Ohio History Journal

"We feel you just haven't come to grips with the [manpower] problem or realized that there is a problem" declared Colonel George E. Strong, Industrial Relations Officer of the Army Air Forces.1 During World War II, Cleveland, Ohio, could not "come to grips" with its worker shortages in war production and essential service industries. In January 1943, the Cleveland War Manpower Commission created the first Womanpower Committee in the nation to recruit women for war work on a local level. This Committee's success made it a model for cities nationwide. Hesitant at first to use women in the war effort, because of a number of certain social and economic factors, the U.S. War Manpower Commission soon realized that the work force desperately needed women.2 However,

Julieanne Phillips is a Lecturer at the University of Dayton in the History Department. Her specialty is Women's and Cleveland History. She would like to dedicate this article to David Van Tassel, her Ph.D. advisor who passed away earlier this year. She would also like to thank Nikki Maxwell, Jimmy Meyer, Dorothy Salem, and the editors for their suggestions.

1. The

article title is taken from the War Manpower Commission's 1943 recruitment campaign

of women for essential civilian service jobs. The Federation of Women's Clubs

of Greater Cleveland (hereafter FWC), "Calendar for November, 1943," Bulletin

(Cleveland, Ohio, 1943).

2. For the leading studies on American women's roles during World War II, see

Karen Anderson, Wartime Women: Sex Roles, Family Relations, and the Status

of Women During World War II (Westport, Conn., 1981); D'Ann Campbell, Women

at War With America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era (Cambridge, Mass.,

1984); Rachel Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection

and Gender on the American Homefront, 1941-1947 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1997);

Alice Kessler Harris, Out to Work: A History of 'Wage-Earning Women in the

United States (New York, 1982); Susan M. Hartmann, The Home Front and

Beyond: American Women in the 1940s (Boston, 1982); Maureen Honey, Creating

Rosie the Riveter: Class, Gender, and Propaganda during World War II (Amherst,

Mass., 1984); Glen Jeansonne, Women of the Far Right: The Mothers Movement

and World War II (Chicago, Ill., 1996); Judy Litoff and David Smith, eds.,

American Women in a World at War: Contemporary Accounts from World War II

(Wilmington, Del., 1997); Leila J. Rupp, Mobilizing Women For War: German

and American Propaganda (Princeton, N.J., 1978); M. M. Thomas, Riveting

and Rationing in Dixie: Alabama Women and the Second World War (Tuscaloosa,

Ala., 1987); Winifred Wandersee, Women's Work and Family Values 1920-1940

(Cambridge, Mass., 1981); Doris Weatherford, American Women and World

War II (New

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee,

1943-1945

145

females did not come forward in the numbers needed. As a result, the Cleveland Womanpower Committee (CWC) implemented policies and programs to mobilize Cleveland women to meet worker shortages in defense and civilian service industries.

This article explores the CWC's efforts to recruit women for war work. It instituted campaigns, encountered problems, and achieved questionable results in recruitment. The CWC included eighteen European-American and two African-American women prominent in Cleveland. The CWC's successes and failures in organizing womanpower reserves in Cleveland particularize national attempts to recruit war workers. More importantly, the CWC is examined as a gendered middle-class response to World War II, and its experience provides evidence that goodwill and patriotism could not override the conventional priorities that defined American womanhood in the 1940s. This article discloses significant insights about race, class, and gender in the civilian war mobilization effort.3

Organization of the War Manpower Commission

To mobilize the work force for World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order No. 9139 on April 12, 1942, which created the War Manpower Commission (WMC). The WMC formulated programs and established "basic national policies" to "assure the most effective mobilization and maximum utilization of the nation's manpower in the prosecution of the war." The Commission consisted of Chairman Paul V. McNutt, former Indiana governor, representatives from the Departments of War, Navy, Agriculture, and Labor, and delegates from the War Production Board and its Labor Production Division, the Selective Service System and the U.S. Civil Service Commission. Subsequent executive orders added representatives from the National Housing Agency,

York, 1990);

Alan Winkler, Home Front, USA: America During World War II (Arlington

Heights, Ill., 1996). For a comprehensive essay on American women's roles during

World War II see, Judith N. McArthur, "From Rosie the Riveter to the Feminine

Mystique: An Historiographical Survey of American Women and World War It," Bulletin

of Bibliography, 44. See also Deborah Hirshfield, "Gender, Generation, and

Race in American Shipyards in the Second World War," The International History

Review, 21 (February, 1997); Karen Anderson, "Last Hired, First Fired: Black

Women Workers During World War II," Journal of American History, 69 (June,

1982), 82-97, Eleanor Straub, "United States Government Policy Toward Civilian

Women During World War It," Prologue (Winter, 1973), 247; Straub, "Women

in the Civilian Labor Force," Clio Was A Woman: Studies in the History of

American Women. Mabel E. Deutrich and Virginia C. Purdy, eds. (Washington,

D.C., 1980), 206-26.

3. Kathleen Neils

Conzen, "Community Studies, Urban History, and American Local History," in The

Past Before Us: Contemporary Historical Writing in the United States, Michael

Kammen, ed. (Ithaca, N.Y., 1982), 291.

The Cleveland Womanpower

Committee, 1943-1945

146

the War Shipping Administration, and the Office of Defense Transportation. The Commission aided Chairman McNutt in establishing requirements for manpower, and in directing both civilian and governmental agencies on the proper allocation of available labor.4

Three days after McNutt's appointment as Chairman of the WMC, he announced that MANpower would be an accurate description of the work force he intended to fill jobs. A few days later, he corrected himself and admitted that women might be useful in a "few local areas on a voluntary basis," and he appeared to be "satisfied with having women wrap bandages for the Red Cross."5 Initially, the WMC had no women officers, an omission brought to light by Mary Anderson of the Women's Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor. From the beginning of the war, the Women's Bureau sought to facilitate the employment of women. It recognized the contribution that women could make and hoped that the emergency would advance the position of women in the American economy.6 McNutt responded to the Women's Bureau criticism; on September 4, 1942, he established the Women's Advisory Committee as part of the WMC.

