Ohio History Journal

THE WISCONSIN ARCHEOLOGICAL SOCIETY,

STATE FIELD

ASSEMBLY,

July 29-30, 1910.

REPORT BY CHARLES E. BROWN, CURATOR.

Several years ago the Wisconsin

Archaeological Society

adopted the plan of holding summer field

meetings of its mem-

bers in various sections of Wisconsin

which were known to be

rich in prehistoric Indian remains. The

purpose of these annual

gatherings was doubly that of extending

their acquaintance with

the features of the local archaeological

field, and of arousing an

increased popular interest in the

educational value and need of

the scientific exploration and the

preservation of its antiquities.

The first of these state assemblies was

held in the city of

Waukesha, in the year 1906, and was very

successful. In the

following years, similar gatherings of

persons interested in the

state's antiquities were held at

Menasha, at Beloit and at Bara-

boo, each in a different section of the

state, the attendance and

interest increasing from year to year.

The effect of these meet-

ings has been to create an intelligent

interest in Wisconsin's

Indian memorials in every quarter of the

state. It has been the

means of enlisting the cooperation of

the women's clubs, of

county historical societies and other

local associations, and of

cities and villages in protecting and

permanently preserving the

Indian evidences in their respective

neighborhoods. Through a

union of effort of these with the

society, local public museums

and collections have been established,

and archaeological collec-

tions of great value saved to the state.

At the annual meeting of the society

held in the city of

Milwaukee, in March, 1910, an invitation

was presented to

it by its Madison members and by the

State Historical Society,

to hold a two-days field assembly during

the summer in that

charming Wisconsin city. It was urged,

and rightfully, that no

(333)

334 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

more attractive place for a gathering of

persons interested in the

preservation of the state's

archaeological history could be selected.

The picturesque shorelands of the three

beautiful lakes, Men-

dota, Monona and Wingra, in the midst of

which the capital

city of Wisconsin is located abound in

sites of stone age and of

more recent Indian villages, camps and

workshops, and in splen-

did examples of the remarkable

emblematic and other aboriginal

earthworks for which the state is now so

widely known among

American archaeologists. There were

formerly about Lake Men-

dota 30 groups of mounds, about Lake

Monona 12, and about

Lake Wingra 10. Lakes Waubesa and

Kegonsa, which lie at

a short distance from the city also have

about their shores numer-

ous earthen monuments. The total number

of these conspicuous

records of the past existing about the

five lakes of the Madison

chain has been estimated by local

authorities at nearly one thou-

sand. Many of these are still in

existence, and a considerable

number owe their preservation to the

efforts of the local mem-

bers of the society. There are also

still remaining about these

lakes several plots of Indian cornhills,

remnants of trails and

the site of an early fur-trading post.

The courteous invitation thus extended

was accepted by the

Wisconsin Archaeological Society and

shortly thereafter a com-

mittee of Madison members and patrons

was organized to as-.

sume charge of the necessary arrangements

and program for

the meeting.

THE ASSEMBLY.

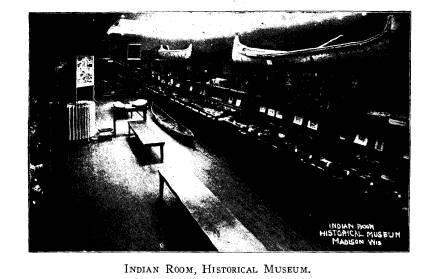

On Friday morning, July 29, the first

day of the assembly,

members of the society and their guests

arriving from many

Wisconsin cities gathered at the

historical museum, in the State

Historical Library building, and were

here received by members

of the Madison committee. Dr. Reuben

Gold Thwaites, superin-

tendent of the State Historical Society

of Wisconsin, delivered

to the visitors a warm address of

welcome. The remainder of

the morning was devoted to a tour of

inspection, under the guid-

ance of members of the State Historical

Society's staff, of the

library and museum, and of the map and

manuscript, illustra-

tion, newspaper and other important

departments of its labors.

|

The Wisconsin Archaeological Society. 335 At 2 P. M., the members and guests of the Wisconsin Archaeological Society to the number of about one hundred assembled at the State street entrance of the State Historical Library for the purpose of participating in a pilgrimage to Mer- rill Springs, for which carriages and 'busses had been provided. The long train of vehicles was lead by one in which were seated Mr. W. W. Warner, local vice-president of the society; Mr. Emilius O. Randall of Columbus, 0., the distinguished guest of the Assembly; Miss Pauline Buell of Madison, and Prof. H. |

|

|

|

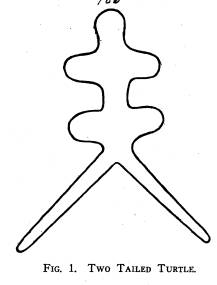

by Agricultural Hall. One of the effigies is that of a large bird with the wings outspread as if in the act of flying toward some distant tree or ridge-top. Its head points toward the south. The other effigy is considered to be intended to represent the turtle, an effigy type common to certain Wisconsin archaelogic areas. This mound is however peculiar among turtle-shaped mounds in possessing two caudal appendages. (See Fig. 1.) It measures about 95 feet in length from the end of its rounded head to the tip of its diverging tails, and about 43 feet in width across the widest portion of its body (across the limbs.) It is represented, |

|

336 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

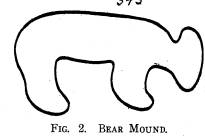

in the act of crawling over the crest of the ridge. Neither of these curious earthworks is over one and a half feet in height at the highest portion of their bodies. These fine mounds, so favorably situated for permanent preservation have recently been marked at the society's request by neat wooden explanatory signs. They are visited each year by hundreds of University students and by visitors from many states. The carriages here left the University grounds and pro- ceeded southward across the city to the vicinity of Henry Vilas park, a picturesque public park on the shore of Lake Wingra. On a small public oval at the head of West Washington street, on the outskirts of this park, is situated a bear-shaped effigy |

|

|

|

with the ceremony of unveiling upon the mound of a descrip- tive bronze tablet. Prof. H. B. Lathrop delivered the presentation address, at the conclusion of which Miss Pauline Buell, a daughter of Mrs. Charles E. Buell of Madison, president of the Wisconsin Feder- ation of Women's Clubs, very gracefully removed the silken flags, and exposed the tablet. It bears the following legend:

BEAR WAH-ZHE-DAH. Common Type of Ancient Indian Effigy Mound. Length 82 Feet. Marked by the Wisconsin Archaeological Society, July 29, 1910. |

The Wisconsin Archaeological

Society. 337

PROFESSOR H. B. LATHROP'S ADDRESS.

