Ohio History Journal

MARILYN VAN VOORHIS WENDLER

Doctors and Diseases

on the Ohio Frontier

Nineteenth century Ohio historian

Samuel Hildreth ob-

served that "As a class no order

of men have done more to pro-

mote the good of mankind and develop

the resources and natural

history of our country than the

physicians. . . ." Hildreth likely

referred to professional contributions

in the field of natural

science, yet doctors also played an

integral part in bringing

civilization to the frontier. Whether

drawn by spirit of adven-

ture, prospect of personal gain or

increasing Eastern competition,

they accompanied every major wave of

western migration.2 Many

abandoned medicine for more lucrative

pursuits, but a sizable

remainder divided their energies

between fulfilling medical com-

mitments and assisting in the cultural

and commercial develop-

ment of their infant communities.

The pioneer physician needed to be

innovative, adaptable,

and possess great powers of physical

endurance. An example of

such a man was Jabez True, whose life and

career typify that of

the early frontier doctor. During the

early summer of 1788,

True left his medical practice in New

Hampshire to begin life

anew in the Ohio Country. True never

attended a medical col-

lege, yet he became the first resident

physician in the vast area

now comprising the seventeenth state.3

His professional cre-

Marilyn Van Voorhis Wendler is Official

City Historian for the

City of Maumee, Ohio, and is a Ph.D.

candidate and teaches Ohio history

at the University of Toledo.

1. Edmond C. Brush, "The Pioneer

Physicians of the Muskingum

Valley," Ohio Archeological and

Historical Society Quarterly, 3 (1890),

241-59.

2. Ibid. See also U.S. Department

of Health, Education and Wel-

fare, Medicine on the Early Western

Frontier, no. (NIH), 78-358 (1978).

3. Samuel Hildreth, Memoirs of the

Pioneer Settlers of Ohio (Cin-

cinnati, 1852), 330.

Doctors and Diseases 223

dentials were similar to those of his

contemporaries: three years

of preceptorship during which the

student "read medicine" while

he observed and assisted an established

doctor were sufficient

training to earn the title "legal

practitioner" in colonial

America.4 In addition,

True's Revolutionary War experience as

a surgeon on a rebel privateer prepared

him for the rigors of

frontier practice.5

The young doctor's skills were in

immediate demand. The

settlers of Marietta, where True

established residence, suffered

repeatedly from outbreaks of small pox

and fevers.6 Venomous

snake and insect bites were

commonplace, as were burns from the

open fires. Extremities were often

severed or mutilated through

careless use of knives and axes, and

wounds from poisoned ar-

rows were an additional hazard of life

in the wilderness. Doctors

were often faced with situations for

which their eastern training

had not prepared them. On one such

occasion, True was called

to aid a woman in an outlying

settlement who had been scalped

by a band of marauding Indians. He

arrived the following day

after traveling over thirty miles by

canoe. The patient survived,

but the physician left no records

divulging the secrets of his

successful treatment.7

Early inhabitants of the fortified

communities scattered

throughout the Ohio River Valley

existed at a bare subsistence

level. Consequently, a doctor's fees

were seldom collectable and

thus economic necessity forced True to

turn to farming. How-

ever, mounting hostilities between

settlers and Indians expanded

the ranks of militia and brought

additional troops into the area.

When faced with a shortage of

physicians, it was common for

the military to contract with local

doctors. In 1791 True re-

ceived an appointment as surgeon's mate

with a monthly salary

of twenty-two dollars, an additional

sum of money which en-

abled him to continue practicing

medicine.8

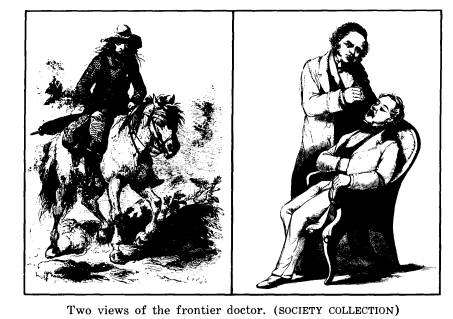

The extent of a frontier doctor's

practice was determined

by the availability of transportation.

Thus, a reliable steed,

4. Frederick Waite, "The

Professional Education of Pioneer Ohio

Physicians," Ohio Archeological

and Historical Society Quarterly, 48 (1939),

191-92.

5. Hildreth, Memoirs of the Pioneer

Settlers, 330.

6. Hildreth, Pioneer History: Being

An Account of the First Exami-

nations of the Ohio Valley and the Early Settlement of

The Northwest

Territory (Cincinnati, 1848), 263, 334, 378-79.

7. Hildreth, Memoirs of the Pioneer

Settlers, 331.

