Ohio History Journal

ROBERT P. SWIERENGA

Ethnicity and American Agriculture

Ethnic Patterns in Land Settlement

Rural America was never as ethnic as

urban America. The

vastness of the agricultural hinterland

and the traditional family

farm both worked against the formation

and survival of ethnic com-

munities. Nevertheless, ever since

Americans populated the land,

every national and denominational

group, in greater or lesser

degree, is represented in the farming

population. Rural America,

especially the Upper Middle West during

the nineteenth century,

had a remarkable cultural diversity,

traces of which still exist today

in the countryside. Agricultural

historian Allan Bogue has aptly

described the midwestern frontier:

"Farm operators might be

native-born or foreign-born, born to

the English tongue or highly in-

ept in its use. If continental-born,

they might have been raised

among the Rhineland vineyards or

trained to a mixed life of farming

and fishing in Scandinavia, been

emigrants from the grain fields of

eastern Europe or come from many other

backgrounds. If native-

born, they might be Yankee or Yorker,

Kentuckian or Buckeye,

Pennsylvanian or Sucker."1

There were three major ethnic

settlement streams in rural

America-New Englanders, Scotch-Irish,

and Germans-and sev-

eral minor concentrations of

Scandinavians, Canadians, Dutch,

Italians, Czechs, Japanese, and

Mexicans.2 The New England ex-

Robert P. Swierenga is Professor of

History at Kent State University

1. Allan G. Bogue, From Prairie to

Cornbelt: Farming on the Illinois and Iowa

Prairies in the Nineteenth Century (Chicago, 1963), 194-95.

2. Excellent descriptions of these major

settlement patterns are: John L. Shover,

First Majority-Last Minority: The

Transformation of Rural Life in America

(DeKalb, Ill., 1976), 38-50; Frederick

C. Luebke, "Ethnic Group Settlement on the

Great Plains," Agricultural

History, 8 (Oct., 1977), 405-30; Randall M. Miller, "Im-

migrants in the Old South," Immigration

History Newsletter, X (Nov., 1978), 8-14;

Hilldegard Binder Johnson, "The

Location of German Immigrants in the Middle

West," Annals of the Association of American

Geographers, 41 (1951), 1-41;

Frederick Jackson Turner, The United

States, 1830-1850, The Nation and Its Sec-

tions (New York, 1935).

324 OHIO HISTORY

odus, which began in the early

nineteenth century, carried Yankees

across much of the northern United

States. The New Englanders

migrated in stages, first to upper New

York and northwestern Penn-

sylvania (1800s), then to the

"Burned-Over District" of western

New York and northeast Ohio (1820s),

next to southern Michigan or

northern Illinois, southern Wisconsin,

and Iowa (1840s and 1850s),

and finally to Kansas and westward to

Oregon (1870s). The Yankee

frontiersmen usually arrived first,

chose the richest glaciated soils,

and transplanted intact their culture,

churches, and schools.

While the Yankees moved across the

northern tier of the frontier,

the Scotch-Irish in Pennsylvania and

the Carolinas, half a million

strong by the end of the colonial era,

crossed the mountains into

Tennessee and Kentucky.3 From

the Appalachian valley they fanned

out southward across the Gulf Plains

and northward along the

Ohio valley and eventually west of the

Mississippi River into the

hilly, unglaciated regions of eastern

Missouri and southern Iowa.

Typically, the Scotch-Irish spied out

the "loose-dirt" bottom lands

and sandy uplands with which they were

familiar. Unfortunately,

such hilly terrain often contained

inferior soils. The Scotch-Irish

dominated the interior South and Ohio

Valley and stamped this

region with a common ethnic and

cultural identity that was unique

in the nation. In 1850, 98 percent of

the people in the South Central

states were native-born, a higher

proportion than any other region.

The third major ethnic contingent in

rural America was the Ger-

mans, the largest non-English speaking

immigrant group. Fed by a

continuous stream of immigrants from

the colonial period to World

War I, Germans first settled in the

lowland limestone soils of Penn-

sylvania and then after the Revolution

they moved into the fertile

glaciated oak openings and prairies of

the Midwest from northern

Ohio to Kansas and the Dakotas. Texas

also attracted a large con-

tingent, so that by 1900 almost a third

of the Texans were either

German or of Germanic ancestry.

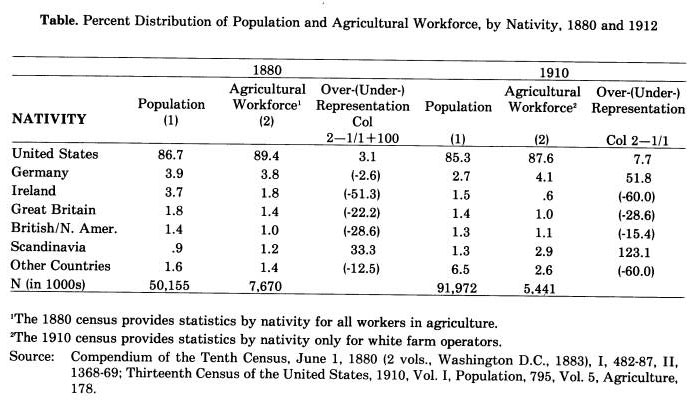

Nationally, according to the 1910

census report, Germans were

"over-represented" in

agriculture by 51.8 percent. (See Table.) They

comprised 2.7 percent of the total

population, but 4.1 percent of the

nation's farmers. Among the 670,000

immigrant farm operators

they were the overwhelming nationality,

with 33 percent. In 1880,

Germans had made up 36 percent of all

farmers, but in proportion to

their total numbers, they were

under-represented in farming by 2.6

percent. Thus, the German presence in

agriculture, as with the

3. James G. Leyburn, The

Scotch-Irish, A SocialHistory (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1962).

|

Ethnicity 325 |

326 OHIO HISTORY

Scandinavians, increased greatly at the

end of the nineteenth cen-

tury.

