Ohio History Journal

74 OHIO

HISTORY

and midwestern conditions.4 Moreover,

there survives an excellent

combination of materials describing the

topic in the state documents,

which outline the structure of public

finance and inspection, in the

BOSC reports (written by Byers), which

graphically portray condi-

tions in the institutions and conflicts

between local governments and

the state authorities, and in Albert

Byers's own diaries and a brief

but interesting file of letters sent to

him in his official capacity.5 When

these materials are used in conjunction

with the annual reports of the

National Conference of Charities and

Correction, it becomes possible

to reconstruct what we think is an

illustrative portrait of the formative

period of state welfare.

The bill creating the Ohio Board of

State Charities in 1867 was ad-

vocated by Republican Party reformers

who controlled state politics

for the better part of two decades,

beginning in 1855 with Salmon P.

Chase's election as governor.6 Three-time

governor, and later Presi-

dent, Rutherford B. Hayes was the other

major figure in this group.

The reform faith that the state should

encourage education, relieve

disease, reform the wayward and aid the

victims of war had pro-

duced a substantial number of

institutions by the end of the Civil

War. Three insane asylums, a

penitentiary, a blind asylum, a reform

school for boys, a deaf and dumb asylum,

and an institution for the

"idiotic" were in operation

while a fourth insane asylum, a soldiers'

home, and a soldiers and sailors'

orphans home were about to open.

There was active discussion on the need

for a girls' reform school

4. Few southern states created charity

inspection authorities before 1900, largely

because the number of institutions to

inspect was so small. By the late 1920s, however,

with southern urbanization and

industrialization well underway, Sophonisba P. Breck-

inridge reported "central

supervisory authority" in all but three states (Mississippi,

Nevada and Utah) and everywhere a trend

toward increasing the coercive power of this

authority. See Sophonisba P.

Breckenridge, "Frontiers of Control in Public Welfare Ad-

ministration," Social Service

Reviews, 1 (1927), 84-99. For further evidence of Ohio's typ-

icality see Robert H. Bremner, ed., Children

and Youth in America, I (Cambridge, 1970),

639-50; Ibid., II. 250-58:

Sophonisba P. Breckinridge, ed., Public Welfare Administration

in the United States: Selected

Documents, Second Edition (Chicago,

1938), 237-364.

5. A series of diaries belonging to

Byers are in box 5 of the Janney Family Papers,

Ohio Historical Society (OHS). He seems

to have used them as an aide-memoire and

they consist largely of brief factual

entries and a meticulous detailing of expenses. Subse-

quently, some of them were used for

other purposes, the 1864 volume, for example, for

press clippings from 1868. These in turn

have been annotated, probably much later to

judge from the hand. See also notes 21

and 37.

6. Ohio. Laws. LXIV (1867)

257-58: Ohio. House Journal (1867), 624. Ohio was the

third state to establish a charity

board, following Massachusetts (1863) and New York

(earlier in 1867). Seven other states

(North Carolina, Illinois, Rhode Island, Wisconsin,

Michigan, Connecticut and Kansas)

followed suit by 1873. For an excellent summary of

the various circumstances shaping the

development of these boards, see Gerald N.

Grob, Mental Institutions in America:

Social Policy to 1875 (New York, 1973), 270-92.

Origins of Welfare

75

and an "intermediate"

reformatory for male first offenders. In addi-

tion, the state paid annual subsidies to

the Longview Insane Asylum

(Cincinnati), Miami University and Ohio

University, while further ex-

penditures were likely as Civil War

veterans aged and as the state re-

sponded to the Morrill Act, which

granted to states the proceeds of

federal land sales for the establishment

of public colleges and univer-

sities. It must be added that although

these institutions were cre-

ated by one political faction, their

incorporation, like that of the

BOSC, received broad bipartisan

legislative support.7

But why was it necessary to create a state

authority to inspect pub-

lic institutions? Two reasons stand out.

