Ohio History Journal

BAUM PREHISTORIC

VILLAGE.

WILLIAM C. MILLS.

The Baum Prehistoric Village site is

situated in Twin Town-

ship, Ross County, Ohio, just across the

river from the small

borough of Bourneville, upon the first

gravel terrace of Paint

Creek.

The Paint Creek valley is drained by

Paint Creek, a stream

of irregular turbulence, flowing in a

northeasterly direction, and

emptying into the Scioto River, south of

Chillicothe. The Valley,

at the site of this village upwards of

two miles in width, is sur-

rounded on the east and west by high

hills which are the land-

marks of nature, but little changed

since the days of the pre-

historic inhabitants.

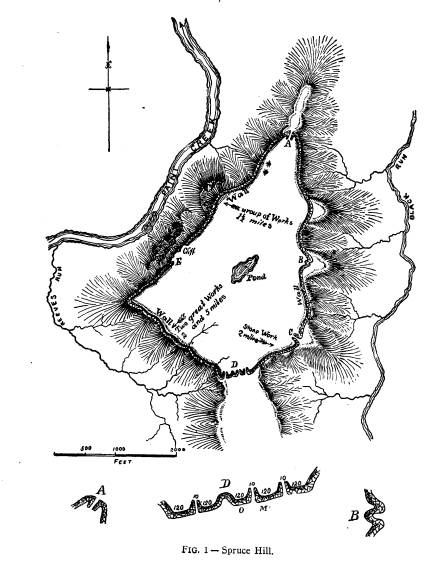

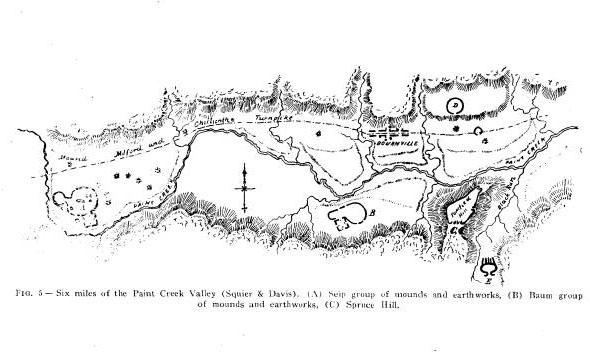

Spruce Hill, Fig. I, with steep slope

covered with a dense

forest, towers above the surrounding

hills on either side. The

top of this hill is made a veritable

fortress by an artificially con-

structed stone wall, enclosing more than

one hundred acres of

land. This fortress would no doubt

furnish a place of refuge to

those who might be driven from the

extensive fortifications in the

valley below, which are in close

proximity to the mounds and

village of those early people.

Looking to the south and east from the

village site, one can

see lofty hills rising in successive

terraces, no longer covered

with the deep tangled forest, but

transformed by the woodman's

axe, and now under cultivation,

producing the golden corn, which

is our inheritance from primitive man

who inhabited the Valley

of Paint Creek many centuries ago.

The village extends over ten acres or

more of ground, which

has been under cultivation for about

three-quarters of a century.

Almost in the center of this village,

near the edge of the terrace

to the west, is located a large square

mound. This mound and

the earthworks which are directly east

of it, have been known

since early times as the landmarks of

the early settlers in this

section of Ross county. The mound was

first described by Squier

45

|

46 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. |

|

|

|

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric Village Site. 47

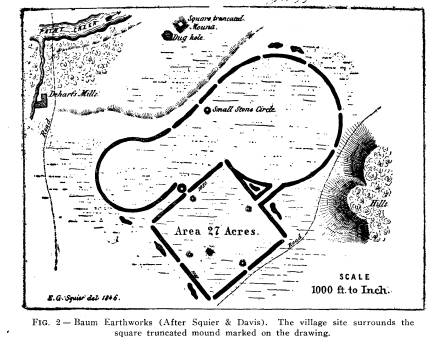

and Davis in 1846, in their Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, page 57, where they give a description and drawing of these works (Fig. 2). However, Squier and Davis do not men- tion the fact that a village was present, nor that they knew of the village, as is shown by their description. "This work is sit- uated on the right bank of Paint Creek, fourteen miles distant from Chillicothe. It is but another combination of the figures composing the works belonging to this series just described; |

|

|

|

from which, in structure, it differs in no material respect, except that the walls are higher and heavier. It is one of the best preserved works in the valley; the only portion which is much injured being at that part of the great circle next to the hill, where the flow of water has obliterated the wall for some distance. The gateways of the square are con- siderably wider than those of the other works--being nearly seventy feet across. A large, square, truncated mound occurs at |

48 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

some distance to the north of this work.

It is one hundred and

twenty feet broad at the base, has an

area fifty feet square on

the top, and is fifteen feet high.

Quantities of coarse, broken

pottery are found on and around it. A

deep pit, or dug hole, is

near, denoting the spot whence the earth

composing the mound

was taken." This description,

though meager, attracted the at-

tention of the Bureau of Ethnology, and

they sent a field party,

under the direction of Mr. Middleton, to

explore the mound, and

I herewith quote from the twelfth annual

report of the Bureau

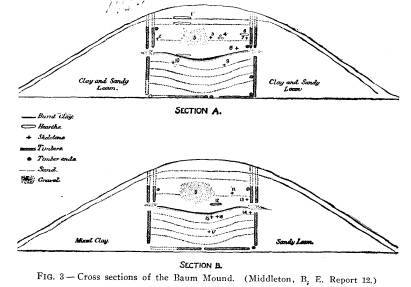

of Ethnology, 1890 and 1891. "The mound was composed for

the most part of clay, mottled

considerably with black loam and

slightly in some places with patches of

a grayish, plastic lime.

Cross trenches were run due north and

south and east and west,

respectively. The breadth of these at

the side was from five to

six feet, but as they penetrated inward

they widened gradually,

so that at the center the excavation

became thirteen feet in diam-

eter. Considerable lateral digging was

done from these trenches

to uncover skeletons and other

indications appearing in their sides.

"Two series of upright postmolds,

averaging five inches in

diameter equidistant ten inches, and

forming a perfect circle

twenty-six feet in diameter, constitute

a pre-eminent feature of

this mound. Within these circular

palings the mound was pene-

trated systematically by thin seams of

fine sand, sagging in the

center and averaging one foot apart.

Resting upon the natural

black loam at the bottom, timbers

averaging eight inches in di-

ameter radiated from the center, and in

the south and west

trenches were noticed to extend

continuously to the posts. These

timbers were detected, for the most

part, by their burnt remains

and also by the molds of dark earth in

the yellow clay, produced

by the decomposition of wood. Directly

over these timbers was

a horizontal line of decayed and burnt

wood, but mostly decayed,

averaging half an inch thick. The

upright postmolds of the lower

series were very distinct and measured

five feet in vertical height.

In one was found a small sliver of what

appeared to be black

walnut. Several of them contained the

burnt remains of wood,

and in many of these instances the black

bark was clinging to

the sides.

"Separating this from the

superstructure, as will be seen by

|

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric Village Site. 49 reference to Fig. 3, was a thin, sagging streak of burnt clay. Here and there upon its surface scant traces of black wood ashes were seen, while a small quantity of white bone ashes lay scattered upon its western border. This burnt streak overlaid a thin sand seam, below which it seems it could not penetrate. The post- molds of the superstructure consisted of a double row, the outer one being uniformly directly over the lower series in a vertical line, and separated from the latter entirely around the circle by a solid line of gravel. The two rows of the upper structure |

|

|

|

averaged eighteen inches apart. Both might have extended orig- inally above the surface of the mound, since they were discovered between one and a half and two feet beneath the surface, which had been considerably plowed. Horizontal timber molds a little smaller in diameter, filled, in places, with charcoal, could be distinctly seen lying against the side of each line of posts at the points shown in the figure. These appear to have been cross beams or stays used for bracing purposes. In the eastern trench a gap, three feet wide and two inches deep, was noticed by the absence of postmolds in both upper and lower series. Vol. XV -4. |

50 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

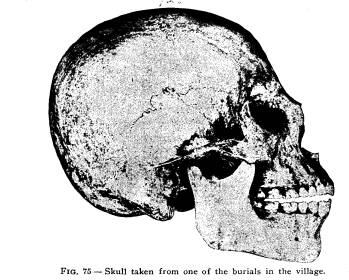

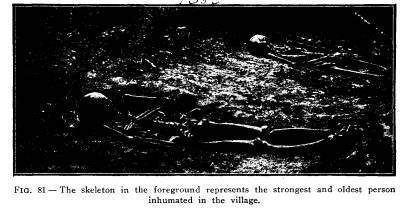

"All the skeletons discovered were

in the area inclosed by

these posts. The skeletons unearthed

were all in a remarkably

good state of preservation. None of them

could have been in-

trusively buried, for the stratification

above them was not dis-

turbed. All excepting Nos. 15, 16 and 17

lay upon one or another

of the thin seams of sand.

"With skeleton No. 1 a bone

implement was found at the

back of the cranium, and an incised

shell and fragments of a jar

at the right side of it. With No. 3,

which was that of a child about

ten years old, a small clay vessel was

found five inches behind

the cranium. At the left hand of

skeleton No. 8 was a shell

such as is found in the sands of Paint

Creek. A bone imple-

ment was at the back of the cranium of

No. 9. With skeleton

No. 11, were found a lot of small

semi-perforated shell beads,

and two bone implements directly back of

the cranium. By the

right side of the cranium were the

perfect skull and jaws of a

wolf, and beneath these were two

perforated ornaments of shell.

In the right hand was a shell, such as

is found in the creek

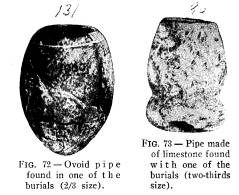

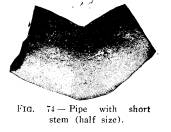

near by, while in the left was a pipe

fashioned from stone.

"At the right of the feet of this

skeleton was the extremity

of an oblong ashpit, about four feet

long and two feet broad and

one foot ten inches in depth. It was filled with white ashes

which were evidently those of human

bones, since none but

human bones could be identified. In

these ashes and compactly

filled with them, was an earth pot. It

lay at the right of the

feet of skeleton No. 11. It was lifted

out of the ashes with

great care, but the weight of its

contents and its rotten condi-

tion caused it to break in pieces before

it could be placed upon

the ground. Numerous other pieces of

pottery of a similar char-

acter were found in these ashes, and it

is not improbable, from

the indications, that all these ashes

were originally placed in pots

before interment. A perforated shell

disk, two inches in diam-

eter, and a lump of soggy sycamore wood

were gathered from

the ashes. Neither wood nor shell bore

any signs of having

been burnt.

