Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

JAMES LEFFEL: DOUBLE TURBINE WATER WHEEL INVENTOR

by CARL M. BECKER

Though the evolution of steam engines in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was a dramatic advance in the development of prime movers, waterpower mechanisms retained substantial importance in the industrial growth of western Europe and the United States. Indeed, European and American inventors were substantially improving conventional water wheels and developing new kinds of fluid mechanisms. Much of

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 269-270 |

JAMES LEFFEL 201

their work simply manifested a

long-continuing process, but in part it

represented a response to the use of

steam power; for in old industrial

regions lacking mineral fuel for the

generation of steam power, the more

efficient use of water offered some

degree of economic salvation.1 Further

stimulating the invention of water power

devices was the spirited debate,

especially in the United States in the

1830's and 1840's, over the relative

merits of water and steam power.

Whatever the causative factors, water

wheels were noticeably improved, and,

more importantly, a new and excit-

ing kind of waterpower mechanism -- the

water turbine -- was progressively

elaborated.

The subject of much experimentation

during the second half of the

eighteenth century but not ready for

practical use then, water turbines

were, when finally effectively designed

by the 1860's, considerably more

sophisticated and efficient in their use

of water than were ordinary wheels.

Older, conventional wheels -- overshot,

undershot, and breast wheels -- all

generated power through the direct

action or pressure of water on buckets or

floats, without the water moving

relative to the wheels. In contrast, in the tur-

bine, which was encased and fixed to a

vertical or horizontal shaft, water

flowed through ducts or vanes,

developing into velocity energy as impulses

and reactions were set up between the

flowing water and the passages. To put

it in a simpler way, water ran over or

under traditional wheels but through

turbine wheels.2 In utilization of power

received, water turbines could

deliver ninety percent effectiveness

while conventional wheels developed

about seventy-five percent

effectiveness. Moreover, turbines cost less to

install, occupied less space and turned

with greater velocity than did

conventional wheels.3

Relatively complicated, the turbine lent

itself to the development of

various types. Two general types in use

by the 1840's were reaction and

impulse wheels. In reaction turbines,

which were completely filled with

water, water entered the runner under

pressure after a portion of its

energy had been converted into velocity

energy. In impulse turbines, which

had to be partially filled with air,

water entered under atmospheric pres-

sure after all its energy had been

converted into velocity energy.4 A basis

for sub-classification was the direction

of the flowing water. The flow could

be radial at right angles to the axis of

revolution, or it could be axial, that

is parallel to the axis of revolution.

Radial flow could be outward or inward;

axial flow could be downward or upward.5

Though the great European

pioneer in the invention of turbines,

Benoit Fourneyron, worked almost

exclusively with outward flow reaction

turbines, the wheels often used in

Europe were the Jonval axial flow

turbine and the Girard impulse turbine.

The Jonval turbine was particularly

effective where large quantities of

water were available under low or medium

heads, not uncommon charac-

teristics of European streams. The

Girard wheel was especially valuable

for use under conditions created by high

falls with small volumes of water.6

In the United States, the dominant type

of turbine was the inward flow

reaction wheel. Wheels of this type

designed by the New England engineer,

202 OHIO HISTORY

James B. Francis, were quite popular.7

Francis wheels and mixed-flow tur-

bines, a modification of inward flow

wheels, were used with good effect where

immense volumes of water were

discharged.8 Initially inefficient in the use

of part-loads, they were gradually

improved by various American inventors

in the second half of the nineteenth

century.

General American interest in water

turbines, following in the wake of

the European movement, which had been

on-going since the 1750's, first

became pronounced in the 1830's and

1840's. During these decades Francis,

Uriah Boyden and George Kilburn, all

engineers active in New England,

were significantly advancing the theory

and practice of water turbine

technology.9 Other inventors of lesser

note were also at work, ever sanguine

as they dispatched their patent

applications to the United States patent

office. Reflecting their efforts, the

number of patents granted for turbines

was increasing in the period.10 Apparently

none were granted in the 1820's;

but about twenty-five were issued in the

1830's and 1840's, twenty in the

1850's, thirty in the 1860's, and, as

momentum gathered, over a hundred

in the 1870's.11 This interest had

mounted despite and because of the rising

challenge of steam power. Waterpower

adherents, by word and inventive

deed, argued their cause; but especially

after 1840 many factories were turn-

ing to steam power as its advocates, led

particularly by Charles T. James,

marshalled convincing evidence of the

economic superiority of steam.12

Despite this fact, by the 1850's, water

turbines still replaced the old style

wheels in many mills; all the pitch-back

wheels at the Appleton Company

in Lowell, Massachusetts, for example,

had been supplanted by turbines.