8. Hildreth, Pioneer History, 329.

224 OHIO HISTORY

a sturdy saddle, and waterproof

saddlebags were prime requi-

sites. The bags were connected by a

leather strap which enabled

the bearer to transfer them to his own

shoulders when crossing

high water or traveling on foot. Within

the specially designed

compartments could be found such basis

drugs as calomel-a

derivative of powdered mercury-and

laudanum, a compound

containing opium. Various Indian

remedies, particularly the

popular emetic, Ipecac, were also widely

used.9

Bartin's Materia Medica, an early-nineteenth century medi-

cal book, credits the Indians with the

discovery of medical prop-

erties in such common plants as tobacco,

hemp, and euonymous,

as well as the effectiveness of Peruvian

Bark in the treatment of

Malaria. Additional borrowed recipes

include the various roots:

Grass and Miami combined for tonics;

Blacksnake for liver and

kidney disorders, and Cornsnake for

purifying blood and healing

arrow wounds. Powdered root was mixed

with tobacco or bark

and smoked in a pipe. The amount of the

solid material neces-

sary to effect cure was determined by

the relationship of the

size of the root to the patients's index

finger.10

The primitive conditions under which the

early physician

practiced often forced him to rely upon

his own igenuity and to

adapt many of the procedures used by his

native American coun-

terpart. For example, he used pieces of

sharp flint to make in-

cisions, lance boils, or inject powdered

medicine under the skin.

A deer's bladder fitted with a reed

irrigated wounds or served

as a makeshift enema and the fibers of

the animal's tendons

provided suturing material. Bear's

grease, beeswax, honey and

"mutton suit" served as

ointments and lubricants.11

Simple tools such as knives and bleeding

lancets were the

rule, as few frontier practitioners

posessed more sophisticated

instruments. In one instance, a southern

Ohio doctor, Edward

Tiffin, successfully executed an

emergency amputation in a

wheat field with only his penknife and a

hand saw.12 Anti-

septics and anesthetics were unknown.

When the first ovariec-

9. Howard Dittrick, "The Equipment,

Instruments and Drugs of

Pioneer Physicians," Ohio

Archeological and Historical Quarterly, 48 (1939),

202. Examples of physicians bags, c.

1830s, are in collection of Wyandot

Historical Society, Upper Sandusky,

Ohio.

10. Dittrick, "Equipment,

Instruments, Drugs," 207-09.

11. Dittrick, "Medical Agents and

Equipment Used in the Northwest

Territory," Physicians in the

Indian Wars (Columbus, 1952), unpaginated.

12. Linden F. Edwards, "Edward

Tiffin, Pioneer Doctor," Ohio

Archeological and Historical

Quarterly, 56 (1947), 359-60.

Doctors and Diseases 225

tomy was performed by a pioneer

physician in 1809, both surgeon

and equipment were unsterile and the

woman's only relief was a

few drops of opium.13 Thus,

it is not surprising that patients

often recovered from surgery only to

succumb to resulting in-

fections.

Financial and transportation limitations

restricted the

amount of drugs and equipment which

civilian doctors brought

to the frontier. However, the influx of

troops during the Indian

campaigns eventually brought new

physicians, some fresh from

eastern schools, into Ohio. By

comparison, the army medical

officers were much better supplied.

Surgeon's chests issued by

the government usually contained the

latest drugs and equip-

ment, including marble mortar and

pestles, syringes, bandages

and apothecary scales. Each surgeon also

received a set of

pocket instruments.14 Yet,

the "injudicious assortment of Medi-

cine" received at Fort Washington

led senior medical officer

Richard Allison to complain that

"the greatest part we have ever

been furnished with has been nothing

more than the refuse of

the druggists shops ...."15

In spite of the obvious handicaps of

frontier practice, many

army physicians remained in Ohio after

their tour of duty was

terminated. The establishment of Fort

Washington in 1789 en-

couraged immigration and gave protection

to the adjacent set-

tlement, the precursor of Cincinnati.

Military surgeons Allison

and John Elliot and surgeon's mate John

Sellman cast their lot

with the new community, where they

gained reputations both as

doctors and civic leaders. Allison was

particularly active and

served as county justice of peace while

branching into farming,

commerce, and town development. He later

represented his

county as delegate to the Ohio Medical

Society. By 1800, civilian

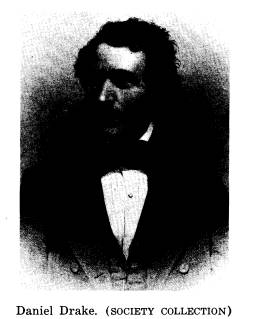

Dr. William Goforth was instructing his

protege, Daniel Drake,

in the art of frontier medicine. Drake,

considered one of Ohio's

most eminent nineteenth century

physicians and urban pro-

moters, contributed immeasurably to the

scientific, cultural and

educational development of the

mid-west.16

13. James Flexner, Doctors on

Horseback: Pioneers of American

Medicine (New

York, 1937), 127.

14. An inventory of an army surgeon's

chest, circa late eighteenth

century, may be found in Physicians

in the Indian Wars, unpaginated.

15. Letter to General Harmar from

Richard Allison, April 16, 1789

quoted in Virginius Hall, "Richard

Allison-Surgeon to the Legion,"

Physicians in the Indian Wars, unpaginated.