The Germans preferred to buy

partially-improved farms rather

than open new lands. There were many

exceptions to this

generalization, however. Carl Wittke

reported that Germans

developed 672,000 American farms,

totaling one hundred million

acres. Some of these farms were in

colonial Pennsylvania, where

Germans went to the frontier as

frequently as the Scotch-Irish.4

Wherever they settled, Germans

established the reputation of

developing excellent farms. The German

farmer's regard for his

barn and animals at the expense of his

home and family is prover-

bial in frontier America. Nevertheless,

in the Mennonite county of

Lancaster, stone houses outnumbered

stone barns among Germans,

and small log barns were still the norm

as late as the 1780s. The

large "Swisser" stone barns in

Pennsylvania "Dutch" country ap-

peared only after the farmers had

prospered greatly during the

Revolution.5

The Germans in America comprised three

diverse groups in

language and religion.6 There

were the Anabaptist sects (Volga or

Russo-Germans, Mennonites, Dunkers, and

Amish), Lutherans and

Reformed from northern Germany, and

Catholics from Bavaria and

the south. Each group maintained its

cultural distance and distinc-

tiveness and some, such as the Russians,

spoke languages other

than German. By 1900, the German

immigrant population had

swelled to three million, half of whom

lived in the North Central

states. Many others, such as the

Russo-Germans, clustered

throughout the great plains on land

resembling their native steppes,

where they uniformly introduced hard

winter wheat. Prominent

German areas were Lancaster County,

Pennsylvania; Holmes and

Madison counties, Ohio; Ellis County,

Kansas; Franklin County,

Missouri; and Jefferson County,

Wisconsin. The latter two were 80

percent German in 1900.

Scandinavians numbered more than 1.2

million in 1910 and were

concentrated in the heavily wooded,

forest and lake country of the

Upper Mississippi Valley, which

resembled their homeland. Min-

nesota and Wisconsin were the primary

areas, but scattered

4. Carl Wittke, We Who Built America:

The Saga of the Immigrant (New York,

1946), 208. Wittke describes the

settlement patterns of all of the major immigrant

groups which are described in this and

succeeding paragraphs.

5. James T. Lemon, The Poor Man's

Country: A Geographical Study of Early

Southeastern Pennsylvania (Baltimore and London, 1976), 177.

6. This and the following paragraphs

rely heavily on Wittke, We Who Built

America.

Ethnicity 327

Swedish, Norwegians, Danish, and

Finnish settlements also sprang

up in Iowa, Nebraska, and the Dakotas.

The Norwegians were the

most rural and clannish of the

Scandinavians. As late as 1940, over

half of all midwestern Norwegians lived

on farms or in small

villages. Indeed, they were the only

immigrant group with a lower

proportion of city-dwellers than the

native Americans. Swedes also

led in the conquest of the rolling

prairies. By 1925, they had cleared

and opened an estimated twleve million

acres. The 1910 census

counted 156,000 Scandinavian farm

operators, the second largest

immigrant nationality. Indeed, the

Scandinavians were over-

represented in agriculture by 123

percent in 1918 (Table), which was

more than twice the proportion among

Germans. In 1880, the Scan-

dinavians were the only major

foreign-born group over-represented

in agriculture. The Scandinavians truly

sought after the land.

Other sizeable immigrant groups in the

midwestern farm popula-

tion were Canadians, English, Irish,

Swiss, Dutch, Czechs (Bohe-

mians), and Poles, but no group was

over-represented in proportion

to its total numbers. The Canadians,

English, Irish, and Swiss were

widely scattered in the Upper Great

Lakes, but were especially

strong in Michigan. The Swiss in

northern Wisconsin laid the basis

for the Swiss cheese industry in the

1840s and 1850s. The Dutch

were concentrated particularly in the

lake and woodland regions of

southwestern Michigan, northern

Illinois, and southern Wisconsin,

but several thousand also settled on

the prairies of Iowa and

neighboring states. The Czechs

preferred prairie land; the major col-

onies were in Wisconsin, Nebraska, and

Texas. The latter state had

50,000 Czechs in 1910, mainly farmers.

By that date one-third of all

first generation Czechs in America

followed agricultural pursuits.

Among the southern and eastern European

immigrants, the Czechs

considered farming an ideal way of

life.7 Poles were more inclined to

head for the cities, but some managed

to acquire low-priced

"cutover" timber land in

northern Wisconsin and Minnesota or

abandoned farms in the East. Many began

as farm tenants or

worked in the sawmills, mines, and

quarries as day laborers before

they became land owners. Polish farmers

were less familiar with

modern farming techniques than other

immigrants, and therefore

imitated their neighbors more than

most.

7. In addition to Wittke, We Who

Built America, 409-16, sociological analyses of

specific Czech farming communities are:

Robert L. Skrabanek, "The Influence of

Cultural Backgrounds on Farming

Practices in a Czech-American Rural Communi-

ty," Southwestern Social Science

Quarterly, 31 (1951), 258-62 and Russell Wilford

Lynch, Czech Farmers in Oklahoma: A

Comparative Study of the Stability of a

Czech Farm Group in Lincoln County,

Oklahoma ... (Oklahoma Agricultural

and

Mechanical College Bulletin, 39

[June, 1942]), 107.

328 OHIO HISTORY

The high proportion of northern European

immigrants in rural

midwestern communities was a result of

several factors: the coin-

cidence of their arrival and the opening

of the frontier, the influence

of the Homestead Act of 1862, the

promotional efforts of railroad

agents and immigration bureaus, their

relative prosperity that

enabled them to become farm owners, and

the geographical similari-

ty of the Midwest to their native lands.

Later immigrant groups had neither the

opportunity and capital

to obtain farm land nor the experience

and temperament to confront

a lonely and often hostile environment.

But some southern and

eastern Europeans could be found in the

countryside, especially as

truck farmers near coastal metropolises.

Jewish farmers were pro-

minent in the borscht belt of New York's

Catskills, and among

chicken ranchers in Petaluma, California

and Vineland, New Jersey.

Italians raised fruit and vegetables in

the East, and in the Pacific

Northwest they engaged in dairying,

fruit raising, and built

wineries in California (notably the

Italian Swiss-Colony).

California's Italians competed for prime

farm land with Yugoslavs,

Japanese, Portuguese, Armenians,

Basques, and various northern

European groups. The Portuguese

distinguished themselves as

dairymen in the San Francisco Bay and

Sacramento areas. The

Armenians were prominent in Fresno

County as market gardeners.

One developed the largest fig ranch in

the world.8

The role as seasonal farm laborers of

Orientals, Eastern Euro-

peans, and Spanish-Americans, was also

crucial to agricultural

growth. The Chinese and Japanese

provided the initial pool of

"stoop" labor in the far west

until the Oriental exclusion acts shut

the door between 1882 and 1907.

