Ohio History Journal

G. WALLACE CHESSMAN

Town Promotion in the Progressive

Era: The Case of Newark, Ohio

On July 8, 1910, an angry mob stormed

the county jail at Newark,

Ohio, seized a young, white "dry

detective" being held there, carried

him off to the courthouse square and

lynched him.1 That violent act

stunned local leaders who had long

promoted their booming industrial

town in Licking County as "the best

place in Ohio to live and work."

At the same time it dramatized the

inter-city struggle that had long

engaged business interests in most

American cities of that era, as each

sought to outdo its closest rivals in

the competition for growth.

Town promotion has a history going back

to the "urban frontier"

of the late eighteenth century. Few

American communities did not have

boosters seeking to attract new

migrants, new means of transport,

new institutions public and private. By

the 1850s civic leaders in Cin-

cinnati, Cleveland, and Columbus had

formed local associations to pro-

mote trade in a regular, systematic

fashion. With the rise of manufac-

turing in the post-Civil War period, the

focus of inter-city rivalry east

of the Mississippi shifted to the

acquisition of new industry. It was into

this latter competition that Newark and

other towns of similar size soon

entered.2

Characteristically, Newark promoters

approached their work in a pa-

rochial fashion. They did not place

their efforts within a historical con-

G. Wallace Chessman is Professor of

History at Denison University, Granville,

Ohio.

1. A "dry detective" was a

private individual hired by prohibitionists to enforce local

liquor laws.

2. On earlier efforts at town promotion,

see especially Richard W. Wade, The Urban

Frontier: The Rise of Western Cities,

1790-1830 (Cambridge, 1959), Chapters

1-2, 6, 10;

Daniel J. Boorstin, The Americans:

The National Experience (New York, 1965), Part

Three; Harry N. Scheiber, "Urban

Rivalry and Internal Improvements in the Old North-

west, 1820-1860," Ohio History, LXXI

(October 1962), 227-39, 290-92; Charles N.

Glaab, Kansas City and the Railroads (Madison,

1962); Blake McKelvey, The Urbaniza-

tion of America 1860-1915 (New Brunswick, 1963), Chapter 2; Kenneth Sturges,

American Chambers of Commerce (New York, 1915). See also Henry L. Hunker, Indus-

trial Evolution of Columbus, Ohio (Columbus, 1958). Milwaukee's Chamber of Com-

merce was one of the first to raise a

fund to "promote the city's industrial growth," in

1869; see Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The

History of a City (Madison, 1948; rev. ed., 1965),

348-53.

254 OHIO HISTORY

text, nor did they generalize broadly

about American developments;

theirs did seem in the 1880s an

"island community" such as Robert

Wiebe has described. From examples close

at hand they nevertheless

derived some notion of wider influences,

whether in schemes for at-

tracting industry or later in programs

for civic improvement. Through

three and a half decades after 1880

their town would become ever more

involved in the new urban-industrial

system that was destroying auton-

omous communities across the land.

Theirs would indeed be an evolu-

tion typical of small-town America

during the Progressive Era.3

To contest with other cities at all

required certain "natural advan-

tages" that Newark boosters

appreciated. Situated in a farming area

that in the 1880s led all Ohio counties

in wool production, their town

was a logical market center. To the

south were abundant coal fields,

while the Licking River valley assured a

copious supply of water; and

in 1887 drillers brought in the first of

many wells from the natural gas

and oil beneath Licking and Knox

counties. "Columbus is green with

envy over Newark's success in the

natural gas line, and her press

sneers at 'these fools from Newark who

blow their money in the gas-

hole'," the Newark Advocate soon

reported. "Regards to Columbus.

These fools from Newark will come over

and buy your village presently,

and make a base ball park out of

it."4

To these natural advantages were added

those of transport. By the

1880s Newark citizens no longer prized

their access by the Ohio Canal

to Cleveland, or to Portsmouth on the

Ohio River, but the Baltimore

and Ohio and the Pennsylvania's

Panhandle line gave them first-class

rail facilities in all directions. The

National Road between Zanesville

and Columbus passed six miles to the

south, and the Toledo and Ohio

Central Railroad from Pomeroy to Toledo

passed three miles to the

west, but neither of these tricks of

fate seemed crucial to business.

Newark soon connected with T.&O.C.

at the college town of Granville

over the electric interurban completed

in 1890.

Beyond natural advantages and transport,

men valued the social and

cultural character of a community.

Newark's population of 9,900 in

1880, which was almost to triple by

1910, was for the most part law-

abiding and moral, interested in good

schools and attractive churches

and decent entertainment. A substantial

minority of first- and second-

generation immigrants supported a

German-language weekly, the New-

3. Robert H. Wiebe, The Search for

Order 1877-1920 (New York, 1967).

4. Newark Advocate, June 23,

1887. The Licking-Knox discoveries were less spectac-

ular than the great Karg well at

Findlay, Ohio, but had much the same impact described

for the Indiana field by the Lynds; see

William D. Humphrey, Findlay: The Story of a

Community (Findlay, 1961), and Robert S. and Helen M. Lynd, Middletown:

A Study in

American Culture (New York, 1929).

Town Promotion in Newark

255

ark Express, while most Republicans subscribed to the American,

and most Democrats to the Advocate. College-bound

youth looked

first to Granville's two female

seminaries and to its men's college,

Denison University. Along Gingerbread

Row and near the B.&O. sta-

tion were many bars and sporting houses,

as in any railroad town, but

around the public square were a Music

Hall and several excellent res-

taurants.

In fact Newark had so many advantages,

argued Common Pleas

Judge Samuel M. Hunter in 1882, that its

prosperity was only being

retarded "by the careless and

disparaging talk of its own citizens, and

by the ill-will of its neighbors. It has

natural advantages that are equal

to any inland city in the State; its

population, in intelligence, and all

that goes to make up a good community,

is surpassed by none of its neigh-

bors; its public schools are the peer of

any in Ohio; its health is un-

equalled; and it is the county seat of

one of the very best counties in

the great State of Ohio."5

Hunter and other boosters agreed with Advocate

editor J. H. Newton

that what Newark needed was "more

manufactories." In 1880 the city

had a carriage works, several foundries,

a glass plant, some machine

shops, flour and planing mills, but all

were small-scale operations;

by far the largest employer was the

B.&O., with some two hundred

men in its yards and shops. Newton did

not hold out much hope for

acquiring "rolling mills, blast

furnaces, nail works, potteries and the

like"; rather he wanted "some

works . . . to meet the requirements of

the farmer and local commerce,"

such as a factory producing agricul-

tural implements, or furniture, or a

score of other products "so largely

used in this community, which are now

brought from a distance." To

establish new industries that would fill

chiefly rural needs, and to in-

duce Licking County residents to do more

buying "at home"-that

was Newton's formula for growth.6

The great obstacle to this plan was the

paucity of private local capi-

tal to establish or attract new

industry. To fill the gap the city issued

municipal bonds. In 1881, under an Ohio

law which Canton, Spring-

5. Advocate, February 24, 1882. Newspapers are the central and

essential sources for

this study, and the Newark Advocate is

especially useful because its proprietors followed

Board of Trade doings so carefully and

fully; the weekly or semi-weekly editions (which

are usually used in this article prior

to 1916) carry all the major stories from the daily,

usually identified by the day itself.

