodore Roosevelt feud

elevated the increasingly thickset and

middle-aged Daugherty into the political

limelight of Ohio politics. In this intra-

party battle between conservatives and

progressives, he strongly supported the

former, reversing the stand he had taken

in 1906 when Ohio Republican insurgents

first challenged the existing order.

Daugherty was not inconsistent in aligning him-

self with Taft. In fact he had helped

considerably in the 1908 campaign and had

later favored his administration.

Daugherty considered Taft an honest, capable

72. Walters, Foraker, 256. See

also Arthur Garford to Daugherty, August 17, 1906, Box 18, Arthur

Garford Papers, Ohio Historical Society.

73. Cleveland Plain Dealer, August

26, 1906.

74. "I note that the papers quote

you as saying that you will be a candidate for governor to suc-

ceed Pattison," Phipps to Daugherty, December 11,

1905, Box 7, Phipps Papers. In answer to Phipps,

Daugherty replied, "I note what you

say in regard to the governorship, I have not said I would be a

candidate . . . I did say that on the

first of January, 1906, I will announce whether I will be a candidate

or not." Daugherty to Phipps,

December 12, 1905, ibid.

75. Ohio State Journal, September 12, 1906.

76. Ibid., September 13, 1906.

77. Cleveland Plain Dealer, August

26, 1906.

78. Philadelphia Record, December

17, 1908. Clipping in Theodore Burton Papers, Box 67, Western

Reserve Historical Society.

79. Forrest Crissey, Theodore Burton:

American Statesman (Cleveland, 1956), 75. See also Ohio

State Journal, January 11, 1911.

Harry M. Daugherty 169

president who was entitled to the

party's nomination, and as a candidate more in

tune with his own brand of conservative

Republicanism, which remained consistent

throughout his life aside from that one

detour in 1906.80 Taft was also an Ohioan--

one who was not ambivalent toward

Daugherty's political ambitions. In any case,

he expected Taft's organization to

support him in any future senatorial campaign.81

For whatever specific reason, Daugherty

was one of the most active Taft men

in Ohio in the early months of that

hectic year of 1912. He and Ohio national

committeeman Arthur Vorys devoted much

time to planning Taft's Ohio primary

campaign. So appreciative was the President

that he wrote Daugherty a personal

note in March thanking him for his

efforts.82 Probably no amount of work, however,

could have prevented the humiliation

Taft suffered in the Ohio May primary.

Thirty-four Roosevelt delegates were

elected to eight for Taft, with only six delegates-

at-large to be chosen at the June state

Republican convention. These Taft managed

to secure during a bitterly contested

meeting in which hisses and catcalls interrupted

speeches from both factions.83 Largely

because he also controlled the national party

machinery, Taft succeeded in winning

renomination at the Republican national con-

vention in Chicago the same month.

Taft's steamroller victory caused

Roosevelt to create the Progressive party in

August. In Ohio a number of progressive

Republican leaders joined the Bull Moose

movement upon Taft's refusal to

compromise on the issue of his presidential en-

dorsement. With the Ohio Republican

party now badly weakened, Harry Daugherty

agreed to serve as chairman of the

Republican state executive committee. His task

was to lead the sagging state party to

victory against the Democrats and Progres-

sives in November. He believed that his

only hope for success was to conduct a

disciplined campaign in which all disloyal

Republicans would be purged from the

party. In a series of directives, he

proceeded to eliminate all anti-Taft and pro-

Progressive members from the county

committees and advised all committees not

to aid financially any disloyal

Republican candidate. He also worked with Ohio

secretary of state, Charles H. Graves (a

Democrat), to enforce the controversial

Dana Law, which permitted a candidate to

represent only one party on the ballot.84

No longer could Republican candidates

running on the congressional and county

levels carry "water on both

shoulders" in order to win the Progressive party en-

dorsement. Consequently, the Progressive

party was eliminated as a factor on the

local plateau.

In pursuing such policies, Daugherty had

encouragement from almost all

pro-Taft Republicans. In fact, it was in

this period that a Daugherty-Harding part-

80. Harry M. Daugherty and Thomas Dixon,

The Inside Story of the Harding Tragedy (New York,

1932), 80. See also Daugherty to

Harris, May 4, June 7, 1938, Box 9, Harris Collection.

81. Cleveland Leader, June 17,

1912; Ohio State Journal, August 7, 1912. Taft had already sup-

ported him in other ways. In January

1912 he commuted the sentence of a Federal prisoner, Charles

W. Morse, in part because of Daugherty's

lobbying activities in Morse's behalf. On innumerable occa-

sions the lobbyist Daugherty attempted

to use his political associations to benefit his legal work. For

the sordid Morse case see Henry

F. Pringle, The Life and Times of William Howard Taft (New York,

1939), II, 627-637.

