Ohio History Journal

MARIAN J. MORTON

Homes for Poverty's Children:

Cleveland's Orphanages, 1851-1933

Orphanages were first and foremost

responses to the poverty of

children. Although historians disagree

over whether orphanage

founders and other child-savers were

villainous, saintly, or neither,

there is little disagreement that the

children saved were poor. When

this becomes the focus of the story,

orphans appear less as victims of

middle-class attempts to control or

uplift them than as victims of

poverty; orphanages emerge less as

punitive or ameliorative institu-

tions than as poorhouses for children,

and a history of Cleveland's

orphans and orphanages is less about the

struggle to restore social

order or evangelize the masses than

about the persistence of poverty in

urban America.1

Today Cleveland's three major child-care

facilities are residential

treatment centers which provide

psychiatric services for children with

emotional or behavioral problems. These

same facilities, from their late

nineteenth-century beginnings to the

Great Depression, however, were

Marian J. Morton is Professor of History

at John Carroll University.

1. Historians critical of child-savers

include the following: David J. Rothman, The

Discovery of Asylum: Order and

Disorder in the Early Republic (Boston,

1980); Steven

L. Schossman, Love and tile American

Delinquent: The Theory and Practice of

"Progressive" Juvenile

Justice, 1825-1920 (Chicago, 1977);

Anthony M. Platt, The Child

Savers: The Invention of Delinquency (Chicago, 1977); Ellen Ryerson, The Best-Laid

Plans: America's Juvenile Court

Experiment (New York, 1978), and

Michael B. Katz,

Poverty and Policy in American

History (New York, London, 1983) and In

the Shadow

of the Poorhouse: A Social History of

Welfare in America (New York, 1986).

More

positive evaluations include Susan

Tiffin, In Whose Best Interest: Child Welfare Reform

in the Progressive Era (Westport, Conn., 1982); Robert H. Bremner, "Other

People's

Children," Journal of Social

History, 16 (Spring, 1983), 83-104; Michael W. Sherraden

and Susan Whitelaw Downs, "The

Orphan Asylum in the Nineteenth Century," Social

Service Review, 57 (June, 1983), 272-90, and Peter L. Tyor and Jamil S.

Zainaldin,

"Asylum and Society: An Approach to

Institutional Change, Journal of Social History,

13 (Fall, 1979), 23-48. A sensitive and

balanced portrait of child-savers and child-saving

institutions is provided by LeRoy Ashby,

Saving the Waifs: Reformers and Dependent

Children, 1890-1917 (Philadelphia, 1984). An excellent review of the

literature on

child-saving is Clarke A. Chambers,

"Toward a Redefinition of Welfare History,"

Journal of American History, 73 (September, 1986), 416-18.

6 OHIO HISTORY

orphanages which provided shelter for

poor children: the Cleveland

Orphan Asylum (founded in 1852 and

renamed in 1875 the Cleveland

Protestant Orphan Asylum), which is now

Beech Brook; St. Mary's

Female Asylum (1851) and St. Joseph's

Orphan Asylum (1863), run by

the Ladies of the Sacred Heart of Mary,

and St. Vincent's Asylum

(1853) under the direction of the

Sisters of Charity, now merged as

Parmadale; and the Jewish Orphan Asylum

(1869), now Bellefaire,

founded by the Independent Order of

B'nai B'rith for the children of

Jewish Civil War veterans of Ohio and

surrounding states.2

During the period of the orphanages'

foundings, Cleveland exempli-

fied both the promises of wealth and the

risks of poverty characteristic

of nineteenth-century America. During

the Civil War the city began its

rapid transformation from a small

commercial village to an industrial

metropolis. Cleveland's established

merchants and industrialists built

their magnificent mansions east on

Euclid Avenue, migrating out from

the heart of the city where imposing

hotels and commercial buildings

had been newly built on the Public

Square.3

The booming economy also attracted

thousands of newcomers from

the countryside and from Europe to labor

in the city's foundries, sail its

lake vessels, and build its railroads.

Rapid population growth and the

incursion of railroads and factories

into poorer neighborhoods, how-

ever, caused overcrowding and heightened

the possibilities of fatal or

crippling disease. Migrants often

arrived with little money and few job

skills that would be useful in the city.

Employment, even for skilled

workmen, was often sporadic. Cleveland

also suffered from the

economic downturns experienced by the

rest of the country. But the

bank failures of the mid-1850s and the

railroad overspeculation of the

1870s caused the hardest times for

Cleveland's working people.4

2. The founding of the Cleveland

Protestant Orphan Asylum is described in Mike

McTighe, "Leading Men, True Women,

Protestant Churches, and the Shape of

Antebellum Benevolence," in David

D. Van Tassel and John J. Grabowski, eds.,

Cleveland: A Tradition of Reform, (Kent, Ohio, 1985), 20-24. On the Catholic orphan-

ages, see Michael J. Hynes, History

of the Diocese of Cleveland: Origin and Growth

(Cleveland, 1953), 90-94, and Donald P.

Gavin, In All Things Charity: A History of the

Sisters of Charity of St. Augustine,

Cleveland, Ohio, 1851-1954 (Milwaukee,

1955),

19-36; and on the Jewish Orphan Asylum,

see Gary Polster, "A Member of the Herd:

Growing Up in the Cleveland Jewish

Orphan Asylum, 1868-1919" (Ph.D. Dissertation,

Case Western Reserve University, 1984),

and Michael Sharlitt, As I Remember: The

Home in My Heart (Cleveland, 1959).