Among the water turbine men whose

efforts were stamped with the

imprint of ingenuity was James Leffel, a

foundry operator who embodied

many of the classic qualities of the

nineteenth century inventor: steadfastness

of purpose and effort, resilient energy

and optimism, and drive for technical

perfection and productive efficiency.

Born in 1806 in Botetourt County,

Virginia, Leffel was but a baby when his

parents, John and Catherine Leffel,

moved to the Ohio country.13 The

family settled near Donnel's Creek,

several miles west of the hamlet of Springfield,

Ohio. Here the father erected

a sawmill and gristmill.14 Young

Leffel worked, of course, in the mills,

learning general mill technology and

developing particularly an interest

in water wheels. Indeed, as one source

has it, "the construction of rude

models of water wheels, and their

practical application to some boyish

purpose, constituted almost the sole

pastime of the leisure hours of his

youth."15

Leffel first made practical use of his

knowledge of water wheels as a

"mere boy" when sometime in the

1820's he built a sawmill in which he

installed a wheel of his own design and

construction. Supposedly, the mill

was "the most efficient mill in

that section of the country," and the wheel,

demonstrating the "great care . . .

exercised in admitting the water to it,

at once gave proof of an innate

knowledge of Hydraulics possessed by no

other mechanic in the country, even if

of greater age and experience."16

His success soon gave Leffel a beseeching

clientele: "The complete success

JAMES LEFFEL 203

of the undertaking at once drew the

attention of other mill owners; and,

notwithstanding his youth, he was beset

on all sides to re-model wheels

which were now, in comparison,

considered as inefficient." And Leffel was

a heroic mechanic: "With the tact

natural to him, he soon detected the

errors in their construction; and many a

manufacturer was constrained to

praise that youthful skill which, as if

by magic, transformed his hitherto

insufficient power into a valuable and

abundant one."17

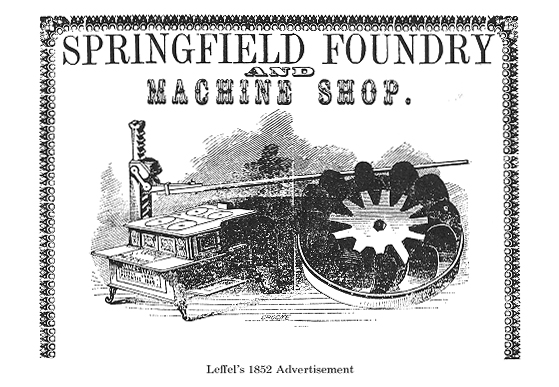

For about fifteen years Leffel worked as

a millwright. Acquiring some

skill in metal working and seeing in the

growing population of Springfield

and Clark County (which rose from 13,114

in 1830 to 16,882 in 1840 and

to 22,178 in 1850) a market for sickles,

knives and other small iron imple-

ments, he decided in the late 1830's to

erect his first foundry and machine

shop near the National Road west of

Springfield near Buck Creek. Com-

pleted in early 1840, the foundry was

the first such facility in the Spring-

field area and was the site of much of

his inventive and innovative labors.18

His initial enterprise in iron enjoyed

success from the beginning. Patronage

became so great by 1843 that he decided

to enlarge his productive capacity

and diversify output. His expansion

plans calling for more capital and

skill than he could muster by himself,

Leffel took on two partners, William

A. John, a molder from Columbus, and T.

Y. Ferrell, a finisher from Cin-

cinnati. Acquiring new flasks and cores

and other equipment, the three

proprietors increased the old line of

small implements and also turned

to the production of mill gearing and

stoves. This new work called for a

more sophisticated casting technology

than did the small implement produc-

tion. Stove manufacturing in particular

demanded the careful casting of

strong and irregular shapes, which in

turn entailed problems of even

shrinkage in cooling. Nevertheless,

stove castings soon accounted for much

of the firm's output; the "Queen of

the West," a typical brand name of the

day, became the first important stove in

the firm's line.19

His partnership with John and Ferrell

was the first of a series of busi-

ness associations that Leffel initiated.