82. William Howard Taft to Daugherty,

March 12, 1912, William Howard Taft Papers, Folder 335,

Presidential Series II, Library of

Congress.

83. Daugherty and Harding were included

among the "big six."

84. Daugherty to Edward H. Cooper,

October 21, 1912, Box 21, Phipps Papers; Daugherty to County

Chairmen, November 7, 1912, ibid.; Newton

Fairbanks to Myron T. Herrick, February 8, 1916, Box 1,

Newton Fairbanks Papers, Ohio Historical

Society; and Ohio State Journal, September 1, 25, October

1, 1912.

170

OHIO HISTORY

nership evolved.85 Harding,

who had placed Taft's name in nomination at the

Republican national convention, had

attempted to harmonize party differences.

Failing in this, he became a strong

defender of Daugherty's uncompromising ac-

tions. The Harding Marion Star gave

Daugherty its complete backing. Daugherty

cordially thanked Harding for his

"constant comfort and support during the

campaign . . . It was only on account of

such support," reported Daugherty, that

he was able "to go through this

terrific fight." In another letter, he claimed that

"we are better friends than ever

and understand each other thoroughly and will

hang together through thick and thin."86

The election results, however, proved a

disappointment to Daugherty. Obviously

the Republican party split was the

opposition's gain. Yet his disciplined campaign

kept the party organizations intact in

the face of the Progressive assault. The fact

that he prevented Republican candidates

from receiving Progressive endorsements

did much to retain the integrity of the

Ohio party. Confident of his course and

anxious to maintain control, he

continued his strong anti-Progressive measures into

the post-election period.87

This approach satisfied such Old Guard

faithfuls as Taft and Foraker but caused

ill-feeling among many Republicans who

now felt that the main task should be a

reunion of Progressives and Republicans.88

Some, in fact, believed that Daugherty's

resignation as party chairman was a

needed prerequisite for a reunited party.89 In

the months after 1912, however, chairman

Daugherty continually hindered the

possibility of any meaningful

Republican-Progressive amalgamation. Not only refus-

ing to relinquish the party executive

chairmanship to a more harmonious leader, he

also opposed any compromises that

questioned the principles he had defended in

1912. Nor did he favor the return of

Progressive leaders to positions within the

Republican party."90

Although sometimes as uncompromising as

Daugherty in 1912, Warren G.

Harding by early 1914 had the reputation

of being a harmonizer and he wisely

focused on the need for an inclusive and

reunited party.91 He was at that time a

prime senatorial contender to replace

the retiring Theodore Burton, particularly

since his main primary opponent was the

reactionary Joseph Foraker. Harding

developed a strong appreciation for

Daugherty's support which led to the 1914

senatorial victory. He also believed

that Daugherty was still a significant political

factor who would generally favor him,

and one who had been of valuable service

to the Republicans in 1912. He

therefore endorsed Daugherty for a seat in the

85. The two had met in November 1899 at

Richwood, Union County. In the immediate years their

relationship had been rather casual at

best. The Harding Papers contain only three letters from Daugh-

erty for the 1899-1911 period. At worst

Harding, as a pro-Foraker lieutenant, sometimes opposed

Daugherty politically.

86. Daugherty to Warren G. Harding,

November 16, 1912, January 13, 1913, Box 51, Warren G.

Harding Papers, Ohio Historical Society.

87. Daugherty to County Chairmen, November

7, 1912, Box 21, Phipps Papers.

88. Frank B. Willis and Simeon Fess,

both involved in United States congressional campaigns in

1912, are examples of those who

advocated reunion. See Gerald E. Ridinger, "The Political Career of

Frank B. Willis" (unpublished Ph.D.

dissertation, Department of History, The Ohio State University,

1957), 44; and John Lewis Nethers,

"Simeon D. Fess: Educator and Politician" (unpublished Ph.D.

dissertation, The Ohio State University,

1964), 139-140.

89. Columbus Week, May 3, 1913.

90. In fairness to Daugherty, however,

in 1913 such Progressive leaders as James Garfield or Arthur

Garford had no intention of returning to

Republicanism even if Daugherty were out of office. Hoyt

Landon Warner, Progressivism in Ohio,

1897-1917 (Columbus, 1964), 468. At one point, Daugherty hinted

at resignation but did not step down. Ohio

State Journal, February 13, 1914.

91. Warner, Progressivism, 471. See

also Russell, Blooming Grove, 245.

Harry M. Daugherty 171

United States senate in 1916. Even

Harding, however, could not help Daugherty

enough in the primary election for the

party's senatorial nomination. His setback

to Myron T. Herrick was so overwhelming

that Harding thought it meant "his

complete retirement."92 Out

of eighty-eight counties, Daugherty managed to win

only six--a block in south central Ohio.

