Ohio History Journal

PHILIP A. GRANT, JR.

Congressional Campaigns of

James M Cox, 1908 and 1910

On September 16, 1908, the Democrats of

the Third Congressional District of Ohio

held their biennial convention at

Middletown and by acclamation nominated James

M. Cox of Dayton as their candidate for

the House of Representatives. Thus began

the public career of the only Ohioan

ever nominated for the presidency by the

Democratic party. The aggressive

campaign waged by Cox for a seat in Congress

inaugurated a twelve year period of

sustained political activity, culminating in his

candidacy for President of the United

States.

Thirty-eight years of age, Cox was the

publisher of the Dayton Daily News and

one of southwestern Ohio's most

illustrious citizens.1 The year 1908 was indeed an

opportune time for Cox to launch his

political career. The Democrats of the Third

District were optimistic that year

largely because the Republican opposition was

split into two irreconcilable factions,

one of which was led by Charles W. Bieser,

Montgomery County Republican chairman,

and the other by freshman Congressman

John E. Harding of Middletown.

Bieser had been responsible for denying

renomination to Harding, and the latter

was to retaliate by running for

reelection to Congress in 1908 as an independent.

Replacing Harding as the Republican

nominee was one of Bieser's most loyal

supporters, State Representative William

G. Frizell of Dayton. The Third District

consisted of Montgomery, Butler, and

Preble counties, and was marginal in political

complexion.2 Since the

district was almost evenly divided between Republicans and

Democrats, it was imperative for each

party to maintain maximum harmony within

its ranks. In 1906, when the Republicans

had been united, Harding had easily

defeated his Democratic challenger by a

plurality of 1,730 votes: 24,567 (49.4%)

to 22,837 (46.0%). The Socialist and

Prohibitionist candidates had received 1,896

and 393 votes respectively.3

Although nominated on September 16, Cox

did not launch his congressional

1. For an autobiographical account of

Cox's early life see James M. Cox, Journey Through

My Years (New York, 1946), 3-53.

2. During the sixteen years of its

existence, the district had been represented by five congress-

men: three Democrats and two

Republicans. Each party had won four regular congressional

elections during this period, while the

Democrats had won the only special election. Indicative

of the district's marginal character was

the fact that four of these elections had been decided

by less than 202 votes.

3. Ohio, Annual Report of the

Secretary of State, 1906, p. 153.

Mr. Grant is associate professor of

history at Pace College Westchester in Pleasantville, New

York.

|

|

|

campaign until nearly two weeks later. Altogether his campaign lasted five weeks, during which he made approximately three dozen public appearances. The bulk of Cox's speeches were delivered in Montgomery and Butler counties, while only four days were spent in sparsely populated Preble County. Indeed Cox reserved the final two weeks of the campaign almost exclusively for political activities in the Dayton area, a decision probably motivated by the fact that Dayton and the other nearby communities in Montgomery County accounted for more than sixty percent of the district's population.4 From the outset of his campaign Cox heartily praised both the 1908 Democratic National Platform and the presidential candidacy of William Jennings Bryan. Ap- plauding the platform as the "greatest declaration of popular rights since the Declaration of Independence," Cox eagerly volunteered explanations of its major planks.5 Steadfast in his loyalty to Bryan, Cox stressed that his party's presidential nominee had for many years been among the nation's most fervent advocates of political and economic reforms. Throughout the campaign Cox concentrated on what he believed to be the vital issues of the day, portraying himself as a progressive Democrat completely in accord with the official pronouncements of his party.6 Frequently charging that the dominant Republican party had failed to solve the serious problems confronting the nation, Cox was sharply critical of the record of the recently adjourned Sixtieth Congress. He blamed the Republicans for the Panic

4. According to the 1900 census, the population figures were as follows: Montgomery County 130,146; Butler County 56,870; Preble County 23,713. Abstract of the Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900 (Washington, 1904), 166. 5. The entire text of the platform may be found in The Campaign Text Book of the Demo- cratic Party of the United States, 1908 (Chicago, 1908), 7-17, 220-227. 6. Daily News (Dayton), October 6, 8, 23, 27, 29, 30, 1908. |

6

OHIO HISTORY

of 1907,7 and on at least two

occasions inferred a causal relationship between

previous economic disruptions and the

presence of the Republican party in power.