The most recent study of Newark and Licking County

is Gordon R. Kingery, A Beginning (Newark,

1967); older works, of most use for the

earlier years, are N. N. Hill, Jr.,

comp., History of Licking County, 0., Its Past and Pres-

ent (Newark, 1881), and E. M. P. Brister, Centennial

History of the City of Newark and

Licking County, Ohio (2 vols., Columbus, 1909).

6. Advocate, August 20, 27, September 3, 10, 1880. An engaging

reminiscence of

family life in Newark then is Robbins

Hunter, The Judge Rode a Sorrel Horse (New

York, 1950).

256 OHIO

HISTORY

field and Delaware had each employed

previously, the voters of Newark

approved issuance of "Machine Shop

Bonds" to assist industries that

would locate there. The city council

authorized $50,000 in six-percent

bonds, from which $37,500 was to be

devoted to relocating the Hagers-

town (Md.) Agricultural Works. Renamed

the Newark Machine Com-

pany, the new factory functioned

successfully for two years, whereupon

a fire and a drawn-out insurance dispute

necessitated transfer of oper-

ations to rented facilities in Columbus.

Not until over a decade later,

and then only after a financial

concession by the city and a $5,000 sub-

scription drive by the Board of Trade,

was Newark Machine to return

to its West End site.7

In 1887 city business interests formed a

Board of Trade. Hitherto

it had been up to individuals or ad hoc

groups, in the informal, unor-

ganized way of the small town, to

advance some manufacturing project

or to agitate for an improvement in

municipal services. The weakness

of such disjointed efforts had become

apparent in ill-directed campaigns

to secure a rail connection with the

T.&O.C. and to construct a munici-

pal water plant. And from their

"island community" Newark boosters

had to look no further than Columbus to

see that the Board of Trade

there was so well established that it

was about to construct its own

building. Even Zanesville had had a

trade association since 1868; in-

deed, in forming such a body Newark

would only be doing what city

after city had been doing since the

Civil War. By 1886 the Newark

American was calling for a "Board of Commerce" to do

something

about relocating a Columbus shoe firm in

the city. In February 1887 the

Advocate simply announced that the "Board of Trade"

had obtained a

new industry, the Newark Wire Cloth

Manufacturing Company.8

The first president of the Newark Board

was a dry goods merchant;

the secretary, a prominent grain dealer.

At annual elections subse-

quently the body also elected a

vice-president, a treasurer, and a board

of directors. Local railroad officials,

bankers, lumber dealers, real estate

brokers, builders, lawyers, editors, small-business

proprietors, man-

agers in various enterprises-such men

made up the membership. Labor

unions were not represented, nor did

clergymen, doctors, or city officers

7. Advocate, April 8, May 20, 1881; July 10, 1884; November 8, 1894.

8. Newark American, December 2,

1886; Advocate, February 24, 1887. McKelvey,

Urbanization, 42-45. The Columbus Board of Trade was first formed in

1858; it had to

be re-formed in 1866, 1872, and 1884,

and in December 1886 resolved to construct its own

building, finally completed in 1889.

Osman C. Hooper, History of the City of Columbus,

Ohio (Columbus, 1920). 263-64. On the Cleveland Board of

Trade, first formed in 1848

and reorganized as the Cleveland Chamber

of Commerce in 1893, see William G. Rose,

Cleveland: The Making of a City (Cleveland, 1950). Cincinnati boasted the state's old-

est commercial body; see Philip D.

Jordan, Ohio Comes of Age, 1873-1900, vol. V of

Carl Wittke, ed., The History of the

State of Ohio (Columbus, 1943), 243.

Town Promotion in Newark 257

usually participate, but the community's

business interests, both mer-

cantile and industrial, were well

represented.

Initally Board leaders did not visualize

a financial role for the organi-

zation. Acquisition of the wire cloth

firm had involved no bonus, nor

were members assessed for a fund to

attract industry. Instead, influ-

enced quite obviously by the Columbus

Board of Trade, Newark direc-

tors in 1889 helped to organize "an

Industrial association-an associa-

tion of the people-to co-operate with

the board of trade of this city in

securing new manufacturing enterprises

and in developing the city's re-

sources in a manner commensurate with

her many natural advantages."

In a public letter a former

vice-president of the Board urged "every citi-

zen to become a member of the Industrial

Aid Society," which was de-

signed "for and within the reach of

every citizen, and if the people give

it the aid it deserves, Newark will soon

be placed to the fore front as

one of the best cities of the

state."9

Few citizens gave their dollars to the

new society, yet the Board soon

learned how useful such a fund might be.

In November 1889 a New

York promoter who had organized the

city's first horse-car railway

company offered to build a rail

connection with the T.&O.C. if citizens

would "donate the comparatively

small sum of six thousand dollars

toward the project." Hurriedly a

subscription paper was circulated;

within a week the sum was pledged.

Though the scheme eventually

fell through, the lesson was clear: the

Board needed capital if it was to

exploit opportunities.10

"Newark is just now at that point

in her history when she must take

aggressive steps to insure her progress

or she will retrograde to the point

where the property now owned will

depreciate in value to an alarming

extent," the American pointed

out in March 1890. "Not a week passes

that members of the Board of Trade do

not receive proposals from

manufacturing institutions working from

fifty to five hundred hands

who want to locate in our city if we can

give them a little help." If we

can give them a little help-that was the crucial element. "At present the

Board of Trade and the city council are

without a cent to aid in this di-

rection," editor W. C. Lyon quickly

noted, "and as a result other cities

are securing these institutions, and are

gaining upon us in point of popu-

lation and commercial standing, . .

."11

On March 6, 1890, this Republican paper

enthusiastically endorsed

the Board of Trade's request that the

city council call a special munici-

pal election asking the legislature to

pass an enabling act giving a cer-

9. W. H. S. (William H. Smith) to the

editor, Advocate, October 31, 1889.

10. Ibid., November 7, 1889; see

also June 30, 1887, and American, July 19, 1888.

11. Ibid., March 6, 1890.

258 OHIO

HISTORY

tain sum of money to be used in getting

manufacturing plants located

in the city. Within a month Newark

leaders had obtained a state law

permitting city council to authorize

$60,000 in bonds and to levy taxes

in order to assist manufacturers. In

June 1890 the citizens gave their

approval by a majority of 158 in a total

vote of 1,334.12

The first applicant to the Board of

Trade and city council for a portion

of these new funds was young E. H.

Everett, who in 1880 had taken

over the Newark Star Glass works and now

was anxious to convert

from pots to the more efficient

continuous-tank system of manufacture.

Everett's request for $50,000 for his

plant (maker of "the best self-seal-

ing lightning fruit jar in the world . .

. the best and most extensively

used rubber stopper bottle") struck

some councilmen as much too large;

negotiations stalled until a committee

of the Board of Trade concluded

from extensive investigation that

"continuous tank furnaces are the

coming system for the manufacture of

glass" and that an efficient in-

stallation would require a $52,900

investment. By making the building

only partly fireproof the cost could be

reduced to $35,000, which sum

the Board and then the council finally

voted on condition that 350 hands

be worked ten months a year for ten

years.13

The Board's work was far from over,

however, because Judge

Charles Follett and engine manufacturer

Julius J. D. McNamar filed

suit to stop the whole bond issue. For

weeks Board representatives

interceded with these men to withdraw

their action. If only they would

do so, Judge Hunter assured a packed

house at the Music Hall in

April 1891, "there was not another

man in the city who would exercise

his legal right to bring injunction

proceedings as to the constitutional-

ity of the enabling act." American

editor Lyon also joined the effort,

arguing that "we should have the

constitutional right as a city to tax

ourselves as we see fit." But

neither Lyon, nor Hunter, nor anyone

else could shake the stubborn McNamar.

