Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

BAKER ON THE FIFTH BALLOT? THE DEMOCRATIC ALTERNATIVE: 1932

by ELLIOT A. ROSEN

A study of history's might-have-beens is often more interesting and infor- mative than one would suspect from the bare recital of what happened. For in addition to the zest of narrative it has the delight of speculation. Very often the threads which lead to a great decision are intertwined with other strands which, if they had prevailed, might have brought about an entirely different aftermath. What would have been the consequences for this nation if Lincoln had not met his death at the hands of an assassin early in 1865? What if Wellington's thin red line at Waterloo had collapsed before Bl??cher brought support? What prompted decisions to be made in one way and not in another?

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 273-277 |

BAKER ON THE FIFTH BALLOT? 227

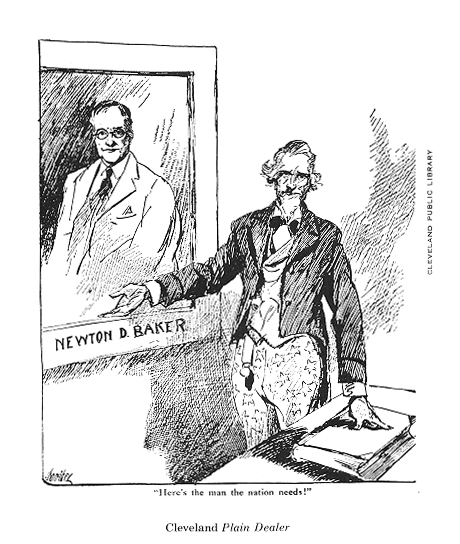

If the powers and personalities at the

Democratic convention at Chicago

in 1932 finally had not reached a

decision on the fourth ballot to nominate

Franklin D. Roosevelt, it is certain

that the Roosevelt strength would

have crumbled soon and someone else

would have won the prize. It is

the thesis of this article that Newton

D. Baker would have been the man

chosen and Ohio would very probably have

added another to her long list

of presidents.1

If the electorate had chosen Baker in

1932, the course of our nation's

history would have been radically

different. There would have been no

New Deal. The personnel of the new

administration would have been of

another sort. The attack on the

depression would have taken another course.

The Democratic party for years to come

would have been oriented to a

quite different philosophy.2 Clearly the

Jeffersonian-internationalist wing,

represented by figures such as Cordell

Hull, would have been more content

under Baker's leadership. Also, the

Democratic party would have been

more conservative in its domestic

policies and more internationalist-minded

in its foreign relations.

Newton D. Baker of Ohio was nationally

known in 1932 principally

because of his former association with

two of the luminaries of the Progres-

sive era, Tom L. Johnson, reform mayor

of Cleveland, and President Woodrow

Wilson. As Cleveland's city solicitor,

from 1902 to 1912, he was one of

Johnson's key aides in the famous street

railway controversy, which had

as its goals municipal control and lower

fares. He aided also in the effort

to derive additional revenue for the

city by reassessment of railroads and

utilities. As mayor of Cleveland

(1912-1916), after the defeat and death of

Johnson, Baker won the admiration of

Progressives for his personal integrity

and the maintenance of Cleveland's

reputation as the nation's best governed

city. Particularly appealing to radical

progressives was Baker's establish-

ment of a municipally owned power plant.

When Woodrow Wilson's Secretary of War,

Lindley M. Garrison, resigned

early in 1916, as a consequence of the

President's concessions to the

Congress in the famous preparedness

controversy, Wilson tapped his former

Johns Hopkins student for the post. In

the course of five years' service,

until 1921, Baker, who came to his post

with a reputation as a progressive

pacifist, made the same national

reputation as Secretary of War for

efficiency and integrity that he had

enjoyed in Cleveland. In the process

he also became one of Wilson's most

trusted advisers.

Baker returned to Cleveland in 1921 to

head the distinguished law firm

of Baker, Hostetler and Sidlo.

Throughout the 'twenties he crusaded for

American commitment to the League of

Nations as the best hope to

forestall another war. Particularly well

known was his moving speech

before the Democratic National

Convention of 1924 in which he attempted

without success to secure endorsement by the party of

Wilson's advocacy

of United States membership in the

League. Though he lost the battle,

his emotional address in behalf of

those, including Wilson, who had died

for a principle enhanced his stature and

cemented his image as heir apparent

to the mantle of the former president.

228 OHIO HISTORY

In the 1920's, however, it was contended

by some people that the once-

progressive disciple of Tom Johnson and

Woodrow Wilson was growing

more conservative. They observed that

his Cleveland law firm was asso-

ciated with a large corporate law

practice, sometimes as a representative

for utilities. And when he served a term

as president of Cleveland's Chamber

of Commerce, as we shall see, he was an

exponent of the open shop. But

those who knew him well assert that

fundamentally he had not changed.

Raymond Moley, Roosevelt's principal

adviser in 1932, coincidentally had

also made his early reputation in

Cleveland and knew Baker intimately,

particularly through association in

several civic enterprises in the lake city

after the first World War. Moley

recalled that the "progressive crowd that

criticized him in Cleveland" had

failed to observe that Baker not only

knew and feared the consequences of war

but feared also excessive centraliza-

tion of government. "I heard him

speak more than once in Cleveland,"

Moley remembered, "and he was

always portraying the terrible circumstances

that would attend the next war." At

the same time "I heard him say once

that it is better to permit a country .

. . to make mistakes and rue them,

then to restrict and control them by any

arbitrary power."3

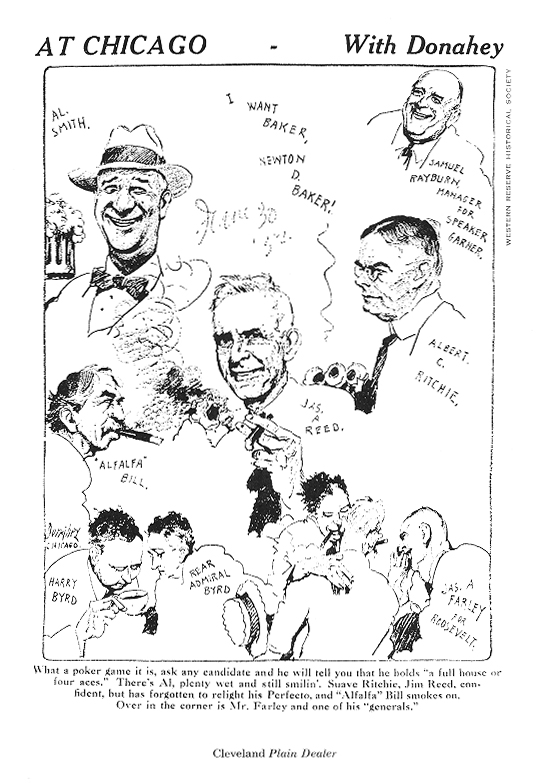

Newton D. Baker's strength within the

Democratic party, gathered at

Chicago in 1932, was pervasive rather

than intensive. Baker had the support

of the intellectuals, among them Walter

Lippmann, William E. Dodd,

Douglas Southall Freeman, George Fort

Milton, Allan Nevins, and Adolf

A. Berle. Lippmann's famous declamation

on Roosevelt's lack of conviction

and his lack of qualification for the

presidency is well known.4 But less often

discussed is the fact that the columnist

was an avid partisan of Baker's

candidacy5 and that intellectuals, old

Wilsonians, businessmen and others

who knew Franklin Roosevelt in the Navy

Department days generally

regarded the then New York governor in

the same unfavorable light as

did Lippmann.6 "Lippmann,"

Raymond Moley remembers, "was putting into

words and publishing what was said in

every private club in New York."7

Roosevelt himself, though angered by

Lippmann's Herald Tribune article,

held Baker in great esteem. "....