In 1845, after apparently terminating

his connections with the foundrymen, he

entered into a partnership with

William Blackeney, a machinist who gave

him invaluable support for

nearly two decades; the two men

continued operation of the foundry,

from which a variety of small iron goods

soon poured forth.20 Then in

1846, Leffel and Andrew Richards,

another energetic Springfield manu-

facturer, joined to build a cotton mill

and machine shop,21 located near

Buck Creek. This latter venture proved

unsuccessful, however, and the

facilities eventually were acquired by

the P. P. Mast Company.

As he was organizing his manufacturing

concerns, Leffel was becoming

one of the acknowledged industrial

leaders of Springfield. It was he who

first proposed to skeptical Springfield

manufacturers in the early 1840's that

a race for the effective utilization of

water power could be brought from

the outlying Buck Creek to a main

thoroughfare in the community.22

Leffel envisioned the establishment of a

complex of mills along the race

that would bring trade to the very

doorsteps of merchants and manufacturers.

204 OHIO HISTORY

He pressed his "favorite

scheme" on Samuel and James Barnett, two well-

established gristmill operators, and

they finally cut a race running a one

and one-half mile course from country to

town. Near its terminus, they

erected a "Water Power and Flouring

Mill." And Leffel himself raised

his cotton mill and machine shop by the

race. Several other mills were

soon located along the conduit, which at

its lowest water stage provided

enough power to operate twenty run of

stone.

Though busily engaged in foundry work,

Leffel was more concerned with

water wheel development. He used his

foundry for a series of experiments

in hydraulics and found time to construct

wheels for a number of mills

in the area. Where "economical use

of water was desired," he used a kind

of overshot wheel, which, according to

an adulatory biographer, "was so satis-

factory that he was almost induced to

believe it the most perfect form of wheel

that could be adopted."23 But

he always found some objection to his over-

shot wheel and resolved "to improve

the Turbine so that it would possess

all the excellent qualities of the

Overshot, without its defects." In fact,

This, then, became the great problem of

his life -- to construct a

Turbine Wheel to at least equal, or if

possible to excel, the Overshot,

in all circumstances and conditions.

Never, perhaps, did a man pursue

a fixed purpose with more devotion,

patience and industry. Day after

day, and year after year, the study of

Hydraulics, and experiments

connected therewith, occupied his

leisure hours . . . .

To convey some idea of the immense labor

he performed in this

department, we would say that he

constructed and experimented with

over one hundred different forms of

water wheels. Among these were

the Outward Discharge or Fourneyron

Wheel, the Jonval or Vertical

Discharge, the Center Vent, & c.

Each Different class underwent in

his hands numerous modifications . . .

.24

Despite his massive labors, Leffel

patented but two wheels. His first

patent, received in 1845, was for a

"new and useful improvement on a

bevel centrifugal water-wheel." The

patent was a characteristic inventor's

document, speaking as it did of the

marvelous utility of the wheel. Leffel's

"useful improvement" was the

multiplicity of wheel apertures, which

numbered "five times" as many

as found in ordinary wheels. Thus the

water of one inch or two hundred inches

could "be applied on the periphery

of this wheel to greater advantage than

upon any other known." Accordingly,

asserted Leffel, it would run in low and

sluggish streams "with less fall

than any other wheel." Moreover, in

times of "freshets" or high water,

"when other wheels refuse to

act," it would do a "good business," since

the high water was permitted to gather

toward the center of the wheel

without diminishing wheel speed.25 Though

not a true water turbine, the

wheel incorporated at least one

characteristic feature of turbines: water

ran through it rather than simply upon

the circumference. But neither

reaction nor impulse principles were

utilized in the wheel.

