Ohio History Journal

ROBERT M. MENNEL AND STEVEN SPACKMAN

Origins of Welfare in the States:

Albert G. Byers and the Ohio

Board of State Charities

For the past fifteen years, government

programs to aid poor and

dependent people have been attacked by

both liberals and conser-

vatives. In the 1960s, a coalition of

academics and social workers

formed the welfare rights movement to

criticize the inadequacy of

New Deal and Great Society programs and

to propose various strate-

gies to bring about a guaranteed

national income. Because welfare

rights advocates were unable or

unwilling to form alliances with mod-

erate groups, the guaranteed income

never materialized. An alliance

of liberals and conservatives defeated

President Nixon's welfare re-

form plan in 1969 while the liberal

agenda itself was decisively reject-

ed in the Presidential elections of

1972 and 1980. Ronald Reagan's

election signified the ascendancy of

conservative criticisms that wel-

fare programs have been too generous,

going well beyond assistance

to the "truly needy" and

encouraging able-bodied people not to

work. Conservative plans to trim

benefits and eliminate programs ap-

pear more likely to succeed than the

liberal effort to secure a guaran-

teed national income. The question

remains whether either approach

contributes to the stability of the

polity.1

Robert M. Mennel is Professor of

History, University of New Hampshire. Steven

Spackman is Lecturer in Modern History,

University of St. Andrews, Scotland. The au-

thors wish to acknowledge support from

the Central University Research Fund of the

University of New Hampshire, the British

Academy and the Carnegie Trust for the Uni-

versities of Scotland, and the

assistance of Larry Gwozdz and Frank Levstik, formerly of

the Ohio State Archives. This article is

dedicated to Robert H. Bremner, Professor

Emeritus, The Ohio State University,

whose scholarship in social welfare history con-

tinues to enlighten us all.

1. The literature on this subject is

immense, but see especially Frances Fox Piven

and Richard Cloward, Regulating the

Poor: The Function of Public Welfare (New York,

1971) for the welfare rights point of

view and Martin Anderson, Welfare: The Political

Economy of Welfare Reform in the

United States (Stanford, 1978) for the

conservative

rejoinder. Anderson heads President

Reagan's Domestic Policy staff. See also Daniel P.

Origins of Welfare

73

To gain perspective on the tendency of

debate to polarize and mod-

erate policies to founder, we have

sought a vantage point removed

from contemporary controversies yet

related to them. A case study

analysis on the development of welfare

as a state responsibility in the

nineteenth century fulfills our purpose.

Compared with current feder-

al programs, early state welfare had a

narrower scope and authority.

Inspection of local and state

institutions was often contested while

non-institutional aid and services were

non-existent at the state level

and amounted to little more than

sporadic handouts in local jurisdic-

tions. But we share with our ancestors a

belief that poverty is a prob-

lem amenable to reduction if not

elimination. Like us, they had a

range of choices to make and, in

developing their responses, they of-

ten rejected moderate courses of action.

The comparison is

worthwhile.

Recent work on the history of social

welfare in the United States

has tended to assume a national

perspective, either in the interests of

coverage or because the authors have

been convinced that a unified

point of view toward social issues

existed among those nineteenth-

century Americans who were willing and

able to take action.2 While

not disputing the value of these

studies, we hope to illuminate the

subject more fully by examining the

early years of public welfare in

Ohio. We shall focus particularly on the

career of Albert Gallatin

Byers (1826-1890), who served as the

first Secretary of the Ohio

Board of State Charities (BOSC) from

1867 until his death.3

Several factors governed our choice of

Ohio. The state's diversi-

fied population and economy seemed a

suitable example of northern

Moynihan, The Politics of a

Guaranteed Income: The Nixon Administration and the Fam-

ily Assistance Plan (New York, 1973) and Christopher Leman, The Collapse

of Welfare

Reform: Political Institutions,

Policy and the Poor in Canada and the United States

(Cambridge, Mass., 1980).

2. For the survey approach, see James

Leiby, A History of Social Welfare and Social

Work in the United States (New York, 1978). David Rothman, The Discovery of

the Asy-

lum: Social Order and Disorder in the

New Republic (Boston, 1971) and Conscience

and

Convenience: The Asylum and its

Alternatives in Progressive America (Boston,

1980) epit-

omize interpretations portraying

reformers as if they were of one mind. Examples of more

focused studies are Richard W. Fox, So

Far Disordered in Mind: Insanity in California

1870-1930 (Berkeley, 1978) and Gerald N. Grob, The State and

the Mentally Ill: A History

of the Worcester State Hospital in

Massachusetts, 1830-1920 (Chapel Hill,

1966). Older

studies recapitulate laws and

administrative policies and pay little attention to social con-

text. See Frances Cahn and Valeska Bary,

Welfare Activities of Federal, State, and Local

Governments in California, 1850-1934 (Berkeley, 1936); David Schneider and Albert

Deutsch, A History of Public Welfare

in New York State, 1867-1940 (Chicago, 1941).

3. Gerald N. Grob, "Reflections on

the History of Social Policy in America," Re-

views in American History, VII (September, 1979), 293-305 has proposed case

studies as a

means to shed new light on the subject.

74 OHIO

HISTORY

and midwestern conditions.4 Moreover,

there survives an excellent

combination of materials describing the

topic in the state documents,

which outline the structure of public

finance and inspection, in the

BOSC reports (written by Byers), which

graphically portray condi-

tions in the institutions and conflicts

between local governments and

the state authorities, and in Albert

Byers's own diaries and a brief

but interesting file of letters sent to

him in his official capacity.5 When

these materials are used in conjunction

with the annual reports of the

National Conference of Charities and

Correction, it becomes possible

to reconstruct what we think is an

illustrative portrait of the formative

period of state welfare.

The bill creating the Ohio Board of

State Charities in 1867 was ad-

vocated by Republican Party reformers

who controlled state politics

for the better part of two decades,

beginning in 1855 with Salmon P.

Chase's election as governor.6 Three-time

governor, and later Presi-

dent, Rutherford B. Hayes was the other

major figure in this group.

The reform faith that the state should

encourage education, relieve

disease, reform the wayward and aid the

victims of war had pro-

duced a substantial number of

institutions by the end of the Civil

War. Three insane asylums, a

penitentiary, a blind asylum, a reform

school for boys, a deaf and dumb asylum,

and an institution for the

"idiotic" were in operation

while a fourth insane asylum, a soldiers'

home, and a soldiers and sailors'

orphans home were about to open.

There was active discussion on the need

for a girls' reform school

4. Few southern states created charity

inspection authorities before 1900, largely

because the number of institutions to

inspect was so small. By the late 1920s, however,

with southern urbanization and

industrialization well underway, Sophonisba P. Breck-

inridge reported "central

supervisory authority" in all but three states (Mississippi,

Nevada and Utah) and everywhere a trend

toward increasing the coercive power of this

authority. See Sophonisba P.