The Committee assisted the WMC in developing appropriate policies with respect to womanpower. Headed by Margaret A. Hickey, a lawyer and business executive from St. Louis, the Committee included eleven prominent women representing women's clubs, labor unions, business, and educational institutions from various sections of the United States. Each Committee member tackled a special problem that women encountered in the work force. For example, Sadie Orr Dunbar, former General Federation of Women's Clubs President, chaired the Committee's Community Facilities and Services, which investigated the inadequate local services available to working women, such as day-care centers. The WAC studied Dunbar's findings and recommended solutions to the WMC. Despite such studies and recommendations, the Committee had no real influence with the WMC, as the Commission repeatedly ignored the women's campaign strategies. Hickey held no WMC voting rights and had no means to implement decisions. In short, she became a mere figurehead.7

The WMC's ambivalence toward the Women's Advisory Committee

4. George

Q. Flynn, The Mess in Washington: Manpower Mobilization in World War II (Westport,

Conn., 1979), 6.

5. Ibid., 173-74.

6. National Manpower Council, Womanpower: A Statement by the National Manpower

Council With Chapters by the Council Staff (New York, 1957), 145.

7. "History of the War Manpower Commission: Women's Advisory Committee," November

1943, Series V, Reel 14, Folder 19 (hereafter "History of the WMC/WAC-) Consumers

League of Ohio Records 1900-1976, MSS 3546, Western Reserve Historical Society.

Cleveland, Ohio. (hereafter WRHS). Flynn, Mess in Washington, 176. Rupp,

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

147

The Cleveland Womanpower

Committee, 1943-1945

148

and women in the work force reflected the concern that the Roosevelt administration and American society had regarding women violating their traditional roles as wives and mothers. A government publication on women's participation in defense activities stressed that women's 11 primary instinct has been, and still is, to cherish their greater interest in the protection of the home [and] the family." Alice (Mrs. Leverett) Saltonstall, wife of the governor of Massachusetts, summarized the view that women, in spite of the war, were still mothers above all: "Men's work is fighting the battles; women's is the task of keeping homes warm and true."8

Little initial interest surfaced in recruiting, training, and utilizing large numbers of women in the war effort. When the United States entered World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, approximately four million men remained unemployed as a result of the Great Depression. Thus the WMC did not think the country would have to "dip very far into its reserves of womanpower." However, as the war escalated and the military draft increased, worker shortages appeared. Just one year after the war began, the WMC needed women to fill factory and service jobs.9

The WMC mobilized workers under McNutt's principles of voluntarism and localism, never conscription. Acting on strong beliefs in American individualism, it never compelled civilians to work. In order to meet the employment needs of each community, McNutt deferred to local directors to make manpower mobilization decisions. He decided he could solve the national manpower problem only through local programs; one solution would not work for all communities in the nation. 10 To that end, McNutt delegated authority to field operations under local control.

Regional, state, and area WMC offices and local United States Employment Services (USES) offices comprised the WMC field operations. In July 1942, WMC Chairman McNutt appointed twelve Regional Manpower Directors, each to oversee a regional office. These directors, assisted by regional labor and management policy-making committees, coordinated the activities of the Selective Service System. They also developed and conducted all WMC recruiting, manpower utilization, and job-training programs at the regional, state, and local

Mobilizing

Women For War, 88, Straub, "United States Government

Policy Toward Civilian Women During World War II," 247.

8. Rupp,

Mobilizing Women For War, 139, Alice Saltonstall, "They Say Women are Winning

on the Homefront," Ladies Home Journal, 60 (June, 1943), 3 1.

9. National Manpower

Council, Womanpower, 145.

10. Clarence D. Long,

The Labor Force in War and Transition: Four Countries (New York, 1952),

3; Flynn, Mess in Washington, 11, 12.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

149

levels and maintained liaisons with other government agencies concerned with manpower. 11 The former state employment service directors, now called WMC state directors, reported to the WMC regional directors. Accordingly, state directors established WMC area directors, assisted by area labor and management policy-making committees and the local USES offices in major war- manufacturing cities.

The regional, state, and area organizational structure paralleled that of the national WMC on a smaller scale. Hence, the WMC's decentralized arrangement made it possible for the local USES and area offices to be the basic operating units. Under McNutt's system, each major city had its own local committee of the WMC to oversee the mobilization of workers in its area. Each local committee recruited and placed workers in accordance with WMC employment stabilization and manpower priority programs and furnished basic labor market data for manpower planning at the state, regional, and national levels. Area committees had as their goal to recruit an abundant supply of workers to fill government contracts for war materials. By December 1942, from the 160 major industrial cities in the nation as identified by the WMC, labor shortages prevailed in 1] 6 areas. An inability to place enough war workers in such needed areas plagued the WMC throughout its existence. 12

In order to keep abreast of the ever-changing work force, the WMC reclassified manufacturing cities each month into four groups: Group 1: Areas of current critical labor shortages; Group 11: Areas of labor stringency and anticipated shortages within six months; Group III: Areas where a slight labor surplus would remain after six months; Group IV: Areas with substantial labor surplus. The U.S. Government did not place war contracts into Group I critical areas because understaffed manufacturers in those areas could not effectively handle the workload. Hence, a Group I classification led to a loss of revenue for the areas so designated.

A closer look at Region V of the WMC illustrates the relationships between the national, regional, state, and area WMC, and the local USES offices. It also demonstrates how the various levels of the WMC

11. The

12 WMC Regional Offices conformed geographically to the 12 regions of the Selective

Service Board. Region I- Boston: Conn., Me., Mass., NH, RI, VT.; Region II-

New York: NY.; Region III- Philadelphia: DE, NJ, PA.; Region IV- Washington,

D.C.: DC, MD, NC, VA, WV.; Region VCleveland: KY, MI, OH. ;Region Vl- Chicago:

IL, IN, WI.; Region VII- Atlanta: AL, FL, GA, MS, SC, TN.; Region VIII- Minneapolis:

IA, MN, NE, ND, SD.; Region IX- Kansas City, MO: AK, KS, MO, OK. Region X- Dallas:

LA, NM, TX.; Region Xl- Denver: CO, ID, MT, UT, WY; Region XII-San Francisco:

AZ, CA, NV, OR, WA.; "Inventory of the Records of the War Manpower Commission,"

RG 211, National Archives and Records Service. General Services Administration.

(Washington, D.C., 1973), 65.

