Ohio History Journal

Subsistence Homesteading

in Dayton, Ohio, 1933-1935

by Jacob H. Dorn

"The United States was born in the country and has moved to the

city,"

wrote Richard Hofstadter in a

provocative study of modern American re-

form movements.1 The tide of

migration from rural areas to urban centers

has been, with few exceptions,

continuous and irresistible since the begin-

ning of the Industrial Revolution.

Driven along by a host of economic,

social, and psychological forces, it

reached a symbolic watershed in the

1920's, when for the first time the

majority of Americans lived in urban

areas. City dwellers, however, have

often maintained a wistful longing

for restoration of the simpler,

individualistic values of a rural past and

even organized movements to reshape

American society through back-to-the-

land experiments. The belief that rural

life--with its idealized contact with

the soil, virtuous self-reliance, and

basic economic security--is superior to

urban conditions has never lacked

spokesmen, many of them consciously

indebted to Jeffersonian precepts.

Periods of urban-industrial crisis, more-

over, have been especially conducive to

nostalgic--and sometimes reac-

tionary--revulsion against the city.2

The Great Depression that followed

the stock market crash of October 1929

was one such crisis, which suddenly

and unexpectedly quickened the hopes of

faithful disciples of rural life.

The intellectual foundation for the

back-to-the-land movement of the

1930's was laid by a variety of

individuals and groups who had developed

in the previous decade a full-blown

agrarian philosophy. It may seem sur-

prising that these agrarian

theoreticians turned to a rural panacea during

the 1920's, when acute agricultural

depression stood in sharp contrast to

urban prosperity, but these would-be

reformers retained a romanticized

vision of life on the land and, in fact,

blamed urban-industrial centraliza-

tion for rural America's problems.

Whether designating themselves New

Humanists, Distributists, or something

else, they shared a common concern

for the preservation of a rural life

that was threatened by urbanization

and industrialization, the forces they

considered to be the causes of ma-

terialism, waste, ugliness, and

dehumanization in American life. A unified

cry was heard in the twenties for a

return to decentralized social and

economic activities.3 The

onslaught of depression enhanced this appeal

NOTES ON PAGE 146

76 OHIO HISTORY

and stimulated a popular burst of

back-to-the-land sentiment among un-

employed city-dwellers and among public

figures as diverse as Henry

Ford and Franklin D. Roosevelt.4 Many

of those who participated in or

endorsed the movement, however, did so

for reasons of personal economic

survival or security or because of

considerations of public policy (e. g., the

pressing need to counteract lengthening

relief rolls), and not because

they shared fully the agrarian

philosophers' antipathy to urbanization

and industrialization.

The back-to-the-land movement of the 1930's

eventually enlisted the

support of a variety of public and

private agencies and groups. At first,

voluntary associations, sometimes with

the support of public agencies,

experimented with relocation of the

impoverished and with community-

development programs as long-range

solutions to the problems of un-

employment and relief. For example,

beginning in 1931 at the request of

President Hoover's Commission on

Unemployment Relief and of the

Federal Children's Bureau, the American

Friends Service Committee under

Clarence E. Pickett, its executive

secretary, began an extensive program of

relief among depressed miners in the

bituminous coal fields of the Ohio

River Valley. Assisted by the Federal

Council of Churches, the United

States Bureau of Education, and the

Pennsylvania State Bureau of Educa-

tion, the committee began moving miners

to subsistence farms located

elsewhere. For those who remained in the

mining towns, a program was

launched that combined part-time farming

with part-time mining.5 Even-

tually, in response to the varied

spontaneous efforts of such private groups

and to sympathetic voices within the

Roosevelt administration, the Federal

Government became directly involved in

this type of aid through a pot-

pourri of programs including subsistence

homesteading, resettlement and

improved land use, and the creation of

garden cities or "greenbelt" towns.

One back-to-the-land effort that

reflected the rural-life sentiments of

the 1930's and whose origin preceded New

Deal intervention was the

organization early in 1933 of a

subsistence-homestead community near

Dayton, Ohio. The brief life of this

community has significance for the

social history of the 1930's for several

reasons. First, the Dayton project

aroused widespread interest as a

potential laboratory for homesteading

nationally, since it was the first

subsistence-homestead unit under local

sponsorship to receive Federal support

once the New Deal included this

type of aid in its programs. Sometimes

the possibility that it might become

such a laboratory led to expansive and

unrealistic hopes among its pro-

moters and members. Second, the internal

tensions that contributed to

its eventual collapse illustrate the

dissimilar motivations and goals that

existed in this and other

back-to-the-land experiments. In Dayton at

least three separate and distinct

perspectives on homesteading manifested

themselves in the administration of the

community: one, that of the social

planners who held a predetermined

philosophy of homesteading that was

not easily adapted to pragmatic

situations; two, the viewpoint of com-

munity leaders, many of whom valued

homesteading in relationship to

SUBSISTENCE HOMESTEADING 77

unemployment and relief rolls and not as

an ultimate direction for societal

evolution; and, three, the approach of

some homesteaders themselves, who

refused to sacrifice self-interest and

immediate security to the visionary

demands of community solidarity and

social reconstruction. And finally,

the experiment of the Dayton community

provides insights into the inter-

play of interests and pressures between

Federal agencies and local proj-

ects during the early years of the New

Deal.

The impetus to subsistence homesteading

in Dayton came from an

attempt in the summer of 1932 to deal

with unemployment by organizing

within the city a network of cooperative

production units. In these units

unemployed workers produced food,

clothing, shoes, and other essential

commodities for their own use and for

barter. Leadership and support

for these units, which were organized

into the Dayton Association of

Cooperative Production Units, came from

the Bureau of Community Serv-

ice, a coordinating agency and

clearing-house for the city's specialized

philanthropic and welfare agencies. This

bureau, an outgrowth of the

"scientific-charity" movement

of the late-nineteenth century, carried on

no direct social work itself; instead,

it functioned as a planning and fund-

raising body through two departments,

the Council of Social Agencies

and the Community Chest.6 Finding

both private and public welfare

inadequate in the face of massive

unemployment, the Council of Social

Agencies, led by the director of its

division of character building, Elizabeth

Nutting, organized the production-unit

movement in order to make the

unemployed more self-sufficient and also

to reduce demands on relief

agencies.7

Altogether about twelve production

units, involving between 350 and

500 families, were organized. In

addition to barter among themselves, they

had an arrangement with Dayton's welfare

director, Edward V. Stoecklein,

to exchange their products (which the

city distributed to relief recipients)