Denouncing the shortcomings of past GOP

platforms, Cox tried to persuade the

voters of the Third District that the

Republicans had pursued a policy of negativism

in national affairs.8

There is abundant evidence to warrant

the conclusion that Cox considered the

tariff question the paramount issue in

the congressional campaign of 1908. Histor-

ically the Democratic party had opposed

the protective tariff, and in 1908 the

Democrats had adopted an unequivocal

plank on tariff revision in their national

platform.9 Cox and many other

Democrats sensed that the Republicans would be

especially vulnerable at this time

because of their refusal to repeal the Dingley Tariff

act of 1897.10 In his first major

campaign speech at Dayton on September 30, Cox

severely criticized the "stupendous

privileges" accorded to American industry under

the Dingley tariff. Thereafter he

availed himself of every opportunity to identify

the Republican party with a senseless

and discriminatory system of tariff protec-

tionism. On several occasions Cox

advanced the argument that the protective tariff

perpetuated the existence of monopolies.

He also charged that some American

manufacturers found it necessary to

operate factories abroad, because of retaliatory

measures other nations had imposed

against the United States, and that domestic

manufacturers were charging the American

farmer more for agricultural implements

than they were selling such implements

to customers in foreign countries. In speech

after speech Cox not only assailed the

justification for continuing the tariff but also

pointed out its detrimental effects on

the welfare of both the worker and the

consumer.11

With the sole exception of the tariff

question, Cox devoted more attention to the

need of guaranteeing bank deposits than

to any other issue. Referring to the adverse

effects of the Panic of 1907, Cox at the

beginning of the campaign stressed that

he and the Democratic party were

"committed absolutely" to guaranteeing bank

deposits.12 Cox argued that

this was necessary in order to prevent runs on banks

7. A detailed account of the Panic of

1907 may be found in William C. Schluter, The Pre-

War Business Cycle, 1907 to 1919 (New York, 1923), 13-34.

8. Daily News (Dayton), October

3, 6, 8, 10, 21, 28, 29, 1908. Daily News-Signal (Middle-

town), September 29, October 13, 1908.

9. Stressing that "during years of

uninterrupted power no action whatever has been taken

by the Republican Congress to correct

the admittedly existing tariff inequities," the Democrats in

1908 approved the following statement:

"We favor immediate revision of the tariff by the

reduction of import duties. Articles

entering into competition with trust-controlled products

should be placed on the free list and

material reductions should be made in the tariff upon the

necessities of life, especially upon

articles competing with such American manufactures as are

sold abroad more cheaply than at home;

and gradual reductions should be made in such other

schedules as may be necessary to restore

the tariff to a revenue basis." Campaign Text Book, 10.

10. A thorough analysis of the Dingley

tariff may be found in Frank W. Taussig, The Tariff

History of the United States (New York, 1931), 325-360.

11. Daily News (Dayton), October

1, 10, 14, 20, 23, 27, 30, 31, 1908; Evening Journal

(Hamilton), October 9, 1908; Daily

News-Signal (Middletown), October 17, 1908.

12. A portion of the 1908 Democratic

platform read as follows: "The panic of 1907, coming

without any legitimate excuse when the

Republican party had for a decade been in complete

control of the Federal Government,

furnishes additional proof that it is either unwilling or in-

competent to protect the interests of

the general public. It has so linked the country to Wall

Street that the sins of the speculators

are visited upon the whole people ...." The Democrats

"pledged" that national banks

would "be required to establish a guarantee fund for the

prompt payment of the depositors of any

insolvent national bank, under an equitable system

which shall be available to all State

banking institutions wishing to use it." Campaign Text Book,

223-224.

Cox's Campaigns 7

and assure the American people of a more

stable financial system. He undoubtedly

felt that the average citizen was

genuinely concerned with protecting his savings,

and he was also aware that many

residents of Ohio's Third Congressional District

had suffered financial losses either

directly or indirectly as a result of the Panic of

1907. Apparently optimistic that popular

sentiment strongly favored measures to

protect depositors, Cox flatly predicted

that within five years all banks would guar-

antee deposits as a precondition to

their survival.13

In addition to expressing himself quite

forcefully on the need for tariff and banking

reform, Cox endorsed the passage of a

constitutional amendment providing for a

federal income tax.14 Indicating

his grave concern over the maldistribution of wealth

in the United States, Cox deplored the

fact that the Republican majority in Congress

had declined to pass a joint resolution

in behalf of an income tax amendment.