The mound of earth at our feet is the

work of hands long quiet,

a memorial the meaning of which by the

time our race came to this

region had been forgotten by the very

aborigines themselves whose

ancestors, it is believed, here built

it. On some summer's day, how

many ages ago we know not, there labored

here a band of dark-skinned

men and women, bearing with them in

sacks and baskets the earth,

toilsomely scooped up with blade-bones,

shells, and bits of wood, of

which this figure is composed. It is not

difficult to imagine the scene

about them as it must have appeared on

that day. The soft homelike

contours of the hills enclosing the lake

below us cannot have greatly

changed; some then as now were darkly

hooded with a close growth of

trees, but on most of them the oaks

stood wide apart in the midst of

an undergrowth of brambles and other

rough bushes, or cast their

shadows in park-like groves on grassy

slopes. The brush was thick, no

doubt, and sheltered bears and deer. The

flocks of water birds on the

lakes in spring and autumn were vast and

noisy. There were no neatly

painted houses ranged in order along

straight white streets, and hollow

trails led from one group to another of

skin tepees near the lake shores,

with great solitudes between them.

In the level meadow below us, and a few

hundred yards to the

southeast, on what was then the edge of

the rushy lake, was one group

of such tents, the village of the

builders of this mound. The oaks still

standing in the park sheltered the

village in its later days. The ground

beneath is full of the signs of the life

of the inhabitants: flint imple-

ments and flakes and potsherds, the

homely and pitiful wealth of the

villagers. Between the two oaks at the

end of the little grove on the

west may yet be found the remnants of

ancient hearthstones, cracked by

fire. The lake near by provided the

inhabitants with the fish and turtles

which formed so large a part of their

food and were so important in

their agriculture. Their corn-field and

their burial ground have not

been discovered, but must have been not

distant. These people must

have led a tolerably settled life; the

region about them was rich in

all the elements of savage prosperity,

and vigorous enemies pressed at

no great distance upon their borders.

Why should they roam far from

so fair a home? On this earth, then grew

the holy sentiments possible

only where mankind have settled

habitations. Here were homes and

love, affection for the lake, the trees,

the hills, for the graves of

ancestors, devotion to the commonweal -

sacred feelings, however crudely

or dimly manifested, however mingled

with savage folly and savage

cruelty.

Dr. Samuel Johnson says, in words which

as Matthew Arnold de-

clares, should be written in letters of

gold over every schoolhouse

Vol. XIX. -22.

338 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

door, "Whatever causes the past,

the distant, or the future to predominate

in our minds over the present, advances

us in the dignity of thinking

beings." Such words will not sound

strange to the members of an

archaeological society. Its very

existence is a call to its members to

escape at times from the confusion and scattering of the spirit

which

come from the welter of daily business,

to turn back to the simple ele-

ments of human nature in this day of

many calling voices, and to

become conscious for a moment of the

long stream of life, unhasting,

unresting, in which our own passes on as

a drop on its way to the

ocean. But it is not the mere outer life

of the past which has an

interest for us. What is the meaning of

this heap of earth? With what

thoughts was it built? Were the minds of

those who made it alien to

ours, or is this mound a little signal

out of the past to let us know

that the thoughts of the past are still

in us? To these questions no

such easy and clear answers can be given

as to those concerned with

the mere externals of the past, and yet

they may be answered if not with

completeness with certainty and with

sufficiency.

Those who peopled the village and built

the mound were Indians

of the Winnebago tribe, members of the

great Siouxan family, and in the

western migration of these peoples from

Virginia a band of the Win-

nebago stopped here on their way near

their brethren, found the land

good, unpeopled or dispeopled as it was,

and here made their home.

Those who settled this village were

members of the Bear Clan; they

had an ideal unity of descent from the

Bear, had the bear spirit in

them, and were all conceived of as kindred.

In course of time, after

their life had become rooted in this

spot, some of them formed this

image of the protecting bear spirit. The

bear was their ancestor, their

guardian, at once the bond of their

community and the object of their

religious devotion. Here this image, endowed with a mystic life,

the

home of the spirits of many ancestors,

not a dead thing or a mere

inanimate figure, watched over their

village, removed from desecrating

companionship and the disturbances of

the village life, but near enough

to exercise a watchful guardianship over

it. To the west lay many

kindred villages of the Bear Clan, often

marked as this one by

effigies. Rude as the mounds are, the

artists who traced them were

not without imagination and delight in

the pictures they drew with so

broad a stroke. The bear effigy-the

black bear no doubt-is nearly

always long-bodied and heavy-footed, but

he is no mere conventional

figure. Sometimes his head is lifted and

he snuffs the air, sometimes it

is thrust forward and at gaze. More

often, as here, the great beast

is stolidly plodding his way through the

underbrush. Each effigy testifies

to the fact that the artist was drawing

sincerely and with delight what

he had seen and knew intimately.

This mound is not in time so ancient as

the Pyramids, but it is in

spirit more primitive and more noble. It

is more noble, since it is not

The Wisconsin Archaeological

Society. 339

the work of drudging slaves, set to

glorify the vanity and selfishness of a

despot, but of a community symbolizing

its bond of communal life

and its religious devotion. It is more

primitive, for it comes from

that childhood of the race when men

believed that human souls

and magical intelligence dwelt in the

beasts. It is more mys-

terious than the Pyramids: we know not

the builders' names, or where

their dust has been laid, though of

their purpose we have some inkling.

Is this symbol of the sacred past and of

the community life alto-

gether strange to us? May we not find a

chord in our hearts to

respond to the sentiment which raised

it?

The tablet we dedicate is the gift to

the Society of a generous

donor who desires his name to be kept

private, and is accepted from

the Society by the City of Madison as a

pledge that this memorial of

a far and dim antiquity will be

preserved intact for the future. The

flag covering the tablet, which Miss

Pauline Buell is now to strip off,

is a symbol of a bond of union higher,

larger, and more ideal than

that of the Bear Clan, but no closer or

more holy than that to its

members. Under that flag should live a

union of spirit higher than a

merely political one. It should be

hospitable to the sacred associations

of all the many peoples in our composite

national life. We cannot

afford to lose a benediction from our

soil; our life will be the richer

for realizing that this was consecrated

ground ages before a white

foot was set upon it.

At the close of this impressive ceremony

the pilgrimage

returned northward again to Lake

Mendota, passing on its way

thither several small groups of

prehistoric mounds on Univer-

sity Heights, and on the State

University grounds, and pro-

ceeded for a distance of several miles

over the winding pleas-

ure drive which here skirts the south

shore of the lake until it

reaches the somewhat noted resort long

known from its clear

springs, as Merrill Springs. Here the party was taken in

charge by Mr. Ernest N. Warner, the

owner of this fine tract

of land.