16. Ibid.

226 OHIO HISTORY

Meanwhile, in Marietta, the only other

patch of civilization

north of the Ohio River, a similar

pattern was repeated. Former

army physicians Thomas Farley and

Nathan McIntosh remained

in southeastern Ohio to share True's

extensive practice. They

were soon joined by civilian doctors

Josiah Hart, Increase

Matthews, and Samuel Hildreth. Two

immigrant physicians,

former Royal Navy surgeon William

Leonard and former French

citizen John Baptiste Regnier, were

also drawn to the frontier.

By 1821 eleven men shared the medical

practice of Washington

County, and each contributed in

additional ways to the develop-

ment of their communities. For example,

nine held public office,

seven engaged in successful commercial

enterprises, one served

as city architect, and another founded

a rival community.17

As the frontier rolled steadily onward,

the former wilder-

ness became checkered with farms and

towns. The northwest

corner of the state, surrounded by an

almost impenetrable

swampland and hitherto controlled by

Indians and British, re-

mained briefly untouched, but the

conclusion of the War of 1812

removed the final barriers to

civilization. The process of settle-

ment began anew as adventure-bound,

land-hungry settlers

swarmed into the Maumee River Valley.

Physicians were once again in the

vanguard of frontier

society. Among the newcomers was Dr.

Horatio Conant, a young

Vermonter whose life closely paralleled

that of Jabez True, his

predecessor from neighboring New

Hampshire. Neither man

held a prestigious medical degree,

although both were excep-

tionally well educated for the period.

After a rigid classical gram-

mar school education, Conant attended

Middlebury College in his

home state and graduated in 1810. Three

years later he began an

apprenticeship under Dr. Harry

Waterhouse of Malone, New

York, and attended a series of lectures

at Yale University.18 Two

years as a tutor in the East prepared

him as school master to

a handful of Maumee Valley children,

just as True held classes

in a fortified blockhouse almost twenty

years earier.l9 In ad-

dition, both Conant and True acquired

valuable training as mili-

tary surgeons. Perhaps most important,

they believed that their

17. Brush, "The Pioneer Physicians

of the Muskingum Valley,"

243-59.

18. David O. Powell, "The Early

Life of a Pioneer Ohio Physician:

Dr. Horatio Conant, 1785-1816," Northwest

Ohio Quarterly 69 (Summer,

1977), 98-106.

19. Hildreth, Pioneer History, 335.

Doctors and Diseases 227

destines were linked with the future of

the western country and

they determined to work toward its

advancement.20

For thirteen years Conant was the only

resident physician

in an area bounded by present-day

cities of Defiance and Bowling

Green, Ohio, and Tecumseh, Michigan.21

In 1829, he convinced

Oscar White of New Hampshire to enter

into partnership. White

was well qualified. After three years

of preceptorship with his

uncle, Dr. Charles White of New

Hampshire, he graduated from

the medical school at Dartmouth College

and immediately set out

for the West.22 White was

the first Maumee Valley physician

to be fully accredited by the medical

profession, although he was

only twenty years old, less than half

the age of his new partner

from whom he presumably took over many

of the more strenuous

duties. In later years he recalled the

rigors of those days when he

was

... compelled to ride horseback days at

a stretch in order to reach his

patients; fording streams, wet often for

hours and chilled with the

fierce winds; often in winter having

his clothes frozen upon his per-

son, there being no houses to stop at;

riding night and day, summer

and winter, keeping a relay of horses

when needed.23

The 1830s land boom brought additional

immigrants into the

valley and eleven towns were plotted in

a fifteen-mile stretch

along the Maumee River almost

overnight.24 All competed for

commercial supremacy, but only Toledo,25

Manhattan, and the

established communities of Maumee and

Perrysburg were cities

in reality as well as on paper. The new

wave of population in-

cluded at least twenty-five physicians.

Of the thirteen who set-

tled in Maumee, six claimed certified

medical degrees, including

one from Harvard and another from

Boston.26 This is indeed

impressive, since less than 20 percent

of all Ohio physicians held

a medical degree prior to 1835.27

20. Powell, "Early Life of a Pioneer

Ohio Physician," 101.

21. Clark Waggoner, History of the

City of Toledo and Lucas County

(New York, 1888), 542.

22. Horatio S. Knapp, History of the

Maumee Valley (Toledo, 1873),

656.

23. Ibid.

24. Randolph Downes, Canal Days (Toledo,

1968), 56.

25. Toledo was formed from a union of

Port Lawrence and Vistula in

1833.

26. Waggoner, History of the City of

Toledo, 543-47. Additional in-

formation in Maumee Express, 1837-1840.

27. Waite, "Professional

Education," 189.

228 OHIO HISTORY

During the formative years of their

communities, doctors

served in many capacities outside the

field of medicine. For

example, while serving as schoolmaster,

Conant also established

a profitable mercantile partnership in

Maumee City. In succeed-

ing years he served as postmaster,

mayor, founder of the local

Whig party-he also served on its

central committee-and was

the first clerk of the Lucas County

Court. In addition, he dealt

in real estate, held stock in the

Maumee Insturance Company, and

was a member of the local merchant

association. Both Conant

and White helped organize the first

county medical society and

served as president and vice-president,

respectively.28

Available evidence indicates that at

least nine of the other

eleven physicians practicing in Maumee

in the 1830s were in-

volved in activities unrelated to their

profession. These supple-

mental interests included real estate,

banking, merchandising,

farming, lumbering, mining, and

wholesale. One doctor owned

the local land agency, while another

operated a popular tavern.