3. Edmund H. Chapman, Cleveland:

Village to Metropolis (Cleveland, 1981),

97-150.

4. William Ganson Rose, Cleveland:

The Making of a City (Cleveland, 1950), 230.

363.

Homes for Poverty's Children 7

Because there was no social insurance,

family was the only safe-

guard against disaster. But family

obligations were loosened in the city

where the traditional constraints of

church and village were missing.

And when family resources were gone,

individuals-sometimes adults

and often children-fell ready victims to

poverty.5

Americans had traditionally aided the

poor with outdoor relief, the

distribution of food, clothing, or fuel

by the local government and by

private organizations. By the

mid-nineteenth century, however, many

philanthropists and public officials had

come to believe that outdoor

relief actually encouraged pauperism and

that the poor might be better

cared for in institutions where job

skills, the love of labor, and other

middle-class virtues might be taught,

thus preventing further depen-

dence.6

Accordingly, both the private and public

sectors expanded existing

institutions or opened new ones for the

dependent poor. In 1856 the

city of Cleveland opened an enlarged

poorhouse or Infirmary, which

housed the ill, insane, and aged, as

well as those who were simply

poverty-stricken. In 1867 the city's

oldest private relief organization,

the Western Seamen's Friend Society,

founded the Bethel Union,

which opened two facilities for the

homeless. Both were sustained

financially by funds from local

Protestant churches, and their purpose

was to convert as well as to shelter the

poor and needy.7

The private orphanages were an outgrowth

of the conviction that

dependent children and adults should not

be housed together in an

undifferentiated facility. Although most

Ohio counties eventually

administered county children's homes, Cuyahoga

County did not, and

the city of Cleveland, therefore,

continued to be responsible for

dependent children. In 1856 the

Infirmary had about 25 school-aged

children in residence who not only

shared the building with the

violently insane and the syphilitic, but

who received only four months

of schooling during the year because no

teacher was available. Like the

common schools, therefore, orphanages

were intended to be institu-

tions exclusively for children, with a

mission derived both from their

sectarian origins and from the poverty

of their inmates.8

5. Chambers, "Redefinition of

Welfare History," 421-22.

6. According to Rothman, The

Discovery of Asylum, 185, institutionalization "dom-

inated the public response to poverty."

See also Katz, Poverty and Policy, 55-89, and In

the Shadow of the Poorhouse, 3-35.

7. Rose, Cleveland, 230; Florence

T. Waite, A Warm Friendfor the Spirit: A History

of the Family Service Association of

Cleveland and its Forebears, 1830-1952 (Cleveland,

1960), 3-10.

8. Homer Folks, The Care of

Destitute, Neglected, and Delinquent Children

8 OHIO HISTORY

Most children sheltered in Cleveland's

orphanages were orphaned

by the poverty of a single parent, not

by the death of both; that is, they

were "half orphans." Most

common perhaps was the plight of the

widowed or deserted mother forced to

give up her children because she

could not support them herself: for

example, the nine-year old Irish

boy, whose father was "killed on

the R.R. [railroad] and [whose]

mother bound him over" to St.

Vincent's until his eighteenth birthday

with the hope that he would learn a

trade. There were few jobs for

working-class women besides domestic

service, which paid little and

did not allow a woman to live at home

with her children. Many

widowers, on the other hand, were

unable to both provide a home for

their children and earn a living.9

Many orphans were the children of the

city's new arrivals from the

country or Europe, whose Old World

customs or rural habits left them

unable to cope with American urban

life. The Protestant Orphan

Asylum annual report of 1857 claimed

orphans "from every part of the

Old World." The register of St.

Mary's noted children from Ireland,

Germany, and England, and the Jewish

Orphan Asylum, from Russia

and Austria.10

Illness or accidents on the job also

impoverished families by causing

hours lost on the job and consequent

loss of wages at a time when

working-class men probably earned

barely subsistence wages. A

cholera epidemic in 1849 provided the

immediate impetus for the

founding of the Protestant Orphan

Asylum.11

At best, employment for Cleveland's

working class might be season-

al or intermittent. Construction

workers and longshoremen, for exam-

ple, were laid off in the winter,

leaving them unable to provide for their

(London, 1902), 73-81; Robert H.

Bremner, ed., Children and Youth in America: A

Documentary History, Vol. I, (Cambridge, Mass., 1970), 631-32. The local

reference is

City of Cleveland, Annual Report,

1856 (Cleveland, 1856), 38.

9. The predominance of

"half-orphans" has been noted as early as the 1870s: see

Rachel B. Marks, "Institutions for

Dependent and Neglected Children: Histories,

Nineteenth-Century Statistics and

Recurrent Goals" in Donnell M. Pappenfort et al.,

eds., Social Policy and the

Institution (Chicago. 1973), 32. The local reference is to St.

Vincent's Asylum Registry, Book A,

Cleveland Catholic Diocesan Archives, Cleveland,

Ohio, n.p.