First, legislators, pressured by

local philanthropic groups, had been

forced to take cognizance of

the generally dreadful conditions of

county and municipal jails and

infirmaries (almshouses). As the

incorporator of these governments,

the state had a legal obligation to

inspect their institutions and to pre-

vent cruel treatment and neglect.

Second, and of greater concern, leg-

islators felt increasingly unable to

control costs and monitor condi-

tions in the state institutions. A state

board of charity would, it was

hoped, bring local institutions up to

minimal standards, whittle

down the budgetary requests of the

various state institution trustee

boards and root out corruption wherever

found.8

A brief analysis of the financial and

governmental structure of late

nineteenth-century Ohio provides

pertinent background information

on these problems and thus the means for

explaining why the mis-

sion of BOSC was substantially

compromised from the outset. We be-

gin with two generalizations: First,

local government (that is, coun-

ties, townships, municipalities and

school districts) raised and spent

most of the public monies. Second,

though state expenditures were

therefore relatively small, a

significant and growing proportion of its

budget was devoted to education and

welfare expenses. Both of

these points require development.

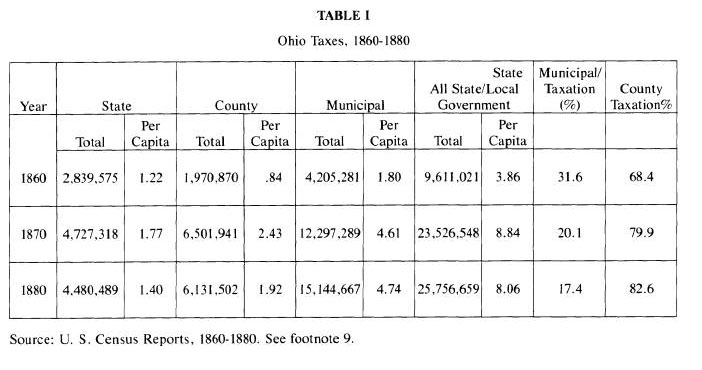

Table I, a summary of taxes collected by

local and state govern-

ment from 1860 to 1880, indicates the

local predominance.9 In 1860

7. For an example of legislative

approval of institutions, see Robert M. Mennel, "The

Family System of Common Farmers': The

Origins of Ohio's Reform Farm, 1840-58,"

Ohio History, LXXXIX (Spring, 1980), 131-34.

8. Ohio. House Journal (1867),

204-35, 624 and appendix, 235-37. An analysis of cor-

ruption at the state level is John P.

Resch, "The Ohio Adult Penal System, 1850-1900: A

Case Study in the Failure of

Institutional Reform," Ohio History, LXXXI (Autumn,

1972), 236-63.

9. Table I drawn from the following

sources: U.S. Census. Statistics of the United

|

76 OHIO HISTORY |

|

Origins of Welfare 77 |

78 OHIO HISTORY

county and municipal taxes were twice as

high as state taxes and the

difference increased during the decade.

County taxes increased at an

average annual rate of 23 percent, while

the municipal increase was

nearly 20 percent. County and municipal

taxation combined to ac-

count for over 80 percent of all public

levies by 1870, a proportion

which held steady in 1880 (and even into

the twentieth century).10

For state taxes the average annual

increase during the 1860s was less

than 7 percent, and the state percentage

of all taxation shrank from 32

to 20 percent, a share that declined

further by 1880. The municipal

burden remained the most substantial,

increasing during the 1870s

on both a total and a per capita basis,

while state and county taxes

decreased in both categories.

