Ohio History Journal

DIALECT DISTRIBUTION AND SETTLEMENT

PATTERNS

IN THE GREAT LAKES REGION

by ALVA L. DAVIS

Assistant Professor of English,

Western Reserve University

The study of dialect distribution in

the eastern United States

and in the secondary settlement areas

of the Great Lakes Region

has now reached a point where it is

possible to show some interesting

correlations between the linguistic

features and the settlement

patterns of these regions. It is

simple, perhaps even obvious, to say

that when large, homogeneous groups of

people migrate to new

territories, they take with them the

speech patterns of their old

communities and that these speech

patterns will be gradually modi-

fied as various cultural influences are

brought to bear on them.

However, the validity of any

correlation depends upon a solid

foundation of extensive and painstaking

research, rather than on

generalities, and for this particular

problem, such research materials

are provided by the collections of the Linguistic

Atlas of the United

States and Canada.1

The Linguistic Atlas, which

proposes to be a comprehensive

survey of American English, was begun

in 1931 under the director-

ship of Professor Hans Kurath, then at

Brown University. In that

year the first of the regional atlases,

The Linguistic Atlas of New

England, got under way. Upon completion of the records for New

England, field work was extended to the

Middle Atlantic and South

Atlantic states and these records were

finally completed during the

spring of 1949. The Linguistic Atlas

of New England2 has been

published, and the Middle Atlantic and

South Atlantic materials

1 This paper is limited to a discussion

of Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.

For an account of the Wisconsin data,

see Frederic G. Cassidy, "Some New England

Words in Wisconsin," Language, XVII

(1941), 324-339. The name "Great Lakes

Region" has been applied to this

area.

Other articles based on Atlas field

work in the region are Albert H. Marck-

wardt, "Folk Speech in Indiana and

Adjacent States," Indiana Historical Bulletin,

XVII (1940), 120-140; "Middle

English o in the American English of the Great

Lakes Area," Papers of the

Michigan Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters, XXVI

(1941), 56-71; "Middle English WA

in the Speech of the Great Lakes Region,"

American Speech, XVII (1942), 226-254.

2 Hans Kurath, ed. (6 vols., Providence,

1939-43).

48

Dialect Distribution in the Great

Lakes Region 49

are on file at the University of

Michigan, where they are to be

edited and prepared for publication.

The technique employed by the Linguistic

Atlas is modeled

upon the personal interview methods

developed by European lingu-

ists. After a careful analysis of the

geography and history of the

region to be surveyed, the director of

the project plots the com-

munities for investigation. These

communities are spaced so as to

furnish a balanced sampling of speech

forms in the area, the number

of the communities varying with the

complexity of the region. A

trained phonetician then visits each

community and interviews native

speakers, asking several hundred

standardized questions designed to

bring out regional and social

differences in dialect. Each interview

requires about eight hours and is

conducted in such a way that

the informant uses his normal

pronunciation, grammar, and vocab-

ulary. According to the plan of the Linguistic

Atlas, two speakers

are chosen from each community, one a

representative of the oldest

generation with relatively little

education, and another of the middle

age group (ordinarily from fifty to

sixty years old) with con-

siderably more formal education and

wider social contacts. Oc-

casionally college educated informants

are interviewed to represent

the cultured speech of the area. In the

eastern states-from Maine

to Florida--over 1,600 field interviews

have been completed. The

geographical spacing of the communities

permits the plotting of

the informants' responses on maps so

that regional dissemination

of speech forms can be related to

topographical, historical, and

cultural influences. By using

informants from different age groups

and from varying social backgrounds

much useful data can be ob-

tained about innovation, obsolescence,

and prestige values of speech

forms.

Since 1937 The Linguistic Atlas of

the North Central States,

under the supervision of Professor

Albert H. Marckwardt of the

University of Michigan, has been making

steady progress.3 Work

in this region was begun with an

exploratory survey of Ohio, In-

3 This

atlas includes the five states named above (footnote 1) plus Kentucky.

The research in this area has been made

possible by grants from the Rackham Founda-

tion of the University of Michigan, from

the University of Illinois, University of

Wisconsin, Western Reserve University,

Ohio State University, and the Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Society.

50 Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Quarterly

diana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and

Michigan, limited to ten field records

in each state. This initial survey was

completed in 1940 and the

project was then expanded to cover from fifty to

seventy records per

state. The additional field work has

already been done in Wisconsin

and Michigan and is currently being

carried on in Illinois and Ohio.

