Ohio History Journal

edited by

LOUIS FILLER

Prevailing Manners and

Customs

on the Frontier: The

Memoirs

of Irene Hardy

Irene Hardy, schoolmistress, poet, and

early Stanford University

professor, was born July 22, 1841, in

Eaton, Ohio, the eldest daughter of

Kentucky and Virginia parents. Her

father, Walter Buell Hardy, was a

schoolteacher of culture whose four

daughters-he also had a son,

Lewis-all taught school successfully.

Irene was so named from a

character in Edward Bulwer-Lytton's

novel Rienzi, with conscientious

regard for the original Greek

pronunciation. Her mother was an

enthusiast for education, who declared

that if she had twenty daughters

she would send them all to college if

she could.

Irene early became a school teacher, and

saved money to enable her

to enter Antioch College. As she had

occasion to write in a letter to the

later president of Antioch College,

Arthur E. Morgan,

I entered Antioch in September, 1861, as

partial freshman. My preparatory

school had given me no Latin, no Greek,

and no ancient history. I had, therefore,

to do three years' work in these

subjects, which I did in two years. At the end of

that time, owing to conditions brought

about by the war, the College classes

were suspended for one year and the

faculty gave all their time to the preparatory

school.

I went home to teach. To shorten my

story,-I was in and out of college a

number of times to teach, until 1867,

when I was nearly ready to take my degree.

Although I was matron of North Hall and

teacher in the preparatory school from

1874 to 1876, I did not care to take my

degree, notwithstanding I had done work

enough to entitle me to it: nor was I

ever afterward a student there. In 1871 I

came to California,1 and on a

return visit in 1883-4, when Dr. David Long was

President, he urged me to take my degree

at the next commencement. I could not

return to do so, but the degree was

granted in 1885-eighteen years after it was

mainly earned.2

Dr. Filler is Professor of American

Civilization at Antioch College.

1. Irene Hardy returned to Antioch

College, as indicated, for the years from 1874 to

1876, then left permanently for

California.

2. Irene Hardy to Arthur E. Morgan, June

19, 1921, Hardy File, Antiochiana, Kettering

Library, Antioch College.

42 OHIO HISTORY

At Antioch, Miss Hardy was of an era of

notable women students:

Olympia Brown, known as the first

regularly-appointed female minister

in America; Susanna Way Dodds, a pioneer

physician and reformer,

who refused to accept her Antioch degree

because she was not

permitted to wear her Bloomer costume

for the occasion; and Ada

Shepard, who accompanied the Nathaniel

Hawthornes to Europe as

governess for their children. As Miss

Hardy says, she then went west,

primarily for reasons of health, but

stayed to develop a California

career, interrupted then renewed, as a

schoolmistress. As such, she was

influential in developing standards for

composition and the teaching of

literature for the entire state,

publishing a textbook which was used

widely in the public schools. She was

influenced by the poet Edward

Sill, of the University of California,

and wrote much verse. Some of it

appeared in magazines and in collections

such as an 1892 volume,

privately printed in Oakland, and one

published by a San Francisco firm

in 1902. These and her teaching

activities gave her considerable local

and regional prestige.

In 1894, she joined the Stanford

University faculty and gave courses

in American literature, composition, and

short story writing. The honor

she accrued is exemplified in an article

by a colleague of hers, Melville

B. Anderson.3 Herbert Hoover

was among many of her students who

remembered her with affection and

respect. In 1919 Hoover, then at the

height of his pre-Presidential fame,

opened the assembly at Stanford

University with a talk on the Treaty of

Versailles, which recently had

been consummated. Miss Hardy received

from him a copy of his

address.

In 1901, she retired from active

teaching to a cottage "built for her by

appreciative students."4 In

1908 she went blind. That same year she

started the writing of her memoirs,

"The Making of a Schoolmistress."

It was completed in 1913, and comprised

530 pages of manuscript. It

took her up to the beginning of her

Stanford University career, and

included such matters as her meeting

with John Muir and Dr. Edward

Everett Hale; a vignette of Horace Mann,

whom she saw during a visit to

Antioch College; a reception for General

Ulysses S. Grant; and

friendship with the widow of John Ross

Browne, the humorist, traveler,

and government official.

Her seventy-fifth birthday in 1916

brought many letters and

felicitations from students and friends.