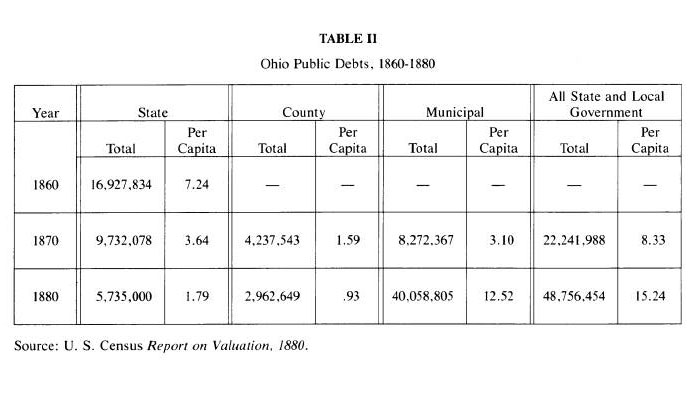

Table II, Ohio Public Debt from 1860 to

1880, emphasizes the

stress on municipalities. The figures

clearly show debt declining at

the state and county level while

climbing sharply in the towns and

cities.11 This was due, on the one hand,

to the retirement of state ca-

nal bonds and the completion of county

jails and infirmaries, and on

the other hand, to the capital

expenditures for the schools and pub-

lic works needed to meet the demands of

an urbanizing population.12

Although state taxation and debt were

declining in relation to local

burdens, welfare spending was creating

pressure upon available reve-

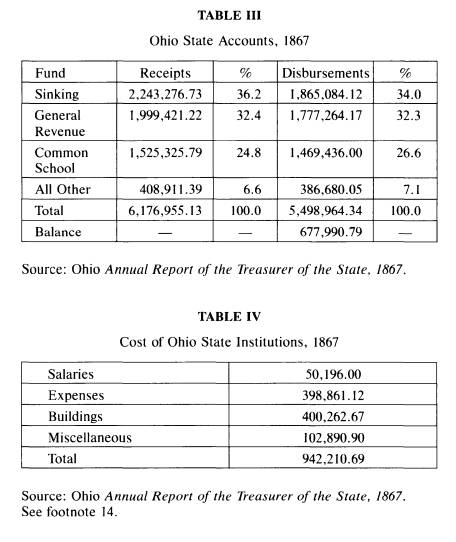

nue. The structure of state finance is

illustrated in Table III; 1867 is an

apt year since the BOSC was established

then. Of a series of separate

funds, whose income and expenditure were

kept independent from

each other, the three most important

were the Sinking Fund, the

General Revenue Fund, and the Common

School Fund. In 1867,

these funds accounted for more than 90

percent of both receipts and

disbursements.13

General revenue was the crucial account.

Representing about a

States in 1860. Mortality and

Miscellaneous Statistics (Washingtion,

D.C., 1866), 511;

U.S. Census, Eighth Census. The

Statistics of Wealth and Industry of the United States

(Washington, D.C., 1872), 11, 51; U.S.

Census. Ninth Census. Report on Valuation, Tax-

ation and Public Indebtedness in the

United States (Washington, D.C.,

1884), 25.

10. U.S. Census Bureau. Wealth, Debt

and Taxation (Washington, D.C., 1907), 767,

967-69. Ohio law allowed county

commissioners to hire "tax inquisitors" to pursue

evaders. The inquisitors were paid a

percentage of the amount they enabled the govern-

ment to recover.

11. U.S. Census. Ninth Census. Report

on Valuation .., 284-85, 612-13. County

and municipal figures are unavailable

for 1860.

12. These taxation and spending patterns

followed national trends. See U.S. Census

Bureau. Wealth, Debt and Taxation,

1913 (Washington, D.C., 1915). On the impact of ca-

nal building on Ohio finance see Harry

Scheiber, Ohio Canal Era; A Case Study of Gov-

ernment and the Economy, 1820-1861 (Athens, Ohio, 1969).