In addition, three served as city

councilmen and four others held

positions as municipal health officers.29

Dr. Erasmus Peck, of

neighboring Perrysburg, was involved in

milling, merchandising,

and banking. He also served as village

mayor, district repre-

sentative in the state legislature, and

state senator.30

Religion also played a part in the

lives of many early phy-

sicians. Doctors and laymen alike

concurred with the philosophy

that "disquitudes and diseases and

untimely death ... spring not

from fulfillment but from infraction of

the laws of God."31 Thus,

medical and theological concepts were

closely intertwined, as

were the roles of physicians and

preachers of the gospel. A few,

such as medical doctor and ordained

minister Edward Tiffin,

combined the vocations. Most, such as

Conant, were content to

be among church incorporators and serve

as vestrymen, lay

readers, and occasional authors of

religious tracts, while men of

the cloth expounded upon the

relationship between moral and

physical well-being.32

28. Marilyn V. Wendler, "Maumee

City: A Study of Urban Develop-

ment in Frontier Ohio" (Master's

Thesis, University of Toledo, 1977),

124-25.

29. Ibid.

30. Commemorative Historical and

Biographical Record of Wood

County, Ohio (Chicago, 1897), 103, 358.

31. Sylvester Graham, "Science of

Human Life," Scientific Tracts

for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge

(Boston, 1836), 212.

32. Waggoner, History of the City of

Toledo, 542-47. See also Brush,

"The Pioneer Physicians of the

Muskingum Valley," 241-59 for biographical

information.

|

Doctors and Diseases 229 |

|

|

|

All but two of the Lucas County physicians completed their preceptorship or attended schools in the East.33 There were no similar institutions west of the Alleghenies until Transylvania Medical College was founded in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1810. Ten years later, the Ohio Medical College was established in Cincinnati. Both schools experienced initial problems obtaining students as well as faculty. Of the first class to enter the Ohio school, only seven completed the full course of study. A mere 30 percent of those attending Willoughby College, founded thirteen years later in northeastern Ohio, graduated during the first ten years of operation.34 Lack of qualified personnel created additional problems for the western medical schools. However, this situation prevailed as far east as Pennylvania where one faculty member of a struggling college noted that "Very few" of his colleagues ". .. ever read a medical book."35 Willoughby was able to attract only three graduated physicians to its ten-man faculty, and only four faculty members previously attended even one session of lec-

33. Wendler, "Maumee City," 124-25. See also Waggoner, History of the City of Toledo, 542-47. 34. Waite, "Professional Education," 189. 35. Samuel D. Gross quoted in Richard Dunlap, Doctors of the American Frontier (New York, 1965), 210. |

230 OHIO HISTORY

tures.36 Among the three

licensed physicians was a Toledo doc-

tor who managed to divide his time

between lecturing at Wil-

loughby and attending to his patients

back home.37 Most doctors

could not afford to sacrifice their

practice for the dubious pres-

tige of a western faculty position.

Daniel Drake, founder and first

president of the Ohio

Medical College, learned his trade as an

apprentice in Cincinnati.

He practiced for eleven years before he

completed the second

session of lectures at Philadelphia and

received his degree.

Drake's frustrating experience convinced

him of the need for

adequate training facilities in the

West. However, the major

opposition to medical schools came from

local doctors who lacked

formal educations and feared competition

from a younger group

of professionally-trained practitioners.

Rivalry and resentment

within the medical community and between

faculties continued

to impede growth of western medical

institutions and limited the

number of Ohio trained physicians for

several years.

Occasionally, the honorary title of M.D.

was conferred upon

veteran physicians who distinguished

themselves in the move-

ment to raise standards of medical

competency. For example,

John Sellman, presiding officer of the

committee which adopted

the "Code of Medical Policy and

Rules and Regulations" for Cin-

cinnati on February 27, 1821, received

this token of respect af-

ter thirty-five years of civilian and

military practice.38 Another

noted recipient of the honorary degree

was Marietta historian,

politician, and doctor, Samuel Hildreth.

When elected to the

state legislature in 1810, Hildreth

promptly introduced a bill

to divide Ohio into five medical

districts, each with three exami-

ners appointed to interview doctoral

candidates and issue licenses.

His proposal, which became law on

January 14, 1812, stipulated

that applicants demonstrate good moral

character, produce evi-

dence of three years preceptorship or a

license from a regional

medical group, and satisfactorily answer

questions pertaining

to a basic knowledge of medicine. It did

not, however, prohibit

practice by unlicensed persons and thus

was replaced on Feb-

ruary 8, 1812, by a statute levying a

five to one hundred dollar

fine for each such offense. The harsher

law also increased the

36. Waite, "Professional

Education," 191.

37. Maumee Express, August 19,

1837.

38. Richard Knopf, "Biographical

Data," Physicians in the Indian

Wars, unpaginated.