She died of pneumonia at her

home in Palo Alto on June 3, 1922. She

was survived by her sister

Adelaide, also a poet and teacher, and

her brother Lewis. He made

3. "Malcolm Playfair

Anderson," The Condor, XXI (May 1919), 115-9.

4. Palo Alto Times, June 5, 1922.

Manners and Customs 43

efforts to get his sister's memoirs

published, but after failing to gain

support, gave the manuscript, along

with other materials of Irene and

Adelaide, to the Antiochiana section of

the Antioch College Library.

There the poems, letters, clippings,

and other matter were preserved,

thanks in large part to the good

offices of the late Miss Bessie L. Totten.

Miss Hardy's memoirs deserve ultimately

to be republished in full.

Hers was a typical frontier life-style,

and her memories of her childhood

illuminate the quality of life in the

small Ohio settlements of the

mid-nineteenth century. In the

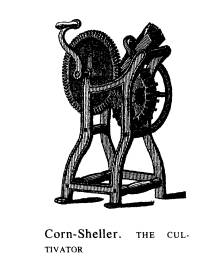

following chapter, for example, she deals

with such things as shelling corn,

holding apple-cuttings, sharing food

and work with neighbors, and making

quilts. Together, these

descriptions give her readers a good

sense of the "prevailing manners

and customs" of rural Ohio in the

1840s.

PREVAILING MANNERS AND CUSTOMS

Household Manners

The household manners and customs in

the [eighteen] forties and

fifties were necessarily simple. As the

furnishings of the settler's cabin

and the later log house were determined

beforehand by necessity, there

was little reason for formality and

elaboration. When the mistress of the

house had finished preparing the meal

she called the family, took off her

apron, sat at the head of the table,

and poured the tea, coffee, or milk.

The master of the house took his place

opposite. Everything that was to

be eaten at that meal was on the table.

The plate of bread stood at the

master's right hand, the pie or pies

stood on the other corners of the

table. Meat, vegetables, preserves,

butter, and apple butter occupied

the middle of the table. One plate,

upside down, one knife and fork

(two-tined) had been put down for each

person. Tea and coffee were

poured from the cup into the saucer to

drink, the cup was set on a little

cup-plate, in the better ordered

families, to prevent rings of stain on the

homespun linen. Nor was there any

prejudice against using Solarino's

method of cooling his broth for cooling

the tea if it were still too hot after

pouring into the saucer. Pie was

usually a part of every meal and was of

course eaten from the same plate as the

rest of the dinner. Napkins were

not in use; this omission, however, was

not so barbarous as it may

sound, as table rules about dropping

things on the floor or on the table

cloth were very severe, both for grown

people and for children. There

was no exception to these customs in

the neighborhood. It was not until

the middle fifties that the cup-plate

wholly disappeared and everybody

drank tea and coffee from cups with

handles. Somewhat later than this

the small sauce-plate began to appear.

The men were called from the

44 OHIO HISTORY

field at half-past eleven by a long tin

dinner-horn and the dinner was

served promptly at twelve o'clock.

All the cooking and other work requiring

fire was done at the

fireplace, except such larger operations

as had to be done out-of-doors

in the iron or copper kettles, until my

fifth or sixth year, when my father

and mother bought a stove, which was put

into the lean-to at the nearer

end. There were but two other stoves in

the neighborhood then, I

believe-one at my grandmother's, and one

at Mr. Bremerman's. Our

meals had heretofore all been cooked by

the open fire, in a three-legged

bake-oven (elsewhere called a

Dutch-oven), in three-legged skillets, and

in iron pots which hung on hooks from a

bar put across inside the

chimney, which took the place of the

crane common in New England.

Bread was baked in the three-legged oven

set on coals before the fire,

and covered with coals which were kept

in place by the flange around the

iron lid. Yeast-bread, salt-ricing,

corn-pone, biscuits, flat-cake,

griddle-cakes, corn-dodger, corn-bread,

pumpkin-bread, and

snow-bread in its season,

crackling-bread, cakes and pies, rusks and

gingerbread-all came in turn out of the

three-legged oven. As I never

knew of snow-bread in use anywhere

excepting in our family and my

grandmother's and as I never find anyone

now who ever heard of it, it

seems worthwhile to tell what it was,

and how it was made. It was a

bread of corn meal made with snow after

the following directions: To a

quart of fresh corn meal salted to

taste, add two quarts of fine drifting

snow; take the meal out-of-doors in a

cold pan, stir in the dry mealy snow

thoroughly, then pour the mixture at

once into a large buttered dripping

pan, sizzling hot, in the oven, spread

level with a spoon and bake in a

quick oven about as long as ordinary

corn bread. If successful, you will

have a crisp, sweet, delicate bread,

delicious eaten with new milk for

supper. This bread can be made only in

very cold weather, when the

snow is dry, and drifting about. We

children used to beg for it whenever

we saw that the snow was right.