Newton," he wrote Josephus Daniels,

"would make a better President than

I would."8 Daniels agreed that Baker

was the party's ablest man.9

Adolf A. Berle, a Baker supporter,

typified Democratic sentiment at

Columbia University, the principal

source of Franklin D. Roosevelt's Brains

Trust. Berle, a member of the Columbia

University Law School faculty,

an attorney and a specialist in

corporate organization and finance, in com-

pany with the noted Columbia University

historian, James T. Shotwell,

persuaded a group of attorneys, early in

1932, to write an open letter to

Baker urging him to declare his

candidacy.10 Nevertheless, Berle's recruit-

ment to membership in the Brains Trust

occurred in April 1932 and was the

work of Raymond Moley, Professor of

Public Law at Columbia and head

of the Brains Trust, an unofficial group

organized to advise Roosevelt on

the formulation of campaign issues and

ideology. Moley, in fact, recalls

that the general task of recruitment of

scholars to advise Roosevelt was

not an easy one, since the essential

division among Democratic members

BAKER ON THE FIFTH BALLOT? 229

of the Columbia University faculty,

including Berle, was between Baker,

favored by the conservatives, and Norman

Thomas, the Socialist, favored

by the liberals. "When I went to

Berle's office at the Columbia Law School,"

Moley recalls, "to recruit him for

our group, he said, 'I have another candi-

date.' Then I said that doesn't matter.

We need your specialized knowledge.

He then accepted."11

Baker was also the choice of eastern

conservatives in the business and

banking community who, because of their

economic interest, were inter-

nationalist in their foreign outlook and

conservative in their domestic

philosophy. These included A. Lincoln

Filene of Boston; Owen Young,

president of General Electric; John W.

Davis, Frank Polk, Thomas Lamont

of J. P. Morgan & Company; Lee

Olwell, vice-president of the National

City Bank of New York; Melvin Traylor, a

Chicago banker; Robert Wood-

ruff, president of Coca Cola; Nathan

Straus and B. Howell Griswold of

Alex Brown & Sons, Baltimore

bankers; Eugene Untermeyer of Guggenheim,

Untermeyer & Marshall; and Norman

Davis, also a member of the inter-

national banking community. The

philosophy of this group was perhaps

best typified by David F. Houston,

Woodrow Wilson's Secretary of Agri-

culture and in 1932 president of the

Mutual Life Insurance Company.

Houston decried increasing dependence of

the people on the federal treasury.

Nor did he sympathize with efforts in

Washington aimed at the relief of

the farmer.12 Thus, Baker, in

a campaign, would have been stronger than

Roosevelt not only with conservative

Democrats but with conservative

eastern Republicans as well.13

As has been mentioned, Baker was heir

apparent to the mantle of

Wilsonian internationalism especially

because his brilliant and impassioned,

if unsuccessful, speech in favor of

League endorsement at the 1924 Demo-

cratic convention had cemented the

image.14 Byron R. Newton's feeling

for Baker was typical of many of the old

Wilson crowd:

Few men are born nine feet tall, and few

men are born with the

breadth and strength to sacrifice

themselves to the advantages of the

great cause or the betterment of their fellow

men. Usually these chaps

died in childbirth or were burned at the

stake quite early in their

career, but when they do survive the

burning and the childbirth they

leave history and milestones behind

them, because, like yourself, they

have no illusions, no vanities, no fears

-- just a steadfast gaze at the

road ahead.

That was the one quality in Woodrow

Wilson that in my eyes lifted

him above all other men. In my life I

had seen much of other men whom

the world called great, but Wilson was

the only one of them all, who

if he thought necessary to the

achievement of some great end, would

sacrifice himself and his political

future to the betterment of mankind.

Such men are nine feet tall, very

scarce, but in the great plan of human

life it seems to be necessary for one to

appear now and again to wallop

the floundering mob into shape.15

For Byron R. Newton and many of the

other Wilsonians, Baker also

possessed these qualities and would have

made an excellent candidate for

the presidency. Indeed, this was the

opinion of the former President's

widow herself.16 In the words

of another supporter, "I cannot abandon the

230 OHIO HISTORY

conviction," Norman Davis wrote

Baker, "that our only hope is through

you, and that it is not too late even

now for you to do it."17 And after

several rebuffs in primary elections in

early 1932, even the venerable Colonel

House, an ardent Roosevelt supporter,

told Robert Jackson, "I think we

had better be thinking of a second

choice." House indicated to Jackson,

who was not receptive, that Baker was

his alternative to the New York

governor.18

In the field of news media an imposing

array of writers and editors, in

addition to Lippmann, supported Baker's

candidacy. These included John

Stewart Bryan, editor of the Richmond News

Leader; Mark Watson, Mark

Sullivan, and Fred I. Kent of the

Baltimore Sun; Roy Howard of the Scripps-

Howard chain; Julian Mason, editor of

the conservative New York Evening

Post; the Cleveland Plain Dealer; the Cincinnati Enquirer;

the Des Moines

Register-Tribune; H. V. Kaltenborn and George Creel. If some did not

openly endorse Baker, as was the case

with the editors of both the Baltimore

Sun and the Scripps-Howard papers, endorsement of Alfred E.

Smith

instead was regarded as a

"cover" until the propitious moment.19

But Baker's greatest political strength

lay with those conservative ele-

ments in the Democratic party who

controlled its machinery and who

wanted to forestall the nomination of

Franklin D. Roosevelt. Whereas

Roosevelt and his principal adviser,

Raymond Moley, saw in the 1932

campaign an opportunity to present a

liberal economic program as an

alternative to that of the Republican

party, Alfred E. Smith, John Raskob,

chairman of the Democratic National

Committee, and Jouett Shouse, chair-

man of the party's National Executive

Committee, feared a takeover by

the Progressives and liberals of the

party they controlled. With Roosevelt

as nominee, Moley wrote an old Cleveland

friend, "we can have a real align-

ment between liberals and

conservatives."