Doctors and Diseases 231

number of medical districts to seven,

required the establishment

of a medical society within each

division, and provided for the

incorporation of a state organization

of physicians. In addition,

the law proposed that a medical

convention be held in Chilli-

cothe on November 1, 1812, for the

purpose of exchanging pro-

fessional information among delegates

from each of the dis-

tricts.39

Due to lack of attendance at the

Chillicothe convention,

little progress was made before 1821

when delegates to the Ohio

Medical Convention assembled in

Columbus. During this ses-

sion, members stipulated that

prospective candidates, in addi-

tion to possessing a knowledge of

medicine, be familiar with

Greek, Latin, and mechanical philosophy

as well as certain pre-

scribed textbooks.40 At

least a few physicians recognized that

an effective way to maintain medical

standards was to adopt a

more disciplined educational approach

to their profession.

Neither the efforts of the medical

organizations nor the

remoteness of the frontier towns halted

invasion by medical

charlatans, and by 1833 the state

legislature abandoned all ef-

forts to regulate the practice of

medicine.41 Doctors previously

ignored or rejected as practitioners in

the East quickly found

the unsophisticated westerners easy

prey. Cultists and quacks,

encouraged by the success of the

Botanics and other self-help

societies, spread throughout Ohio.42

The lack of professional

physicians and educational

opportunities provided optimal con-

ditions for acceptance of various

curative claims ranging from

ingenius to preposterous, and no

community was immune.

Frontier newspapers spread the messages

of the cultists

and proclaimed the miraculous qualities

of such cure-alls as

"Dr. Benjamin Brandreth's

Vegetable Universal Pills" or

Stabler's "Expectorant and

Diarrhea Cordial," alledgedly ap-

proved by five hundred physicians !43

According to the Maumee

Express, a Dr. Sherwood developed an "original mode of

prac-

39. Donald R. Shira, "The Legal

Requirements for Medical Practice-

An attempt to Regulate by Law and the

Purpose Behind the Movement,"

Ohio State Archeological and

Historical Quarterly, 48 (1939), 183.

40. Ibid.

41. Ibid.

42. Samuel Thomson received a patent to

administer his "treatment"

which incorporated steam baths and vegetable compounds

and later sold

"family rights" to anyone

willing to purchase his book. The botanics were

particularly numerous in Ohio in the 1820s and '30s.

43. Ohio Whig, November 7, 1840; Northwest

Democrat, March 27,

1854.

232 OHIO HISTORY

tice" termed "Electro

Magneticism." His method was reported

to "set at defiance every practice

heretofore followed. . .."44

By 1850, Aesculapius self-help cults

were popular and local

papers announced the sale of The

Pocket Aesculapius or Every-

one His Own Physician at twenty-five cents a copy or five for

one dollar. Not surprisingly, the

promoter was a "doctor" from

Philadelphia. Even the

"regular," or professional, physicians

advertised their skills in the local

weeklies.45

Lack of statewide success in regulating

medical practices

prompted Maumee Valley physicians to

form their own society in

1840. Over half of the sixteen members

resided in Maumee and

Toledoans comprised the next largest

group. The society, how-

ever, proved largely ineffective as a

regulatory agency, although

it provided means of sharing new

theories and discoveries.46

Even so, medical progress continued to

lag far behind

science. Eastern and western physicians

alike were reluctant to

accept technological advances. For

example, the microscope was

already in limited use during the

1830s, but few medical men were

aware of a relationship between

microscopic particles and di-

sease. Some doctors utilized modern

medical equipment such as

stethoscopes, but most preferred to

rely upon their ears, eyes,

and hands.47 Their skepticism was shared by their patients,

many of whom held deep-seated

prejudices and superstitions

concerning medical practice. A

contemporary writer bemoaned

that "society tends to confine the

practicising physician to the

department of therapeutics and make him

a mere curer of di-

sease" while only a few rise above

". . . the discriminatory en-

couragement which they receive from

society to pursue an ele-

vated scientific career."48 Thus,

although the pioneer physician

practiced under greater physical

handicaps, his intellectual iso-

lation from his urban colleagues was of

little consequence.

In addition, both eastern and western

physicians subscribed

to centuries-old theories of disease.

One popular concept was the

humoral theory which postulated that

disease was caused by an

imbalance of four humors-blood, phlegm,

black bile, and yellow

bile.49 In the seventeenth

century, Thomas Syndenham specu-

44. Maumee Express, August 1,

1838.

45. Northwest Democrat, November

7, 1853.

46. John Killets, Toledo and Lucas

County, I (Chicago, 1923), 653.

47. The stethoscope was not in regular

use in northern Ohio until

after 1835, according to Dittrick,

"Equipment, Instruments, Drugs," 203.

48. Graham, "Science of Human

Life," 206.

49. John Duffy, "Medical Practice

in the Ante-Bellum South," Journal

of Southern History (1959), 54, 55.