Because a small minority of the

population owned the vast majority of the nation's

property, Cox insisted that it was

necessary for economic and social reforms to

emanate directly from the people.15

During the campaign Cox voiced

unqualified support for the objectives of the

labor movement. He emphasized the labor

plank in his party's national platform, a

plank generally acknowledged to be the

most comprehensive ever adopted by a

major American political party.16 Specifically

Cox urged the establishment of a

Department of Labor, and promised that,

if elected to Congress, he would introduce

legislation calling for general

employers' liability.17

Among the other issues discussed by Cox

during the 1908 campaign were business

monopolization, railroad regulation, and

direct election of United States Senators.

Expressing alarm over the growth of business consolidation,

Cox warned that

monopolies were stifling opportunities

for the nation's young people.18 On the

question of railroads he took pride in

the fact that, unlike the Republicans, the

Democrats had demanded rate regulation

as early as the presidential campaign of

1896.19 Cox also urged the adoption of a

constitutional amendment providing that

United States Senators be elected

directly by the citizens of their respective states.20

On all of these matters Cox was

affirming support for planks included in the 1908

13. Daily News (Dayton), October

1, 8, 20, 22, 23, 30, 31, 1908; Daily News-Signal (Middle-

town), October 3, 1908; Evening

Journal (Hamilton), September 30, October 9, 1908.

14. In 1908 the Democrats adopted the

following plank: "We favor an income tax as part

of our revenue system, and we urge the

submission of a constitutional amendment specifically

authorizing Congress to levy and collect

a tax upon individual and corporate incomes, to the

end that wealth may bear its

proportionate share of the burdens of the Federal Government."

Campaign Text Book, 12.

15. Daily News (Dayton), October 6, 8, 31, 1908.

16. In 1908 the Democrats urged that

labor organizations be treated "with rigid impartiality"

in all judicial proceedings, declared

that there should "be no abridgement of the right of wage

earners and producers to organize for

the protection of wages and the improvement of labor

conditions," endorsed the

"eight-hour day on all government work," pledged the enactment of

a federal law "for a general

employers' liability act covering injury to body or loss of life of

employes," and vowed to support

legislation "creating a Department of Labor, represented

separately in the President's

Cabinet." Campaign Text Book, 12.

17. Daily News (Dayton), October

1, 10, 22, 29, 1908; Evening Journal (Hamilton), October

9, 1908.

18. Evening Journal (Hamilton),

October 24, 1908.

19. Daily News (Dayton), October

6, 27, 1908.

20. Ibid., October 1, 1908.

|

8 OHIO HISTORY

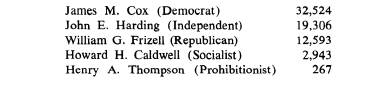

Democratic Platform.21 Throughout the duration of the 1908 congressional campaign there is no record that Cox ever referred to either of his two opponents, Frizell and Harding. Realizing that his opposition was divided between regular Republicans led by County Chairman Bieser and independent Republicans loyal to Congressman Harding, Cox undoubt- edly felt that it would be prudent to concentrate on issues rather than personalities. Indeed the spokesmen of the rival Republican factions, largely ignoring Cox, re- peatedly indulged in personal villification against one another. By the end of the campaign a multitude of charges and countercharges had been leveled by both Bieser's and Harding's supporters, all of which accentuated the irreconcilable diff- erences of opinion within the Republican party of the Third District.22 The election was held on November 3, and the early returns indicated an unmistakable Democratic trend in Cox's district. By the following day it was evident that the Democrats had emerged victorious in all the major political races. Both Bryan and Judson Harmon, the Democratic presidential and gubernatorial candidates, carried the district by comfortable margins. The entire Democratic ticket carried Butler County, while the Democrats won all but two of the nineteen offices at stake in Montgomery County. Winning all three of the district's counties, Cox was handily elected to Congress. The final vote was as follows:23 |

|

|

|

Although Cox received more votes than the combined total of his two major opponents and probably would have been elected even if the Republicans had been united, he was the beneficiary of the strong electoral performances by Bryan and Harmon.24 The unity in Democratic ranks was in sharp contrast to the obvious Republican dissention. Cox, undoubtedly encouraged by the internal strife plaguing the local Republican party, conducted a statesmanlike campaign, stressing what he believed to be issues of vital consequence to the citizens of the Third District. He had proved to be an energetic campaigner and would enter the House of Represent-

