Ohio History Journal

|

"Mr. Republican" Turns "SOCIALIST" |

|

|

|

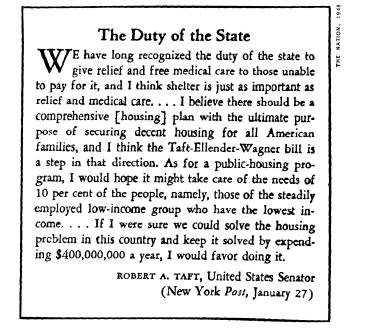

ROBERT A. TAFT and Public Housing by RICHARD O. DAVIES To the great majority of his contemporaries, Senator Robert A. Taft em- bodied the traditional values of self-help, private enterprise, and dislike for governmental welfare programs. Most Americans believed that Taft had as his major purpose the root and branch eradication of all New Deal welfare and regulatory programs. His adamant opposition to the proliferation of such governmental activities supposedly led to a frontal assault upon President Harry S. Truman's "Fair Deal." A "basic hatred of the New Deal" motivated Taft's opposition to Truman's domestic poli- cies, explained the New Republic.1 In Taft, liberal William V. Shannon found the personification of "conservative orthodoxy."2 As a senator, an- other liberal journal editorialized at the time of his death in 1953, Taft had been "the nation's most relentless enemy of the New and Fair Deal Administrations."3 This image has generally remained until the present. One of the best historical surveys of the post-war period depicts Taft as the leader against all reforms of a welfare nature,4 and many leading college texts do little or nothing to correct this interpretation.5 Elmo Roper, in 1957, wrote that NOTES ARE ON PAGES 196-197 |

136 OHIO HISTORY

Taft, more than any other of his

contemporaries, opposed the encroach-

ment of the federal government into the

area of private enterprise be-

cause "he continued to see the

world wholly in individual terms and to

believe that the protections the New

Deal was offering against economic

insecurity were standing in the way of

the free growth of strong, self-

reliant individuals and thriving

business enterprise." Cogently summar-

izing the standard view of Taft, Roper

observed: "He identified himself

with the belief that the innovations of

the Democrats in the national and

international field were causes and not

results of the new problems that

beset the country. By the end of the war

he had become a strong rally-

ing point for those who believed the

national government was headed

in the wrong direction."6

Although this general interpretation is

correct in many instances, it

nonetheless needs revision. Taft may

have been one of Harry S. Truman's

major political critics, and he may have

played an important role in pre-

venting the adoption of the bulk of the

Fair Deal, but in the important

area of housing Taft was a leading supporter

and defender of the Tru-

man program. During the first four years

of the Truman administration,

housing policy figured prominently in

national politics. An acute hous-

ing shortage, which reached almost

5,000,000 units by mid-1946, thrust

housing into the center of the political

maelstrom. The shortage caused

national attention to be focused upon

the enduring problem of slum hous-

ing--an urban problem which had existed

since the early nineteenth

century. By 1945, however, housing and

land use experts estimated that

one of every five American families,

primarily because of low income,

was forced to live in slum housing (by

modern standards) and that one-

fourth of all urban areas was

"blighted."7 Attempts at housing reform

had existed as long as the slums, but

not until the 1930's did the federal

government act decisively. Primarily in

hopes of reviving the prostrate

housing industry, the New Deal

established the Home Owners Loan Corp-

oration, the Federal Housing Administration,

and the nation's first public

housing program.8 Although

these New Deal programs made significant

contributions to housing reform,

Franklin D. Roosevelt never became

enthusiastic about them.9 Not so his

hand-picked successor, because Harry

S. Truman made housing one of his major

reform objectives and person-

ally devoted considerable attention to

its progress. This unprecedented in-

terest eventually helped achieve the

only major legislative victory of his

Fair Deal--the housing act of 1949.

This triumph resulted, however, because

a large number of Republicans,

led by Robert A. Taft, supported the

legislation in congress. The heart

of this act--810,000 units of federally

subsidized public housing--seemed

to its opponents to be socialism, or

even worse. Unlike most New Deal

reforms, public housing had never been

absorbed into the main stream

of American life. Nonetheless, the

supposed "conservative" leader not

only supported public housing but helped

develop its specific programs

and even co-sponsored the legislation

with two liberal Democrats. "Mr.

ROBERT A. TAFT AND PUBLIC HOUSING 137

Republican," therefore, played a

crucial role in the only significant legis-

lative victory of Truman's entire Fair

Deal.