"Skeleton No. 15 lay seven feet

deep and a half foot below

the general burnt streak. It was

originally covered with a wooden

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric

Village Site. 51

structure of some kind, for the cores of

two red cedar timbers

were resting lengthwise upon the body

and the burnt remains

of probably two others could be plainly

seen on each side, placed

parallel to those upon the body. This

red cedar was still sound,

but the white wood which envelopes the

red cores seemed to be

burnt entirely to charcoal. The

indications are that these tim-

bers were originally one foot above the

body, for the earth to

that extent over the whole length of the

body was very soft.

The timbers were noticed to extend

slightly beyond the head and

feet, while the head upon which they lay

was upon its right side.

The earth above them was a mixture of

clay and fine sand and

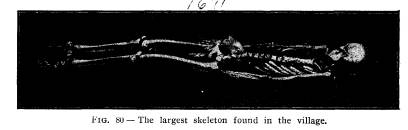

peculiarly moist. The length of this

skeleton to the ankle bones

was six feet and one inch. Two bone

implements were found

at its head, and at its right side near

the head were two frag-

ments of polished tubes and a

hollowpoint of bone, which ap-

pears to have been shaped with a steel

knife. Three bone im-

plements were found beneath the right

elbow of skeleton No. 13."

I have quoted at some length from the

Report of the Bureau

of Ethnology, because it is the only

account we have of the ma-

terial taken from the mound, which is

located almost in the

center of the village site.

However, the contents of the mound are

not available for

inspection, at the U. S. National

Museum, and we are compelled

to rely upon the description and drawing

given by the explorer,

Mr. Middleton, both in regard to mode of

burial and the arti-

facts placed in the grave. So far as I

am able to judge by hav-

ing before me the description of the

explorations of the mound

and the implements, ornaments and

pottery found in such pro-

fusion with the burials in the village,

I would say that the builders

of the mound were isochronological with

the dwellers in the

village. The bone arrowpoint mentioned

in the latter part of the

quotation as having the appearance of

having been shaped with

a steel knife, was duplicated many times

in every section of the

village, and was simply an unfinished

arrowpoint, having been

worked with a heavy piece of flint used

as a scraper, and not as

one would use a steel knife. An ordinary

pocket glass will reveal

the concave appearance of the cut, and

at the same time show

the scratches made by the uneven

fracture of flint. I have dis-

|

52 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

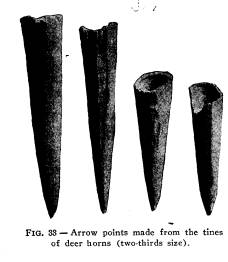

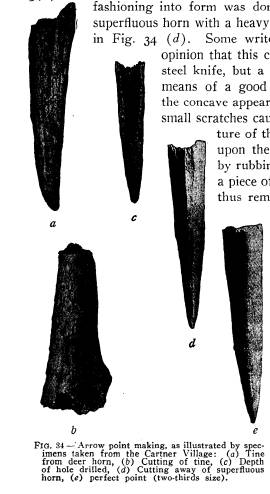

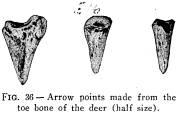

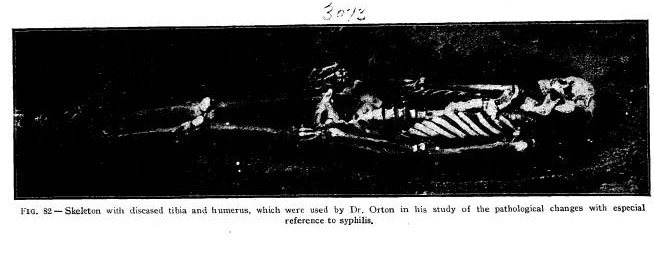

cussed at some length the making of arrowpoints, from the tips of the tines and the toe bones of the deer in the Explorations of the Gartner Mound and Village site, Ohio Arch. and Hist. Quarterly, Vol. XIII, No. 2. In 1897 Dr. Loveberry, under the direction of Prof. Moore- head, examined a small portion of this village, and I herewith quote from the conclusions of Prof. Moorehead, which are found in Vol. 7, page 151, of the publications of the Ohio State Archae- ological and Historical Society. |

|

|

|

"With other village sites of the Scioto this has much in common. While larger than the average, yet it can be said that it presents somewhat of a lower culture than others connected with great earthworks. It will be observed that there is not a great number of burial mounds within or without the enclosure. Those two to four miles west, along Paint Creek, may have been used by the occupants of the enclosure for their interments, but one cannot say positively. The character of the relics and the lack of evidence of high aboriginal art at this place are taken as evidence of the primitive character of the villagers. I do not |

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric Village Site. 53

think that they were the same people who

erected the earth-

work, or of the same tribe. At

Hopewell's, Hopetown, Har-

ness's and the Mound City fragments of

elaborately carved shells,

rings, polished pipes, both effigy and

platform, etc., have been

found. None of these truly polished,

ceremonial, or artistic ob-

jects were found in the ash pits or on

the habitation sites of the

Baum village site. The place is

interesting in that it shows a

lower degree of culture than that

evinced on the sites above men-

tioned. This naturally brings forward

the question--Is this a

later occupation? Is it an earlier one?

I am convinced that it

antedates the construction of the works.

I do not think it is

of the historic period, and if Indian,

of some tribe which knew

little or naught of agriculture. No

pestles were found. The

bones of animals and the unios from the

creek, found in such

profusion, would indicate the presence

of a hunting tribe. No

foreign substances were present. Flint

Ridge material was ab-

sent. Neither the effigy of the fox, nor

the rude sculpture upon

the pipe can be classed with the

beautiful carvings of other Scioto

Valley culture-sites."

From the above quotations it will be seen

that the Baum

Mound and Village Site has had some

attention from the Archae-

ologist and was considered by them of

more than ordinary im-

portance.

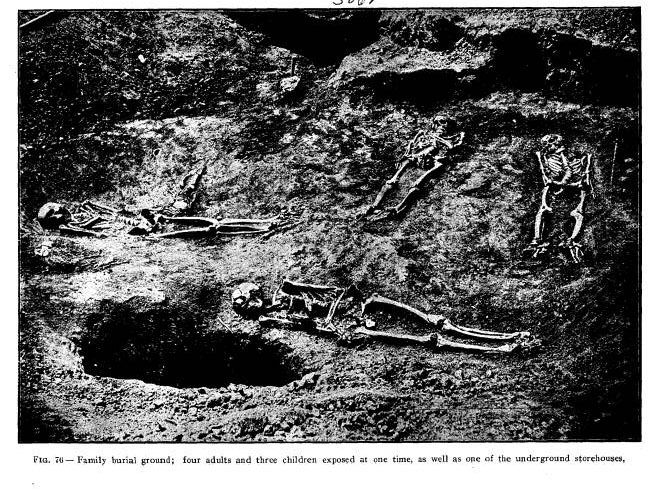

In the following pages I give a detailed

account of the work

of three seasons in the village,

bringing to light forty-nine tepee

sites which were more or less the

permanent abode of the dwellers,

one hundred and twenty-seven burials

which surrounded the

tepees and two hundred and thirty-four

subterranean storehouses,

in which were stored the winter supplies

and which were after-

wards used for refuse pits.

During the summer of 1899, I examined a

section of the vil-

lage which lays directly south of the

mound, extending the work

to the west, and finally ending the work

of the season directly

north of the mound. During the summer of

1903, I examined

a large portion of the village directly

east of the mound, and

during the summer of 1902, sections were examined northeast

of the mound, extending along the edge

of the gravel terrace,

directly southeast of the mound.

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric

Village Site. 55

The examination of these various

sections were made to

discover, if possible, the extent of the

village, as well as to

ascertain the mode of life in the

various sections, and whether

the same people inhabited the village in

all its parts.

The land upon which this village is

situated has been owned

by the Baums for more than three

quarters of a century. At

the present time the land upon which the

village proper is situ-

ated is owned by Mr. J. E. Baum and Mr.

Pollard Hill, and

through the kindness of these gentlemen,

I was not in any way

restricted in my examination of the

village; in fact, they as-

sisted me in many ways to make the work

pleasant and profit-

able. About three quarters of a century

ago, Mr. Baum's grand-

father cleared this land, which was then

covered with a growth

of large trees of various kinds, such as

the black walnut, oak

sycamore, and ash, and it has

practically been under cultivation

ever since. The top surface consists of

from twelve to thirty-six

inches of leaf mould, and alluvial

deposit, which overlies a thin

stratum of compact clay. Directly

beneath this clay or hardpan,

is found gravel.

During the entire examination of this

village, something less

than two acres of ground was dug over,

and examined inch by

inch by the aid of the pick, spade and

small hand trowel, bringing

to light the habitations and burial

places of these early people.

No one living in this section, not even

those cultivating the

soil for the three quarters of a century

mentioned, knew that the

remains of a buried city of a

prehistoric people lay only a few

inches beneath the surface. As the

examination progressed it

was evident that a few pages, at least,

of the history of remote

time, were being revealed in the deep

pits, which served as sub-

terranean storehouses for the early

agriculturists. A few more

pages were brought to light when deep

down in the clay, the

burial grounds for each family were

discovered, and still a few

more pages when the tepee, with its

fireplace, stone mortars, im-

plements and ornaments, lying in

profusion upon the floor of the

little home, partially told in silent

language of the great drama

of life, enacted by those early people.