10. Cleveland Orphan Asylum, Annual

Report, 1857 (Cleveland, 1857), 4. (Hereinaf-

ter this orphanage will be referred to

by its later name, the Cleveland Protestant Orphan

Asylum); St. Mary's Female Asylum

[labeled St. Joseph's], et passim, Cleveland

Catholic Diocesan Archives; Jewish

Orphan Asylum Annual Reports, 1869-1900 et

passim. (These

papers are at the Western Reserve Historical Society under the

institution's later name, Bellefaire, MS

3665.)

11. Cleveland Herald, November

12, 1849, n.p. in Scrapbook 1, at Beech Brook

(formerly the Cleveland Protestant

Orphan Asylum), Chagrin Falls, Ohio.

|

Homes for Poverty's Children 9 |

|

|

|

families or compelling them to migrate elsewhere in search of employ- ment. The Protestant Orphan Asylum annual report in 1857 noted: "Many now under the care of this Society were cast upon its charity by mere sojourners whose children have been left at the Infirmary." "Father on the lake," often commented the register of St. Joseph's, suggesting that the mother was left to fend for herself.12 The difficulties of earning a steady and substantial living were compounded by the recessions and depressions which occurred in each of the last three decades of the nineteenth-century. The depression of 1893 was the worst the country had suffered thus far and strained the relief capacities of both private and public agencies in Cleveland and other cities. The depression was felt immediately by all institutions

12. Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum, Annual Report, 1857 (Cleveland, 1857), 4; St. Joseph's Admissions Book, 1884-1894, Cleveland Catholic Diocesan Archives. Sherraden and Downs, "The Orphan Asylum," pinpoints transience as the most common characteristic of orphans' families. |

10 OHIO HISTORY

which cared for dependent persons,

especially for children, as record-

ed in the Jewish Orphan Asylum

superintendent's report from 1893:

"The business crisis, sweeping like

a fierce storm over our country

through its length and breadth, has made

its influence felt also in the

affairs of our Asylum. Since its

existence we have not received so

many new inmates [121] as in the year

past." St. Mary's register

includes this vignette from 1893:

"Father dead, Mother is living; later

went to the Poor House at

Cleveland."13

Because nineteenth-century Americans

blamed poverty on individ-

ual vice or immorality, they readily

assumed that poor adults were

neglectful and poor children were

ill-behaved. Dependency and delin-

quency were synonymous for all practical

purposes: the Protestant

Orphan Asylum commented in 1880 that

"the greater proportion [of

children admitted] have come from homes

of destitution and neglect-

innocent sufferers from parental

mismanagement or wrongdoing." 14

The Cleveland Humane Society, the city's

chief child-placing agen-

cy, was empowered to remove a child from

its parents' home to an

institution if they were judged

neglectful or abusive, and some parents

were. The Humane Society sent to the

Protestant Orphan Asylum a

boy who had been taken to the police

station by his mother and

stepfather "for the purpose of

inducing the Court to send him to the

House of Corrections," the local

detention facility. A few parents

simply abandoned their offspring, as did

the "unnatural mother" who

in 1854 left her three-year-old son in a

priest's parlor.15 Many parents

were described-probably accurately-as

"drunkards" or "intem-

perate."

Orphanages' policies and practices

indicate their mission to relieve

and remedy poverty. The Protestant

Orphan Asylum took in children

from the city Infirmary and received

some funds from the city,

acknowledging the orphanage's poor

relief responsibilities. Although

neither the Catholic nor the Jewish

institutions got public aid, they

were supported by the Catholic Diocese

and the B'nai B'rith, which

were welfare agencies for those

denominations. The poor relief role of

the Jewish Orphan Asylum was implicit in

its by-laws, which required

13. Bellefaire, MS 3665, Jewish Orphan

Asylum, Annual Report, 1893, 23, Container

15; St. Joseph's Registry, 1883-1904,

n.p., Cleveland Catholic Diocesan Archives. On

the impact of the Depression of 1893 on

public and private relief agencies, see Katz, In

the Shadow, 147-50.

14. Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum, Annual

Report, 1880 (Cleveland, 1880), 6.

15. Children's Services, MS 4020,

Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland

Humane Society, Scrapbook, Minutes, Nov.

26, 1881, Container 1; St. Mary's Registry

Book [labeled St. Joseph's] 1854, n.p.,

Cleveland Catholic Diocesan Archives.

Homes for Poverty's Children 11

that no orphans could be received

"who have adequate means of

support, nor any half orphan whose

living parent is able to support the

same."16

Also indicative of this role was the

orphanages' practice in their early

decades of "placing out" or

indenturing children to families which

were supposed to teach the child a trade

or provide some formal

education in return for help in the

household. Indenture had been a

traditional American way of dealing with

the children of the poor since

the colonial period and was routinely

used by the Infirmary. A printed

circular from the Protestant Orphan

Asylum advertised: "Forty bright

attractive boys from one month to 8

years of age for whom homes are

desired. We also have a few nice girls

under ten and a few baby

girls." 17

The orphanages' primary official goal

was religious instruction and

conversion. Sectarian rivalries were an

important stimulus for the

founding and maintenance of the

orphanages, as each denomination

strove to restore or convert children to

its own faith. But because most

Americans identified poverty with moral

weakness or vice, religious

conversion was seen not only as a way of

saving souls but as a logical

remedy for dependence. Religious

services were daily and mandatory:

"Each day shall begin and end with

worship," noted the Protestant

Orphan Asylum. Children at the Jewish

Orphan Asylum were taught

Hebrew and Jewish history. The registers

of the Catholic orphanages

noted whether the parents were

Protestant or Catholic and when the

child made first communion.18

Orphanage administrators also saw the

practical need to provide

children with a common school education

and especially vocational

training. Children from the Protestant

Orphan Asylum and the Jewish

16. "The Cleveland Protestant

Orphan Asylum, An Outline History," n.d., n.p. at

Beech Brook; Bellefaire, MS. 3665,

Bylaws of the Jewish Orphan Asylum, Container 1,

Folder 1. The public funding of private

child-care institutions is noted also in Folks, The

Care of Destitute, and Bremner, ed., Children and Youth, Vol. 1,

663-64.

17. Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum

annual reports note such indentures through

the 1870s; an indenture agreement is

contained in Scrapbook 2 at Beech Brook. The

advertisement is found in

"Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum," Vertical file,

Western Reserve Historical Society. On

the custom of indenturing pauper children, see

Folks, The Care of Destitute, 39-41;

Bremner, Children and Youth, Vol. 1, 631-46;

Michael Grossberg, Governing the

Hearth: Law and the Family in Nineteenth-Century

America (Chapel Hill, 1985), 266-67. Tyor and Zainaldin,

"Asylum and Society," 27-30,

discuss similar placement practices at

the Temporary Home for the Indigent.

18. Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum, Annual

Report, 1875 (Cleveland, 1875), 22;

Bellefaire, MS 3665, Jewish Orphan

Asylum, Annual Report, 1874, 15, Container 1,

Folder 1; St. Joseph's Registry Book 1,

Cleveland Catholic Diocesan Archives, et

passim.

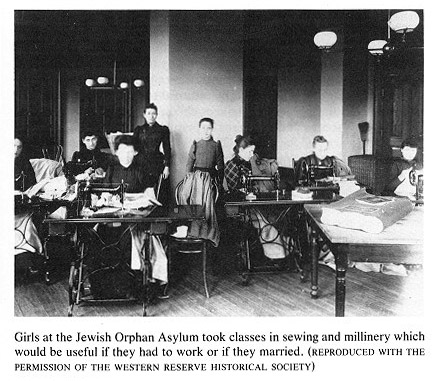

12 OHIO HISTORY

Orphan Asylum attended classes in nearby

public schools. Job training

was acquired in the orphanage either by

attending classes or, probably

most often, by maintaining the buildings

and grounds of the orphanage

itself. And the intention was to teach

more than skills, as the 1869

Jewish Orphan Asylum report noted:

"Love of industry, aversion to

idleness, are implanted into their young

hearts, being practically taught

by giving the larger inmates some light

work to perform before or after

school; the girls to assist in every

branch of the household, and the

boys to keep the premises in order, and

to cultivate our vegetable

garden."19

Parents, too, saw orphanages as

solutions to poverty-their own-

and often committed their children

themselves, sometimes placing

them up for adoption but far more often

relinquishing control only

temporarily until the family could get

back on its feet. Orphanage

registers often contain entries such as

this from St. Mary's (1854) about

an eight-year-old girl: "both

[parents] living but could not keep the

child on account of their difficult

position." The child returned to her

parents after a brief stay.20

Orphanages sometimes asked parents or

other family members to

pay a portion of the child's board, but

it is not clear that they did. The

institutions thus became refuges where

poor children could be fed,

sheltered, clothed, and educated at

little or no expense to their parents.

Orphanages tried to be homes, not

institutions, but life in these large

congregate facilities did not encourage

individuality or spontaneity. In

1900 the Jewish Orphan Asylum, the

largest of the institutions,

sheltered about 500 children; St.

Vincent's about 300, and the Protes-

tant Orphan Asylum close to 100. The

Jewish Orphan Asylum super-

visor boasted that his orphanage did not

turn out "machine children,"

but obviously regimentation was

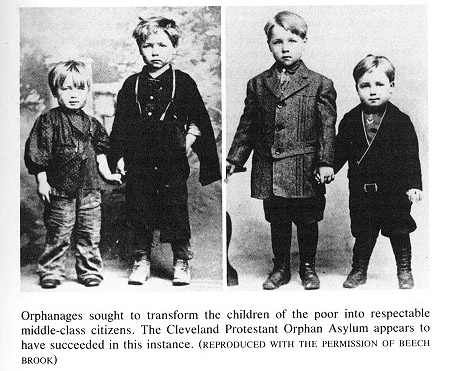

imperative.21 The orphanages encour-

aged organized games and sports on

adjoining playgrounds, and the

children wore uniform clothing in

keeping with the theory that they

needed discipline. Moreover, all the

institutions operated on slender

budgets which did not allow for

luxuries. Nor would self-indulgence or

19. Bellefaire, MS 3665, Jewish Orphan

Asylum, Annual Report, 1869, 15, Contain-

er 15.

20. St. Mary's Registry Book [labeled

St. Joseph's] n.p., Cleveland Catholic Dioce-

san Archives. Katz describes this use of

orphanages in Poverty and Policy in American

History, 18-56, and In the Shadow, 113-45.