Breckenridge, "Frontiers of Control in Public Welfare Ad-

ministration," Social Service

Reviews, 1 (1927), 84-99. For further evidence of Ohio's typ-

icality see Robert H. Bremner, ed., Children

and Youth in America, I (Cambridge, 1970),

639-50; Ibid., II. 250-58:

Sophonisba P. Breckinridge, ed., Public Welfare Administration

in the United States: Selected

Documents, Second Edition (Chicago,

1938), 237-364.

5. A series of diaries belonging to

Byers are in box 5 of the Janney Family Papers,

Ohio Historical Society (OHS). He seems

to have used them as an aide-memoire and

they consist largely of brief factual

entries and a meticulous detailing of expenses. Subse-

quently, some of them were used for

other purposes, the 1864 volume, for example, for

press clippings from 1868. These in turn

have been annotated, probably much later to

judge from the hand. See also notes 21

and 37.

6. Ohio. Laws. LXIV (1867)

257-58: Ohio. House Journal (1867), 624. Ohio was the

third state to establish a charity

board, following Massachusetts (1863) and New York

(earlier in 1867). Seven other states

(North Carolina, Illinois, Rhode Island, Wisconsin,

Michigan, Connecticut and Kansas)

followed suit by 1873. For an excellent summary of

the various circumstances shaping the

development of these boards, see Gerald N.

Grob, Mental Institutions in America:

Social Policy to 1875 (New York, 1973), 270-92.

Origins of Welfare

75

and an "intermediate"

reformatory for male first offenders. In addi-

tion, the state paid annual subsidies to

the Longview Insane Asylum

(Cincinnati), Miami University and Ohio

University, while further ex-

penditures were likely as Civil War

veterans aged and as the state re-

sponded to the Morrill Act, which

granted to states the proceeds of

federal land sales for the establishment

of public colleges and univer-

sities. It must be added that although

these institutions were cre-

ated by one political faction, their

incorporation, like that of the

BOSC, received broad bipartisan

legislative support.7

But why was it necessary to create a state

authority to inspect pub-

lic institutions? Two reasons stand out.

First, legislators, pressured by

local philanthropic groups, had been

forced to take cognizance of

the generally dreadful conditions of

county and municipal jails and

infirmaries (almshouses). As the

incorporator of these governments,

the state had a legal obligation to

inspect their institutions and to pre-

vent cruel treatment and neglect.

Second, and of greater concern, leg-

islators felt increasingly unable to

control costs and monitor condi-

tions in the state institutions. A state

board of charity would, it was

hoped, bring local institutions up to

minimal standards, whittle

down the budgetary requests of the

various state institution trustee

boards and root out corruption wherever

found.8

A brief analysis of the financial and

governmental structure of late

nineteenth-century Ohio provides

pertinent background information

on these problems and thus the means for

explaining why the mis-

sion of BOSC was substantially

compromised from the outset. We be-

gin with two generalizations: First,

local government (that is, coun-

ties, townships, municipalities and

school districts) raised and spent

most of the public monies. Second,

though state expenditures were

therefore relatively small, a

significant and growing proportion of its

budget was devoted to education and

welfare expenses. Both of

these points require development.

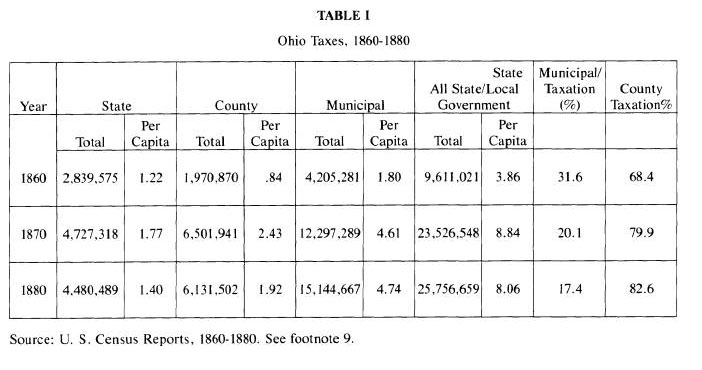

Table I, a summary of taxes collected by

local and state govern-

ment from 1860 to 1880, indicates the

local predominance.9 In 1860

7. For an example of legislative

approval of institutions, see Robert M. Mennel, "The

Family System of Common Farmers': The

Origins of Ohio's Reform Farm, 1840-58,"

Ohio History, LXXXIX (Spring, 1980), 131-34.

8. Ohio. House Journal (1867),

204-35, 624 and appendix, 235-37. An analysis of cor-

ruption at the state level is John P.

Resch, "The Ohio Adult Penal System, 1850-1900: A

Case Study in the Failure of

Institutional Reform," Ohio History, LXXXI (Autumn,

1972), 236-63.

9. Table I drawn from the following

sources: U.S. Census. Statistics of the United

|

76 OHIO HISTORY |

|

Origins of Welfare 77 |

78 OHIO HISTORY

county and municipal taxes were twice as

high as state taxes and the

difference increased during the decade.

County taxes increased at an

average annual rate of 23 percent, while

the municipal increase was

nearly 20 percent. County and municipal

taxation combined to ac-

count for over 80 percent of all public

levies by 1870, a proportion

which held steady in 1880 (and even into

the twentieth century).10

For state taxes the average annual

increase during the 1860s was less

than 7 percent, and the state percentage

of all taxation shrank from 32

to 20 percent, a share that declined

further by 1880. The municipal

burden remained the most substantial,

increasing during the 1870s

on both a total and a per capita basis,

while state and county taxes

decreased in both categories.