12. Ibid., 30; Tex Wurzbach, Cleveland Press, December 17, 1942.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

150

interacted to mobilize war workers. Region V, which included Kentucky, Michigan, and Ohio, employed over 3,110 persons from its headquarters in Cleveland, Ohio. Robert C. Goodwin, age thirty-seven, former Regional Director for the Selective Service, worked with a staff of seventy to oversee the tri-state area. A director from each state reported to Goodwin on a weekly basis concerning labor needs and implementation of WMC programs. Goodwin informed the State WMC offices about the national directives to be followed and then reported back to the National WMC on the progress of the state programs. Ohio WMC Director E. L. Keenan supervised the departments of Employment Stabilization, Manpower Utilization, Minority Groups Services, Personnel and Training, Placement, and Veterans Employment. Eleven area directors, each representing a major manufacturing city in Ohio, reported to Keenan. 13

The Cleveland War Manpower Commission

Cleveland, Ohio, one of the most important industrial cities in Region V, produced such valuable war materials as steel and iron products, trucks and buses, fuel, and electrical goods. Some Clevelanders claimed that every American airplane and automobile included parts manufactured in their city. For the duration of the war, Cleveland factories worked around the clock to manufacture artillery and small arms, jeeps, aerial bombs, binoculars, telescopes, and bomber planes. 14 One local historian boasted that within a 500-mile radius of Cleveland "lived more than half the people of the United States and Canada," and they "produced 71% of the nation's manufactured products by 71% of its wage earners. Their earnings represented 75%" of the nation's payroll. Moreover, Cleveland, a major industrial lake port city at "the crossroads of industry," attracted new factories. By the 1940s Cleveland was a central hub for shipping and industry. The 1940 census population figure of 878,336 placed Cleveland sixth in demographic size in the country, behind New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, and Los Angeles. Cuyahoga County, which

13. Letter

to C.O. Skinner from R. Goodwin, September 20, 1943, Box 2453, Entry 269, War

Manpower Commission, Record Group 211, Reg. 5, Regional Central Files 1942-1945,

National Archives- Great Lakes Region, Chicago, IL. (hereafter WMC Records).

"War Manpower Commission in Ohio" Memorandum to WMC-USES Personnel, February

21, 1944, Index 11, Film 24, Ohio Bureau of Employment Services Records. Office

of the State Director. Columbus, Ohio (hereafter OBES Records). The I I major

war manufacturing cities in Ohio were Cleveland, Cincinnati, Akron, Columbus,

Toledo, Dayton, Youngstown, Canton, Bridgeport, Sidney, Lancaster.

14. William G. Rose, Cleveland: The Making of a City. Reprint ed. (Kent,

Ohio, 1990; Cleveland & New York, 1950), 970.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

151

encompassed the Greater Cleveland area, reported a 1940 population of 1,217,250, placing it ninth among the country's counties. 15 The city's labor force of 545,406 people included 150,000 female workers. However, while war work burgeoned at the city's defense plants, 3,000 to 4,000 greater Clevelanders were drafted each month into the armed services, and by December 1942, critical labor shortages threatened Cleveland's ability to manufacture valuable war goods. 16

To assist Cleveland in maintaining its war production, Ohio WMC Director Keenan created a Cleveland-area WMC. Keenan appointed Dr. William P. Edmunds, age fifty-seven, a former industrial relations manager for the Standard Oil Company of Ohio and a veteran of the U.S. Army Air Corps, as the Cleveland WMC Director. Under his guidance, the Cleveland WMC developed and directed "placement, training, and labor utilization operations within the area." Edmunds also consulted and coordinated with other government organizations such as Selective Service, local USES Offices, and the War Labor Board. 17 To assist in manpower decisions, in February 1942 Edmunds formed a WMC committee of seven men who represented Cleveland-area labor and management. Similar to the committees that assisted the WMC on the national and regional levels, the Cleveland committee included three presidents of area war factories, and two presidents and two secretaries of local labor unions. 18

Like the National WMC, the Cleveland committee faced the challenge of allocating sufficient workers to essential Cleveland war industries in order to keep the manufacturing of goods constant. The Cleveland WMC strived to supply "labor from the present population of Cleveland" while trying to keep the migration of workers from outside the city to an "absolute minimum."19 Already overwhelmed by large numbers of new residents-both immigrant and migrant-Clevelanders worried about further in-migration because of inadequate housing and city services.

15. Ibid., 965.

16. David D. Van Tassel and John J. Grabowski, eds. The Encyclopedia of Cleveland

History

(Bloomington, Ind., 1987), 1072; Wurzbach, Cleveland Press, December

17, 1942.

17. "Organization of the War Manpower Commission," December 26, 1942, Manual

of Operations: WMC, OBES Records.

18. The members of the Cleveland War Manpower Committee were: For

Industry: Albert S. Rodgers, President, White Sewing Machine Co.; H. P. Ladds,

President, National Screw and Manufacturing Co.; A. C. McDaniel,

President, Warner & Swasey Co. For Labor: W. F. Donovan, President,

Cleveland Independent Union Council; A. E. Stevenson, Secretary, Cleveland Independent

Union Council; W. Finegan, President, Cleveland Federation of Labor;

T. A. Lenehan, Secretary, Cleveland Federation of Labor.

19. Memorandum to F.J. McSherry from R. Goodwin. December 16, 1942. Regional

Directors Weekly and Monthly Progress Reports (hereafter Progress Reports) September

1942-December 1944, Box 3205, Entry 272. WMC Records.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

152

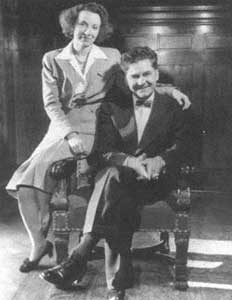

Cleveland Mayor Frank J. Lausche and his wife,

Jane, who was a member of

the Cleveland Womanpower Committee. (Photo

courtesy Cleveland State

University Library, The Cleveland Press Collection.)

Despite the desperate calls for more workers, many Clevelanders, like other Americans, attempted to "sit out the war."20 In December 1942, Cleveland Mayor Frank J. Lausche reported that the government had started turning away war contracts from the city because of a potential Group I critical classification. In light of this threat, Edmunds and the WMC Committee recommended that Cleveland use all of its available labor to the greatest possible advantage. To that end, Edmunds stressed that all women without small children or other urgent household

20. J. C. Furnas, "Are Women Doing Their Share in the War?" Saturday Evening Post, 216 (April 29, 1944), 12-13.

The Cleveland Womanpower

Committee, 1943-1945

153

responsibilities should prepare to enter employment. The same month as Lausche's warning, Edmunds "invited" 40,000 women not currently working to take a job either in a nonessential industry or to go directly into war work.21

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee

By January 1943, the WMC estimated that in Cleveland, 60,000 women were needed for war work. To recruit them, Edmunds created an experimental WMC subcommittee, the Cleveland Womanpower Committee. He appointed twenty notable local women to the CWC, including five women from personnel departments of war industries, four from organized labor, one representative of the Department of Labor's Woman's Bureau, two women representing African-American females, and the rest from local women's organizations such as the Federation of Women's Clubs, the YWCA, and the Consumer's League. The CWC, heralded as the "first of its kind in the nation," held its founding meeting on February 4, 1943.22 The Committee elected Dr. Mary Schauffler as CWC Chairperson. Schauffler, Assistant Professor of Sociology and Associate Dean of Women at Flora Stone Mather College in Cleveland (now Case Western Reserve University), held industrial personnel placement positions during World War 1.23

Designed to be a policy-determining group, the CWC governed the

21. Wurzbach,

Cleveland Press December 17, 1942; Cleveland Press, November 10, 1942;

Cleveland Press, December 8, 1942. National Manpower Council, Womanpower,

148.