Doctors and Diseases 233

lated that a morbific substance entered

the body in particles of

air and tainted the blood. Various

theories evolved from the

basic theme, including the notion that

disorders result from gen-

eral physical weakness or the more

sophisticated speculation

designating the nervous system as the

center of all ailments.50

The course of treatment for all types of

illness was funda-

mentally the same. Barton's Materia

Medica, an early-nineteenth

century drug manual, included only

"astringents, tonics, stimu-

lents, errhines or sternutatory

remedies, sialogogues or salivat-

ing remedies, emetics, cathartics,

diuretics, and anthemintics."51

Drugs of the first three categories were

used to stimulate bodily

functions, while the next two were

employed to cleanse the

system through excessive sneezing and

salivating; the last four

were used to purge the patient.

Additional techniques included

blistering and bleeding, usually in

combination with cathartics.

These procedures were so widely accepted

that one innovative

physician even advocated "bleeding

and carthartic or either" for

a case of "love sickness."52

The age-old practice of bleeding was

accomplished through

the use of lancets, leeches, or a series

of cups. The lancet came

in various forms, but the most widely

used was the spring

lancet which automatically penetrated to

the desired depth.

Heated cups were also used to draw

blood. The lancet cup, a

small brass box holding six to twelve

knives, was the most in-

genius device: at the release of the

trigger, the knives swept

forward, counter to each other; the

physician then applied a

hot cup over the incisions to "suck

out" the blood.53 If the fron-

tier doctor lacked such proper

equipment, the same result could

be obtained using a sharp pointed

bistourie and an animal horn

in the traditional manner of the

Medicine Man.54

Leeches were carried by many doctors and

were spurred

into action through the application of

cream, sugar, or blood

spread over the patient's body. Although

physicians disagreed

on the proper amount of blood-letting

necessary to cure, up to

50. Ibid. See also Jonathan

Forman, "The Prevailing Concepts of

Health and Disease," Physicians

and the Indian Wars, unpaginated.

51. Dittrick, "Medical Agents and

Equipment," unpaginated. Ben-

jamin S. Barton was a professor of

botany and natural history at the

College of Philadelphia; his work was

published in 1810.

52. Becklard's Physiology (Cincinnati,

1855), 75, Collection of

Maumee Valley Historical Society.

53. Madge Pickard and R. Carlyle Buley, The

Midwest Pioneer: His

Ills, Cures, and Doctors (Crawfordsville, Indiana, 1945), 108-10.

54. Dittrick, "Medical Agents and

Equipment," unpaginated.

234 OHIO HISTORY

fifty ounces was commonly

recommended!55 As late as 1888,

a Toledo physician advocated

"Bleed until you think you are

killing the patient and he will get

well."56

If bleeding did not bring about the

desired results, other

means were resorted to. A typical

method of purging was the

administration of large doses of

calomel, a powerful physic.

Physicians and laymen hotly debated the

drug's value. While

one victim of a "bilious"

attack implored "Then, Calomel, thou

great deliverer, come!," its

widespread overuse led another to

plead:

And when I must resign my breath

Pray let me die a natural death

And bid you all a long farewell

Without one dose of Calomel!57

Emetics such as ipecac or tartar

induced vomiting and

diuretics drained the kidneys and

bladder. When the patient

was suitably void of all humors, a

tonic of peruvian bark, or

possibly cherry bark mixed with

whiskey, was given. In the

last stages, a few drops of opium were

administered.58 The

severity of the treatment led more than

one historian to marvel

not that the patients recovered from

the illness, but that they

survived the cure!59

Maumee Valley physicians treated a

variety of disorders

during the 1830s. Infrequency of

bathing or change of apparel

led to skin diseases known as scabies

or "prairie itch."60 In-

juries were still commonplace and

children were particularly

susceptible to cuts and puncture

wounds. Lockjaw was a par-

ticularly serious problem: a home

remedy for this "dreadful af-

fliction" passed on to the readers

of a Maumee Valley paper,

called for the application of strong

"ley" made from wood ashes.61

Epidemics were commonplace. Early

physicians and lay-

men were equally unaware of the germ

theory, and sanitation

measures were primitive and inadequate.

Water for bathing,

55. Pickard and Buley, The Midwest

Pioneer, 110.

56. Waggoner, History of the City of

Toledo, 545.

57. R. Carlyle Buley, The Old

Northwest: Pioneer Period, 1815-1840

(Bloomington, Indiana, 1950), 46.

58. Jo Ann Carrigan, "Some Medical

Remedies of the Early Nine-

teenth Century," Historian, 22

(November, 1959), 69.

59. Pickard and Buley, The Midwest

Pioneer, 113.

60. William J. Petersen, "Diseases

and Doctors in Pioneer Iowa,"

Iowa Journal of History, 69 (April, 1951), 99.