The municipal-aid scheme

simply collapsed before the challenge.14

At this critical juncture some Board

members tried to resurrect the

Industrial Aid Society, but Everett

thought so little of that possibility

that he went ahead privately with his

reconstruction. Others turned to

what proved to be a successful project,

location of the state encamp-

ment for the National Guard in West

Newark. By the spring of 1894,

12. Ibid., March 6, April 24,

June 12, 1890.

13. Brister, Centennial History, I,

524; Advocate, February 12, March 12, 1891.

14. Ibid., March 19, April 23,

1891. In his account of the Board's history (see Advo-

cate, January 2, 1913), Charles C. Metz states that "an

attempt made by a few manu-

factories already located here to take

advantage of this appropriation to secure for them-

selves this financial aid . . . arrayed an opposition to the whole scheme"; personal

hostility toward Everett may have been

involved here.

Town Promotion in Newark 259

using the familiar subscription method,

the Board of Trade had raised

$2,700 of the $5,000 needed to bring

Newark Machine back from

Columbus.15

No local leader came up with a promising

plan for attracting new in-

dustry before W. H. Parrish, once a

Pennsylvania agent at Newark, ap-

proached his former colleagues on the

Board of Trade in September

1894. A tin plate company would build

"a Four Mill Tin Plate plant

with Bar Mill, the same to employ not

less than 250 people," on condi-

tion that Newark citizens "buy from

them 400 town lots, at an average

price of $250 per lot," from the

100-acre farm north of the Panhandle

tracks in East Newark, upon which

Parrish had just taken an option.

Payments could be made in installments

of "20 per cent down and 10

per cent per month until the lot is paid

for," Parrish indicated. A trus-

tee would make scheduled allotments to

the company as building

progressed, the final 20 percent coming

"after works have been in op-

eration 30 days."16

The public greeted the plan with favor.

Investigation of the tin-plate

company directors, moreover, produced a

commercial report that they

were "A-l." Within a month signatures

were secured for 340 lots, and

the remainder probably would have

presented no obstacle if the com-

pany could have handled the further cost

of what reportedly would

have been a $150,000 plant. But as Lyon

later explained, "the tin plate

project . . . failed because the parties

at the head of it were financial-

ly unable" to carry through their

part of the bargain.17

No one regretted this more than the

Pennsylvania's division officers,

who "decided that Newark should not

lose by the failure of the tin

plate, and . . . put forth every effort

to secure a factory that would be

equal in every respect . . . and have an

unquestioned financial stand-

ing." Anxious to build up their

freight business, they wanted some

reliable firm to build upon the ten

acres allotted beside their tracks.

At the suggestion of Parrish's immediate

superior, J. J. Turner, a

Pennsylvania vice president, Major

Augustus H. Heisey of Pittsburgh

soon became interested in locating a

glass factory in Newark.18

The Board of Trade received excellent

references from Pittsburgh

banks and business organizations on

Heisey. And though the chairman

of the Board's investigating committee

at first felt "that the demands

of these people for an equal number of

lots with the tin plate company

15. On the encampment grounds, see Advocate,

August 13, 1891; February 4, March

3, 10, 1892; on Everett, see Ibid., November

17, 1892.

16. W. H. Parrish to Charles C. Metz,

president, Board of Trade, September 21,

1894, printed in Advocate, October

11, 1894.

17. Ibid., September 27, October

11, 18, 1894; April 11, 1895.

18. Kingery, Beginning, 78; Advocate,

April 11, 1895.

260 OHIO

HISTORY

were exorbitant," he changed his

mind after visiting the plant at Wash-

ington, Pennsylvania, operated by

Heisey's brothers-in-law, "an exact

duplicate" of the one proposed for

Newark. "After looking through

this factory and consulting those who

were intimate with the working,"

reported merchant H. H. Griggs, the

Board's chief emissary, "I made

up my mind that the money I had agreed

to invest in the tin plate con-

cern could be better spent in the

securing of a magnificent concern

like this."19

A. H. Heisey applied his own pressure

when he warned in April

1895 that "the people must take

hold or I will drop the matter"; he

was in a position to lease a factory in

Uniontown, he asserted, "and I

must give answer this week, so, unless

the Newark deal looks like a

success, I will take hold of the

latter." Spurred on also by the Board

of Trade and the local press, enough

citizens switched their subscrip-

tions over to the Heisey Land Syndicate

to obtain the factory. Newark

boosters had reason to rejoice. As

production started up the next year,

210 workers were employed in the plant.

The land seemed to have

solved their perennial problem.20

Though the Heisey Land Syndicate never

published a profit-and-loss

statement, the beauty of a

land-financing scheme was readily apparent.

The railroad stood to gain not only from

Heisey traffic, but from any

other industry attracted by the promise

of a free site in the seventeen

acres set aside for that purpose in the

100-acre tract. Heisey acquired

ten acres for location, plus buildings

and equipment from profit on

land sales. A purchaser of one of the

450 lots, at an average price of

$175, obtained a saleable property on

which a workingman's house

could be erected. Workers attracted to

Newark by employment oppor-

tunities could find convenient housing

at reasonable prices. And every

businessman in town anticipated an

expanded trade.

An astute entrepreneur like E. H.

Everett immediately recognized

these advantages. As co-owner of a

100-acre farm just north of the glass

works, Everett indicated that he was

agreeable to the industrial ex-

pansion that "a good many people of

Newark" seemed to desire. "If

the people are willing to buy at an

average price of $350, three hundred

lots into which the Hoskinson farm might

be divided," he told an Ad-

vocate reporter, "I would agree to establish a window

glass factory on

19. Brister, Centennial History, II,

103; Advocate, April 18, 1895.

20. A. H. Heisey to W. H. Parrish, April

15, 1895, printed in Advocate, April 18, 1895;

Ibid., August 8, 1895; American, June 16, 1896; Advocate,

January 3, 1900. Heisey's

contract with W. H. Parrish and J. J.

Turner provided that after he was reimbursed for

the $25,000 he paid for the Penney

property and also received $30,000 as a bonus for

putting up the plant, the residue would

be divided among the three parties; the lots

failed to sell well enough to pay the

$30,000, so there was subsequent legal controversy

over how the remaining lots should be

divided; see Advocate, June 5, 1900.

|

Town Promotion in Newark 261 |

|

|

|

one corner of that strip of land that would employ at the start not less than 200 men."21 With the Heisey syndicate absorbing so much local capital, however, and with Newark showing the effects of the nationwide depression in spring of 1895, there was not the demand for another land-financed project. In fact the syndicate itself had no luck the following December with a more modest proposal, to bring in a "large manufacturing in- dustry" employing not less than fifty men "if the citizens of Newark will take twenty lots, at an average price of $175." Traffic and employ- ment were down sharply for the B.&O., which finally went into re- ceivership in August 1896. That same year the Newark street railway defaulted also, and columns of the local papers were filled with sher- iff's sales. Indeed, for three years the Board of Trade did not even meet. Hard times had really come.22

21. Ibid., April 18, 1895. 22. Ibid., November 29, 1895; American, April 10, June 5, August 6, 1896. |

262 OHIO HISTORY

The situation began to improve slowly.

By 1899 the B.&O. shops

were employing six hundred men six days

a week, tripling the 1893-

1896 payroll. The booster spirit revived

as well. "All about us are

cities working for their own

advancement," the Republican American

Tribune observed in July 1899; "Zanesville and Coshocton

on the east

and Columbus on the west are offering

sites, buildings, and bonuses

while Newark sits still and sucks its

thumb in quiet complacency."

