Ohio History Journal

PATRICK F. CALLAHAN

Women, Higher Education, and the

Home

Front: Women

Students at the University

of Cincinnati during World War II

As the University of Cincinnati marked

the first anniversary of the attack

on Pearl Harbor, Dean of Women Katherine

Ingle told the women students

assembled at the Women's Convocation

that "We are surrounded by danger

but there is also opportunity,

opportunity such as has come to no other gen-

eration of women, to no other race of

women...."1 Ingle foresaw the

com-

ing decade as a period when the only

"trained brains," in virtually all fields,

would be women and anticipated that the

massive shift in the gender compo-

sition of the nation's universities

caused by World War II would revolutionize

women's roles in higher education and

society.2

Ingle's prediction foreshadowed a

broader debate among historians concern-

ing the impact of the war on the status

of women in American society.

Some historians argue that the war was a

turning point in regard to economic

and social equality for women and that

the rise of second-wave feminism in

the 1960s and 1970s had its roots in

wartime changes. Others contend that it

led to few enduring economic and

attitudinal transformations regarding

women, and that wartime changes were

"for the duration" only and accom-

plished in ways that did not challenge

basic assumptions about gender roles.3

The literature is voluminous but most of

it concerns women in the work

place. Relatively little attention has

been paid to the impact of the war on

Patrick F. Callahan is Assistant Dean

for Library Technical Services at St. John's University

in Jamaica, New York. He is also a

doctoral candidate in U.S. history at the University of

Cincinnati.

1. News Record, Dec. 12, 1942.

2. The phrase "trained brains"

was coined by Virginia Gildersleeve, Dean of Barnard

College, in an article in New York

Times Magazine, May 29, 1942, p. 18, and was widely re-

peated by educators.

3. William Henry Chafe, The American

Woman: Her Changing Social, Economic, and

Political Roles, 1920-1970 (New York, 1972) and Sherna Berger Gluck, Rosie the

Riveter

Revisited: Women, the War, and Social

Change (New York, 1987) stress the

transformations

caused by the war. Leila Rupp in Mobilizing

Women for War: German and American

Propaganda, 1939-1945 (Princeton, 1978), D'Ann Campbell in Women at War

with America:

Private Lives in a Patriotic Era (Cambridge, Mass., 1984), Karen Anderson, Wartime

Women:

Sex Roles, Family Relations, and the

Status of Women During World War II (Westport,

Conn.,

1981), and Susan M. Hartmann, The

Home Front and Beyond: American Women in the 1940s

(Boston, 1982) stress the limits of

wartime changes.

40 OHIO

HISTORY

women in higher education despite the

fact that it was primarily college-edu-

cated women who led the women's rights

movement.4 Indeed, the experi-

ences of women at individual

universities, particularly coeducational ones,

have largely been ignored.5

Particularly lacking has been an attempt to elicit

the reactions of the women students

themselves.

This paper examines the wartime

experiences of women at the University

of Cincinnati, a coeducational,

municipal university.6 In an attempt to give

voice to the women students, surveys

were made in 1993 and 1994, with

questionnaires being sent to 200

randomly selected University of Cincinnati

women graduates from the classes of 1944

through 1947, of whom 90 re-

sponded.7 While there are

obvious limitations on recollections of events of

over fifty years ago, college and world

war were not ordinary experiences in

the lives of these women. The fact that

certain memories persist is indicative

of the importance of these events to

these women.8

While it is dubious to argue that any

university or its graduates are typical,

the University of Cincinnati experience,

as the rest of this paper demon-

strates, is suggestive of the extent and

permanence of the changes wrought by

the war regarding the collegiate

experiences of women students. It suggests

that the war did dramatically alter the

gender composition of the campus and,

as a result, significantly affected

campus social life. The war temporarily

produced greater opportunities for women

students in terms of available fields

of study, career choices, and student

leadership positions. However, changes

4. Susan Hartmann devotes a chapter in The

Home Front and Beyond to women in higher

education. Also see I. L. Kandel, The

Impact of the War Upon American Education (Chapel

Hill, 1948), and Mabel Newcomer, A

Century of Higher Education for American Women (New

York, 1959). The best treatments of

women in higher education, Barbara Miller Solomon, In

the Company of Educated Women: A

History of Women and Higher Education in America

(New Haven, 1985) and Helen Lefkowitz

Horowitz, Campus Life: Undergraduate Cultures

from the End of the Eighteenth

Century to the Present (New York,

1987), pay relatively little

attention to the war years.

5. See, for example, Reginald C.

McGrane, The University of Cincinnati: A Success Story in

Higher Education (New York, 1963) which devotes only 21 pages to the war

years with only

an occasional reference to women. The

best published account of women and the war at the

University of Cincinnati is an

undergraduate honors paper by Cynthia Hajost, "U.C. Women

During WW II," Forum: A Women's

Studies Quarterly, 8 (Spring, 1982).

6. It should be noted that this is

primarily the story of white women. Blacks and Asians com-

prised fewer than 2 percent of the

student population, male and female, based on an examina-

tion of the Cincinnatian, the

school yearbook, for the years 1941 through 1945.

7. The 200 women were selected from the

1003 women of the classes of 1944-1947 for

whom the University's Alumni Association

has records. Four surveys were returned as unde-

liverable.

8. Survey results were used, not to

recreate campus events, but to gauge personal reactions

to those events and to determine wartime

impacts on the lives of these women. Factual data

was obtained from university records

contained in the University of Cincinnati Archives.

Three frequently cited published sources

are the News Record, the student newspaper of the

University of Cincinnati published in

day and evening editions, the Cincinnatian, the student

yearbook, and, Profile, the

student literary magazine. All unattributed quotations are from the

surveys.

Women, Higher Education, and the Home

Front 41

in women's academic programs were

minimal, and the academic and career

choices of women students changed only

modestly. Nor did the war signifi-

cantly affect the attitudes of the

university community toward women or the

beliefs of women students themselves

regarding the role of women in

academia and in American society as a

whole.