There was no stint of food anywhere in

the settlement. Everybody had

a generous table; the very best

home-cured meats, raised on their own

farms by the farmers themselves on the

table three times a day, with

changes of fresh killed meats, fowls,

eggs, vegetables and fruits,

maple-sugar and syrup made in February

and March from their own

sugar-trees, dried apples and peaches in

winter with all manner of

sugar-preserved fruits, berries, pears,

with loads of apples from the

orchards-all these furnished the tables

with an abundance I have since

seen nowhere else. The simple manner of

serving in families in which

every part of the work was done by its

members made all easy enough in

comparison with the elaborate

artificiality of more modern eating.

With sewing, weaving, spinning, dyeing

of wool and flax-when all is

Manners and Customs 45

said, women had more time to live than

they find now. Clothing was

simply made, but with the greatest

pride in the handwork of the

stitching, hemming, and gathering.

Men's best shirts were marvels of

beautiful sewing, counted threads in

the gathers, and stitched fronts.

Women's gowns were sewed together at

the waist with thread-counted

stitches.

Economics and Occupations

The usual custom of early to bed and

early to rise prevailed in the

neighborhood. Breakfast was commonly

eaten by candle light in the

winter time, and at night the fire was

covered and the lights were out

often by eight o'clock. Unless somebody

was sewing or reading, the

fireplace furnished the only light for

the evening circle. A single candle

or the lard lamp was the only other

light in use even to the early fifties.

Tallow and wax candles were made in my

own home, often with my help

in putting the wicks into the molds

ready for the tallow or wax. As we

never bleached the beeswax, our wax

candles were usually dark in

color.

The dye stuffs used by the various

families were lump indigo,

cut-bear,5 copperas,

log-wood, cochineal, madder, and anatto.6 These

were of course bought of the druggist.

Saffron from the garden, black

and white walnut barks, yellow poplar

bark,7 willow bark, mosses and

lichens from the woods were some of the

natural vegetable dyes

available, though generally not in

favor. Skeins of vari-colored yarns

drying on our yard fence, and often at

our neighbors, were familiar sights

to me as a child.

Although matches had been invented,

they were not in use in our

neighborhood in the forties and early

fifties. I do not remember seeing

matches, though there must have been

some in our house before the end

of this decade, as I do remember

having, and seeing other children have,

the little wooden cylinder boxes in

which matches first came. These

little boxes, as indeed any small box,

were a rare and precious plaything

to us children. The candle or lamp was

lighted with a burning stick from

the fire. People who smoked searched

round on the hearth for a coal of

suitable size to be taken up in the

bowl. If in the warm days of spring the

fire was allowed to go out, someone

went with a shovel to the neighbors

to bring back live coals to relight the

fire. In summer-time fire was kept

on the hearth by covering with ashes.

5. The word cud-bear is a corruption of

cuthbert from the name of Dr. Cuthbert Gordon,

its discoverer. Botanically it is a

lichen, Lecanora tartarea. It makes a rich purple color.

6. Anatto is a yellow dye made from

berries of a semi-tropical tree, used for coloring

cloth only, not for butter.

7. Liriodendron tulipifera.

46 OHIO HISTORY

As there were no postage stamps and no

envelopes in those days,

letters were folded in squares without

a covering and sealed with wafers.

Letters were prepaid or not, as the

writer chose. And it sometimes

happened that an inconveniently large

postage fee was demanded before

one could have his letter.

Carpets, even rag-carpets, did not come

into general use until about

1850. In the hewn log-houses which

succeeded the settler's cabins, there

was generally a "big room"

which might have a rag carpet, or on the

more enterprising farms, a

"girthing" carpet, which was a home-woven

fabric, made of brightly colored

home-dyed woolen yarns, used as very

closely laid warp which covered the

woof or filling of coarse yarn. The

reds, greens, and yellows were usually

graded in arrangement from dark

to light, and made very bright stripes

lengthwise of the web. It was called

girthing because it was woven like saddle-girthing.