The old Board of Trade was

"defunct," declared the editor. "Let us be

up and doing."23

Within a month the Board was meeting to

consider a report by the

Pennsylvania's W. H. Parrish on the

Jewett Car Company, manufac-

turer of the Newark electric railway's

new cars, which was contempla-

ting a move from the small town of

Jewett in eastern Ohio. By Septem-

ber this firm was ready to come to

Newark if it could obtain a free site,

a 50- x 250-foot building, and the cost

of transferring its shop. Total

cost to the Board of Trade would be

$8,000. On its part Jewett agreed

to employ an average of not less than

one hundred men a day for ten

months a year for five years. In

surprisingly short order, the deal was

made and the Board of Trade had raised

the $8,000 needed.24

That such a sum could be subscribed in

little more than a month's

time revealed the fresh confidence the

return of prosperity brought the

city's prospects. Following a

reorganization meeting in December 1899,

the Board enthusiastically reelected

lumber dealer W. H. Smith pres-

ident and set a five dollar fee for

membership. In April 1900 it under-

took to raise $2,500 to bring in another

firm, the E. T. Rugg Company,

maker of rope and halters in the small

town of Alexandria, ten miles

to the west.25

With five employees, E. T. Rugg had

started his factory ten years

before and had built it into a firm

employing sixty-five (mostly women

at $1-$2.50 per day) turning out 8,000

halters daily. Like Jewett, Ohio,

the village of Alexandria had a limited

labor pool and inferior trans-

port facilities, so Rugg sought a better

place in which to expand. He

found an unused foundry alongside the

B.&O. tracks, the Board of Trade

23. Newark American Tribune, September

7, 14, 21, October 28, November 30, De-

cember 7, 1899. On the Coshocton Board

of Trade, organized in 1899, see William J.

Bahmer, Centennial History of

Coshocton County, O., I (Chicago, 1909), 216-17. On the

Zanesville Board, first organized in

1868 to promote "the city of natural advantages," see

Norris F. Schneider, Y Bridge City:

The Story of Zanesville and Muskingum County,

Ohio (Cleveland, 1950), 232ff., and Thomas W. Lewis, Zanesville

and Muskingum Co.,

Ohio (3 vols., Chicago, 1927).

24. American Tribune, September

7, 14, 21, October 28, November 30, December 7,

1899. The Board of Trade obtained some

portion of the $8,000 from lot sales on the

thirty-two acres adjoining the five-acre

site set aside for Jewett Car; see American Tri-

bune, October 28, 1899.

25. Advocate, January 2, 1913; American,

January 10, 1900.

Town Promotion in Newark 263

put together the $2,500 needed, and by

July 1900 there were twenty-

five workers on three looms producing

over 7,000 feet of webbing a day

at the new plant.26

"The Board of Trade does not

propose to stop with the excellent

work that has been done, neither does it

want to impose any hardships

on the men who have generously helped in

capturing the two industries

just mentioned," the Advocate announced

in printing the list of con-

tributors to the Rugg subscription,

"but it feels that there is just one

more thing to do this spring and that is

by the sale of a few very de-

sirable lots put fully 400 more people

to work in this city." It was a

propitious time indeed for the

land-financing method, for the influx

of workers at Jewett and Rugg and the

boom in production at Moser,

Wehrle and Everett Glass were already

straining the housing market.

If the lots were carved out of Everett's

land north of his plant, more-

over, as the Board agreed should be

done, then they would help to pay

for the addition of a ten-ring tank to

the five continuous tanks in-

stalled there since 1890. Once again the

land would serve several pur-

poses.27 More than half the 250 lots in

Everett's "Riverside Addition"

were purchased for $250 each by August

1900; in turn E. H. Everett

began the expansion that eventually made

it the largest glass-bottle

plant in the nation.28

Of course, land-financing was not unique

to Newark. In neighbor-

ing Zanesville, for example, the Board

of Trade used all the methods of

fund-raising of the Newark organization.

In 1891 J. B. Owens had

transferred his tile factory from

Roseville with the encouragement of a

free site and $2,500 in moving expenses.

In 1892 American Encaustic

Tiling Company built a larger plant

there with the aid of a $40,000

bond issue. In 1894 Kearns Gorsuch and

Company received $30,000

from the Zanesville Board to reorganize

its glass operations. And after

an unsuccessful attempt at a lot sale in

1899, the Citizens' League in

November 1900 resolved to try that

method again, to raise a bonus of

$30,000 for a Dresden (Ohio) firm to

construct a steel mill in the Y

Bridge City.29

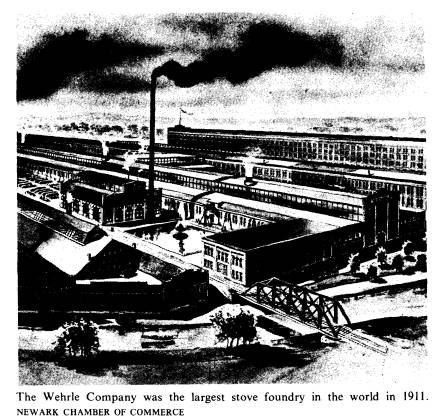

A manufactory such as Newark's Moser-Wehrle,

on the other hand,

was reluctant to resort to

Board-assisted financing of any sort. The

guiding genius of this firm's expansion

from a small East End foundry

to the nation's largest stove

manufacturer was William W. Wehrle,

26. Ibid., April 21, 1900; Advocate,

May 6, May 24, July 5, 1900.

27. Ibid., May 24, 1900; American,

February 3, 1900.

28. Brister, Centennial History, I,

524; Advocate, August 23, 1900; C. H. Spencer,

"Industrial Newark," The

Ohio Magazine, III (July 1907), 47-48.

29. Schneider, Y Bridge City, 260-62;

Advocate, November 29, 1900. Coschocton also

used lot sales; see Bahmer, Centennial

History, 216-17; Advocate, December 13, 1901.

264 OHIO HISTORY

who with his brother August had assumed

active direction after their

father's death in 1890. A truly rugged

individualist who kept his own

counsel, Will Wehrle relocated in West

Newark, eased out former

partner John Moser, and in December 1900

launched a building pro-

gram that lifted employment from 225 to

over 600 workmen. By June

1901 the Wehrle factory was fourth in

size among American stove and

range manufacturers, equipped to turn

out 75,000 units annually.30

Still demand increased, especially as

the rapidly developing Sears,

Roebuck and Company of Chicago began to

take more and more of the

Wehrle products, so that by 1902-1903

Will Wehrle saw need to en-

large further. This time he did turn to

the Board of Trade, forty members

of which pledged "to give at least

one day" to selling "200 lots at an

average price of $250 each" in West

Newark for the benefit of Wehrle

and the much smaller James E. Thomas

foundry. By January 1903

these volunteers had sold over 250

parcels in the "Wehrle Addition,"

at 20 percent down and 10 percent a

month, and though some pay-

ments lagged, the companies proceeded

with construction. By 1905

the Wehrle monthly payroll of $75,000

reportedly ranked second in

Newark only to the B.&O.'s

$120,000.31

The Wehrle project was nevertheless the

Board of Trade's last ven-

ture in land-financing. Some Board

members questioned privately

whether the Wehrle promotion had been

worth their time and effort,

since he would have had to expand

anyway. Moreover, officials were

beginning to be more cautious about

accepting such additions to the

city; before council finally passed it

over his veto, the mayor twice

turned down the ordinance on the Wehrle

addition, on the grounds

that the grading and streets were not in

proper condition. Then, too,

the land available for workingmen's

homes close by the factories was

no longer so plentiful, whereas real

estate men sought other sites to

develop for their own profit.32

Local boosters were too busy exulting at

Newark's growth to mind

these changes. At annual meetings of the

Board of Trade in 1903 and

1904, speakers loosed a flood of

panegyric over expansion of Wehrle

and Everett Glass, discovery of new gas

fields in the county, connec-

tion by interurban with Zanesville as

well as Columbus, lack of "loaf-

ers and idle men," prevalence of

good schools and good health.