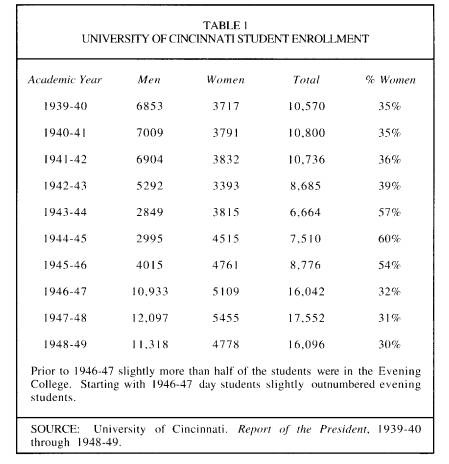

The University of Cincinnati, like other

coeducational universities, changed

during World War II from a predominantly

male to a predominantly female

student body.9 In 1940, 35

percent of its 10,800 students were women. With

the departure of almost 60 percent of

its male students into the military or

war work, the University's total

enrollment declined precipitously, to a low

of 6,664 in 1943-44. However, the number

of women increased until by

1944-45 women comprised 60 percent of

the student population (See Table

1).10 Women made up 70 percent of the

class entering that academic year.

This drastically changed the character

of the university, causing one graduate

to recall that "it was like going

to a girls school with a boys' school (the

ASTP [Army Specialized Training

Program]) close by."

Educators and the federal government

quickly recognized that the reduction

in the number of male students would

produce shortages in professions such

as medicine, engineering, and business,

and that women would be needed to

make up the shortfall. As Margaret S.

Morriss, Dean of Pembroke College

and Chairman of the Committee on College

Women Students and the War,

American Council on Education, said:

"The colleges at present are responsi-

ble for providing all the women

scientists they can; mathematics, physics,

and chemistry should be studied to the

greatest possible extent."1 1

The University of Cincinnati responded

in much the same way as universi-

ties across the country. First, it

instituted an accelerated curriculum which al-

lowed students to complete their degrees

in less than the usual amount of

time by taking classes year round, thus

enabling them to enter war work more

quickly. However, this initially

affected few women because they were under-

9. The University's enrollment patterns

mirrored national trends which showed a 45 percent

decline in university and liberal arts

college enrollment from 1,167,304 in 1939-40 to 638,355

in 1944-45. In 1939-40, 36 percent of

the students were women (423,906). The percentage

rose to 67 percent in 1944-45 (429,178)

as the total number of women students actually in-

creased by 1.4 percent over prewar

levels. The figures are those of the U.S. Office of

Education compiled for U.S. 79th

Congress, 1st sess., House Report 214 "Effect of Certain

War Activities upon Colleges and

Universities," Report from the Committee on Education,

House of Representatives pursuant to

H. Res. 63 (Washington, D.C., 1945).

10. The increase in the absolute number

of women was confined to undergraduates, as the

number of female graduate students

declined during the war, although less dramatically than

male students. Women were never in a

majority, peaking in 1944-45 at 48 percent. University

of Cincinnati, Report of the

President, 1939-40/1940-41, 182-83, 188-89; 1943-44/1944-45,

154-55, 159-60.

11. College Women and the War:

Proceedings of the Conference held at Northwestern

University, November 13-14, 1942 in Northwestern University Information, Vol. 11,

no. 6 (Nov.

9, 1942), 19.

|

42 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

represented in those fields targeted for acceleration, such as medicine, engi- neering, law, and business.12 Nor did women often select this option when it was offered in fields with larger concentrations of women. For example, the School of Household Administration dropped its plans for an accelerated cur- riculum due to lack of student interest.13 Cincinnati was not unique in this regard; the American Council on Education complained that "women students did not avail themselves of such opportunities [acceleration] to anything like the extent to which the men participated."14 The notable exception was the

12. In the survey, only two non-nursing students mentioned acceleration as a factor in their own education. 13. Report of the President, 1941-42/1942-43, 5, 48, 57, 64. 14. American Council on Education, College Women and the War (West Lafayette. Ind., |

Women, Higher Education, and the Home

Front 43

College of Nursing and Health which

condensed its usual four-year program

to three years. However, since

acceleration did not start until fall 1943 and

was discontinued in 1946, only those

students entering school in 1943 spent

their entire program in the accelerated format.15 Second, the University

formed the War Service Training

Institute which offered defense and war

courses especially designed for women.

These courses were not directed at

traditional students but were meant to

expand the pool of women taking

University courses. The courses were

supposed to appeal to high school stu-

dents of "superior academic

standing," workers in non-war industry jobs that

do "not call upon the full use of

your capacities," and housewives "willing to

offer your services to this

emergency."16 The

programs, for the most part,

coincided with the wartime needs

identified by the federal government and the

American Council on Education and were

similar to those offered at other

universities. 17

Finally, the University, like many

others, permitted women to enter fields

of study from which they were previously

barred. The most significant of

these was engineering in which the first

women were admitted during the war,

the rationale being that the shortage of

men and the critical need for engineers

in war industries necessitated the

training of women engineers. It was also in

the University's self-interest since the

College of Engineering and Commerce

had experienced a 60 percent decline in

students. Women students helped off-

set the loss of male students and,

additionally, kept the faculty gainfully em-

ployed. By 1944-45, 266 (40 percent) of

the College's 671 students were

women. This compared to 82 women (5

percent) out of 1707 students in

1941-42.18

These wartime academic innovations

affected relatively few degree-seeking

women. Indeed, it was the limited impact

of the war on the academic careers

of most women students that was most

striking. The war did result in the

loss of faculty because of military or

governmental leaves of absence which,

at times, resulted in fewer classes

being offered.19 However, this seems to

1943), 7. This was a reprint of the

Council's Higher Education and National Defense Bulletin,

no. 35, 42,45,47, 48.

15. Survey; Report of the President, 1943-44/1944-45,

69; 1945-46/1946-47, 75.