The historical background for dialect

distribution in the Great

Lakes Region is well known. The

settlement patterns for Ohio,

Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan are

easily traced, partly because the

region is new, comparatively speaking,

and partly because a wealth

of information on the subject is

available.4 Three main streams of

migration entered the area. The

southernmost and earliest of these

used the Ohio River system and peopled

the lands within easy reach

of the river and its tributaries. This

group of settlers was for the

most part from the Middle Atlantic

states and the hill regions of

the old slave states. In the north the

important avenue of approach

was the Great Lakes. Although some New

Englanders, following

Moses Cleaveland's party of 1796, had

settled in the Connecticut

Western Reserve, the opening of the

Erie Canal in 1825 started the

great land rush into that area, made up

principally of Yankees

from New York state. This migration,

which reached its peak in

the 1840's and 1850's, completed the

settlement of the Ohio counties

bordering Lake Erie and filled up most

of Michigan and northern

Illinois. The third general migration

was the overland movement,

especially along the National Road. The

Conestoga wagon carried

Pennsylvanians into Ohio and westward,

and Buckeyes and Hoosiers

themselves joined in this search for

cheap land.

Within the Great Lakes Region are two

important small areas

distinctive in the composition of their

population: in southeastern

Ohio, the Marietta colony, founded in

1788 by the Ohio Company,

from Massachusetts, and in northwestern

Illinois, the Lead Region

settled in the 1820's by miners from

all parts of the country.5

4 Information concerning settlement is

available in such works as Frederic L.

Paxson, History of the American

Frontier 1763-1893 (Boston, 1924); Lois K.

Mathews, The Expansion of New England

(Boston, 1909); Beverley W. Bond, Jr.,

The Foundations of Ohio (History of

the State of Ohio, edited by Carl

Wittke, I,

Columbus, 1942); Solon J. Buck, Illinois

in 1818 (Springfield, 1917). Tables I and

VII, U. S. Census, 1870: Population, are

of great value for determining the geo-

graphical extent of these settlements.

5 The Lead Region also includes

southwestern Wisconsin. See Cassidy, loc. cit.,

Dialect Distribution in the Great

Lakes Region 51

Even though much field work is still to

be done in the Great

Lakes Region, the present data is

adequate for a preliminary com-

parison to the Eastern findings. The

handiest material for such a

comparison is the folk vocabulary, the

everyday words of life around

the house and farm.

On the basis of the vocabulary variants

of the Eastern Atlas

records, Professor Kurath has

discovered three main dialect areas,6

differing considerably from the traditional

three-fold Eastern,

Southern, and General American

classification.7 The Eastern records

show a Northern area including New

England, New York, the

northern half of New Jersey and

approximately the northern quarter

of Pennsylvania; a Midland area including

the rest of Pennsylvania

and New Jersey, parts of Delaware and

Maryland, and the moun-

tainous South, beginning at the Blue

Ridge; and a Southern area

consisting of the coastal South from

Delaware to Florida.

None of these areas is completely

uniform, but divided into

several subareas. The North is composed

of Eastern New England

(roughly from the Connecticut River)

Western New England

and Upstate New York, the Hudson

Valley, and metropolitan New

York. The Midland may be divided

conveniently into two large

subareas: North Midland for most of

Pennsylvania and northern

West Virginia, and South Midland for

the speech of the mountain

area to the south. The South

(identified most easily by loss of post-

vocalic r) contains many subareas, many

of them centering around

such cities as Richmond, Charleston,

and Savannah.

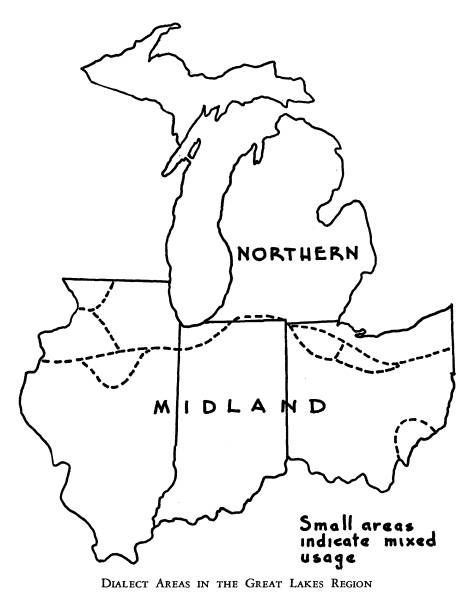

The general patterns which folk terms

make in the Great Lakes

Region are shown on the accompanying

map.8 The "Yankee" settle-

ment is consistent in using Northern

words, and the area to the

south of it is almost without exception

Midland. Between the two

326. Foreign population settlements,

such as that at Holland, Michigan, may be of

importance but our present data shows

little permanent influence on American

English in this area.