21. Bellefaire, MS 3665, Jewish Orphan

Asylum, Annual Report, 1889, 44, Container

16; Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum, Annual

Report, 1894 (Cleveland, 1894), 5;

"St. Vincent's Orphan Asylum,

1881-1900," in folder, "St. Vincent's Orphanage", n.p.,

Mt. St. Augustine Archives, Richfield,

Ohio. These were standard sizes for orphanages

nationally, according to Marks,

"Institutions for Dependent," 37.

|

Homes for Poverty's Children 13 |

|

|

|

self-expression have been considered appropriate, given the orphan- ages' mission and clientele. It is difficult to know how the children themselves felt. Both the Jewish Orphan Asylum and the Protestant Orphan Asylum published glowing accounts from their "graduates," but these should be read with caution. Deeds speak louder than words in an annual report. A few adventurous children-more boys than girls-"ran away in the night when everyone was asleep," perhaps in desperate, homesick search for parents or siblings. One mother removed her children from St. Mary's and placed them with friends, for "the children were very lonely, and she feared they would worry too much."22 Every orphan- age annual report recorded at least one death, for childhood diseases like measles and whooping cough could be fatal.

22. According to Jay Mechling, "Oral Evidence and the History of American Children's Lives," Journal of American History, 74 (September, 1987), 579, "Children remain the last underclass to have their history written from their point of view." Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum annual reports during the 1870s carry letters from |

14 OHIO HISTORY

The vast majority of children, however,

did stay until they were

discharged by the institution. The stays

lasted sometimes only a few

days or weeks but most often months and

years. The Protestant

Orphan Asylum from the first advocated

only temporary institutional-

ization, but "temporary" might

mean at least a year until a foster home

could be found or the child could be

returned to family or friends. St.

Mary's and St. Joseph's routinely kept

children four to five years, but

St. Vincent's for much briefer periods,

perhaps because there was less

room or more demand for service. The

Jewish Orphan Asylum kept the

children sometimes as long as eight or

nine years, possibly because it

was more difficult to keep in touch with

their out-of-town families.23

Yet if bleak and regimented, life in

these institutions may have seemed

better to these children or to their

parents than the nineteenth-century

alternatives: the Infirmary or a life of

destitution.

By the early years of the

twentieth-century, Cleveland had under-

gone dramatic and decisive changes.

Reflecting the national trend, the

city's economy had completed the shift

to heavy industry, particularly

the manufacture of finished iron and

steel products. Burgeoning

prosperity allowed Cleveland's

established families to continue a

migration out of the central city, which

by the 1920s would reach the

neighboring suburbs, and to generously

endow the city's lasting

monuments to culture, the Cleveland

Museum of Art and the Cleveland

Orchestra.

This wealth was not evenly distributed.

Responding to the impera-

tives of greater industrialization, the

work force was less skilled and

even more vulnerable to unemployment and

economic crisis. The

multiplication of the population by more

than twenty-fold from 1850 to

1900 indicated a high degree of

transience. Furthermore, in 1910 almost

75 percent of Clevelanders were either

foreign-born or the children of

foreign-born parents. These people,

drawn increasingly from south-

eastern Europe and clustered in

congested and unwholesome ghettos,

faced greater cultural obstacles to

economic success or assimilation

than had earlier immigrants.24

former inmates and the families with

whom they had been placed, and the Jewish Orphan

Asylum published the Jewish Orphan

Asylum Magazine, 1903 ff, in Bellefaire, MS 3665,

Containers 16 and 17. The specific

reference is to St. Joseph's Orphan Asylum,

1883-1894, n.p., Cleveland Catholic

Diocesan Archives.

23. This can be calculated by comparing

the number admitted with the number

released in the Cleveland Protestant

Orphan Asylum annual reports. The registers of the

Catholic institutions noted the length

of stay, as did the Jewish Orphan Asylum annual

reports.

24. Cleveland Federation for Charity and

Philanthropy, The Social Year Book: The

Human Problems and Resources of

Cleveland (Cleveland, 1913), 8.

Homes for Poverty's Children 15

Changes in both the private and the

public relief efforts acknowl-

edged the growing scope and complexity

of this urban poverty. Private

relief efforts continued to be crucial,

as suggested by the establishment

in 1913 of a federated charity

organization, the Federation for Charity

and Philanthropy, to coordinate the

activities of the proliferating

voluntary agencies and institutions.

Many of these shared the redis-

covered belief that dependence was best

cured by the efficient distri-

bution of outdoor relief, not by

institutionalization. An example of this

changed strategy was Associated

Charities, offspring of the Bethel

Union, whose goal was no longer to

provide shelter for the dependent,

but "to provide outdoor relief ...

and to rehabilitate needy families."25

Public relief activities also reflected

this trend. The city relied

increasingly upon outdoor relief. The

former Infirmary by 1910 housed

only the old and chronically ill.

Policies regarding the care for

dependent children changed as well.

The 1909 White House Conference on

Dependent Children signaled an

increased willingness on the part of

public officials to assume respon-

sibility for child welfare and stressed

that "home life" was far better

for children than institutional life.

