Ohio History Journal

NANCY SAHLI

A Lost Portrait?

Frank Duveneck Paints

Elizabeth Blackwell

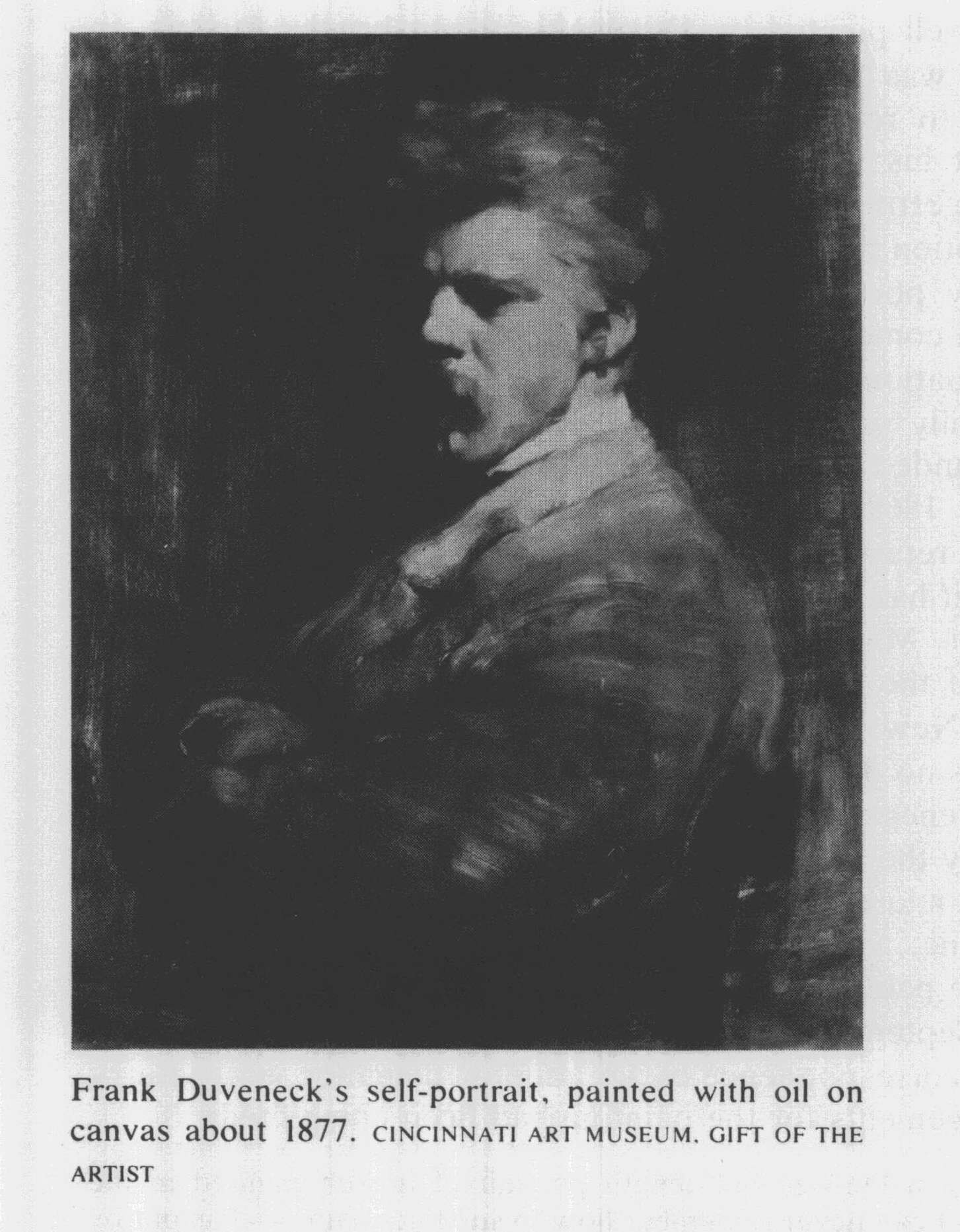

Frank Duveneck was probably Ohio's best

known artist during the

late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries, and is certainly one

whose reputation has been sustained to

the present day. Born in

Covington, Kentucky, in 1848, he began

his career decorating

churches in the United States and

Canada. In 1870 he traveled to

Munich to study with Wilhelm von Diez,

returning three years later to

Cincinnati. By 1877, Duveneck's

reputation had been firmly

established, chiefly as a result of his

one-man show two years before

at the Boston Art Club. Indeed, it was

Henry James who remarked in

his article on the exhibition in The

Nation that "the discovery of an

unsuspected man of genius is always an

interesting event, and

nowhere perhaps could such an event

excite a higher relish than in

the aesthetic city of Boston."1

Despite the inducements, however,

which Duveneck received to stay in that

city, including several

immediate orders for portraits, the

artist decided to return to Europe.