Filipinos and especially Mexicans

had a near monopoly thereafter, except

during the depression of the

1930s when tens of thousands were

repatriated. The quota law of

1921 did not apply to Mexico and during

the 1920s more than a

million and a half Mexicans crossed the

border. Most settled in the

Southwest, but many moved into the large

midwestern cities of

Chicago, Kansas City, Minneapolis, and

St. Paul. These migrants

on the fruit and vegetable farms of the

sunbelt and the midwest

generally moved northward following the

harvest in three main

streams: from Florida to New Jersey,

Texas to Michigan and Min-

nesota, and up California's Salinas and

Sacramento-San Joaquin

Valleys. The peak year of dependency on

foreign farm workers was

8. Theodore Saloutos, "The

Immigrant Contribution to American Agriculture,"

Agricultural History, 50 (Jan., 1976), 60-62.

Ethnicity 329

1960 when the federal government

admitted 460,000 for harvest

labor.9

The Immigration Commission Reports give

the rural concentra-

tion of the major immigrant groups in

1900. In descending order,

the percentage of foreign-born, male

bread-winners following

agriculture pursuits was Norwegians

fifty, Czechs thirty-two,

Swedes thirty, Germans twenty-seven,

British-Canadians twenty-

two, English eighteen, Irish and French

Canadians fourteen, Poles

ten, Italians six, and Hungarians

three. These percentages would in-

crease an average of five points if

sons of the foreign-born were in-

cluded. Thus, most ethnic groups were more than half

urban at a

time when the national percentage was

45 percent. The census of

1910 further indicates the low

incidence of immigrant farmers: only

12 percent of the nation's farm

operators were foreign-born.10

The geographical distribution of

immigrant farmers was striking-

ly uneven. In 1910, nearly seven out of

ten lived in the Midwest,

where they comprised 20.5 percent of

all farm operators. However,

in Minnesota and North Dakota more than

half of the farmers were

foreign-born, and in Wisconsin and

South Dakota over 30 percent.

The remaining three-tenths were nearly

evenly divided between the

Northeast and Far West regions, but

their small absolute members

were noticed more in the West where

they comprised 23 percent of

all farmers, compared to 11 percent in

the East. A mere 12,000 im-

migrant farmers (.06 percent) settled

in the South because of its

reputedly inferior soils, slavery or

its legacy, and the absence of

friends and relatives. The immigrants,

in short, chose the cities

rather than the countryside, and those

who opted for farming

headed for the midwestern and plains

states.

To what extent climate, ethnic

idiosyncracy, and the pull of

already-established communities

accounted for the distribution of

the immigrant groups is unknown. In

general, however, immigrants

first gathered in and near the large

seaport cities of the Atlantic

Coast, especially in the Middle

Atlantic states, and to a lesser

measure, near the Pacific harbor

cities. They gradually spread out

over the northern, central, and western

sections of the country

wherever transportation and job

opportunities in agricultural and

industry beckoned. Usually the

immigrants clustered around com-

munities of their compatriots. Some

sought certain climates or soil

9. Louis Adamic, A Nation of Nations (New

York and London, 1944), 62-65;

Saloutos, "Immigrant

Contribution," 63-65.

10. U.S. Immigration Commission, Reports

(Washington, GPO, 1911), Vol. 28,

60-62. U.S. Bureau of the Census, 13th

Census, 1910, Vol. 5, Agriculture, 178.

330 OHIO HISTORY

areas that resembled their homelands,

while others preferred urban

life. Many who joined the frontier

movement to the cornbelt and

prairies eventually were swept back into

the cities by the strong ur-

ban tide of the Industrial Revolution.

Cultural Patterns in Farming

Throughout the history of settlement in

the American wilderness,

European immigrant farmers had to deal

with a variety of un-

familiar soils, weather conditions,

vegetation, and terrains. The

fields of Europe had been cleared or

drained for generations, if not

centuries, and land was farmed

intensively and with great variety of

grains, fruits, vegetables, and

livestock. The American frontier,

whether forests or prairies, was

strikingly different. It required that

immigrant farmers adapt themselves to an

alien land.

The degree to which the varying cultural

backgrounds of the im-

migrants influenced their choice of

settlement areas and affected

their farming practices and success rate

has long intrigued

Americans. The literature of rural

history is replete with contem-

porary comments and observations about

the relationship between

cultural background and farming

behavior. Bogue identifies two

key propositions in accounts of

midwestern agriculture.11 The first

is that various ethnic groups, when

learning to farm in America, in-

itially drew upon their particular Old

World skills and modes of

husbandry, thereby introducing specific

crops and farming tech-

niques into American agriculture. The

second hypothesis is that cer-

tain ethnic groups in the same

geographical region farmed for

generations in ways significantly

different from their neighbors,

within the limits of the common

constraints imposed by climate and

soils in each region. He finds the first

proposition more plausible

than the second, but neither has been

sufficiently tested by

systematic research. Only recently have

scholars attempted com-

parative studies of ethnic cropping

patterns, animal husbandry,

technological skills, tenure

differences, and mobility and per-

sistence rates, based upon census

records, tax lists, and estate in-

ventories.12

11. Bogue, Prairie to Cornbelt, 237-38.

12. See, for example, Bogue, Prairie

to Cornbelt 25, 237-40; John G. Gagliardo,

"Germans and Agriculture in

Colonial Pennsylvania," Pennsylvania Magazine of

History and Biography, 83 (1959), 192-218; James T. Lemon, "The

Agricultural

Practices of National Groups in

Eighteenth-Century Southeastern Pennsylvania,"

The Geographical Review, 56 (Oct. 1966), 467-96; David Aidan McQuillan,

"Adapta-

tion of Three Immigrant Groups to

Farming in Central Kansas, 1875-1925" (Ph.D.

Ethnicity 331

Many of the traditional generalizations

about ethnic behavior in

agriculture have been tainted by

stereotypes of "national

character" or frontier

mythologies. Benjamin Rush, Benjamin

Franklin, and other scientists of the

Revolutionary era, for example,

believed that agricultural traditions

of national groups were

distinct. They cited as evidence the

supposed superior farming prac-

tices in the eighteenth century of the

Germans, as compared to their

English and Scotch-Irish neighbors.13

German farmers were literally

described as "earth animals,"

superior to all other nationality

groups in land selection, agricultural

skills, animal husbandry, barn

construction, product specialization,

soil conversion, consumption

habits, and labor-intensive family work

teams.14

The classic statement of this

"national character" genre is from

the pen of Benjamin Rush, the renowned

Philadelphia physician and

one of the early advocates of German

agricultural practices. Ger-

man farms, said Rush in 1789, "may

be distinguished from farms of

other citizens . . . by the superior

size of their farms, the height of

their inclosures, the extent of their

orchards, the fertility of their

fields, the luxuriance of their

meadows, and a general appearance of

plenty and neatness in everything that

belongs to them."15 The

Frenchman J. Hector St. John de

Crevecoeur agreed with Rush.