for raw materials. Late in 1933 the

Federal Civil Works Administration

began to integrate the units into its

own operations, but the production

units had by then reached a plateau of

effectiveness.8 Apparently, a feel-

ing early in 1933 that production units

within the city were not an

adequate solution to the problems of

relief led members of the Council

of Social Agencies' production-unit

committee to think in terms of land

colonization or homestaeding. At least

one member of this committee,

Elizabeth Nutting, admired the writings

of Ralph Borsodi of Suffern, New

York, and at her urging he was brought

to Dayton three separate times

in January 1933 to explain a plan of

subsistence homesteading, whose work-

ability he had demonstrated during the

1920's at Suffern.9

One of the most influential proponents

of economic decentralization,

Borsodi was, in the judgment of the

historian of the New Deal community

programs, "the supreme exemplar of

self-sufficient farming and successful

back-to-the-land" experimentation.10

Borsodi's ideas have received careful

analysis elsewhere,11 and it is

necessary here only to underscore a few of

his major ideas. He wrote numerous books

and articles, both before and

|

78 OHIO HISTORY after his participation in the Dayton community. These included The New Accounting (1922), a work on double-entry bookkeeping, National Adver- tising versus Prosperity (1923), an analysis and comparison of the costs of his "domestic production" at Suffern with large-scale manufacturing, The Distribution Age (1927), in which he argued that producers suffered lower income while consumers paid higher prices because of the exorbitant costs of distribution and transportation, advertising, and selling required by centralized production, and Education and Living (1948), an expanded statement of his social philosophy. But the book that, by his own account and by the testimony of spokes- men in Dayton, brought him and the movement in Dayton together was This Ugly Civilization. First published in 1929, when it aroused relatively little attention, the book was reissued in 1933, when depression conditions made it more popular.12 In this work, the city-bred Borsodi revealed a profound anti-urban bias. The "ugly civilization" of "noise, smoke, smells, and crowds-of people content to live amidst the throbbing of its ma- chines," was uniquely ugly because for the first time society had the ma- chines to make life beautiful; yet, instead of using those machines to release its citizens' energies for creative living, it used them "mainly to produce factories-factories which only the more surely hinder quality-minded individuals in their warfare upon ugliness, discomfort, and misunderstand- ing." There was nothing wrong with machines as such, he argued; the mistake consisted of transferring machines to the factories and thereby destroying home production and the small workshop. The desire for ef- ficiency was the basic motive for production in a factory, but along with efficiency this method of production imposed an "institutional burden" on the economy in the form of transportation costs, general administra- tive expenses, and the demand for profits. Domestic production, Borsodi's alternative, was free from the relentless pressures for efficiency and con- tained no counterparts to the "institutional burden" of factory pro- duction.13 In addition to the disadvantages imposed on society as a whole, factory |

SUBSISTENCE HOMESTEADING 79

production resulted in a wide

discrepancy between what the producer

or worker received and what the consumer

had to pay. Individual, family,

and social fulfillment were also

obstructed. Among other affects on the

person, the factory reduced workmen to

"mere cogs in a gigantic industrial

machine," decreased the number of

those who engaged in truly productive

and creative labor, arrayed workers against

employers, weakened the posi-

tion of self-reliant, skilled craftsmen,

and undermined individualism and

self-esteem. The techniques and spirit

of factory production had even in-

vaded the countryside, and farmers were

turning to cash crops that left them

dependent upon outside sources for

essential commodities. According to

Borsodi, the way out of this "ugly

civilization" should be led by small groups

of "quality-minded"

individuals who would organize their families into self-

suffcient units through the use of

labor-saving machines within the home.

This elite, he warned, should not expect

the urban masses to adopt home-

steading unless a national economic

catastrophe struck, but such an elite

could at least find a richer existence

for itself.14 His proposed homesteads

were essentially an escape, idyllic

little pockets of "intelligence and beauty

amidst the chaotic seas of human

stupidity and ugliness."15

Following Borsodi's informal visits to

Dayton in January 1933, suf-

ficient interest in subsistence

homesteading had developed for the Council

of Social Agencies to set up a Unit

Committee separate from its committee

on production units. The Unit Committee,

whose first chairman was the

Reverend Charles Lyon Seasholes of the

First Baptist Church, consisted of

prominent civic figures: General George

H. Wood, head of the Veterans'

Administration's facility in Dayton, and

his wife, Virginia P. Wood, a mem-

ber of the Oakwood school board; Arch

Mandel, executive secretary of the

Bureau of Community Service; Robert G.

Corwin, an attorney; Sam H.

Thal, the owner of a downtown department

store; Edward V. Stoecklein,

Dayton's Director of Public Welfare;

William A. Chryst, a consulting

engineer for Delco Products Company; and

several other professional and

business men. This Unit Committee began

in February 1933 to solicit

community support for a homestead

project and to secure suitable land

at a reasonable price.16 Borsodi

continued to make special trips to Dayton

to a d v i s e the committee and to

address public meetings, and by May

he had joined the project as official

adviser.17

After appraising several available

properties, in mid-April the committee

purchased the farm of Dr. Walter Shaw, a

160-acre tract four miles west

of Dayton on the Dayton-Liberty Road,

one-half mile south of Route 35.

This farm, for which the committee paid

$8,050 on a fifteen-year contract,

contained a substantial brick home and

several out-buildings that could

be used as temporary quarters, and was

intersected by Bear Creek, which

seemed to hold both aesthetic and

functional advantages for the project.