16. "Your Country Needs Trained

Woman Power to Speed Her Victory Program," Jan. 5,

1943, draft of a War Service Training

Institute brochure in Box 13 of Dean of Arts and

Sciences files, University of Cincinnati

Archives.

17. Ibid., 9; Northwestern University, College

Women and the War, 23-29.

18. The College of Engineering and

Commerce did admit women to most of its business pro-

grams prior to the war. From the

available statistics it is not possible to distinguish engineering

students from business students during

the war years, although it is clear that the vast majority

of women were business majors. Report

of the President, 1941-42/1942-43 and 1943-44/1944-

45.

19. Report of the President, 1941-42/1942-43,

45, and Survey. McGrane estimates that 200

faculty members, mostly men, were

granted war leaves, but it does not appear that the gender

composition of the faculty was

significantly altered.

44 OHIO

HISTORY

have been a minor inconvenience that was

partially offset by the advantage of

having more senior professors teaching

undergraduate courses.20 The

core

curriculum in most fields changed

little.21

More importantly, most women students

did not change their academic

plans. Despite a national propaganda

campaign to convince women students

to enter the sciences and mathematics,

there was little movement at

Cincinnati into these male-dominated

fields. The number of women majoring

in the so-called women's subjects-

nursing, education, home economics, and

the applied arts- declined only from 68

percent in 1940-41 to 57 percent in

1944-45, and this was almost entirely as

a result of the rising number of

business administration majors.22

Many contemporaries perceived a greater

amount of change than actually occurred.

For example, the Dean of the

College of Medicine boasted that the

College admitted in 1944-45 "by far the

largest number of women in its

history" even though there were still only 23

women out of a total of 328 students, an

increase of only eight women over

1940.23

That so few University of Cincinnati

women students availed themselves of

the new career opportunities presented

by the war was because many of them

entered college with a firm idea of the

course of study and the occupation they

wished to pursue. These were usually

those careers which American society

deemed appropriate for women, such as

nursing and teaching. The war also

produced a great demand in these

predominantly female fields, thus making it

unnecessary for women to change

long-held career plans. For example, the

National Education Association estimated

that by September 1944 there was a

shortage of approximately 70,000

teachers nationally.24 The shortage was re-

flected at Cincinnati by an increase in

requests for teachers received by the

Teachers College Bureau of Placement

from 159 in 1939-40 to 689 in 1941-

42.25

Also, by 1944 the War Manpower

Commission estimated that the national

demand for civilian and military nurses

exceeded supply by 100,000.

Congress, in an attempt to increase the

supply, passed the Bolton Act in May

1943 which, among other things, created

the United States Student Nurses

20. Survey.

21. A comparison of the University's Annual

Catalogue of all Colleges for the years 1940-41

through 1946-47 shows little change in

course offerings or program requirements. In addition

those women surveyed reported little

change in the content of their own programs or individual

courses.

22. Report of the President, 1939-40/1940-41,

188-89; 1943-44/1944-45, 150-60. The re-

maining women majors in 1944-45 were

distributed as follows: Liberal Arts, 26 percent;

Engineering and Commerce, 13 percent;

Graduate, 3 percent; Medicine, I percent; and Law,

less than 1 percent.

23. Report of the President, 1941-42/1942-43,

172-73 and 1943-44/1944-45, 159-60.

24. New York Times, July 9, 1944.

25. "Annual Report of the Bureau of

Placement," 1942-43 in Box 1, Faculty Minutes folder,

College of Education files, University

of Cincinnati Archives.

Women, Higher Education, and the Home

Front 45

Corps, an organization which provided

direct financial aid to students entering

nursing.26 Between 1943 and

1948, the Corps financed the educations of ap-

proximately 125,000 women students

nationwide. At the University of

Cincinnati, 70 of the 76 women entering

the nursing program in fall 1944

belonged to the Corps, and 141 of the

197 nursing students in 1945-46 were

Corps members.27 Nursing was one of the few programs

in which women

received financial assistance as a

result of the war. The fact that this actually

attracted students who had not

previously considered a career in nursing indi-

cates that similar incentives might have

attracted more women to careers in

the sciences.

Another reason few women seized these

wartime opportunities was the

mixed messages that women students

received concerning their wartime role.

On the one hand, government agencies

such as the War Manpower

Commission reminded them that "All

women college students are under obli-

gation to participate directly either in

very necessary community service, in

war production, or in service with the

armed forces."28 But, despite admoni-

tions that universities counsel their

students to prepare for fields useful for

war production such as the sciences and

mathematics, administrators extolled

the value of a traditional liberal arts

education. University administrators at

Cincinnati and elsewhere urged women

students to stay in school and plan for

the long-term. University President

Raymond Walters told women students:

"As for you young women, I strongly

urge you to ponder your patriotic obli-

gation. You can doubtless obtain a

well-paid war job, but it is likely to be a

blind alley. ... For your future and

that of the nation, your duty lies, I

think, in preparation for larger

usefulness."29 What

little career counseling

the University provided often steered

women to traditional career paths. One

alumna recalled that the Dean of Women

"strongly advised me against major-

ing in math unless I wished to teach

it" because there were no scholarships

available to women mathematics majors.30

26. "An Act to Provide for the

Training of Nurses for the Armed Forces, Governmental,

Civilian, Hospitals, Health Agencies and

War Industries .. ." Pub. Law 74, US Statutes at

Large, Vol. 57. pt. 1 (1943), 153-55. The act was named for its principal sponsor,

Representative Frances Bolton of Ohio;

it is described, along with wartime nursing in general,

in Doris Weatherford, American Women

and World War II (New

York, 1990), 16-25, and

Campbell, Women at War with America, 49-61.

27. University of Cincinnati School of

Nursing and Health, "Schools of Nursing Annual

Report for Year Ending June 1,

1946," to the State of Ohio, State Medical Board, in Box 8,

Ohio State Nurses' Board folder, College

of Nursing and Health files, University of Cincinnati

Archives.