"Whence the difference arises I

know not, but out of twelve families

of emigrants of each country, generally

seven Scotch will succeed,

diss., University of Wisconsin, 1975);

John G. Rice, Patterns of Ethnicity in a Min-

nesota County, 1880-1905 (Geographical Reports, 4, Norway, University of Umea,

1973); Rice, "The Role of Culture

and Community in Frontier Prairie Farming,"

Journal of Historical Geography, 3 (1977), 155-75; Terry D. Jordan, German Seed in

Texas Soil: Immigrant Farmers in

Nineteenth Century Texas (Austin,

1966); Robert

Ostergren, "Rattvik to Isanti: A

Community Transplanted" (Ph.D. diss., Universi-

ty of Minnesota, 1976); E.D. Ball,

"The Process of Settlement in 18th Century

Chester County, Pa.: A Social and

Economic History" (Ph.D. diss., University of

Pennsylvania, 1973).

13. Lemon, "Agricultural

Practices," 467-68, 495-96; Lemon, Best Poor Man's

Country, xiv.

14. The "earth animals" quote

is from Adolph Schock, In Quest of Free Land

(Assen, Netherlands, 1964), 131. Major

traditional stereotypical studies are: Walter

M. Kollmorgan, "The Pennsylvania

German Farmer," in Rudolph Wood (ed.), The

Pennsylvania Germans (Princeton, 1942), 27-55; Stevenson Whitcomb Fletcher,

Pennsylvania Agriculture and Country

Life, 1640-1840 (Harrisburg, 1950);

Richard

H. Shryock, "British Versus German

Traditions in Colonial Agriculture," Mississip-

pi Valley Historical Review, 26 (1939), 39-54. Similar perspectives regarding

nineteenth-century German farmers are

Joseph Schafer, "The Yankee and Teuton in

Wisconsin," Wisconsin Magazine

of History, 6 (1922), 125-45, 261-79, 386-402; Ibid.,

7 (1923), 3-19, 148-71; William H.

Gehrke, "The Ante-Bellum Agriculture of the Ger-

mans in North Carolina," Agricultural

History, 9 (July, 1935), 143-60; Marcus Lee

Hansen, The Immigrant in American

History (Cambridge, Mass., 1940), 61-63;

Saloutos, "Immigrant

Contribution," 45-67.

15. Quoted in Saloutos, "Immigrant

Contribution," 48.

332 OHIO HISTORY

nine Germans, and four Irish.. "16 Methodical,

frugal, and in-

dustrious, German farmers rapidly

achieved self-sufficiency, accord-

ing to these accounts. They raised

other cereals to supplement their

principal cash crop, wheat, and perfected the

Conestoga wagon and

bred the Conestoga horse to carry their products to

market. Scotch-

Irish farmers, on the other hand, were

said to mine their land and

leave livestock and machinery to

weather the winter elements un-

protected. James Lemon is correct in

viewing the origins of such at-

titudes as an English colonial import,

stemming from a set of

stereotypes held by Englishmen about

the superiority of German

peasants and the inferiority of Celtic

peoples in agricultural prac-

tices.17 Once fixed, the

beliefs were reinforced by late-nineteenth

century ethnic societies and

filiopietistic historians.

In marked contrast to the ethnic

apologists, frontier historian

Frederick Jackson Turner, the most

respected scholar in the early

twentieth century, completely rejected

the nationalist views of

Rush, Franklin, and other

European-oriented historians. The fron-

tier, for Turner, was a democratic

melting pot, the great economic

leveller, a place that destroyed the

European "cultural baggage" of

the immigrant pioneers. The land and

not the culture of the im-

migrant was the significant factor in

acculturation. After a very

short period of settlement, immigrant

farmers became in-

distinguishable from American-born

neighbors in the operation of

their farming businesses.18

Several modern studies, based upon the

manuscript population

and agricultural census lists, seem to

confirm Turner's thesis of

rapid assimilation and cultural

conformity among immigrant

farmers. In a study of early settlement

in a Wisconsin county

(Trempealeau), Merle Curti compared the

socioconomic structure

and relative economic success of all

major nativity groups, for the

census years 1850, 1860, 1870, and

1880. Initially, Americans and

English-speaking foreign-born farmers

owned better land, had more

implements and livestock, obtained

higher crop yields, and were less

transient than the Continental-born

farmers. This was largely due

to their lateness of settlement and

inadequate financial resources.

16. J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur, Letters

from an American Farmer and

Sketches of Eighteenth-Century America

(New York, 1963), 79. This is quoted

in

Crevecouer's famous essay, "What is

an American?"

17. Lemon, "Agricultural

Practices," 493-94; Lemon, Poor Man's Country, 17-18.

18. Frederick Jackson Turner, "The

Significance of the Frontier in American

History," American Historical

Association, Annual Report for the Year 1893

(Washington, G.P.O., 1894), 199-227.

Turner elaborated his thesis in The Frontier in

American History (New York, 1920).

Ethnicity 333

Continental-born farmers arrived after

the Anglo-Americans had

picked the choice prairie lands.

Gradually, however, the poorer im-

migrant groups-Irish, Poles, and

Germans-made steady gains

and within a generation their farm

valuations approached the level

of the Americans. The only group to lag

behind was the

Norwegians, who arrived last and

selected hilly, wooded slopes

resembling their homeland. Even this

difference was only in degree,

not in kind; and Curti stressed the

essential similarity of all ethnic

groups in frontier Wisconsin.19

In his study of pioneer farming in

Illinois and Iowa, Bogue

specifically addressed the issue of

whether ethnic groups in the

same region farmed differently over a

considerable period of time.

The conventional wisdom was that

Germans and Swedes raised

more pigs than did Yankees. Charles

Towne and Edward Went-

worth, in their history of the pig,

state that these two nationality

groups pulled themselves "out of

the red" with a "combination of

pluck, perspicacity, and pigs. .. .