Truman and Taft were normally outspoken

political foes, but they

concurred upon the need for

comprehensive housing legislation in the post-

war period. Although critical of the

overall tendency toward increased

federal regulation of the economy and

expanded welfare programs, Taft

endorsed public housing because it filled

a need which he believed the

private housing industry could not meet.

"Private enterprise," Taft said

bluntly, "has never provided

necessary housing for the lowest-income

groups."10 Basic to his interest in

housing reform was a belief that de-

cent housing was a prerequisite for good

citizenship. He saw in a happy,

healthy, well-housed family a microcosm

of the democracy. Because the

family provided the cornerstone upon

which the United States was erected,

good housing was vital. While many

Americans rejected public housing

as foreign to American ideals and

practices, Taft believed it to be the

only logical alternative to the

perpetuation of slum housing.11 As originally

conceived in the Wagner housing act of

1937, however, public housing

meshed neatly with Taft's deep

commitments to free enterprise, Christian

humanitarianism, and a locally rooted

democracy. No tenant could live in

a public housing project if he could

afford private housing, but conversely,

no family need live in a filthy tenement

either; "I feel that we have an

interest in seeing that there is

provided for every family in this country

at least a minimum shelter, of a decent

character, which will enable the

American family to develop."12

Public housing, as a pragmatic compro-

mise between the necessity of adequate

housing and a free economy, had

proved its value, Taft lectured the

senate in 1949:

I myself have visited many of the public

housing projects,

and they have accomplished much good. I

have gone through the

city of Cleveland, where such projects

have been built in some places

in what formerly were slum areas. The

public-housing projects have

not only improved the condition of the

people who live in them, but

they have raised the standard of the

entire neighborhood. ... I be-

lieve the Congress ought to adopt the

program and start the United

States toward the elimination of what I

think is the greatest social

evil in the United States today.13

Taft was not, however, a wild-eyed

utopian in his conception of public

housing. He viewed it solely as an

expedient; ideally, of course, private

housing would provide adequate housing

for all income groups. His deep-

seated commitment to the free enterprise

system demanded assurances

that public housing would never invade

the territory of private housing.

Any federal project would supply housing

only for those unable to rent

standard housing from private owners. He

viewed public housing cau-

tiously, because he did not want it to

shelter one family that could afford

decent private housing. Taft carefully

studied cost of living tables to

determine the minimum rent for such

housing; he was determined that

|

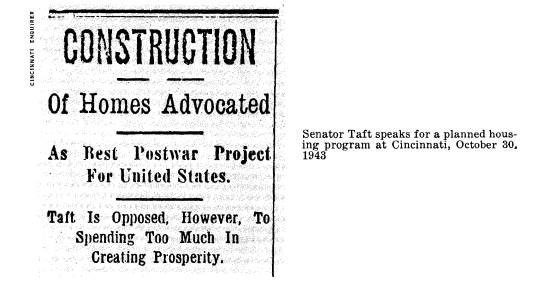

138 OHIO HISTORY public housing would not become, in any sense of the word, luxury hous- ing.14 The Cincinnatian, therefore, supported public housing, but simul- taneously prevented its more enthusiastic devotees from entertaining hopes of more elaborate possibilities. Taft did not support public housing simply to gain possible presiden- tial votes, as some critics charged, nor was his support an opportunistic response to the politically explosive housing shortage. As early as Feb- ruary 1942 he told the senate that housing would require some form of government planning in the post-war period.15 The comprehensive legis- lation which he ultimately co-sponsored had its immediate roots in the war years. Because the nation's urban areas were increasingly being rid- dled with large pockets of slum housing, a widespread movement devel- |

|

oped early in the war to "plan now for post-war housing."16 In 1943 the senate leadership responded by appointing Taft to chair a subcommit- tee on housing and urban redevelopment as part of an ambitious plan- ning program for post-war activities.17 Now cemented into an anti-New Deal position, the senate leadership desired to restrain any expansion of New Deal programs when the war ended. They apparently assumed that Taft would prevent any radical program from being adopted.18 The subcommittee hearings proved to be an educational experience for the senator. He approached the hearings with a desire to gather as much information as possible, and then to determine from the evidence the proper means of solving the problems that emerged. At the time the hearings began, Taft was not committed to public housing, as was fellow subcommittee member, the New York liberal Democrat, Robert F. Wagner. Taft dominated the hearings, most of which were conducted in early |