28. Dr. Edward C. Elliott of the War

Manpower Commission in Higher Education and

National Defense, no 35 (Oct. 17, 1942), 2.

29. "The President's Message to

Prospective Freshmen," April 12, 1945, Box 7, Raymond

Walters Papers, University of Cincinnati

Archives.

30. She ignored this advice and received

her degree in mathematics although she did end up

in teaching, ironically getting her

first job at the University of Cincinnati due to the loss of

faculty during the war.

46 OHIO

HISTORY

In many respects the University

reinforced the ideology of domesticity.

College women were posited as cultural

guardians who ensured a moral and

civilized society. President Walters

reminded women students throughout the

war that "More than ever the burden

falls upon young American women to

carry the torch of liberal and

professional knowledge, so that the noble tradi-

tions of science, culture, and religion

are maintained in this land. The great

lights must not go out."31 It

was a message reinforced by a curriculum that

assumed the temporary nature of wartime

changes. As Eleanor Maclay, head

of the Department of Nutrition, said:

"Why do we still bake cakes? This war

won't last forever, and these women

should know the principles of food

preparation, so we continue to make

cakes."32

Even the courses offered through the War

Service Training Institute tended

to be, though not exclusively, in those

areas in which women traditionally

were considered to have an aptitude,

such as health care, social work, food

services, languages, and secretarial

work.33 Perhaps the most significant rea-

son for the lack of movement into

male-dominated fields was that few women

believed that the opportunities in war

industries or "male" professions were

anything but "for the duration

only." They were, as it turned out, correct

since male veterans reclaimed jobs in

the professions and factories after the

war. But, there was also ample evidence

during the war to support this belief

since there were distinct limits to the

wartime opportunities available to

women. In Cincinnati's Cooperative

System of Technological Education, or

co-op system, for example, placement

officials continued to guide men into

production and management trainee

positions in manufacturing plants while

women students were directed to clerical

and general office positions.34 In

general, women students at Cincinnati

did not appear to believe that the war

would cause a major change in their

long-term career prospects or in job-re-

lated gender stereotyping. There were

virtually no expressions at the time or

in the survey that indicated that women

students believed that the war would

produce long-term change in these areas. Very few survey respondents

thought the war affected their beliefs

as to what careers were suitable for or

available to women.

The war had a greater impact on campus

life in general than it did on aca-

demics, but even here the effect on

women was mixed. This is not surprising

given the diverse nature of the student

body. Many women at Cincinnati

31. "The President's Message to

Prospective Freshmen," April 12, 1945.

32. News Record, March 27, 1943.

33. Full descriptions of each program,

including the required courses, are contained in Box

13, Programs of Study folder, Dean of

Arts and Sciences files, University of Cincinnati

Archives.

34. The co-op program at Cincinnati was

designed to give students practical experience as

interns in businesses. It was well

regarded nationally. There were separate curricula for men

and women students. University of

Cincinnati, Annual Catalogue, 1940-41, 30-33; 1946-47, 36-

40.

Women, Higher Education, and the Home

Front 47

resided with their parents and commuted

to campus, which limited their in-

volvement in campus social life, while

nursing students lived at the

University hospital located almost a

mile from campus; this and the nature

of their nursing schedules precluded

participation in campus social activities,

a situation that was exacerbated during

the war when most worked extra hours

in the wards. A 1944 nursing graduate

remarked on the obstacles to social

involvement: "As nursing students

we had a 48 hour week (for example if we

had 24 hours of class we had 24 hours of

ward work), by adding 12 hours of

extra duty our energy level was not

abundant. We, too, had to study!"

For many other students, prewar campus

social life had revolved around

football games, fraternity parties, and

formal dances, activities which were

curtailed or eliminated during the war.

Football was suspended for the 1944

and 1945 seasons, and eight of the

University's sixteen fraternities went on

inactive status during the war because

of the shortage of men. On the other

hand, sororities flourished with

record-breaking pledge classes.35

The most disruptive change was in the

area of dating where the lack of men

students was keenly felt. As historian

Beth L. Bailey has observed, the war

undermined a system of courtship based

on demonstrating popularity through

the quantity of dates and paved the way

for a new system which emphasized

going steady.36 The

Cincinnati experience lends credence to this interpreta-

tion; there was a greater emphasis on

steady relationships. A campus poll

showed that 85 percent of women students

were willing to get engaged to a

man who was about to enter military

service, and other anecdotal evidence in-

dicates that there was an increase in

the number of engagements. There was

not, however, a "rush to the

altar." The same campus poll indicated that only

31 percent of the women were willing to

marry a man before he entered the

military for fear that the war might

cause a personality change that would re-

sult in a failed marriage.37 Also,

statistics from the College of Nursing and

Health indicate that women withdrew from

school to get married during the

war at about the same rate as they had

before the war, one to three per year.38

There was an attempt to maintain the old

social system. The University of

Cincinnati did not establish a dating

bureau as was done at many other mid-

western universities, such as Michigan,

Minnesota, Northwestern, and Ohio

State.39 However, almost all

the survey respondents commented on the ab-

sence of men and the consequent impact

on dating possibilities. A 1945

graduate noted that "there were

4F's (& some were pretty cute) but we had

35. News Record, Jan. 12, 1944: Cincinnatian,

1944.

36. Bailey, Beth L. From Front Porch

to Back Seat: Courtship in Twentieth Century America

(Baltimore, 1988)

37. News Record, Dec. 5, 1942.

38. "Schools of Nursing Annual

Report for Year ending .... 1941-1947, Box 8, College of

Nursing and Health files, University of

Cincinnati Archives.

39. Bailey, From Front Porch to Back

Seat; Minnesota Daily, May 18, 1943.

48 OHIO HISTORY

very few dates." A large number of

survey respondents also noted, with re-

gret, the curtailment of dances, the

principal forum for collegiate social life.