These new directions were embodied

in a 1913 Ohio mothers' pension law

which provided widows or

deserted mothers with a stipend so that

they could care for their

children in their own homes rather than

place them in an orphanage.26

The orphanages were compelled to adapt

to these trends although

they did so only gradually. They began

by trying to redefine their

clientele. For if children belonged in their

own homes and their poverty

was a public responsibility, who

belonged in a private institution?

Anticipating the future psychiatric

orientation of the orphanages, the

Protestant Orphan Asylum by the end of

the 1920s developed this

answer: that their clientele would be

"problem cases" and "unsocial"

children who would not fit into a

private home until a stay in the

orphanage had helped them to unravel

their "mental snarls." The other

orphanages' records also began to note

children's behavior problems.27

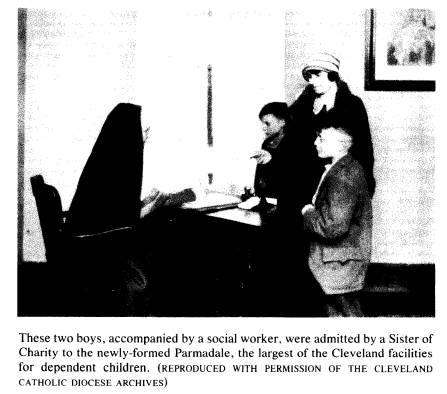

In the 1920s the orphanages moved out of

the central city into the

suburbs and replaced their congregate

housing with cottages more

25. Ibid., 39.

26. Bremner, Children and Youth, Vol.

11, (Cambridge, Mass., 1972) vii-viii, and

"Other People's Children,"

88-89.

27. Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum, Annual

Report, 1926 1929 (Cleveland,

1929), 47; St. Joseph's Register,

1929-1942 et passim. Michael Sharlitt, Superintendent of

Bellefaire, made a distinction between

its earlier inmates who were "biological" or

"sociological orphans" and its

current inmates who were "psychological orphans" in

Bellefaire, MS 3665, Bellefaire Annual

Reports, 1933-34, n.p., Container 16, Folder 1.

|

16 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

suggestive of "home life" and more conducive to individual psycho- logical treatment. The facilities sheltered fewer children and were able to allow a more flexible regimen within their walls and more opportu- nities for recreation outside. Not coincidentally, the orphanages even- tually assumed new names, suggestive of their rural and noninstitutional settings: the Catholic institutions merged to become Parmadale, the Jewish Orphan Asylum became Bellefaire, and the Protestant Orphan Asylum was rechristened Beech Brook. Orphanages also modified some of their discharge practices. As early as 1912, for example, the Protestant Orphan Asylum noted an increase in the number of children given "temporary care" and returned to their parents after a family "emergency" had been solved, maintaining that this was the asylum's way to help "re-establish a home." All orphan- ages reported few adoptions, and when the return of the child to its own home seemed impossible, it was placed in a foster home. The Catholic orphanages and the Jewish Orphan Asylum, however, were slow to relinquish children to foster homes, probably because of the |

Homes for Poverty's Children 17

difficulty in finding an appropriate

Catholic or Jewish foster family. In

1929 the average stay at the Jewish

Orphan Asylum was still 4.2

years.28

All orphanages retained their religious

impetus and character, for

they had vital spiritual and financial

ties to their particular denomina-

tions. The Protestant Orphan Asylum's

1917 annual report, for exam-

ple, described the orphanage as "a

temporary home for dependent

children, a stopping place on their way

from homes of wretchedness

and sin to those of Christian

influence." The Jewish Orphan Asylum

emphasized the "teaching of the

history and the religion of our people

with the end in view that our children

be thoroughly imbued with the

spirit of Jewishness, which for years to

come may be their guide

through life."29

All continued to teach the children both

the habit and the virtue of

labor. Even after its move to the

country the Protestant Orphan

Asylum provided the children with

"various ways of earning money.

[The children's] regular household

duties they do, of course, without

compensation, but there are extra jobs

for which they are paid, such as

washing windows, shoveling snow,

carrying coal for the kitchen

range." The wages were to be

secured in the orphanage savings

bank.30

The slowness to change practices is

partially explained by the fact

that the orphanages still housed poor

children. Their poverty is

apparent in the records of the separate

orphanages but even more

noticeable in large-scale studies

conducted by the Cleveland Welfare

Federation and the Cleveland Children's

Bureau. The immediate

impetus for the Bureau's establishment

was a survey which showed

that orphans, as in the

nineteenth-century, had parents who were using

the orphanages as temporary shelters for

their children: 91 percent of

the children in Cleveland orphanages

during 1915-1919 had at least one

surviving parent and 66 percent returned

to parents or relatives. The

Protestant Orphan Asylum claimed in 1913

alone to have been beseiged

by 252 requests from parents to take

care of their children.31

28. Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum, Annual

Report, 1912 (Cleveland, 1912),

16-17; Bellefaire, MS 3665, "A

study of Intake Policies at Bellefaire," 2, Container 19,

Folder 1.

29. Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum, AnnualReport,

1917 (Cleveland, 1917), 10;

Bellefaire, MS 3665, Jewish Orphan

Asylum, Annual Report, 1907, 41, Container 15.

30. Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum, Annual

Report, 1926-29 (Cleveland,

1929), 47.

31. Children's Services, MS 4020,

Western Reserve Historical Society, U.S.