The first I ever saw of

this kind was at the house of a

neighbor named Gardner, about 1847. It

was a piece of news to tell when this

or that neighbor had finished her

piece of girthing-carpet and was going

to lay it on her big room floor. It

was like walking on rainbows to enter

such a room. A little later one or

two families bought what was called a

Turkey carpet, a finely woven

two- or three-ply fabric, invariably of

brilliant red and green figures on a

ground of the same color.

The larger operations of household

economy such as soap-making,

washing, apple-butter making, and

dyeing, before the advent of stoves,

were done in large iron or copper

kettles, hung over the fire

out-of-doors. A stout pole was laid

across two firmly fixed forked posts

about eight feet apart. On this two or

three kettles hung by the iron bails

so that the fire could be build

directly under. Extra water for scrubbing

the floor, or scouring the wooden

covers of the milk crocks, or preparing

the lye for lye-homing was heated

out-of-doors. A necessary addition to

this out-door fireplace was the

ash-hopper for the making of lye out of

ashes. Sometimes the hopper was made of

small logs laid on a slant

platform, but generally of four-foot

clapboards set up in the shape of an

inverted truncated pyramid on a slant

floor. The ashes were put into this

on a thick layer of straw which served

as a filter to the lye running off into

a wooden trough. If lye of greater

strength was wanted, the

already-leached ashes were taken out

and thrown aside, new ashes put

in, and the lye from the trough poured

in once more. The strength of the

lye was tested by seeing whether it

would bear up an egg or not. In some

families, as in our own, I remember, a

fine starch was made by the

women by stirring and soaking wheat

bran in a tub of water, until the

whole fermented, the starch sank to the

bottom, the bran was poured off

with the superfluous water, and the

cake of starch at the bottom taken

out and dried on plates. This was used

for starching the finer linens.

Manners and Customs 47

Common flour starch served for ordinary

use.

Up to the end of my tenth year (July

1851) my life had been that of a

child in a semi-pioneer settlement; for

the township in which I lived was

just beginning to emerge from the

farm-clearing, log-cabin days, and the

simple manner of living of those times

still prevailed. Our clothes were

hand-woven and home-made; we raised our

own wool and flax, and

prepared these for the loom; the wool,

by washing, picking, and carding,

and afterwards spinning and dyeing; the

flax, by pulling and rotting in

the fields, breaking, scutching,

hackling, and then by spinning and

weaving into linen cloth for all

household purposes, and for summer

clothes. We made all our sugar from the

maple trees. Of all these things I

was a part, and took my part, to the

extent of learning the processes by

sight, and some by practice. I learned

to spin wool and flax, though of

course I did little of it at so early an

age. I "handed-in threads" in the

operation of "putting in a

piece" of cloth, I "filled the quills" for the

shuttles by turning the little

quill-wheel and the winding-blades. Not

until all the quills had been filled in

the mornings was I free to go with my

sister to the woods to play. Usually my

mother gave me three skeins

from the spun wool or linen hanging in

the "loft" to use for filling the

quills. I looked them over, took the

most tangled one first-I had learned

this myself because it was my experience

already that the nearer the

time came to go out to play, the harder

it was to wait to untangle yarn,

that the time seemed to come more

quickly when I could turn my wheel

fastest with the smooth last skein.

"Handing-in threads" was a

tedious process: I sat behind the heddles,

between them and the warp-beam, passing

to my mother on the front

side of these "gears," as they

were generally called, each thread, one by

one in its warped order, with nothing to

see or to hear, but

"one-thread-at-a-time-with-attention."

If by chance one thread was

omitted and the next put into its place

undiscovered for some time, then

all must be taken out and done over; and

it was warm and close and

stupid. My mother could easily have

lightened my task by stories, but if

she had tried to do so she could not

have given her attention to "a thread

at a time just so," and mistakes

would have crept in. Sometimes my

Grandmother Ryan came in and relieved me

by taking my place behind

the heddles.