21. Denouncing private monopolies as "indefensible and intolerable," the Democrats in 1908 demanded enactment of legislation "to make it impossible for a private monopoly to exist in the United States." The Democrats also favored "efficient supervision and rate regulation" of railroads, recommending that the Interstate Commerce Commission be authorized to undertake physical valuation of railroad property. They also endorsed election of United States Senators "by direct vote of the people." Campaign Text Book, 14, 11. 22. Herald (Dayton), October 10, 12, 15, 1908; Journal (Dayton), October 1, 9, 13, 14, 16, 21, 28, November 1, 1908; Republican-News (Hamilton), September 19, October 1, 2, 5, 22, 30, 1908. 23. Bryan, carrying Butler and Montgomery counties, outpolled his Republican opponent, William Howard Taft, by a margin of 33,491 to 30,908. Harmon, a former Attorney-General of the United States, defeated his Republican challenger, Andrew Harris, 36,636 to 28,348. Annual Report of the Secretary of State, 1908, p. 185, 187, 189, 194, 222, 235, 239, 272, 468. 24. In 1904 Judge Alton Parker, the Democratic presidential candidate, had polled 24,122 votes in the Third Congressional District. This total accounted for only 42.4% of the major party vote of that year. By contrast Bryan's 33,491 votes in 1908 accounted for 52.1% of the major party vote. Harmon received the largest plurality ever recorded by a Democratic guber- natorial candidate in the history of the Third District with 35,636 votes. |

Cox's Campaigns 9

atives at one of the most exciting times

in American political history.

On March 15, 1909, the first session of

the Sixty-First Congress assembled, at

which time James M. Cox was sworn in as

a member of the House of Representatives.

Between the opening ceremonies and the

adjournment of the first session on August

5, he would have the responsibility of

casting votes on a number of important issues.

The three foremost issues considered

during these months were internal reform of

the House, federal taxation, and tariff

revision.

For several years prior to 1909 many

Democrats, including Cox, had severely

criticized the excessive influence

wielded by the incumbent Speaker of the House,

Joseph G. Cannon.25 Shortly

after the House assembled on March 15, Representative

Champ Clark, Democratic floor leader,

offered a resolution designed to curtail

Cannon's powers. In addition to

depriving the Speaker of the right to appoint the

personnel of most committees, this

resolution provided that the powerful Rules

Committee be elected by the entire House

membership and authorized a study to

determine ways of revising and

simplifying existing House procedures. Cox supported

the Clark resolution, and, although the

proposal was rejected by a vote of 203-180,26

it was quite evident that a substantial

minority was dissatisfied with the structure

of the House under Cannon.

The controversy over a federal income

tax had been raging since the United States

Supreme Court in 1895 had invalidated a

congressional income tax statute on

constitutional grounds. Subsequent to

this historic judicial decision, a campaign

had been launched in behalf of an income

tax amendment to the Constitution. In

his quest for a seat in Congress, Cox

had pledged to support a federal income tax,

and on July 12, 1909, he joined an

overwhelming majority of his colleagues in the

House in voting to submit an income tax

amendment to the states.27

The most bitterly debated issue of the

first session of the Sixty-First Congress

was tariff revision. Cox, as previously

mentioned, had repeatedly urged tariff reform

in his 1908 campaign. Fifteen days after

taking his oath as a member of the House

Cox delivered his maiden speech,

denouncing the protective tariff as seriously harmful

to the economy of Ohio's Third

Congressional District and strongly advocating that

many of the necessities of life be

placed on the free list. The tariff proposal presented

to the House, authored by Representative

Sereno Payne, was assailed by the Demo-

crats as unduly protectionist in

character. Consequently, Cox and nearly all his

Democratic colleagues unsuccessfully

opposed passage of the Payne bill. When this

bill emerged from a House-Senate

conference committee it was even more distasteful

to the Democrats, largely because of

numerous amendments sponsored by Chairman

25. Charging that the House had come

under the Speaker's "absolute domination," the

Democrats in their 1908 platform had

adopted the following statement: "We demand that

the House of Representatives shall again

become a deliberative body, controlled by a majority

of the people's representatives and not

by the Speaker, and we pledge ourselves to adopt such

rules and regulations to govern the

House of Representatives as will enable a majority of its

members to direct the deliberations and

control legislation. Campaign Text Book, 221.

26. Congressional Record, 61

Cong., 1 Sess., 21-22; Champ Clark, My Quarter Century of

American Politics (New York, 1920), II, 270-272; Cox, Journey Through

My Years, 64-65; Post

(Washington, D.C.), March 16, 1909.