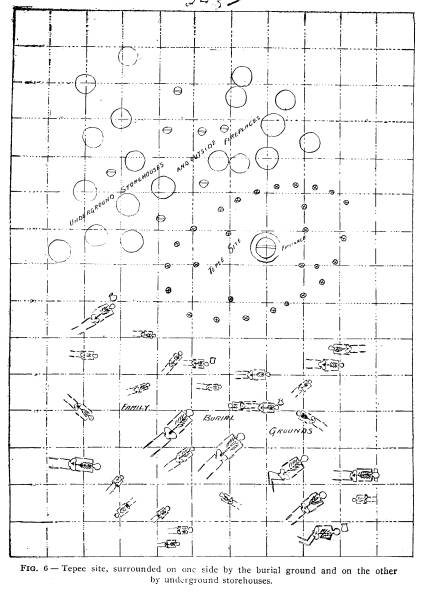

I herewith present a drawing, Fig. 6, of

a portion of the

|

56 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. |

|

|

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric

Village Site. 57

village farthest to the northeast of the

mound, which shows the

site of a large tepee, the largest found

during the explorations

and, perhaps, the most interesting in

this, that this tepee was

never changed and always occupied the

exact ground upon which

it was originally built, while in many

other instances the tepee

was shifted from place to place, even

occupying the ground used

for burial purposes, and the deserted

tepee site afterwards be-

ing used for the burial of the dead, or

for subterranean store-

houses. As I have stated, this tepee was

the largest found in

the village; of oblong construction and

measuring upwards of

twenty-one feet in length by twelve feet

in width inside of the

posts. The posts were large, as shown by

the postmolds, and

consisted of twenty-one set upright in

the ground, the smallest

being five inches in diameter and the

largest nine and one-fourth

inches. On the inside seven other posts

similar in size to the outer

ones were promiscuously placed,

presumably for the support of

the roof. The posts for the most part

consisted of the trunks of

small trees, with the bark attached,

placed in the ground. The

imprint of the bark was quite visible,

but the trees all being

young it would be impossible to identify

from the bark the kind

of trees used in the construction of the

tepee. The posts were

made the proper length by the use of

fire, and no doubt the

trees were felled by fire, for at the

bottom of the postmolds

charcoal was invariably found. The

covering of the tepee evi-

dently consisted of bark, grass or

skins, as no indications were

found pointing to the use of earth as a

mud plaster in the con-

struction of the sides or top. The

fireplace was placed in the

center of the tepee and was about four

feet in diameter, six inches

deep at the center and three inches deep

at the edge, and had

very much the appearance of having been

plastered from time to

time with successive layers of clay. The

earth beneath the fire-

place was burned a brick-red to the

depth of eight inches. The

original floor of the tepee had been

made fairly smooth, but almost

six inches of earth had little by little

and from time to time been

placed upon the floor. This earth had

scattered through it im-

plements and ornaments, both finished

and unfinished, polishing

|

58 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

stones, broken pottery, hammer stones, a large stone mortar, and many animal bones, especially of the deer, raccoon, bear, and wild turkey. As the animals named were most likely killed during the winter season, one must infer that the tepee was the scene of domestic activities during the winter, and that during |

|

|

|

the spring, summer and autumn the preparation of food was mostly done outside of the tepee at the large fireplaces marked upon the drawing (Fig. 6). However, the tepee described above is not typical of the village as far as size and shape and sur- roundings are concerned. The average tepee is about one-half the size and invariably circular in form, and the posts used in |

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric

Village Site. 59

their construction much smaller. The

inside of the tepees are

practically all the same. The

surroundings of the tepee, such as

the subterranean storehouses and the

burial places, depend upon

the size of the tepee. Surrounding the

large tepee just described,

to the south was the burial ground where

thirty burials were

unearthed, the largest in the village.

Of these burials twenty

had not reached beyond the age of

adolescents, showing that

sixty-six and two-third per cent. of the

family group never

reached the adult age. Fourteen of the

twenty were under six

years of age, showing that the mortality

among small children

was very great, being fully seventy per

cent., not taking into ac-

count the four small babies found in the

refuse pits which sur-

rounded the tepee. The mortality of the

young under the adult

age in this family is greater than in

any other individual family

discovered in the village. Out of one

hundred and twenty-seven

burials unearthed in the village,

seventy-four were under the age

of sixteen, showing that fully

fifty-eight per cent. of the children

never reached the adult age. Of the

seventy-four children under

the age of sixteen, fifty-six were under

the age of six years,

showing that fully seventy-five per

cent. of the children born to

these early peoples died before they

attained the age of six years,

not taking into account the twenty-four

very small babies found

in the ashes and refuse in the abandoned

subterranean storehouses

in various parts of the village.

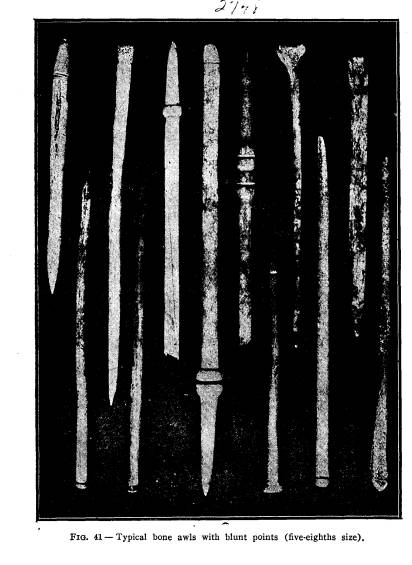

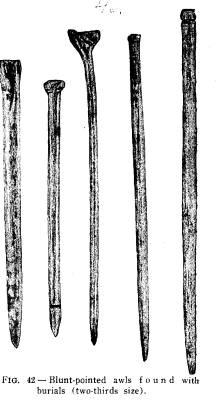

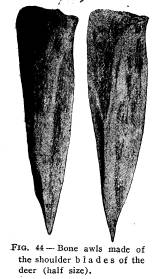

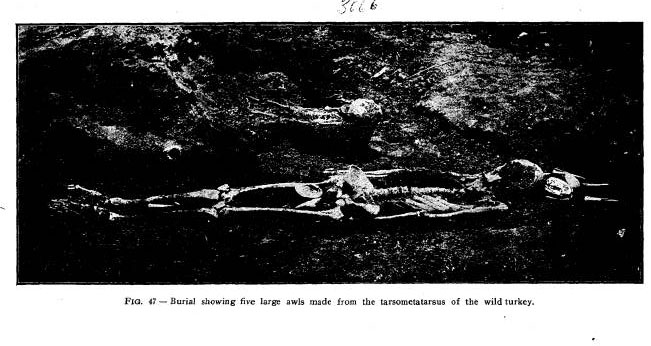

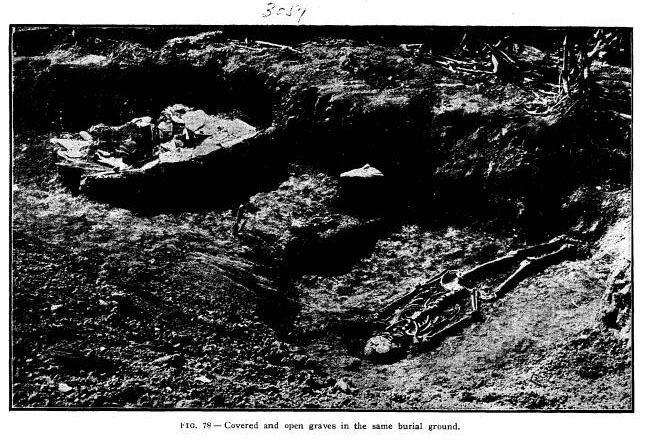

The burials of this wigwam group present

another interest-

ing feature, found in only one other

part of the village, that of

placing perfect pieces of pottery in the

grave. Four burials rep-

resenting five individuals, had each a

pottery vessel placed near

the head. All were carefully removed,

but were more or less

broken by freezing. The vessels have

been restored and will be

described elsewhere in this monograph.

Two of the vessels were

placed with adults and each contained a

single bone awl made

from the shoulder blade of the deer; a

few broken bones of the

deer and wild turkey were found in one,

and quite a number

of mussel shells with a few deer bones

were found in the other.

The other two vessels were placed in the

graves of children.

|

60 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

One with a double burial, as shown in Fig. 6, a few broken bones of the wild turkey were found in the vessel, together with two mussel shells worked into spoons. The vessel was placed near the head of the older child, whose age would not exceed four and one-half years. Two large bone awls made of the heavy leg bones of the elk were placed outside of the vessel and near the head, while in all the other burials where pottery was found, the awls were placed inside of the vessel. The other vessel contained |

|

|

|

bones of fish and a few small mussel shells, together with an awl made from the tibiotarsus of the wild turkey. Another interesting feature of one of the burials of this group and which was not found in any other section of the vil- lage, was the finding of a fine-grained sand-stone slab, nineteen and one-fourth inches long by five inches in width by one inch thick placed under the head of the skeleton. The slab had the appearance of having been water worn, but had received an ad- |

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric

Village Site. 61

ditional polish by rubbing, the effect

being noticeable over the

entire surface of the stone. One side is

perfectly plain; the other

side, finely polished, contains three

indentations about one-eighth

of an inch deep, and three-fourths of an

inch in diameter.

Another feature of this interesting

group is the finding of a

few copper beads associated with shell

beads in one of the burials.

This find is the only instance where

copper was found during the

entire exploration in the village.

However, it shows that the

denizens were familiar with and

possessed this very desirable

metal.

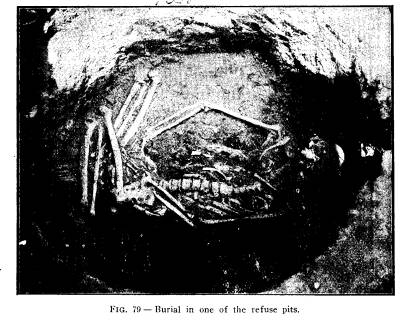

The refuse pits surrounding the tepee to

the north were per-

haps the most interesting in the

village, for here abundant evi-

dence was found showing that the refuse

pits were originally in-

tended and used for a storehouse for

corn, beans and nuts, and

perhaps, for the temporary storage of

animal food, etc., and

afterwards used as a receptacle for

refuse from the camp. For

some time I was of the opinion that the

large cistern-like holes

were dug for the express purpose of

getting rid of the refuse, but

as the explorations progressed I soon

discovered their real pur-

pose by finding the charred remains of

the ears of corn placed

in regular order on the bottom of the

pit; and I was further

rewarded by finding pits in various

sections of the village con-

taining charred corn, beans, hickory

nuts, walnuts, etc., which

had been stored in the pit and no doubt

accidentally destroyed.