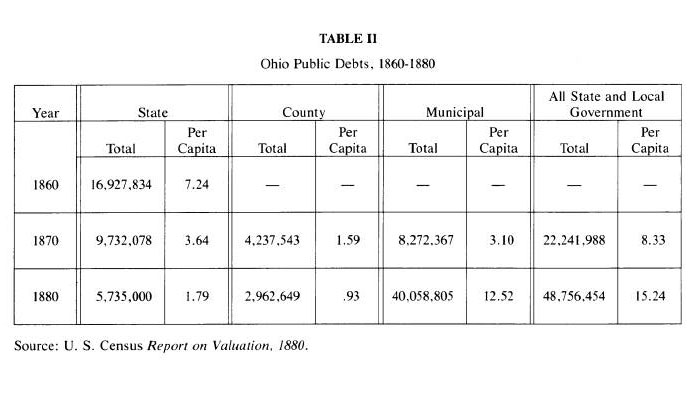

Table II, Ohio Public Debt from 1860 to

1880, emphasizes the

stress on municipalities. The figures

clearly show debt declining at

the state and county level while

climbing sharply in the towns and

cities.11 This was due, on the one hand,

to the retirement of state ca-

nal bonds and the completion of county

jails and infirmaries, and on

the other hand, to the capital

expenditures for the schools and pub-

lic works needed to meet the demands of

an urbanizing population.12

Although state taxation and debt were

declining in relation to local

burdens, welfare spending was creating

pressure upon available reve-

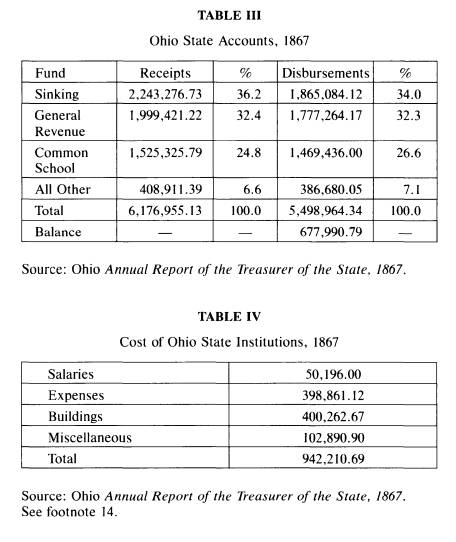

nue. The structure of state finance is

illustrated in Table III; 1867 is an

apt year since the BOSC was established

then. Of a series of separate

funds, whose income and expenditure were

kept independent from

each other, the three most important

were the Sinking Fund, the

General Revenue Fund, and the Common

School Fund. In 1867,

these funds accounted for more than 90

percent of both receipts and

disbursements.13

General revenue was the crucial account.

Representing about a

States in 1860. Mortality and

Miscellaneous Statistics (Washingtion,

D.C., 1866), 511;

U.S. Census, Eighth Census. The

Statistics of Wealth and Industry of the United States

(Washington, D.C., 1872), 11, 51; U.S.

Census. Ninth Census. Report on Valuation, Tax-

ation and Public Indebtedness in the

United States (Washington, D.C.,

1884), 25.

10. U.S. Census Bureau. Wealth, Debt

and Taxation (Washington, D.C., 1907), 767,

967-69. Ohio law allowed county

commissioners to hire "tax inquisitors" to pursue

evaders. The inquisitors were paid a

percentage of the amount they enabled the govern-

ment to recover.

11. U.S. Census. Ninth Census. Report

on Valuation .., 284-85, 612-13. County

and municipal figures are unavailable

for 1860.

12. These taxation and spending patterns

followed national trends. See U.S. Census

Bureau. Wealth, Debt and Taxation,

1913 (Washington, D.C., 1915). On the impact of ca-

nal building on Ohio finance see Harry

Scheiber, Ohio Canal Era; A Case Study of Gov-

ernment and the Economy, 1820-1861 (Athens, Ohio, 1969).

13. Ohio. Annual Report of the

Treasure of State (1867), 9.

|

Origins of Welfare 79 |

|

|

|

third of the total budget, it was supported by a general property tax and met the day to day running expenses of the state government. Its major commitments were salaries, legislative costs, and the expenses of the state institutions. Institutional costs, outlined in Table IV, made a decisive impact upon the state budget. In 1867, institutional build- ing and operating expenses accounted for 53 percent of disburse- ments from the General Revenue Fund-that is, more than than half the everyday operating costs of the state government-and 17 percent |

80 OHIO HISTORY

of disbursements from all funds.14 More

important, these costs

could not be controlled as easily as the

state's other major obliga-

tions, the Sinking Fund and the Common

School Fund. Although

these two funds accounted for 60 percent

of total disbursements in

1867, the Sinking Fund was declining in

importance as the canal

bonds were paid off while school

expenses were curtailed by the re-

quirement that localities bear the brunt

of costs. By contrast, legisla-

tors were annually beseiged for funds by

institutional trustees with

costs escalating to the point that

several delegates to the State Consti-

tutional Convention of 1873 feared state

insolvency.15

The situation was further complicated by

the fact that appointment

of institutional trusteeships

represented one of the few sources of pa-

tronage for the state's chief executive.

The state constitution denied

the governor a veto and allowed him only

a few appointments. Even

the trustee appointments had to be

confirmed by the state senate.

Thus, with each change of

administration, "reorganization" of trus-

tee boards was always a possibility.

Institutional trusteeships were

highly priced even though unpaid. Not

much could be made from

per diem expenses, but the offices conferred or recognized

status,

carried their own appointing power over

institution staff, and even

though trustees were barred from direct

commercial connection with

their institutions, they did determine

the placing of contracts. The

net effect was to create support for the

institutions and their programs

in both the legislative and executive

branches and thus dilute the

impact of cost cutting and efficiency campaigns.16

Given both the preponderance of local

government and the politi-

cal power of state institutions, it was

no surprise that in debate on the

bill to set up the Board of State

Charities, legislators weakened the

draft in order to protect their own

financial and political interests, to

cut costs and to leave patronage

undisturbed. The original bill pro-

vided the board with the services of a

modestly paid executive sec-

retary who was empowered to:

14. Figures recombined from the detailed

list of disbursements from the General

Revenue fund, Annual Report of the

Treasurer of State (1867), 12-15. This detailed listing

gives a total differing from that of the

summary recapitulation reproduced as Table III.

The recombination here has used the

detailed listing.

15. Ohio. Official Report of the

Proceedings and Debates of the Third Constitutional

Convention, I, part 3 (Cleveland, 1873-74), 200-38.

16. Most of the surviving Governors'

Correspondence for this period in the Ohio

State Archives is closely concerned with

patronage. Though fragmentary and damaged

by fire, these files are a mine of

tantalizing information.

Origins of Welfare 81

investigate and supervise the whole

system of the public charitable and cor-

rectional institutions of the state, and

counties, and shall recommend such

changes and additional provision as they

may deem necessary for their eco-

nomical and efficient administration.17

In the legislative give and take,

however, the words "supervise" and

"counties" were deleted,

leaving trustee boards unchallenged and

the localities subject to discretionary

rather than mandatory visits.

The power to inspect technically

remained because the state char-

tered local government and occasionally

subsidized local institutions,

but with the additional removal of the

provision for a paid secretary

the likelihood of regular inspections

appeared remote.

The law that emerged from debate, then,

confined the Board of

State Charities (whose members were to

draw only expenses) to visi-

tation and the gathering of information.

In this respect, the BOSC

was treated only slightly worse than

other state agencies. The Gas

Commissioner and the Inspector of Steam

Boilers had to use their

salaries and personal funds to purchase

testing equipment, while the

Inspector of Mines pleaded in vain for

one assistant to help him con-

duct inspections.18 In short,

these early boards and commissioners

were armed mainly with the weapon of

publicity. Personal conviction

and administrative skill would be the ingredients

of whatever suc-

cess they might achieve.

The first trustees of the Board of State

Charities suitably repre-

sented the reform wing of the Republican

party. Foremost among

Governor Jacob Cox's appointees in 1867

was Joseph Perkins, a

Cleveland banker, philanthropist and

railroad founder. Robert W.

Steele of Dayton helped organize the

first state agricultural fair and

tirelessly promoted public libraries and

higher education. Douglas

Putnam of Marietta had a distinguished

Civil War record and, like

the others, had formed his allegiance to

the Republican Party in the

anti-Nebraska agitation of the

mid-1850s. The other major figure of

the early board was John W. Andrews, a

Columbus lawyer who was

appointed by Governor Rutherford B.