"Newark, therefore, is a good place

to live in," concluded the Rev-

erend J. C. Schindel, and "it has a

great future-before us stands the

30. Brister, Centennial History, I,

524; Spencer, "Industrial Newark," 45-47; Ameri-

can Tribune, April 6, 1899; Advocate, December 27, 1900, June

7, 1901, June 6, 1905.

31. Advocate, January 20, 1903,

March 24, 1905.

32. Ibid., February 6, October

23, November 20, December 25, 1903.

Town Promotion in Newark 265

possibility and you have it in your

hands to make it what we all hope

to see."33

Amid the chorus of congratulation came

notes of warning, however.

The interurban brought shoppers to

Newark, but it took them to Co-

lumbus as well. And the merchants of

Ohio's burgeoning capital city

were advertising their wares more

aggressively. "When you have a

dollar or two to spend, spend it in

Newark," asserted the Advocate in

an otherwise optimistic article in July

1903; "the stores here are equal

to those in surrounding cities and the

values are as good, if not better."

"If you spend a dollar here you may

get a piece of it back sometime,"

the Advocate added, in what would

become a recurrent refrain, "but

if it goes to another city you may as

well say good bye forever." Came

the clincher: "We need the money,

so keep it in town as far as pos-

sible."34

A more ominous note sounded in the wake

of the $100,000 fire that

destroyed the Wehrle steel shop in 1904,

throwing 1,000 men out of

work. The company rebuilt upon a larger

scale and even diversified

operations by buying out Atlas Safe at

Fostoria and moving the equip-

ment to Newark, yet Will Wehrle

complained about the inadequate

fire protection in the West End. "I

don't intend to do anything more

for the city of Newark," he told a

reporter in April 1905. "Any new

building I have to put up, other than

those necessary to handle the out-

put of our present industry, will be

erected outside of Newark,"

Wehrle asserted. "We are way out

here from the city and have prac-

tically no fire protection."35

Newark's water situation was just then

so confused by the transfer

from private to municipal ownership that

the Board of Trade finally

got up a special subscription of $3,600

to supply a new fire main out to

the Wehrle plant. That emergency action

must have impressed the

Wehrle brothers favorably, for within

two years they were adding two

cupolas to the four in operation,

lifting capacity to 900 stoves a day

and employment to almost 2,000 workers.

Though they did open up a

subsidiary at Coshocton, forty miles to

the northeast, the bulk of pro-

duction remained at the Newark plant,

which with twenty acres under

roof was popularly billed as "the

largest stove foundry in the world."36

The expansion of Everett Glass also

seemed to counter any pessimism

33. Ibid., February 6, 1903;

February 23, 1904.

34. Ibid., July 31, 1903.

Columbus had grown even faster than Newark, from 51,647

in 1880 to 125,560 in 1900; after 1900

Newark papers carried more advertising by

Columbus firms, particularly in the

Christmas season.

35. Advocate, April 18, 1905.

36. Ibid., August 1, 4, 8, 1905;

April 7, June 7, July 30, August 2, 1907; see artist's

sketch of the Wehrle Company in the

sixty-four-page pamphlet issued by the Newark

Board of Trade in 1911, at Licking

County Historical Society, Newark, Ohio.

266 OHIO

HISTORY

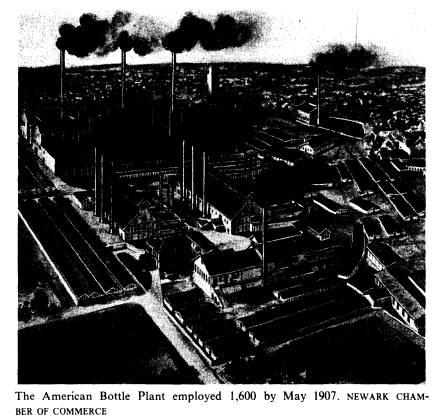

among boosters. In 1904 Everett

incorporated his factory into a new

$4,000,000 concern, the Ohio Bottle

Company (of Newark), which also

absorbed glass-making facilities at

Massillon and Wooster. The next

year Ohio Bottle sold some of its land

in the North End to Everett's

newly incorporated Newark Machine

Bottle, which would install the

revolutionary Owens machine, capable of

turning out "14 perfectly

formed bottles a minute." And in

August 1905 Ohio Bottle and Ne-

wark Machine Bottle merged into another

corporate creation, the

American Bottle Company, capitalized at

$10,000,000, to include "all

the plants heretofore the property of

the Adolphus Busch Manufac-

turing Company of St. Louis, Mo."

at Streator and Belleville, Illinois.

By May 1907, employing fifteen machines

and 1,600 workmen, Amer-

ican Bottle at Newark shipped a record

412 car loads of glassware

a month; with six more tanks scheduled

to start up the next fall, it too

would be one of the greatest plants of

its kind in the world. With

stove and now bottle production tied

into a national market, the New-

ark economy was more integrated into the

emerging urban-industrial

system.37

While American Bottle and Wehrle Stove

were capitalizing upon

national marketing and advanced

technology, however, the Board of

Trade was having troubles elsewhere. For

one thing, the Newark

Fuel and Gas Company was raising prices.

That did not bother Ever-

ett or Wehrle or Heisey, for they piped

in their own gas from their

own wells out in the county. It did

bother the Board leaders, for in

1906 they "had a glass factory on

the string, but nine cent gas was

too high, and another iron industry

seeking a location was discour-

aged by the same fact." When Heisey

indicated the next year that

"any industry locating outside the

city limits could get gas from his

mains at seven cents per thousand

feet," the Board president was un-

derstandably pleased. "Cheap fuel

is better than a bonus, lot sales and

money contributions to offer factories

that are seeking a location,"

President F. M. Black asserted. "It

is something substantial, and we

have lots of it to offer."38

37. Advocate, August 5, 12, 1904;

May 9, August 25, 1905; May 17, 1907. The

Board's brochure of 1911 has a similar

sketch of American Bottle. In 1905 Heisey Glass

also doubled its capacity; Spencer,

"Industrial Newark," 50. Michael J. Owens developed

his machine at Newark in 1899; see John

M. Weed, "Business as Usual," in Harlow

Lindley, comp., Ohio in the Twentieth

Century, 1900-1938, vol. VI of Wittke, History of

Ohio, 178.

38. Advocate, April 5, 1907; see

also Black's article, "Natural Gas in Licking

County," The Ohio Magazine, III

(July 1907), 56-60. Zanesville industry was having

similar problems with Ohio Fuel Supply

Company; Advocate, August 24, 1906. At the

same time Zanesville was increasingly

worried over why it had not grown since 1900; see

the Zanesville Signal, cited in

the Advocate, March 28, 1905, as well as Schneider, Y

Bridge City, 293.