Less skilled in the management

of horses, sheep, and beef cattle than

the English and native

Americans, they concentrated with

dogged tenacity on their

hogs."20 In his

statistical analysis of hog production in Hamilton

and Bremer counties in northcentral

Iowa in 1880, Bogue found

that foreign-born farmers actually

owned fewer swine than native

farmers, a direct contradiction of the

prevailing wisdom. In their

crop production, however, immigrant

farmers conformed to the

general observation. Immigrants raised

more wheat and less corn

than natives and they hired more farm

hands, an indication that

they practiced a more intensive type of

agriculture.21 Thus, the

native-born farmers in Iowa anticipated

the future corn-hog sym-

biosis more than did immigrant farmers,

but neither group differed

substantially.

Additional midwestern studies bear out

this conclusion of

semblance. Seddie Cogswell compared

livestock valuation and the

number of farm animals in six eastern

Iowa counties (1850-1880)

and concluded that "for the most

part there was essential similarity

between the farms of native-and foreign-born. . . .

[They] did not

differ very much, either in the numbers

of the various farm animals

or in their mix."22 The immigrant

farmers had a slightly lower in-

19. Merle Curti, The Making of an

American Community: A Case Study of

Democracy in a Frontier County (Stanford, Cal., 1959), 80-83, 91-97, 179-97.

20. Quoted in Bogue, Prairie to

Cornbelt 237.

21. Ibid., 238.

22. Seddie Cogswell, Jr., Tenure,

Nativity and Age as Factors in Iowa

Agriculture, 1850-1880 (Ames, Iowa, 1975), 75, 78.

334 OHIO HISTORY

vestment in livestock, but this was

more than offset by a greater

amount of machinery. Donald Winters

likewise found that native or

foreign-born tenants in Iowa were not

distinguishable in terms of

rental arrangements, farm practices, or

success rates.23

In a pathbreaking study, Robert

Ostergren compared cropping

patterns and livestock enterprises

among Old Americans, Germans,

and Scandinavian farmers in Isanti

County, Minnesota, in 1880. He

concluded that cultural factors had a

minimal impact on crop deci-

sions compared to the overrriding

effects of geographic and en-

vironmental conditions in the

community. Only in the case of

secondary crops such as oats and

livestock such as sheep did

cultural traditions have an impact.24

The economic status of the

various ethnic groups in Isanti

measured by land and wealth data

likewise revealed few striking

differences not explained by length of

occupance.25 Ostergren

traced one group of Isanti Swedes back to

their Old Country parish of Rattvik and

compared their farming

practices before and after migration.

This thoroughly innovative

technique revealed that in Rattvik

barley had been the primary

crop, with oats a secondary crop. In

Minnesota, by contrast, wheat

(which had never been raised in Sweden)

was the primary crop and

oats a secondary one. The Rattvik

colonists transplanted their in-

stitutions, Ostergren concluded, but

not their farming practices.

"When it came to making a living

it seems that the immigrants

were faced with little choice but to

adapt as quickly as possible to

the American system." "In

fact," said Ostergren, "there is little

evidence that there ever was much

resistance to the dictates of the

new environment and the local market

economy. The situation was

so different from home, that one

probably did not even seriously

contemplate farming in the same

manner."26

David McQuillan used a different

technique to assess the adapta-

tion process among immigrant groups in

the more arid region of cen-

tral Kansas. He selected three ethnic

groups-Swedes, Mennonites,

and French-Canadians-and compared

farming practices not only

between the groups but within the

groups by selecting one township

in which the group was clearly dominant

and one township in which

the particular immigrant group was a

minority among native-born

farmers. Rural segregation of the

ethnic groups had no significant

impact on farming practices, McQuillan

concluded. Only the Men-

23. Donald L. Winters, Farmers

Without Farms: Agricultural Tenancy in

Nineteenth-Century Iowa (Westport, Conn., 1978), 77, 88, 135.

24. Ostergren, Rattvik to Isanti, 107-21.

25. Ibid., 121-28.

26. Ibid., 140.

|

Ethnicity 335 |

|

nonites diverged from the American norm by operating smaller farms of higher value, by diversifying their crop and livestock enter- prises, and by owning debt-free farms rather than rentals.27 Religious values may have been the determining factor in the case of the Mennonites, although McQuillan does not pursue this intrigu- ing lead. In brief, the immigrant farmers of frontier Wisconsin, Illinois, Iowa, and Minnesota adjusted rapidly and without apparent dif- ficulty. From the earliest period of settlement, they made greater gains than the native-born, obtaining a proportionate share of the land and developing unsurpassed commercial farming businesses. Instead of the common picture of the relatively "poor" and traditional-bound immigrant farmer, the census research indicates that measured by farm size, livestock, crops, and machinery, Euro- pean immigrants quickly adopted the best practices of the region and they had the financial resources to do so. At least at the broad level of the nationality group, economic differentials did not mark immigrant farmers from natives. This midwestern picture is repeated in Terry Jordan's detailed comparison of German and Anglo-American farmers in Texas (1850-1880). Although the Germans clung to Old World cultural traits that made them distinctive for generations among Texas

27. McQuillan, "Adaptation of Three Immigrant Groups to Farming." |

336 OHIO HISTORY

farmers, in other important ways they

"became Southerners almost

from the first." The Germans were

more attracted to the soil and

committed to commercial agriculture.

They farmed with greater in-

tensity and productivity, were less

mobile, and had a higher rate of

landownership. They diversified more by

actively pursuing market

gardening near the major Texas towns, by

producing wine and

white potatoes (in a sweet potato

region), by cultivating small

grains, and by using mules instead of

horses as draft animals. But

the similarities between Germans and

southern-born farmers were

"even more striking than the

differences." The Germans were im-

itators rather than innovators. They

introduced no new major crops

or livestock practices, but rather began

cultivating the three

southern staples-corn, cotton, and sweet

potatoes. They adopted

the southern farmstead architecture and

open range system, with

no barns for wintering stock. They

neither dunged their fields nor

stall-fed their livestock.28

In a German settlement in the Missouri

Ozarks dating from the

1890s, Russell Gerlach compared agricultural

land use and crop pro-

duction in 1972 in four sample counties

that contained clearly de-

fined German and non-German farming

regions.29 As in Texas, more

Germans were full-time farmers and they

worked their land more in-

tensively, but their crops, farm size,

yield per acre, and tenancy

rates did not appreciably differ from

that of the Old Stock

Americans who had emigrated from

Appalachia to the Ozarks in the

last century. The major difference is

cultural. Germans are more

traditional and share a deeper

commitment to an agrarian way of

life than the native Americans, but

their farming behavior is barely

distinguishable.