The original plan was to divide the farm

into thirty-five three-acre tracts

for as many families, and to use the

remainder of the acreage for common

parks, roads, pasture and tilled fields,

orchards, and woodlands. At

Borsodi's suggestion, the Unit Committee

made plans to finance the entire

80 OHIO HISTORY

enterprise through the sale of

"Independence Bonds" worth a total of

$35,000. These bonds, issued in

denominations of $50, $100, and $500

would bear interest to their purchasers

of 41/2 percent for periods up

to fifteen years. Estimates of how much

it would cost to provide each

homesteader with a house and supplies

varied from $750 to $1,000, but

it was apparently with the lowest figure

in mind that the committee

decided on a bond issue of $35,000. The total cost of

$26,250 for thirty-

five families at $750 per family, added

to the cost of the farm, $8,050,

would only slightly exceed $35,000.18

The homestead community was officially

launched on Sunday, May 14,

1933, at a public dedication at which

the principal leaders of the project,

Borsodi, Elizabeth Nutting, Sam H. Thal,

and Robert G. Corwin, made

optimistic predictions. Borsodi noted

that more than economic security

was at stake: "Two hundred years

ago at the time of the industrial revolu-

tion, when machines moved out of homes

into factories, we lost the key

to living. I believe the way is planned

here to return the key."19

In the week following this dedication,

several homesteaders moved into

the brick farmhouse that was to serve as

temporary lodging until construc-

tion of individual houses could begin in

the summer. Kenneth Butler, a

local architect, joined the unit as

building adviser, and Leslie M. Abbe,

an engineer from Indianapolis who had

come to Dayton with his family

after hearing of Borsodi's work, assumed

the task of first-hand supervision

on the site. The homesteaders were to

build their own "rammed-earth"

houses, financed by loans from the Unit

Committee. The promoters hoped

to secure cooperation from local

industries, which would supply part-time

work to provide a living for the

homesteaders until they could become

self-sufficient, and from unions in the

building trades, which would teach

the homesteaders essential contruction

skills.20

Whatever Borsodi's long-range dreams, it

became clear in the weeks

following the dedication that other

community leaders predicated their

support on differing and sometimes

conflicting goals. Some supporters

were primarily interested in providing

housing for local families with

reduced income to enable them to live

and work near the city, the develop-

ment of an atmosphere of confidence that

might stimulate economic re-

covery, or the reduction of the city's burdens

of relief and dependency.

The Dayton Daily News, whose

editor, Walter Locke, served on the Unit

Committee, seemed to sense Borsodi's

social ideas more than many other

local supporters. In an editorial on

June 9, 1933, this paper hinted at

the potential significance of

homesteading:

The people who are all farmer have been

for more than 10 years

in a direful state. Tied to the land,

the land unable to return them a

living, they have suffered in

helplessness. Now for four years the

people who are all-city have been in

direful straits. Dependent wholly

upon jobs, they have lost their jobs.

Their jobs lost, all was lost ....

But there is another estate, the

independent farmer-laborer, which has

not yet been much thought of or much

developed.

And in July, another editorial predicted

that

SUBSISTENCE HOMESTEADING 81

This unit may be the laboratory out of

which will come a serum

that will forever lay the spectre of

grim want that has haunted millions

of families for the past four years and

further immunize many against

the virus of technological

unemployment.21

As Locke saw it, homesteaders would have

a foothold in both the industrial

and agricultural worlds and would be

victimized by neither. Urban jobs

would supplement subsistence farming

during times of general prosperity,

while homestead plots would provide

basic security during hard times.

The construction of houses and

organization of the homestead unit

began in a great wave of optimism in the

summer of 1933. Groundbreak-

ing for the first house occurred on June

11, plans were laid to begin work

on four additional dwellings, and a

rudimentary system of committees and

officers began to function by late June.

John Arbuckle, a graduate of the

Ohio State University's School of

Engineering, became manager of the

unit, and Paul Cromer, a former high

school teacher who had been active

in the production units, was elected

president of the community.22 Ap-

parently, homesteading appealed

primarily to middle-class people--Borsodi's

elite--rather than to the neediest

members of society for the first group

of homesteaders accepted by the Unit

Committee included two civi1

engineers, two agricultural experts, two

electricians, a plumber, a mechanical

engineer, a chemical engineer, a

librarian, three nurses, several teachers,

and an architect.23

From time to time, Borsodi and Elizabeth

Nutting issued promising

statements about the progress of the

unit, but practical results remained

elusive. Although about thirty

applications received approval and a dozen

or so families began planting small

gardens on their three-acre plots, not

one house was near completion by the end

of the summer. The home-

steaders found that rammed-earth

construction, even though inexpensive,

required too much labor and had to be

given up in favor of cinder blocks.

The few families that had moved onto the

Shaw Farm lived in tents,

makeshift huts, sheds, the brick

farmhouse, and, in one case, a grass shack,

while the others commuted from the city

to tend their gardens. Early

in September the homesteaders' hopes

received a jolt when fire destroyed

a log structure on the farm resulting in

a loss of $5,000 to the building

and household goods. The building had

been insured, but the household

goods had not, and several homesteaders

suffered a serious setback.24 An-

other financial burden was added when

the promoters revised their

estimates of the cost per family upward

from $750 to $1,071 very early in

the summer.25 Also, by the

end of the summer internal tensions had

become apparent. In Miss Nutting's

report to the Unit Committee she

stated, "a weak manager and a

strong personality in the group exerting a

negative influence, have combined [with

other factors] to undermine

morale and reduce efficiency."

Discord and bickering almost from the first

had obstructed physical progress on the

unit.26

Despite obstacles, Borsodi's plans for

homesteading in Dayton grew more

grandiose. Although contruction moved

with painful slowness and no as-

82 OHIO HISTORY

sistance from local builders or trade

unions was forthcoming, he began

to think in terms of building a ring of

fifty homestead communities around

Dayton to accommodate no less than 1,750

families. Since financing of

even one unit seemed impossible locally,

as the failure of the "Independence

Bonds" drive made plain, it was

clearly necessary to turn to the Federal

Government for assistance. With such an

appeal in mind, Borsodi tried

again to enlist the enthusiasm of civic

leaders as evidence of the viability

of his plans. He asked Arthur Morgan,

who had left nearby Antioch College

in Yellow Springs to become director of

the Tennessee Valley Authority,

to use his personal influence in the

Roosevelt administration. Responding

to Borsodi's urgings, on May 22 the Unit

Committee also voted to seek

$2.5 million from the Reconstruction

Finance Corporation under the sec-

tion of the Emergency Relief and

Construction Act of 1932 providing funds

for self-help and barter associations.

Borsodi visited Washington and tried

to work through both Morgan and

Representative Byron Harlan of Dayton.