27. A scholarly account of the income

tax question between 1895 and 1909 may be found

in Randolph E. Paul, Taxation in the

United States (Boston, 1954), 40-97; House of Repre-

sentatives, Report on the resolution

(S.J. Res. 40) proposing an amendment to the Constitution,

July 12, 1909; Congressional Record, 61

Cong., 1 Sess., 4440; Post (Washington, D.C.), July 13,

1909.

10

OHIO HISTORY

Nelson Aldrich of the Senate Finance

Committee.28 Cox was among the congressmen

opposing acceptance of the Payne-Aldrich

conference report. A motion to recommit

the conference report lost by the narrow

vote of 186-191, and the report itself was

approved by the somewhat larger margin

of 195-183.29 The tariff debate of 1909

had been long and acrimonious, and Cox

and other Democrats both in the House

and throughout the nation were expected

to focus attention on the deficiencies of

the Payne-Aldrich Tariff act in the

congressional elections of 1910.30

The House had been so preoccupied with

the tariff question that committee

assignments were not announced until the

final day of the first session. It was a

foregone conclusion that Cox, as a

freshman congressman, would be appointed to

relatively minor committees. Thus, it

was not surprising Cox was assigned to the

District of Columbia and Alcoholic

Liquor Traffic committees. Indeed he welcomed

his assignment to the District of

Columbia committee, because one day each week

was always reserved for floor debate on

matters relating to the needs of the nation's

capital.31

After spending several months in Ohio,

Cox returned to Washington for the opening

of the second session of the Sixty-First

Congress. The second session began on

December 6, 1909, and continued until

June 25, 1910. Cox and his colleagues were

undoubtedly mindful that they faced

reelection campaigns in 1910, and the second

session was characterized by unusual

partisanship. Among the major issues facing

the members were the revived controversy

over reform of House rules, establishment

of a postal savings system, and

enlargement of the powers of the Interstate Commerce

Commission.

Although the Democrats had failed to

reduce the powers of the Speaker in 1909,

criticisms of Cannon's domination of the

House persisted. An inkling that Cannon's

influence was waning occurred on January

7, 1910, at which time an amendment was

offerred by Nebraska's Representative

George W. Norris, providing a special com-

mittee to investigate the Department of

the Interior that would be elected by the

House rather than one appointed by the

Speaker. Supported by Cox and the bulk

of his fellow Democrats, the Norris

amendment was approved by a vote of 149-146.32

Ten weeks later Norris introduced a

resolution, the principal object of which was to

assure that the members of the Rules

Committee be elected by the House itself.

After three days of heated debate and

parliamentary wrangling, the House, rebuffing

Cannon, approved the Norris resolution

by a margin of 191-156. Cox not only voted

28. Congressional Record, 61

Cong., 1 Sess., 260-263, 1300-1302; Cox, Journey Through

My Years, 61-63; Post (Washington, D.C.), March 31, April

10, 1909; House of Representatives,

Conference Report on the bill (H.R.

1438) to provide revenue, equalize duties, encourage

the industries of the United States, and

for other purposes, July 30, 1909; Nathaniel W. Stephen-

son, Nelson W. Aldrich (New York,

1930), 346-361.

29. Congressional Record, 61 Cong., 1 Sess., 4754-4755; Post (Washington,

D.C.), August

1, 1909.

30. Analyses of the Payne-Aldrich act

may be found in the following articles: George M.

Fisk, "The Payne-Aldrich

Tariff," Political Science Quarterly (March 1910), 35-68; Frank

W. Taussig, "The Tariff Debate of

1909 and the New Tariff Act," Quarterly Journal of Eco-

nomics (November 1909), 1-38; H. Parker Willis, "The

Tariff of 1909," Journal of Political

Economy (November 1909), 589-619, (January 1910), 1-33.

31. Congressional Record, 61

Cong., 1 Sess., 5091-5093; Cox, Journey Through My Years, 59.

32. Norris, a dissident Republican from

Nebraska, was one of Cannon's foremost critics.

The purpose of his amendment was to

prevent Cannon from appointing a committee composed

primarily of supporters of the Interior

Department's policies. Congressional Record, 61 Cong.,

2 Sess., 404-405; George Norris, Fighting

Liberal (New York, 1945), 109-110; Post (Washing-

ton, D.C.), January 8, 1910.