The thing that is hardest to me is the

persistent propaganda against

him [Roosevelt] by interested people,

particularly the power interests

who have not been friendly to his ideas

of governmental power control

in New York. In the near future we may

expect these elements of the

Democratic Party who want to be as near

like Hoover as possible to

concur on some candidate like Baker or

[Owen D.] Young. This, I

believe, will be the final outcome of

the Smith opposition.20

Cordell Hull was equally concerned that

the "Smith-Raskob-Du Pont

group, which according to my belief

favors a virtual merger of the two

old parties except as to

prohibition," would attempt to kill off Roosevelt

and in the process destroy the

Democratic party after 1932.21

John J. Raskob, an intimate of Pierre S.

Du Pont and vice-president of

General Motors, summarized the views of

the Smith group in a radio

broadcast in the Lucky Strike series in

May, 1932. Paraphrasing Jefferson's

first inaugural, Raskob advocated

frugality in government, states' rights,

the taking of government out of

business, relief of business, relief of business

from unreasonable governmental

restrictions, voluntary cooperation, elimina-

tion of governmental attempts at price

fixing, presumably in agriculture--

in general a return of authority to the

states. Fundamentally, the Raskob-

Smith-Shouse program, aside from its

much-vaunted emphasis on prohibi-

BAKER ON THE FIFTH BALLOT? 231

tion repeal, advocated a central

government even more conservative in

economic philosophy and policies than

that of the Hoover administration.22

One week after the Democratic

convention, in a letter to Jouett Shouse,

Raskob lamented that a "crowd of

radicals" -- Roosevelt, Huey Long,

Hearst, McAdoo, and Senators Wheeler and

Dill -- had taken over the

party, as opposed to the fine

conservative talent represented by Harry

Byrd, Smith, Carter Glass, John W. Davis, James Cox,

Pierre S. Du Pont,

and Governor Ely of Massachusetts.23 It

is significant to note that all of

the latter group would soon become

bitter opponents of the New Deal

and some the leaders of the American

Liberty League.

It is too simplistic to argue that the

failure of Franklin D. Roosevelt's

diverse opposition to coalesce

successfully around Baker as the nominee

was the result of a lack of interest on

Baker's part or Al Smith's reluctance

to part with his delegate strength at

the convention.24 Negotiations between

the Smith and Baker camps had been going

on for nearly a year and while

Baker was indeed hesitant, because of a

heart attack suffered during the 1928

campaign, he was nevertheless willing to

be drafted. Baker's reluctance,

however, was not the paramount

consideration in the failure of the stop-

Roosevelt movement. Rather, the failure

can be accounted for by Baker's

alleged conservatism in domestic affairs

and his internationalism in foreign

affairs in contrast to the image of

Roosevelt as a progressive and a nationalist.

In 1931 Alfred E. Smith and the two men

he had installed at the head

of the machinery of the Democratic

party, Raskob and Shouse, were in

search of a candidate who could head off

Roosevelt. Smith may have had

vague hopes at times that the party

would reward him with another nomina-

tion. But the record shows, contrary to

his public statements, that he was

too astute a politician to believe that

he could overcome in 1932 at Chicago

the opposition of the southern and

western Democrats who hungered for

victory after twelve years in the

wilderness. He was a Catholic, a New

Yorker, a Tammany product and a dripping

wet. For many Democrats,

including a host of Smith admirers, this

combination of liabilities represented

too great a gamble during a year of

otherwise certain victory. Smith and

his intimates knew it.25

In September 1931 Smith, Raskob, and

Shouse settled upon Newton

Baker as the man to stop Roosevelt's

march to the nomination. Shouse, in

fact, informed Ralph Hayes, Baker's

"Louis Howe,"26 that if Baker "would

consent to be supported, 'Z' [Smith]

will not only eliminate himself but

will throw to you every particle of

strength he can muster." Mrs. Belle

Moscowitz, Smith's most trusted adviser,

told Hayes candidly that her

choice was still Smith "but that if

she couldn't have her man -- and such

a choice did not appear to be in the

cards -- she much preferred ours."

And Raskob, in turn, offered to free

Baker of any obligation to him in the

event he was nominated and elected,

going so far as to offer his resignation

as head of the Democratic National

Committee.27

These early September conferences

between Hayes, Shouse, Raskob, and

Belle Moscowitz resulted in a meeting of

Shouse and Hayes with Baker at

the Willard Hotel in Washington late

that month.28 Baker convinced Shouse

232 OHIO HISTORY

that he would not actively seek the

nomination and would consent to run

only if drafted. Josephus Daniels and

John Stewart Bryan, prominent

southern newspaper editors, had the same

understanding.29 Baker was

unwilling to become an avowed candidate and never did.

But his supporters

never gave up and had no reason to.

Baker, after all, submitted to a

physical examination, as did Roosevelt,

was pronounced fit enough for a

limited campaign, and negotiated for

months with the Smith entourage

behind the scenes.30

Jouett Shouse came away from the

Washington meeting with Baker

"greatly heartened" and

determined to carry out a strategy conceived at

the conference that became the keystone

of the "stop-Roosevelt" move-

ment; encouragement of an "open

convention" -- subsequently advocated

by Baker, Shouse and others -- made up

of uninstructed and native-son

delegations and bound by the two-thirds

rule.31

It would seem that Baker's January 1932

declaration on the League of

Nations, generally regarded as a retreat

from his earlier position, and Al

Smith's announcement of his candidacy on

February 8, 1932 were a part

of this larger

"stop-Roosevelt" strategy. Belle Moscowitz had told Ralph

Hayes at a meeting at Smith's Empire

State office in mid-November 1931

that Smith's feeling toward Baker

"is one of complete cordiality; his only

inquiry is as to whether your militant

identification with the League might

act as a popular deterrent if pressed

too vigorously in the campaign."32

Mrs. Moscowitz was informed by Roy

Howard, of the Scripps-Howard

newspaper chain, of Baker's statement

before it was issued to the press

and she was quite pleased with it. Thus

from the time of Smith's formal an-

nouncement through the spring of 1932

there is ample evidence that every

known confidant of Smith was either an

avowed Baker enthusiast, such as

Jouett Shouse, Charles Michelson, and

Norman Hapgood, or was in constant

negotiation with Hayes and Baker, as

were Frank Hague, Raymond Ingersol,

and Belle Moscowitz.33 The

evidence of these negotiations is so overwhelming

as to lead to the following conclusions:

1. Baker and Smith were well aware that

open endorsement by Smith

of Baker would be tantamount to a kiss

of death for Baker. Smith shrewdly

decided, therefore, to take as much of

the delegate strength of the Northeast

for himself as he could muster in the

convention in the hope of eventually

entering into an agreement with other

stop-Roosevelt leaders and with

native sons on the selection of a third

person.