61. Maumee Express, June 23,

1838.

|

Doctors and Diseases 235 |

|

|

|

cooking, or drinking was obtained from the town pump to which an iron cup was attached for the convenience of residents.62 Refuse was disposed of in the streets, while cows, swine, and other domestic animals roamed at large. Windows and doors were screenless, allowing flies and mosquitos to swarm freely. Many otherwise knowledgeable people concluded that effluvia from decaying matter or food contaminated by the sick "floated by the current in the atmosphere, and through the open win- dow,"63 bringing disease to unsuspecting victims. This theory eventually resulted in increased sanitation measures, as commu- nities like Maumee passed ordinances against leaving dead ani- mals or other "filth" in public thoroughfares, restricted live- stock to home grounds, and created boards of health.64 In spite of these efforts, contagious diseases such as Erysip- elas, measles, whooping cough, and diptheria still flourished.65

62. Ibid., July 7, 1838. 63. "Reminiscences" of Amelia Perrin quoted in Commemorative Record of Wood County, 358. 64. Maumee City Council Minutes, March 24, 1839. 65. Commemorative Record of Wood County, 104. See also David Tucker, "Methods of Treatment of Some of the More Common Diseases by the Pioneer Physicians of Ohio," Ohio Archeological and Historical Quarterly, 48 (1939), 214. |

236 OHIO HISTORY

Although smallpox was particularly

virulent, treatment for it

changed little over the years. In 1803,

Dr. Richard Allison ad-

vised a patient to take forty drops of

balsamic tincture on sugar,

morning, noon and night.66 Fifty

years later, the Northwest

Democrat printed a physician's "recipe" which called

for one

gram each of powdered foxglove and

sulphate of zinc "rubbed

thoroughly in a morter . . . with 4-5

drops water. Add: nogg

[sic] or about 4 oz. some syrup or

sugar. One tablespoon of the

mixture was to be administered every

other hour until the symp-

toms vanished.67

Some early physicians practiced

inoculation, using live mat-

ter from smallpox sores, theorizing

that the recipient would

contact a lighter case of the disease.

In 1793, Jabez True is said

to have successfully inoculated the

entire population of Belpre,

Ohio.68 This procedure, in

which the doctor used a pocketknife or

similar instrument to scrape the scabs

and insert matter into

open cuts, had obvious risks. Edward

Jenner's method em-

ploying cow pox vaccine was introduced

into America in 1800

and was in limited use as far west as

Cincinnati a year later.

However, tradition died hard and three

years later that city's

council resorted to levying fines

against persons who continued

to use the earlier method.69

Outbreaks of smallpox in 1837 prompted

the government

to commission Dr. White to conduct a

mass vaccination program

for the departing Ottawa Indians of the

Maumee Valley. White

later described their suspicion and

terror of the procedure,70 a

reaction which, although prompted by

primitive superstition,

was not unlike that of many frontier

residents who believed that

vaccination was contrary to divine

will. Although incidents such

as one in which a southern Ohio doctor

was beaten by his neigh-

bors for vaccinating his own family71

became less common, the

general public remained skeptical for

many years.

Diseases such as pluerisy and pneumonia

afflicted most pio-

neer families. A common remedy

consisted of bloodletting, fol-

lowed by a "gentle" purging

with calomel and a few grains of

66. Hall, "Richard Allison," Physicians

in the Indian Wars, un-

paginated.

67. Northwest Democrat, March 27,

1854.

68. Hildreth, Pioneer History, 391-92.

69. Hall, "Richard Allison," Physicians

in the Indian Wars, un-

paginated.

70. Brush, "Pioneer Physicians of

the Muskingum Valley," Ohio

Archeological and Historical Quarterly, 241.

71. Knapp, Maumee Valley, 656.

Doctors and Diseases 237

opium to control the cough.72 Consumption

was also prevalent.

Physicians disagreed upon its most

effective treatment and the

disease defied their efforts to control

it. Most doctors followed

the traditional pattern of bleeding and

purging, but others ad-

vanced more novel methods. One doctor

informed Maumee Val-

ley residents that he "treated

sufferers" for over twelve years

and was ". . . not aware of having

lost four to five patients."

His miracle cure consisted of

"nauseating" doses of one-half

grain sulfate of copper to five grains

gum ammonia with one

teaspoon of water.73 In the

event the remedy was ineffective, the

nausea was perhaps calculated to keep

the patient too occupied to

dwell on the symptoms.

By far, the most widespread complaints

throughout the en-

tire northwest territory concerned the

fevers and a form of

malaria called "ague."

Malaria, typhoid, typhus, and yellow

fever were referred to as intermittent,

remittent, continued, or

autumnal fevers. Treatment was much the

same for all and

usually called for bleeding, followed

by doses of chincona or

quinine.74 Although ague was

known throughout all the states,

it was particularly prevalent in the

swampy lowlands bordering

the Maumee River. An early settler

recalled that by fall entire

families who arrived the previous

spring were "taken down so

that there would not be enough well

persons to take care of

those who were sick."75

The inhabitants of the valley accepted

the onset of the ague

season as inevitable. One Wood County

physician remembered

that:

The ague usually came on every other

day, and when there was not peo-

ple enough they had to have it

everyday, for sometimes there appeared to

be about two agues for one man; and

oftentimes they had to have it

twice a day.76

The chills and sweats struck with such

regularity that in some

communities work schedules, and in extreme

cases church serv-

ices and court sessions, were planned

accordingly.77 In spite of

the inconvenience, the settlers

retained their sense of humor,

as illustrated by a local parody:

72. Tucker, "Methods of

Treatment," 217.

73. Maumee Express, May 20, 1837.

74. Tucker, "Methods of

Treatment," 217.