22. The Cleveland Womanpower Committee members were: Mary Aikin, Eaton Manufacturing;

Lucy Bing, Chair, Joint Committee Consumers League-Women in War Industry; Doris

Birnbaum, C.I.O. Vocational Counselor; Margaret Cessna, A.P.L. Waitress Union;

Theresa Donahey, President-Traffic Council Ohio Federation of Telephone Workers;

Lena Ebeling, Sherwin-Williams Personnel Dept.; Helen Guthrie, Radmart Corp.

Personnel Dept.; Bernice Lander, Member, Federation of Women's Clubs of Greater

Cleveland; Jane Lausche, Wife, Mayor of Cleveland; Member Federation of Women's

Club; Bess B. LeBedoff, Johnston & Jennings Co. Women Employment Manager;

Elizabeth Magee, Executive Secretary, Ohio Consumers League; Mildred Melle,

Cleveland Graphite Bronze Co. and Mechanical Education Society of America; L.

Pearl Mitchell, Officer, Juvenile Court; Mrs. C. W. Rehor, Office of Civilian

Defense; Miriam Rogers, Secretary, Standard Oil of Ohio; Mary Schauffler, Dean

of Women, Flora Mather Stone College (Case Western Reserve University); Freda

Seigworth, Secretary, YWCA Industrial Dept.; Elizabeth Smith, Personnel Dept.,

Fisher Body Co.; Hazel Walker, Principal, R. B. Hayes School; Marie Wing, Regional

Attorney, Social Security Board; See Cleveland Press, February 4, 5,

1943; minutes "The Womanpower Committee of the War Manpower Commission, Cleveland

Area, February 4, 1943, Cont I Fol 15, Marie Remington Wing Family Papers 1849-1980,

MSS 4655, Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, Ohio (hereafter WRHS).

23. Memoranda to F.J. McSherry from R. Goodwin, January 12, 1943; February 10,

1943; February 15, 1943. Progress Reports. September, 1942-December, 1944, Box

3205, Entry

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

154

recruitment of women war workers and oversaw four functions: (1) To recommend policies affecting women and women's contribution to the war effort; (2) to review women's cases appealed from WMC decisions regarding their availability for war work; (3) to create and implement a Womanpower Center to register women for war work; and (4) to work through seven subcommittees, which included Planning, Publicity, Recruiting, Clubwomen Contact, Service (extension of store hours for war workers), and Scientific and Specialized Personnel (registration of women with education and training). The seventh subcommittee, Negro Women in Industry, planned ways and means by which more factories would employ black women on all jobs available to females.24

Similar to the relationship between the WAC and the National WMC, the CWC suggested policies and programs to the Cleveland WMC. Unlike the national WAC, however, the local CWC went beyond policy recommendations. The committee implemented its ideas for recruitment of women with the approval of the Cleveland WMC. The CWC opened the Cleveland Womanpower Center, registered and referred women to jobs, and instituted suburban door-to-door canvassing for women workers. CWC members personally publicized the need for women in the war effort with speeches on the radio and at women's club meetings, and in full-page newspaper advertisements.25

On March 5, 1943, the CWC opened the Womanpower Center in downtown Cleveland for a two-week trial with a staff of eight (later expanded to ten) as an "information, recruiting, and placement center for women workers." Easily accessible to shoppers and office and sales employees, the CWC's center was located in the middle of the busiest shopping district in the city. To coincide with the official opening of the center, a blitz of patriotic radio, press, and motion picture publicity saturated the area, emphasizing the need for women workers.26 The success of the center's two-week trial period-the first week of recruiting

272, WMC

Records, "Draft- Article on Womanpower Committee and Womanpower Center for Manpower

Review," April 5, 1943, Cont I Fol 15, Wing Family Papers, WRHS.

24. "Organization of Womanpower Committees" Memoranda to M.A. Clark from J.K.

Johnson, August 31, 1943, Regional Central Files 534.13, Women's Advisory Committee/

Women Power, Box 2466, Entry 269, WMC Records.

25. Letter to C. 0. Skinner from R. Goodwin, September 20, 1943, Progress Reports,

September 1942-December 1944, Box 2453, Entry 269, WMC Records; "Organization

of Womanpower Committees," Memoranda to M. A. Clark from J. K. Johnson, August

31, 1943, Box 2466, Entry 269, WMC Records. "What is this Manpower Problem?"

Pamphlet, WMC Region V, June, 1943, Minutes of the Womanpower Committee WMC,

October 4, 1944, Series V, Reel 14, Fol 97, Consumers League of Ohio Records,

WRHS.

26. The Cleveland Womanpower Center was located at 1020 Euclid Avenue. "Minutes

of Womanpower Committee," March 5, 1943, Series V, Reel 14, Folder 97, Consumers

League of Ohio Records, WRHS; Memoranda to L. A. Appley from R. Goodwin, March

8, 1943, Progress

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

155

alone attracted 2 15 female applicants-transformed it into a two-year project for the CWC. By September 1943, an average of 800 to 900 women per week utilized the Center's services of employment interviews and job referrals.27

During World War II, in Cleveland and the nation, economic mobility opportunities opened for European-American and African- American women. European-American females shifted to jobs previously held by men, and African-American women shifted to occupations formerly held by European-American women. Women moved from their prewar jobs because of better working conditions or higher pay.28 Employment figures from the Cleveland Womanpower Center demonstrate that job opportunities for women of African and European descent increased during World War II. Near the end of the war, in September and October 1944, Cleveland's Womanpower Center referred as many AfricanAmerican women to jobs as European-American ones, and in some weeks found more jobs for women of African descent than European ancestry. For example, during the week of October 23, 1944, the CWC referred 215 European-American women and 263 AfricanAmerican women to employment. A likely explanation is that by 1944, with many EuropeanAmerican women already in the workforce, African- American females were finally being sought for employment. From January 1943 to April 1944, 91,300 women secured jobs in the city, but employers still needed 33,000 more female workers. By September 1944, female employment gains were apparent with over 200,000 women working in Cleveland war plants, compared to 127,000 female industrial workers in 1940. The unemployment rate for women decreased to 14 percent in 1944, from 27 percent in 1943. Cleveland African-American women's employment doubled from five out of 100 workers in September 1942, to eleven out of 100 workers by July 1945.29

In 1943, the Cleveland Call and Post, the city's African- American

Reports,

Box 3205, Entry 272; "Organization of Womanpower Committees," Memoranda to M.