It should be explained perhaps that the

"quills" were made of

branches of elder by cutting them into

about four-inch lengths and

pushing out the pith; these were used as

bobbins on which to run the

thread for the shuttle.

I have said elsewhere that almost

everything used by the farmers at

this time was made at home. This

included many of the farming utensils

and conveniences for carrying on the

varied kinds of farm and household

48 OHIO HISTORY

work. There was no money to spend, for

example, for buckets to be used

in [maple] sugar camps, so that vessels

for collecting the maple sap had

to be made by hand. These were usually

troughs dug out with chisel and

mallet from a split section of a log,

two or three feet long. At the end of

the sugar season the troughs were either

gathered up and stacked in the

camp shed or, what was more common, each

was turned up on end

against a tree.

Hardships of some kinds were so common

that they became the

source of certain habits, which were

afterwards followed by

preferences: for example, the habit of

going barefoot. No child would

willingly have worn shoes in the spring

and summer, nor put them on

until the winter snow fell. As all the

farmers made their own shoes and

those of all their family, there was no

waste of such necessary work.

Usually, the calf-skin too was of their

own manufacture. The

shoe-bench and kit of tools was as

necessary a part of the house

furnishing as the wheel and loom. Grown

men and women, however,

seldom went barefoot; that was regarded

as shiftlessness. My first pair

of shoes, made by my father, served me

until I was four, so far as I now

remember. The shoes were always made on

straight lasts and the

children were required to change them

from left to right as did the grown

people. Very often the lasts were

whittled out at home, thread and pegs

were prepared there also. The sewing was

done by means of an awl and a

thread with a pig bristle twisted into

the waxed end.

The day I was taken to the new

schoolhouse in Dooley's district-five

or six, I must have been-was in October.

We started early, while the

frost was still on the ground. I was

barefoot, for the day promised to be

sunny and so far warm, and besides, I

had no shoes, and it was too early

to begin wearing them if I had had any.

The road was dry and dusty, but

frosty most of the way. I drove up some

cows, still lying in the road

waiting to be milked, and warmed my feet

in the spots which they left.

This was a trick I had more than once

enjoyed, when there was no

particular need as on this long cold

walk.

As almost everything that was eaten on

farms was produced there,

few excuses for borrowing ever came;

sometimes a cup of green

coffee-beans, or a little saleratus, or

any such small matter. Every family

seemed sufficient to its own immediate

needs. But there was always a

good deal of friendly exchange of

commodities. "Don't you folks want

some currants? We have more than enough,

come over and help

yourselves." Or, "Our early

apples are ripe, and yours are not in yet.

Send over and get some." Or maybe,

"Mother sent over these turnips,

ours are earlier this year."

"Why, much obliged surely, and I'll just put

some of these spare-ribs and a mess of

sausage into your basket." The

compliments of the season went back and

forth between neighbors all

Manners and Customs 49

the year round; if there were kinds of

fruits or vegetables that one's

neighbor had not in his garden and

orchard, then it was a privilege to

send them to him. "Come over and

help us." was not often said,

because those who could help

anticipated the cry. The hard things in

pioneer life were offset by such real

compensations. And yet how

simple, uneventful, and slow it

looked,-and looks now to those who

see from without! I hardly think our

neighborhood was any better or any

worse than the neighborhoods that

pieced on all around. True we had

few shiftless, few very poor, and few

unthrifty among us. All were at

least trying to live decent self-respecting

lives. I do not remember more

than one family-and they disappeared

while I was still very

young-whose house was dirty and whose

women and children wore

dirty clothes. They were subjects of

comment so often that one who

listened even to what she did not

understand could not forget,-and

could not on after occasions fail to

observe.

Shelling Corn for the Mill

Shelling corn for the mill was an

evening occupation which came

whenever fresh corn meal was needed for

bread. The best ears of mill

corn were chosen, brought in after

supper in the bushel basket, and set

by the fire. At home my father, helped

by the two children who were old

enough, shelled, while my mother sat

sewing or knitting by the candle or

the lard oil lamp, or perhaps by

firelight. When enough cobs had been

stripped of grain my sister and I built

cob-houses, which we begged to

have set on the coals between the

andirons-"to see the house burn."