There are here several extensive groups

of Indian earth-

works. The first to be inspected by the

pilgrims was an inter-

esting group of three bear-shaped

effigies located in a small

grassy enclosure on the lake side of the

driveway. In a wooded

pasture on the opposite side of the road

is an irregularly dis-

posed series of mounds consisting at

this time of three long

tapering linear earthworks, three

conical (burial) mounds of

small size, and two bird

effigies. Most attractive of these earth-

|

340 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

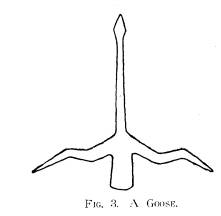

works is a remarkable effigy intended to represent a goose in flight. (See Fig. 3.) Its dimensions, according to a recent sur- vey are: length of body, 50 feet; length of head and neck, 108 feet. Its wings measure about 190 feet from tip to tip. It lies on the slope of a hill with its neck stretching toward to top. Its wings are twice bent, and there is no doubt in the minds of Wis- consin archaeologists concerning its identification. It is one of only a very few examples of its type occurring in the state and its preservation is therefore sought by the society. The largest of the tapering mounds is about 240 feet in length. Passing through this pasture is also a remnant of a well- |

|

|

|

figy, and a line of small conical mounds. A large bird, a bear, and two linear mounds are grouped upon the side and crest of a neighboring hill. After viewing these numerous works of the ancient Indians, the pilgrims returned to Madison.

THE EVENING SESSION. The evening session of the Assembly was held in the lecture hall of the State Historical Museum. The meeting was formally opened at 8 o'clock about 200 persons being in attendance. Dr. Reuben G. Thwaites, the first speaker, delivered an address en- titled, "The Four Lakes Region in Aboriginal Days." He gave an interesting account of the Indian occupation of the region |

The Wisconsin Archaeological

Society. 341

about Madison, describing the locations

of the camps, trail and

fur-trade stations, as described by

early travelers. He was fol-

lowed by Mr. Emilius O. Randall,

secretary of the Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Society,

who protested that he

was not a professional archaeologist,

history being his bent, if

he had any bent at all, and regretted

that his place on the pro-

gram was not filled by Prof. W. C.

Mills, the successful and well-

known curator of the Ohio Society.

Nevertheless Mr. Randall

succeeded in greatly interesting his

audience with his scholarly

address, "The Preservation of

Prehistoric Remains in Ohio,"' in

which he described the work of the Ohio

Society in exploring

and preserving its archaeological

wealth. He told of the preserva-

tion in state park reservations of the

widely celebrated Great

Serpent Mound, and of Fort Ancient. He

also gave an account

of the recent productive explorations of

the Adena mound, the

Baum village site and of other noted

remains and sites, under

state auspices. A state archaeological

atlas is now in prepara-

tion. The archaeological collections in

the society's museum at

Columbus are very extensive and

valuable, and its publications

widely read.

Prof. William Ellery Leonard, Assistant

Professor of Eng-

lish in the University of Wisconsin,

followed with the reading

of a poem prepared especially for the

Assembly. This is printed

here with his kind permission.

PROFESSOR LEONARD'S POEM.

The white man came and builded in these

parts

His house for government, his hall for

arts,

His market-place, his chimneys, and his

roads,

And garden plots before his new abodes,

With fields of grain behind them planted

new,

Then, turned topographer, a map he drew;

And, turned historian, a book did frame;

And gave his high achievement unto fame.

Saying: "To these four ancient

lakes I came,

And saw, and conquered, and with me was

born,

Amid these prairies, and these woods

forlorn,

A corporate life, a commonweal, a place

By me first founded for the human

race."

342 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

We con

his map, his book; for they have worth

Not less than many a civic tale of earth

Of cities builded in the long ago

Where still forever other waters flow.

Yet, if we read the life of states

aright,

Man never yet has built upon a site

Unknown to man before him: ancient Rome,

Long ere 'twas founded, was for man a

home;

The Caesars, landing in the utmost isles

Of Briton, paved the long imperial miles

Between their military towns, among

An earlier folk whom time has left

unsung.

And in still earlier days the Grecian

stock,

(Their gods as yet uncarven in the rock,

Their lyres as yet dumb wood within the

trees

Among the mountains o'er AEgean seas),

Settled to southward in a land even then

Alive with hardihood of sons of men

The rude Pelasgians, rearers of the

stone-

In after eras to be overgrown

With weed and ivy-like at last the

throne

Of marble Zeus himself. Again, they say

That fathoms deep in Egypt's oldest

clay--

Fathoms beneath the sphinx and pyramid

Lie hid-or rather now no longer hid-

Proofs of man's home beside the reeds of

Nile,

Ere ever those Dynasties whose numbered

file

Of uncouth names we learn by rote had

come,

With Isis and Osiris. Hold the thumb

Upon the map of Egypt, and then trace

With the forefinger how another race,

Making its way between the rivers twain

-

Down the low Tigris and Euphrates plain-

Builds that Assyrian kingdom to the sea

Where the mysterious Sumerians be.

In short, wherever a mightier people go

To lands of promise, there's a Jericho

Before whose elder walls their trumpets

first must blow.

So here: our sires who felled the forest

trees

Received from dark-skinned aborigines

The lamp of life. And though we well may

say,

"That lamp burns brighter in our

hands today,"

We well may add, in reverence for the

great

Primordial law that binds all life to

fate,

"That lamp of life, though wild and

wan its flame,

Still burned in other hands before we

came."

The Wisconsin Archaeological

Society. 343

Here was a desert only in the name-

And from the view-point of that narrow

pride

Which names a strange thing chiefly to

deride.

Here was no desert: every hill and vale,

Each lake and watercourse, each grove

and trail,

Was know to thousands who, like me and

you,

Watched the great cloud-drifts in the

central blue

And sun and moon and stars; like you and

me,

Laughed, wept and danced and planned the

thing to be.

The whole wide landscape, rock, and

spring, and plain,

Lay long since chartered in the human

brain,

And had its names, its legendary lore,

Which countless children from their

fathers bore

Down to their children's children.

So man's mind

Even then was more than nature, brute

and blind,

By virtue of that element of thought

Through which our own devices have been

wrought.

Here in the villages by wood and shore,

With infants toddling through the wigwam

door,

Were arts and crafts, in simpler form,

but still

The same we practice in the shop and

mill--

Here bowl and pitcher, moccasin and

belt,

Mattock and spade and club and pipe and

celt,

Fashioned not only for the work to do,

But often with many a tracery and hue,

To please that sense of something in the

eye

We now call beauty-though we know not

why.

And here was seed-time in the self-same

loam

We plow today; here too was harvest

home.