In connection with the request for Federal

aid, an advisory board of

eminent educators, consisting of Harold

Rugg, Clarke F. Ansley, and Wil-

liam H. Kilpatrick of Columbia

University, Boyd H. Bode of the Ohio

State University, Eduard C. Lindeman of

the New York School of Social

Work, Harry A. Overstreet of the College

of the City of New York, and

Arthur Morgan, agreed to oversee the

cultural and adult-education pro-

grams of the proposed fifty units.

During June and early July the promoters

in Dayton were buoyant in

anticipation of the creation of the

prime laboratory for homesteading in

the nation. On July 13, however, the

newspapers reported that Arch

Mandel of the Bureau of Community

Service had received notification

that there would be no loan from the

RFC. The reasons for this refusal

are unclear, but two factors may have

had some bearing. First, there was

some feeling that Morgan's support of

the project was less than enthus-

iastic, partly because he doubted the

ability of the existing Unit Committee

to administer so much money. Second,

there was overt opposition from

the Dayton Property Owners' Association,

which sent letters to Washington

opposing the grant on the grounds that

it would disturb local building

conditions and also possibly handicap

applications from Dayton for other

types of Federal aid.27

Just as Borsodi's hopes for a loan from

the RFC were fading, a new

potential source of Federal support

emerged, when Congress passed the

National Industrial Recovery Act on June

16, 1933. Section 208 of Title

II of this act provided $25 million for

the President to use for subsistence

homesteading, and Roosevelt chose to

administer this allocation through

a new Division of Subsistence Homesteads

created in the Department of

the Interior. To run this new agency,

Secretary Harold L. Ickes selected

an agricultural expert, Milburn L.

Wilson, who had pioneered in agricul-

tural-extension work in Montana. Wilson

was sympathetic with the idea

of subsistence homesteading, partly

because of his first-hand observation

of the self-contained Mormon villages in

Utah, and his own attitude was

|

SUBSISTENCE HOMESTEADING 83 close to Borsodi's emphasis on decentralization of industry and local control of administration. Borsodi, who took full credit for eventually securing a loan from the Division of Subsistence Homesteads, later observed: "Of all the men in places in power with whom I dealt, Dr. Wilson alone understood what I meant when I said that the Dayton homestead plan was different-that it was essentially educational in nature."28 Favorably disposed toward the project in Dayton, Wilson inspected the unit on September 1, 1933, and, although a formal loan grant was not drawn up until September 29, participants in Dayton felt assured within a few days after his visit that a loan of $50,000 would be forthcoming. The Dayton unit was the first, out of an estimated five hundred applicants, to receive funds from the division. This distinction should not be considered unusual, however, for this unit was already under construction. It had originated almost entirely through local initiative and had continued to enjoy broad support in the community. It also had the considerable asset of direct association with Borsodi's reputation as a homesteading expert, and it had the backing of important politicians in Ohio, including Governor George White.29 Early in October 1933, Borsodi brought from Washington a check for $9,000 to pay for the Shaw Farm, which the Unit Committee had until then held under option. Still thinking of ultimately dotting the circumfer- |

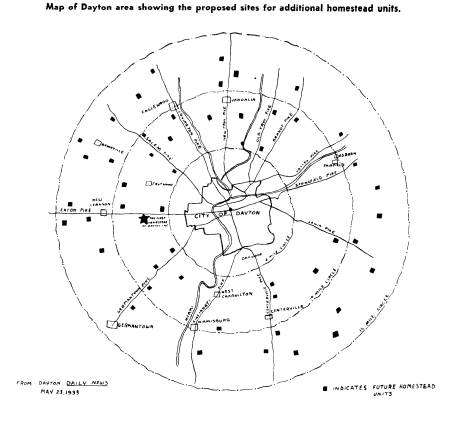

84 OHIO HISTORY

ence of Dayton with homestead units, he

forecast a favorable Federal

response to another request for $2.5

million for fifty units.30 This expan-

sive optimism, continuing through the

winter of 1933-1934, accounts for

the project leaders' distraction by

ventures that were at best peripheral

to the needs of the few struggling

homesteaders already on the Shaw Farm.

The first distraction was a national

homesteading conference held in

Dayton on December 7-9, 1933, organized

to focus attention on Dayton

as a spearhead of the back-to-the-land

movement. According to Borsodi

and Miss Nutting, social workers, civic

leaders, and educators elsewhere

were simply yearning to see what was

going on under their leadership on

the Dayton-Liberty Road farm.

Apparently, they were not at all chagrined

by the fact that the first two houses

were still incomplete when the confer-

ence opened. Featuring addresses on

various aspects of homesteading

(Hughina McKay, a professor of home

economics at the Ohio State Univer-

sity, discussed the relative advantages

of cow and goat milk and came out

emphatically for goat milk) and tours of

the Shaw farm, the conference

was not a total disappointment; but it

did not meet the grandiose expecta-

tions raised by Borsodi's and Nutting's

publicity. Invited guests, such as

Milburn Wilson, Arthur Morgan, and

Bernarr Macfadden, another popu-

larizer of homesteading, were unable to

come at the last minute. The highest

ranking Federal officials in attendance

were Frank Fritts, general counsel of

the Division of Subsistence Homesteads,

and Clarence E. Pickett, a sec-

tion chief in the division. President

George W. Rightmire of the Ohio

State University served as chairman, and

the majority of the speakers were

professors from Columbus whom Borsodi

had enlisted as advisers and

instructors for the unit.31

Much of the discussion reflected the

nostalgia that characterized the

diverse elements in the back-to-the-land

movement. The Reverend Charles

Wesley Brashares of Dayton's Grace

Methodist Church, later a bishop of

his denomination, addressed one meeting

with these words:

The city presents the unsolved problems

of self-government; the

village governs itself. The city suffers

extreme wealth and extreme

poverty; the village is democratic. The

city renders multitudes un-

employed; on the land about the village

there is always work to be

done.32

The conference also elicited expressions

of interest in homesteading from

two large industries in Dayton--for

quite different reasons. Both the

National Cash Register Company and the

Delco Products Company, con-

cerned about the possibility of

legislation shortening the workweek indi-

cated willingness to undertake homestead

units exclusively for their em-

ployees to use in supplementing reduced

incomes. Their motives seemed

to be somewhat similar to those behind

traditional company towns.33

A second distraction from the work on

the immediate needs of the first

homestead was Borsodi's growing

preoccupation with securing loans for

additional units. This preoccupation was

in part a response to the desire

of people in the production units to

move into subsistence homesteading.