However, even though some events such as

the Junior Prom in 1942 were

canceled, many of the campus social

functions merely took on a military mo-

tif through USO sponsorship or the

involvement of Army Specialized

Training Program soldiers, such as the

1942 Victory Dance at which a "V"

Queen was selected.40 Numerous dances and socials were held to

allow

women students to get acquainted with

military personnel, some of which the

USO sponsored at area military bases,

such as Camp Atterbury in Indiana and

Fort Knox in Kentucky. These events did

not, however, necessarily compen-

sate for reduced dating possibilities.

In fact, student USO hostesses were pro-

hibited from dating the servicemen they

entertained.41 On the other hand, the

presence of service men on campus

provided social contacts that otherwise

would not have occurred, and several

survey respondents indicated that they

dated, and some eventually married, ASTP

soldiers.

While most of the alumnae surveyed noted

the negative impact of the war

on campus social life, few expressed

regrets. As one woman stated:

I suppose we missed some of the hoop-la

of college life. I never felt the lack of

this. We learned to make life pleasant

for ourselves by ourselves. Most of us had

boy friends in dangerous places. My best

friend's fiance was killed in the Battle of

the Bulge. Some of us had to grow up

pretty fast.

Thus it is clear that having loved ones

at war conditioned how some women

experienced college life. A 1945

graduate observed that "it was a time of

great emotional strain ... It was a time

of worry and concern for the men in

service. It was a time of letter writing

and waiting for the postman." A 1947

graduate whose high school boy friend

was killed in Germany in January

1945 recalled that "this was very

devastating to me and as a result I was not

all that concerned with dating and

social activities." She also expressed the

sentiment that "I think everyone

had someone they loved in service and we

lived in fear, prayed a lot, wrote many

V-mail letters, and tried to be cheerful

and supportive of each other. There was

a closeness and a team feeling of

pulling together."

This statement reflects both the greater

seriousness of women students dur-

ing the war, something noted by many

respondents, and a greater sense of

camaraderie among women. The war

"drew women closer together" both

through the common bond of having a

loved one overseas and from the mere

fact of spending more time together.

Playing cards and going to the movies

together became substitutes for dating.

40. News Record, Jan. 17, 1942,

Feb. 25, 1942.

41. News Record, Evening College

ed., May 8, 1943, May 15, 1943, and survey responses.

|

Women, Higher Education, and the Home Front 49 |

|

Women also engaged in war-related volunteer activities, many of which, such as sorority war-bond drives, involved women exclusively. Drawing on a long tradition of female voluntarism, they served as nurses aides, USO hostesses, worked for the Red Cross, and sold war bonds. Many of these vol- untary activities were extensions of women's domestic roles. Women stu- dents knitted sweaters, socks, and scarves for the Red Cross refugee relief pro- gram and Bundles for Britain, and students in the College of Home Economics volunteered to go to area grocery stores to explain the rationing system.42 The Women's Unit of Quadres, an African-American student orga- nization, worked in the black community under the auspices of the Community Chest; they helped in nursery schools, organized youth clubs at the Nash Community Center, and conducted studies of civic and industrial ac- tivities in Cincinnati as they related to African-Americans. They argued that they were aiding the war effort by helping to solve domestic problems, such as juvenile delinquency, thus allowing the nation to devote more attention to defense.43 The apparent major exception to this domestic emphasis was the Cincinnati Auxiliary Defense Effort and Training Corps (CADETS) whose members took defense classes and engaged in weekly military drill, complete with mili- tary-style uniforms. This civil defense component waned after its first year of operation, 1942, however, and the organization thereafter performed largely the same type of community service as other campus organizations. Despite the seemingly nontraditional aspects of women in military uniform, one of

42. Cincinnati Alumnus, 14 (fall, 1940); 15 (Spring, 1943); Survey. 43. Profile, 5 (Dec., 1942), 12. |

50 OHIO HISTORY

the avowed purposes of the CADETS was to

"acquaint women with the top-

ics which men will discuss the rest of

our lives, and help them understand the

processes of war," which indicates

a greater concern for postwar readjustment

than for defense per se.44 The

purpose of the military drill was vague. A

former member described the CADETS as

"a uniformed phys. ed. class," and

another remarked that "I don't remember

what we actually accomplished."45

While these voluntary efforts seldom

took women beyond their traditional

roles, the war provided them with

opportunities to move into leadership posi-

tions in student organizations which men

previously monopolized. In fact,

the whole structure of student

government was gender-based. Specific posi-

tions were reserved for men, others for

women, and there were separate Men's

and Women's Senates to govern their

respective activities. It was a gover-

nance structure that mirrored that of

the University itself in which the only

female senior administrators were those

dealing exclusively with women stu-

dents: the Dean of Women and the Deans

of the School of Household

Administration and the School of Nursing

and Health.

From 1943 to 1946, the preponderance of

female students on campus thrust

women into many student leadership

positions. For example, starting in 1943

with the appointment of Mary Linn

DeBeck, the News Record, the student

newspaper, had four consecutive women

editors, the first four in the paper's

history. The staff of the paper also

became predominantly female, a change

which produced a change in content,

particularly of the editorials. Prior to

1943, the editorial page seldom dealt

with specifically women's issues. This

changed under the women editors as

numerous editorials dealt with women's

topics, many of which were perceived as

controversial. In a May 15, 1943,

editorial, DeBeck challenged the

University administration to act to protect

women from "the growing incidents

of attempted molestations of women on

and around the campus." In a

January 12, 1944, editorial, she criticized the

administration for allowing too many

ASTP soldiers on campus to the detri-

ment of civilian students, women in most

cases. This created something of a

furor on and off campus as DeBeck was

denounced as unpatriotic by the city's

daily newspapers. Later, Louise Dreifus,

the 1945-46 editor, attacked the fra-

ternity system as being educationally

"worthless," representative of the "herd

instinct," and placing excessive

value on clothes and money.46 This distinc-

tively female quality of the paper was

later noted by the new male editors in

1947 who claimed that the "four

year petticoat dynasty" had "stepped on more

toes and raised more eyebrows than ever

before."47

44. News Record, Feb. 20, 1943.

45. Survey; After initial enthusiasm the

membership in the Corps dropped to about 150 in

1944 from a peak of 500 in 1942. News

Record, Sept. 26, 1942; Oct. 17, 1942; Cicinnatian,

1944, 152.