Here were assemblies of the counsellors;

Here unsung heroes led the hosts to wars.

Here gathered at seasons family and clan

To serve the god from whence its line

began,

Or bury its chieftains; for the Gods,

the dead,

Were unto them, as us, yet more than

bread,

Yet more than drink and raiment, as it

seems,

And they, as we do, lived in part by

dreams.

And the high places round these lakes

attest

The age-old mysteries of the human

breast.

Thus, if you'll fill the picture out

I've drawn,

Touch it with color and atmosphere of

dawn,

You'll see an immemorial world of man,

Perhaps but portion of a larger plan

344 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Of which we too may but a portion be

In that sum-total solidarity

Of human beings spread across the earth

In generations, birth succeeding birth-

The living who raise the citadels we

know,

The dead whose bones earth bosomed long

ago.

And this good company that meets today

Proves the large truth of what I've

sought to say;

For why should we, whose daily

tasks alone

So press upon us that we scarcely own

The present hour, still take on us to gaze

Back on the parted, the forgotten days;

Why should we leave the quest for daily

bread,

To quest for relics of the savage dead;

Why should we leave our figuring for

gold

To figure out a vanished world of old?-

Except that thus in human nature lurks,

Except that thus in human nature works

Some sense of common comradry and kin

With human life, wherever it has been,

And in the use of such a sense we find

Enlargement for our human heart and

mind.

Dr. Carl Russell Fish, professor of

American history in the

University of Wisconsin, furnished the

final number on the pro-

gram. His very instructive address

entitled, "The Relation of

Archaeology to History, is here

presented.

ADDRESS OF PROFESSOR FISH.

The derivation of the word archaeology

gives little idea of its

present use. "The study of

antiquity" is at once too broad in scope

and too limited in time, for the

followers of a dozen other "ologies" are

studying antiquity, while the

archaeologist does not confine himself to

that period. The definition of the word

in the new English dictionary

corrects the first of these errors, but

emphasizes the second, for it

describes it as: "The scientific

study of remains and monuments of the

prehistoric period." This obviously

will not bear examination, as the

bulk of archeological endeavor falls

within the period which is considered

historical, and I cannot conceive any

period prehistoric, about which

archeology, or any other science, can

give us information. Actually, time

has nothing whatever to do with the

limitations of archaeology, and to

think of it as leaving off where history

begins, is to misconceive them

The Wisconsin Archaeological

Society. 345

both. The only proper limitation upon

archaeology lies in its subject

matter, and I conceive that it cannot be

further defined than as: "The

scientific study of human remains and

monuments."

In considering the relations of the

science to history, I do not

wish to enter into any war of words as

to claims of "sociology", and

"anthropology" and

"history" to be the inclusive word, covering the

totality of man's past, but simply to

use history as it is generally

understood at present and as its

professors act upon it. Certainly we

are no longer at the stage where history

could be defined as "Past

Politics," and it is equally

certain that there are fields of human activity

which are not actually treated in any

adequate way by the historian.

The relations of the two do not depend

on the definition of history,

but the more broadly it is interpreted,

the more intimate their relationship

becomes. The sources of history are

three-fold, written, spoken, and

that which is neither written nor

spoken.

To preserve and prepare the first, is

the business of the philologist,

the archivist, the paleographer, the

editor, and experts in a dozen sub-

sidiary sciences. The historian devotes

so much the larger part of

his time to this class of material, that

the period for which written

materials exists is sometimes spoken of

as the historical period, and

the erroneous ideas of archaeology which

I have quoted, become common.

Least important of the three, is the

spoken or traditional, though if

we include all the material that was

passed down for centuries by word

of mouth before being reduced to

writing, such as the Homeric poems or

the Norse sagas, it includes some of the

most interesting things we

know of the past. In American history,

such material deals chiefly

with the Indian civilizations, and its

collection is carried on chiefly

by the anthropologists. In addition,

nearly every family preserves a mass

of oral traditions running back for

about a hundred years; and there

is a small body of general information,

bounded by about the same

limit, which has never yet been put into

permanent form. The win-

nowing of this material to secure

occasional kernels of historic truth

that it yields is as yet a neglected

function.

The material that is neither written nor

oral falls to the geologist and

the archaeologist. Between these two

sciences there is striking simi-

larity, but their boundaries are clear;

the geologist deals with natural

phenomena, the archaeologist with that

which is human, and which may,

for convenience, be called monumental.

The first duty of the archaeolo-

gist is to discover such material and to

verify it, the next is to secure

its preservation, preferably its actual

tangible preservation, but if that

is not possible, by description. Then

comes the task of studying it,

classifying and arranging it, and making

it ready for use. At this point

the function of the archaeologist

ceases, and the duty of the historian

begins; to interpret it, and to bring it

into harmony with the recognized

body of information regarding the past.

It is not necessary that different

346 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

individuals in every case do these

different things. We must not press

specialization too far. Nearly every

historian should be something of an

archaeologist, and every archeologist

should be something of an his-

torian. When the archaeologist ceases

from the preparation of his

material, and begins the reconstruction

of the past, he commences to

act as an historian; he has to call up a

new range of equipment, a new

set of qualifications.

The fields in which the services of

archaeology are most appreciated

are those to which written and oral

records do not reach. Its con-

tributions in pressing back the

frontiers of knowledge are incalculable,

and are growing increasingly so with

every passing year. To say nothing

of what it has told us of the

civilizations of Egypt and Assyria, it has

given to history within the last few

years the whole great empire of the

Hittites. We have learned more of

Mycenaean civilization from archae-

ology than from Homer. Practically all

we know of the Romanization

of Britain is from such sources, and

that process, not long ago regarded

almost as a myth, is now a well

articulated bit of history. In America,

within the last thirty-five years, by

the joint work of the archaeologist and

the anthropologist, many of the points

long disputed concerning the

Indians have been set at rest, more

knowledge of them has been recovered

than was ever before supposed possible,

and new questions have been

raised which invite renewed activity.

From all over the world, moreover,

remains of the past, amount-

ing to many times those now known, call

for investigation. It is safe to

say that within the next fifty years

more sensational discoveries will

be made by following material, than

written, records.

It is not, however, only in the periods

void of written sources

that archaeology can perform its

services. It is in the period of classical

antiquity that we find the combination

happiest. There, indeed, it is

difficult to find an historian who does

not lay archaeology under tribute,

or an archaeologist who is not lively to

the historical bearing of his work.

When we come to the medieval period the

situation is less ideal, the his-

torian tends to pay less attention to

monuments, and the archaeologist to

become an antiquarian, intent upon

minutia, and losing sight of his

ultimate duty. In the modern period, the

historian, self-satisfied with the

richness of his written sources, ignores

all others, and the archaeologist,

always with a little love for the

unusual and for the rust of time,

considers himself absolved from further

work.