Jordan suggests a four-class typology of

the "survival

tendencies" of imported

agricultural systems by immigrant

groups.30 (1) Old Country

traits never introduced, such as the Texas

Germans' failure to dung fields and

winter livestock in barns. (2)

European traits introduced but not

successfully implemented. For

Texan Germans these included

viticulture, European fruit trees, the

farm village plan and communal herding

on the West Texan plains,

and small grain production in the east

Texas cotton belt. (3) Euro-

pean traits that survived only the first

generation. These included

28. Jordan, German Seed in Texas

Soil, chaps. 4-6. The quotes are on p. 195.

29. Russell L. Gerlach, Immigrants in

the Ozarks: A Study in Ethnic Geography

(Columbia and London, 1976).

30. This paragraph and the four

following are summarized from Jordan, German

Soil in Texas Soil, 194-203.

Ethnicity 337

small-scale farm operations, German

farmstead structures, and the

free-labor system in east Texas. By the

1850s, some Germans in

East Texas were purchasing slaves. (4)

Long-lived traits. Texas Ger-

man farmers were distinguishable for

generations by their labor-

intensive, highly productive, stable,

diversified agriculture.

The determinant factors in these various

outcomes were the

physical and cultural-economic

environments. The mild Texas

climate, for example, obviated the need

for large barns and winter

quartering of livestock. Without barns,

manure was lost. The

economic milieu likewise encouraged

immigrants to adapt farming

practices of the region because those of

the native Southerners were

proven superior. For example, Germans

shifted from small family

farms to large-scale commercial

agriculture common to the region.

Moreover, those traits that did survive,

either intact or modified,

such as intensive farming methods,

cheese-making, and cultivating

white potatoes, were those that did not

interfere with or undermine

the economic viability of Texas

agriculture.

Many of these surviving traits were

curiously absent in the

earliest years of settlement but emerged

later in what Jordan calls a

"cultural rebound." The

initial shock of adjustment to a new en-

vironment apparently inclined immigrants

to ape indigeneous

American practices. But gradually this

initial "artificial" assimila-

tion was reversed and unique dormant

traits reappeared. The Ger-

mans were an alien group in Texas

confronting an agricultural socie-

ty that had evolved over two hundred

years. The uniqueness almost

guaranteed the survival of their

"Europeanness."

Whether the "built-in" traits

of agricultural immigrants from

northwestern and central Europe suvived

in American farm com-

munities depended largely on the

disimilarity to their Old Country

environment. The more alien the cultural

environment, the more

defensive and persistent the group.

Since the southern United

States was not as congenial to

European-born farmers as the north-

ern regions, immigrants in the South

retained their distinctiveness

more than did their compatriots in the

North. On the other hand,

German wheat farmers in Kansas, Rhine

winegrowers in California,

and Norwegian dairymen in Wisconsin

risked losing their ethnic

identity quickly because they blended in

with their neighbors from

the beginning.

The rapid assimilation of immigrant

farmers was due to more

than a familiar cultural environment.

Before leaving Europe, im-

migrants often purchased crude farming

manuals and guide books

to ease their introduction to America.

They also sought direct con-

338 OHIO HISTORY

tacts with American neighbors to learn

proven farm methods in the

area. Many unmarried young men and women

"hired out" to

Americans as field hands and domestics.

If fellow-ethnics had

previously settled the region, newcomers

naturally sought their aid

and served "apprenticeships"

under them. Despite the rapid ac-

culturation, foreign-born farmers, of

course, always faced a greater

adjustment than natives.

The Texan farmers of German ancestry

today still retain some

distinctive social-cultural traits, but

Jordan concluded that dif-

ferences in agricultural practices are

largely "invisible," if they per-

sist at all. As farmers and ranchers,

the Germans in Texas are

businessmen first and foremost; they are

ethnics only in the farm-

house, in church, and in social clubs.31

This finding agrees with

Bogue's assessment of midwestern ethnic

farmers: Cultural dif-

ferences "were more apparent than

real-most obvious in food

ways, dress, and lingual traits, and

less important when the farmer

decided on his combination of major

enterprises."32

The census research summarized here is

seminal. It provides the

first solid evidence regarding ethnic

patterns in agriculture. But all

of these studies suffer from two

limitations, which are inherent in

the census sources. The first is that

all farmers of a given nationali-

ty are lumped together, without taking

account of local and regional

differences in the motherland. The

censuses only record the country

of birth, of course, and it would be a

herculean task to link the cen-

sus with foreign records at the local

level. Yet in nineteenth century

Europe, farming practices, life styles,

and even languages often dif-

fered widely between two adjacent

provinces in the same country, or

even between two parishes in the same

province. Secondly, the early

studies slight the importance of

religious group differences, again

because the censuses do not report

religious or denominational af-

filiation. Thousands of close-knit,

church-centered, ethnic com-

munities dotted the landscape of rural

America a century ago.

These homogeneous clusters of people

often had common origins in

the Old Country and they deliberately

sought to create isolated set-

tlements in hopes of preserving their

cultural identity and retaining

the mother tongue for generations to

come. Such cohesive sectarian

communities differed greatly from

settlements composed of a mix-

ture of main-line "church"

groups, even if all were Protestant.33

31. Ibid., 203.

32. Bogue, Prairie to Cornbelt, 238.

33. This is the perceptive approach of

Marianne Wokeck in her dissertation ir

progress at Temple University. See

Marianne Wokeck, "Cultural Persistence and

Adaptation: The Germans of Lancaster

County, Pennsylvania, 1729-76," in Pau

Ethnicity 339

There are several recent micro-studies

that take into account the

parish background of American immigrant

farmers. These are

highly rewarding and suggestive of the

direction of future research

in agricultural history. John Rice

studied farming patterns in a six-

township area of frontier Minnesota

(Kandiyohi County), which was

settled by Swedes, Norwegians, Irish,

and Americans from the

East.34 Each of the

nationality groups was diverse in origin, except

for one group of Swedes who came from

the same parish-Gagnef in

Dalarna Province. Two other Swedish

settlements were more

diverse, comprising people from many

parishes, yet all from the

same provinces. Moreover, each of the

three subnational Swedish

culture groups was affiliated with the

three major church com-

munities in the sample townships. Thus,

Rice was able to compare

agricultural practices of Swedish

cultural groups defined at the na-

tional, provincial, and parish levels.