Since completing my examination of the

Baum Village I ex-

amined the Gartner Mound as well as the

village site which sur-

rounded the mound, and find that the two

villages had very much

in common. The family grouping and the

subterranean store-

house were identical in every respect

with those at the Baum

Village, therefore, I quote from my

report upon this village site,

Vol. 13, page 128, publications of

the Ohio Archaeological and

Historical Society, including a

photograph of explorations at

Gartner's showing the close proximity of

the pits and the large

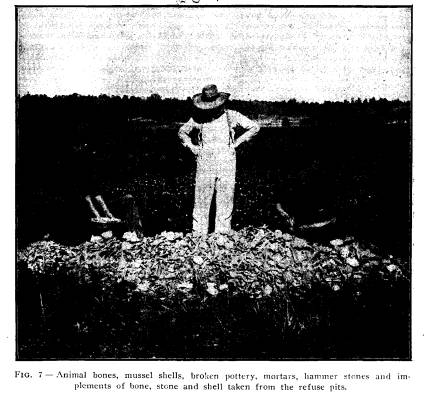

number exposed at one time: "The

refuse pits, which are so

abundant in the villages of the Paint

Creek valley, were present

in great numbers and distributed over

the village site surround-

62 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

ing the habitats of the various

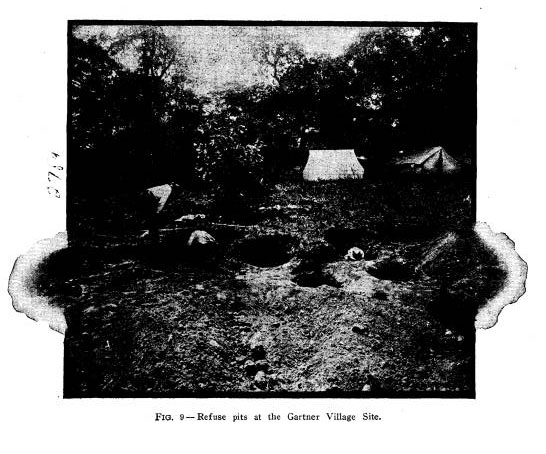

families. Fig. No. 9 shows ten of

these pits open at one time. During the

examination in the vil-

lage, more than one hundred pits were

found and thoroughly ex-

amined. The evidence produced by this

examination shows that

twenty per cent. of the pits examined

were originally used for

storehouses for grain, beans and nuts,

and perhaps for animal

food. These pits were lined with straw

or bark and in some in-

stances the ears of corn laid in regular

order upon the bottom;

in other instances the corn was shelled

and placed in woven bags;

in others shelled corn and beans were

found together; in others

hickory nuts, walnuts, chestnuts and

seeds of the pawpaw were

present in goodly numbers. All this was

in the charred state, acci-

dentally caused, no doubt by fire being

blown into these pits and the

supplies practically destroyed before

the flames were subdued.

The burning of these supplies must have

been a great loss to

these primitive people and may have

caused them great suffer-

ing during the severe winters, but it

has left a record of their

industry which never could have been

ascertained in any other

way. The great number of pits found,

which show conclusively

by their charred remains their early

uses, would lead one to be-

lieve that all the pits found were used

originally for underground

storehouses and by spring time, when the

supplies were likely

consumed, a general forced cleaning up

of their domiciles and

surroundings would occur and the empty

storehouse would serve

as a receptacle for this refuse, which

was henceforth used for

that purpose until completely filled.

During the autumn, when

the harvest time came, a new storehouse

would be dug and the

grain and nuts gathered and stored for

winter use. The exam-

ination of the pits has brought out the

above conclusions, as

evidenced by the refuse therein. Near

the bottom of the pits will

invariably be found the heads of various

animals such as the

deer, with antlers attached, black bear,

raccoon, gray fox, rabbit

and the wild turkey, as well as the

large, heavy, broken bones of

these animals such as would likely be

found around a winter

camp. Further, some of the large bones

showed that they had

been gnawed in such a manner as to

indicate the presence of a

64 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

domesticated dog, whose presence was

further corroborated by

finding his remains in every part of the

village. Therefore, tak-

ing all these facts into consideration,

one must necessarily infer

that the spring cleaning took place and

animal bones, broken

pottery and the general refuse was

thrown into the pits. Further,

the remains of fish are seldom ever

found near the bottom of the

pits, but usually occur from the top to

about the middle. Mussel

shells are never found at the bottom of

the pits, but are usually

found near the middle or half way

between the middle and top

of the pit. We know that fish and

mussels must be taken during

the spring, summer and autumn and are

certainly very hard to

procure during the winter." The

same conditions as described

above were found at Baum Village.

Another notable feature in this village

was the finding of

the Indian dog, and I quote from my

preliminary report, page

81, Vol. X, Publication of the Ohio

Archaeological and Historical

Society: "The bones of the old Indian

dog were found in great

numbers, and there is no doubt but that

this dog was one of

their domestic animals, for it is known

that dogs were domesti-

cated long before the earliest records

of history, their remains

being found in connection with the rude

implements of the

ancient cave and lake dwellers all

through Europe. However,

the history and description of the

Indian dog, in the ancient times,

is yet a subject far from solution. The

remains of the dog found

in this village site were described by

Professor Lucas, of the

Smithsonian Institute at Washington, as

being a short-faced dog,

much of the size and proportions of a

bull terrier, though prob-

ably not short-haired. Professor Lucas

says he has obtained spec-

imens apparently of the same breed from

the village sites in

Texas and from old Pueblos. Professor

Putnam, of Harvard

University, for more than twenty years

has been collecting bones

of dogs in connection with pre-historic

burials in various parts

of America, and a study of the skulls of

these dogs found in the

mounds and burial places in Florida,

Georgia, South Carolina,

Ohio, Kentucky and New York, and from

the great shell heaps

of Maine, show that a distinct variety

or species of dog was dis-

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric

Village Site. 65

tributed over North America in

pre-Columbian times. Appar-

ently the same variety of dog is found

in the ancient site of the

Swiss Lake dwellers at Neufchatel, also

in the ancient tombs of

Thebes in Egypt. Professor Putnam

further says: "This variety

of dog is apparently identical with the

pure-bred Scotch Collie

of to-day. If this is the case, the

pre-historic dog in America,

Europe and Egypt and its persistence to

the present time as a

thoroughbred is suggestive of a distinct

species of the genus canis,

which was domesticated several thousand

years ago, and also that

the pre-historic dog in America was

brought to this continent by

very early emigrants from the old

world."

He further states: "That

comparisons have not been made

with dogs that have been found in the

tribes of the Southwest,

the ancient Mexicans, and with the

Eskimo."

In the latter part of the fifteenth

century Columbus found

two kinds of dogs in the West Indies and

later Fernandez de-

scribed three kinds of dogs in Mexico,

and as Professor Lucas

has been able to trace the Baum Village

dog into the far South-

west, it is very likely one of the kinds

described by Fernandez:

However, it must be admitted that

comparisons have not been

made with sufficient exactness to place

the Baum Village dog

with any of those described by the early

writers.

During the entire exploration fifty

bones of the dog were

removed, representing perhaps as many

individuals. Some of

the bones showed marks of the flint

knife upon them, others

were made into ornaments, while others

were broken in similar

manner to bones of the deer and raccoon.

Seven skulls were

found, but all had been broken in order

to remove the brain.

During the explorations at the Gartner

Village, which is lo-

cated six miles north of Chillicothe,

Ohio, along the Scioto River,

remains of the Indian dog were found in

the refuse pits similar

to those at the Baum Village, and their

osteological character ac-

cord in every respect with the dog found

at the Baum Village site.

FOOD RESOURCES.

From our examination of this village and

the evidence re-

vealed by the refuse pits and the sites

of their little homes shows

that these early inhabitants were not

savages depending entirely

Vol. XV- 5.

66 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

upon the wild food for their

subsistence, but were barbarians hav-

ing a settled place of abode, a

developed agriculture, the storage

of food supplies for future use, and the

domestication of at least

one animal, namely, the Indian dog,

which of all animals would

best show adaptation to his master's

wants and pleasures.

ANIMAL FOOD.

It is evident from the large quantity of

animal remains found

in the pits, that the inhabitants of Baum Village site depended

upon the chase for a very large part of

their subsistence. Every-

where about the village, especially in

the abandoned storehouses

and in the sites of wigwams, the broken

bones of various ani-

mals, that were used as food, were found

in abundance. The

abandoned storehouse was a veritable

mine for animal bones. A

memorandum of all the bones taken from

one pit was made.

The pit measured three feet and seven

inches in diameter by

five feet ten inches in depth and

contained 375 bones and shells,

some of which were mere fragments, while

others, such as the

leg bones of the beaver, groundhog and

raccoon were in a per-

fect state. A summary of all the bones

and shells is as fol-

lows: Virginia deer, thirty-five per

cent.; wild turkey, ten per

cent.; two species of fresh water unios,

ten per cent; gray

fox, ten per cent.; raccoon, five per

cent.; black bear, five per

cent.; box turtle, five per cent.; the

remainder of the bones be-

ing divided about equally between the

groundhog, wild cat, elk,

opossum, beaver, rabbit, wild goose, and

great horned owl. By

far the largest number of bones were

those of the Virginia deer

(Odocoileus virginianus). Out of twenty barrels of bones

brought to the museum, fully thirty-five

per cent. were of this

animal. It will therefore be safe to say

that thirty-five per

cent. of all the animals used for food

by these aboriginal inhab-

itants of Baum Village were the Virginia

deer. At the Gartner

Village, six miles north of Chillicothe,

this animal constituted

fully fifty per cent. of all the animals

used for food.

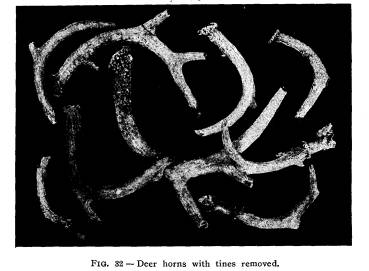

The general characteristic of the deer

at Baum Village was

similar to the modern species. The

antlers have a sub-basal snag

beyond which the beam is curved forward

and soon after forks

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric

Village Site. 67

dichotomously, the lower fork again

forking, presenting a beam

with three practical vertical tines

rising above it, thus demon-

strating that the Virginia deer has

remained practically unchanged

since the time of these aboriginal

inhabitants.

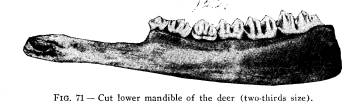

During the explorations three hundred

and fifty lower jaws

were removed from the refuse pits, which

would represent about

that number of individual animals. Of

this number only one jaw

has been removed in perfect condition,

the others being more or

less broken. Out of the three hundred

and fifty jaws examined,

fifty seven were from young deer under

the age of maturity, and

sixty-two were those of old animals

having their teeth very much

worn. In the remainder the teeth were in

a perfect condition,

and showed that the animal had reached

the age of maturity.

Fifty skulls of this animal were

procured from the refuse

pits, and only two, or four per cent. of

the fifty were females,

and the remaining forty-eight or

ninety-six per cent. were males.

Seventy-four per cent. of the males were

killed during the Fall

and Winter seasons, while only

twenty-two per cent. were killed

during the Spring and Summer. The small

per cent. of female

skulls shows that aboriginal man, in the

killing of animals, made

a selection with reference to the

perpetuation of the source of

supply. Moreover, the great quantity of

animals killed during

the Fall and Winter, shows that the

huntsman depended largely

upon animal food to tide him through the

Winter. In the other

seasons, corn, beans and nuts of various

kinds furnished him

his subsistence.