So certain was Leffel of the

effectiveness and salability of this wheel he

gave over a portion of the foundry

capacity to its production. Expecting

to generate a local demand first and

then area demand, he employed the

JAMES LEFFEL 205

wheel in his cotton mill and machine

shop. But his act of faith moved only

a few Springfield manufacturers to a

similar decision, and his roseate hopes

for sales were not realized. Though

continuing to experiment with water

power mechanisms, he turned all of the

foundry facilities back to the

production of older, more marketable and

more prosaic goods for the farm

and home.26

If Leffel had failed in his initial

effort to invent and market a water

wheel, he remained, nonetheless, an

important manufacturer in the com-

munity. By 1850 he had achieved a kind

of security and maturity in his

industrial ventures. He had given up his

interest in the cotton mill, but he,

Richards, and Blackeney had developed a

machine shop and foundry of

considerable size for the time and place

at the site of his first foundry

west of Springfield. According to the

returns of the census of manufacturing

for 1850, capital invested in the

foundry and machine shop was $18,000,

the second largest investment in Clark

County; only the $27,000 of the

Samuel Barnett flour mill exceeded it.27 The works employed fourteen

"hands," the second largest

work force in the county, and produced

annually stoves and machine castings

valued at $15,000, the stoves account-

ing for $10,000 of the total. The

national average for capital invested in

iron foundries was $11,000, and the

national average for capital invested

per worker was $773 -- far below the

$1,300 behind each Leffel employee.28

With Leffel providing its inventive

drive, the firm achieved substantial

status in the early 1850's. One

prominent item fashioned in the foundry

in the period was an improved lever jack

that Leffel patented in 1850.

It was, unfortunately, linked with a

tragedy for its inventor; during a trip

to California, where he was selling the

jack, his son, Wright Leffel, was

drowned.29 Leffel's cooking

stoves, the "Buckeye" and the "Double Oven"

or "Red Cook Stove" earned a

good reputation for him among Miami Valley

housewives. Patented in 1849, the

"Double Oven," was supposedly the first

stove in Ohio that threw the flame down

over the oven at the base of

the stove; the oven heretofore was

usually placed in the center of the stove.30

Some forty years later, Ohio's pioneer

historian, Henry Howe, recorded

that the latter was the first cook stove

invented in Ohio and quoted

an old citizen who believed that

"no better has succeeded it."31 For some

reason or other, despite the success of

the firm, Richards left it in 1852.

Nathaniel Cook, a machinist, then joined

Leffel and Blackeney in the

partnership.

With the foundry turning out salable

products of good repute, Leffel

increasingly turned to his water power

endeavors in the mid-1850's. He

improved his facilities for hydraulic

experiments, determined as ever to

be a turbine inventor. As a contemporary

observer put it, he was a "person

who would undertake almost anything he

set his mind to do."32 And "to

do" an improved water turbine

remained his compelling purpose in life.

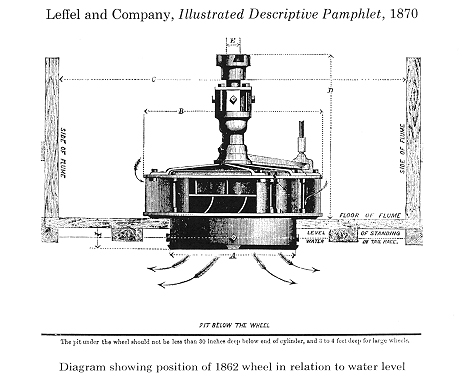

Finally in 1862 his years of labor bore

fruit. Early in that year he was

granted a patent for a reaction type

turbine wheel.33 The turbine was literally

Leffel's "pride and joy." The

inventor carried his model constantly, placing

|

it under a handkerchief in the crown of his plug hat and withdrawing it for display at the slightest encouragement. He was absorbed in it and could talk of nothing else.34 Leffel demonstrated the effectiveness of his creation in several dramatic ways. In Springfield he erected a mill for the processing of linseed oil, not primarily for oil processing but rather as a showcase for the wheel in produc- tive use.35 Confident of the superiority of his double turbine, he agreed to test it against the center-vent, horizontal wheel designed by Dr. Tobias Kindleberger of Springfield, a pioneer homeopath who had operated a "general manufactory" in the community for two decades.36 The contest was conducted on May 2, 1862 at the Methodist Publishing House, where both wheels were installed side by side. Men from all over the state, reported the Springfield News, came to view the exciting battle of the wheels. "With a sort of ingenious brake attached to the shaft," marvelled the News, "the Leffel wheel made 125 revolutions per minute, and exerted a force of 21 pounds."37 The Kindleberger wheel made only 100 revolutions per minute and exerted a force of 16 pounds; moreover, the Leffel wheel did not use as much water. The News also rejoicingly noted that a Leffel wheel, only ten inches in diameter, had been in use in its own office for several months. There it had been running a large Adams book press, a Northrup cylinder press, and two job presses -- often at the same time. Such practical usage stemmed from Leffel's distrust of test runs, which he believed could not duplicate actual conditions of manufacturing. |