Town Promotion in Newark 267

At the same time Black admitted that

traditional fund-raising meth-

ods were not working well. Newark

businessmen "were either getting

tired of contributing to the Board of

Trade and lot sales," he stated

at the Board's annual banquet in 1907,

"or were tired of being called

upon by the same old members of the

board." He recommended that

Newark follow the Columbus Board's

example and hire a secretary

who would "do all the

correspondence work and seek the new indus-

tries which are solicited to locate in

the city." One member objected

that a professional secretary would be

too expensive, but the general

sentiment was that without some such officer,

the directors "would di-

vide their time and attention between

their own respective interests

and those of the board and as a result,

neither would receive the proper

attention."39

Discouragement over Board efforts had

arisen out of its year-long

struggle to reactivate the West End

plant which Weldless Tube and

then Newark Iron and Steel had operated

without much success since

1896. The Board directors had finally

found a Pittsburgh company

willing to turn it into a mill to

re-roll steel rails; they had also dunned

members for their part of the required

payment of $8,000. But active

businessmen were more reluctant than

they once had been to devote

many hours to such a project. Since

Boards of Trade not only in

Columbus but in Detroit and other cities

were successfully using spe-

cialists, it seemed wise to hire as

secretary J. M. Maylone, one of

Newark's longtime boosters. The Board

opened an office on the top

floor of Newark Trust's new ten-story

"skyscraper," and started a

drive for five hundred members to pay

the added costs.40

No sooner had Maylone begun the

membership canvass than the

economy slumped following the Panic of

1907. He stayed on for two

years before taking a cashier's job at

Coshocton, but did not attract

any new industries. The one major

accomplishment of this depressed

period was to bring the 1909 G.A.R.

summer encampment to Newark's

"Permanent Encampment" site.41

Through the influence of Maylone's

successor, I. M. Phillips, and the offer

of a free site and bonus pay-

ment, the Board did induce a Columbus

shoe company to expand its

small local shop into a three-story

factory in the West End. Yet New-

39. Advocate, April 5, 1907.

Columbus had had a secretary since 1884; see Hooper,

History of Columbus, 264.

40. Actually only $5,000 was raised for

the rolling mill, and as late as 1912 only $3,090

of that was paid in; see Newark Board of

Trade, "Confidential Bulletin," I (April 6,

1912), in "Old Board of Trade"

file, Newark Chamber of Commerce. See also Advocate,

December 11, 1906; February 12, August

30, 1907.

41. Ibid., February 6, March 6,

June 4, 25, 1908; May 13, October 21, 1909. This site

had just been deeded back to the Board

of Trade since the National Guard no longer

needed it.

|

268 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

ark merchants were so distressed at the general inactivity of the Board that they formed another body, the Business Men's Association, to hold regular monthly dinner meetings through the winter of 1909- 1910. The Board of Trade's directors provoked further dispute by pro- posing in April 1910 to lease the encampment grounds for $650 a year to a private group for a country club; dissent only subsided upon agreement that the contract might be terminated at any time upon a year's notice.42 It was at this crucial point in the Board's trials that the prohibition struggle violently intervened. Some kind of confrontation had been building ever since the county dry forces defeated Newark's wet ma- jority in the 1908 election under Ohio's county-option law. As saloons

42. A few records of the Business Men's Association, including a letter from W. H. Mazey to Frank L. Beggs, March 28, 1910, illustrating the hard feelings of the time, are in "Old Board of Trade" file, Newark Chamber of Commerce. See also Advocate, May 27, July 22, December 9, 1909; February 17, April 14, 1910. |

Town Promotion in Newark

269

closed and license revenues declined,

the ranks of the anti-prohibition-

ists grew stronger. At the same time

continued violations and weak

enforcement exasperated the anti-saloon

leaders, who began to employ

"dry detectives" armed with

special warrants to uncover illegal opera-

tions. On July 8, 1910, one of these

out-of-town investigators fatally

wounded a saloonkeeper following a

Newark raid. In retribution an

unruly crowd broke into the jail, took

off with the accused, and strung

him up on the public square.43

Aghast, alarmed, ashamed, Board of Trade

members rallied behind

their president, Advocate officer

C. H. Spencer, whose paper proclaimed

"NEWARK MUST CLEAN HOUSE."

"Today this city stands in dis-

grace and has made proud Ohio hang its

head in abject shame," the

Advocate declared. "It now remains for Newark to show the

world the

real stuff of which she is made by

making amends so far as is possible

for the heinous tragedy which has been

enacted."44

While public authorities removed

delinquent officials and began to

prosecute those charged with the crime,

the Board of Trade launched

a determined drive to overcome its latest

handicap. It mended the

breach with the Business Men's

Association and signed up over six

hundred members, far more than had ever

joined before. It sponsored

the city's first Clean Up Day and Arbor

Day, raised subscriptions for

the library fund and the Court House

Park Improvement, promoted

the hospital, the Y.W.C.A. and the Good

Roads Movement. It care-

fully investigated the "Direct

Drive" patented by F. M. Blair of Cin-

cinnati and then secured backers to

finance constructions of a two-ton

four-cylinder auto truck equipped with

this novel transmission. All

this the Board accomplished within a

year of the tragedy.45

43. Ray Stannard Baker gives colorful

background in "This Crust of Civilization: A

Study of the Liquor Traffic in Newark,

Ohio," American Magazine, LXXI (April 1911),

691-704, as does Sloane Gordon in

"Booze, Boodle and Bloodshed in the Middle West,"

Cosmopolitan Magazine, XLIX (November 1910), 761-775; see also Advocate, January

7, 21, March 4, 11, 18, May 20, 27, July

8, August 12, 1909; March 24, June 9, 1910.

44. James Lee Burke, "The Public

Career of Judson Harmon" (Ph.D. dissertation,

The Ohio State University, 1969),

216-21; Advocate, July 14, 1910. Governor Harmon

suspended Newark's mayor and Licking

County's sheriff, who then resigned. Augustus

Raymond Hatton argued that "the

Newark affair" was unusual, "an exceptional case

in which many elements combined to lead

to disastrous results"; see "The Liquor

Situation in Ohio," Proceedings

. . . of the National Municipal League (n.p., 1910),

395-422.

45. Edward Kibler to the Board of

Governors of the "Newark Club," January 11, 1910,

in "Old Board of Trade" file,

Newark Chamber of Commerce, shows earlier concern

about reuniting the Board and the

Business Men's Association; the Advocate, January

19, February 23, March 30, April 13, 27,

May 18, 1911, followed the Board's activities

closely. Chalmers L. Pancoast made the

"Solid Foundation Work" of the Newark Board

of Trade his theme for "Record in a

6 Months Campaign," Town Development, IV

(June 1911).

270 OHIO

HISTORY

By 1912 the Board leaders were advancing

so many schemes for

civic improvement that at least one

member objected, arguing that

"a half dozen or more of the

suggestions accomplished would be

better than fewer half done." Yet

another member was disappointed

that among thirty areas for action the

program committee included

construction of a workhouse and a

convention hall but ignored the

disgraceful condition of the city hall,

where there was "a difference of

nearly 12 inches in the floor from one

side of the room to the other."