2. That this third person would be a

conservative and yet be capable

of binding up the wounds in the party.

3. That, while it is common knowledge

that the Smith forces considered

James Cox, Owen Young, and others in the

spring months, Baker was

finally setttled upon as the choice for

nominee. (Cox flatly refused to run

and Young, as president of General

Electric, stood no chance and withdrew

in May 1932.)

Walter Lippmann, who had access to

Smith, came to this same conclusion

shortly after Smith's announcement of

his candidacy. "It is impossible to

BAKER ON THE FIFTH BALLOT? 233

believe," Lippmann wrote,

"that Smith, who is a great realist . . . expects

to be nominated. He had no illusions

about his election in 1928 and he

can hardly have any now about the

party's willingness to go again through

an ordeal by fire. But that he does not

wish to be ignored, that he believes

he represents a political force, that he

intends to be consulted on the candi-

date and platform is now evident."

It was Lippmann's conclusion that

Smith's followers could do no more than

deadlock the convention and

nominate someone other than Smith and

Roosevelt. That candidate, he

predicted, would be Baker.34

Lippmann's analysis of the situation

seems to be borne out by the follow-

ing events. In mid-February, Mrs. Belle

Moscowitz visited Baker in Cleve-

land. Though what transpired is not a

matter of record, other than the

fact that Smith was highly gratified,

Judge Joseph Proskauer told Jonathan

Daniels at a dinner at Poskauer's home

at about the same time that either

Baker or Governor Albert C. Ritchie

[Maryland] would be an excellent

nominee.35

The last hurdle to a Smith-Baker

coalition, it seems, was Smith's campaign

manager. Frank Hague, boss of Jersey

City, and Ralph Hayes, Baker's

political manager, met at the Biltmore

Hotel in New York on March 31,

1932. Hague indicated that he was

unhappy with Smith's prospects, expressed

a strong dislike for Franklin Roosevelt,

and asserted that only Baker could

stem the Roosevelt tide. "What is

worrying him to distraction," Hayes wrote

Baker the next day, "is that he has

no place to throw the strength he

can command which he regards as being of

more than veto proportions.

You [Baker] are the only official who

can step into the breach, as he sees it."36

Hague and Baker met twice later at the

Willard Hotel in Washington.

"He was gracious," Baker wrote

Hayes, "but wholly impersonal, as was

Governor Smith." Subsequently, when

Hague met with Ralph Hayes and

Norman Hapgood (who, with Dr. Henry

Moscowitz, was Smith's campaign

biographer in 1928) in New York, Hague

agreed to do nothing that would

cause Baker embarrassment (presumably

open endorsement). In the mean-

time, prominent New York conservatives

such as Frank Polk, Nathan Straus,

Jr., and John W. Davis worked on Boss

Curry of Tammany Hall (Curry

was also reluctant to commit himself);

and at a luncheon with Walter Lipp-

mann, Bernard Baruch gave Baker his

blessings.37

On the eve of the Democratic convention

Jouett Shouse's admiration

for Baker became more open. At a mock

Democratic convention at Harvard

University and at other appearances in

Massachusetts late in May, Shouse

asserted that Owen Young and Baker were

the two individuals best qualified

to cope with the depression, a statement

picked up by Boston papers but

not reported in the New York press. It

is interesting to note that Young

had just withdrawn from consideration as

a nominee.38

There were some Baker supporters,

however, who were wary of the

growing identification of their

candidate with the Smith wing of the party.

William E. Dodd, Professor of History at

the University of Chicago and

influential in Chicago Democratic

circles, for instance, believed that Baker

234 OHIO HISTORY

was getting into "doubtful

relationships." And an intimate friend of Baker

and Hayes, retired Supreme Court Justice

John H. Clarke, cautioned that

the Roosevelt camp, in event of a

convention stalemate, would veto any

Smith candidate.39

The ultimate test of this hypothesis

regarding the intimacy of the Smith-

Baker camps can be verified by Smith's

behavior before and at the conven-

tion and will be discussed later.

Smith's tactics at Chicago were neither as

stubborn nor as inept as has generally

been contended. Nor did the con-

vention, on the fourth ballot, secure

Roosevelt's nomination primarily as a

result of Farley's political tactics.

Roosevelt's nomination was finally

secured by issues and by the fear that

Newton D. Baker would be the

nominee if Roosevelt was not chosen.

This observation calls for substantiation.

Newton D. Baker was conservative,

internationalist, and bore the stamp

of Woodrow Wilson. In many respects he

can be compared with another

admirer of Wilson, Herbert Hoover.

Roosevelt, on the other hand, had

already taken the first steps toward his

"New Deal." In the "Forgotten Man"

speech on April 17, 1932 he identified

himself with the downtrodden; at

St. Paul on April 18, 1932 he clearly

associated himself with those who

favored national regulation of public

power; and at Oglethorpe University

on May 22, 1932 he called for planning

of production and distribution. As

a consequence, Roosevelt became the

spokesman of the popular issues of

the day, those issues which appealed to

the lower and middle classes and

to the progressive reformers who sought

fundamental changes in the relation-

ship between government and our society.

Roosevelt was suggesting, even if

somewhat vaguely, alternatives to the

Hoover program; Baker was not, despite

his impressive intellectual endow-

ment. In fact, there is nothing to

suggest that the Ohioan was critical of

Hoover's domestic policies.40 Roosevelt

was the spokesman, too, of a nation-

alistic approach to the nation's

economic problems, later to be dubbed

"intranationalism" as it

crystallized in the 1932 campaign. Alone of all the

presidential aspirants in 1932, he, with

a small band of advisers, was

reexamining the economic, political and

social fabric of the 'twenties. In the

process Roosevelt did more than preempt

the Progressive heritage with its

middle-class support; he went beyond it.

Essentially it was the endorsement of

the "single-issue" Progressives which

brought Roosevelt into the convention

with a majority of the delegate

votes (but not the needed two-thirds).

Indeed, there were also the band-

wagon types -- those who were bigoted

and those who realistically feared

a debacle in the event of a second Smith

nomination and those who found

"magic in the name" as their

primary motive for backing the New York

governor. But an investigation of the

correspondence of the powerful

senatorial Progressives, Republican as

well as Democrat, reveals two facts:

their power ranged far beyond their

immediate states; and most had one

favored program for the relief of the

nation's ills. For Norris, it was public

power and regional development,

federally managed and regulated; for Hull,

reduction of tariff barriers; for

Pittman, remonetization of silver; for Wheeler,

free silver; for Walsh, the St. Lawrence

Seaway as a means of reducing the

BAKER ON THE FIFTH BALLOT? 235

cost of shipping agricultural products

from the plains area. These men were

wedded to the unfulfilled dreams of the

Progressive era; and while many

rationalized their ideas into depression

cures, none had a sophisticated or

integrated approach to the solution of

the nation's woes. Each was aware

of Roosevelt's limitations, but of the

various candidates available they

regarded him as most likely to support

programs they had offered up

unsuccessfully for a decade and more. It

is noteworthy that the New Deal

went far beyond the schemes of the

"single-issue" Progressives of the Senate.