A. Clark from J. K. Johnson, August 31, 1943, Box 2466, Entry 269, WMC Records.

27. "Minutes of the

Womanpower Committee," March 17, 1943; September 25, 1944; October 4, 1944~

October 23, 1944, Series V, Reel 14, Fol 97, Consumers League of Ohio Records,

WRHS.

28. Harris, Out

to Work, 219, 279; Mary Elizabeth Pidgeon, "Changes in Women's Employment

During the War," Special Bulletin No. 20, Women's Bureau (Washington,

D.C., 1944), 8. See also Anderson, "Last Hired, First Fired: Black Women Workers

During World War It," 82-97.

29. "Minutes of the

Womanpower Committee," October 4, 1944, November 1, 1944, Series V, Reel 14,

Fol 97; "Labor Supply Statement of the Cleveland, Ohio Area," March 27, 1943,

Series V, Reel 14, Fol 97; "Report on Women Workers in the Post-War Period,"

September 20, 1944; "Minutes of the Womanpower Committee," November 1, 1944,

October 31, 1945, Series V, Reel 14, Fol 97, Consumers League of Ohio Records,

WRHS.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

156

newspaper, noted that a "steady stream" of men and women of African descent entered employment in government and private businesses. The newspaper declared that "Negro labor in American industry has been markedly improved by the war."30 Despite the optimistic predictions by the Call and Post, classified employment advertisements reveal that the majority of jobs available to African-American women remained those of hotel maids, laundresses, and charwomen. Many times, barriers of race, class, and gender militated against other employment opportunities for African- American females in defense and non-industrial jobs. Industries often hired African- American women only as a last resort or not at all.31

The CWC also attempted to recruit women workers by bringing the Womanpower Center to them. It sponsored a door-to-door canvass during 1943 in Euclid, Ohio, a predominantly working-class suburb, and made inperson attempts to register women for the war effort. An industrial center along Lake Erie on the eastern border of Cleveland, with a population of 17,866, Euclid placed second to Cleveland in the area in important industrial production. The home of thirty-five war factories, the suburb hosted a Thompson Aircraft plant (TRW, Inc.), which became Cleveland's largest employer with a work force of 21,000.32

The CWC's enlistment campaign in particular targeted Euclid housewives for employment. Financed by local industrial and business establishments, ten trained canvassers interviewed 1,000 unemployed Euclid women to determine their availability for war work. The WMC considered the canvass experiment "very aggressive," yet, as of March 1, 1944, women constituted only 31 percent of the employees in twenty-one of the principal companies in Euclid.33

Civilian Service Jobs Campaign

In addition to these recruitment efforts, the CWC also sponsored enlistment drives for women to fill civilian service jobs. By 1943, the service sector desperately needed workers for jobs vacated by working

30. Cleveland Call and

Post, January 9, 1943.

31. Cleveland

Call and Post, 1943-1945, On the "double discrimination" black women faced

in employment during World War II, see Anderson, "Last Hired, First Fired, 83-84,

idem.; Wartime Women, 36; McArthur, "From Rosie the Riveter to the Feminine

Mystique," 12. On employment of black women in Cleveland during World War II

see, Kimberley Phillips, "'Heaven Bound': Black Migration, Community, and Activism,

Cleveland, 1915-1945," (Ph.D diss., Yale University, 1992), 287-90.

32. Van Tassel and

Grabowski, eds., Encyclopedia, 1073; "Brief Report of the Committee on

War Services in the Euclid Sub-Locality of the Cleveland, Ohio, Labor Market

Area., May 12, 1944, Box 2492, Entry 269, WMC Records.

33. Ibid.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

157

VE Day (May 8, 1945): Employees of Thompson Products

sing the National Anthem.

(Photo courtesy Cleveland State University Library, The Cleveland Press Collection.)

class employees transferred to war positions. Of the two campaigns, the CWC had more favorable results with the civilian service undertaking.

At the beginning of the war, the WMC's first priority for worker placement concerned jobs in essential industries. The WMC classified businesses as either essential or nonessential: Essential businesses included defense industries, while nonessential establishments included civilian services in restaurants, hospitals, hotels, department stores, laundries, and dry cleaners. The WMC favored essential businesses, giving them government contracts, allocating to them necessary workers, and refraining from drafting their employees into the armed forces. Nonessential civilian service businesses suffered personnel and financial losses, as recruitment campaigns targeted their female workers to fill positions in higher-paying war jobs categorized as essential. Women often abandoned traditional female occupations to switch to war industries, where they could earn an average 40 percent higher pay.34

34. Judith Freeman Clark, Almanac of American Women in the Twentieth Century (New York, 1987), 8 1.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

158

The success or failure of a business often depended on its WMC classification. Thousands of service businesses closed their doors forever for the lack of female workers. In Cleveland in December 1942, for example, more than 1,000 businesses did not renew their licenses because of worker shortages. The Cleveland WMC "predicted that civilians should be prepared to receive less service" as "hundreds of businesses" closed or limited their services drastically owing to the "manpower pinch."35 In the first three months of 1943, 564 out of 2,804 Cleveland restaurants closed, largely due to lack of personnel.36

By 1943, the WMC discovered that essential war work constituted "too narrow" a concept and that it had directed "too little attention" to the role of civilian service jobs in the total war effort.37 In addition to the essentials of "equipping the army" to fight the war, America began to realize the equal importance of maintaining the "health and vitality" of the homefront workers to ensure that the manufacturing of war goods continued.38

The scarcity of service workers also arose at a time when civilians demanded more goods and services. American entrance into the war had finally ended the Great Depression by providing full employment and high earnings, and the United States entered the "longest period of economic growth in its history."39 By the summer of 1943, people had money to spend because some companies had suspended the manufacturing of such consumer products as cars and appliances, and they sought alternative ways to spend money on items and luxuries that they had done without during the Depression.40

Dining out, an increasingly popular form of recreation, increased the demand for waitresses. Women workers, who now had less time for meal preparation, increased buying power, and fewer domestic servants, patronized restaurants in greater numbers than before the war. Typically 25 percent of the public dined out once a week and another 25 percent dined out once a month or once every other month. Department stores also flourished with the average purchase price rising from $2 in the prewar

35. Cleveland Press,

December 3, 1942.