Hayes in 1870. Representing

different parts of the state, these men

were united in belief-as Prot-

estants (Presbyterians or

Congregationalists) valuing good works as a

path to salvation and as Republicans who

saw their party as symbol-

izing God's blessing of the American

people.19

17. Ohio. Senate Journal (1867),

624.

18. Ohio. Docs. I (1867), 247-56;

Ibid., I (1870), 579, 583, Ibid., II(1876), 81-82.

19. Elroy M. Avery, A History of

Cleveland and its Environs, I (Chicago, 1918), 252,

337; The History of Montgomery

County, Ohio (Chicago, 1882), 244-45; History of

82 OHIO HISTORY

The trustees defined their primary task

as soliciting funds from

"private but influential

citizens" in order to pay the salary of an agent

or executive secretary. This position

had been deleted by the legisla-

ture but there could be little objection

since no state funds were in-

volved, at least initially. Practical

but also socioeconomic reasons ex-

plained their course of action. Because

the trustees had extensive

business interests, they could plausibly

claim that they would be

unable to fulfill the law's requirement

of substantive inspection of the

state's institutions. But they also knew

that the law's high moral in-

tent had been substantially compromised

by legislators who had

gutted the power of the board to enforce

its findings. Therefore, the

hiring of an agent would not only save

them time but also allow them

to express their displeasure at

institutional conditions without suffer-

ing directly the opprobrium of being

unable to effect change. What

they required was a person of some

repute who would view the posi-

tion as a promotion.20

Albert Gallatin Byers fulfilled their

needs. In 1867 he was serving

as minister of the Third Avenue

Methodist Church in Columbus and

also as chaplain at the Ohio

Penitentiary. In the latter capacity he

had made a reputation as a persistent

critic of the corruption and cru-

elty dominating the institution.

Penitentiary trustees may have been

glad to loan his services. Certainly,

the BOSC trustees hired him be-

cause of his zeal although their esteem

was measured because he

was poor. Years later, John Andrews

pityingly remarked upon Byers's

threadbare life when recommending him

for other jobs.21

Since Byers would more than repay the

trustees for their confi-

dence, it is worth knowing more about

him. He was born in Union-

town, Pennsylvania, in 1826 of

Scotch-Irish parents. He and his

brother and sister received a strict

Presbyterian upbringing, al-

though Albert became an accomplished

humorist and storyteller

who proudly emphasized his Irish

heritage. After his father's

death, the family moved to Portsmouth,

Ohio, where Byers began to

Washington County, Ohio (Marietta, 1881), 382, 483-85; History of Franklin

and Pickaway

Counties (1880), 68, 563, 566. These trustee positions were

renewable, and Perkins in fact

served for over twenty years.

20. Ohio. Docs., II (1868), 634.

In 1868 Rutherford Hayes gave the Board $500 from

the governor's contingency fund and the

following year the position of secretary was offi-

cially recognized and modestly funded by

the legislature. See Hayes to Joseph Perkins,

August 8, 1868, Governor's Papers, Box

8, The Papers of Rutherford B. Hayes, Hayes

Library; Ohio. Docs., II (1870),

371.

21. Andrews to Hayes, December 5, 1883,

and January 8, 1885, Hayes MS. See also

Albert G. Byers diary, March 15, 18;

April 1; May 1, 31; November 28, 1865, Byers Fami-

ly Papers, Ohio Historical Society

(OHS).

Origins of Welfare 83

study medicine. In 1849, however, he was

enticed by the Argonauts,

a party of gold-hunters heading for

California. He nearly starved to

death on the trek but stayed a year

until news of his mother's death

called him home. Soon thereafter, he

decided "at his mother's

grave" to become a Methodist

circuit rider. Throughout the 1850s,

he served with great success in several

of the impoverished counties

of southern Ohio. Byers was a small

slender man with startlingly

white skin. His high cheekbones and

animated expression made

people think that he was an actor, and

indeed he had a reputation as

a performer in the pulpit. In 1852 he

married Mary Rathbun of

Cheshire, and the first of their seven

children was born in 1854.22

Byers's Civil War experience initiated a

process of self-questioning

which was to last for the rest of his

life. From 1861 to 1863 he served

as chaplain of a Portsmouth volunteer

company that fought at Chick-

amauga and Lookout Mountain. He returned

exhausted from

comforting and treating the wounded but

nevertheless viewed his

ministerial role as somewhat confining

even in the larger town of Co-

lumbus. By the 1860s, Methodism in Ohio

and elsewhere had be-

come an established middle class

denomination. Primarily con-

cerned with promoting temperance,

Methodists were experiencing

ideological confinement as Free

Methodists and pentecostal sects

captured the revivalistic audience while

the Arminian wing drifted

toward various secular causes such as

civil service and charity re-

form. Byers inclined strongly toward

good works and thus eagerly

seized the Penitentiary chaplaincy and

the offer to be secretary of

the BOSC. In 1867 he also stood as

Republican candidate for the

state senate from Franklin county. That

election was bitterly fought

over the issue of black voting rights,

with Democrats throughout the

state charging that Republican support

of manhood suffrage would

inevitably lead to legislated social

equality between the races. In

heavily Democratic Franklin County,

Byers lost by a large margin.23

Byers's militancy was counterbalanced by

his doubt that he, as a

minister, could effect change. He once

wrote Rutherford Hayes urg-

ing a "flinging dirt" campaign

against a local Democratic candidate

22. Ohio State Journal, November

11, 1890; National Conference of Charities and

Correction (NCCC). Proceedings (1891),

243-53.

23. Nelson W. Evans and Emmons B.

Strivers, A History of Adams County, Ohio

(West Union, Ohio, 1900), 342-42; John

Marshall Barker, History of Ohio Methodism

(Cincinnati, 1898), 74-75, 123-28;

Walter W. Benjamin, "The Methodist Episcopal

Church in the Postwar Era" in Emory

S. Bucke, ed., The History of American Metho-

dism, II (New York, 1964), 320-60; William Warren Sweet, Methodism

in American Histo-

ry (New York, 1961), 341-45; NCCC Proceedings (1891), 243-44; Ohio.

Docs., I (1867),

318.

84 OHIO HISTORY

and then discounting his own advice,

"I find myself, preacherlike,

dabbling in politics." Also, he was

loyal to a fault to his benefactors.

Pleading with Hayes to run for governor

in 1875, Byers addressed

him, "not . . . as a Republican. I

appeal to you as a citizen for the

sake of the state. As a man for the sake

of humanity. As a Christian

for the sake of truth and benevolence .