Yet, in other respects, as the record of

the Hundred Days and after shows,

Roosevelt never went far enough to

satisfy most of these early supporters,

particularly when their pet projects

were involved.

As for Roosevelt's strongest political

contender for the nomination,

Baker's strengths in 1932 were at the

same time his very weaknesses. The

principal obstacles to his nomination

lay not in the realm of political tactics

but in his association with the open shop, the utility

interests, and the League

of Nations. At the same time, Baker's

approach to the Great Depression

was that of an internationalist, of the

school of Hoover, Hull, Stimson,

Norman Davis, and Russell Leffingwell.

As I see it [Baker wrote Byron R. Newton

during the 1932 campaign]

the policies of the Republican Party

from 1921 until now have aimed

at political and economic isolation in a

world in which such isolation is

almost impossible and full of peril

where possible. It does not seem

to me that any real progress forward can

be made until an entirely

different theory of our country's

relations to the rest of the world is

adopted. This theory I do not believe

the Republican Party can adopt.

Its commitments to the opposite

philosophy are so deep that any

departure from them would be incredibly

difficult. The Democratic

Party, on the other hand, has at least a

tradition of another kind,

and while it is true that a good many of

our so-called Democrats in

the House and Senate have not behaved

with any conscious adherence

to the great tradition, many of them

have.41

The internationalist point of view had

as its end the achievement of an

enduring world peace and general

economic resuscitation through inter-

national cooperation. Whether the stress

lay in Hoover's aspirations for a

World Economic Conference, or Baker's

identification with the League, or

Hull's advocacy of reciprocal tariff

agreements, the end nevertheless remained

the same, namely, solution of world-wide

economic questions through

international arrangements reached with

United States participation.

In an attempt to mollify those elements

in the Democratic party that

objected to League membership, Baker

made the statement early in 1932

that has been mentioned previously which

seemingly repudiated his earlier

stand on adherence to the League. In

retrospect, it seems to have been a

tactical blunder for it satisfied

neither those who followed his leadership,

which symbolized the Wilsonian dream of

a world order under the League,

nor those who feared that Baker would do

everything possible as President

to bring this nation into the world

organization.42

Baker made his statement on January 26,

1932, when he boarded ship

for a vacation in Mexico. When asked

whether the question of League

membership would come before the

Democratic convention again in 1932,

236 OHIO HISTORY

he replied: "I am not in favor of a

plank in the Democratic national platform

urging our joining the League. I think

it would be a great mistake to make

a partisan issue of the matter." He

did believe that entry of the United

States into this world organization

would come about eventually, but only

after the bulk of the American people

"have had a chance to see the League

in action, and to study its action

enough to be fully satisfied as to the wisdom

of such a course."43

Reactions to Baker's comments on the

League were mixed. Generally

the Wilsonians regarded them as a sad

retreat from his earlier positions,44

though Baker pointed out he had been

moving away from the international

organization since the Democratic defeat

in 1924. The country, he argued,

was not ready for the League in 1932,

not at least until both parties relegated

the issue to the realm of

non-partisanship. From a tactical view, he con-

cluded, the minority party could not

afford the luxury of League endorse-

ment.45 Newspapers, such as

the New York Herald Tribune, interpreted the

statement as an avowal of candidacy.46

Roosevelt evidently felt compelled to go

beyond the Baker statement; in

a speech before the New York State

Grange at Albany, on February 2, he

opposed American participation in the

League. He defended his change of

heart over the course of twelve years by

claiming that "the League of

Nations today is not the League

conceived by Woodrow Wilson." It was

no longer a structure dedicated

primarily to the maintenance of world

peace, but rather a "mere meeting

place" for the discussion of strictly

European national difficulties. "In

these the United States should have no

part."47

Subsequently, Ralph Hayes urged Baker to

make another public state-

ment on the League which would

differentiate his position from that of

Roosevelt. Baker refused: "If there

is any one thing which the course of my

life has taught me, it is that

explanations simply entail more explanations."48

On international debts, too, the two

potential candidates differed sharply.

Baker believed that the entire debts and

reparations system must be

scrapped or at least scaled down

sharply. Roosevelt, in his Albany speech,

took a firmly nationalistic stance.

"National debts," he claimed, "are 'debts

of honor'; . . . no honorable nations

may break a Treaty in spirit any more

than they can break it in letter; nor,

when it is a debtor, may repudiate

or cancel a national debt of

honor."49

It is difficult to determine which man

suffered more from the exchange,

particularly in regard to the League

statements. Whereas Baker supporters

were dismayed by his cautious retreat,

Roosevelt supporters, particularly

the powerful Washington "inner

circle" of old Wilsonian internationalists

who were identified in the 1920's with

the Democratic National Committee,

among them, Daniel Roper, Robert Woolley

and Cordell Hull, were equally

dismayed by the Albany speech which they

regarded as a sell-out to

William Randolph Hearst. Louis Brownlow,

an expert in municipal affairs

and Lecturer at the University of

Chicago, who knew many Democrats

because of past prominence as a

journalist, came away from a visit to

Washington in April with the distinct

impression that the Washington

BAKER ON THE FIFTH BALLOT? 237

group would be pleased if the convention

turned to Baker. Ralph Hayes

had reports from other sources as well

that Hull favored Baker's moderate

position on the League.50 What

he did not know, however, was that Hull

feared even more the possibility of

continued domination of the party

machinery by the "Smith-Raskob-Du

Pont crowd."

Baker's greatest handicap with

Progressives was his identification with

the private utility interests. Judson

King, director of the National Popular

Government League, spread the gospel

concerning Baker's association with

the private power interests in the form

of the New River Case. King, with

the aid of his wife Bertha, made the

organization a full-time occupation in

the years between Wilson and F. D.

Roosevelt, when he with other Pro-

gressives fought a bitter holding action

for the preservation of natural

resources for development in the public

(as opposed to private) interest.