Only in Fayette did he gain a convincing

victory.93 If it had not been

for the subtle endorsement of Harding and the un-

qualified backing of the Tafts'

Cincinnati Times-Star, his defeat would have reached

even more humiliating proportions.94

Daugherty blamed his poor showing on the

large sums of money that Herrick had

spent and on Republican presidential candi-

date Charles Evans Hughes' praising of

Herrick's French ambassadorship in the

Taft period. Too, Daugherty admitted

that the "Progressives, finding that they had

a good chance to get even with me, lined

up solidly behind Herrick . . . ." What

he did not say was that many Republicans

also refused to favor him because of

their opposition to the way that he had

run the party.95

Even though perturbed, Daugherty had no

thoughts of divorcing himself from

politics. Adversity had a vindictive

rather than a crushing effect upon him. If any-

thing, he was even more certain that

former Progressive leaders like James R. Gar-

field and Walter Brown must never play

any important role within the Republican

party.96 Daugherty also

became extremely antagonistic toward the wet Hamilton

County Republican organization which he

believed had contributed to his primary

defeat. In November Daugherty came out

strongly for prohibition in Ohio, partly

because of his personal grudge against

Rudolph K. (Rud) Hynicka and other

Hamilton county leaders--at least, that

was how Harding analyzed Daugherty's

motives.97

By late 1917 Daugherty expediently

joined with the personally dry ex-governor

Frank B. Willis in sponsoring state-wide

prohibition. This growing movement, he

predicted, would carry Ohio dry by more

than 50,000 in 1918.98 Daugherty was

not dry personally. "Nobody ever

charged me with being a crank on the proposi-

tion," he asserted, "for a man

can take a drink and yet be in favor of abolishing

the business." In championing the

movement at this time he intended not only

to punish his political adversaries but

also to reelect Willis to the governorship.

If he succeeded, he would have much to

say about presidential politics in Ohio

for 1920. Also, there was already a

rumor early in 1918 that if Harding were nomi-

nated to the vice-presidency, as

appeared possible, Willis, if elected, would appoint

Daugherty to Harding's unexpired term in

the Senate.99 Nothing would have pleased

Daugherty more.

The reported Daugherty-Willis accord

caused Harding some concern. He doubted

the wisdom of renominating the

previously defeated Willis. He also feared that

Daugherty's disdain for the party's

progressive and wet factions would disrupt his

92. Harding to Malcolm Jennings, August

26, 1916, Box 1, Malcolm Jennings Papers, Ohio His-

torical Society.

93. Ohio, Annual Report of the

Secretary of State, 1917, pp. 558-559.

94. Campaign clipping from Jewish

Review and Observer (Cleveland), July 28, 1916, Box 4, Harris

Collection. See also editorial,

Cincinnati Times-Star, July 24, 1916.

95. See, for example, Daugherty

to Simeon Fess, December 23, 1915, copy in Box 334, Series III,

Taft Papers.

96. Daugherty to Taft, August 18, 1916,

Box 35, Series III, ibid.

97. Harding to F. E. Scobey, December 4,

1916, Box 1, F. E. Scobey Papers, Ohio Historical Society.

98. Daugherty to Harding, May 31, 1918,

Box 85, Harding Papers. The Ohio dry referendum had

narrowly failed in the 1917 fall

election.

99. William Wood to Harding, February

23, 1918, Box 72, Harding Papers.

172

OHIO HISTORY

efforts to restore party harmony and

consequently would jeopardize his own re-

election, or a vice-presidential bid in

1920.100 Because of such growing differences,

a clash developed between Daugherty and

Harding in 1918 over the fundamental

issue of party control in Ohio.

Difficulties began to develop in early

1918 when Daugherty ignored Harding's

advice to reach a compromise with Rud

Hynicka and the Hamilton County organi-

zation over the prohibition issue.

Daugherty instead encouraged Willis "to make

no concessions to anybody."101 He

then warned Harding that Hynicka was conspir-

ing with former Progressive Walter Brown

to seek no less than complete control

of the party machinery. This

Progressive-wet alliance, according to Daugherty,

was already plotting to deliver the Ohio

delegation to Theodore Roosevelt in 1920.

"When that is done," he

prophesied, "they expect to elect United States Senators

and governors, and wipe the real

Republicans off the face of the earth."102

In the August primary Willis won the

gubernatorial nomination despite a trounc-

ing from Hamilton County. His victory

forecast a dry party platform and meant

a Daugherty-Willis takeover of most of

the party machinery.103 Daugherty's friend

Newton Fairbanks became the new

Republican state central committee chairman

and a Willis lieutenant, Edward

Fullington, was appointed chairman of the Re-

publican state executive committee. Only

the Harding-created state advisory com-

mittee, which had been formed in 1916 to

aid in the further reunification of the

party, remained undisturbed.