. . [in the hope that] under

God you may be triumphantly

elected." Thus, his willingness to con-

front the opponents of charity

inspection, combined with his eager-

ness to serve the reform wing of the

Republican Party, made him an

ideal choice for secretary of the BOSC.24

Byers's first report was decisive in

tone and emphasis. He

skimmed over state operations with

ritualistic criticism of the Peniten-

tiary and praise for the other

"large and noble Benevolent Institu-

tions". By contrast, he found the

county jails and infirmaries "not

only deplorable but a disgrace to the

state and a sin against humani-

ty."25 In reaching his

judgment he drew upon his years of experi-

ence as a ministerial visitor as well as

his initial inspections for the

Board. He was keenly aware that local

politicians and their appoint-

ees would resent his visits and try to

get him dismissed if he made

critical remarks, but his reports show

why he took the risk.

Albert Byers discovered appalling conditions

in jails as he traveled

about the state. "Fairfield County

Jail-Rathole," reads one entry in

his diary. That one in Trumbull County

was "utterly, indescribably

mean," while the jail in Washington

County was "dark, poorly venti-

lated and miserably kept." Byers

also discovered that the Sheriff of

Union County was using his jail as a

brothel. Filth, vermin and spittle

permeated most of the institutions

visited.26

Perhaps conditions like this were only

to be expected in jails, but

in the Richland County infirmary Byers

found a man whose feet had

frozen off during the previous winter.

In Jefferson County seven na-

ked insane people crouched together in

one cold damp cell. A man in

the Pike County infirmary was covered

with flies. A Ross County

woman had been so contorted by chains

that she could hardly be

distinguished from a pile of rags on the

floor. In Columbiana County

a couple fornicated in the courtyard,

while in Lucas County, a nym-

phomaniac entertained a group of insane

men. In none of these places

24. Byers to Hayes, July 6, 1875, and

April 19, 1875, Hayes MS.

25. Ohio. Docs., (1867), 235-68.

Infirmaries were the county almshouses, usually at-

tached to a farm of about 200 acres

which was the prime inducement in attracting a su-

perintendent and his main interest when

in office.

26. Byers Diary, Byers MS; Ohio. Docs.,

1(1868), 1226-41; Ohio. Report of ... Third

Constitutional Convention, 1, part 3, 200-35.

|

Origins of Welfare 85 |

|

|

|

was there a superintendent present when Byers made his inspec- tion.27 Byers was particularly incensed by the plight of children in these infirmaries. He warned of "the harvest not only to the individual life of the child, but the state, which must be gathered sooner or later from such sowing." After visiting the Hamilton County (Cincinnati) almshouse he reported that he was "unable to give the numbers of little, half-clad, filthy and squalid children that seemed fairly to swarm in the midst of these scenes of unmitigated misery."28 The county spoils system was a major reason for the cool reception Byers often received. Elected directors appointed superintendents at a derisory salary, or let the office to the lowest bidder (a literal case of farming, given the nature of the institutions), who then padded his salary through a judicious choice of institutional contractors and sup- pliers. As the county commissioners and infirmary directors usually took their cut, inmate care was bound to suffer. Byers directly at- tacked the responsible individuals. "Quite inferior men" were often chosen as directors, he said, while most superintendents were "no-

27. Ohio. Docs., I (1868), 674-77; Ibid., II (1869), 803,831-34. 28. Ohio. Docs., II (1867), 268; Ibid., II (1868), 672. |

86 OHIO HISTORY

toriously lazy in habits, selfish in

nature, socially, intellectually and

morally unfit."29

Byers recognized, however, that while

corruption accounted for

much of the inmate neglect, fear and

ignorance also underlay the

hostility that greeted him. A Jefferson

County infirmary director

agreed to a joint tour provided that he

did not have to accompany

Byers inside the building. In Noble

County, inmates had their own

keys, locked themselves in at night and,

Byers concluded, plausibly

considered themselves "an

independent community because of the

distance and remoteness of the

superintendent's house." The infir-

maries were in fact not institutions but

poor homes, often as decrepit

as any in the county. "How are your

buildings ventilated?" asked

Byers in an early questionnaire.

"By air coming in at doors and bro-

ken panes of glass," replied one

superintendent. "Have you any facili-

ties for bathing?" "The Ohio

River is not far off," answered anoth-

er.30

Byers took the humor and pathos of these

episodes as evidence of

popular receptivity to the idea of

benevolent authority. To encourage

this sentiment, he believed that it was

necessary not only to insist

upon his own right of inspection but

also to seek ways of broadening

the impact of his ideas. On his own

powers, Byers minced no words:

Let it be understood that all public

institutions are liable to visitation and ex-

amination at the most unexpected times,

and that abuses will be unsparingly

exposed.

To increase this influence, Byers

effectively utilized women's church

and temperance groups. One of his

principal allies was the Springfield

crusader Mrs. E. D. "Mother"

Stewart, known throughout the state

for her militance and determination.

After a visit to the Clark County

infirmary, she dryly reported to him

that her reception "lacked a lit-

tle of that cordiality necessary to

establish confidence between par-

ties coming together under such

circumstances." Undeterred, Mrs.

Stewart journeyed to the neighboring

Champaign County infirmary

where she initiated the removal of three

childen to the Soldiers' Or-

phans Home in Xenia. In Ross County,

three ladies, delegated by

Byers, started a press campaign against

the infirmary director.31

To capitalize on the sense of shame

evoked by the inspections,

Byers provided specific plans for

improving conditions. These sug-

29. Ohio. Docs., II(1869), 791-93.

30. Ohio. Docs., II (1870), 406,

415-16; Ibid., I (1888), 1226-29.

31. Ohio. Docs., II (1868), 652; Ibid.,

II (1870), 385-89,417; A Biographical Record of

Clark County Ohio (New York, 1902), 86-93; Barker, History of Ohio

Methodism, 191-219.

Origins of Welfare 87

gestions ranged from particular ways of

improving sanitary conditions

to model plans for an entirely new jail

or infirmary. Furthermore, he

vigorously promoted the efforts of

counties and voluntary organiza-

tions to establish, either singly or in

cooperative groups, separate

homes for orphaned and neglected

children.32

Before long, Byers could point to signs

of progress. In 1870 Hardin

County opened a model infirmary and the

McIntyre Children's

Home in Zanesville began its work. More

important, local officials be-

came more receptive to advice. The

Clinton County superintendent

wrote Byers thanking him for

suggestions, while the directors of the

Green County infirmary cooperated at the

cost of "the severest pub-

lic criticism."33

Betterment, however, had a price and

Byers had to pay it. By 1870

opposition to his criticism was mounting

especially in the urban coun-

ties. He had singled out the

institutions in Cuyahoga, Lucas and

Hamilton counties because he believed

that, compared with many of

the rural areas, they had more than

enough wealth and knowledge

to provide decent care. Thus, the

Cuyahoga jail was "an offense,

wholly out of character with the general

intelligence and moral sense

of the community where it is

tolerated." In Athens County, Byers's

report sparked a local investigation

that disputed his conclusions and

demanded an official rebuke. From the

beginning, the BOSC trus-

tees were aware that Byers was ruffling

feathers. They understood

the necessity of critical inspections,

but they also knew that the posi-

tion of executive secretary was

politically fragile. They urged Byers to

spend some time inspecting state

institutions and, in an effort to sooth

relations with the counties, wrote a

letter to him that was printed in

the 1870 BOSC report. The passage

regarding county visitations read

as follows:

You will impress upon the officers who

you meet, that you come as a co-

worker with them, and to aid them by

your suggestions, and not in a hostile,

carping, criticizing spirit ...