Cox's Campaigns 11

for passage of the Norris resolution but

also supported an unsuccessful attempt to

depose Cannon as Speaker.33

For many years various bills calling for

the establishment of a postal savings

system had been pending before the

House. Cox had advocated such a system while

campaigning for a seat in Congress,

consistent with a plank contained in the 1908

Democratic Platform.34 Although

Cox and virtually all other congressional Democrats

favored postal savings as a matter of

principle, they objected to the proposal advanced

by the Republican majority in the House,

primarily because of a provision that the

system would be administered by a board

of trustees rather than the local post

offices. When this proposal reached the

floor of the House, Cox initially supported

a Democratic substitute for the bill and

then voted to recommit the entire measure to

the Post Offices and Post Roads

committee. Apparently feeling, however, that the

bill contained some constructive

features, Cox, unlike most of his fellow Democrats,

voted for it on final passage.5

Cox was vitally interested in

strengthening the power of the Federal Government

to regulate interstate commerce. In 1910

the House considered the Mann bill,

enlarging the government's jurisdiction

over railway operations and authorizing the

creation of a Commerce Court. Fearing

that the proposed Commerce Court would

be overly conservative in its rulings,

Cox and the vast majority of House Democrats

voted to recommit the Mann bill, and,

after the recommital motion failed by a margin

of 157-176, voted against the bill's

passage.36 This legislation, however, was con-

siderably liberalized in the Senate,

thereupon becoming known as the Mann-Elkins

bill. Consequently, Cox and nearly all

other House Democrats urged acceptance of

the Senate version of the bill, but a

motion to that effect was defeated 156-162.

Instead, the bill was sent to a House-Senate

conference committee. Convinced that

too many of the bill's beneficial

provisions had been deleted by the conference com-

mittee, the Democrats futilely opposed

the measure in its final form.37

In addition to voting on a wide variety

of national issues, Cox was involved in a

number of matters directly related to

the welfare of Ohio's Third Congressional

33. Congressional Record, 61

Cong., 2 Sess., 3436-3439; Charles R. Atkinson, "The Com-

mittee on Rules and the Overthrow of

Speaker Cannon," (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Colum-

bia University, 1911), 103-120; Norris, Fighting

Liberal, 113-119; Post (Washington, D.C.),

March 18, 19, 20, 1910.

34. Although preferring legislation to

guarantee bank deposits, the Democrats in 1908 had

adopted the following plank: "We

favor a postal savings bank if the guaranteed bank can not

be secured, and that it be constituted

so as to keep the deposited money in the communities

where it is established. But we condemn

the policy of the Republican party in proposing postal

savings banks under a plan of conduct by

which they will aggregate the deposits of rural

communities and redeposit the same while

under government charge in the banks of Wall

Street, thus depleting the circulating

medium of the producing regions and unjustly favoring

the speculative markets." Campaign Text Book,

15.

35. House of Representatives, Report on

the bill (S. 5876) to establish postal savings de-

positories, June 7, 1910; Congressional

Record, 61 Cong., 2 Sess., 7765-7768; Edwin W. Kem-

merer, Postal Savings: An Historical

and Critical Study of the Postal Savings Bank System of

the United States (Princeton, 1917), 21-49; Post (Washington,

D.C.), June 10, 1910.

36. Congressional Record, 61

Cong., 2 Sess., 6031-6033; Post (Washington, D.C.), May 11,

1910.

37. Congressional Record, 61

Cong., 2 Sess., 7577-7578; Post (Washington, D.C.), June 8,

1910; Conference Report on the Bill

(H.R. 17536) to create a commerce court, and to amend

the act entitled "An Act to

regulate commerce," approved February 4, 1887, as heretofore

amended, and for other purposes, June

14, 1910; Congressional Record, 61 Cong., 2 Sess., 8485;

Frank H. Dixon, "The Mann-Elkins

Act, Amending the Act to Regulate Commerce," Quar-

terly Journal of Economics (August 1910), 593-633.

12 OHIO

HISTORY

District. In 1910 he addressed his

colleagues on conditions at the Soldiers' Home in

Dayton, complaining that the amount of

money appropriated for the subsistence of

the veterans residing there was woefully

inadequate. Cox persuaded the House to

increase a proposed appropriation for

the Soldiers' Home by $253,000. He was also

instrumental in securing House approval

for the construction of a new federal build-

ing in Dayton, a facility which at the

time of its completion would include a central

post office and a United States District

Court.38

Renominated for the House of

Representatives in 1910, Cox formally began his

reelection campaign by delivering a

lengthy speech at the Coliseum in Hamilton on

October 7. The 1910 congressional

campaign was remarkably similar to Cox's

initial political venture two years

earlier. As in 1908, this campaign lasted approxi-

mately five weeks and was confined

primarily to Montgomery and Butler counties.