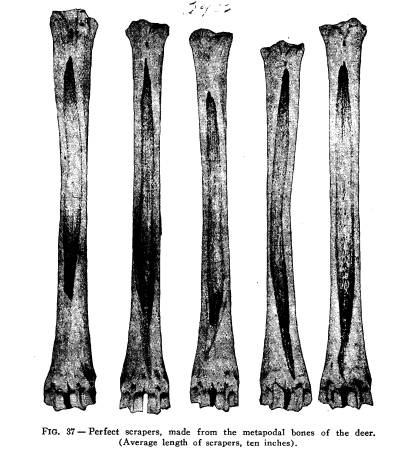

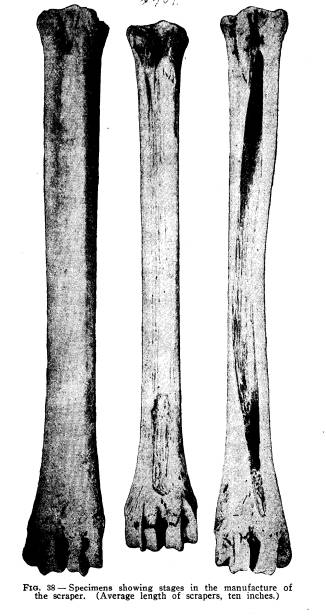

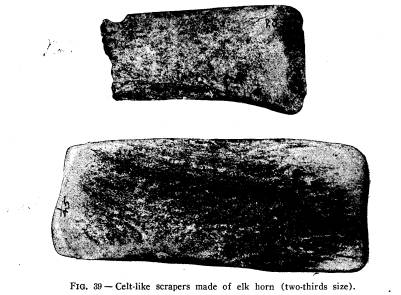

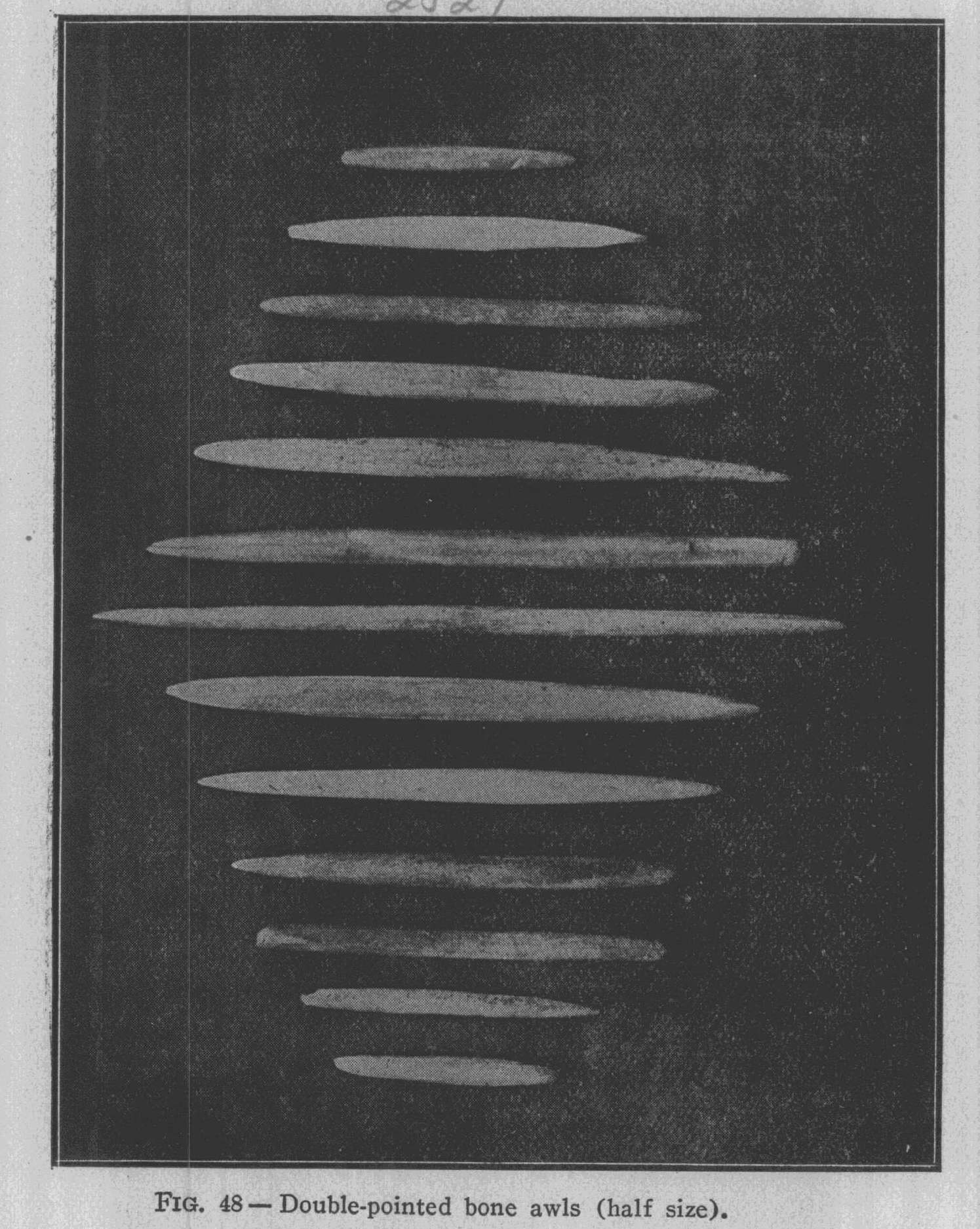

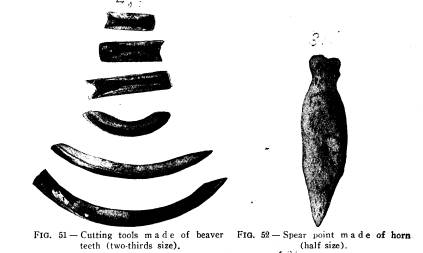

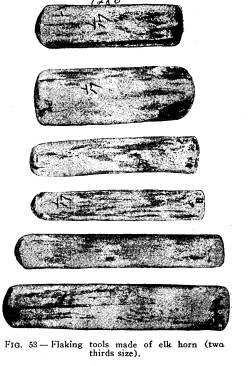

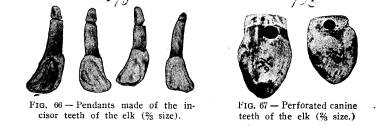

Elk (Cervus canadensis) -Is the largest mammal found in

the village. The bones of this animal

are not abundant in the refuse

pits, perhaps on account of the

difficulty in securing such a large

and fleet animal. Almost every pit would

reveal a few bones,

and these were broken into small pieces,

not a single perfect

large bone being found, as all had been

broken into small frag-

ments in order that every particle of

attached food might be

obtained. The large pieces of the heavy

leg bones were made

into awls and other implements, and the

metapodal bones into

scrapers; likewise every portion of the

large antlers were utilized

in the manufacture of celt-like

scrapers, flaking tools and spear

points.

68

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

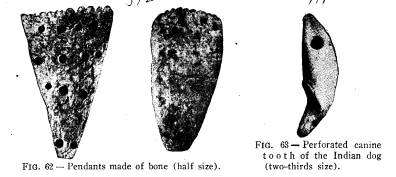

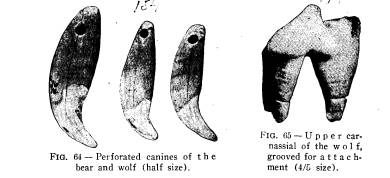

Black Bear (Ursus americanus) -Appear in goodly num-

bers in every section of the village.

Twenty-three broken skulls

were removed from the pits, all having

the posterior portions

broken away in order that the brain

might be removed. Seventy

lower jaws were found, but all were

imperfect, the defects be-

ing caused by the removal of the canine

teeth, which necessi-

tated destroying the jaw. The canines of

the bear are the only

teeth used for ornament, and are usually

perforated with a small

hole near the end of the root for

attachment.

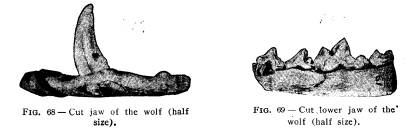

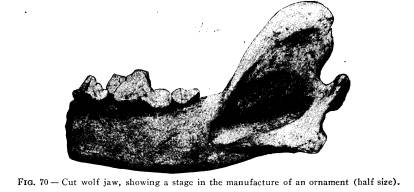

Wolf (Canis occidentalis)--Is another large animal found

very sparingly in the refuse pits, and

must have been very dif-

ficult to capture. During the entire

exploration only one head

was found with the teeth in place,

although quite a number of

upper and lower jaws cut into ornaments

were found. The large

leg bones were also broken into

fragments or made into imple-

ments. The canine teeth were perforated

near the end of the

root for attachment. The posterior

premolars were invariably re-

moved from the jaw and perforated for

attachment.

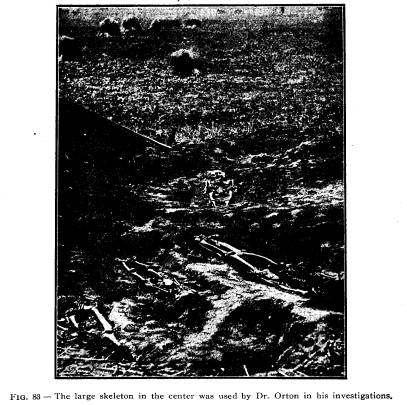

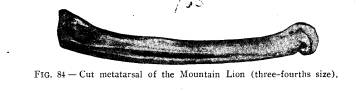

Mountain Lion (Felis concolor) -The bones of this animal

are not met with in abundance in this

village, although several

of the large leg bones have been found

as well as various por-

tions of seven skulls. The broken bones

are sparingly found in

every portion of the village, and the

teeth, such as the canines, the

upper posterior premolars and the lower

molars were perforated

and used as ornaments.

Wild Cat (Lynx rufa) - The bones of this animal are found

in great abundance in every section of

the village. Portions of

thirty skulls and parts of one hundred

and twenty-five lower

jaws were secured. Only a few perfect

leg bones were found

and these showed plainly the marks of

the flint knife in remov-

ing the flesh from the bones. The canine

teeth were much sought

after for ornament and not a single

lower jaw taken from this

village has the canine teeth in place.

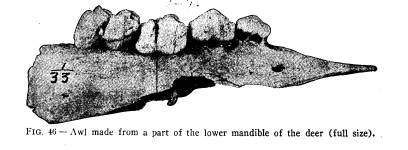

Raccoon (Procyon lotor)--The bones of the racoon are

more abundant in this village than any

other animal belonging

to the order Carnivora, although every

family of the order is

represented. The bones for the most part

were broken and not

more than ten perfect femurs were

secured. Thirty-five frag-

Explorations of

the Baum Prehistoric Village Site. 69

mentary skulls, one

perfect skull and two hundred and twenty-

seven parts of lower

jaws were taken from the pits. The perfect

skull was that of a

very old animal. The upper canine teeth

seem to be the only

teeth selected from the raccoon for orna-

ment. Many of the leg

bones were made into beads, and the

fibulas were

invariably made into awls or perforators.