Rice's findings, based on both Swedish

and American sources,

reveal that farmers from all the

nationality groups, except the

Swedes of Gagnef parish, were similar

in their cropping patterns,

livestock holdings, persistence rates,

and economic status. All the

groups concentrated on wheat. The

Scandinavians (including the

Norwegians) raised more livestock,

especially sheep, than the Irish

and Americans, and the Swedes were more

persistent. But the

Gagnef parishioners stand out as

unique. They retained their oxen

as draught animals into the 1880s, long

after the other farmers in

the area had switched to horses. The

Gagnef community was the

most stable by far, and it prospered

economically, advancing from

the poorest of the Swedish settlements

to the wealthiest. In sum,

the agricultural experience of the

church-centered Gagnef group,

transplanted en masse from Dalarna,

differed markedly from the

neighboring immigrant settlements,

including those of Swedes and

Norwegians. Religion and its cultural

trappings, not nationality per

se, determined farming behavior among

Minnesota Swedes.

The impact of religion on immigrant

farmers was not unique to

Swedes. A century early in southeastern

Pennsylvania, sectarian

"plain folk," Mennonites from

the Rhine Valley and Switzerland,

Friends (Quakers) from England and

Wales, and German Baptist

"Dunkers" and Moravian

Brethren similarly occupied and used the

land differently than immigrants from

mainline European chur-

Uselding, ed., Business and Economic

History Papers Presented at the Twenty-

Fourth Annual Meeting of the Business History

Conference (Urbana, Ill., 1978), n.p.

34. The findings of this paragraph and

the next are from Rice, "The Role of

Culture" and "Community in

Frontier Prairie Farming," 166-75.

340 OHIO HISTORY

ches-Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican, and

Presbyterian. The sect

groups valued discipline and

cooperation. The Moravians lived com-

munally in agricultural villages,

following the European "open-

field" system, but the Mennonites

and Quakers lived on family

farms. The sects were tightly clustered

geographically, owned the

most valuable farms, and were least

transient. Although most

farmers in Lancaster and Chester

counties were involved in general

mixed agriculture with an emphasis on

wheat, the Mennonites and

Quakers farmed more intensively, sowed

more wheat acreage, and

possessed more livestock than other

national and denominational

groups.35 Thus, in a

relatively homogeneous agricultural region, the

only significant differences in farming

behavior derived from

religious, rather than ethnic origins.

The seven Amana villages in

Iowa and numerous Spanish-American

peasant villages in New

Mexico, the latter antedating the

Mexican war of independence

from Spain in the 1820s, provide

additional examples of religiously-

based communities that to this day use

the open-field system of

agricultural settlement. In all of

these communities, behavioral

distinctions in farming can be

determined only through microscopic

local studies.

Contributions

Not only did immigrant farmers bring to

America a willingness to

confront an alien land, they also made

specific contributions to

agriculture.36 The most

general contribution of farmers from the ad-

vanced nations of northern Europe was

simply their dedication to

farming as a way of life and their

skill in farm techniques, animal

husbandry, and cropping practices. The

extent to which the ideal-

ized family-sized farm has survived the

forces of modernization is

largely due to the determination of

third and fourth generation im-

migrants to maintain their traditional

life style and values.

In animal husbandry, immigrant farmers

throughout the north-

ern part of the country consistently

set the standard for livestock

winter care, utilization of manure, and

selective breeding. The Penn-

sylvania Germans by the late eighteenth

century had demonstrated

the necessity of huge, functional

barns, but native-born farmers

were exceedingly slow to emulate them.37

As late as 1849, a Dutch

35. Lemon, Poor Man's Country, 63-64,

81-85, 174, and passim; Lemon,

"Agricultural Practices,"

467-96.

36. The best survey is Saloutos,

"Immigrant Contribution," 45-67. The 91 notes

also provide an extensive bibliography.

37. Perry Wells Bidwell and John I.

Falconer, History of Agriculture in the North-

ern United States, 1620-1860 (Washington, D.C., 1925), 107-08, 122-23.

Ethnicity 341

immigrant in central Iowa reported to

relatives in the Province of

Friesland: "Americans do not have

barns. . . As a rule the cattle

here are not as heavy as in Friesland,

and as far as I can see, this is

caused by the fact that they are left on

their own during the winter.

Calves are not placed in the stable and

no colts are taken inside, so

livestock suffers terribly."38

From their firsthand knowledge, im-

migrants, especially those from the

British Isles, introduced in the

half century after Independence the

improved varieties of animals

developed in Europe, such as the Spanish

Marino sheep and English

cattle and hogs-the Herefords, Shorthorns,

Durhams, and Devons.

Indeed, as with the Industrial

Revolution of the nineteenth century,

English agricultural reforms of the

eighteenth century came a

generation or two earlier than in

America and provided the impetus

for change, especially in livestock.39

Immigrant farmers also contributed to

the introduction of new or

improved varieties of plants and crops

that were so important in the

development of American agriculture. In

the Carolina and Georgia

tidewater region in the eighteenth

century, French settlers led in the

introduction of the more esoteric

agricultural products such as

grapes, silk-worm and mulberry trees,

olives, and indigo.40 The

Frenchmen, Lewis Gervais, Lewis St.

Pierre and Pierre Legaux, suc-

cessfully transplanted native French

grapevines and established the

vineyard industry in North America.

Similarly, Andrew Deveaux

was the provincial indigo expert whose

efforts raised the quality of

American indigo to that of the best

French product. Farmers of

English-stock in New England and the

Middle Colonies, meanwhile,

introduced the cultivation of grasses

and legumes for animal forage

and hay. The fact that early clovers

were simply called "English

grass" testifies to their origin.

Notable nineteenth century plant imports

were Grimm alfalfa and

Turkey Red wheat. A German immigrant to

Carver County, Min-

nesota in 1857, Wendelin Grimm, brought

a twenty-pound bag of

alfalfa seed from his homeland. Over a

number of years the alfalfa

acclimatized to withstand winterkill

until it became the prime

38. Robert P. Swierenga, ed., "A

Dutch Immigrant's View of Frontier Iowa"

(Sjoerd Aukes Sipma, Belangryke

Berigten uit Pella, in de Vereenigde Staten van

Noord-Amerika [Important Reports from Pella, in the United States of

North

America], 1849), Annals of Iowa, 3rd

Series, 38 (Fall, 1965), 95, 89.