|

Why his invention worked so well, Leffel himself, it was said, could not explain.38 His hydraulic notebook, in which he recorded the results of the encounter with the Kindleberger wheel, indicates, however, more than a fortuitous gathering together of parts by Leffel. Though probably he had developed the wheel's efficiency through laborious trial and error methods, the notebook demonstrates that Leffel was well acquainted with the theory and practice of hydraulic physics.39 Certainly he was confident that he had developed an effective mechanism. He asserted in his patent application that it was capable "of yielding from ninety-two to ninety-five per cent. of the power of the water and a greater per cent. than any other wheel heretofore constructed."40 The wheel, evidently designed to utilize small water-loads, was a reaction turbine with mixed flow, its sets of upper and lower vanes developing inward and downward flow. In the words of one authority, This improved Leffel wheel was a double bucket design, namely, with a ring of upper buckets and a ring of lower buckets immediately below them and arranged so that the water would pass through both of these sets of buckets and on out into the draft tube in the most efficient manner, thereby creating the highest results in power and speed for the amount of water and the fall of water that were being utilized.41 This use of double buckets, a technique apparently never employed by any other manufacturers before or since, was elaborated in later years into a more modern type of wheel.42 |

|

208 OHIO HISTORY

Convinced that he could sell the wheel to mill and factory operators, Leffel dispatched his son, Frederick Leffel, on a mission through the Midwest and East to broadcast the good news and hopefully waited to receive orders. Evidently the son also took a model West to display to miners and millers. The fortunes of the turbine were regularly charted in the pages of the Springfield News. As the paper chronicled the event, the first notable sale of the turbine, marketed as the American Double Turbine, was recorded at Rochester, New York. There, a flour mill operator, needing to grind four hundred barrels of flour in twenty-four hours, asked Blackeney to run a trial with the Leffel wheel. In the trial run, the turbine produced not four hundred -- but seven hundred barrels in the specified time.43 According to the News, the double turbine "knock[ed] the spots off" its competitors in Rochester. Rochester millers who observed the trial run must have agreed with the newspaper assessment: within a few days after the run, they placed at least six orders with Leffel.44 As these orders and more were received in late 1862, Leffel and his partners raised the number of employees working on wheel production from ten to twenty and put them to work "night and day." |

JAMES LEFFEL 209

Leffel himself determined to use his

wheel for productive purposes.

In December of 1862 he purchased five or

six acres of land near Lagonda

Creek in Springfield. Here he intended

to build a large flouring mill that

would be capable of turning out one

hundred barrels of flour a day.

Mechanical power for the milling was to

be supplied by Leffel's double

turbine.45 By March of 1863

the plans for a four story building had been

completed, and the construction work was

ready to begin.46 The subsequent

operation of the mill represented

continuing and dramatic evidence of

Leffel's faith in the double turbine.

Meanwhile Leffel was involved in

re-ordering his business interests.

Sometime in 1863 he and Blackeney formed

a new firm, evidently a joint

stock company, taking on as associates

Perry Betchel and Leander Mudge,

two rather non-descript businessmen.

Physical changes were also taking

place. By March of 1863 the demand for

the "best [wheel] in the known

world" had increased so much that Leffel expected to increase

the work

force from twenty to over a hundred and

fifty in the "coming season."47

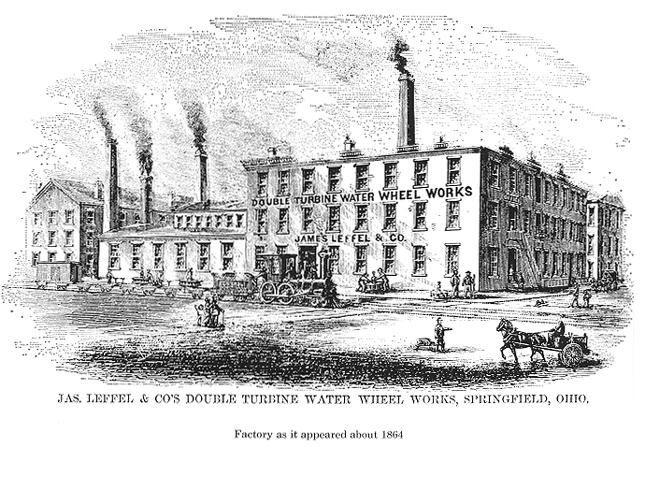

In December of 1863 he arranged the

purchase for $6,000 of the Springfield

property on the corer of Limestone and

Washington streets owned by

the Pitts Machine Works, the

manufacturers of the thresher invented by

John and Hiram Pitts in 1834.48 Soon a

foundry designed solely for the

production of the "celebrated"