Gray Fox (Urocyon virginianus) -This animal was

cer-

tainly plentiful in

this section of the Paint Creek Valley, as the

bones are found in

every part of the village. During the ex-

plorations over two

hundred lower jaws and over twenty frag-

mentary skulls were

secured.

Indian Dog (Canis) - This animal was found

in every sec-

tion of the village

and I have described this dog at some length

in the preceding

pages.

The dental formula is

as follows:

I. 3-3 C. 1-1 . P. 4-4 M. 2-2 =

42.

3-3 1-1

4-4 3-3

The canine teeth of

the lower jaw are quite large and strong,

the inner edge of

each being quite sharp. The first molar is large

with chisel-shaped

cones upon the surface of the anterior part

of the tooth, while

the posterior part is very large and flattened,

but has a number of

small cusps arising from the edge of the

tooth; this molar is

much larger than the second and third

combined. In the

upper jaw the first, second and third premolars

are very much alike,

although the first is single-rooted and not

so large. The fourth

premolar is very large, with cone-shaped

cusps arising from

the crown, the inner part chisel-shaped in

form. The two molars

are very different, although in general

character alike, as

the first is very much smaller than the second,

and both set at right

angles to the premolars. The outside of

the anterior molar is

made up of two large cone-shaped cusps,

while the inside of

the tooth is very large and flattened and the

crown low; likewise

the second molar has two cone-shaped cusps

upon the outside of

the tooth, but much smaller in size.

There is no doubt but

that this dog was a domesticated

animal and lived in

the village, as proof of his presence is man-

ifest in almost every

section of the village by finding many

large pieces of bones

that had been gnawed. This discovery led

70 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

me to believe, even before the remains

of the dog itself were

found, that his presence in the village

would be discovered. The

dog was also used for food, as his bones

were broken in a man-

ner similar to those of other animals

employed for food.

Skunk (Mephitis mephitica) was not found in abundance in

the village, though almost every tepee

site would reveal some

broken bones of this animal. During the

examination five im-

perfect skulls, two perfect skulls, and

twenty lower jaws were

found. The skulls were broken similar to

other animals, in order

to remove the brain, which was no doubt

used for food.

Mink (Putorius vison) -The bones of this

animal were

occasionally met with in every section of

the village. The bones

of such a small animal would readily be

destroyed by the Indian

dog. Three perfect skulls, ten

imperfect, and thirty-one lower

jaws were secured during the

explorations.

Otter (Lutra canadensis) - The remains of this

animal are

met with quite frequently. Twenty

fragmentary skulls and parts

of 23 lower jaws were secured. Not a

single perfect specimen

of the larger bones was found.

Fisher (Mustela pennanti) -

The remains of this animal are

sparingly met with and only two broken

parts of the upper jaw

with a portion of skull attached, and

five lower jaws, were found

among the entire explorations in the

village.

Opossum (Didelphs virginianus) - The remains of

this ani-

mal are found in more or less abundance

in the village, although

but few remains are found in the refuse

pits. Twenty imperfect

skulls and twenty-five parts of lower

jaws were found. The

upper canine teeth were much sought

after for ornament, per-

haps on account of their size and

general appearance, being long

and gracefully curved.

Ground Hog (Arctomys monax) - The remains of this ani-

mal were found in abundance in the

refuse pits. One perfect

skull, thirty imperfect skulls and one

hundred and five parts of

the lower jaw were secured.

Beaver (Castor canadensis) - The beaver is well represented

among the animal remains found in the

village. Fifty parts

of skulls and about the same number of

parts of lower jaws were

secured. The incisor teeth were highly

prized by aboriginal man

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric

Village Site. 71

when cut and made into ornaments and

cutting tools. The large

leg bones were also found unbroken and

might be considered

the best preserved in the village.

Musk Rat (Fiber zibethicus) -The bones of this animal are

not found as frequently as either the

Ground Hog or the Beaver.

One perfect skull and parts of three

imperfect skulls were taken

from the refuse pits.

Rabbit (Lepus sylvaticus) -The remains of the rabbit are

found in all parts of the village. Two

perfect, and parts of two

imperfect skulls were found, but the

large bones of the skele-

ton were everywhere abundant.

Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) -The remains of the

squirrel appear in great numbers,

although but parts of two

skulls were secured during the

explorations, and then only in

the last season's work in the village,

however, the various bones

of the squirrel were abundantly found in

almost every tepee site.

Weasel (Mustela vulgaris) -The bones of this small ani-

mal are occasionally met with in the

village, though it is rea-

sonable to believe that the bones of

this animal, as well as those

of other small animals, would be totally

destroyed by the Indian

dog. Portions of three skulls and five

lower jaws were found.

Rice Field Mouse (Oryzomys palustrus) -The rice field

mouse is found in great numbers in the

refuse pits, attracted

there evidently by the grain and nuts

stored for food.

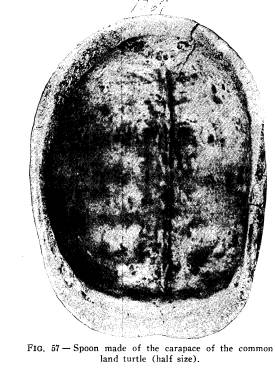

Box Turtle (Cestudo virginea) - The bones of the

common

box-turtle are very abundant in the

village. From one pit alone

fifty-nine carapaces were removed, which

no doubt represented

a turtle feast. The carapaces were

frequently cut and made into

drinking vessels and spoons.

Snapping-turtle (Chelydra serpentina)- This turtle is also

found in all parts of the village, but

not so plentiful as the box-

turtle.

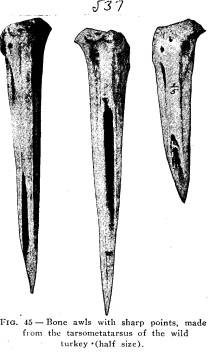

Wild Turkey (Meleogris gallaparo) - Fully eighty per cent.

of all the bones of birds found in the

village site belong to the

wild turkey. The flesh of this bird was

certainly highly prized

for food. The large leg and wing bones

were made into im-

plements and ornaments and the skulls

into rattles.

72 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

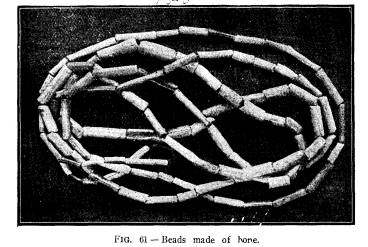

Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) - The bones of this

bird are sparingly met with, as

they were highly prized for

making ornaments, and the majority of

the large bones were cut

into beads.

Barred Owl (Syrnium varium) -The bones of the

barred

owl are occassionally met with. As with

the great horned owl,

the bones were made into ornaments.

Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) -

The humerus of this

bird was found quite frequently, but the

other large bones were

manufactured into implements and

ornaments.

Trumpeter Swan (Olor

buccinator)--Like the Canada

Goose, only humeri of this large bird

are found, and those spar-

ingly.

Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) -Only a few bones of

this bird were found.

Bald Eagle (Haliaetus leucocephalus) -Only a few bones

of the Eagle have been found - one

skull, several ends of large

wing and leg bones that were left from

the manufacture of some

ornament, and a few claws.

Mallard Duck (Anas boochas) Pintail (Dafila acuta) and

Canvas-back (Aythya vallisneria) are found frequently in the re-

fuse pits. Several skulls of each were

found.

The presence of great numbers of mussel

shells, both in the

pits and surrounding the tepee sites,

would indicate that this

shell fish was much used for food. At

the Gartner Village the

remains of large mussel bakes were

found,* but the large pits

used in the preparation of the mussels

for feasts were not found

at the Baum site. However, large holes,

from which earth had

been taken, perhaps for use in the

construction of the mound,

were filled with the shells, and

surrounding pits also contained

great numbers of the shells, indicating

that a great feast had

taken place, and that the mussels were

prepared in a way similar

to those at the Gartner mound.

* Accounts of the mussel bakes are given

in the Pub. of the Ohio

State Archaeological and Historical

Society, Vol. XIII.

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric

Village Site. 73

PLANT FOOD.

In order to secure data of certain

cultures in each coun-

try, historical records are quite

important and help to deter-

mine the origin of certain agricultural

products. These rec-

ords show that agriculture came

originally from three great re-

gions which had no communications with

each other, namely,

China, South West Asia and Egypt, and

inter-tropical America,

and from these three regions began great

civilizations based upon

agriculture. However, we find that

history is at fault in giv-

ing us much early data concerning the

third great center of civ-

ilization which does not even date from

the first centuries of

the Christian era, but we know from the

widespread cultiva-

tion of corn, beans, sweet potatoes and

tobacco, north and south

of the center of the American

civilization, that a very much

greater antiquity, perhaps several

thousand years, must be given

for the perfection of these plants up to

the time when history

begins.

The finding of charred corn, beans, nuts

and seeds of fruits,

and even the remains of dried fruit, in

the subterranean store-

houses in various parts of the Baum

Village, leads one to believe

that the early inhabitants were

agriculturists enjoying a certain

degree of civilization. The most

important product raised was

corn-Zea mays.* At the time of the discovery of America in

1492,

corn was one of the staples of its agriculture, and was

found distributed from the La Plata Valley to almost every

portion of Central and Southern United

States. The natives

living in this vast region had names for

corn in their respec-

tive languages. A number of eminent

botanists have made care-

ful explorations to find corn in the

conditions of a wild plant,

but without success.

The corn unearthed in the village was

always in the aban-

doned subterranean storehouses and

invariably at the bottom of

the pit. When any quantity was found the

charred lining of

the storehouse was present, which lining

frequently consisted

of long grass and sometimes bark. The

corn, when found in

* The identification of the corn, beans,

nuts and seeds from the

Baum Village was made by Professor J. H.

Schaffer of the Dept. of

Botany, Ohio State University.

74 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

the ear, was laid in regular order,

devoid of the husk, and con-

sisted of two varieties, an eight rowed

and a ten-rowed variety.

The eight-rowed variety had a cob about

half an inch in diam-

eter and short, while the cob of the

ten-rowed variety was larger

and longer. The grains and cobs having

been charred, were in

a good state of preservation.