13. Ohio. Annual Report of the

Treasure of State (1867), 9.

|

Origins of Welfare 79 |

|

|

|

third of the total budget, it was supported by a general property tax and met the day to day running expenses of the state government. Its major commitments were salaries, legislative costs, and the expenses of the state institutions. Institutional costs, outlined in Table IV, made a decisive impact upon the state budget. In 1867, institutional build- ing and operating expenses accounted for 53 percent of disburse- ments from the General Revenue Fund-that is, more than than half the everyday operating costs of the state government-and 17 percent |

80 OHIO HISTORY

of disbursements from all funds.14 More

important, these costs

could not be controlled as easily as the

state's other major obliga-

tions, the Sinking Fund and the Common

School Fund. Although

these two funds accounted for 60 percent

of total disbursements in

1867, the Sinking Fund was declining in

importance as the canal

bonds were paid off while school

expenses were curtailed by the re-

quirement that localities bear the brunt

of costs. By contrast, legisla-

tors were annually beseiged for funds by

institutional trustees with

costs escalating to the point that

several delegates to the State Consti-

tutional Convention of 1873 feared state

insolvency.15

The situation was further complicated by

the fact that appointment

of institutional trusteeships

represented one of the few sources of pa-

tronage for the state's chief executive.

The state constitution denied

the governor a veto and allowed him only

a few appointments. Even

the trustee appointments had to be

confirmed by the state senate.

Thus, with each change of

administration, "reorganization" of trus-

tee boards was always a possibility.

Institutional trusteeships were

highly priced even though unpaid. Not

much could be made from

per diem expenses, but the offices conferred or recognized

status,

carried their own appointing power over

institution staff, and even

though trustees were barred from direct

commercial connection with

their institutions, they did determine

the placing of contracts. The

net effect was to create support for the

institutions and their programs

in both the legislative and executive

branches and thus dilute the

impact of cost cutting and efficiency campaigns.16

Given both the preponderance of local

government and the politi-

cal power of state institutions, it was

no surprise that in debate on the

bill to set up the Board of State

Charities, legislators weakened the

draft in order to protect their own

financial and political interests, to

cut costs and to leave patronage

undisturbed. The original bill pro-

vided the board with the services of a

modestly paid executive sec-

retary who was empowered to:

14. Figures recombined from the detailed

list of disbursements from the General

Revenue fund, Annual Report of the

Treasurer of State (1867), 12-15. This detailed listing

gives a total differing from that of the

summary recapitulation reproduced as Table III.

The recombination here has used the

detailed listing.

15. Ohio. Official Report of the

Proceedings and Debates of the Third Constitutional

Convention, I, part 3 (Cleveland, 1873-74), 200-38.

16. Most of the surviving Governors'

Correspondence for this period in the Ohio

State Archives is closely concerned with

patronage. Though fragmentary and damaged

by fire, these files are a mine of

tantalizing information.

Origins of Welfare 81

investigate and supervise the whole

system of the public charitable and cor-

rectional institutions of the state, and

counties, and shall recommend such

changes and additional provision as they

may deem necessary for their eco-

nomical and efficient administration.17

In the legislative give and take,

however, the words "supervise" and

"counties" were deleted,

leaving trustee boards unchallenged and

the localities subject to discretionary

rather than mandatory visits.

The power to inspect technically

remained because the state char-

tered local government and occasionally

subsidized local institutions,

but with the additional removal of the

provision for a paid secretary

the likelihood of regular inspections

appeared remote.

The law that emerged from debate, then,

confined the Board of

State Charities (whose members were to

draw only expenses) to visi-

tation and the gathering of information.

In this respect, the BOSC

was treated only slightly worse than

other state agencies. The Gas

Commissioner and the Inspector of Steam

Boilers had to use their

salaries and personal funds to purchase

testing equipment, while the

Inspector of Mines pleaded in vain for

one assistant to help him con-

duct inspections.18 In short,

these early boards and commissioners

were armed mainly with the weapon of

publicity. Personal conviction

and administrative skill would be the ingredients

of whatever suc-

cess they might achieve.

The first trustees of the Board of State

Charities suitably repre-

sented the reform wing of the Republican

party. Foremost among

Governor Jacob Cox's appointees in 1867

was Joseph Perkins, a

Cleveland banker, philanthropist and

railroad founder. Robert W.