Children's Bureau, "The Children's

Bureau of Cleveland and Its Relation to Other

Child-Welfare Agencies,"

(Washington D.C., 1927), 19, Container 6; Cleveland Protes-

18 OHIO HISTORY

Because this practice ran counter to the

prevailing belief that

children were best raised within

families, the Bureau was supposed to

screen the requests for placement by

agencies and particularly by

parents, such as this one: "A

so-called widow with three children was

referred for study from an institution.

It was planned the children

would be kept temporarily during the

summer, to return to the woman

in the fall, giving her an opportunity

to catch up financially." Investi-

gation by the Bureau revealed, however,

that she had remarried and

that she and her second husband were

suspected of "neglect and

immorality;" after a mental test,

she was sentenced to the Marysville

Reformatory.32

As in previous years, the parents of

orphans were often new

immigrants to the United States.

Orphanage registers noted the greater

numbers of southeastern European

immigrants. The Protestant Orphan

Asylum claimed in 1919 that of its 111

new client families, only 44 were

"American." The records

of St. Vincent's and the Jewish Orphan

Asylum noted children of Italian,

Polish, Lithuanian, Hungarian,

Russian and Roumanian backgrounds. To

St. Joseph's, for example,

came a Russian widow, who "being

obliged to work out," wanted the

asylum to keep her child; so recently

had she arrived that she "needed

an interpreter" to make her

request.33 Despite the growing number of

black migrants from the South, however, no

private child-care institu-

tion in the city took black children

during this period.34

Disease still killed and disabled

parents. The nineteenth-century

cholera epidemics had a

twentieth-century counterpart in the great flu

epidemic of 1918. A Children's Bureau

study of institutionalized

children in 1922-25 listed illness or

physical disability as the condition

which most contributed to children's

dependency.35

tant Orphan Asylum, Annual Report,

1913 (Cleveland, 1913), 14.

32. Children's Services, MS 4020, First

Annual Report of the Children's Bureau,

1922, 1-2, Container 4, Folder 50.

33. Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum, Annual

Report, 1919 (Cleveland, 1919), 10;

St. Joseph's Register, 1884-1904, n.p.,

Cleveland Catholic Diocesan Archives.

34. U.S. Government Publishing Office, Children

Under Institutional Care, 1923

(Washington, D.C., 1927), 106-09,

indicates that Cleveland institutions took only white

children. This is substantiated by

Children's Services, MS 4020, Minutes, Cleveland

Humane Society, April 10, 1931,

Container 3, Folder 41. A memo from the Protestant

and nonsectarian child-care agencies to

the Children's Council of the Welfare Federa-

tion, May 29, 1945, 6, Federation for

Community Planning, MS 3788, Western Reserve

Historical Society, Container 48, Folder

1166, indicates that this was still the practice at

that date although the Catholic

institutions had "no policy of exclusion because of

color."

35. Children's Services, MS 4020, U.S.

Children's Bureau, "The Children's Bureau

of Cleveland," 11.

Homes for Poverty's Children 19

"Mental disability,"

interestingly, ranked fourth in this list, and

orphanage records also stated that

mental illness frequently incapaci-

tated parents. The 1923 Jewish Orphan

Asylum report, for example,

described a "Mother in state

institution" and a "Mother incompetent,

supposed to be suffering from

melancholia."36 Perhaps culture shock

drove these new immigrants mad.

More likely, however, these parents were

victims of the current

vogue for IQ and personality testing and

for institutionalizing those

diagnosed as mentally incompetent or

"feeble-minded." The practical

implications of this analysis and

treatment for both children and

parents are illustrated in this case

study from the Children's Bureau:

"M[an] died Feb. 1921, W[oman]

works in rooming-house on 30th and

Superior and is feeble-minded. Sarah, 7,

and William, 5, are both in

Cleveland Protestant Orphanage. Sarah is

peculiar ... William is sub-

normal, cannot stay with other

children."37

These diagnoses were simply a more

"modern" way of describing

the delinquency and neglect earlier

associated with poverty. By the

early twentieth-century this association

had been reinforced by the

cultural and religious differences

between the southeastern European

immigrants and orphanage administrators

and staff.

Some parents did abuse and neglect their

children. For example, the

Children's Bureau and the Humane Society

struggled together to solve

cases like this: "W[ife] ran away,

M[an] wanted children placed. Case

was in court; W was accused by M of

drinking. M and W tried living

together again, just had a shack and no

stove and W refused to stay

there. M was brought in later for

contributing to delinquency of a

niece." Or, from the Jewish Orphan

Asylum 1915 report, "Father

deserted wife and four children October

22. Mother found very untidy,

backward, and incompetent ... Plan to

send children to the Orphan

Home at that time was met with

resistance."38

Poverty, on the other hand, received

little emphasis in the Children's

Bureau study: "inadequate

income" ranked as only the fifth largest

contributor to child dependence.39 This

does not mean that institution-

36. Ibid.; Bellefaire, MS 3665,

Jewish Orphan Asylum, Annual Report, 1923, 66-67,

Container 16.

37. Children's Services, MS 4020,

Minutes of the committee of the Children's Bureau

and the Humane Society, undated but

mid-1920s, Container 4, Folder 50. See also Katz,

In the Shadow, 182-86, on eugenics and feeblemindedness as means of

diagnosing and

treating dependence.