A Word Geography of the Eastern

United States (Ann Arbor, 1949). This

work gives a detailed explanation of the

Eastern areas, with helpful maps.

7 George Philip Krapp, The English

Language in America (2 vols., New York,

1925), I, 35-42.

8 The

atlas records have been augmented by a correspondence questionnaire

given to 233 informants in these four states. See Alva

L. Davis, A Word Atlas of

the Great Lakes Region (unpublished

doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan,

1948). It should be noted that most of

the information thus far obtained is from

the older age group.

Dialect Distribution in the Great

Lakes Region 53

major areas, some smaller transition

areas of mixed usage occur.9

The Lead Region of northwestern

Illinois reflects its different

settlement history by the retention of

many Midland forms, and the

Marietta region retains many

Yankeeisms.10

The following words, arranged according

to their Eastern

distributions, may be used to

demonstrate the folk vocabulary dif-

ferences in the Great Lakes Region:

NORTHERN WORDS

A. GENERAL NORTH:

pail; swill, 'food for hogs'; comforter, 'tied quilt'; johnnycake;

whiffletree; boss!, 'call to cows'; angleworm; (devil's) darning

needle, 'dragonfly'; sick to his stomach

B. HUDSON VALLEY:

stoop, 'small porch'; sugar bush, 'sugar maple grove';

coal scuttle

C. THE NORTH EXCEPT THE HUDSON VALLEY:

spider, 'cast-iron frying pan'; dutch cheese, 'cottage

cheese'; fills,

'shafts of a buggy'; nan(nie)! and

co-day!, 'calls to sheep';

curtains, 'roller shades'; scaffold, 'improvised platform

for hay';

rowen, 'second crop of hay'

D. WESTERN NEW ENGLAND AND UPSTATE NEW YORK:

fried-cakes, 'baking powder doughnuts'; loppered milk, 'thick,

sour milk'; hard maple, 'sugar

maple tree'

This group of words, as a whole, is

limited to northern Ohio,

Michigan and northern Illinois, with

rare instances in the Midland

area. Those words restricted to

subareas of the East--as in B, C, D--

do not make any definite geographical

patterns within the Great

Lakes Northern area, though further

research may show that some

new subareas are to be set up.11 Most

conspicuous is the fact that

many of these words are becoming

old-fashioned, being supplanted

9 Raven I. McDavid, Jr. and Alva L.

Davis, "Northwestern Ohio: a Transition

Area," Language, XXVI

(1950), 264-273, is a preliminary study of one of these

areas.

10 Among

the Yankee terms in the Marietta area are pail, swill, dutch cheese,

boss!, and angleworm. In the Lead Region are found roasting

ears, sook!, and

fishworm.

11 Sewing needle, 'dragonfly,' for example, is current in the Upper

Peninsula

of Michigan and in the Duluth area of

Minnesota.

54

Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly

by words of wider regional and national

usage, or being forgotten

with changes in customs. Johnnycake is

a childhood memory for

many speakers, dutch cheese and fried-cakes

are now cottage

cheese and doughnuts most commonly, the whiffletree

(sometimes

whippletree) and the fills (or thills) are of little

use in a tractor

and automobile age, the old spider is

likely to be an aluminum frying

pan, and the more fashionable term window

shades is taking the

place of curtains. Rarest on

this list are scaffold, rowen, and loppered

milk (sometimes lobbered milk): the general terms

are loft or mow

-the improvised platform is now a

permanent structure in the

modern barn-second cutting, and sour

milk.

MIDLAND WORDS

A. GENERAL MIDLAND:

quarter till (eleven); blinds, 'roller shades'; skillet; dip, 'sweet

sauce for pudding'; sook!, 'call to

cows'; sheepy!; fish(ing)

worm; snake feeder, 'dragonfly'; poison vine, 'poison ivy'; belling,

'noisy celebration after a wedding'

B. NORTH MIDLAND:

spouting, 'guttering at edges of roof'; smearcase, 'cottage

cheese';

hay doodles, 'small piles of hay in the field'; sugar camp, 'sugar

maple grove'; baby buggy

C. SOUTH MIDLAND:

fire board, 'mantlepiece'; clabbered milk, 'thick, sour

milk';

trestle, 'implement to hold planks for sawing'