SUBSISTENCE HOMESTEADING 85

Their interest in homesteading grew out

of their need for food and raw

materials and their deepening conviction

that production units were at

best makeshifts. As early as April 1933,

the East Dayton production unit

had purchased a farm on which several

participating families would live

and raise produce for the majority of

the members, who stayed in the

city to carry on the unit's small-scale

manufactures.34 Borsodi saw in this

development the beginnings of a

potentially great demand for subsistence

farms and an opportunity to project his

plans on a massive scale. More-

over, according to his c1aims, the

Division of Subsistence Homesteads

favored the conversion of urban

production units into homestead units.

By March 1934, Borsodi had made plans

for four additional homestead

units, which were to accommodate about

two hundred families, as a first

step toward his goal of fifty. The first

additional unit, sponsored by the

North Dayton and Stillwater production

units, was to be located on the

162-acre farm of T. P. Whitmore

northeast of Dayton on Brandt Pike and

was to be called Willow Brook. The second

and third additional units,

Rolling Acres and Miami Homesteads, were

to be located on adjoining

farms bounded by Wagoner Ford Road,

Needmore Road, and the Miami

River, north of Dayton. The fourth new

unit, Valley View, to be composed

of Negro homesteaders, was projected for

the farm of E. L. and Ira Risner on

Carrollton Road, west of Dayton. On

behalf of the Unit Committee, Borsodi

placed a loan application for $309,400

for these units with the Division of

Subsistence Homesteads, and on March 3,

1934, the division's board of di-

rectors approved the request. In this

same expansionist mood, Borsodi sug-

gested that Congress should appropriate

about one billion dollars for the

Division of Subsistence Homesteads in

1934.35 The projection of new units

for Dayton not only diverted energies

from the first unit, but also became a

source of conflict between the local

movement and the Federal subsistence-

homestead program.

Just as Borsodi's efforts in Washington

seemed guaranteed of success,

a cluster of troubles began the undoing

of the homesteaders' dreams. The

first serious issue was the organized

protest of hundreds of residents of

Jefferson, Madison, and Harrison

townships, where the new units were

to be established. The center of protest

was Jefferson Township, where

planners hoped to locate Valley View,

the Negro unit. On March 27, 1934,

an indignation meeting of several

hundred property owners raised objec-

tions on the ground that the new units

would increase taxes, overcrowd

the schools, and, somewhat

contradictorily, bring in both "upper crust"

people and nudists. Spokesmen for the

homesteads successfully refuted the

argument about taxation by pointing out

that, although homesteaders

would technically not hold title to

their land (they would hold modified

single-tax leases from a unit

corporation), they would make prorated pay-

ments to the unit, which would in turn

pay its fair tax assessment. The

protesters continued to argue about taxation

and overcrowded schools, and

through their spokesmen, Bryan Cooper,

an attorney, they lodged com-

plaints with Senator Robert J. Bulkley

and Representative Byron Harlan.

86 OHIO HISTORY

At least for the residents of Jefferson

Township, the key issue seems

to have been race. In response to a

request for clarification of a petition

signed by over 1100 protesters, Cooper

and two other leaders of the agita-

tion submitted to the Division of

Subsistence Homesteads through Borsodi

a document preponderantly devoted to

objections to a Negro unit. This

document referred to the disastrous effects

on schools, property values, and

racial purity that would supposedly

result from the "arbitrary implanting

of a colony of thirty-five or more

families of colored people with their

lower standards of living" in the

midst of white people who maintained

by "inheritance and culture the

higher standards of living." It called on

the Division of Subsistence Homesteads

to allow white communities to

"pursue their development without

blending with the Ethiopian race,"

suggested placing the Negro unit next to

existing Negro areas on the West

Side of Dayton, and threatened an appeal

to the courts and "if necessary

to the court of last resort for

protection."36 Partly because of this protest,

but largely for other reasons, Secretary

of the Interior Harold L. Ickes

early in May sent a member of the

division's staff, W. E. Zeuch, to

investigate the situation in Dayton.

Ickes was not one to bend to racial

prejudice, and the protest from

Jefferson Township did not influence his

subsequent decisions with respect to the

projected units.37

A much more serious issue for the future

of homesteading in Dayton

was the eruption of sharp internal

criticism of Borsodi's management in

the unit itself, criticism taken up and

turned into a sustained attack by

the Dayton Review, a weekly civic

newspaper. Because of scanty records,

it is impossible to construct a complete

narrative of the controversies, but

it is possible to indicate the nature of

the issues. The first signs of dissen-

sion appeared in the autumn of 1933 and

emanated from a young member

of the homestead, Miss Charlotte Mary

Conover.38 In an open letter to

Borsodi on November 15 Miss Conover

complained of delays in the con-

struction of her home (and favoritism to

Elizabeth Nutting in the build-

ing of hers), constant changes in the

rules and constitution of the unit,

and building costs substantially higher

than Borsodi's original estimates;

she also accused Borsodi of being an

interloper and questioned the source

of his salary. Miss Conover transmitted

her criticisms to the Unit Com-

mittee, and eventually to Clarence

Pickett of the Federal Division of

Subsistence Homesteads. Borsodi reacted

by having Miss Nutting send a

letter of refutation to every member of

the Unit Committee and by speed-

ing up work on Miss Conover's house.39

As for Borsodi's salary, it appears

that he received at first about $200 per

month from private contributions

of members of the Unit Committee and an

expense account from a budget

of $1,000 allocated to the units by the

Dayton Community Chest; there

is also evidence that he received some

funds from the loan of $50,000 from

the Division of Subsistence Homesteads.40

After prolonged controversy

through much of 1934 and the threat of

litigation, the committee decided

to compensate Miss Conover for her

actual investment in her home, which

by April 5, 1934, represented a total investment of

$2,054.63, in return

for her relinquishing all claims in the

homestead unit.41

SUBSISTENCE HOMESTEADING 87

The case of Miss Conover was just a

ripple before the tidal wave of

criticism that rolled in during April

and May, 1934. Beginning on April

6 and continuing almost weekly into

June, the Dayton Review seized on

every bit of discontent available.