ROBERT A. TAFT AND PUBLIC HOUSING 139

1945. He encouraged detailed testimony

and frequently engaged in lengthy

questioning of the long parade of

witnesses. His time-consuming methods,

however, irritated Senator Wagner, who

already believed, in accordance

with his 1937 housing act, that only a

massive public housing program

would solve the problem of low-income

housing. At one point, when Taft

announced his intention of holding

further hearings, the New York Demo-

crat exclaimed in frustration, "I

don't think housing needs any more

investigation; I think it needs action."19 Wagner's

impatience proved

premature, however, because from the

more than two thousand pages of

testimony Taft concluded that the

housing industry was clearly unable

to provide low-income families with

adequate housing. And, he decided,

in agreement with Wagner, that only an

expansive public housing pro-

gram would provide the solution.

On August 1, 1945, Taft presented his

subcommittee's report to the

senate. The subcommittee based the

report upon the assumption that "from

the social point of view, a supply of

good housing, sufficient to meet the

needs of all families, is essential to a

sound and stable democracy." Be-

cause poor housing was a "deterrent

to the development of a sound citi-

zenry," the subcommittee

recommended a "comprehensive" program, with

emphasis upon public housing and urban

redevelopment. The subcom-

mittee emphasized the need for many aids

to private housing, but care-

fully pointed out that the continued

failure of the industry to provide de-

cent housing for low-income families

left the government with no al-

ternative but to expand the New Deal

public housing program. "The

justification for public housing must

rest on the proposition that the Fed-

eral Government has an interest in

seeing that minimum standards of

housing, food, and health services are

available for all members of the

community," the subcommittee

concluded.20

The post-war housing movement culminated

on November 14, 1945,

when Taft, together with Democrats

Wagner and Allen J. Ellender of

Louisiana, introduced a detailed and

complex bill embodying the major

features of the subcommittee report.21 By this

time President Truman

had wholeheartedly endorsed the

principles set forth in the report in his

September 6 message on reconversion. In

that message Truman told the

congress that decent housing no longer

could be considered a reward for

individual effort, but now should be a

right inhering in every American,

regardless of income. Truman urged

congress to pass appropriate legis-

lation to meet this ambitious goal.

"A decent standard of housing for all

is one of the irreducible obligations of

modern civilization," Truman told

the congress. "The people of the

United States, so far ahead in wealth

and production capacity, deserve to be

the best housed in the world. We

must begin to meet that challenge at

once."22 Although Truman now

made housing reform part of his Fair

Deal, Taft continued his unqualified

support of comprehensive housing

legislation.

Such action by the Ohio senator,

however, seemed far out of character.

His strong endorsement of public housing

and his willingness to co-

140 OHIO HISTORY

sponsor such "leftist"

legislation with the ultra-liberal New Dealer Wag-

ner, caused many explanations to appear.

Most generally, they were built

upon the assumption--apparently

false--that Taft was ready to sacri-

fice principle for presidential votes.