36. "Application for Determination of Locally Needed Activities," Box 3252,

Entry 274, WMC Records; Cleveland Press, April 3, 1943.

37. Mary Robinson, "War Workers in Two Wars," Monthly Labor Review (October,

1943), 666.

38. "What is this Manpower Problem?" Pamphlet, Series V, Reel 14, Fol

97, Consumers League of Ohio Records. WRHS.

39. Thomas, Riveting and Rationing in Dixie, 81.

40. John Morton Blum, "V" Was For Victory: Politics and American Culture

During World War II (New York, 1976), 96.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

159

period to $ 10 during the war.41 Openings for store clerks thus rose along with those for restaurant help.

By the summer of 1943, war production had slowed because of worker fatigue, absenteeism, and high turnover of female workers. Women working forty-eight-hour weeks needed to leave theirjobs early to stand in long lines to complete domestic errands. Employing more civilian service workers in laundries, dry-cleaning establishments, grocery stores, and restaurants would facilitate shopping for war workers and enable them to return to their jobs faster. More importantly, increasing the employment base might prevent area businesses from permanently closing their doors.42

To address the increased need for service workers, the WMC and the Office of War Information (OWI) sponsored a "Women in Necessary Services" nationwide publicity campaign during September 1943. The effort, which purported to "salute and recruit" women workers in more than 100 low-status, low-paying everyday civilian service jobs, included three weeks of national radio commercials, special news releases, magazine articles, and advertisements, along with department store tie-ins of appropriate window displays. The WMC released to local theaters a special movie short, The Glamour Girls of 1943, to romanticize the unglamorous jobs required for the war effort, and a special insignia of an upraised torch with the inscription "Women War Workers" identified the campaign.43 "America at War Needs Women at Work," the supportive literature stated, "in thousands of apparently hum-drum jobs" in stores, restaurants, offices, laundries, hospitals, child-care centers, bus and streetcar companies, banks, public utilities, and many other businesses.44 Admittedly, low pay, monotony, and bad working conditions associated with jobs in the service sector made these positions seem relatively undesirable but, the campaign stressed, any job was "patriotic and necessary" to the total war effort.45

The WMC directed this campaign at a specific audience. Namely, it was designed to "induce many from the still large reserve of non-employed housewives without small children" to respond. It also

41. Campbell,

Women at War With America, 181; U.S. Bureau of the Census, "Occupational

Trends in the United States 1900-1950," Working Paper #5 (Washington, D.C.,

1958), 576; James R. Green, The World of the Worker: Labor in Twentieth Century

America (New York, 1986),189; Allan M. Winkler, Home Front USA: America

During World War II (Arlington Heights, Ill., 1986), 34.

42. National Manpower Council, Womanpower, 154.

43. Straub, "Women in the Civilian Labor Force," 210.

44. Ibid., 209, Robinson, "War Workers in Two Wars," 666.

45. Honey, Creating Rosie the Riveter, 39-40; Straub, "Women in the Civilian

Labor Force," 2 10; Robinson, "War Workers in Two Wars," 666.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

160

tried to "appeal to the husbands" of these women to allow them to work for the war effort. Primarily targeted were EuropeanA meri can, middle-class women over forty years of age. Previously, these women had not entered paid employment but had instead rendered similar services in volunteer work, at hospitals, churches, and canteens. The CWC hoped that patriotism plus profit would motivate middle-class women-as yet unmobilized–to work for the war effort.46

As part of the national publicity campaign, the WMC and the OWI sponsored a National Magazine Competition to urge women to take civilian service employment. All of the nation's magazines using pictorial covers were asked to devote the cover of their 1943 Labor Day issues to a painting, drawing, or photograph of a woman or women engaged in some sort of essential civilian job. All told, 191 magazines participated and the WMC presented awards to winning covers.47

Norman Rockwell designed one of the most famous covers for the Labor Day 1943 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Rockwell had created a "Rosie the Riveter" cover for the Post's 1943 Memorial Day issue in which he depicted Rosie in worker's coveralls doing a "man's job," sitting smugly on top of a copy of Mein Kampf" with her rivet gun across her lap and the United States flag in the background. For the Post's national magazine competition entry to promote civilian service jobs, Rosie now wore the flag in the shape of coveralls, dashed off to do a 11 woman's job," and replaced her rivet gun with a slew of pails, mops, and brooms.48

As part of the "Women in Necessary Services" campaign, women's magazines printed related stories and articles in their September 1943 issues which reinforced the need for women to enter civilian service employment. In an interview with Margaret A. Hickey, Chairperson of the Women's Advisory Committee, published in Independent Woman (a magazine for Business and Professional Women), Hickey stressed the main points of the campaign, calling the jobs "unexciting" but crucial to the war effort. "Of the nearly eighteen million women who will be working by the end of this year," she said, "fully two-thirds will be needed in civilian trades and services."49

46. Robinson,

"War Workers in Two Wars," 666; Straub, "Women in the Civilian Labor Force,"

216-17. "Suggested Program of Publicity Committee of Womanpower Committee,"

May 27, 1943, Cont 1, Fol 16, Wing Family Papers, WRHS.

47. "Women in Necessary

Service Employment," New York Museum of Modern Art (October/ November

1943), 18; P.D. Fahnestock, "National Publicity and Promotion Campaign for Women

Workers in War Industries- August 30 to October 4, 1943," 2, July 20, 1943,

Cont 1, Fol 16, Wing Family Papers, WRHS.

48. Covers, Saturday

Evening Post, May 29, 1943, and September 4, 1943.