Asking in front-page headlines, "What

Is the Truth About the Homestead

Units?" this paper charged that

Borsodi and Nutting were "running

wild" now that Federal money seemed

in the offing, that they were

"mysterious figures in Dayton" whose sources

of income should be investigated, that

the public knew "woefully little

about the project," and that

support of homesteading was beyond the

proper scope of the Community Chest.42

On April 20 the Review gave

its fullest coverage to the problems of

the unit, including a front-page

rehearsal of earlier grievances and a

prediction of wholesale resignations

of members of the Unit Committee in

protest against "czar" Borsodi's

"dictatorial usurpation of

authority." The Review's specific targets included:

Borsodi's alleged attempt to make the

Unit Committee a mere rubber-

stamp by reducing its membership from

fifteen to five; Borsodi's and Miss

Nutting's evident desire to expel Miss

Conover, the only homesteader who

had so far questioned their management;

and the victimization of the

homesteaders on the Shaw Farm. After an

entire year of activity on this

unit, the paper claimed, only eight

families were on the land, and only

one occupied its own permanent house.43

The Review on April 20 also

printed, in adjacent columns, two different

replies to the questions it had raised

on April 6. In a spirited defense of

the unit and its management, Elizabeth

Nutting, as one respondent,

quoted extensively from its constitution

to demonstrate the broad social

purposes of homesteading and from the

lease agreement made with each

homesteader. The entire system of land

tenure, she explained, equitably

balanced the interests of the

homesteader with those of the entire unit.

In order to prevent speculation in land

and houses and to preserve economic

and aesthetic unity, land tenure in fee

simple had been rejected in favor

of corporate ownership.44 Each

homesteader received a lease for his plot

and paid an annual "ground

rent," which included principal and interest

of 5 1/2 percent on his loan from the

Unit Committee, the tax assessment

on his land and any property on it, and

a share of communal and admin-

istrative expenses. This rental payment

was fixed by a nine-member board

of trustees, elected from the membership

of the homestead community,

there was a system of arbitration to

settle challenges to the trustees' decisions,

and there was provision for voluntary

withdrawal on sixty-days' notice

and for eviction by a vote of two-thirds

of the members. Miss Nutting

also defended the process of accepting

applicants for the homesteading

project and rejected charges that

Borsodi had received any salary from

the Community Chest.

The other reply from an

"unidentified homesteader," perhaps Miss

Conover, marshaled much of the same data

summarized by Miss Nutting,

but differed sharply with her about the

justice and equity of the project.

For example, this respondent claimed

that the selection of homesteaders

88 OHIO HISTORY

had been very arbitrary and that

agreements made with them were easily

broken. For the first nine months, two

young women in Miss Nutting's

"household"--religious-education

workers who followed her from job to

job--had investigated applicants with an

eye to providing the community

with varied skills, but their judgments

of skill had been untrained and

overly optimistic.45 In

January 1934, when the Unit Committee finally

adopted a uniform questionnaire to be

used in processing applications,

the questions had been highly personal

and subjective.46 Moreover, this

critic contended, even after

homesteaders had gone through the tedious

process of admission, they were not

secure from being "later forced quietly

out of the unit on one pretext or

another." On the matter of land tenure,

the procedures outlined by Miss Nutting

were only theoretically operative;

in practice, Borsodi had a "habit

of bland disregard for all agreements

and understandings, if he feels inclined

to disregard them." Plans for

housing construction had repeatedly

changed, to the detriment of the

homesteaders and of architectural

homogeneity. Convenience and sanita-

tion were proving elusive, as the

planners failed to fulfill promises for

inside plumbing, leaving homesteaders to

face the prospect of outhouses

and, at times, backyard holes for sewage

disposal. Also, the community

officers were charged with

discrimination in construction and in the use

of communal tools and facilities; they

and their friends had preferential

treatment in getting land plowed and

houses begun.47

In subsequent issues the Review, receiving

its information from dis-

gruntled homesteaders, focused on

Borsodi as the cause of all the unit's

troubles. He was accused of being an

interloper, posing as an experienced

homesteader. The Review claimed

that his home in Suffern was three

and one-half stories high and contained

a billiard room and that his

pious talk about comfort and security

must have a hollow ring to people

living in huts and shacks. Essentially

the same point was made in a

review of his book Flight From the

City for the Nation. The reviewer

concluded that Borsodi's broad social

application of his own special

experience, based on regular, reliable

outside income, made his book "an

exceedingly dangerous and even a

dishonest piece of propaganda."48

A related argument by the Review was

that Borsodi exaggerated his

achievements in Dayton, evidently in the

interests of his own national repu-

tation. The paper cited some publicity

for Flight From the City that pro-

claimed, "hundreds of families have

been placed on self-sufficing home-

steads according to his methods" in

Dayton. The facts were that only a

handful of persons had taken up

residence on the unit. Whether or not

Borsodi was culpable, some

misrepresentation did creep into reports on

the unit. One article in a national

magazine included pictures of four

"typical" houses--all

substantial structures, two of stone, one frame, and

one concrete or stucco. Another article

by Borsodi included pictures of

a room full of looms and a large

building for small-scale manufactures,

both of which were probably facilities

operated by production units but

certainly not by the

subsistence-homestead unit.49 Still another criticism

SUBSISTENCE HOMESTEADING 89

was that Borsodi charged homesteaders

for "bookkeeping costs" above

and beyond the portion of their ground

rents allocated for administra-

tive and clerical expenses.50

But undoubtedly the most telling and

persistent contention made by

critics was that Borsodi's leadership

was high-handed and arbitrary and that

he attempted to force homesteaders to

conform to his preconceived

philosophy of homesteading. The Review

reported that he and Miss Nut-

ting pressured homesteaders into

purchasing looms that merely served as

window dressing for publicity and that

they valued docility above crea-

tivity and self-determination. On April

27 the paper accused him of con-

spiring with Miss Nutting, Virginia P.