But every grain must have been taken

off; it was wicked to burn corn. If

corn-shelling took place at my

grandfather's when I stayed all night

there, the scene was much the same,

except that more took a hand at it,

there were no cob-houses, and the next

morning someone, usually the

youngest, who was I, had to get down on

the hearth and pick all the

grains out of the cracks of the

flag-stone hearth before sweeping was

done. For it was wicked to burn

anything that any creature would eat,

and although there was abundance of

grain and other food for all the

fowls, at their command as it were,

this rule was so rigidly observed that

none of my grandfather's children would

have broken it, for two

reasons,-fear of punishment by my

grandfather, and "because it was

wicked." What Grandfather said was

wicked was doubly so, because

nobody thought him a religious man.

I have heard my father say that he had

gone into the corn-field in

October to get ears of ripened corn to

grate on the kitchen grater to make

meal for bread for breakfast.

"But," added he, "that was not

uncommon in the wilderness times in

Kentucky in my father's early

family life. He lived thirty miles from

a mill, and my oldest brother had to

|

50 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

go on horseback that distance with a bag of shelled corn behind him to bring back meal for bread." In our part of the country there had been Bruce's Mill since 1812, so that going to mill was a simple matter. In my childhood grating corn for meal was never merely on account of need; but the old necessity of doing it had left a taste in the mouths of the farmer folks for a supper of mush-and-milk made from the freshly grated and sifted meal of the first frost-ripened field corn; and for the new corn-bread next morning of the same sweet handmade meal. When a bag of corn was taken to mill one waited until it had been ground. It was then returned to the bag unbolted, that is, with the bran still mixed with it. The sifting was done by hand at home as the meal was used. When a farmer took a sack of wheat to mill he took home with him the bolted flour, the middlings or shorts, and the bran. In each case his grist was less the miller's toll, which varied, I believe, with the quoted prices of grain. Apple Cuttings An apple-bee, or apple-cutting as it was called in the Middle West, was a common entertainment in the fall among the farmers. After the summer's work was laid by, in the lull of the year, the apple-orchards were scenes of jollity and abundance. The early fall apples and what were left over from the late summer trees were gathered in heaps in the orchards among their own trees, some for the cider-mill and apple-butter making, and some for drying. For both of these processes large quantities of apples, peeled, cored, and quartered, were necessary, as every family made at least a half barrel of apple-butter, or never less than |

Manners and Customs 51

one big copper kettle full. Dried

apples were greatly depended upon

also, as fruit-canning was then not

known. Preserving meant jellies,

sugar preserves, thick and rich, and

made so strong as to require no

sealing.

Usually invitations were sent about by

word of mouth a few days

before the apple-cutting was to come

off. Tubs, baskets, large kettles, all

sorts of receptacles came into use to hold

the apples brought into the

house for the workers. Usually the

"married folks" came and worked all

day or afternoon, peeling by hand and

with peelers, coring and

quartering, and spreading out on

improvised scaffolds in the sun to dry.

At noon or later a dinner, such as

[Washington] Irving describes in "The

Legend of Sleepy Hollow," was

served. Some of the visiting women

helped the hostess to make ready what

was necessarily left to be

done-coffee, hot biscuit, and

vegetables. Before the neighbors left

there was a clean-up after the work and

more apples were brought in for

the young folks who were to come to

work after dusk. More baking of

pies, cakes, and biscuit, and supper

for the family alone, while the old

folks went home to send the young ones

for their share of work and fun.

Then work, with jokes, tricks, counting

apple-seeds to be

named--"One I love, Two I love,

Three I love I say, Four he loves, Five

she loves," etc., throwing a long

peeling around the head to see what

letter it would make. (How did it

always happen to make the right one?)

Jokes about Ben's slow peeling, or

Nancy's slow quartering, or Mary

Ann's poor coring, "Leaves half

the core-eyes in," "And you leave a

ring 'o peelin' on boths ends of every

apple, and that's why I can't keep

up corin' for peelin' after

you-huh!"

Then came supper, apple and pumpkin

pies, cider, doughnuts, cakes,

cold chicken and turkey; after which

games, "Forfeits," "Building a

Bridge,"

"Snatchability," even "Blind Man's Bluff" and "Pussy

Wants a Corner," then going home

in the moonlight. All these customs I

knew of before I was ten years old, by

having been present at an apple

peeling in my own home, and one at my

grandmother's.