39. Rodney C. Loehr, "The Influence

of English Agriculture on American

Agriculture," Agricultural

History, 11 (Jan. 1937), 3-15.

40. Arthur H. Hirsch, "French

Influence on American Agriculture in the Colonial

Period With Special Reference to

Southern Provinces," Ibid., 4 (Jan., 1930), 1-9. See

also Arthur P. Whitaker, "The

Spanish Contribution to American Agriculture,"

Ibid., 3 (Jan., 1929), 1-14.

342 OHIO HISTORY

forage crop of the Northwest.

Agricultural historians have stated

that "its permanence, enormous

yields, high protein content,

economy as a crop, and value as a soil

builder and weed throttler is

almost without parallel in plant

history."41 No wonder that farmers

called it the "everlasting clover

seed!" Mennonite settlers from the

Crimea introduced Turkey Red wheat in

south-central Kansas in

1873, and this hardy winter wheat and

other durum varieties

became within a generation the great

cash crop of the semi-arid

regions of the northwestern plains. Ten

years earlier, Russian im-

migrants had brought durum wheat to the

Dakotas. In the 1890s,

other Russian peasants brought to the

United States from their

native steppes the seeds of kabanka and

arnautska wheat and also

special rye and sunflower seeds, all of

which became widely

cultivated on the plains.42 The

white potato is another plant that ad-

ded variety to the American diet because

of the persistent efforts of

German and Irish farmers to cultivate

it.

Farmland reclamation was another

immigrant specialty, especial-

ly among those groups who arrived

penniless after the great

homesteading era had ceased. "The

foreign-born take the marginal

land," Edmund de S. Brunner

declared, "hoping that their energy

and muscle will overcome other

handicaps."43 The Poles, Russians,

and Finns were notable examples. Between

1870 and 1920, three

million Polish peasants migrated to the

United States. They were

unskilled and poor but willing to work

hard and accumulate sav-

ings. With these meager savings some

750,000 Poles purchased

farms abandoned by New Englanders in

Massachusetts, the Con-

necticut Valley, and upstate New York.

Others acquired lower quali-

ty lands in the Midwest and Texas. By

dint of toil and thrifty

management, Poles restored numerous

farms to a productive state.

By 1940, some 30,000 Russian immigrants

were also in the land,

many in the East on abandoned farms.44

The Polish and Russian

story is repeated among the Finns, who

were too poor to buy choice

farms.45 By working first as

the lowest-paid laborers in the mills,

41. Saloutos, "Immigrant

Contribution," 66; Peter C. Marzio, ed., A Nation of

Nations: The People Who Came to

America as Seen Through Objects and

Documents Exhibited at the

Smithsonian Institution (New York,

1976), 148.

42. Adamic, Nation of Nation, 155.

43. Edmund de S. Brunner, Immigrant

Farmers and Their Children (Garden City,

N.Y., 1929), 44.

44. Wittke, We Who Built America, 421,

428-29; Saloutos, "Immigrant Contribu-

tion," 56-57.

45. A. William Hogland, "Finnish

Immigrant Farmers in New York, 1910-1960,"

in O. Fritrof Ander, ed., In the Trek

of the Immigrants: Essays Presented to Carl

Wittke (Rock Island, Ill., 1964), 141-55.

Ethnicity 343

mines, and forests of the East coast or

Midwest, they slowly ac-

cumulated enough capital to buy the

"cutover" lumber lands of

northern Wisconsin, Michigan, and

Minnesota. These areas had

thin, rocky soil and required much

back-breaking labor to root out

the stumps before the land could be

farmed. In 1920, 90 percent of

the Finns in Wisconsin agriculture were

in the cutover area. Other

Finns purchased abandoned farms in the

old agricultural regions of

New England and New York. The Finnish

historian, A. William

Hogland, has described one such group

of several hundred Finns

who in 1910, at the behest of local

real estate agents, began settling

on abandoned land in New York's hill

country. The farms sold for

$500 to $3,000. The Finns eventually by

1950 numbered over five

hundred and dominated the agriculture

of three townships. Most

had little farming experience; yet they

developed profitable dairy

farms and during the 1930s turned to

large-scale poultry raising.

The Finns played a major part in the

agricultural revival in New

York after World War I.

Although most immigrant farmers brought

less capital with them

to the frontier than the native-born

farmers, at least one group of

Italian farmers in California, led by

Amadeo Peter Giannini, found-

ed the Bank of Italy which subsequently

became the Bank of

America. The credit operation of the

Bank of America had a pro-

found impact on the agricultural

development of the state. An im-

migrant from Russian Poland, David

Lukin, likewise strengthened

the marketing mechanism of American

farmers by protecting their

export markets in Europe through the

creation of the International

Institute of Agriculture (now the

United Nations Food and

Agriculture Organization). This

organization served as a clearing

house of information on European crop

production and prices,

which enabled American farmers to

compete in the world market.46

Conclusion

The forces of change in modern life are

breaking down the local

ethnic and cultural distinctions in

American agriculture; they are

tending to "homogenize rural

society." But in the past local condi-

tions varied greatly and the process of

acculturation was uneven.

Unfortunately, the ethnic variety in

rural America remains an

enigma because the subject of ethnicity

and agriculture is virtually

unexplored. Marcus Lee Hansen's 1940

list of "suggestive subjects

for investigation" remains intact.

Hansen urged the study of "the

46. Saloutos, "Immigrant

Contribution," 66-67.

344 OHIO HISTORY

immigrant as an outright [land]

purchaser, the rise of the hired land

to ownership; the immigrant as renter

or mortgaged debtor; occupa-

tion of abandoned farms by any race;

the different racial customs in

providing for the second generation;

the immigrant as a market

gardener, cotton planter or tobacco

grower, as a fruitman, rancher

or ordinary prairie mixed-farmer; the

employment of farm hands

and older sons in lumbering, ice

cutting and other seasonal labor;

the attitude toward improvements and

scientific farming."47 Com-

parative local studies of specific

ethnic groups, considering topics

such as these, would greatly enlarge

our understanding of rural

America and the impact on ethnic groups

of the forces of moderniza-

tion since the early days of

settlement.

47. Hansen, Immigrant in American

History, n200.