Not until 1890 would he return to

Cincinnati and to a distinguished

teaching career which lasted until his

death in 1919.

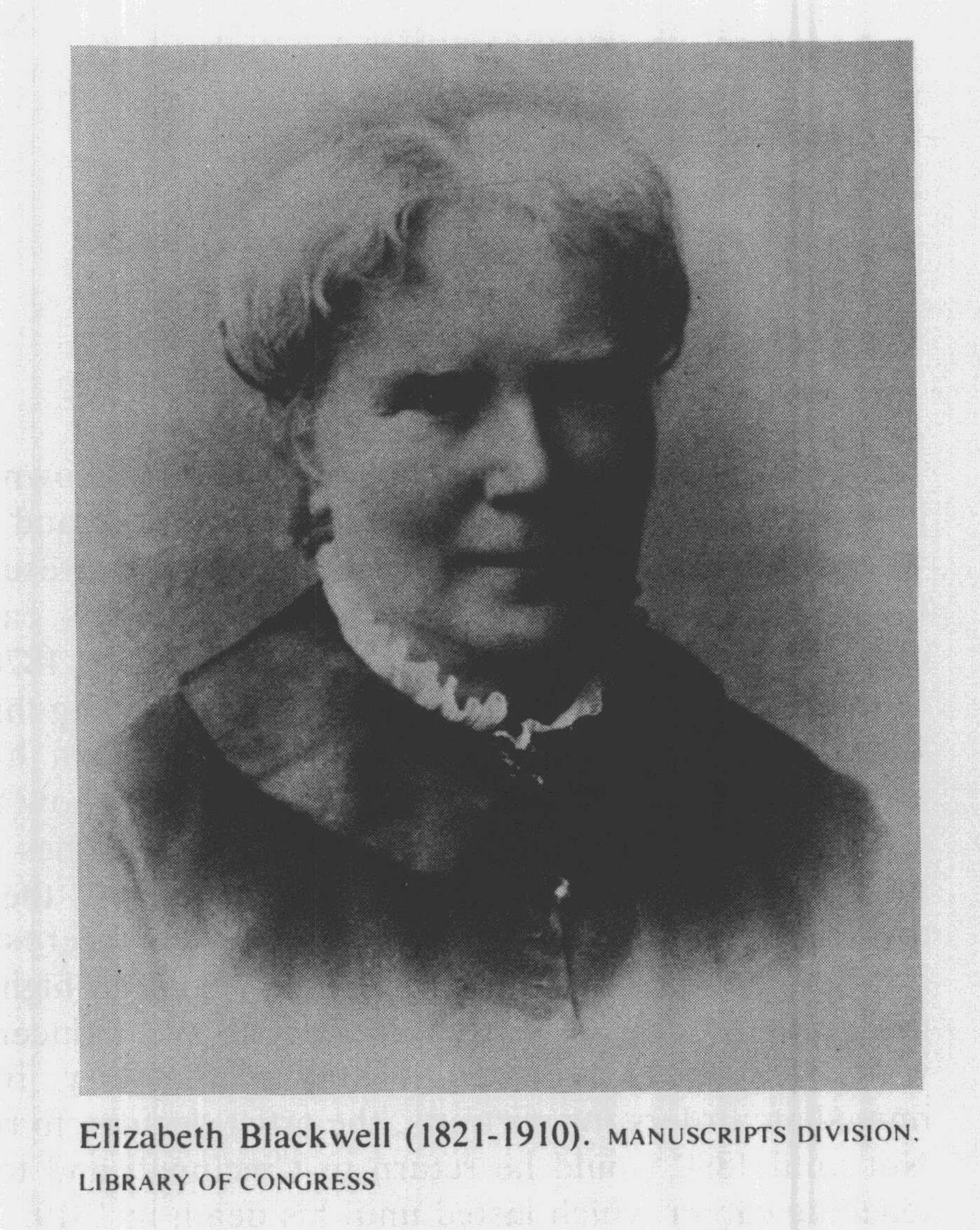

Around the same time that Duveneck was

born, in 1848, another

Cincinnati resident, Elizabeth

Blackwell, was beginning her second

year of study at Geneva Medical College

in Geneva, New York. She

was a native of Bristol England; in

1832, at the age of eleven, she had

emigrated to the United States with her

family. In 1838, after

spending a few financially unsuccessful

years in New York City, the

Blackwells moved to Cincinnati, where

Elizabeth's father, Samuel,

intended to start a sugar refinery. His

unexpected death shortly after

their arrival ended this scheme, and as

a financial necessity the family

organized a school, the Cincinnati

English and French Academy for

Dr. Sahli is a graduate of Vassar

College and The University of Pennsylvania, and is

employed currently as an archivist for

the National Historical Publications and Records

Commission, Washington, D.C.

1. Mahonri Sharp Young, "Duveneck

and Henry James: A Study in Contrasts,"

Apollo, XCII, no. 103 (September 1970), 212.

|

320 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

Young Ladies. Elizabeth taught there for a few years, but by 1845 she had decided to pursue a medical career. After two years of private study she was accepted at the Geneva school, where she graduated in 1849, thereby becoming the first woman medical school graduate in the United States. Throughout the years, an accepted part of Duveneck scholarship has been that in 1877, on his way from Germany to Italy, the artist stopped briefly in Austria, where he painted a portrait of Susan B. Anthony, one of the leaders of the American women's suffrage movement.2 The truth of this assertion is, however, highly suspect.

2. See Ibid., 213; Cincinnati Museum Association, Exhibition of the Work of Frank Duveneck (Cincinnati, 1936), 81; Josephine W. Duveneck, Frank Duveneck: Painter-Teacher (San Francisco, 1970), 66-67; Frank Duveneck (New York, 1972), unpaged. The Cincinnati exhibition catalogue claims that the portrait was done in 1887, while the Young article gives Salzburg, rather than Innsbruck, the more commonly |

|

Frank Duveneck 321 |