Quiltings and wood-choppings were other

forms of neighborhood

helpings in common. There were no hired

people in those days in that

community, so that when a man or woman

had too much of any one thing

to be done by one person, everybody

lent a hand and made good times

and quick work out of it all; always,

of course, with much good eating

and plenty of simple and wholesome fun.

Husking, sheep-shearing,

wool-picking, carpet-rag cuttings,

geese-plucking, corn-planting,

house-raising, log-rolling, sewings,

furnished times and occasions for

festivities. With most of these forms

of amusement I had become

familiar before my father moved his

family to Eaton, where there was

seldom need of neighborhood civilities

of this kind.

52 OHIO HISTORY

The custom of serving a drink of whiskey

to the men in the

harvest-field and at house-raisings was

going out of favor in the middle

forties, as was that of offering toddy

to casual callers. I have a dim

recollection of hearing an argument by

someone with my father because

he had said he did not intend to offer

drink to the men at his hay-harvest.

"Then the men will not come."

"Well, they can stay away then,"

answered my father. This seemed to be

about the time of the last struggle

for existence of this custom, as I never

saw or heard of any further use of

it. I never heard of any custom of this

kind in my Grandfather Hardy's

family who, though Kentuckians, were

decided total abstainers.

Patchwork Quilts and Garden Seeds

Whenever a neighbor came to spend the

day on a visit to my mother, a

part of the entertainment consisted, as

a matter of course, in showing her

patch-work quilts, finished or in

process of making, a piece of cloth in the

loom, or lately woven, and any new

garment made or in the making. In

the same way every quilt pieced and

quilted in the neighborhood was

known and spoken of in other houses. For

the most part the quilts were

pieced of scraps of calico or gingham

left from the few dresses of those

materials owned by the maker and added

to by the friendly exchange

with neighbors, each woman generally

brought back from a visit a little

roll of quilt pieces, and every woman

could tell, in showing her quilt, of

whose dress or apron or bonnet each

square was a piece. Before I was

eight years old I used, while still in

bed in the mornings, to say, "This is a

piece of mother's dress, and this one of

grandmother's, and this of Mrs.

Arrasmith's, and this of Aunt

Marget's" and, "Mother, whose is this?"

and so on. These "nine

patches," as they usually were, often contained

a good deal of family history. A little

later in this decade, young women

made quilts of bright colored calicoes,

bought for the purpose and cut

into various intricate designs, which

were sewed down or applied on

white cotton cloth. Months of work were

often sewed into the closely

wrought and elaborately quilted designs.

Such quilts were much

admired and usually put upon the best

beds on great occasions. The

designs often had fanciful names, as

"Mary's Dream," "Morning

Star," "Rose of Sharon,"

and the like. My mother never made any of

these elaborate bed-covers, as she did

not admire them very much.

Another part of a visitor's

entertainment, if it was winter or spring,

was the bringing out of the seed-bag and

dividing up of the

kitchen-garden and flower-seeds. Very

often these seeds were named

from the neighbor who had given the

start of the plants. I remember

hearing my mother say, as she gave some

large white beans with pink

specks on them to a neighbor,

"These are Maria Crane beans." Each

kind of seed was tied up in a piece of

cloth in a little round bunch. I can

Manners and Customs 53

still see myself standing by my

mother's knee, looking on with interest

as she opened the mysterious little

bunches of cloth.

A Marriage Custom

One spring Sunday morning (in 1846 I

have since learned) I was at my

grandmother's in the living-room, with

some of my younger aunts about,

when in came Uncle John Obed and his

bride, Mary Bremerman. They

had just been married at the bride's

home on a farm a mile away, and had

walked over to the groom's home for a

wedding trip. One of my aunts

went to the bride, took off her bonnet

and laid it on the bed, she then

untied her cap strings and said

laughingly, "You shan't have this thing

on," took it off and laid it with

the bonnet. I stared at the lovely pink

cheeks and blue eyes of my new aunt

without understanding anything of

what it all meant. I only knew that

this pretty lady was another aunt

somehow. The simple ceremony at the

house, the bridal cap, the walk to

the husband's home, were all

characteristic of the time. A few days later

the newly married couple went to their

new home in Howard County,

Indiana. Sometimes in the more

well-to-do families, especially if the

couple had the approval of everybody

concerned, there was what was

called an "Infair," a great

dinner to which the relatives of both families

with other neighborhood guests, were

bidden.