The New Republic, ignoring Taft's

role as originator of the bill, said,

"Taft's first step [toward securing the

nomination] was to jump on the housing

bandwagon and join Senators

Wagner and Ellender in sponsoring their

long-range housing bill." This

opinion journal warned that

"liberals in Congress must be suspicious

of Taft bearing the gift of political

support."23 Another liberal journal,

the Nation, blandly ignored the

fact that the Wagner-Ellender-Taft bill

was the largest housing bill ever

introduced in congress, and accused

Taft of sponsoring "a mild and

watered-down housing bill" to prevent

a truly effective one from being

passed.24 The National Association of

Real Estate Boards, the major lobby

group opposed to the bill, did not

engage in such subtleties. This

organization, through its membership

newsletter, charged Taft with fathering

a "Republican New Deal," and

lamented that Taft had become converted

to "socialism" in order to se-

cure labor's vote in 1948: "If a

candidate believes in public housing and

thinks he must have a little of it to

pacify the CIO, then he has to ac-

cept the implications. He does not any

longer believe in the American

private enterprise system. He is at

heart a socialist."25 Earlier, the same

newsletter had observed, "The

cynicism of Senator Taft and his associ-

ates who are leading the Senate away

from Constitutional principles and

fair play has never been equalled in the

history of any party."26 The

young liberal, Arthur M. Schlesinger,

Jr., however, saw a common-sense

approach to Taft's seemingly

out-of-character support of a New Deal-

Fair Deal program. Taft's "saving

grace," Schlesinger said, was a "clear-

cut logical intelligence and a basic

respect for fact." After his subcom-

mittee had collected its detailed

testimony, Schlesinger correctly observed,

Taft saw the need for public housing and

acted accordingly.27

Because of the pressing national housing

shortage, the Wagner-Ellen-

der-Taft bill received overwhelming

public support. The sense of urgency

was reflected in a speedy senate passage

on April 15, 1946.28 The bill,

however, died in the house banking and

currency committee, which was

dominated by a coalition of conservative

Republicans and rural southern

Democrats. Under the skillful leadership

of Republican Jesse Wolcott

of Michigan, the conservatives refused

to allow the bill to go to the house

floor. At one point, the committee even

refused Taft the privilege of

testifying for his own bill. Despite

great pressure from the White House

and public opinion, the bill died in

committee.29

In 1947, because of the election of the

first Republican congress since

the Hoover administration, Taft now

became the accepted leader of the

senate.30 The Ohioan continued to

support the housing bill, now renamed

the Taft-Ellender-Wagner bill in

deference to his majority leadership. He

found, however, that the rank and file

of his party opposed the bill. Taft,

nonetheless, labored hard for the bill

in 1947, but finally realized that

ROBERT A. TAFT AND PUBLIC HOUSING 141

passage was impossible. Confronted by

the virtual assurance of a repe-

tition of the previous year's action in

the house banking committee, and

a general Republican discomfort over

public housing, Taft decided to

abandon his bill for the year. When

challenged on his failure to place

his own bill on the senate agenda, Taft

with his usual candor, told the

senate that he had removed the bill from

his "must" list because the pub-

lic housing feature would prevent its

passage; the senate, he said, would

only waste valuable time on the bill

because its consideration by the

house was unlikely.31

In the presidential election year of

1948, Taft doggedly continued his

support of housing reform, even though

Truman had turned housing into

a major political issue.32 The senate

passed T-E-W on April 22 by ac-

clamation and again the bill went to the

house banking committee;33

the bill's supporters hoped that the

pressure of an election year would

force the committee to approve the bill.

Surprisingly, this is exactly

what happened, but the rules committee

promptly killed the bill.34 For

three consecutive years, therefore, an

important bill, which had extensive

public support and was virtually assured

of easy passage, died without

the house of representatives ever having

the opportunity of voting on

the measure.

The solidly entrenched anti-reform

conservatism of the house bank-

ing and rules committees, which openly

flouted the basic principles of

democracy and representative government,

embarrassed the Republican

leaders, who had serious intentions of

ending sixteen years of Democratic

occupancy of the White House. Even Taft,

himself a leading presidential

aspirant, could not persuade his fellow

Republicans in the lower house

to pass the bill. Wolcott, assisted by

Leo Allen's rules committee, Speaker

Joe Martin, and whip Charles Halleck,

presented a united front against

the bill. Republican Senator Ralph Flanders

of Vermont recalls the situa-

tion in his memoirs: "House

sentiment was strongly against public hous-

ing. There is in my memory a clear

picture of Taft backing Joe Martin

up against the wall of the Senate

chamber and demanding in no uncertain

terms that the House accept the

bill."35 This, as well as all other per-

suasion techniques, proved futile.

When Truman called congress back into

special session after the

nominating conventions, supposedly to

take emergency action on inflation

and housing, Taft bitterly criticized

the move as blatantly political.36

But Truman had cleverly exposed the

sharp division of counsel in the

Republican ranks--the GOP platform

endorsed a comprehensive housing

program, including public housing, but

its leadership in the house adam-

antly opposed such legislation. Trapped

between the liberalism of their

platform and the conservatism of their

congressional leadership, the Re-

publicans were simultaneously embarrassed

and angered when they re-

assembled in steamy-hot Washington on

July 26, or "Turnip Day," as Tru-

man said his fellow Missourians called

it. Truman, the Republicans said,

had resorted to cheap Missouri politics

of the Pendergast variety; several

142 OHIO HISTORY

leaders even suggested adjourning within

minutes after the special ses-

sion opened.37 In a formal statement the

Republican leadership denied

that housing or prices required

immediate attention and condemned Tru-

man's action as the last desperate

gamble of a doomed politician. The

Republicans said, however, that they

would study Truman's proposals and

privately agreed to pass a housing bill,

but one bereft of the controversial

public housing section. To prevent any

open public split within the party

that had adopted the theme of

"unity" for its presidential campaign, the

leaders decided to prevent the perennial

T-E-W bill from escaping the

senate banking committee. For the sake

of his party's "unity," Taft

agreed to this, but simultaneously

affirmed his intention of re-introducing

the bill in 1949.38

This politically motivated compromise

failed to work, however, because

two liberal Republicans, Senators

Flanders and Charles Tobey of New

Hampshire, voted in committee with five

Democrats to send the bill to

the senate floor. Both were deeply

disturbed by what they believed to be

a denial of the democratic process, and

so undermined their party's care-

fully developed plans.39 This unforeseen

development placed Taft in an

unusually uncomfortable position.