In other pits the corn had been shelled

and placed in a

woven bag and the charred, massed grains

were removed in

large lumps with portions of the woven

bag attached. There-

fore it seems reasonable to believe from

the presence of so many

storehouses for the care and

preservation of their most nutritious

agricultural product, that corn was the

one staple upon which

prehistoric man depended to tide him

through the cold winters,

and until the harvest came again.

Kidney Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris)-According to J. S. New-

berry, who published the first flora of

the State (1859), the wild

bean occurs generally throughout the

State. This bean is found

in abundance in the pits, sometimes

mixed with shelled corn

and placed in a container, and sometimes

placed in the store-

house along with nuts and dried fruit of

the wild plum, and

was no doubt one of the agricultural

products of aboriginal man

of the Baum Village Site. According to

the latest discoveries,

in the Peruvian tombs of Ancon and other

South American tombs,

the origin of the bean was perhaps in

the intertropical Ameri-

can civilization, and no doubt spread

northward to the Missis-

sippi Valley similar to maize. Beans

were found also in the

storehouses at the Gartner Village,* and

in some of the burials

of the Harness Mound explored in 1905. Three species

of

hickory nuts were found in abundance in

the storehouse. Hicoria

ovata (shell bark) was taken from almost every pit where the

shells were found. Some of the perfect,

charred nuts were found

in the bottom of pits associated with

corn and beans, but the

ashes thrown into the pits from their

fire-places usually contained

many charred shells of this nut.

Hicoria minima (Bitter-nut) and Hicoria laciniosa were also

found in the ashes, but not so plentiful

as the shell-bark.

* Explorations

of the Gartner Mound and Village Site, Vol. XIII.

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric

Village Site. 75

Butternuts (Juglans cinera) and Walnuts (Juglans nigra)

were both found in the perfect charred

state in the storehouses

and the ashes from the fire-places

contained many shells.

Papaw seed (Asiminan triloba) and Hazelnut (Corylus amer-

icana) were also found in the bottom of

the storehouse.

Chestnut (Castanea dentata) found in small quantities in var-

ious parts of the village.

Wild Red Plum (Prunis

americanus) -The seeds were

found in the ashes and the charred

remains of the fruit with seed

were taken from one of the storehouses.

Wild Grape (Vitis (op) ) was found sparingly in a few of

the pits.

PREPARATION OF FOOD.

Food, for the most part, both animal and

vegetable,

was prepared by cooking, as evidenced by

the large fire-

places, the innumerable pieces of broken

pottery, and the mor-

tars and stone pestles used in crushing

the corn, dried meats,

fruits and berries. The fireplace was

always present within the

tepee, and several of them could always

be found outside of the

tepee and in close proximity to it. The

fireplaces often show re-

pair. When the hollow in the ground

became too deep by long

use it was filled up to the proper depth

by mud plaster. The

necessary precautions were not taken to

remove all the ashes

from the fireplace before the plaster

was applied, consequently

when the fire was again placed in the

fireplace it soon cracked

loose, and portions of burned clay were

removed with the ashes

from time to time as the fireplaces were

cleaned, and the ashes

with the broken lining were thrown into

the pits. The large

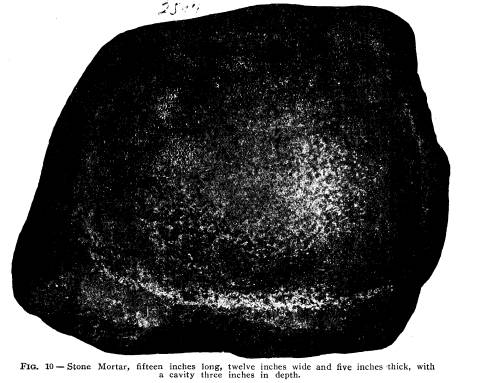

stone mortars, as shown in Fig. 10, were

found in every section

of the Village, and were made from slabs

of fine-grained sand-

stone, averaging in size from ten to

fifteen inches in length, from

seven to twelve inches wide, and from

four to seven inches in

thickness, with a depression on one

side, in many cases only

about one inch deep, while in others the

depression would be

several inches. The stone pestles used

in crushing corn and

preparing food to be cooked, were not

selected with any great

care nor was very much labor expended in

their manufacture, as

many of them were merely natural

pebbles, suitable as to size

|

76 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

and weight, slightly changed by a little pecking or rubbing, while others were natural flat and rounded pebbles, having a small de- pression cut on each side. None of the bell-shaped pestles found at the Gartner Village were found at the Baum Village, although the preparation of food products was the same. The use of pottery in the preparation of food was universal. |

|

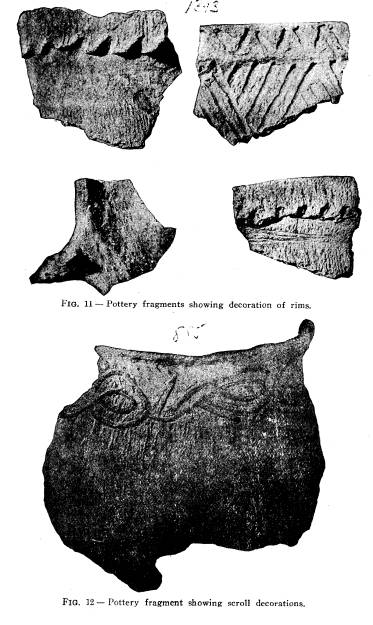

Everywhere in the village fragments of broken vessels, as shown in Figs. 11, 12 and 13, were found. Around the fireplaces both in and out of the tepee, pottery fragments were always present, showing that the pottery was broken while being used as a cook- ing utensil. The large pieces were gathered up and thrown into the open refuse pits near at hand, and here we find them quite often with particles of the charred food clinging to the sides of the broken vessels. The potter's art seems to have been |

|

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric Village Site. 77 |

|

|

|

78 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

known and practiced by each family group. They became ex- pert in successfully tempering clay to strengthen it, and in then carrying it through all the stages of modeling, ornamenting, |

|

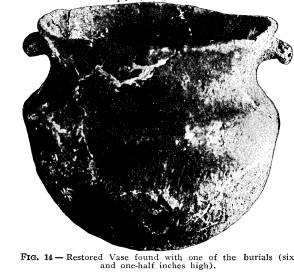

drying, and at last burning. Referring to Fig. 14, found with one of the burials, and which represents the highest type of fictile art found at the Baum Village, one can see the result of the pro- |

|

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric Village Site. 79 gressive operations of a very delicate and difficult nature which required skill, foresight, patience, and wide experience in the |

|

|

Ceramic art to produce such sym- metry and grace as is displayed in this vessel. The decorations were those made by textile markings, and occur over the entire surface of the vessel. The impressions were no doubt made with a paddle around which cords had been wrapped. The handles are dec- |

|

orated by indentations. Fig. 15 represents a vessel taken from another burial in the same family group. This vessel is also |

|

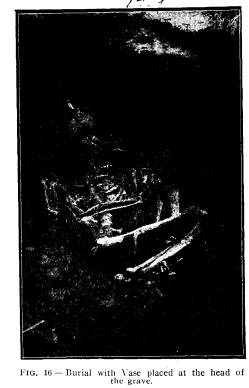

symmetrically made and the markings were made evi- dently with a pliable cloth, as they are uniform over the entire surface, including the handles. Fig. 16 shows a vessel placed near the head of the skeleton and which has been broken by freezing, as the burial was less than twenty-eight inches deep. Consequently all the pottery found in the burials of the Baum Village is more or less broken, but by carefully pre- serving the pieces, the ves- sel may usually be restored. |

|

|

80 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

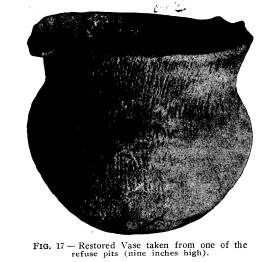

Fig. 17 is another restored vessel taken from the bottom of one of the storehouses in another section of the Village. The vessel had evidently been used as a container for grain and was accidentally broken in the pit and left there. Fortunately we secured all the pieces and were ably to fully restore the beau- tiful vessel. It is the largest one that we have been able to restore, although many others that were very much larger lacked only a few pieces to fully restore them. The restored vessel |

|

|

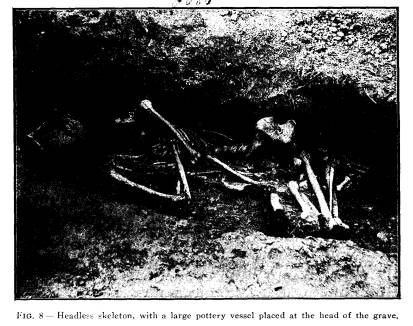

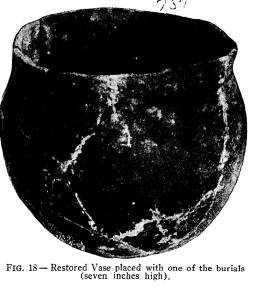

is nine inches high, with a diameter of nine and one-half inches at the largest part of the bowl. Fig. 18 is of a very plain vessel taken from a grave in another part of the village. This vessel has also been re- stored, and is s even inches high and eight inches in diameter at the widest part of the bowl. The vessel is perfectly plain, which is characteristic of about all the pottery fragments taken from this particular family group. Fig. 8 shows this same vessel before it was removed from the grave. The skeleton is |

|

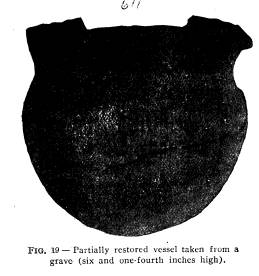

headless, and the vessel is placed where the head should have been when the body was placed in the grave. Fig. 19 is another vessel found with a burial. The vessel was fully restored with the exception of a piece of the rim, which had been broken out before being placed in the grave. The dec- |

|

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric Village Site. 81

orations are textile markings, and the impressions are very pro- nounced over the entire surface. |

|

|

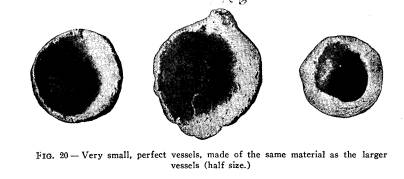

Fig. 20 shows very small vessels which were occasionally found in the perfect state; however, the broken pieces were found in every section of the village. The smallest of these vessels have the appearance of having been moulded over the end of the finger, while the largest is about the size of a small teacup. They were all rudely made and undecorated. Implements: The im- plements used in the |