46. News Record, Feb. 14, 1946.

47. News Record, June 7, 1947.

Women, Higher Education, and the Home

Front 51

Men continued to monopolize the class

and student council presidencies,

but a woman, Rosemary Kauffman, was

defeated only after a runoff election

for senior class president in 1943. Not

only was it unprecedented for a

woman to come this close to winning, it

was unusual for a woman even to

run for the office.48 (It

should be noted that voter participation in these elec-

tions was, as it is today, very low.)

However, the fact that men continued to

win these elections despite the

preponderance of women voters indicates how

entrenched traditional gender

distinctions were.

The election results provide evidence of

the limits of change. The allot-

ment of offices on the basis of gender

not only persisted during the war, but

women apparently never even questioned

the arrangement. They may have

been partially motivated by a desire to

make no waves in order to maintain

control over their own affairs, which

organizations like the Women's Senate

provided them. Thus, while many of the

women surveyed acknowledged the

war's role in allowing them to hold

offices they otherwise might not have

held, many echoed the sentiments of a

1944 graduate who "did not have the

vision or the desire to fill those

commonly reserved for men."

The University community in general

reacted ambivalently to the new

prominence of women on campus during the

war. The University administra-

tion was very positive, at least in the

short-term, a not surprising reaction

since the University depended on the

revenue derived from women students to

keep it afloat. Efforts to recruit women

students intensified during the war.

The University, for the first time,

formed a Committee on Admission in

April 1944 whose function was to travel

throughout Ohio, Indiana, and

Kentucky to attract prospective

students, mostly women, to the University.

The administration credited the

Committee with attracting "the largest group

of women students in the University's history

and also the largest number of

non-resident women students."49

Plans for a new women's dormitory were

initiated in an attempt to attract more

out-of-state women, and the Evening

College added courses designed to appeal

to women. Initially these were

courses whose goal was to improve

women's chances of employment or

promotion in the war economy, but during

the last two years of the war, they

tended to deal with cultural or domestic

topics.50

The war experience did cause some

administrators and faculty to moderate

their views on gender difference.

President Raymond Walters, after noting

that women had performed well in the

areas of science and medicine, con-

cluded that: "The difference based

on sex is less than is commonly thought.

48. News Record, Nov. 10. 1943.

49. Report of the President, 1943-44/1944-45,

30. Nonresident status refers to someone who

did not reside in Hamilton County, Ohio.

50. For example. Frank Neuffer, Dean of

the Evening College reported a 57 percent in-

crease in applied arts enrollment in

fall 1944; Cincinnati Post, Sept. 27, 1944, Oct. 4, 1944, Jan.

9, 1945.

52 OHIO

HISTORY

Our women students of high intellectual

calibre are not greatly different in

their mental processes than men

students."51 After observing women engi-

neering students, Bradley Jones, Head of

the Department of Aeronautical

Engineering, conceded that "women

are not devoid of brains."52

Women's success in new subject areas,

however, was often explained in

stereotypical terms. For example,

Ernest Pickering, Professor

of

Architecture, after observing the women

in his Evening College drafting and

architectural drawing classes, concluded

that "women show a special aptness

for these two subjects because of their

natural tendency to detail and exact-

ness."53 Moreover, women

who took traditionally "male" classes encountered

persistent prejudice.54 Two premed

students felt that the few women in their

classes were singled out for scrutiny by

the professors, while a nursing stu-

dent recalled feeling sorry for the

female physicians in the hospital who "were

often treated by their male peers as a

sort of laughing stock & were frequently

the victims of rather cruel practical

jokes & tricks." Another alumna remem-

bered being "treated terribly-like

a leper" in a premed physics course taught

by "the original sexist."

Typical of the condescending attitude toward women

that persisted among many faculty and

administrators was that of George

Barbour, Dean of the College of Liberal

Arts. While recognizing that

"evidently sex-differences are also

rationed for the duration," Barbour could not

take women seriously as students,

instead seeing them as yearning for the re-

turn of men to campus. "The girls

are all praying for this. Otherwise, why go

to college?"55

Nor does the administration's

paternalistic attitude towards women students

appear to have been altered by the war,

as exemplified by President Walters

who justified the new dormitory for

women on the grounds that "parents quite

naturally refuse to have their daughters

live in private dwellings in a large

city."56 Throughout the

war, the University strictly regulated the interaction

of women students and military personnel

at social functions, insisting that

51. Raymond Walters, "Chi Omega Address." April 8, 1945, in Box

7 of Raymond Walters

Papers, University of Cincinnati

Archives.

52. News Record, Nov. 16, 1944.

53. Cincinnati Post, Jan. 8,

1945.

54. It should be noted that experiences

and perceptions varied in this regard. Some survey

respondents reported that they were well

received by both male faculty and students.

55. Letter, Dec. 20, 1942. Box 13, War

Folder, Dean of Arts and Sciences files, University

of Cincinnati Archives.

56. A bond issue to construct the

women's dormitory, among other projects, was approved

by the voters on Nov. 7, 1944, but the

dormitory was never built. Instead the money was di-

verted to build housing for servicemen

returning to college via the GI Bill. The housing short-

ages after 1945 led to some relaxation

of the restrictions on women in off-campus housing. In

fact, women graduate students and

ex-service women were asked to find rooms in private

homes so as to make room for male

veterans and their families. Report of the President, 1943-

44/1944-45, 20, 25; "Cabinet

Minutes," March 14, 1946, Box 16, Raymond Walters Papers.

University of Cincinnati Archives, News

Record, Nov. 2. 1944.

Women, Higher Education, and the Home

Front 53

the students be properly chaperoned.