The Board endorsed Byers's ideas of

using "good citizens-both

men and women" as visitors but

forbade him from invoking state au-

thority to gain compliance with his

suggestions.34

Byers was willing to focus on state

problems. He bitterly castigated

the lax management and corrupt building

contracts at the Central In-

32. Ohio. Docs., (1868), 627-31; Ibid,,

II (1869), 849-52; Ibid., II (1870), 426-34.

33. Ohio. Docs., II (1870),

359-60, 389-90, 414-15.

34.

Ohio. Docs., II (1868), 652-60, 672-77; Ibid., II (1869),

817-20; Ibid., 11(1870), 317,

376-82, 400; Ibid., II (1871),

48-49, 60; Byers Diary (1870), Byers MS.

88 OHIO HISTORY

sane Asylum (Columbus) that had led to a

fire killing many inmates;

he vigorously promoted the establishment

of an intermediate peni-

tentiary for first time offenders; but

he would not relent in his criti-

cism of county jails and infirmaries.

Indeed, in 1871 he stepped up

his attack on cronyism in the election

of infirmary directors in the

larger counties.35

When the legislature next met, Byers's

job was in jeopardy. The

politicians' strategy was appropriately

devious. Rather than confront

Byers directly, they eliminated the

entire BOSC without formal ex-

planation; but it was well understood

that the protest from the major

counties was responsible, and analysis

of the vote on elimination con-

firms the fact. The senate vote was

24-10; in the house of representa-

tives it was 69-22. Byers's support came

almost entirely from Demo-

crats representing sparsely populated

rural areas. Twenty of the

twenty-two representatives who voted to

retain the Board were Dem-

ocrats and Mansfield was the largest

town in the area favoring Byers.

The delegations from Cincinnati,

Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton and

Toledo, all heavily Republican except

Columbus, voted unanimously

in favor of elimination.36

Some of the counties favoring Byers, for

example Pike and Ross,

had also been severely censured by him.

Unlike the urban counties,

however, these areas took his advice and

improved their treatment

and facilities. Their amenability may be

explained by the fact that

rural almshouses were often little more

than shacks and could easily

be renovated or replaced. By the same

token, a change in superinten-

dents could work wonders in Circleville,

but have less impact in

Cleveland where other indolent and

negligent officers might be re-

tained. The irony of the situation lay

in the fact that the Democrats

who listened to Byers and followed his

advice represented that por-

tion of the electorate which had

rejected his vision of a just society at

the polls in 1867.

The abolition of the Board hurt him

deeply. "From here on no

heart or time for diaries," he wrote.

"Period of 4 years and 2 months

on his own."37 Though

physically ill as well as sick at heart, he re-

35. Ohio. Docs., II(1867),

235-50; Ibid., II (1869), 766-70; Ibid., II(1871), 34-35.

36. Ohio. Senate Journal (1872),

114, 120, 160; Ohio, House Journal (1872), 213-14;

Ohio. Laws, LXIX (1872), 10.

37. Byers Diary (Feb. 15, 1872), Byers

MS. This volume is different in format from

the pocket diaries that Byers carried

about with him. The entries for Feb. 15, including

another "Board of State Charities Law

repealed," are in a much heavier pencil and in a

larger hand. These look like later

annotations, perhaps, in view of the use of the third

person, entered by his wife or his son

Joseph Perkins Byers who took over as Secretary

Origins of Welfare

89

mained undaunted. In later years he

remarked that the legislature

might abolish the Board, but they could

not abolish him. Clearly,

he had come to view charity inspection

as his vocation. Preaching an

occasional sermon but seeking no new

congregation, he worked for

several years, perhaps as a salesman. He

used his spare time to seek

allies who shared his views, above all

his belief that "partizan pur-

poses" [sic] should not be a factor

in the selection of jail wardens and

infirmary directors. Foremost among

these friends were John Jay

Janney and Roeliff Brinkerhoff. Janney,

a Virginia-born Quaker and

former member of the Republican state

committee and Columbus

City council, was also well-connected in

philanthropic circles and

known for his passionate advocacy of

prison reform. Brinkerhoff, a

lawyer-banker from Mansfield, was a

leading figure in the Democratic

party and greatly interested in both

penology and the reform of pub-

lic charity.38

With Janney's assistance, Byers

organized the Prison Reform and

Children's Aid Association of Ohio in

August, 1874. As executive

secretary of the society, Byers resumed

his visitations, although the

voluntary character of the association

gave these a somewhat differ-

ent emphasis. He continued to inspect

jails and infirmaries, with the

usual mixed reception, but placed

special emphasis on encouraging

voluntary groups to establish homes for

orphaned and dependent

children. The twelve homes that had been

established before the

Civil War were all privately organized

and usually served particular

groups. In 1850, Cincinnati, for

example, had five asylums-two

Catholic, one Protestant, one German

Protestant, and one for "col-

ored orphans." Byers sought to

encourage a tolerant approach re-

garding admissions in order to establish

a population base sufficient

enough to support an institution even in

rural areas. By the early twen-

tieth century there were fifty county

homes for dependent children,

and at least as many private refuges.39

Byers did not envision converting his

Children's Aid Association

into a charity organization society

similar to those forming in Ohio

of the BOSC following Byers's death.

38. NCCC. Proceedings (1891),

246; Ohio. Docs., II (1871), 92-93. Byers's obituary

says only that he was "earning his

bread in his own way." The Diary entry for August 5,

1872, reads "canvassing," but

it is unclear whether this refers to selling, seeking allies,

or political work. See also John Fyfe to

Byers, June 7, 1876, Hayes MS.

39. Hayes MS; Box 21, Janney

Family Papers, OHS; Nelson L. Bossing, "History of

Educational Legislation, 1851 to

1925," Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publica-

tions, XXXIX (1930), 285-91; Charles Cist, Sketches and

Statistics of Cincinnati in 1851

(Cincinnati, 1851), 150-55; Samuel P.

Orth, The Centralization of Administration in Ohio

(New York, 1903).