|

|

|

There is no example in the Duveneck literature of either a photographic reproduction or a verbal description of the work. Moreover, in the spring of 1877 Susan B. Anthony was in Kansas caring for her dying sister, Hannah Mosher. There is also no reference in the standard biography of Anthony to any portrait by Duveneck.3 There is, however, in the Blackwell Family Papers in the Library of Congress, correspondence describing a portrait of

accepted site, as the location of the sitting. Various companions, such as Louis Ritter, John W. Alexander, William Merritt Chase, and John H. Twachtman, are alleged by these authors to have accompanied Duveneck on his way from Munich to Italy. However, since no such companions are mentioned in the Blackwell papers, which are apparently the only surviving documentation for this period of Duveneck's career, it would seem most probable that he made the journey alone. 3. Ida Husted Harper, The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, 3 vols. (Indianapolis, 1898-1908). Susan B. Anthony did not make a trip to Europe until 1883 |

322 OHIO HISTORY

Elizabeth Blackwell painted by Duveneck

in Innsbruck, Austria, in

1877. The error was probably originally

perpetrated by Duveneck

himself. Trying to recall whom he had

painted in Innsbruck, he

remembered that his sitter was a leader

in the American women's

movement. Forgetting her name, he or

someone else made the

mistaken assumption that it was Susan B.

Anthony. It is now evident

that an Anthony portrait never existed.

Likewise, the Blackwell

portrait has been completely unknown to

Duveneck scholars.

After her graduation from medical

school, Blackwell had studied in

Europe, and finally settled in New York

City, where she practiced

medicine and founded the New York

Infirmary, a hospital for women

and children. By 1869, however, she had

given up her career in the

United States to return to her native

England. In all probability, the

Blackwell portrait had its inception at

the time of Duveneck's Boston

show in 1875. Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, who

commissioned the work,

was a resident of the city, a former

colleague of Blackwell, and the

founder of the New England Hospital for

Women and Children.