As one working in this last period, I

wish to call the attention

of American archaeologists to some

possibilities that it offers. Abundant

as are our resources they do not tell

the whole story of the last couple of

centuries even in America, and we have

monuments which are worthy

of preservation and which can add to our

knowledge of our American

ancestors, as well as of our Indian

predecessors. Even in Wisconsin

something may be obtained from such

sources.

The Wisconsin Archaeological

Society. 347

The most interesting of our monumental

remains are, of course,

the architectural. Everybody is familiar

with the log cabin, though

something might yet be gathered as to

the sites selected for them, and

minor differences in construction. Less

familiar is the cropping out of

the porch in front, the spreading of the

ell behind, and the two lean-to

wings, then the sheathing with

clap-boards, the evolution of the porch

posts into Greek columns, and the clothing

of the whole with white paint,

all representing stages in the

prosperity of the occupants. In nearly every

older Wisconsin township may be found

buildings representing every

one of these stages, the older ones

indicating poor land or unthrifty

occupants and being generally remote

from the township center, or

else serving as minor farm buildings

behind more pretentious frame or

brick structures. In the same way the

stump fence, the snake fence and

the wire fence, denote advance or the

retardation of progress. Other

studies of economic value may be made

from the use of different kinds

of building materials. The early use of

local stone is one of the features

of Madison, its subsequent disuse was

due not so much to the diffi-

culty of quarrying as to the decreased

cost of transportation making other

materials cheaper, and was coincident

with the arrival of the railroads.

Very interesting material could be

obtained from the abandoned river

towns, still preserving the appearance

of fifty years ago, and furnishing

us with genuine American ruins.

On the whole the primitive log cabins

were necessarily much alike,

but when the log came to be superseded

by more flexible material,

the settler's first idea was to

reproduce the home or the ideal of his

childhood, and the house tends to reveal

the nationality of its builder.

Just about Madison there are farm houses

as unmistakably of New Eng-

land as if found in the "Old

Colony," and others as distinctly of Penn-

sylvania or the South. I am told of a

settlement of Cornishmen,

which they have made absolutely

characteristic, and even the automobilist

can often distinguish the first

Wisconsin home of the German, the

Englishman or the Dutchman. Where have

our carpenters, our masons

and finishers come from, and what tricks

of the trade have each

contributed ?

Such studies reveal something also of

the soul of the people. Not

so much in America, to be sure, as in

Europe, where national and

individual aspirations find as legitimate

expression in architecture, as

in poetry; and less here in the West,

which copied its fashions, than

in the East, which imported them. Still

we have a few of the Greek

porticoed buildings which were in part a

reflection of the influence of the

first French Republic and in part

represented the admiration of the

Jeffersonian democracy for the republics

of Greece; but that style

almost passed away before Wisconsin was

settled. We have a number of

the composite porticoed and domed

buildings which succeeded and

represented perhaps the kinship between

the cruder democracy of Jackson

348 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

and that of Rome. We have many buildings both public and private,

some extremely beautiful, which reflect

the days in the middle of the

nineteenth century when the best minds

in America drew inspiration

from the Italy of the Renaissance, when

Story and Crawford, and

Hawthorne and Margaret Fuller lived and

worked in Rome. The

succeeding period when the French

mansard stands for the dominating

influence on things artistic, or rather

inartistic, of the Second Empire,

is everywhere illustrated; while the

revival of English influence, in

the Queen Anne; the beginning of general

interest in American history,

in the colonial; the influence of the war

with Spain; in the square

cement; and many other waves of thought

and interest, can be pointed out

in almost any town. A careful study of

its architecture will nearly

always reveal the approximate date of

foundation, the periods of pros-

perity and depression, the origin of the

inhabitants, and many other

facts of real importance.

I have spoken so far of the contribution

of archaeology to the

science of history. Fully as great are

its possibilities along the lines of

popularization and illustration. The

work of neither archaeology nor

history can go on without popular

support, and the local appeal is one of

the strongest that can be made. Not

every town has an interesting

history, but almost every one, however

ugly, can be made historically

interesting to its inhabitants, if its

streets can be made to tell its history,

and by reflection something of the

history of the country, which may

be done merely by opening their eyes to

their chirography. It should be

part of the hope of the local archaeologist

to make his neighbors and his

neighbor's children see history in

everything about them, and if this is

accomplished we may hope gradually to

arouse a deeper and more

scientific interest, and a willingness

to encourage that research into the

whole past, in which historian and

archaeologist are jointly interested.

On a recent visit to Lake Koshkonong I

found my interest very

much stimulated by the admirable map and

plates illustrating the Indian

life about its shores, and it has

occurred to me that one extremely

valuable way of arousing general

interest and of arranging our archae-

ological data, would be in a series of

such minute maps. For instance the

first in the series would give purely

the physical features, the next, on

the same scale, would add our Indian

data-mounds, village sites, culti-

vated fields, arrow factories and

battle-fields, trails and any other indi-

cations that might appear--then one on

the entrance of the white men,

with trading posts, garrisons, first

settlements and roads, the next

would begin with the school house and

end with the railroad, and one

or two more would complete the set. Such

studies of the material

changes of a locality, would not form an

embellishment, but the basis

of its history.

Another work might be undertaken through

the local high school.

The pupils might be encouraged to take

photographs of houses, fences,

The Wisconsin Archaeological

Society. 349

bridges and other objects, interesting

for the reasons I have pointed out,

as well as all objects of aboriginal

interest. These should always be dated

and the place where they were taken

noted. In fact, a map should be

used, and by numbers or some such device

the pictures localized. These

photographs properly classified and

arranged would give such a picture

of the whole life of the community in

terms of tangible remains as

could not fail to interest its

inhabitants as well as serve the student.

In the newer portions of the state,

particularly in the north it would be

possible to take pictures of the first

clearing, and then file them away

and a few years later take another

picture of the farmstead with its

improvements and so on until it reached

a condition of stability. Thus

to project into the future the work of a

science whose name suggests

antiquity, may seem fantastic, but even

the future will ultimately become

antiquity. We have still in Wisconsin

some remnants of a frontier stage

of civilization which is passing and

cannot be reproduced, and to provide

materials to express it to the future

cannot be held superfluous. If we

imagine the joy that it would give to us

to find a photograph of the

site of Rome before that city was built,

of one of the great Indian villages

of Wisconsin before the coming of the

white man, we can form a con-

ception of the value of such an ordered

and scientific collection as I have

suggested to the future student of the

civilization of our own day.