90 OHIO HISTORY

and other states. One of the main

concerns of charity organization so-

cieties was to control the expenditures

of outdoor or home relief, the

suspicion being that

"unworthy" individuals and families avoided

work by applying for food and fuel from

the various charities of the

town or country. The charity societies

did not give aid themselves

but coordinated existing agencies and

required all applicants to sub-

mit to a stringent means test before

gaining any relief. Byers, however,

was more interested in positive

achievements, such as the children's

homes.40

Byers hoped that his group would revive

interest in the BOSC. He

defended the voluntary approach, in a

letter to Hayes, because, "the

politicians could be set at defiance and

a popular sympathy awak-

ened that does not ordinarily respond to

work-however charitable

-done by law." But with Hayes once

again in the governor's chair in

1876, Byers's advocacy of voluntarism

evaporated. The Board was

necessary, he contended, not only

because "good people" support-

ed it but because it could challenge the

power of "the preachers"

who had often opposed the "appeals

for material aid" of the Chil-

dren's Aid Association.41

Certainly, Ohio's welfare problems had

not disappeared with

Byers's dismissal. Indeed, they had

intensified. The recession of

the early 1870s made a decisive impact

on the infirmaries and the ad-

ministration of poor relief. In 1872 the

number seeking admission to

county infirmaries increased by 34 per

cent, while the number sup-

ported by county outdoor relief nearly

tripled. Meanwhile, the disar-

ray of the state institutions was

becoming more apparent, with anoth-

er insane asylum fire and widespread

concern over operational costs.

The 1873-74 State Constitutional

Convention denounced the waste

and inefficiency in state institutions

and desired to revive the Board

of State Charities. The main point of

contention in its extensive de-

bates on the subject was not whether

there should be a new board,

but whether it should be appointed or

popularly elected.42

The Convention changed nothing, however,

because its proposed

Constitution was rejected at the polls,

leaving intact the old 1851

40. Box 21, Janney MS, OHS.

41. Byers to Hayes, November 12, 1875,

Hayes MS.

42. Ohio. Docs., I (1872),

287-88; Ohio Official Report of the . . . Constitutional Con-

vention, I, XXX, 200-38. Another concern about state

institutions, their power to incar-

cerate an individual against his or her

will, surfaced at the Convention, with a reference

to Wilkie Collins's The Woman in

White (New York, 1860), a popular novel of the day

treating this theme. An 1869 case

involving the custodial authority of the Illinois insane

asylum was one reason for the

establishment of a charity board in that state. See Grob,

Mental Institutions in America, 278.

Origins of Welfare 91

charter. This granted permanent state

support only to institutions for

the insane, blind, and deaf and dumb,

although it did not specifi-

cally exclude other state welfare

activity. The way was open, there-

fore, for the rebirth of the Board of

State Charities, and Hayes's

election provided the occasion. With his

encouragement, the legisla-

ture voted by a wide margin to

reestablish the agency.43

The new board differed significantly

from its predecessor. As sec-

retary, Byers received a stipulated

annual salary of 1,200 dollars. The

governor was made ex-officio president,

with the power to appoint six

trustees, three from each party, to

staggered terms. In this way, Roe-

liff Brinkerhoff became a trustee,

joining John Andrews and Joseph

Perkins from the old board. More

important, the BOSC received the

right to at least comment upon "all

plans of public buildings." Byers

regarded his complete lack of power on

this question the most signifi-

cant defect of the first board.44

Byers was the obvious choice to be

secretary of the new board.

He resumed his duties with enthusiasm

and renewed his attack upon

deficient county institutions.

Eventually, he secured passage of a law

providing that county probate courts

appoint a board of visitors

(three of the five members to be women)

to inspect and report on lo-

cal institutions to the BOSC. This

formalized the means by which he

had extended his influence in the 1860s.

Also, Byers began to pay

more attention to conditions in the

state institutions. In 1880, for ex-

ample, he uncovered the efforts of

authorities at the boys' reform

school to hide the fact that a black

inmate had died because of an

overseer's beating. At the behest of

local officials, he encouraged

asylum superintendents to be more

communicative about their ad-

missions procedures, and he tried to

prevent state institutions from

remanding difficult cases back to the

counties.45

One measure of Byers's success may be

found in the file of letters

addressed to him during the period

1884-85. Besides calming dis-

putes between state and local officials,

he provided a reference serv-

ice for institutions seeking to employ

able people and information for

43. Ohio. Senate Journal (1876),

312-13; Ohio. House Journal (1876), 641-42; Ohio.

Docs., I (1876), 764; Ohio. Laws, LXXIII (1876),

165-66.

44. Ohio. Docs., I (1876), and

III (1877), 92. The bipartisan clause as well as the re-

quirement of mandatory submission of

plans were amendments added in 1880. See

Ohio. Laws, LXXVII (1880),

227-28.

45. H. A. Millis, "The Law Relating

to the Relief and Care of Dependents," Ameri-

can Journal of Sociology, IV (1898-99), 185; Ohio. Docs., I (1880),

608-10; Incoming Let-

ters (1884-85), Papers of the Board of

State Charities, Ohio Historical Society. See also

Ohio Docs., I(1876), 776.

92 OHIO HISTORY

citizens from other states searching for

ideas on charity and prison

reform. Among other communications,

Byers received an anonymous

letter offering information on "the

sanitary condition" of the girls' re-

form school and a petition from inmates

of the Knox County infirmary

asking the directors to provide indoor

washing for older inmates and

to delouse the house. The courteous tone

of these letters and the

cordial response of most superintendents

and directors to Byers's in-

quiries marked a significant change from

the early days.46

Despite these successes, life remained

hard for Albert Byers. He

supplemented his meager salary with itinerant

preaching and sought

repeatedly but unsuccessfully to gain a

position with various national

prison reform groups. Commenting upon

his efforts, John Andrews

wrote, "it is probably in his

interest to make the change to a position

that promises greater permanence, with

less turmoil and personal bit-

terness, than his present post which has

brought him necessarily

into collision with the local

authorities of many counties and all over

the state." It was not to be. After

Frederick Wines blocked his ap-

pointment as Secretary of the National

Prison Association, Byers re-

signed from the group, bitterly

lamenting the frustration of "the one

great and all absorbing ambition of my

life."47

Byers did acquire a national reputation

as an expert on public chari-

ty. In 1889 he addressed the National

Conference of Charities and

Correction (NCCC) on the role of the

state boards. Beginning with

Hastings Hart's definition of the board

as "a balance wheel to

steady the motion of the charitable

machinery," Byers elaborated

on the faith animating the movement:

No community in any state throughout

this nation will ever complain of the

cost of meeting the actual demands of

the dependent. They may not approve

of extravagance, but they will not

knowingly tolerate the withholding of that

which is needful. Stealing of public

money may be condemned, malfeasance

or misfeasance may be forgiven; but to

stint the poor is, to the American con-

ception of public duty, an unpardonable

sin.

State boards, he concluded, performed an

"indispensable" service

by checking both "stint" and

"extravagance," and thereby encour-

46. Letter File, Byers MS. 1884-85 is

the only year for which the incoming letter file

has survived, and there is no way of

knowing whether the total of 183 items is complete,

or whether, if complete, it is typical.

Nevertheless, 36 percent of the letters deal with the

Board's contacts with other states and

such organizations as the NCCC, 20 percent deal

with Ohio state institutions, 18 percent

with administration and visiting, 11 percent with

personal cases, 10 percent with jobs,

and 5 percent with requests for speeches and ser-

mons.

47. Andrews to Hayes, December 5, 1883,

and Byers to Hayes, November, 1889,

Hayes MS.