Also, consistent with the policy he had

established in 1908, Cox concentrated on a

few major issues and never referred to

either of his two opponents by name.

Unlike 1908, Cox in 1910 was an

incumbent congressman. Rather than merely

criticizing the Republican opposition,

he constantly reminded his constituents of the

votes he had cast during his term in the

House. Indeed Cox made his voting record

the basis of his reelection campaign,

citing the principal questions considered by the

House and explaining why he had

supported or opposed each.

As in 1908, Cox insisted that the tariff

was the paramount issue of the campaign.

At virtually every public appearance the

congressman staunchly defended his opposi-

tion to the Payne-Aldrich tariff.

Charging that the act was a thoroughly protectionist

measure, he frequently alleged a causal

relationship between the prevailing high duties

and the rising cost of living.

Accordingly, Cox complained that the 1909 statute

adversely affected the economic welfare

of the Third District's farmers, workers, and

consumers. Stipulating that the tariff

should only be high enough to compensate for

differences in production costs at home

and abroad, the legislator maintained that

protective tariff constituted an

indirect taxation. He also reiterated his conviction

that the high Republican tariff provoked

foreign nations to adopt retaliatory policies

which forced American manufacturers to

remove their operations to other countries.

He also reaffirmed that the tariff was

the foremost reason for the growth of monopolies

in the United States. Repeatedly

criticizing the Republican party for ignoring its 1908

platform pledge in behalf of tariff

revision, Cox inferred that the GOP was irrevocably

committed to the protective tariff. As a

remedy for the problems occasioned by the

high tariff, he strongly endorsed the

negotiation of reciprocity treaties with foreign

nations. Judging by the priority status

which Cox accorded to the tariff issue and the

fervor with which he assailed the

Payne-Aldrich act, he undoubtedly was convinced

that his constituents were deeply

concerned with this question.39

Next to the tariff issue Cox devoted an

unusual amount of attention to the income

tax question. Although Congress in 1909

had approved an income tax amendment

to the Constitution, only nine states

had ratified this amendment by October 1910.

Cox and many other Democrats had urged

passage of a congressional income tax

bill, assuming that the Supreme Court

would likely reverse its 1895 decision declaring

such a law unconstitutional. Cox

asserted that prompt approval of income tax legisla-

38. Congressional Record, 61

Cong., 2 Sess., 6177-6183, 6990-6998, 7003-7006; Cox, Journey

Through My Years, 60-61, 65-66; United States Statutes at Large,

1909-1911, XXXVI, 680, 694,

704, 1370.

39. Daily News (Dayton), October

7, 11-29, 1910; Evening Journal (Hamilton), October 7,

11-15, 18, 19, 1910; Daily

News-Signal (Middletown), October 8, 11-14, 17, 18, 1910.

Cox's Campaigns 13

tion would provide additional revenue

for the Federal Government and thus facilitate

tariff reduction. He also declared that

such legislation would "compel hidden and in

many instances inactive wealth to pay

its proportionate share of public expenses."

Finally, Cox concluded that the existing

federal corporation tax was ultimately paid

by the consumer, because corporations

generally increased the prices of their products

in order to secure necessary money for

their taxes.40

Although Cox scrupulously refrained from

indulging in personalities when cam-

paigning against his opponents in the

Third Congressional District, he availed himself

of every opportunity to excoriate the leaders

of the Republican party in the House and

Senate. On many occasions he sharply

criticized Speaker Cannon and Senator Aldrich.

Aware that Cannon's image had become

considerably tarnished, Cox charged that the

Speaker had devised tyrannical rules for

the avowed purpose of stifling majority

sentiment in the House. The Ohioan made

it quite clear that Cannon's influence

could be eliminated only if the

Democrats gained control of the House of Representa-

tives. As for Aldrich, Cox assailed the

Senator for his role in perpetuating the pro-

tective tariff and resisting tax reform.