At the conclusion of the program an

informal reception was

tendered the guests by the Madison

members of the Wisconsin

Archaeological Society, light

refreshments being served by the

ladies of the historical library staff.

The entire museum was

thrown open to the visitors, who spent

the remainder of the

evening in inspecting its historical and

anthropological collections.

The historical museum had its beginning

in 1854, and has main-

tained a persistent and progressive

growth since that date. It

occupies the entire upper floor of the

State Historical Library

building, and has eight exhibition

halls. Its chief aim is popular

education along the lines of Wisconsin

history. It takes promin-

ent rank as an educational institution,

and entertains from 60,000

to 80,000 visitors each year.

In addition to its regular collections

the museum had pre-

pared for the occasion of the Assembly a

series of special ex-

hibits. These included the original

surveys and maps, and corre-

spondence relating to Wisconsin

antiquities of Dr. Increase A.

Lapham, the state's distinguished

pioneer antiquarian, and of his

|

350 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

associates, Dr. P. R. Hoy, Moses Strong, Dr. S. P Lathrop, W. H. Canfield and others, these occupying several large cases; a screen exhibit illustrating the archaeological features of the Four Lakes region; a collection of Belgian "eoliths," loaned by Dr. Frederick Starr; a collection of photogravure reproductions of the E. S. Curtis photographs of North American Indians; a col- lection of chipped flint and pecked stone implements from Japan, |

|

|

|

and a number of smaller exhibits. All of these were greatly appreciated by the visitors.

THE SECOND DAY'S PILGRIMAGE. On the morning of July 30, the second day of the Assembly, a body of about 150 members and guests of the society gathered at the Wisconsin University boat-house for a pilgrimage to points of archaeological and historical interest on the north shore of Lake Mendota. They were conveyed across the lake to the State Hospital grounds at Mendota by a fleet of launches. Arriving on |

|

The Wisconsin Archaeological Society. 351

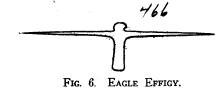

the grounds they were taken in charge by Dr. Charles Gorst, the superintendent, and Mrs. Gorst, and permitted to inspect the buildings of this model institution under their guidance. There are upon this beautiful tract of state property, many acres in extent, several particularly interesting groups of Indian earthworks, the most important of which is permanently pre- served upon the large and well-cared for lawn extending from the lake bank to the main hospital, a distance of about a quarter of a mile. Among the effigies in this series are three bird-shaped mounds, all of immense proportions, and others representing the deer, squirrel, bear and panther. Most interesting of these is the large so-called "eagle" effigy. (See Fig. 6.) This remarkable |

|

|

|

tion by the primitive inhabitants of this site must have cost an immense amount of labor. Comfortably seated upon the body of this huge mound be- neath the shade of the majestic elm and basswood trees which surround it, the archaeological pilgrims listened to a brief address by Mr. Arlow B. Stout, chairman of the society's Research Com- mittee, in which he explained what was being done to complete surveys and explorations of the Indian remains about Madison. Rev. Mr. F. A. Gilmore then delivered a very instructive address at the close of which he presented to the state, in the name of the society and of its donor, Mr. James M. Pyott, a prominent member, the fine metal tablet provided for the marking of this mound. Miss Genevieve Gorst, a daughter of Dr. and Mrs. Charles Gorst, removed the national colors and exposed to view the tablet which had been mounted upon a small monument placed upon the body of the mound. It bears the following inscription: |

352 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

EAGLE EFFIGY.

Largest Indian mound of its type in

Wisconsin.

Body 131 feet. Wing spread 624 feet.

Marked by the Wisconsin Archaeological

Society,

July 30, 1910.

ADDRESS OF REV. F. A. GILMORE.

Archaeology and theology have sometimes

been grouped together,

since both are said to deal with

subjects of no interest to modern men.

As a theologian I should be glad to

refute this idea: but though I know

you are all eager to hear me discourse

on theology, you must bear with

me if I disappoint you. Suffice it to

say that theology or the attempt to

answer the ultimate questions which life

puts to us, can never become

obsolete.

Archaeology is by no means a useless

branch of learning. It is, to

be sure, the study of things that lie

far behind us, "in the dark back-

ward and abysm of time"; but these

things have to do with the life.

of humanity. These mounds are the

records and symbols of human

thought. Hence we think that every

cultivated man should know some-

thing about them. For what is culture?

It is the knowledge of what

the race has thought and done. Much is

claimed in these days for prac-

tical studies such as farming,

engineering and the like. But these can

never replace such subjects as language,

history, philosophy, art and

archaeology for it is these that give us

insight into our vast human

inheritance. By them we enter the life

of the race. Archaeological

studies may not butter anyone's bread

(unless it be Secretary Brown's)

they do give us the key to the evolution

of man.

Effigy mounds are found in several parts

of the United States-by

far the greater number are in Wisconsin.

Here was an epidemic of

mound building. In the early days they

were thought to have been built

by the ten "Lost Tribes of

Israel"; or by a prehistoric race far superior

to the Indians in civilization; or by

the Aztecs before they migrated

to Mexico. The "consensus of the

competent" now pronounces them

to have been the work of the Winnebago

Indians, probably a few cen-

turies before the landing of Columbus.

It is a curious fact that the French

missionaries and fur traders

who were in Wisconsin as early as

1634-only fourteen years after the

settlement of Plymouth, Massachusetts-

make no mention of the mounds.

The Indians of that time did not make

effigy mounds and seem to have

lost all knowledge of them. They did not

reverence them for they built

their villages, planted their corn

fields and buried their dead in them.

The Wisconsin Archaeological

Society. 353

These mounds belong to a class of

venerated objects called Totems.

Totem is a word of Wisconsin origin and

comes from the Chippewa

language. It has now passed into general

use in the terminology of sci-

ence. It means, "my protector"

or "my familiar patron". Totemism is

found among primitive people as far

apart as Australia and Africa,

India and aboriginal America. A Totem

may be a vegetable or an animal,

a war club or other object, and even the

elements like the rain or sun-

shine. These objects were tattooed or

burned on the body, scratched on

the walls of caves, painted on the

wigwam, the canoe or paddle, cut upon

poles and erected in front of the

dwelling. With certain Indian tribes

the Totem was formed in effigy, notably

by the Siouxan tribes. Some-

times they were formed of stones laid

out in the outline of a gigantic

animal or bird. Among the Winnebagoes, a

branch of the Siouxan stock,

it was the fashion to form them out of

the earth.

There are individual Totems, sex Totems,

and Clan Totems. These

mounds are of the latter class. A clan

Totem was some bird, animal or

fish or weapon regarded as the dwelling

place of a spirit or divinity.

This divinity was the ancestor of all

the members of the clan. The clan

members were thus bound together in a

common blood relationship.