Their chief concern was the promotion of

the public power question,

specifically, government as opposed to

private development of water power

resources, the bulk of which were to be

found in the public domain. And

as a corollary, they constantly

challenged the exorbitant rates and ques-

tionable practices of the private

utilities. In their work, the Kings drew

financial and moral support from

politically powerful Progressives, such

as Senator George W. Norris of Nebraska,

proponent of public ownership

and operation of Muscle Shoals (later T.V.A.); Senators

Smith W. Brookhart

of Iowa, Thomas J. Walsh of Montana,

Edward Costigan of Colorado, and

Bronson Cutting of New Mexico; and old

Bull Moosers, such as Harold

Ickes and Donald Richberg, later

identified with the New Deal. Others,

too, claimed, as did King, that Baker

had "changed his spots" since the

time of Tom Johnson's and his own

administration of Cleveland.51

It was Judson King's contention that the

attempt of the Appalachian

Power Company, a Virginia corporation,

to secure a "minor part" license

for construction of a power dam on the

New River in Virginia through a

suit in the federal courts, if

successful, would establish a precedent leading

to nullification of the Federal Water

Power Act of 1920. Appalachian

Power was a subsidiary of the Electric

Bond and Share Company, a major

utility holding company built up in the

form of a financial pyramid and

reported by the Federal Trade Commission

to have nearly $400,000,000

in watered stock. Essentially it was

contended by the Baker law firm in

the New River Case, on behalf of

Appalachian Power, that the Federal

Power Commission had no jurisdiction

over water power sites on navigable

streams located wholly within a state;

also that federal jurisdiction did not

include that part of a stream above the

point to which it was navigable.

"If the Power Trust, with Newton

Baker as its legal generalissimo, wins

the case," King argued, "it

means that federal jurisdiction as to the water

power over all the rivers of the United

States, navigable and non-navigable,

will be swept away and control of the

power sites thrown back to the states,

the most of which can easily be

controlled by the Power Trust."52

Franklin D. Roosevelt, on the other

hand, in King's judgment, particularly

after his speech at St. Paul on April

18, 1932, was "sound" on power and

"in line with progressive

principles," meaning that Roosevelt had come out

238 OHIO HISTORY

in support of effective regulation by

the federal government of the practices

and rates of the large utility

companies. King was pleased also by Roosevelt's

threat of federal intervention in the

power field unless corporations were

willing to accept a fair return on

capital, defined by the New York governor

as a "reasonable return on the

actual cash wisely and necessarily invested in

the property." This formula, known

as the prudent investment theory, as

opposed to the reproduction cost

formula, would eliminate profits based

on stock watering and inflation of

capital. Further, King reported ominously,

"Recent information from New York

and elsewhere makes it clear that

the banking and utility interests are

engineering a powerful movement to

control the next Democratic

Convention," presumably in behalf of Baker.53

Judson King's influence is not to be

minimized. Aside from his well known

association with George Norris, his

supporters in the fight against the

"Power Trust" included

Josephus Daniels, Felix Frankfurter, Morris Llewel-

lyn Cooke, and Edward Keating, editor of

Labor.54 At a meeting in Cooke's

home in Germantown, Pennsylvania, Cooke,

Frank Walsh (both members of

the New York State Power Commission),

and King decided to publish a

brochure comparing the power records of

the presidential candidates; the

intent of which was to convince the

public that the Power Trust was

seeking to dominate the nominees of both

parties. The pamphlet was

signed by fifteen Senators and some

ninety members of the House.55

If it was Judson King's conclusion that

"Baker has taken a long stray

to the right since I used to know him

back in 1906 to 1910 as the right

arm of Tom Johnson in Cleveland,"56

others, less radically progressive,

were more charitable. Thomas J. Walsh of

Montana came to the conclusion

that the Baker law firm's representation

of Appalachian Power "is to my

mind no legitimate basis for criticism

of Baker." Yet Walsh conceded that

in a political campaign this noted

lawyer would be charged "with being

attorney for the Power Trust. ... I am satisfied

that Roosevelt would be

the much stronger candidate, but not

because of any legitimate objection

to Baker on account of the power

[case]."57

Baker was well aware of the attacks

being made on him and his

vulnerability on the power issue. So as

not to appear to be an avowed

candidate, he confined his political

comments primarily to private correspond-

ence. In his letters he was candid in

his recognition of the distinction between

his own approach to power and that of

Roosevelt. For example, in a mem-

orandum to his law partner, Thomas

Sidlo, he pointed out that the record

would show that he had long ago, when

Secretary of War, recommended

government operation of Muscle Shoals

and "was always in sympathy with

the policy of the Federal Power Act

which makes possible short term leases

upon public power rights with a

recapture provision. Roosevelt is more

radical on this subject than I, as he

believes in public operation including

later distribution which is farther than

I would go unless it proved impos-

sible to secure fair and economical

distribution through private agencies."58

As for the New River situation, Baker

claimed that the Federal Power

Act was unconstitutional if an attempt

were made to apply it to non-navigable

BAKER ON THE FIFTH BALLOT? 239

streams located entirely within the

limits of a single state.59 And on the

Water Power Act itself, Baker claimed

that he had helped to secure its

passage. However, on what the public

power advocates considered the key

issue, distribution beyond the bus-bars,

"I do not think . . .," Baker wrote

Norman Hapgood, "that it would be

wise at the outset to carry Government's

operation beyond wholesale production,

leaving distribution in private hands,

under government regulation. This, I

think, is a less radical position than

Roosevelt has taken and doubtless is

less radical than Senator Norris'

position."60

Very nearly as important for his

candidacy as the question of public

power was Baker's stand on the

"open shop" issue. Professor Felix Frank-

furter of the Harvard Law School told

Stanley King, newly elected presi-

dent of Amherst College and a Baker

enthusiast, that it was not the

Clevelander's corporate relationship

with the power companies and the

Van Sweringen railroad empire but rather

his association with the open

shop policies of the Cleveland Chamber

of Commerce which prompted him

to prefer Roosevelt to Baker. And the

Roosevelt forces were determined,

if need be, to publicize the

Gompers-Baker correspondence on the subject.61

Samuel Gompers, president of the

American Federation of Labor, initiated

on August 19, 1922, what subsequently

became a published correspondence.

The labor leader expressed shock and

dismay that Baker in a pamphlet,

"The Human Side," as well as

in an advertisement in the Cleveland news-

papers, had been converted to the open

shop principle. This was not the

same Progressive, Gompers lectured, that

he had known during the war.

Baker, in reply, contended that a worker

should have the right to elect

not to join in a union and that the

Cleveland Chamber of Commerce, of

which he was then president, was not

anti-union. For Gompers this rejoinder

was merely a "pious cloak"

assumed by anti-union employers.62

Baker was bedeviled by other problems:

rumors of poor health (the heart

attack he had suffered in 1928 was now

common knowledge in political

circles); his membership on the

ill-starred Wickersham Commission;63 and

rumors of Hebraic ancestry, which he

deftly handled by claiming he was

not a Jew, but would be proud of his

ancestry if he were one.