38. Children's Services, MS 4020,

Minutes of the committee of the Children's Bureau

and the Humane Society, undated but

mid-1920s, Container 4, Folder 50: Bellefaire, MS

3665, Jewish Orphan Asylum, Annual

Report, 1925, 67, Container 15.

39. Children's Services, MS 4020, U.S.

Children's Bureau, "The Children's Bureau

20 OHIO HISTORY

alized children were no longer poor, but

that child-care workers were

reluctant to recognize the existence or

disruptive impact of poverty.

The mothers' pension law of 1913 was

supposed to have eliminated the

institutionalization of dependent

children, although federal census

figures show that in 1923 more dependent

children were cared for in

institutions than by mothers' pensions.

Reaffirming what had never-

theless become the accepted position,

the executive secretary of the

Humane Society in 1927 claimed that

"Poverty in itself does not now

constitute cause for removal of children

from their parents."40

Even during the much-vaunted prosperity

of the 1920s, however,

there were plenty of impoverished

Americans, especially in a heavy-

industry town such as Cleveland. For

example, although the Children's

Bureau survey maintained that

"unemployment due to industrial

depression did not appear as an acute

problem in the dependency of

these children," it did concede:

"Possibly the long period of unem-

ployment, which began in 1920 and lasted

into 1922 in Cleveland,

started in these families the

disintegrating forces reflected in ill health,

desertion, and the need of the mother to

go to work." Possibly indeed.

Poverty was in fact implicit in the many

referrals to the orphanages

from Associated Charities and other

relief agencies, in the dispropor-

tionate numbers of "new

immigrant" parents noted, and in the

preponderance of mothers' requests for

placement for their children

since a widowed, deserted, or unwed

mother had as few financial

resources in the twentieth-century as

she had in the nineteenth.41

By 1929 when the Depression officially

began, the poverty of the

city's orphans could no longer be

disguised or confused with family

disintegration or delinquency. Parents'

contributions to their children's

board in the orphanages dropped

dramatically.42 The city's private

child-care agencies quickly ran out of

funds as endowment incomes

failed and the community chest made

dramatic budget cuts. In re-

sponse a public agency, the Cuyahoga

County Child Welfare Board,

was set up, which assumed financial

responsibility for 800 state and

county wards from the Humane Society and

the Welfare Association

for Jewish Children. These constituted,

however, less than 20 percent

of Cleveland," 52.

40. U.S. Government Publishing Office, Children

Under Care, 14; Children's Ser-

vices, MS 4020, "Annual Bulletin of

the Cleveland Humane Society," May 1926, 6,

Container 3, Folder 36.

41. Children's Services, MS 4020, U.S.

Children's Bureau, "The Children's Bureau

of Cleveland," 53, 54-59.

42. Cleveland Protestant Orphan Asylum, Annual

Report, 1926-29 (Cleveland, 1929),

58.

|

Homes for Poverty's Children 21 |

|

|

|

of dependent children; the rest were cared for by private agencies in the county.43 These financial exigencies prompted a survey by the Welfare Fed- eration, which showed that the numbers of children admitted to the orphanages had gradually declined during the 1920s. However, by the end of the decade fewer children could be discharged because the depression made it impossible to return them to their own poverty- stricken families or to place them with foster families who might be equally hard up. The orphanages were too crowded to accommodate the children of all the needy parents who wished placement.44 In 1933 the Children's Bureau starkly revealed the poverty of the parents of Cleveland's "orphans." Of the 513 families which had 800 children in child-care facilities, only 131 had employed members; 10 of these worked part-time; 8 for board and room only, and 300 families

43. Lucia Johnson Bing, Social Work in Greater Cleveland (Cleveland, 1938), 56; Emma 0. Lundberg, Child Dependency in the United States (New York, n.d.), 137. 44. Federation for Community Planning, MS 788 "Cleveland's Dependent Children," June 1931, Container 32, Folder 185. |

22 OHIO HISTORY

were "entirely out of work."

Yet only 97 were on relief. Few earned

as much as $20 a week; many more earned

less than $5. Almost none

could contribute to their children's

board in an institution.45

It is possible to argue that the poverty

of these children was only the

result of the Depression, that their

poverty was exceptional rather than

typical, but the evidence from earlier

years strongly suggests other-

wise. And in fact still another study

done in 1942, after the worst of the

Depression was over, showed that

"dependency" still described the

plight of 91 percent of the children in

orphanages; almost 60 percent of

parents made some payment for board but

33 percent were able to

make none; more than half were employed,

but seven percent were still

on public assistance, and almost 16

percent reported no source of

income whatsoever.46

Nevertheless, 1933 is a good place to

end this story of orphans and

orphanages, for it marks the beginnings

of the New Deal and the

assumption of major responsibilities for

social welfare by the federal

government. In 1935 the Social Security

Act established old age and

unemployment insurance programs and Aid

to Dependent Children.

Although these would not mean an end to

the poverty of children, these

programs would mean an end to orphanages

as their homes.

45. Ibid, "Analysis of

Financial Status," April 1933. Container 4, Folder 56.

46. Children's Services, MS 4020.

Children's Bureau, "Analysis of 602 Children in

Institutions . . . January 1,

1942," Container 4, Folder 60.