Although there is no documentary

evidence regarding her decision to

commission Duveneck to do the portrait,

it can be inferred that she

was impressed by the artist's work at

the Boston exhibit and decided

that Duveneck would be a suitable artist

to paint Elizabeth Blackwell.

In the meantime, a decision had to be

made regarding where the

portrait would be painted. Blackwell had

been on a grand tour of the

continent since September 1876. By March

1877 she was in Italy, and,

according to the correspondence of her

adopted daughter, Kitty Barry

Blackwell, arrangements for the painting

had been completed:

Aunt B. is to have a life-size

half-length portrait of herself painted in the

Tyrol. Dr. Zack - I can never remember

how to spell her name - has put by

a sum for the purpose, means to have the

painting exhibited in the Boston

Fine Arts Gallery all winter, then keep

it while she lives, bequeathing it, on

her death, to the N. York Infirmary. We

are in correspondence with an Artist

about the picture. I hope it will be

well done - if it be, I shall have photos

taken from it.4

The decision to paint the portrait in

the Tyrol, rather than in Munich,

Duveneck's European base, was due

largely to the artist's increasing

dissatisfaction with his situation in

Germany. In February 1877

Duveneck commented on his discontent in

a letter to his friend John

M. Donaldson. "Munich," he

began,

4. Kitty Barry Blackwell to Alice Stone

Blackwell, March 24, 1877, The Blackwell

Family Papers, Library of Congress.

Original punctuation and spelling have been

retained in this and subsequent

quotations. The Blackwell-Duveneck correspondence

apparently has not

survived.

Frank Duveneck

323

has taken a great change since you left

aspecially among the American boys

.... Munich will be quite deserted from

the older American boys before long.

Chase is very anxious to make a change

and will probably be in Paris by next

summer, I have also an intension of

going to Paris or London by next

summer, Munich is very much plead out in

the way of art there is nothing

done whatever and no pictures bought at

all and I don't know but what I

would do better to get out of Munich as

soon as possible.5

Duveneck did just that. By late spring,

no doubt influenced by the

prospect of the Blackwell commission, he

had decided to summer in

Italy, and proceeded south from Munich,

stopping in Innsbruck,

Austria, to paint the portrait.

Blackwell likewise arrived there in late

April, accompanied by her daughter.

Actual work on the painting began May 2,

1877, as Elizabeth

Blackwell tersely noted in her diary:

"Mr Duvernack began

portrait."6 It is

fortunate that Kitty Barry Blackwell corresponded

frequently with Dr. Blackwell's niece,

Alice Stone Blackwell, for it is

these letters that shed the greatest

light both on Frank Duveneck's

method of painting and the working relationship

between him and his

sitter. By May 8, when Kitty wrote her

first letter to Alice describing

the portrait, substantial progress had

already been made:

The great work is fairly underway. Today

Aunt Bessie is giving her Seventh

Sitting for her portrait to Mr Duverneck

(Aunty encloses a note for Dr Zack

to ask that Mr D's money be sent to

Venezia). It was very odd that, after the

first sitting, when the background was a

dull Indian-red, & Aunty's body was

outlined in a still duller red, her face

white, with only touches of colour where

the shadows were to fall. Mr D has

contrived to give a most agreeable

likeness, with a very marked reminder of

Grandma in it. I never noticed a

likeness to Grandma in Aunty before.

However, the picture looks at present

like a Spirit-photo of Aunt B. Did you

ever see those queer Spirit-photos? If

Aunty departed and I attended a Seance

the medium wd contrive (if she knew

anything of us) to make just such a dim

misty-suggestion of Aunt B. to appear

to me. I think Mr D is clever & I

hope he'll succeed. He is an American -

born in Kentucky. You will be able to

judge results for you will see Aunty

exhibited at the Club & Gallery in

Boston next winter.7

Within a few days it was obvious that

artist and subject had de-

veloped a friendly working relationship,

although Blackwell's mater-

nal interest in Duveneck never

progressed to the point of adoption:

5. Frank Duveneck to John M. Donaldson,

February 17, 1877, The Papers of John

M. Donaldson, Archives of American Art,

Smithsonian Institution. The Papers of

Frank Duveneck at the Archives of

American Art do not contain any material relating

to the portrait.

6. Elizabeth Blackwell, Diary, May 2,

1877, Blackwell Family Papers.