D. SOUTH MIDLAND AND SOUTH:

evening, 'afternoon'; light-bread, 'white bread'; clabbered

cheese,

'cottage cheese'; hay shocks, 'small

piles of hay in the field';

nicker, 'noise made by horse at feeding time'

E. MIDLAND AND SOUTH:

dog irons, 'andirons'; bucket; slop, 'food for hogs'; comfort,

'tied quilt'; pully bone, 'wishbone';

corn pone, 'corn bread';

cherry seed; butter beans, 'lima beans'; roasting ears, 'corn-on-

the-cob'; singletree; polecat;

granny woman, 'midwife'; Christ-

mas gift!, 'familiar greeting at Christmas time'

NOTE--No terms limited to the South are

common in this region.

Dialect Distribution in the Great

Lakes Region 55

The General Midland words are in common

use in the Ohio

Valley, though poison vine is

obsolescent, and blinds may be. Belling

is now common only in Ohio and

scatteringly in northern Indiana

and southern Michigan; it has been

replaced in most of the area by

shivaree, the most common term in the Middle West.12

The North Midland contains many

expressions which are

common only in Ohio; some of them have

spread into Indiana (es-

pecially the northern part of the

state), and occasionally they are

found in Illinois. Spouting is

restricted to Ohio, hay doodle is old-

fashioned in Ohio and Indiana and very

rare in Illinois, sugar camp

is most common in Ohio and Indiana, and

smearcase is common in

Ohio, Indiana, and most of Illinois (clabbered

cheese is fairly com-

mon in southern Illinois and Indiana).

These North Midland

words as a group form an irergular

wedge-like pattern: generally

current in Ohio, occasional in Indiana,

and rare in Illinois. The

Upper Ohio Valley may be the home of baby

buggy, which is now

the most usual of the words for the

perambulator in all of the Great

Lakes Region. It is, of course, a trade

term, and therefore little

affected by settlement patterns. The Dictionary

of American English

gives 1852 as the first date for baby

wagon, the earliest of the terms.

The South Midland has few terms of its

own; in vocabulary

it seems to be a transition zone

between the North Midland and the

South. Words typical of the region are

those listed, along with

sugar orchard; ridy horse, 'seesaw'; pack, 'carry'; and favor, 're-

semble.' None of these words is

especially common in this region,

but they are most frequent in the

southern portion.

Words common to large parts of the

South and the South

Midland are well represented in the

Great Lakes Midland and for

this reason these terms have been

included with the Midland group.

They seem to be slightly less common in

Ohio than in Indiana and

Illinois, further differentiating these

subareas. Light-bread, for

example, is only fairly common in Ohio,

but is the prevailing term

of southern Indiana and southern

Illinois. Nicker has probably spread

from the Virginia Piedmont; it is

common in the entire Great Lakes

Midland, even spreading into southern

Michigan.

12 See McDavid and Davis,

"'Shivaree': an Example of Cultural Diffusion,"

American Speech, XXIV (1949), 249-255.

56

Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly

The words shared by the Midland and the

South are also well

distributed in the Great Lakes Midland,

but many are becoming

old-fashioned. Dog irons become

the modern 'andirons,' corn pone,

like Northern johnnycake, has

yielded to store-bought bread, the

general term skunk occurs

alongside polecat, and few communities

have a granny woman to deliver

the babies. Christmas gift!, usually

a children's greeting, is rather rare

in the region, but information

is not sufficient to tell whether it

was ever more widely used here.

The evidence of regional

differentiation shows, in this com-

parison, surprisingly little

disturbance of the "expected" dialect

patterns, in spite of the steady

leveling influences of national ad-

vertising, ease in transportation with

its resultant mobility of popu-

lation, intermarriage, and changes in

modes of living. These in-

fluences have tended to blur some

regional differences, but the

vocabulary of everyday usage is so

extremely conservative that there

is far from complete uniformity. As yet

there is no indication that

trade and culture centers have

developed distinctive dialect areas

as has happened in the case of Boston

and some Southern cities.13

The dialect information makes, instead,

a faithful reconstruction

of the settlement patterns. The

significance of this historical com-

parison, even in its present

incompleteness, is that speech habits are

brought into the realm of historical

fact-the usage of the word

spider, for example, becomes as real as the use of the Cape

Cod

lighter or the hip-roofed barn.

13 Tonic, 'soda-pop,' is one of

the terms current in the Boston trade area. The

prestige of Boston pronunciation is well

known.