Origins of Welfare 93

aging that state itself to be "at

once merciful and just, as near like

God as any state may be."48

Byers's health was already failing when

he gave this speech. He

was chosen to head the NCCC in 1890, but

collapsed while con-

ducting the closing ceremonies. He

recovered enough to attend an

autumn charity meeting in a wheelchair.

Greeting Hastings Hart, he

said:

This has been a beautiful world. It has

been a joy to live in it, and I have de-

lighted in the friends I have had. At

first it seemed to me as if I would not

bear to go out of the world, as if I had

a work to do that is not done; but that

feeling is gone and I look forward to

the future with as much joy and peace

and delight as I have ever had in my

life.

A few weeks later he died at home.

Andrew Elmore delivered the

eulogy at the next NCCC meeting,

concluding: "Many a man is a nice,

good man in a Conference like this, who

is a tyrant at home. Dr.

Byers was a charming man in his own

family. It was there I loved him

best."49

Albert Byers's life and his career on

the Ohio Board of State

Charities recall a world in which the

relief of human suffering was

regarded not as a problem to be solved

by the state, but as an obli-

gation to common humanity undertaken by

religious and public-

spirited people. There is little

evidence in Byers's career of a commit-

ment to the expansion of state activity

or authority for its own sake.

Indeed, for all his work with state and

local institutions, he remained

convinced that private charities

"are far more efficient and satisfacto-

ry, as a general rule, than public

charities can be." He always relied

on the interpenetration of public and

private agencies, as his Prison

Reform and Children's Aid Association,

his local visiting commit-

tees, and the close links between the

Board of State Charities and

NCCC demonstrate. Members of the

National Conference of

Charities and Correction referred to

their organization as the

"church of divine fragments."

As postmillenarian and Arminian Prot-

estants, they viewed their work as

necessary actions to ensure the

reign of peace and justice before

Christ's second coming and the final

judgement. Since intolerable conditions

and treatment were still evi-

dent in many places, Byers warned, the

millenium was "not so much

at hand as some of us would wish."

The main hope was to sustain

practical efforts and moral pressure.50

48. NCCC. Proceedings (1889),

89-102.

49. Ibid., (1891), 253.

50.

Ohio. Docs., II(1870), 354; NCCC. Proceedings (1891), 247;

Ibid., (1889), 99-102.

94 OHIO HISTORY

This faith has appeared insufficient or

even ominous to the modern

age. Advocates of the welfare state

regard care as a constitutional

entitlement. During the 1960s and 70s,

they influenced the expansion

of the number and variety of public

programs under which people of

all ages and conditions may qualify. At

the same time, they have con-

tinued to criticize the capitalistic

system for its niggardliness. The

conservative reaction, now regnant, not

only questions the concept of

entitlement but, as a self-proclaimed

moral majority, has inaugurated

crusades against day care, school lunch,

and abortion programs that

serve poor and dependent people. Though

presented positively, as

part of a "pro-family" agenda,

the Moral Majority resonates coercive-

ness and meanness perhaps not unlike

that encountered by Albert

Byers in the 1870s.

Historians have contributed less than

they imagine to contempo-

rary debate. They have appeared for the

most part as witnesses for

liberal points of view. Thus,

nineteenth-century charity reform is por-

trayed as a threatening development.

Individuals like Byers are

viewed as agents for dominant social

groups who were intolerant of

Catholics and immigrants and anxious to

achieve control by harsh

and parsimonious public policy. A

slightly different scenario has be-

nevolent workers appearing as the direct

ancestors of contemporary

advice-givers and social workers who supposedly

use therapeutic jar-

gon to make themselves more secure and

their audiences more

expert-dependent. In this way,

capitalism has purportedly shattered

both individual self-confidence and the

integrity of the family.51

Without disputing the arrogance of

conservatism, either new or

old, we insist that the historical

record is more complex. Certainly,

Protestant charity reformers had their

share of prejudices. The Na-

tional Conference proceedings abound

with unflattering remarks on

immigrants. Many NCCC members were

enthusiastic about eugenics,

a "science" that they would

eventually link to the politics of immi-

grant restriction. However, the

activities of these reformers were prin-

cipally motivated by the foul

institutions and inhumane treatment

that they personally uncovered. And,

more often than not, the poor

conditions were the responsibility of

native-born Protestants like

See also Timothy P. Weber, Living in

the Shadow of the Second Coming: American

Premillennalism, 1875-1975 (New York, 1979), 3-12, 168-69.

51. In addition to Rothman, Discovery

of the Asylum and Conscience and Conven-

ience, see Clifford S. Griffen, Their Brothers' Keepers:

Moral Stewardship in the United

States, 1800-1865 (New Brunswick, N.J., 1960) and Christopher Lasch, Haven

in a

Heartless World: The Family Besieged (New York, 1977).

Origins of Welfare

95

themselves. Albert Byers, though

relatively free of the prejudices of

the day, was not a perfect man. He

regularly denounced political

spoils but used his influence to secure

for his son a position as person-

al secretary to Governor "Calico

Charlie" Foster. He sermonized on

brotherhood and reconciliation, yet

enthusiastically supported the

Grand Army of the Republic which helped

to keep alive the animosi-

ties of the Civil War. Nevertheless,

these imperfections seem less im-

portant than his principal

accomplishment-the reformation of public

welfare through vigilence, compassion

and suggestion. In this en-

deavor, he sought to comfort the

afflicted rather than to cultivate a

client population.52

Albert Byers's experience is meaningful

because he was necessarily

cautious about state power but

relentless in pursuing abuse. The

Ohio Board of State Charities was a weak

organization, even in com-

parison with the other state boards of

the day. Byers could not con-

trol the appointment of trustees and

superintendents of state institu-

tions; nor could he monitor their

expenditures or audit their books.

At the local level, publicity remained

his main weapon.53 Nonethe-

less, the people of Ohio responded to

his fervor. They cleansed their

jails and almshouses and provided

separate homes for dependent

and neglected children. And even though

relapses occurred, we be-

lieve that Byers' accomplishment has a

modern echo. Glenn Tinder

has recently written:

The welfare state is a relatively humble

spiritualization of the public order. It

symbolizes the idea that government

should serve justice and kindness. If

we give up trying to invest our politics

with that modest amount of spiritual

significance-if fiscal responsibility

comes in effect to be our understanding

of the highest good-what will remain in

our public life to command re-

spect?54

In an age that glorifies

self-aggrandizement and inequality, the con-

viction that doing good is its own

reward may serve us well. By

linking us to moderate but active people

of an age gone by, it encour-

ages us to persist until a new

commonwealth philosophy takes shape.

For there is little hope of coping with

the future without recognizing

that our obligations to each other are

rooted in the past.

52. Charles Forster to Roeliff

Brinkerhoff, December 22, 1879, The Papers of Roeliff

Brinkerhoff, OHS; Ohio. Docs., II (1870),

355.

53. Orth, Centralization of

Administration in Ohio, 177; NCCC, Proceedings (1889),

89-97; Ibid., (1893), 33-51

54. New Republic, March 10, 1979,

21-23.