wheel was being erected on the site.49

The building, 107 feet by 50 feet in

exterior dimensions, was completed

in March of 1864. Before production in

the facility could begin, Leffel

had to fabricate the machinery for

manufacturing the wheel.50 Once fitted

with machinery, the foundry employed

more than fifty men. Despite the

mounting success of their business, the

partners evidently did not get on

well together. Betchel left the firm in

early 1864 and was replaced by Henry

Barnett. But, as one observer later put

it, the "combination did not seem

to be progressive and desirable,"

and in 1864 still another reorganization

was effected.51 This time Leffel joined

with John Foos and James S. Goode

in forming a stock company, James Leffel

and Company. Blackeney, Lef-

fel's long-time associate, did not

continue in the business. Foos was a well-

known linseed mill operator, and Goode

was a lawyer and jurist who

had been mayor of Springfield in the

1850's.52 A year later, in 1865, yet

another organizational change occurred.

Now Goode and Foos took their

leave, and Leffel's son-in-law, John W.

Bookwalter, and William Foos

entered the firm with Leffel; the firm's

name then became The James

Leffel and Company.53

All the while demand for the double

turbine increased. Orders for it

totalled forty-seven in 1862, rose

modestly to sixty-two in 1863, and jumped

to 153 in 1864.54 Initially,

orders came largely from the mid-western and

middle eastern states -- from towns and

cities in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan

Pennsylvania and New York -- from

Dayton, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh and

Rochester. Customers were flour mill

operators, woolen goods manufacturers,

paper producers and farm equipment makers,

to name a few. By 1864

the wheel was reaching national and

international markets; orders were

|

being received from points in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Minnesota and Canada. The hardworking Mormons of the Utah Territory looked with favor on the American Double Turbine; one Joseph Croft of Salt Lake City, representing a number of millers there, ordered fourteen wheels of assorted sizes costing over $3,000. In 1865 orders totalling over $37,000 were received from California and Oregon, the western regions to which Leffel's son, Frederick, had carried a model on a sales trip. Prices varied, depending, of course, upon wheel size. Typical sizes ranged from thirty inches to forty inches in width, their prices in 1862 running from $350 to $500, with complementary gear resulting in different prices for identical models. Smaller wheels were ten and thirteen inches and usually were priced below $200. The largest one manufactured in the early years was a fifty-six inch wheel, ordered by Andrew Erkenbrecher of Cincinnati at a cost of $700. The success of the American Double Turbine probably was the result of various factors. Certainly the reputed effectiveness of the wheel com- mended it to potential buyers. Its efficiency with both full- and part-water loads widened its market. The variety of users suggests that it could be adapted to varying water conditions. Though prices of comparable wheels are not known, Leffel's evidently was competitively priced. The range of prices, moreover, fell within the reach of small producers, thus giving the wheel access to a large market. Its workmanship was excellent, an attribute perhaps stemming from Leffel's experience with stove castings. Its low |

JAMES LEFFEL 211

cost of maintenance and durability

further enhanced its position in the

market.55 Little

is known about Leffel's marketing methods, but clearly he

did seek to generate demand beyond the

Springfield area, dispatching as

he did his son on sales trips throughout

the nation and sending the wheel

to the East for trial runs.

Whatever the factors behind the

popularity of his wheel, Leffel was not

destined to enjoy long the fruits of his

success. In 1866 he died, but his

double turbine wheel and his name were

firmly rooted in the industrial scene

of Springfield. By 1870 the company

bearing his name could boast a capital

investment of $120,000, and its annual value

of production had reached

$371,400; turbine production alone

accounted for $250,000.56 The firm

employed sixty-five men, who were

primarily working on the turbines. With

his water turbine the small foundryman

had laid the foundations of a great

company; The James Leffel & Company

still exists in Springfield and con-

tinues to manufacture hydraulic turbines

as well as scotch boilers and

stokers. It stands today as a monument

to a man of genius and tenacity;

well might his motto have been Tenax

propositi.

THE AUTHOR; Carl M. Becker is In-

structor of History, Wright State

Univer-

sity.