Cox often reminded his audiences that Cannon

and Aldrich were the two dominant

figures in Congress, and that, as a consequence

of their leadership, the Republicans had

remained insensitive to the pressing needs

of the time.41

During the 1910 campaign Cox also

directed his attention to such issues as postal

savings, railroad regulation, and

conservation. He expressed pride in having voted

for the establishment of a postal

savings bank, arguing that this institution would not

only protect the savings of workers and

farmers but would also eliminate fears of

periodic financial panics.42 Explaining

the votes he had cast on the Mann-Elkins bill,

he emphasized his belief in effective

federal regulation of railway operations. Finally,

Cox severely criticized the

conservationist policies of the Republican party, specific-

ally citing President William Howard

Taft's controversial dismissal of an ardent

conservationist, Gifford Pinchot, as

Chief of the Forestry Service.43

Cox's principal opponent, Republican

George R. Young of Dayton, waged an

unusually brief campaign and made

comparatively few public appearances.44 Young's

position on the tariff was diametrically

opposed to that espoused by Cox, as the

Republican aspirant praised both the

principle of tariff protectionism and the Payne-

Aldrich act. Young also attempted to identify

the leadership of the Republican party

with sound money and national

prosperity. Although he firmly supported his party

on all substantive issues, Young did on

several occasions indicate his strong dis-

approval of Speaker Cannon.45

40. Daily News (Dayton), October

7, 13, 18, 19, 22, 24, 1910; Evening Journal (Hamilton),

October 13, 19, 1910; Daily

News-Signal (Middletown), October 13, 18, 1910.

41. Daily News (Dayton), October

11, 12, 14, 15, 17-19, 26, 28, 31, November 1, 3, 1910;

Evening Journal (Hamilton), October 11, 15, 19, 1910; Daily

News-Signal (Middletown),

October 11, 12, 14, 18, 1910.

42. Daily News (Dayton), October

11, 14, 24, 1910; Evening Journal (Hamilton), October

14, 15, 19, 1910; Daily News-Signal (Middletown),

October 14, 18, 1910.

43. Daily News (Dayton), October

13, 14, 31, 1910; Evening Journal (Hamilton), ibid.;

Daily News-Signal (Middletown), ibid.

44. In 1910 Cox was also challenged by

two minor opponents, Harmon Evans, Socialist,

and Richard E. O'Byrne, Independent.

45. Journal (Dayton), October 11,

18, 23, 25, 27, 28, 1910; Republican-News (Hamilton),

October 10, 21, 22, 27, 28, November 2,

1910.

|

14 OHIO HISTORY

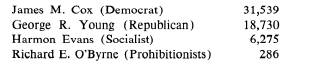

The 1910 elections were held on November 8. The Democrats won a smashing nationwide victory, gaining fifty-six seats in the House of Representatives, adding nine seats in the United States Senate, and securing a majority of the governorships in the various states. The Democratic trend was nowhere more evident than in Ohio's Third Congressional District. Cox, again carrying all three of the district's counties, was easily reelected to Congress. The election statistics were as follows:46 |

|

|

|

Cox's margin of 12,809 votes over his Republican opponent was a very impressive plurality. His total accounted for 62.7% of the major party vote, whereas four years earlier the Democratic congressional candidate had polled only 48.2% of the major party vote. Cox undoubtedly was genuinely pleased that such a sizeable majority of the Third District's voters had responded so favorably, both to his performance as a member of the House of Representatives, and to the issues which he had effectively championed in the 1910 campaign. Although appointed to the prestigious Committee on Appropriations at the open- ing of the Sixty-Second Congress in April 1911, Cox was soon thereafter to begin his quest for the governorship of Ohio. Nominated for governor by acclamation on June 15, 1912 and elected to the first of three terms as Ohio's chief executive on November 5, 1912, he was to climax his distinguished public career in 1920 as the Democratic candidate for President of the United States. A political novice at the time he launched his initial congressional campaign in September 1908, Cox by November 1910 had been overwhelmingly reelected to his second term in the House of Representatives and thus became the leading contender for the governorship of the nation's third largest state. Indeed the twenty-six month period between September 1908 and November 1910 constituted the political apprenticeship of James M. Cox.

46. The Democrats won 228 of the 390 seats in the House, thus guaranteeing the end of Cannon's reign as Speaker. Although the Republicans retained nominal control of the Senate, that body was to be dominated during the next two years by a coalition of forty-one Democrats and approximately ten progressive Republicans. Harmon was reelected governor of Ohio by 100,377 votes, and the Democrats also elected governors in such important states as Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and Indiana. Altogether the Democrats would have twenty-six of the nation's forty-six governorships. Annual Report of the Secretary of State, 1910, p. 168. |