In its zeal for municipal improvement

the Board did not entirely

forsake acquisition of new factories,

yet the search for such oppor-

tunities was less active, the concern

for beautification and boosting

more apparent.46

Civic improvement on the "City

Beautiful" model was a common

urban aspiration of the Progressive era,

but communities such as New-

ark lacked the financial resources to

accomplish much. Boosting

through Board of Trade signs and

stickers proclaiming "A Busy Factory

Town Welcomes You" and "Boost

Newark" was easier and less ex-

pensive. "The boosting spirit which

has developed in Newark is the

kind of a spirit which will make a

successful city," declared urban

publicist Chalmers L. Pancoast, an

ex-Newarkite whom the Board paid

to do some advertising for its

membership campaign. "It is the 'do

something' spirit which reinfuses red

bood in the deadest town in

existence," he added, "the

spirit which will attract the attention of the

outside world and make investors and

promoters investigate a

town's possibilities."47

To attract new industry remained the

ultimate goal of Board of

Trade members. As memory of the lynching

faded, moreover, there

was less concern generally about the

city's image. Fourteen of the

twenty-six men indicted for complicity

in the tragedy had been con-

victed; prohibition had been repealed in

Newark under local option;

the laws were being more strictly

enforced in what had been "one of

the most pronouncedly 'wide-open' of the

smaller cities of the state."

46. C. H. Spencer, president, "A

Personal Letter to 614 Members, Newark Board of

Trade," February 10, 1911, in

"Old Board of Trade" file, Newark Chamber of Com-

merce; Advocate, March 7, 1912.

Article after article in American City demonstrated

that it was the popular thing to broaden

Board of Trade activities in these years; see

e.g., Richard B. Watrous, "The

Responsibilities of Commercial Organizations in Fur-

thering the Adoption of City Plans"

(May 1910) and Logan McKee, "Civic Work of the

Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce"

(July 1911). "Clean up days" were becoming "the

vogue" in the "Central

West," said American City, III (November 1910), 255.

47. Newark Board of Trade,

"Confidential Bulletin," I (April 6, 1912), 3-4; Advocate,

January 18, May 16, 1912; June 12, 1913.

For an example of Pancoast's work, see

Advocate, February 16, 1913. On the "City Beautiful"

movement, see Mel Scott, Ameri-

can City Planning Since 1890 (Berkeley, 1969), 26-71.

Town Promotion in Newark 271

It was time to do more to bring in

factories, argued a majority of the

directors, and the place to begin was by

replacing Phillips' amiable

successor, retired merchant tailor

William C. Wells, with a real exec-

utive secretary who would work more

aggressively. In October 1913,

over three years after the lynching, W.

C. Wakefield took over as the

Board's new "Business

Manager."48

Fresh from organizing Lancaster, Ohio's,

Chamber of Commerce,

Wakefield at once indicated that he

would not pursue civic improve-

ments: "The business of a trade

body is TRADE, not morals, politics,

legislation, reforms, but pure and

unadulterated TRADE." In his brief

time in the city he had found that the

Board was "not a popular orga-

nization," that there was "no

unity of purpose among its members," he

told the first general meeting in

October 1913. What was needed was

an objective to be pursued

"relentlessly," and for Wakefield the

"prime object" must be

"to encourage industry, this by securing new

industries."49

To take such a strong stand in such an

indiscreet manner did not

contribute to unity of purpose: it only

underlined the divisions within

the organization. Within weeks of his

appointment the retail-store

owners revived their renamed Merchants'

Association. Within months

the Board's campaign for a new factory

fund encountered much oppo-

sition. Within a year Wakefield himself

was gone, victim of the "worst

season of criticism" that the Board

of Trade "has ever suffered."50

Though often tactless, Wakefield's

failure resulted mainly from con-

ditions over which neither he nor the

Board of Trade had much control.

His fund campaign was well organized,

but many spare dollars had

already gone into the recent

construction of three large churches and

the Masonic Temple. In the spring of

1914 the local economy was

also in the same slump that was

troubling the nation. As late as Febru-

ary 1915 "it was not thought

advisable to solicit funds for Belgium

relief work in a direct way"

because of "the present financial condition

of Newark."51

The financial pinch also affected Board

efforts to assist Blair Truck.

That company had used the $36,000 from

its initial stock subscription

48. Outlook, C (January 6, 1912),

7-8; Newark Board of Trade, "Confidential Bulle-

tin," I (April 6, 1912), 1-2; Columbus

Dispatch, January 26, 1913; Advocate, October 30,

1913. On Wells, see Brister, Centennial

History, II, 592-93.

49. Advocate, November 20, 1913.

50. In addition to the factory fund,

Wakefield had suggested new election procedures,

stricter rules on attendance, and a

weekly publication called "Ginger Snap" to keep

members "alive to 'what's doing'

"-"An entirely new order of things" was coming, said

the Advocate. See November 6,

1913; January 24, March 12, April 2, December 17,

1914.

51. Ibid., April 16, 1914;

February 17, 1915.

272 OHIO HISTORY

to take over part of the Newark Machine

property and start up produc-

tion. The increase in orders attendant

upon the outbreak of war in

Europe created a crisis: would Newark

citizens invest at least $64,000

more to convert the whole plant into a

larger, more efficient operation,

or would it be necessary to bring in

outside capital which might re-

move the plant to another city?

Encouraged by the Newark Lumber of-

ficial who disposed of his business

interests to put $20,000 into Blair

and become its new sales manager, a mass

meeting of "former mem-

bers of the Newark Board of Trade"

agreed in December 1914 to "Try

to Keep Plant in Newark." But hard

times conspired with the Board's

enfeebled state to inhibit stock sales.

Finally an investment firm in

Hamilton, Ohio, contracted in February

1915 to finance the expansion:

for a while Blair Truck was saved for

Newark.52

The "reunion" meetings of the

old Board encouraged local boosters

to look beyond their difficult season

with Wakefield. Indeed, the need to

promote the "greater Newark"

first projected in 1907 seemed more

urgent than ever. Competition among

cities was becoming keener, and

some Ohio communities were rapidly

expanding, but Newark appeared

to be standing still, if not actually

declining. Soon one leading lawyer

was admitting that "Newark six

years ago was as far advanced indus-

trially as it is now." Another pointed

to lower school enrollments and

more vacant houses to show "beyond

a doubt that the population of

Newark is falling off." After three

decades of better than average

growth, the town was falling behind.53

Factors more basic than the lynching or

any failing of the Board of

Trade accounted for this decline.

Shortage of natural gas had already

forced so many residents to switch to

coal that Newark was becoming

a "two-collar-a-day town."

Prohibition laws cut production at Ameri-

can Bottle; autos and buses reduced

demand for Rugg halters and

Jewett interurban cars. E. H. Everett

and other capable entrepreneurs

left for busier centers and grander

projects; the Wehrles interested them-

selves in Catholic causes in Columbus

rather than in Newark institu-

tions. Competition and regulation hurt

the railroads, for so long the

city's mainstay, whereas Blair Truck and

Pharis Tire and Rubber were

far from strong entries in the race for

automotive dominance. As the

whole American economy shifted away from

local business and in-

dustry toward regional markets and

national corporations, major

centers such as Cleveland or Columbus

profitted at Newark's ex-

pense.54

52. Ibid., April 27, September

17, 1911; January 18, 1912; September 13, December

17, 1914; February 24, 1915

53. Ibid., April 23, 1907; April 8, 18, 1916.

54. Ibid., January 14, November 19, 1914; January 11, 1915

(natural gas); June 18,

Town Promotion in Newark 273

The conventional wisdom among boosters,

on the other hand, tended

to ignore such handicaps: it relied

instead on the "many authorities

who say that the growth of cities is in

direct proportion to the efficiency

of

their commercial organizations." As

competitive pressures

mounted, the more informal and

amateurish efforts of the past would

have to go, argued newly-established national

periodicals such as

American City and Town Development: if a modern board of trade

or

chamber of commerce was to be effective,

it would need a trained sec-

retary employing expert methods. In

fact, the founding in 1909 of these

specialized journals indicated how

widespread were the difficulties that

Newark promoters were experiencing, how

general was the demand

for more efficient operations.55

Many Newark boosters agreed with the

conventional wisdom: the

trouble with their town was that it had

been "backward in organizing

its commercial forces for city-building

purposes." The old Board of

Trade had been "doing the best they

could with nothing to work with";

they had "always been poor and a

subject of charity"; "like all insol-

vents" they had been "subject

of the kicks and scorn of the business

world." The remedy was obvious.