Indeed women students had to supply a

faculty reference and the name of their

priest, rabbi, or minister when apply-

ing to be a USO hostess.57

Ironically, the University's most

paternalistic and intrusive administrators

were the females who directed the

College of Nursing and Health. Their poli-

cies actually grew more restrictive

during the war. Nursing students, most of

whom lived in a dormitory attached to

the hospital, had strict visitation rules,

were required to have lights out by

11:30 p.m., and could not join sororities

or have numerous social activities

unless approved by the College's

Executive Committee. Nor could nursing

students marry without the permis-

sion of the College administrators, a

rule which led at least one student to

marry secretly, a transgression which

when discovered resulted in her dis-

missal. All of these regulations

persisted into the postwar period although

there is some evidence that the wartime

experiences caused some women to

chafe at the restrictions.58

In general, male students treated the

intrusion of women into the male

sphere as an amusing, temporary

phenomenon. Some anticipated "pink cur-

tains on bridges" now that women

had entered engineering.59 A male reporter

for the News Record wrote about

the student union: "There was a time when

a "femme" who dared to invade

the male sanctuary of the pool table area was

looked upon in much the same amazed and

unwanted manner a roach would be

when suddenly discovered in a sandwich

.... Maybe the phrase 'man's

world' is another casualty of war."60

In general, such changes, because they

were temporary, were not seen as threats

to male prerogatives. Thus women

training to be engineers or playing pool

were notable precisely because they

were odd, not because they were

establishing precedents for future behavior.

The end of the war in 1945 produced

another radical shift in student demo-

graphics at Cincinnati and nationally.

Fueled by postwar prosperity and the

GI Bill, enrollment doubled over wartime

levels, rising to 17,552 in the

1947-48 academic year; this was

approximately a 70 percent increase over the

enrollment in the years immediately

preceding the war. While the number of

women students grew steadily throughout

the period, women as a percentage

of the student population fell to less

than a third, a figure lower than prewar

levels. This was because the number of

men, many of them veterans, sky-

rocketed from 2995 in 1944-45 to 12,097

in 1947-48.61

57. News Record, May 8, 1943, May

15, 1943.

58. Ninety-nine of the 109 members of

the class of 1946 signed a petition requesting greater

freedom to leave the dormitory without

permission. "Executive Committee Minutes," and

"Annual Report to the National

League of Nursing Education," 1946, in College of Nursing

and Health files, University of

Cincinnati Archives; Survey.

59. News Record, Nov. 16, 1944.

60. News Record, April 12, 1945.

61. See Table 1.

54 OHIO

HISTORY

University administrators embraced the

mission of educating veterans with

a single-mindedness that surpassed the

University's wartime efforts. In the

process, the needs of women students

increasingly took a backseat to those of

veterans.

Plans for a new women's dormitory were

quickly dropped in favor of mar-

ried student housing. While most women

students applauded the return to

"normal" campus life, some

were concerned with the possible reversal of fa-

vorable wartime changes. In 1946,

Barbara Apking and Alice Decker, editors

of the Evening College edition of the News

Record, responded to the sugges-

tion that women defer their educations

in order to accommodate the veterans:

It's the same old story of in time of

war women are found to be very handy to keep

industry going and the guns firing, and

in saving educational institutions from

walking the "last half mile."

But as soon as the emergency is past, they are ex-

pected to fold their hand and retire to

their behind-the-scenes rockers and pots and

pans.... It is our humble opinion that

there should be education and equal oppor-

tunity for all. Women did their bit

during the war. Why should they be discrimi-

nated against because they wear skirts

and carried a torch instead of a gun!62

Such concern was justified because many

wartime academic innovations

were abandoned within two years of the

war's end. The government and edu-

cators no longer urged women to enter

the sciences or other "male" profes-

sions, and even the modest wartime

changes in women's academic behavior

largely disappeared. By the 1947-48

academic year, 61 percent of the full-

time women students majored in nursing,

teaching, home economics, and ap-

plied arts, only 7 percent fewer than

before the war.63 Significantly, women

accounted for only 16 of the 2155

engineering students, 25 of the 340 medical

students, and 20 of the 439 law students

while the field showing the largest

increase among women was home economics.64 On the other hand, some

important wartime precedents did

persist. While there were few women engi-

neering students, the program did not

revert to its previously all-male status.

In the social arena, the large influx of

men did not cause a reversion to pre-

war dating patterns, perhaps because

many of the returning veterans were al-

ready married and thus more serious

about academic pursuits.65 The

accep-

tance of married students, something

frowned upon in prewar days, fit in with

the greater emphasis on steady

relationships.

62. News Record, Evening College

ed., May 16, 1946.

63. This percentage would have come

close to matching the prewar figure if not for a pre-

cipitous decline in the number of

nursing students. The remaining women were distributed as

follows: Liberal Arts, 26 percent;

Business Administration, 7 percent; Graduate School, 3.5

percent; Medicine, 1 percent; Law, 1

percent; Engineering, .5 percent. Report of the President,

1947-48/1948-49.

64. Ibid.

65. Many of the survey respondents

remarked, with approval, on the greater seriousness and

maturity of the veterans.

Women, Higher Education, and the Home

Front 55

Men quickly reasserted their dominance

of campus leadership positions.

The campus publications taken over by

women during the war once again had

men in the leading editorial positions

and women in subordinate staff posi-

tions. Women students generally accepted

this return to the prewar order; a

1945 graduate's comment is typical:

"Men were still given the higher offices

.. we felt nothing wrong with this. Our

roles were subordinate & we didn't

quarrel with that."

However, women students were not willing

to forfeit all wartime gains.