They regarded each other as Brothers,

and looked to the deity repre-

sented by the Totem, for protection and

help. Marriage was generally

forbidden within the clan. Children in

some tribes were of the father's

Totem; more often of the mother's. When

a clan grew in numbers it

might divide, the new formed clan taking

a Totem allied to the original

one. Thus the turtle clan among the

Iroquois comprised the mud turtle

clan, the snapping turtle clan, the

yellow turtle clan, etc. This group of

clans is sometimes called a phratry. A

large Indian tribe would thus be

formed of several phratries and these of

several clans.

The clan was the unit of the tribal

life, on the march and in the

arrangement of the village. When the

Omahas marched a certain clan

order was observed, and when they camped

the twelve clans took pre-

scribed places in the circle like the

figures on a clock dial. We might

think of the Totem as the Stem and the

religious customs and the

social laws of the tribe, as the

branches growing out of it. Or using

another figure we may call the Totem

idea the tissue of the common

tie which made a unit of the clan or tribe.

Religious customs connected

with the Totem.

The Totem figured in the ceremonies at

the birth of children.

In the deer clan of the Omahas the

infant was painted with spots to

imitate a fawn. Young lads had their

hair cut out to imitate the horns of

a deer, the legs and tail of a turtle or

other Totem. At puberity there

was an important ceremony initiating the

youth into the clan membership.

Members of the clan dressed to imitate

the Totem, danced and mimicked

the actions and voice of the animal.

Sometimes the novice was clothed

Vol. XIX. -

23.

354 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

in the animal's skin and laid in a

grave; the name of the Totem was

then shouted aloud. At this name the

youth arose from the grave,

signifying his new life as a clan

member, the passing from youth to the

higher estate of manhood; or perhaps

that the Totem had power to

give him life beyond the grave. In some

tribes there seems to have

been a certain formula of words and

gestures as a part of this ceremony.

This may have been a secret sign by

means of which a person could

pass from clan to clan and find

entertainment and fellowship, even where

the language was different. In

Australia, by means of this Totem

formula, a man might travel for a

thousand miles and find friends of the

same Totem.

Death ceremonies. The buffalo clan of

the Omahas wrapped the

dying man in a buffalo robe and said,

"You are now going to your

ancestors the buffaloes. Be

strong." We find the burial mounds placed

close to the Totem effigies as if for

protection.

The custom of taboo spring out of

veneration for the Totem.

The red maize clan of the Omahas will

not eat of that grain. It would

give them sore mouths they say. Members

of the deer clan in the same

tribe will not use the skin of a deer

for robes or moccasins nor its oil

for the hair, but may eat the meat for

food. The Totem animal was

sometimes kept in captivity and

carefully fed. In Java the red dog clan

had a red dog in each family and no one

might strike it with impunity.

A dead Totem was properly buried. In

Samoa a man of the owl clan

finding a dead owl will mourn for it as

for a human being. This does

not mean that the Totem is dead; he

lives in all the other owls. This

is a characteristic of Totemism, to

reverence the species; whereas

reverence for a single animal or object

is a characteristic or Fetichism.

When the Totem was to be killed for food

apologies were made to it.

Or flattery would be used, as when the

fisherman before setting his lines

to catch the Totem fish would call to

them, "Ho! you fish, you are

all chiefs." The Totem helped in

hunting; also in sickness. The medi-

cine man imitated the motions and voice

of the Totem to drive out

the sickness.

Omens came from the Totem. An eagle

flying toward a war party

was a sign to go back; if it flew with

them it was a sign to go on.

A curious ceremony took place among the

Omahas. A turtle was deco-

rated with strips of red cloth tied to

its head, legs and tail, tobacco was

placed on its back and it was headed

toward the south. This ceremony

was intended to drive away the fog! The

logical connection between

cause and effect would puzzle a Whately

or Jevons to discover; but it was

doubtless there to the Indian mind.

When running foot races the Indians

often carried an image of the

Totem on the breast or back. In signing

treaties the Totem was affixed

as a signature,

The Wisconsin Archaeological

Society. 355

Before drawing the conclusion from these

facts I wish to say a

word about the art of these mounds and

their date. The Indian builders

certainly had an artistic sense. We find

that land animals such as the

bear, deer, panther, etc., are always

formed with the legs on one side,

and with rare exceptions the legs are

never separated. Amphibious

creatures, the turtle, lizard, etc.,

have the legs spread out, two on each

side. Birds have the wings wide spread

or curving and the feet do

not appear. The attitudes of the animals

is not the same for all. There

is artistic variety. Sometimes they are

standing still, again they are

prowling. In several localities in this

state two panthers are built

close together and their attitudes shows

them in combat. In other

places they are guarding caches of food

or the village enclosure.

We have no clear light as to the date of

these works. They were

erected when the land features were

about the same as now. About the

same distribution of forest and prairie,

level of soil and depth of

streams and lakes. There were the same

animals. Neither extinct nor

domestic animals are represented in the

effigies. After the days of the

mastodon, and after the present

topographical features were established,

with the same fauna and flora as found

by the white men at the time

of their first contact with the Indians,

but before the white men came

these mounds were built.

Sometimes we find several similar

effigies in the same locality. This

may mark some favorite gathering place

of the aborigines, as at Lake

Koshkonong where several clans having

the same Totem gathered for

fishing. Again they are found in maple

groves where the Indians came

for the sugar. Madison and the region of

the four lakes, called

Tycoperah by the natives, was a favorite

locality. Here are five eagle

mounds, several bears, panthers,

squirrels, etc. We may imagine the

region to have been a sort of capitol in

prehistoric days--giving laws

and knowledge to those who stayed at

home as it does today.

The old Greek mathematician quite

confounded his contemporaries

when he measured the distance from the

shore to a ship in the offing

without leaving the land. In somewhat

similar wise we can pretty closely

approximate the distance from us of the

mound builders and get a fairly

correct idea of the folk themselves. By

the help which we get from

archaeology and the study of Indian life

since the advent of the whites,

and particularly the institution of

Totemism, we can reconstruct that

vanished life.

This region was occupied by a

homogeneous people, probably the

Winnebagoes, its various clans and clan

groups spread from the Wis-

consin, river to the Illinois line, and

from Lake Michigan to the Mis-

sissippi. They were not harried and

driven by their enemies, but

lived in comparative peace. The clans

moved about, in Spring settling

in some sugar grove, in Summer moving to

a fishing place, in Winter

remaining at the regular villages. At

all these places they made their

356 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Totems in the soil. Certain spots, as at

Aztalan and Lake Horicon

were the seats of large permanent

settlements with earth walls and

raised earth platforms for the council

house or medicine tent. They

had corn fields and garden beds but no

domestic animals. Their mode

of life, clothing, houses, implements,

their religious ideas were those

of the Indian at the time of Columbus.