Wood, his chief supporter on the

Unit Committee, and Paul Cromer,

president of the unit, to prevent

homesteaders from communicating with the

Unit Committee. One version

of the story is that when Borsodi

returned from a trip to Washington and

learned that the Unit Committee had

entertained a protest signed by nine

heads of families in the unit, he had

reprimanded the committee for exceed-

ing its authority. On May 4 the Review

quoted one homesteader as saying:

The powers and functions of the unit as

a self-governing group exist

in name only, and are in reality being

replaced by an increasingly

rigorous paternalism. The spirit of this

paternalism [as exemplified

by Borsodi] is not benevolent. It

is stubborn, somewhat ill-tempered,

and dictatorial. The spirit being

engendered among the homesteaders

as a result is one of resentment.

Nothing could be further from the

ideal of a cooperative community.

Another article on June 8 claimed that

"practically the only piece of farm

machinery in the possession of the first

homestead unit which has been

well-oiled and in good working order,

and always in use during the past

year, has been the steam-roller."51

The Review also publicized an

attempt to evict Leslie M. Abbe, one

of the first to move his family onto the

Shaw Farm in May 1933. Some-

time in June 1934, Abbe and five other

homesteaders wired Secretary

of the Interior Ickes directly to

protest a new loan contract that was drawn

up by Borsodi. Their viewpoint was that

the contract represented the

"culmination of his vicious

domineering tactics destroying individual

initiative, self-respect and

freedom" and was "subversive of all social

implications" of subsistence homesteading.

Paul Cromer and the majority

of homesteaders who seem to have

remained loyal to Borsodi tried to

apply the unit's constitutional

provision for eviction by a vote of two-thirds

of the members. Abbe was eventually

ousted after several premature at-

tempts, and when he left, several other

members of the minority followed

him.52

The reaction of the Unit Committee to

these criticisms is difficult

to assess. There is evidence that one

member of the committee, Nathan

M. Stanley of the Stanley Manufacturing

Company and the Univis Lens

Company, was critical of financial and

administrative procedures and of

90 OHIO HISTORY

the discrepancy between Borsodi's claims

and the actual number of families

on the land. Making little headway with

his efforts to have the committee

investigate complaints, he then

corresponded with Ickes after the Dayton

Review's attack on April 20.53 Periodically, there were rumors

of mass

resignations from the committee, but

these may have been due to the

desire of many members to escape the

burden of weekly--and sometimes

even more frequent--meetings, or even to

a feeling that a smaller committee

would be more efficient.54

Two developments in April 1934 were of

significance in the relation-

ship between the Dayton Council of

Social Agencies, the local Unit Com-

mittee, and the homesteaders on the Shaw

Farm. Late in March 1934,

a special committee of the Council of

Social Agencies, undoubtedly stung

by the increasingly vocal criticisms,

recommended that the Unit Committee

be separated from the council and

receive no further administrative funds

from it. The official reasons for the

separation were that the unit had

passed the experimental stage and was

now recognized by the Federal

Government, that the Unit Committee had

become in effect a public

corporation administering public funds,

that it was not the function or

policy of the council to administer any

agency, and that the council was

not properly equipped to exercise

control. But the motivation behind this

recommendation was at least partly to avoid

embarrassment and to retain

public support for its other activities.

Therefore, beginning in April, the

council cut off the homestead project

from its most important organized

local sponsorship.55

The second significant development in

April was a reorganization and

reduction in size of the Unit Committee.

Reorganized as the Unit Com-

mittee of Dayton, Ohio, Incorporated,

after the separation from the Council

of Social Agencies, the committee then

needed a more formal structure

than it had hitherto possessed. Under

some pressure from Borsodi, who

insisted that the Federal Division of

Subsistence Homesteads favored hav-

ing a smaller local body in charge, the

committee finally agreed on April

23 to turn over direct administration to

a five-member board of directors,

which would be theoretically responsible

to a larger twenty-four-member

association of advisers made up of both

local and non-resident persons.

At first, Borsodi suggested that the

five-member board be composed of

Mrs. Wood, Elizabeth Nutting, Walter E.

Joseph, an expert in animal

husbandry from Montana State College who

had become unit manager

in November 1933, Robert DeArmond, and

himself. But objections to

turning policy-making over to such a

committee, three of whose members

were staff personnel, were too strong;

and the board finally selected on

April 23 consisted of Sam H. Thal, as

president, Robert DeArmond, a

salesman, Mrs. George H. Wood, Mrs.

George Shaw Greene, a leading

figure in both local and state units of the League of

Women Voters and

the widow of a partner in the investment

firm of Greene and Brock, and

Mrs. Scott Pierce, an active participant

in civic affairs whose husband was

in insurance--none of whom were staff

members.56

SUBSISTENCE HOMESTEADING 91

By the end of April 1934, the objections

of taxpayers in Jefferson,

Madison, and Harrison townships, the

criticisms by a faction of home-

steaders of delays in construction and

arbitrary administration, the attacks

of the Dayton Review, and the

tensions within the Unit Committee all

reached a climax and came to the

attention of the Division of Subsistence

Homesteads in Washington. At this point,

the fate of the project also

became entwined in a change of Federal

policy that caused the final crisis

for homesteading in Dayton. The

Secretary of the Interior, Harold L.

Ickes, was a man with a passion for

orderly, efficient, centralized admin-

istration. In his direction of the

Public Works Administration, he achieved

a singular reputation for scrutinizing

the expenditure of every public

dollar. At first, he was willing to

accept Milburn L. Wilson's preference

for decentralized administration of the

subsistence homesteads, and the

Unit Committee in Dayton received a

straight loan of $50,000 to be admin-

istered without Federal surveillance.

Although the community in Dayton

was the only one where the Federal Government

never owned the land,

control by local corporations was the

rule in the early phases of the

homestead division's activities.