7. Kitty Barry Blackwell to Alice Stone

Blackwell, May 8, 1877, Ibid.

324 OHIO HISTORY

Aunt B is being painted in the next room

& as the light from my door is

unfavorable, it has been shut. The

picture is getting on splendidly & I think

will prove a great success. At any rate

Mr Duveneck is not discontented with

his subject, for he expresses a wish

that he may paint Aunty again & in his

own studio.

Aunty is beginning to take an interest

in Mr D. I think if we remained long

he would be a second case of adoption.

Aunty used to say she should adopt

"six young men." I'll not

allow her to go beyond six at any rate.8

Elizabeth Blackwell's last sitting was

on May 18, and the following

day she treated Duveneck to dinner

before his departure for Venice.

Kitty set down her final thoughts on the

work as well as on Frank

Duveneck in a letter to Alice of May 24:

On the 19th Mr Duveneck finished the

portrait & the same p.m. it was started

on its journey to Boston. It is an

admirable portrait in every way & I think

would always bring Dr. Zack more than

she has paid for it, because it is a real

work of art. You know it is to be

exhibited this Winter at the Fine Arts Club

and later at the Boston Museum. I

withdraw any embargo as to speaking of

the picture. I hope it will be liked and

that it may bring Mr Duveneck other

commissions. If ever you see any notices

in Boston papers about the picture,

please send them to me, that Mr. D may

see them. He is a good artist, but his

general education is very limited. It is

disappointing to find so unusually

clever an Artist speaking bad grammar

& so unpolished in his manners. Aunt

B. has given him some hints which I

think may help him.. . . We gave Mr D.

a dinner to celebrate the great work

being over & afterwards Mr. D. started

for Venice.9

Unfortunately, the haste with which the

painting was sent to the

United States was not to its ultimate

good, as Elizabeth Blackwell

wrote to her friend Barbara Bodichon in

November of 1877:

The large life size portrait for which I

gave up so much time at Innsbruck,

reached Boston with its packing case

quite destroyed, its handsome frame

broken to pieces, and its background

very much damaged. Fortunately no

injury was done to the face or more

delicate parts of the picture, and it has

given great satisfaction, being

considered a fine work of art.10

Here the story of the Blackwell portrait

comes to an abrupt end. A

survey of Boston art exhibit catalogues

and newspaper notices from

1877 to 1880 indicates that the painting

was never exhibited as

planned, its damaged condition probably

militating against this.11

8. Kitty Barry Blackwell to Alice Stone

Blackwell, May 10, 1877, Ibid.

9. Kitty Barry Blackwell to Alice Stone

Blackwell, May 24, 1877, Ibid.

10. Elizabeth Blackwell to Barbara

Bodichon, November 15, 1877. The Elizabeth

Blackwell Collection, Special

Collections, Columbia University Library.

11. Materials consulted include the

collection of exhibit catalogues in the library of

the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and

such newspapers as the Boston Daily Globe and

the Boston Evening Journal.

Frank Duveneck

325

There are no photographs of the work,

such as Kitty Barry Blackwell

wanted to be made, in the collections of

Blackwell family papers at

the Library of Congress and the

Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe

College. There is no mention of the

portrait in Marie Zakrzewska's

will, and, indeed, no mention of any

bequest to the New York

Infirmary.12 The portrait

does not hang in the halls of the Infirmary,

nor is there any record of its ever

having been there.13

Does the portrait still exist? Are there

other Duveneck paintings,

not to mention those by other artists,

whose existence is noted only in

manuscript collections generally falling

outside the purview of art

historians? Although the portrait itself

may be lost, it is hoped that

this historical identification has been

a useful focal point for

presenting some new insight into the

lives of Elizabeth Blackwell and

Frank Duveneck. Now, someone, find the

portrait!

12. Marie E. Zakrzewska, Will, January

23, 1901 (Docket No. 120708, Suffolk

County Probate Court, Boston, Massachusetts). Since

"pictures" were one of the

categories of items left by Zakrzewska

to her brother-in-law Albert Crouze and his son

Herrman of Brooklyn, New York, it is

possible that the portrait passed into their

hands.

13. John P. DaVanzo, Assistant

Administrator, New York Infirmary, to author,

October 13, 1975.