They belonged to the stone

age but had passed out of the lowest

stage of barbarism to the some-

what settled life of communities with

agriculture. Quite certainly the

mounds where we now stand marked the

site of a community. Secretary

Brown with Mr. August Roden and myself

dug into a refuse heap a few

rods west of this spot, where we found

clam shells, bones and pieces of

pottery. These effigies, the buffalo,

deer, squirrel and eagle were the

clan Totems of that viilage. Here were

held the clan dances and cere-

monies; here the youth were initiated

into clan membership, and given

the secret words which assured him a

welcome in other clans with the

same Totem. Here the young

"eagle" wooed the maiden of the deer

clan, for he might not marry one of his

own Totem.

This eagle mound is a clan Totem of that

village. A populous clan

it must have been to erect so huge a

work. The eagle has always

been admired for its strength and

courage. Wheeling far aloft or

resting on motionless wing it is an

impressive sight. And when, seeing

the fish hawk rise with its prey it

pursues it, and falling like a thunderbolt

snatches the dropped fish ere it touches

the water, it suggests the

supernatural even to a modern mind.

The eagle has been widely used as an

emblem. It was perched on

the Roman standards. It is the national

emblem of Russia, Prussia,

Austria and the United States. When in

1782 Congress chose the eagle

to be our national emblem it did not

realize that it had been used in the

same way in this country centuries

before. Wisconsin had a celebrated

eagle carried to the front in the civil war

by one of its regiments,

and known to every school child as

"Old Abe, the war eagle of Wis-

consin". May we not believe that

"Old Abe, captured in the forests of

Wisconsin was a lineal descendant of

that majestic, pristine bird whose

image is outstretched here at our feet?

There are five eagle mounds in the

vicinity of Madison; others are

found in different places in the state.

One at Mauston has a wing

spread of 325 feet; one in Sauk county

spreads 400 feet; one at the

southeast end of Lake Monona reaches 450

feet. This one before us is the

mammoth of them all; its wings extend

624 feet from tip to tip and is the

largest in the state, as well, I

believe, as in the world.

John Fiske has reminded us that in the

American Indian as he

was at the coming of the Europeans, we

have the man of the stone

age. That period of human development

which preceded civilization

in Europe, and which is only known by

its scattered vestiges in caves

and river beds-was greatly prolonged on

this continent. Indian cul-

The Wisconsin Archaeological

Society. 357

ture, Indian social life, religion,

mythology, art, etc., reproduce and

preserve for us the features of that

savage state which lies so far back

in Europe-beyond all written history. It

was a culture like that of the

mound builders out of which arose the

civilization of Greece and Rome.

This is the great value of archaeology

and fully justifies the interest we

take in Indian remains and our efforts

to preserve them. A large lizard

mound which once stood on the capital

park has been destroyed. This

was an "unpardonable sin", and

could only happen because of the gen-

eral ignorance. It proves how,

"Evil is wrought by want of thought

As well as want of heart."

It is told of a teacher from another

state, that seeing the mounds

where we now stand he took them to be

bunkers on a golf course!

Doubtless he imagined them to be some of

the improvements to the

hospital made under the superintendency

of Dr. Gorst.

We take great satisfaction in unveiling

this tablet marking the

hugest mound of its type in existence.

This tablet is presented by Mr.

James M. Pyott of Chicago, who has been

a member of the Wisconsin

Archaeological Society for many years

and has always taken a deep

interest in its work.

At noon a fine picnic dinner was served

by a committee of

the Madison ladies upon tables placed

beneath the trees upon

the lawn. After its conclusion, Mr.

Stout conducted the visi-

tors to the various mounds upon the

grounds and giving in-

formation as to their character and

dimensions. At 1:30 P. M.,

the launches were again boarded and a

trip of several miles

across the water made to Morris Park, a

well-known beauty

spot upon the north shore of the lake.

At this place ample time

was given to view under the guidance of

the Messrs. A. B.

Stout and Prof. Albert S. Flint, a

considerable number of

burial, linear and effigy mounds. The

latter include a single

bird effigy and a number of large

effigies of the panther type.

The conical mounds located here include

some of the most

prominent and best preserved about the

Madison Lakes,

A plot of Indian cornhills located at

the southeast cor-

ner of the property greatly interested

the pilgrims. Morris Park

has recently been laid out in summer

resort lots by a Madison

real estate dealer. The Society is

making a determined effort

to save the mounds.

|

358 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

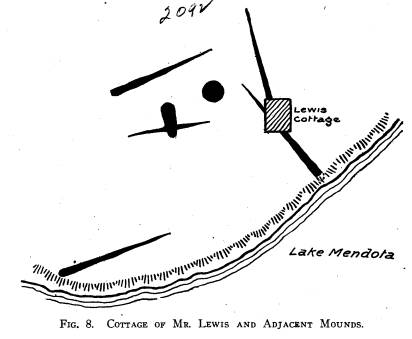

A return was then made to the launches and the pilgrims conveyed along the shore of the lake to West Point, situated at its northwest corner. Arriving at this attractive spot, they were welcomed by Hon. Henry M. Lewis, whose summer home is located here. His cottage stands in the midst of a series of earthworks which consists of four tapering linear mounds, a small burial mound and a bird effigy. Two of the tapering mounds extend beneath the cottage. Judge Lewis, in his informal address, |

|

|

|

gave an interesting account of the Indian history of the region immediately surrounding his home, describing the early Winne- bago village, and a council held at the neighboring Fox Bluff with them by Maj. Henry Dodge, on May 25, 1832, for the purpose of urging them not to participate in the then impend- ing Black Hawk war. Miss Louise Kellogg entertained the guests with a history of the fur-trading post located in early days near West Point. President Arthur Wenz, being introduced by Secretary Charles |

|

The Wisconsin Archaeological Society. 359 E. Brown, briefly explained the aims and work of the Wis- consin Archaeological Society. He expressed the grateful ap- preciation of the organization to the committee of local archae- ologists and their ladies, and to all others who had contributed to the great success of the Madison meeting. At the request of the pilgrims, Dr. Frederick Starr of the University of Chicago, was then called upon and responded with a stirring address. He explained the educational and scientific value of |

|

|

|

Wisconsin's ancient animal-shaped and other prehistoric Indian monuments, and deplored their destruction through the opera- tions of money-grabbing "land sharks" and other agencies. Wis- consin citizens had cause, he stated, to be justly proud of the work of the state archaeological society in creating a state-wide interest in their protection and preservation. He discussed at length the authorship and totemic significance of the emblematic mounds. |