49. Gladys Gove,

"We Sing of Unsung Jobs," Independent Woman (September, 1943), 269.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

161

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee launched an intensified women's recruitment campaign on August 30, 1943, to coincide with the national publicity campaign. As in other locales, Cleveland theater owners agreed to show The Glamour Girls of 1943 film and to decorate their lobbies with posters on the theme "Do the Job He Left Behind." The CWC also displayed some 5,000 posters and passed out 100,000 pamphlets and stickers throughout the city bearing the address of the Cleveland Womanpower Center.50 The CWC aimed to place 3,500 women in essential services in Cleveland, and the intense publicity resulted in a "very effective" enlistment drive. At the end of five weeks, the CWC had referred 5,209 women to work in civilian businesses.51

The "Women in Necessary Service" campaign had long-range effects as well. Soon after the drive ended, area restaurants exerted "considerable pressure" on the WMC. They lobbied for categorization as "locally needed" businesses. Locally needed businesses had to prove that they performed services essential to the health and welfare of the population. The Northeast Ohio Restaurant Association prepared a statement, dated October 11, 1943, on the reasons that area restaurants should be so classified. The report emphasized that restaurants served an "important section" of the population, such as Armed Service and war industry personnel. Additionally, facing a loss of workers to essential businesses, restaurants would have to reduce their operating hours and lower their standards of sanitation, which endangered public health.52

To demonstrate to the WMC that Cleveland restaurants would act as serious war industries if awarded locally needed status, the restaurants eliminated all niceties. They removed special preparation items from their menus, reduced linen service, and practiced stringent conservation to prevent unnecessary waste. These efforts did not go unnoticed, as on November 5, 1943, the WMC granted most of the restaurants in the Cleveland area locally needed status.53

As soon as the WMC granted Stouffer Restaurants of Cleveland, known for serving high-quality food, its new classification on November 26, 1943, Stouffer's circulated brochures to publicize the event: "Yes, the government now declares that restaurants are a direct factor in winning the

50. Memoranda

to R. Meier from P.D. Fahnestock September 2, 1943; Memoranda to L. Appley from

R. Goodwin, July 28, 1943; Both in Box 3205, Entry 272, WMC Records.

51. Memoranda, "Current Campaigns and Special Programs," March 4, 1944, Box

3205, Entry 272; Letter to K. Halle from R. Goodwin, March 30, 1943; Both in

Box 2453, Entry 269, WMC Records.

52. Ibid., Memorandum to Brig. Gen. Frank J. McSherry from R. Goodwin, April

3, 1943, Progress Reports, Box 3205, Entry 272, WMC Records.

53. Ibid., Progress Report, December 17, 1943, Box 3252, Entry 274, WMC Records.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

162

The Tourquoise Room at Stouffer's, 1945. (Photo

courtesy Cleveland State University Library, The Cleveland Press Collection.)

war! ... It also confirms our long time conviction that restaurant work is war work and of No. 1 importance."54

Although Stouffer's overstated its importance to the war effort, in fact the locally needed label meant just that, and more and more businesses convinced the government that they deserved war industry status as essential to the war effort. A major problem arose when the WMC classified countless Cleveland businesses as locally needed, necessitating a "continuous campaign" by the CWC to recruit workers for all types of war work.55

With so many businesses categorized as locally needed, the Cleveland WMC and the CWC could not stay abreast of labor demands in essential war activities. Additional worker shortages appeared when the WMC closed in-migration to the Cleveland area for an experimental sixty-day period beginning September 1, 1943, because of an "acute" lack of

54. "Food,

Jobs ... Essential," Stouffer Restaurants Pamphlet, Box 3252, Entry 274,

WMC Records.

55. Memoranda "Current Campaigns and Special Programs" March 4, 1944, Box 3205,

Entry 272, WMC Records.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

163

housing. The U.S. Government attempted to fill the 35,000 housing applications in the Cleveland area in part by leasing a forty-five-acre tract of land on the city's near west side for a 500-trailer-home park. It also built permanent housing projects, such as duplex homes near Cleveland's airport. However, these efforts satisfied fewer than half of the housing applications.56 Due to these and other factors, on December 1, 1943, Cleveland received a Group I "critical manpower shortage" rating. The Cleveland WMC urged workers to enter "necessary activities," but the large number of essential businesses made it difficult to determine which were the most necessary to the war effort.57

The Cleveland WMC needed new strategies to address the problem. For starters, it lifted the ban on in-migration. The CWC employed marathon recruitment campaigns and Victory Shifts. During 1943, the Women's Bureau had recommended Victory Shifts, the popular term for part-time employment in war plants, to increase productivity. Part-time employment allowed a more "complete" utilization of workers while at the same time allowing working women time for household duties.58 Victory Shifts, perhaps predictably, met with success only in the service industries that had traditionally relied on part-time help.59

Civilian Service Mobilization Failure

In spite of its intensive efforts, the CWC achieved mixed results. It never reached the recruitment quota of 60,000 women that the WMC had estimated the Cleveland area needed for effective mobilization. Social and economic factors played a part in this failure. Of the 800 or more women who visited the Womanpower Center each week, only half secured jobs for the duration of the war. Many women never applied for numerous unappealing jobs because they considered them unrewarding. Throughout the war, 1,500-2,000 jobs classified as female positions (industrial and service jobs) remained vacant in the Cleveland area. Another problem was that many women also quit their jobs before earning $500, to remain eligible dependents on their husbands' income tax returns.60

56. Rose,

Cleveland, 1015; Memoranda to L. A. Appley from R. Goodwin, August 31,

1943, September 8, 1943, Progress Reports, September, 1942-December, 1944, Both

in Box 3205, Entry 272, WMC Records.

57. Cleveland Press, December 1, 1943.

58. For a more complete study of part-time employment see "Part-Time Employment

of Women in Wartime," Special Bulletin No. 13 of the Women's

Bureau, U.S. Department of Labor, (Washington, D.C., 1943), 2.