75. Perrysburg Journal, March 13,

1869.

76. Commemorative Record of Wood

County, 102.

77. Pickard and Buley, Midwest

Pioneer, 17.

238 OHIO HISTORY

On Maumee, on Maumee,

'Tis Ague in the fall;

The fit will shake them so,

It rocks the house and all.

There's a funeral every day,

Without a hears of pall;

They tuck them in the ground

With breeches, coat and all !78

Fortunately, ague was rarely fatal and

one had only to

survive the fits and wait until an

immunity to "the baneful in-

fluence of Miasmi" developed.

Meanwhile, frontier families

swallowed quantities of quinine and

ipecac during the sickly

season.

Most of the maladies which afflicted

the mid-westerners

were age-old and, although physicians

did not yet know how to

control them, their familiarity made

them seem less frightening.

In 1832, Asiatic Cholera invaded the

United States. The disease

traveled to Detroit with General

Scott's troops during the Black

Hawk uprising and spread throughout

Ohio. The suddenness

with which it struck caused confusion

and terror among the

populace. One Maumee resident observed

that "people fall down

as they walk through the streets as

though they were intoxicated.

They are talking one minute and then

they fall down in the

next."79

Doctors throughout the country were as

uncertain about

the treatment of the epidemic as they

were the cause, and they

were no better informed when the

disease reappeared in 1849.

The prestigious Dr. Drake leaned toward

a theory of minute

invisible animalculae, even as he clung

to bleeding as a cure.80

Most practitioners agreed, including a

Toledo doctor who re-

affirmed in 1888 that "If I

treated cholera now I would bleed

and save my patient."81

Another local physician espoused a pro-

cedure in which he injected a large

amount of saltwater into

the victim's veins and then restricted

liquids to cold water only.

Unfortunately, the "cure" was

insufficient to save the origi-

78. Maumee Express, June 6, 1837.

79. Letter from 0. C. Geer to relatives,

May 1832: family papers and

memorabilia, estate of Mrs. John Botte,

Maumee, Ohio.

80. Zane L. Miller and Henry Shapiro, Physician

to the West: Selected

Writings of Daniel Drake on Science

and Society (Lexington, Kentucky,

1977), 373-75.

81. Waggoner, History of the City of

Toledo, 545.

Doctors and Diseases 239

nator who fatally contracted the

disease while ministering to his

patients.82

Considering the prevailing concepts of

disease and treat-

ment in the pre-Civil War period, it is

little wonder that era is

often referred to as the "heroic

age" in medicine. Although more

enlightened men cautioned that "it

is wrong to abuse the proverb

that desperate diseases require

desperate remedies," the adage's

prescription predominated well into the

nineteenth century.83

Still, somewhere between the cultists

and the extremists

were rational practitioners who looked

forward to a time when

technology would boost their profession

to the level of science.

Usually underpaid and overworked, they

were subject to the same

privations as their patients. In 1811,

Tiffin aptly expressed the

sentiments of many of his colleagues

when he lamented, "I shall

not long be able to undergo the

drudgery of country practice. It

is too hard on me."84 The

conditions under which western doc-

tors practiced showed scant improvement

over the next few

decades. The physical demands of the

occupation, particularly

the grueling rounds on horseback and

constant exposure to di-

sease, drained the physicians' health

and often led to premature

death.85

Moreover, doctors were sometimes

unappreciated by their

own contemporaries. During a funeral

oration for a "Beloved"

Maumee Valley physician, the speaker

charged, "It is getting

fashionable to ridicule and deprecate

the medical profession,"

and added that most people ". . .

never half appreciate the hard-

ships, trials, danger, self-denials,

and rewards of the good

physician."86

Perhaps Samuel Hildreth exaggerated

when he asserted that

"wherever the well educated in

that profession are found, they

are uniformly seen on the side of

order, morality, science, and re-

ligion,"87 but it is apparent that

as a group, physicians were sub-

stantially involved in efforts to raise

medical, cultural, and eco-

nomic standards on the frontier. In

addition, their educational

82. Ibid., 542.

83. P. M. Donalson, A. M.,

"Education of a Woman-Its Obstacles

and Necessities," Ladies

Repository, January, 1857.

84. Letter from Edward Tiffin to the Supporter,

October 31, 1811.

85. Two of the early Maumee Valley

physicians died as the result of

falls from a horse. Others succumbed to

various fevers, pneumonia, and

epidemic diseases such as cholera and erysipelas.

86. Northwest Democrat, November

27, 1852.

87. Brush, "Pioneer

Physicians," 241.

240 OHIO HISTORY

background prepared them for positions

of responsibility and

leadership which they willingly

accepted. Edward Tiffin pro-

vided the ultimate example of civic

participation in his rise from

country doctor to first governor of

Ohio. Furthermore, lesser-

known men such as Horatio Conant and

his colleagues helped

push back the frontier in their own

political spheres. Despite the

physical and intellectual handicaps

under which they labored,

Ohio's pioneer doctors remained

dedicated to their profession

and their communities and thus played a

crucial role in the de-

velopment of the state's frontier.