Borsodi, a dogmatic advocate of decentralized

administration, found it easy to work

with Wilson, who shared his funda-

mental conviction that the success of

homesteading would depend on the

initiative and creativity of the local

communities.57 Increasingly, however, as

Ickes became troubled about Wilson's

executive abilities and about local

problems like those in Dayton, the Secretary

moved toward the decision

that all of the homestead communities

should be brought under Federal

control and that the autonomy of local

homestead corporations should be

checked by Federal managers appointed

for each project. Local corporations,

he felt, lacked any direct financial

responsibility for the projects and there-

fore might not operate them in the best

interests of governmental economy

and efficiency. Consequently, on May 12

Ickes ordered complete federaliza-

tion of the entire homestead program,

and in June he replaced Wilson, who

moved to the Agriculture Department on

June 30, with Charles E. Pynchon,

an official in the Public Works

Administration who accepted the philosphy

of Federal control.58

The trend toward federalization, however,

created a serious dilemma for

the Unit Committee in Dayton, even

before the Secretary's order of May

12. The first unit on the Shaw Farm was

safe from Federal intervention be-

cause there had been no strings attached

to the loan of $50,000. But the

application for an additional $309,400

to finance four other units was to be

governed by the new policy. On April 11,

when Ickes was apparently already

bringing pressure to bear on Wilson to

federalize the projects, Wilson re-

quested authority to draw up loan

contracts, similar to the first unit's con-

tract, in order to implement the

decision of March 3, 1934, giving prelim-

inary approval to four additional units

in Dayton. Ickes approved the request

on April 19.59 But the Unit

Committee began at once to debate the possi-

bility that it would have to choose

between federalization and the $309,400.

Reorganization of the committee in late

April contained overtones of some

92 OHIO HISTORY

disagreement over federalization, which

was discussed concurrently. There

also were rumors that of the new

five-member board of directors, four stood

with Borsodi against federalization and

one, Mrs. Scott Pierce, opposed Bor-

sodi. After numerous meetings, the Unit

Committee voted on May 28 to

reject federalization on the grounds

that it would destroy what the project

stood for: a unique plan of low-cost

housing, self-help through exchange of

labor, the loan basis of land tenure,

land tenure free of speculation, local

selection of homesteaders, and the

autonomy of each homestead group.60

Prior to making this decision, the Unit

Committee attempted to obtain

through its president, Sam H. Thal, some

indication of whether acceptance

of federalization would be a condition

for securing the new loan of $309,400.

The answer from Washington was that no

commitment could be made be-

fore completion of an investigation into

local complaints by the Division of

Subsistence Homesteads. A special

investigator for the division, Harry Jent-

zer, visited Dayton for two weeks in

mid-May, and, accordng to the Dayton

Review, unlike the earlier investigation of W. E. Zeuch,

Jentzer's report

concluded that the situation was

chaotic.61 Whether Jentzer's investigation

influenced or merely confirmed Ickes'

decision to insist on federalization,

the Interior Secretary was adamant in

his conclusion that, while nothing

could be done to force the

federalization of the first unit, no additional

loans would be made without it. Given

the Unit Committee's resolution of

May 28, bargaining came to an impasse.62

Borsodi, however, thought that he saw a

way out. Optimistic over a visit

to Dayton by Lorena Hickok, an

investigator for Harry Hopkins' Federal

Emergency Relief Administration, the

week prior to the Unit Committee's

decision to oppose federalization, he

entered a request to withdraw the loan

application for $309,400 from the

Division of Subsistence Homesteads in

order to seek funds from another agency.

Charles Pynchon, director of the

division, approved the withdrawal on the

condition that the Unit Com-

mittee understood that his agency would

assume no further obligations for

the four new units. On June 14 Ickes

indicated to Senator Robert J. Bulk-

ley that another governmental agency

might provide financial assistance to

the Unit Committee on the committee's

own terms. By June 23, however,

the Secretary was raising questions with

Hopkins about the propriety of "one

branch of the Government permitting an

applicant to withdraw an applica-

tion because of reasonable conditions

that are objected to and then allow

[ing] that same application to be filed

with another branch of the Govern-

ment."63 Borsodi could not get

Ickes to rescind his objection to a substitute

loan, and on June 24 the Unit Committee

decided to sue the Federal Sub-

sistence Homesteads Corporation for

$309,400, claiming breach of contract.64

Borsodi subsequently attributed the

failure of homesteading in Dayton to

two factors: his inability to

communicate his broad goals of adult re-educa-

tion to the participants, and the original

decision to seek Federal funds,

which led to the problems of

"red-tape, absentee bureaucratic dictation and

politics" and to Ickes' breaking of

"the solemn agreement into which he had

entered." At the time of the suit,

he made substantially this same charge

SUBSISTENCE HOMESTEADING 93

against Ickes, despite the fact that the

decision on federalization had been

reached without any binding contractual

obligations on the part of the gov-

ernment to finance the new units. In his

argument against federalization

Borsodi charged that it would have made

the homestead community com-

parable to an Indian reservation, exempt

from local and state taxes and in

danger of the loss of voting rights because

of Federal ownership of the land.65

Rather than go down fighting with

Borsodi, however, the Unit Committee

arranged a conference with Pynchon on

July 2 in Washington and disagree-

ments over federalization were settled

harmoniously. The committee de-

clined to file its intended suit and

instead accepted government control of

the four additional units.66

On July 10 Borsodi left Dayton for his

home in Suffern, breaking with

the Unit Committee because of its

reversal on federalization. The commit-

tee then began to lay plans, in

conjunction with Homer Morris, another

Federal official, to make the transfer

to Federal control. By the end of July

a new Federal manager, Harold Peterson,

was on the scene to supervise the

four new units and to act as adviser to

the first unit, which was to continue

on the original basis of local control.

Peterson had worked in economic and

social redevelopment in rural areas in

the Punjab in North India and came

to Dayton from a position as manager of

the model town of Norris, Tennes-

see.67 Peterson spoke

hopefully of beginning work on four new sites in the

summer of 1935, but those projects never

materialized. Throughout 1935

various governmental agencies made

studies of the first unit, which was

also federalized in September 1934 at

the request of the Unit Committee

and the homestead unit itself. In March

1935, A. A. Wattrous replaced

Peterson as manager, when Peterson

became relief director for Uniontown,

Pennsylvania. Later, in May 1935, the

unit was transferred from the Division

of Subsistence Homesteads to the

Resettlement Administration, when that

agency was created to incorporate the

work of earlier agencies in rural de-

velopment. And on December 30, 1935, the

property was purchased by the

Ohio Rural Rehabilitation Corporation,

which intended to develop it as an

experimental urban community.68

Despite these changes in management and

periodic surveys, however, the

project never became a pioneering experiment

in finding a new balance

between urban and rural life, and early

in 1936 those few homesteading

families still remaining finally

departed.

THE AUTHOR: Jacob H. Dorn is an

assistant professor in the history

depart-

ment at Wright State University.