"We want a Chamber of Commerce

that we can all be proud of, with money

sufficient to its needs, with an

expert and efficient secretary, a

trained man, and then you will see the

old town go along some."56

In April 1916, their ears ringing with

such sentiments, three hundred

Newark businessmen transformed the old

Board of Trade into a new

Chamber of Commerce with which the

Merchants' Association would

affiliate. In so doing they did not

dwell upon the city's "natural advan-

tages," nor did they publicize the

fact that Town Development Inc. of

New York, publisher of Town

Development and paid consultant on

promotions of this type, had been hired

to manage a "whirlwind cam-

paign" for members of the new

Chamber. Many American cities had

successfully revived their trade bodies

in this fashion, yet the whole

"Forward Newark Movement"

mounted by outside professionals had a

merchandising flavor that suggested a

lack of substance. It suggested

1914 (American Bottle); June 22, 1911

(Everett); August 25, 1910 (Wehrle); October 1,

December 24, 1914 (railroads).

55. Ibid., April 18, 1916. An excellent example of the

"conventional wisdom" is Ryer-

son Ritchie, "The Modern Chamber of

Commerce," National Municipal Review, I

(April 1912), 2, 161-69; in comparing

Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Buffalo, and Cin-

cinnati in their relative growth in

population between 1890 and 1910, he contended that

their standing was "in exact line

with the relative efficiency of their respective organiza-

tions" and that "Cleveland and

Detroit won the race over their rivals because they had

the advantage of united, vigorous, well

directed effort." See also Harold M. Weir, "Growth

of Population of Cities," Town

Development, III (September 1910).

56. Advocate, April 18, 1916.

274 OHIO

HISTORY

that the new Chamber, though better

financed and more efficiently

managed, would be no more effective than

the old Board in sustaining

Newark's growth.57

Board reorganization could not dispose

of the basic factors, eco-

nomic and social, which since 1907 had

increasingly impeded the

town's industrial development. Nor did

reorganization improve New-

ark's competitive position for war

orders, the bulk of which in Ohio

went to major firms in larger centers

such as Cleveland and Dayton.

The 1920 census told the story: from

1910 to 1920 the population of

Newark increased by only 5.2 percent,

the smallest gain in any Ohio

city of 25,000 or over, whereas the

nation as a whole went up 14.9 per-

cent and its urban territory 25.7

percent. Though Newark's rate of

growth would recover after 1920, it

would still not match the national

average, nor would it ever again

approach the advances made in the

period 1880-1910, when the old Board of

Trade was operative.58

In retrospect, no simple calculus can

gauge the Board's contribution

to Newark's growth. It is obvious that

"natural advantages" and good

transport facilities and a few

enterprising manufacturers were essen-

tial ingredients. It is apparent also

that the lack of local capital to at-

tract or develop industry represented

the main obstacle, though an in-

genious method of land-sale financing

temporarily helped to meet that

challenge. For more than a decade Newark

promoters moved success-

fully toward the goal that seemed to

animate every comparable com-

munity across Ohio and the Midwest in

these imperial years-a larger

and therefore "greater" city.

The lynching gave a unique impetus to

that effort. It also turned it in

57. Minutes, Board of Directors, Newark

Chamber of Commerce, May 4, 1916; F. L.

Beggs to Secretary, Harrisburg Chamber

of Commerce, May 29, 1916; A. H. Heisey to

F. L. Beggs, June 1, 1916; Beggs to

Heisey, June 2, 1916; Newark Chamber of Commerce

file, 1916. In August Beggs announced

that Town Development Company received 25

percent of the first year's fees

collected in the membership drive; the membership fee

was $75 for a three-year subscription,

and 555 members had been signed up in a week's

time in April; see Advocate, April

27, August 17, 1916. Town Development, XVII (June

1916), described the Company's Newark

campaign in D. H. McFarland, "A Notable

Civic Awakening"; similar drives

prior to March 1916 were conducted in fourteen cities

under 25,000, seven from 25,000 to

50,000, seven from 50,000 to 100,000, and ten over

100,000. The American City Bureau in New

York City, educational adjunct of the publi-

cation American City, did

promotional work of this type also; see "The Upbuilding of

Three Organizations," American

City, XI (July 1914), 58-59, and "The Reorganization

of the Syracuse Chamber of

Commerce," X (January 1914), 47-48.

58. E. T. Rugg had a war contract for

halters, and Wehrle for stoves, kettles, and fi-

nally shells, but most of the eleven

plants in Newark engaged in war work had small

jobs received too late in the conflict

to boost manufactures substantially; see Advocate,

September 16, 21, October 4, 30, 1918;

January 13, 1919. From 1910 to 1920 the pop-

ulation of Licking County only went from

55,590 to 56,426 and of Newark from 25,404

to 26,718.

Town Promotion in Newark 275

abrupt and sweeping fashion toward

"civic improvement" as a major

means to promote the city's interests.

But the Newark Board's change

here coincided with a general shift

toward more sophisticated methods

after 1910. Before then small-town

commercial bodies were still concen-

trating primarily upon industrial

acquisition through bonuses or guar-

anty plans or development funds-in

short, through some financial

manipulation. But increasingly

thereafter, influenced in part by the

burgeoning city-planning movement,

attention shifted toward a new

means: the best way to build a city was

by making it a better city in

which to live. Streets, yards, schools,

playgrounds, parks, a hospital-

the list of civic improvements grew

larger and larger. "Community bet-

terment first-factories when

possible," concluded an Indiana poll of

seventeen commercial secretaries.59

Though more restrained in promoting

community betterment after

1913, the Newark Board was typical of

many trade organizations

caught up in these years in spirited

rivalry for industrial expansion. As

the pages of American City and Town

Development amply demon-

strate, its efforts to secure new

industry, to develop more effective

leadership and a more attractive

city, had their counterpart in

community after community across this

country. From the frequency

with which comparable bodies elsewhere

were seeking help from the

new urban specialists who published

these periodicals, it was apparent

that Newark's difficulty at sustaining

growth was a common problem.

What should or could be done about it

was still unclear: here the con-

ventional wisdom confused the real

economic situation. But this Ohio

town well reflected the troubled times

ahead for American's smaller

cities.60

59. D. H. McFarland, "Comprehensive

Commercial Endeavor," Town Development,

XIII (October 1914); on Dayton, Ibid.,

XIV (March 1915); C. T. Boykin, "Why do

Chambers Lack Sustenance," Ibid.,

XVI (February 1916); "Give no Bonuses," Ibid.,

XVII (April 1916).

60. The experience of Newark's Board of

Trade well illustrated the general conten-

tions of J. O. Hardy, secretary of the

Commercial Club of Fargo, North Dakota, in

"Small City and Town

Problems," Ibid., XVI (October 1915).