Daugherty's plans had to be modified,

however, when Willis had the misfortune

of being the only Republican candidate

not to win a state office in the November

election. Losing by only a 14,000

plurality, he suffered from a 16,500 deficit in

Hamilton County.104 Immediately

after the election, Daugherty wrote Harding, "I

suppose you learned the whole story of

the bolters' crimes. . . . Practically the

whole crime was committed in Cincinnati.

. . . Henceforth the fight in Ohio will

be against Hamilton county, and on that

issue the Republicans will never lose."105

Daugherty was now even more convinced

that Hamilton County leaders must not

play any significant part in the state

party's organizations.

Senator Harding did not share

Daugherty's conclusions. He believed that for

party success cooperation was essential

with Hamilton. "I am getting a number of

echoes of the Ohio political

atmosphere," he cautioned Daugherty, "and have

heard you no little discussed in such

revelations. . . ."106 Due to the outcry against

Daugherty's manipulations and because of

his own desire for party unity, Harding,

as chairman of the advisory committee,

decided to call for a joint meeting of that

body and the state central committee for

mid-December."107 He hoped to reactivate,

expand, and reorganize the advisory

committee and to include more Republicans

from Hamilton County.

100. Sinclair, Available Man, 103.

101. Daugherty to Frank B. Willis,

January 24, 1918, Box 6, Frank B. Willis Papers, Ohio Historical

Society. Hynicka was successor to Boss

George Cox.

102. Daugherty to Harding, June 3, 1918,

Box 85, Harding Papers.

103. Charles E. Hard to Harding, August

20, 1918, Box 367, ibid.

104. Ridinger, "Willis," 141.

Sole blame cannot be placed on Hamilton County. The attacks on

Willis' patriotism and his poor showing

as governor from 1914 to 1916 lost him a number of votes

throughout the state.

105. Daugherty to Harding, November 18,

1918, Box 85, Harding Papers.

106. Harding to Daugherty, November 23,

1918, ibid.

107. Harding to Hard, November 29, 1918,

Box 1, Charles E. Hard Papers, Ohio Historical Society.

See also Harding to N. H. Fairbanks, December 12, 1918, Box

1, Fairbanks Papers.

Harry M. Daugherty 173

His authority rested on the 1918 state

convention's endorsement of a revitalized

advisory organization.108 Harding,

at this time, seemed intent on weakening the

influence of the Daugherty-controlled

central committee by reorganizing the advi-

sory committee.

Daugherty, of course, strongly opposed

Harding's proposal and countered with

a warning that the party's real enemies,

the Walter Brown and Hamilton crowd

especially, wished to use the meeting

and the advisory committee as vehicles to

capture control of the party. He implied

that their plot included the debasement

of Harding as a political factor in

Ohio.109 Daugherty denied that ulterior motives

influenced his viewpoint; he cared only

for party success and the well-being of

friends like Harding and Willis.

Discounting any personal grudge against Hamilton

County Republicans, he retorted to

Harding: "I am not in the fertilizer business

and do not consider it profitable to

pursue or puncture dead horses." He did feel,

however, that since they had been

treacherous, he would never have confidence in

them nor permit their participation in

party affairs. He concluded with a word of

caution. If Hamilton County had a large

representation on the new advisory com-

mittee, it would put Harding in a bad

light with the rank and file of the party who

had supported the ticket and could also

invite a renewed wet-dry conflict.110

For his part, Harding doubted the

existence of a plot against himself, Daugherty,

or any Republican leader-at least one

that was inspired by Brown or Hynicka. He

sarcastically confessed to Daugherty

that he was perhaps too innocent to suspect all

the so-called schemes of those who had

favored the meeting. "And . . . I am glad

I am of such a mind," Harding

stated; "I should really dislike to think that there

isn't any sincerity or genuine interest

in anybody. . . ."111 He saw clearly that the

personal ambitions of Daugherty and his

friends, rather than those of Brown, were

the main obstacle to his own plans of

controlling a united party for 1920. Harding

confided to an associate that he would

take issue with Daugherty if he insisted

upon continuing his political

manipulations.112 To another friend, he said he had

told Daugherty that "some things he

was committed to could not be."113 Harding,

in turn, had already been informed by

Hard that "we are dealing with a lot of very

thorough gentlemen [Daugherty, Herbert

Morrow, and Fairbanks], who are cold of

blood, who know what they want, and they

are going to get it if they can."114

Chairman of the central committee

Fairbanks requested Harding to postpone

the joint advisory-central committee

meeting until after the organization of the

state legislature in January. This

gesture perturbed Harding, especially when

Daugherty indicated that he and

Fairbanks must have a hand in the selection of

the advisory committee's membership.115

More disturbing was Daugherty's intima-

tion that resistance might invite an

opposition candidate for Harding's seat in the

108. Harding to Fairbanks, November 29,