59. National Manpower Council, Womanpower, 156.

60. Wurzbach, "60,000 Women War Workers," "Minutes of the Womanpower

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

164

The CWC relied heavily on patriotism as a prime motivator to recruit women for war jobs, but patriotic zeal could not overcome the ideological and practical obstacles that women here and elsewhere faced. Fortune magazine described these obstacles: "We are kindly, somewhat sentimental people, with strong, ingrained ideas about what women should or should not do. Many thoughtful citizens are seriously disturbed over the wisdom of bringing married women into the factories."61 The "consensus that women belonged at home" influenced both women's and their husbands' resistance to entering war work.62 The CWC stated that of all the problems in recruiting women, the most perplexing was that a "large number" of women were "still at home" and "not yet convinced of their individual responsibilities toward winning the war."63

Large Cleveland war plants also "bungled their handling of women employees," which led to high employment turnover for women. According to a status report by the National WMC, industry often placed female college graduates in monotonous jobs that under-utilized their abilities or they hired housewives without "adequate training." Some employers "rejected extensive government intervention" into their hiring practices and questioned the types of jobs that women could actually perform.64

The WMC's Training Within Industry program attempted to reassure factory employers that the "only difference between training men and women in industry is in the toilet facilities." Program officials cooperated with local schools such as Shaw High School in East Cleveland and Fenn College (now Cleveland State University) to offer women "warm-up courses" in war industry training and to provide factory supervisors the ,'most effective ways" to train women. In one class, a WMC instructor reassured his female students that a drill press was just like a sewing machine and that they just needed to "learn which end of the screwdriver" to grasp.65 Many women did not attend the classes, however, possibly because of such condescending training philosophy. No matter how much effort the CWC and the WMC displayed, they failed to convince many women that labor needs superseded individual barriers. Statistics

Committee,"

October 4, 1944, November 28, 1945, Series V, Reel 14, Fol 97, Consumers League

of Ohio Records, WRHS.

61.

"The Margin Now is Womanpower," Fortune, 27 (February, 1943), 100.

62. Hartmann, The Home Front and Beyond, 19.

63. "Rough Draft- Womanpower in the War and Post-War Periods," April 15, 1943,

2-4, Cont 1, Fol 15, Wing Family Papers, WRHS.

64. Ibid., Hartmann, The Home Front and Beyond, 67.

65. "Rough Draft- Womanpower in the War and Post-War Periods," 2-4, "Minutes

Womanpower Committee of the War Manpower Commission Cleveland Area," February

4, 1943, Cont 1, Fol 15, Wing Family Papers, WRHS.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

165

continually reflected an untapped reservoir of women candidates for war work. Recruitment campaigns failed to motivate some middle-class, middle-aged women despite labor shortages that plagued Cleveland throughout the war.

Despite such unfavorable evidence, the WMC reported that the CWC received a "great deal of favorable publicity in local newspapers" and accomplished "desirable results." Marie R. Wing, CWC member and attorney for the Social Security Board, who eagerly embraced her wartime responsibility, agreed that the Committee represented a "well balanced" entity. The WMC also praised the Womanpower Committee for operating "harmoniously." In addition to their CWC meetings, committee members frequently lunched together to discuss further recruiting and publicity ideas.66

Regional Director Goodwin declared the CWC experiment a "success" and used it as a model for other areas. CWC Chair Schauffler later became an Administrative Assistant to Cleveland WMC Director Edmunds and a Womanpower Committee Consultant on the Regional WMC staff. By October 1944, WMC Region V had implemented womanpower committees in Cincinnati and Lorain, Ohio, and Louisville, Kentucky.67 From all outward indications the WMC appeared pleased with the CWC. Internal WMC literature, however, stressed only that the committees could be "very helpful from a public relations standpoint."68 This statement suggests that the WMC felt the Womanpower Committee effective in gaining publicity for the labor shortage, but ineffective in actual labor recruitment.

Social and economic factors beyond the CWC's control prevented the committee from fully mobilizing the middle-class womanpower reserve in Cleveland. Despite patriotic appeals and training sessions, a segment of the female population remained unconvinced about entering war work.

66. Memoranda

to J. P. Blaisdell from R. Goodwin, Box 2497, Entry 269; "Organization of Womanpower

Committees," Box 2466, Entry 269, WMC Records; Letter from Marie Wing to Charlotte

Carr, March 13, 1943, Cont 1, Fol 15; Letter from Marie Wing to Lena Ebeling,

June 2, 1943, Cont 1, Fol 16, Wing Family Papers, WRHS.

67. Letter to C.

0. Skinner from R. Goodwin, September 20, 1943, Progress Reports, September,

1942-December, 1944, Box 2453, Entry 269, WMC Records. Schauffler received $3,200

per year as Administrative Assistant to Edmunds, the same as Edmunds' two other

male Administrative Assistants. Memoranda to L. A. Appley from R. Goodwin, September

8, 1943, Progress Reports, September, 1942-December, 1944, Box 3205, Entry 272;

"Organization of Womanpower Committees," Memorandum to M. A. Clark from J. K.

Johnson, August 31, 1943, Box 2466, Entry 269, WMC Records; "What is this Manpower

Problem'?" Pamphlet, WMC Region V, June, 1943; Minutes of the Womanpower

Committee WMC, October 4, 1944; Both in Series V, Reel 14, Fol 97, Consumers

League of Ohio Records, WRHS.

68. Ibid.

The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945

166

Traditional views of women's roles and the undesirability of the jobs available affected their choice, along with practical hindrances such as tax concerns. The WMC's mobilization policy of voluntarism, its closing of in-migration in Cleveland, and its generous granting of locally needed status to so many Cleveland businesses further prevented the CWC from attaining its recruitment goals. Cleveland continued as a Group I critical war production city throughout most of the war.69

Indeed, the Cleveland WMC came to realize the importance of women to the total war effort and created a committee composed entirely of women to recruit female workers. Unlike the national WAC that could only suggest policies to attract women workers to necessary jobs, the CWC successfully implemented recruitment campaigns that brought women into factory and service jobs for the duration of the war. While the committee did not achieve the WMC's recruitment goal (nor did the WMC achieve its goal of recruiting male workers), it did succeed in permeating gender, race, and class barriers. Middle-class African American and European American Cleveland women worked jointly for more than two and one-half years to attempt to fill the city's desperate need for female workers. Meeting weekly and working daily, these women used genderspecific ideas to attract women to that part of the war mobilization effort which men might overlook. The CWC insisted that the Womanpower Center be located in the city's busiest shopping district where women congregated, and also advertised the center in places where women assembled-beauty shops, retail stores, and club meetings. It broadcast further appeals in radio dramas and publicized them in shopping newspapers to attract women. The committee also worked within and across class lines to rally Cleveland-area working and middle-class women for war work. From March 1943 to November 1945, the CWC referred thousands of women to industrial and service employment, sponsored recruitment campaigns, and endorsed Victory Shifts. The CWC's promotion and enlistment efforts proved a model for other Womanpower Committees across Ohio and the country. The CWC worked within race, class, and gender boundaries to see that women would "Do the Job He Left Behind!"

69. Cleveland Press, August 11, 1945.