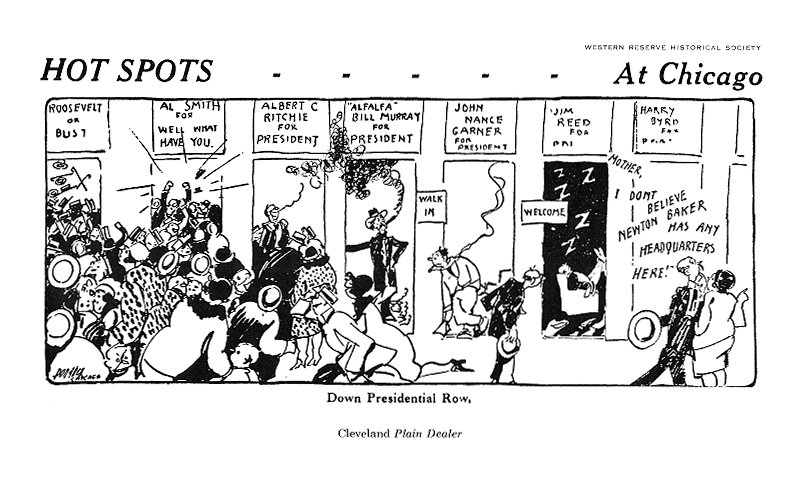

It is legend that the Democratic

convention at Chicago was so confused

and confusing a scene that claims as to

responsibility for the nomination

of Franklin D. Roosevelt are not likely

to be definitively settled. Claims

are legion on behalf of Farley, Garner,

Hearst, McAdoo, Mullen, Pittman,

and even Colonel House, who did not

personally attend the convention. The

tendency in the past, in the process of

attempting to resolve the question,

has been to miss the forest for the

trees.

In the vast array of incidents, deals,

and maneuvers, one development

seems to stand out as the turning point

in the selection of the Democratic

nominee in 1932 -- one who favored a

program such as the New Deal with

its domestic emphasis. That development

was William Gibbs McAdoo's

decision on the fourth ballot, prompted

by John Nance Garner and William

Randolph Hearst, to abandon the

stop-Roosevelt combination and to throw

240 OHIO HISTORY

the nomination of the governor of New

York. When the chips were down,

the stop-Roosevelt combination, put

together by Al Smith, Bernard Baruch,

and McAdoo with no common purpose except

to block Roosevelt and then

find an alternative candidate, collapsed

when it faced up to the possibility

that Newton D. Baker, the Wilsonian

internationalist, might become the

party's candidate. Smith and Baruch were

perfectly willing to accept

Baker's candidacy. But McAdoo and his principal

backers, Garner (Speaker

of the House of Representatives) and

Hearst (who headed a powerful

newspaper empire), for reasons we shall

examine, found Roosevelt more

ideologically acceptable than Baker.

The strategy of Ralph Hayes and the

Smith camp, presumably, had

attained its objective of preventing

Roosevelt from obtaining the necessary

two-thirds majority on the first three

ballots. As early as November 1931,

Hayes had written to Rabbi Stephen Wise

that Baker had declined to

accept open support or activity on his

behalf by "powerful elements in

the party" -- obviously the Smith

forces -- and would accept the nomination

only if tendered to him. "That

attitude," Hayes wisely concluded, had

"some disabilities" but also

"some advantages."64 He felt that if the Roose-

velt opposition, native sons, and

uninstructed delegations could command

the veto power of slightly more than

one-third of the convention, the con-

vention would eventually turn to the

Ohioan. An open candidacy by Baker,

on the other hand, could, very probably,

serve only to cancel himself out

as well as Roosevelt and leave the

nomination open for a third person. On

the eve of the Chicago convention the

strategy worked out by Hayes,

Shouse and their reluctant candidate,

Baker, seems to have worked for,

even though Smith was the avowed

candidate, Baker was now willing to

accept the nomination if it befell that

he should accept it as a personal duty.65

The final step in this strategy required

that the Smith forces get the

native-son and uninstructed delegations

to hold the line until the con-

vention reached a stalemate. No one in

the party wanted a repetition of

the deadlocked 1924 Democratic National

Convention; therefore, the check-

mating of Roosevelt would not require

very many ballots.66 The largest

bloc of non-Roosevelt votes, other than

those controlled by Smith was

the California-Texas bloc which

supported Garner and was controlled by

the Texan, Hearst, and McAdoo (of

California).

Accordingly, Al Smith, Bernard Baruch,

and William Gibbs McAdoo met

at the Blackstone Hotel in Chicago on

June 26, 1932, one day before the

convention assembled. The seeming

incongruity of a Smith-McAdoo meet-

ing, in view of their bitter contest for

the 1924 Democratic nomination (when

it was charged by Smith's followers that

McAdoo, with Klan support,

blocked his nomination) is explained by

the presence of Bernard Baruch.

Baruch was friendly with Smith and his

advisers and at the same time was

on good terms with McAdoo, since both

had been associated in the Wilson

administration with mobilization of the

home front for the war effort.

McAdoo's presence is also explained, perhaps,

by his financial indebtedness

to Baruch. Baruch, it was commonly

known, regarded Roosevelt unqualified

|

|

|

for the presidency ("a boy scout," was his description) and favored the nomination of Albert Ritchie, Governor of Maryland, Smith, or Baker. What transpired at that meeting and whether promises made were broken is dependent on whose word is to be accepted. Perhaps some examination of McAdoo's motivations, also a subject open to conjecture, is germane. On many occasions in 1931 and 1932 McAdoo made it clear that he opposed Roosevelt's nomination on several grounds: he was a New Yorker; he had done nothing about the graft and corruption of Tammany Hall; and he showed no great personal force. McAdoo desired the restoration of the West and South as the power base of the party.67 Related to this was the fact that McAdoo, quite possibly, entertained his own ambitions. He was frank in writing Colonel House in January 1931 that he opposed any New Yorker, including Roosevelt, as nominee and that Baker's failure to |

242 OHIO HISTORY

run for the Senate and his membership on

the Wickersham Commission

presented a formidable obstacle to his

candidacy. Moreover, Baker had no

large popular following. On the other

hand he, McAdoo, had had a strong

hold on the masses in 1924 which could

be revitalized.68 Other correspond-

ence later in 1931 and early in 1932

shows the Californian to be somewhat

more discreet, nevertheless open to a

draft: a draft that would have to

overcome opposing political forces, such

as the wet, the machine, and the

Wall Street elements.69 Aware,

therefore, of the unlikelihood of his own

nomination, except possibly in a

hopelessly deadlocked situation, McAdoo,

with the covert support of William

Randolph Hearst, waged a bitter primary

fight in California, his adopted state,

to secure its convention delegation

for House Speaker John N. Garner, who

fit McAdoo's qualifications for the

presidency. He had, in fact, put his own

prestige on the line by agreeing

in the spring of 1932 to head the Garner

slate in that state's presidential

primary in opposition to the Smith and

Roosevelt slates. And he had won

handily. Thus, McAdoo was clearly a

likely prospect for membership in

the stop-Roosevelt coalition at Chicago

-- but not necessarily in order to

lend support to Baker's candidacy.