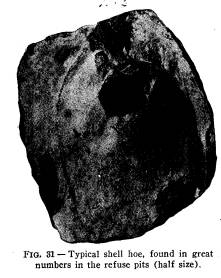

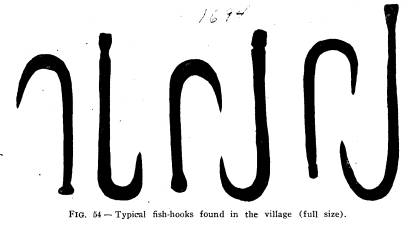

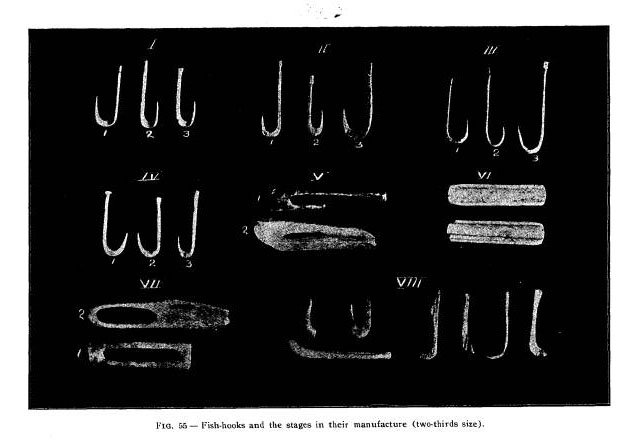

|

chase and for domestic and agricultural purposes were found in great numbers in the abandoned storehouses and the sites of the |

|

tepees. For the most part they were made from bone and horn, but implements made from flint and grani- tic bowlders were in evidence in all sec- tions of the village. The implements used for agricultural pur- poses and for exca- vating for the store- houses were made for the most part of large mussel shells. Im- plements made of wood Vol. XV - 6 |

|

|

82 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

largely used, as charred remains of digging sticks and pieces of wood that had been polished were frequently met with. |

|

|

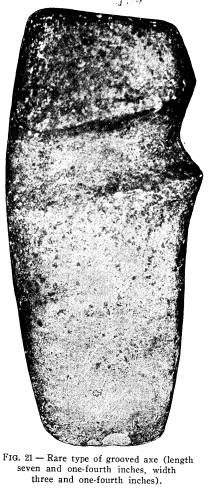

Stone Implements - The largest of the stone implements, with the exception of the stone mortars pre- viously described, were the grooved axes, which were sparingly found in the pits and tepee sites, two speci- mens having been found during the en- tire explorations, one in a tepee site and one in a refuse pit. The stone axe found in the tepee site is shown in Fig. 21. It |

|

is made of fine-grained blue granite rock, seven and one-fourth inches long, three and one-fourth inches wide. The surface shows the pecking, which had not been entirely obliterated by |

|

|

|

the grinding and polishing necessary for its completion. An interesting feature of this axe is the angle at which the groove |

|

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric Village Site. 83 |

|

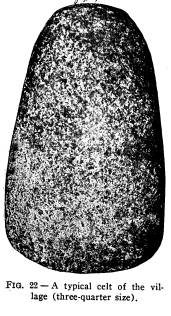

is cut to the blade. This type of axe is quite rare in Ohio, and not over four specimens are on exhibition in the mu- seum of the Society. The other axe found in one of the pits is an entirely dif- ferent type, the groove ex- tending entirely around the axe. It is made from the same compact stone as the axe described above, and is finished much in the same manner. Celts--This most useful implement was frequently met with in all sections of the village, and ranges in size from two to six inches in |

|

|

|

length. All are finely polished. Fig. 22 shows a typical celt found in the village. The celts were made for the most part from compact granite bowlders; others of banded slate and flint. Specimens illus- trating the various stages in the |

84

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

manufacture of the celt were secured

during the explorations.

Celts were frequently placed with the

burials. One was the

usual number placed in the grave, though

in several instances

two were found, and in the grave of a

large adult male, three

celts were placed in different parts of

the grave-one at the

feet, left hand and head, respectively.

The pits revealed many

broken celts, showing that the implement

was in general use.

Hammer Stones -The hammerstones, if abundance is to be

taken into account, were perhaps, the

most useful stone imple-

ments found at the Baum Village. In the

site of a single

tepee twenty-five to thirty would be

unearthed, and very often

as many would be taken from a single

pit. They were made

of small, water-worn bowlders, with a

diameter of two to four

inches, and the only evidence upon some

of the specimens show-

ing that they were used as hammerstones

was the battered ends

or sides; while others were artistically

smoothed and polished

on various sides, and perhaps covered

with a skin and used as

a club-head. However, it was not

necessary for aboriginal man

to expend unnecessary work upon an

implement when a natural

bowlder from the river near at hand

would answer the purpose.

Therefore it seems natural to believe

that all the bowlders of

proper size found in the village were

more or less utilized in

preparing meal, cracking nuts, breaking

bones of animals used

for food, etc.

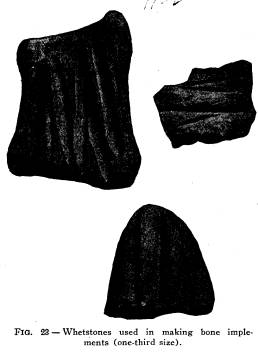

Grinding or Polishing Stones - Very good examples of this

most useful implement are shown in Fig.

23. They are usually

made of a fine-grained sandstone,* but

numerous pieces of coarse

grained sandstone taken from the top of

the hills, southwest of

the village were also found. The

grinding stones were indis-

pensible in the manufacture of the great

variety of bone im-

plements found in the village, and

varied in size from a slab of

sandstone one foot in length by a few

inches in thickness, to a

small piece of sandstone only a few

inches long and one inch in

thickness.

Chipped implements of flint were found

in every section of

the village, both the finished and

unfinished specimens, and were

*Waverly group.

|

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric Village Site. 85 |

|

|

made, for the most part, from flint pro- cured from the Flint Ridge section, and showing about all the grades secured at this famous prehistoric quarry. The colors also varied from the white or gray horn stone through the various shades of chalcedony to the variegated and banded jasper forms. The greater part of the flint was brought to the village in large pieces, and there worked into imple- ments, as several large pieces of flint |

|

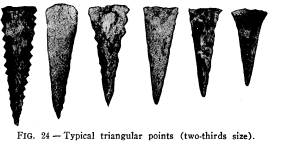

were found and the chips were everywhere present. The most abundant of all the objects made from flint were the small, tri- angular arrowheads, as shown in Fig. 24, which represents all the small triangular forms found in the village. Points with smooth edges were more abundant than those with serrated edges, and points having their edges both serrated and smooth are not uncommon. The |

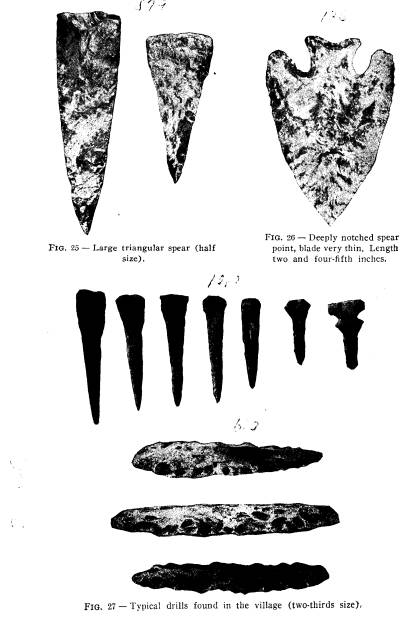

|

triangular form also predominates in the larger forms of spears, as shown in Fig. 25. The spear to the left is a type found in every section of the vil- |

|

|

86 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. |

|

|

|

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric Village Site. 87

lage. The beautiful spear point shown in Fig. 26 shows that the in- habitants of Baum Village were able to make points other than the triangular forms. This spear point is made of dark flint, having a |

|

|

|

very thin blade, deep notches, and an indented base, two and four- fifth inches long, and one and nine-tenth inches wide. Flint Drills, varying in length from two to four inches, were also abundant. Two kinds of drills were found: those having |

|

|

one point and usually small, and those having two points and much larger, but all have the same general appearance. Fig. 27 shows speci- mens which may be considered typ- ical drills found in the village. Flint Knives- |

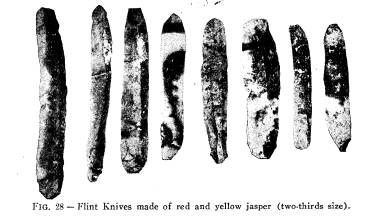

|

The flint knives flaked from the large jasper cores are also present. The knives are not large, and vary in length from one and one-half to three inches. Fig. 28 shows representative spec- |

|

88 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

imens made from banded and variegated jasper, showing sev- eral facets on the convex face, while the concave face is per- |

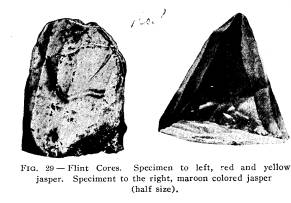

|

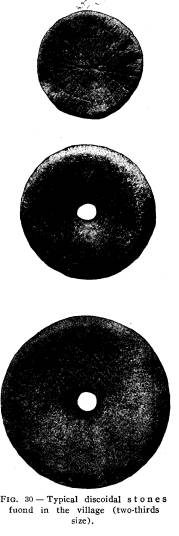

fectly plain and always regular and smooth -due to the fine grain of the chalcedony and jasper. Very few, if any, knives found in the village present any chipping, and all have the same general curve from end to end. The cores from which the knives are flaked are shown in Fig. 29, which represents the two types of cores found in the village, the conical core from which knives are flaked from all sides, and the flat core from which knives are flaked from one side only. The latter type prevails in the village. A large number of angular pieces of flint from one to one and a half inches in diameter were found in small caches near the site of the tepees, and quite frequently these angular pieces were found in the burials and were perhaps used to cut bone and horn, which were used in the manufacture of bone imple- ments. Discoidal Stones - Both per- fect and broken specimens were frequently met with in the refuse found in the abandoned storehouses. All of them were of small size, the largest not exceeding four inches in diameter, and the smallest less than one inch in diameter. Three types were found, the bi-concave, |

|

|

perforated at the center with a circular hole, the bi-concave un- perforated, and discs with perfectly flat sides. The bi-concave |

|

Explorations of the Baum Prehistoric Village Site. 89

with perforation, is the most abundant, and is made for the most part of diorite, and highly polished. The perforations are usually circular, but the finest specimen found in the village and made of quartzite had an oblong perforation. The specimen is shown in No. 2 of Fig. 30. Other specimens of this type were moulded out of tempered clay, the same as used in making pottery, but apparently were too fragile to be of great use, as all were broken. The second type, bi-concave unperforated, were larger than those that were perforated, but in every other respect similar. The third type or flat disc, which is also shown in Fig. 30, is of two kinds, plain and decorated. The plain are usually made of finegrained sandstone or pieces of pottery cut into form, |

|

|