For example, the shortage of men during

the war had enabled women to join

the university band for the first time.66

In fall 1946, after some male band

members lobbied to have the band

returned to all-male status, women mem-

bers rebuffed the attempt; band director

Merrill B. Van Pelt gave the women

lukewarm endorsement, saying that

"they've been very faithful, and their per-

formance has been adequate."67

Apparently the war did not produce many

lasting changes in women's roles

in the University community, nor did it

change the attitudes of the women

students concerning their role in

American society. Obviously their reactions

varied considerably, with much depending

on individual college experiences,

and attitude formation is difficult to

gauge after a lapse of fifty years. But

based on the responses to the survey,

wartime experience produced little sig-

nificant change. Approximately 85

percent of the respondents indicated that

the war did not alter their attitudes

toward career, marriage, or family. For the

most part, they had always anticipated

getting married and having a family,

and the war did little to change this

feeling. Most did in fact get married and

have children during or after the war,

thus fulfilling the role mapped out for

them by peacetime society.

There was less unanimity about how a career

fit into this plan. One end of

the spectrum was represented by the

alumna who replied that "most women of

my age group felt that marriage was a

goal in itself.. ." and that women

wanted a family, not a career. More

common, however, was the sentiment of

an education major who said "I

still wanted marriage, a family, then teach-

ing-in that order." These

priorities were reflected in the most typical post-

graduation behavioral pattern, namely

that of pursuing a career until marriage

and then quitting either after marriage

or after the birth of the first child. As

one graduate remarked, "I still

wanted to become a mother & only worked un-

til the wedding. No one in my circle

worked after marriage." Others, how-

ever, returned to work after their

children were grown. While most were

pleased with the path they chose, some,

in retrospect, were not totally satis-

fied with how their lives unfolded. As a

1946 dietetics major stated: "All of

my college friends stayed home with the

children. Yet as I look back, I regret

66. News Record, Oct. 20, 1943.

67. Cincinnati Post, Nov. 18,

1946; Cincinnatian, 1946.

56 OHIO HISTORY

that I did not continue my work when I

married. It was expected that women

did not continue work."

Not surprisingly, a couple of

respondents went to college never intending

to marry, and nothing happened to change

their minds. Others retained the

same desire for marriage and children,

but the uncertainty of the war era drove

home the importance of being able to

support themselves. Yet others con-

tinued a trend that had evidenced even

before the war, the feeling that they

could have it all-a college education,

career, marriage, and children.

Few respondents, however, reported that

the war had caused a fundamental

shift in their attitude toward marriage

and family. The attitudinal changes that

did occur had more to do with their

college experience than the war itself. For

example, one nursing student changed her

mind about starting a family right

away because she viewed housework as

"hard work and boring," particularly

when compared to her more

"satisfying" studies and college social life. In fact

only one graduate, a 1947 one, reported

a major change directly related to the

war. Her unique response is matched by

its poignancy: "because of the war I

lost my boy friend; after graduation I

left town to teach and never married."

Even if the war years did not

substantially impact the beliefs of women

students, it is possible, that over

three years of campus life dominated by

women, and the closer female bonds this

created, produced some sympathy for

the feminist movement of the 1960s and

1970s. After all, for some the

wartime sense of female community was

exhilarating. One graduate stated

that "I found my time at UC the

happiest of my life, perhaps in part because

most of the men were at war and we had

the campus to ourselves .. ." In

fairness, however, such opinions were

exceptional, and hardly a basis for find-

ing a direct relationship between active

wartime students and the more mili-

tant feminists of the 1960s and 1970s.

The survey of Cincinnati graduates

predictably produced a variety of views

on women's rights, but there was a

surprising degree of agreement in certain

areas. Most graduates believed that

their college experiences had little impact

on the formation of their views. Instead

they credited their postwar experi-

ences in the workplace, along with their

family upbringing, with shaping

their opinions on women's rights. Almost

all agreed that there should be

equal pay for equal work and that women

should be treated as equals in the

workplace, but few identified themselves

as feminists and most took pains to

distance themselves from contemporary

feminism. On the surface it appears,

as said, that there is scant evidence of

a direct link between the World War II

college experiences and the later

emergence of feminism, although consider-

ably more exploration of the lives of

these women would be necessary before

one could make any definitive

conclusions on this complex topic.

Based on the Cincinnati experience,

several conclusions can be drawn about

the impact of the war on women in higher

education. First, it must be rec-

Women, Higher Education, and the Home

Front 57

ognized that the war affected them in

diverse ways. For some the war had lit-

tle impact. As one graduate recalls,

"I went my way, carrying as many as 21

hours, playing tennis, working. ..

" But for others "the war was an om-

nipresent factor." It is clear,

however, that Dean Ingle's prediction concerning

the revolutionary impact of the war on

women in higher education did not

come to pass.

Additionally, the war had relatively

little impact on most women's aca-

demic careers. Although it did lead to

the lowering of barriers to the entry of

women in some fields, notably

engineering, relatively few availed themselves

of the opportunity to enter

"male" fields such as engineering, the sciences,

law, or medicine. Most women students at

Cincinnati appear to have entered

the university with well-defined career

plans which the war did not cause them

to reconsider.

In a long-term sense, the war did lead

to more women attending colleges, as

the GI Bill stimulated overall

tremendous growth in university enrollment,

both at Cincinnati and nationally.

However, most veterans and new college

students were men, and women as a

percentage of the total student population

actually declined well below prewar

levels. The most that can be said for the

war is that it modestly accelerated the

century-long trend of more women at-

tending college.

The University community's attitude

about women's role in education or

society remained largely unchanged by

the war. Most male students, faculty,

and administrators viewed wartime

changes related to women as temporary,

and the war did not challenge their

fundamental views on women's proper

role. After the war, women were expected

to return to their subordinate posi-

tions within the university community

(as well as society at large), and, for

the most part, they did.

The war's impact on the attitudes of

women students is more complex, but

it does not appear that it had a

significant liberating effect. Many women

students did experience a greater sense

of female community during the war,

but they did not change their

priorities, which included putting marriage and

family ahead of career. It is perhaps

incorrect even to speak of liberation

since few women students thought in

those terms at the time. As one

alumna, who later became a

self-described militant feminist, assessed the

war's impact on her feminist

consciousness: "I cannot honestly say (and am

ashamed of this) that the war affected

my feminism. What did affect it was

the rush to marriage, family,

ticky-tacky houses and washing machines after

the war."