Because he had agreed to prevent the

bill from reaching the floor of the

upper house until after the election,

the two New England insurgents forced

him to oppose his own bill. Caught

squarely in the middle of his party's

liberal-conservative feud, Taft stood

by his agreement. Public housing, he

said, would prevent passage of the

other important provisions of the bill;

a limited bill, containing many

"aids" to private housing,

would be better than no bill at all. He assured

the senate that he had previously done

everything possible to persuade

the house leadership to allow a vote on

T-E-W. He was still for public

housing, but it was not possible then.40

Democratic vice-presidential

nominee, Senator Alben W. Barkley of

Kentucky, did not allow this golden

moment to pass; seldom did Taft allow

himself to be trapped in such an

embarrassing position. Barkley's sarcasm

filled the senate chamber. "The

Senator from Ohio," he observed,

"apparently has surrendered his position.

. . . I do not myself propose to

surrender my convictions."41 The Flan-

ders-Tobey revolt failed, however, but

Republican "unity" had been shat-

tered on the senate floor, with an

amused Harry Truman looking on. The

congress eventually passed the

"Housing Act of 1948," but it contained

only minor provisions for federal loans

to apartment builders. Truman's

strategy to expose the sharp cleavage in

his opposition's ranks had proved

extremely successful. All he had done,

he said, was to give the Republican

eightieth congress an opportunity to

show the voters if it really sup-

ported its party's platform. Its

refusal, he said, raised serious questions

about the sincerity of the Republican

leadership.42

Taft's action on housing during the

bizzare special session provided

Truman with a good example of what he

considered to be Republican du-

plicity. During the ensuing campaign

Truman often told his audiences

along the railroad tracks how "Taft

ran out on his own bill."43 "He tried

ROBERT A. TAFT AND PUBLIC HOUSING 143

to pose as a man who wanted decent

housing legislation," he told an

audience in Taft's own Cincinnati,

"but after his defeat at the Republi-

can convention in Philadelphia, Taft

didn't have to carry on his pretense

of caring about the needs of the people.

He could act in his real character

--as a cold-hearted, cruel

aristocrat."44

The Ohio senator, however, did not

support housing reform purely for

political considerations, because he

continued his support and sponsorship

of an expanded version of the old T-E-W

bill in 1949. The bill, sponsored

this time by ten members of each party,

eventually passed congress after

bitter debate; Truman signed it into law

on July 15, 1949.45 This action,

the high point of Fair Deal legislation,

was also the zenith for housing

reform in the United States.46 The

political wars of 1948 forgotten, Taft

wrote Truman that he believed the

passage of the bill to be "an historical

occasion." "I am

hopeful," he wrote, "that the present Act will initiate a

program of public and private housing

which will lead to a solution of

our housing difficulties, and bring

about ultimately a condition in which

decent housing is available to

all."47

Taft's contribution to Fair Deal housing

legislation was threefold. He

gave the legislation the necessary

bipartisan support to enable it to pass

the senate; about twenty Republicans

followed his leadership on hous-

ing. Without these votes the bill would

never have become law. Taft also

gave the bill the endorsement of

responsible conservatism; frequently,

liberals cited Taft as an example of an

enlightened conservative who saw

public housing in its correct perspective.48

Finally, Taft served as a

brake upon more avid public housing

enthusiasts, who preferred a far

more expansive program, which probably

would have alienated many

moderates who supported the bill. Many

conservatives, however, did not

follow Taft's leadership, and as they

watched his actions in near-disbelief,

could only mutter, "Taft is

becoming a damn Socialist."49

THE AUTHOR: Richard O. Davies is

an assistant professor of history at

Ari-

zona State College, Flagstaff. He is the

author also of "Whistle-Stopping

Through

Ohio," an account of President

Truman's

campaign tour of Ohio in 1948, which ap-

peared in the July 1962 issue of Ohio

His-

tory.