Steele of Dayton helped organize the

first state agricultural fair and

tirelessly promoted public libraries and

higher education. Douglas

Putnam of Marietta had a distinguished

Civil War record and, like

the others, had formed his allegiance to

the Republican Party in the

anti-Nebraska agitation of the

mid-1850s. The other major figure of

the early board was John W. Andrews, a

Columbus lawyer who was

appointed by Governor Rutherford B.

Hayes in 1870. Representing

different parts of the state, these men

were united in belief-as Prot-

estants (Presbyterians or

Congregationalists) valuing good works as a

path to salvation and as Republicans who

saw their party as symbol-

izing God's blessing of the American

people.19

17. Ohio. Senate Journal (1867),

624.

18. Ohio. Docs. I (1867), 247-56;

Ibid., I (1870), 579, 583, Ibid., II(1876), 81-82.

19. Elroy M. Avery, A History of

Cleveland and its Environs, I (Chicago, 1918), 252,

337; The History of Montgomery

County, Ohio (Chicago, 1882), 244-45; History of

82 OHIO HISTORY

The trustees defined their primary task

as soliciting funds from

"private but influential

citizens" in order to pay the salary of an agent

or executive secretary. This position

had been deleted by the legisla-

ture but there could be little objection

since no state funds were in-

volved, at least initially. Practical

but also socioeconomic reasons ex-

plained their course of action. Because

the trustees had extensive

business interests, they could plausibly

claim that they would be

unable to fulfill the law's requirement

of substantive inspection of the

state's institutions. But they also knew

that the law's high moral in-

tent had been substantially compromised

by legislators who had

gutted the power of the board to enforce

its findings. Therefore, the

hiring of an agent would not only save

them time but also allow them

to express their displeasure at

institutional conditions without suffer-

ing directly the opprobrium of being

unable to effect change. What

they required was a person of some

repute who would view the posi-

tion as a promotion.20

Albert Gallatin Byers fulfilled their

needs. In 1867 he was serving

as minister of the Third Avenue

Methodist Church in Columbus and

also as chaplain at the Ohio

Penitentiary. In the latter capacity he

had made a reputation as a persistent

critic of the corruption and cru-

elty dominating the institution.

Penitentiary trustees may have been

glad to loan his services. Certainly,

the BOSC trustees hired him be-

cause of his zeal although their esteem

was measured because he

was poor. Years later, John Andrews

pityingly remarked upon Byers's

threadbare life when recommending him

for other jobs.21

Since Byers would more than repay the

trustees for their confi-

dence, it is worth knowing more about

him. He was born in Union-

town, Pennsylvania, in 1826 of

Scotch-Irish parents. He and his

brother and sister received a strict

Presbyterian upbringing, al-

though Albert became an accomplished

humorist and storyteller

who proudly emphasized his Irish

heritage. After his father's

death, the family moved to Portsmouth,

Ohio, where Byers began to

Washington County, Ohio (Marietta, 1881), 382, 483-85; History of Franklin

and Pickaway

Counties (1880), 68, 563, 566. These trustee positions were

renewable, and Perkins in fact

served for over twenty years.

20. Ohio. Docs., II (1868), 634.

In 1868 Rutherford Hayes gave the Board $500 from

the governor's contingency fund and the

following year the position of secretary was offi-

cially recognized and modestly funded by

the legislature. See Hayes to Joseph Perkins,

August 8, 1868, Governor's Papers, Box

8, The Papers of Rutherford B. Hayes, Hayes

Library; Ohio. Docs., II (1870),

371.

21. Andrews to Hayes, December 5, 1883,

and January 8, 1885, Hayes MS. See also

Albert G. Byers diary, March 15, 18;

April 1; May 1, 31; November 28, 1865, Byers Fami-

ly Papers, Ohio Historical Society

(OHS).