According to McAdoo's recollection of

the luncheon with Smith and

Baruch on the eve of the convention,

Smith suggested that: (1) Roosevelt

could be stopped in a few ballots if

California and Texas stayed with Garner;

and (2) that when this point had been

reached, the various candidates

could get together and decide on an

alternative to Roosevelt. McAdoo

claimed later that he had refused to

enter such an agreement. In answer

to a query by Baruch, McAdoo had said

that he would be willing to give

notice before California changed its

vote to a candidate other than Garner,

only if such action proved feasible.70

There is also other evidence indicating

that McAdoo had, in fact, been

responsive to overtures from the Smith

camp even before he reached Chicago.

Thus Belle Moscowitz wrote an intimate

friend at Berkeley in June 1932

after the election of the McAdoo delegation

in California: "We have every

hope that the California situation will

turn out favorable to us and [there is]

every indication that it will be so."71

Furthermore, subsequent to the con-

vention Mrs. Moscowitz, Jouett Shouse,

Norman Hapgood, and other

Smith intimates claimed that McAdoo had

broken his pledge to hold his

forces until Roosevelt was stopped.

"If McAdoo had not broken the pledges

he made, Roosevelt would not have been

nominated," Shouse wrote Baker

shortly after the convention. If the

sizeable California delegation had not

shifted to Roosevelt on the fourth

ballot, Shouse believed, there would have

been defections from the Roosevelt ranks

"with the result that some other

nominee would have been certain. That

nominee would have been you

[Baker] or Ritchie."72

In his private correspondence, McAdoo

vehemently denied the charge

of a broken pledge, particularly after

an article on the subject by Frank

Kent appeared in the Baltimore Sun. But

Brice Clagett, McAdoo's son-in-law,

in a memo written during February 1933,

in a sentence crossed out, clearly

BAKER ON THE FIFTH BALLOT? 245

concedes that his father-in-law told a

Smith delegation just before the fate-

ful fourth ballot that he had decided to

abandon the stop-Roosevelt com-

bination.73 One can only

surmise from this and other evidence that McAdoo

had indeed been a member of the

coalition until some time between the

third and fourth ballots.

Between the end of the third and the

beginning of the fourth ballots it

became clear to many of those at the

convention that Roosevelt's chances

for the candidacy could not survive more

than one or two ballots.74 This

was not only the opinion of Jouett

Shouse and Ralph Hayes, but also of

such prominent party men as Paul V.

McNutt, Raymond Moley, John W.

Davis, Breckinridge Long and a host of

others, including Franklin D. Roose-

velt himself. Apparently Roosevelt was

not informed of the critical decision

-- who reached that decision, when and

where it was made is still a matter

of conjecture -- to give the Garner vote

of the Texas and California dele-

gations to the Roosevelt cause. It is a

matter of record that at 5:20 P.M.,

one hour before the fateful caucus of

the Texas and California delegations,

Roosevelt called Newton Baker in

Cleveland. He offered his support in the

event of a deadlock. "'It now looks

as though the Chicago Convention is

in a jam and that they will turn to

you,'" Roosevelt told Baker. "' I will do

anything I can to bring that about if

you want it.'"75

Even if one assumes that Roosevelt's

call was calculated to strengthen the

immediate prospects of his own

candidacy, the fact remains that he knew

enough of Baker's chances in one of the

subsequent ballots to take them

seriously. If he could not be his

party's presidential standardbearer, Roose-

velt evidently wished at least to be its

kingmaker.

It was William Allen White's conclusion

that Smith's failure to withdraw

after the third ballot led to the

Roosevelt nomination. "He could have given

Richey [sic] enough votes to

deadlock the Convention for a ballot or two

and then the South and West would have

led the parade to Baker . . ."

Only fear of another Smith nomination,

White held, kept the Roosevelt

delegations in line and made the

Hearst-McAdoo-Garner combination inevi-

table. "Smith certainly displayed

the talents of a provincial politician. . . . ."

There is no need here to decide whether

the key figure in the move to

checkmate Baker was Hearst or Garner

(who was consulting with Senators

Key Pittman and Henry B. Hawes and

Representative Edgar Howard).

It is sufficient to know that Hearst,

Garner, McAdoo, and a host of others

at the convention were keenly aware of a

shift in sentiment to Baker that

could quite possibly culminate in

Baker's nomination on the fifth or sixth

ballot. These people were especially

concerned because they held differing

political-economic views from Baker.

Hearst, Garner, and McAdoo were

economic nationalists, opposed

membership in the League, favored payment

of the debts by the European nations,

opposed United States entry into the

World Court, and had a powerful bias

against "the Wall Street interests,"

who were assumed to be Baker supporters.

It was on these grounds that

they decided to break the deadlock lest

Baker, or even Smith, emerge

triumphant.76

246 OHIO HISTORY

During the course of the critical fourth

ballot the Democratic party was

offered at the 1932 convention a choice

between Newton Baker's views and

those expounded by Roosevelt. Baker's

thinking, as indicated by his later

opposition to the New Deal, was more

attuned to that of Herbert Hoover

than to that of Roosevelt. The Ohioan

was at heart an internationalist and

also opposed to those

"advanced" Progressive concepts that became the

foundation stone of the New Deal.

Roosevelt, whose intellectual heritage

was similar to that of Baker -- both

were originally Grover Cleveland

Democrats -- was willing to go beyond

the simple reformism of the Pro-

gressive era. With a group of advisers,

principally three Columbia University

professors, Raymond Moley, Rexford

Tugwell and Adolf Berle, an approach

had been worked out to resolve the

enormous economic dilemma represented

by the Great Depression. That approach,

taken by Roosevelt, is best

described as intranationalism,77 the

essence of his campaign for the presi-

dency. As has been pointed out, it

placed priority on domestic recovery

and sought to prevent outside forces

from affecting that recovery. The

assumption was made that international

cooperation in economic matters

could only be achieved after each nation

had put its own house in order.

Accordingly the first New Deal, which

lasted through much of Roosevelt's

first administration, stressed domestic

remedies and reforms to the exclusion

of international considerations.

Thus, it can be said that Franklin D.

Roosevelt's economic nationalism

and progressivism in the end attracted

more support than Baker's economic

conservatism and cosmopolitan view of the

responsibility of the United States

in world affairs and so won him the

Democratic nomination in 1932.

THE AUTHOR: Elliot A. Rosen is As-

sociate Professor of History at Rutgers,

The State University. He has

collaborated

with Raymond Moley in the writing of

The First New Deal, published by Har-

court, Brace & World in December,

1966.