Ohio History Journal

DARWIN H. STAPLETON

Abraham Flexner, Rockefeller

Philanthropy, and the Western

Reserve

School of Medicine

In September 1914 the president of

Western Reserve University in

Cleveland, Charles F. Thwing, addressed

a friendly letter to an important

ally of the university's medical school:

I am glad to say to you that your

Western Reserve Medical School is opening to-

morrow in excellent form ... The

students seem to be overflowing. We have a lit-

tle larger first-year class than we

ought to receive. We, Faculty and Trustees of

both Lakeside [hospital] and the

University, are now considering, with utmost care,

the question of [future] location.

The correspondent to whom Thwing wrote

so intimately was neither one

of the great contributors to the

university nor one of the important lead-

ers of the medical school. Rather it was

Abraham Flexner, an officer of

the Rockefeller-funded General Education

Board in New York.

Thwing was neither flippant nor

overgenerous when he told Flexner that

the Western Reserve University School of

Medicine was "his," and there-

by hangs the tale of this essay.2 Beginning

in 1910, a few years before

Thwing's letter, and at a crucial point

in the school's evolution, Flexner

and Rockefeller funding had become

important actors, and for at least two

decades remained highly influential. It

was precisely during those years,

1910 to about 1930, that the school was

transformed from a regionally-

Darwin H. Stapleton is the Director of

the Rockefeller Archive Center, North Tarrytown,

New York. An earlier version of this

paper was read as the 1990 Anton and Rose Sverina Lec-

ture for the Historical Division of the Cleveland

Medical Library Association, Cleveland,

Ohio. Both versions have drawn on

research in the Case Western Reserve University

Archives by Bari 0. Stith.

1. Charles F. Thwing to Abraham Flexner,

30 September 1914, f. 7283, box 709, Gener-

al Education Board archives (hereafter

GEB), Rockefeller Archive Center (hereafter RAC),

North Tarrytown, New York.

2. The name of the Medical Department of

Western Reserve University was changed to

the School of Medicine in 1912. I shall

use the latter name throughout this paper. Frederick

C. Waite, Western Reserve University

Centennial History of the School of Medicine (Cleve-

land, 1946), 422.

|

Western Reserve School of Medicine 101 |

|

|

|

known institution in downtown Cleveland into a nationally-important in- stitution with a unified medical center in University Circle.3 Existing histories of the School of Medicine do not elaborate on the effect of Flexner and Rockefeller philanthropy, in part because the pri- mary sources for exploring the relationship were not consulted. The Rockefeller Archive Center, which houses 50 million documents deal- ing with the Rockefeller family and its philanthropies, was not opened until 1975, and scholars are only beginning to tap it to explore the im- portant role of the Cleveland-based Rockefeller fortune in a wide range of American institutions.4 Abraham Flexner is certainly one of the figures who plays dramatical- ly across the stage of Rockefeller philanthropy. Born to a Jewish immi-

3. Centennial History, esp. chs. 15-17; Clarence L. Cramer, Case Western Reserve: A His- tory of the University, 1826-1976 (Boston, 1976), 295-304; and David D. Van Tassel and John J. Grabowski, eds., Encyclopedia of Cleveland History (Bloomington, IN., 1987), 157- 59,672-74,837, 1000-02. 4. For example: John Ettling, The Germ of Laziness: Rockefeller Philanthropy and Pub- lic Health in the New South (Cambridge, MA., 1981); Gerald Jonas, The Circuit Riders: Rock- efeller Money and the Rise of Modern Science (New York, 1989); Martin Bulmer, The Chicago School of Sociology: Institutionalization, Diversity, and the Rise of Sociological |

102 OHIO HISTORY

grant family in Louisville, Kentucky,

Flexner attended and graduated from

Johns Hopkins University in the 1880s

with a degree in the classics. He

returned to Louisville for more than

fifteen years of high school teaching

and private tutoring, then went to

Harvard to study psychology. Disap-

pointed with his graduate program there,

he went to Europe for a sabbat-

ical and wrote a book critical of American

higher education.5

On his return to the United States

Flexner sought a position with the

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement

of Teaching, a new philan-

thropy established by Andrew Carnegie.

Flexner may have been advised

and aided in his approach to the

foundation by his brother Simon Flexner,

a leading American medical researcher

who had a few years earlier become

the first director of the Rockefeller

Institute in New York, the first

biomedical research center in the United

States.

As it turned out, the President of the

Carnegie foundation was inter-

ested in commissioning a survey of

American medical education, and in

Abraham Flexner he found the

intelligent, critical, informed, but disin-

terested point of view that he wanted.

After clearing the project with the

American Medical Association, Flexner

was sent out on a whirlwind tour

of over 150 medical schools in the

United States and Canada in 1909 and

early 1910.

Flexner set his task as investigating

and assessing the entrance re-

quirements, faculties, and clinical and

research facilities of each school.

He believed that he could do so rapidly,

and often needed less than a day

to review admission records, interview

faculty, and tour facilities at a sin-

gle institution. Within a year he

produced a monumentally influential

work, Medical Education in the United

States and Canada, that was high-

ly critical of much of what passed for

medical education in America.6

Flexner's findings are not complex to

relate. He wanted to reduce the

number of medical schools from about 150

to 30, because he thought that

only one-fifth had rigorous admission

standards, well-trained faculties,

and excellent laboratories and clinical

facilities. He also argued in favor

of professors being full-time, that is

without any commitment to private

medical practice, so that their

loyalties and time would be committed to

Research (Chicago, 1984).

5. For my view of Flexner and other

general material on the Flexner report and the Gen-

eral Education Board I have relied

heavily on Steven C. Wheatley's The Politics of Philan-

thropy: Abraham Flexner and Medical

Education (Madison, Wis., 1988). See

also Howard

S. Berliner, A System of Scientific

Medicine: Philanthropic Foundations in the Flexner Era

(New York, 1985) and E. Richard Brown, Rockefeller

Medicine Men: Medicine & Capital-

ism in America (Berkeley, Cal., 1979); s.v., "Flexner,

Abraham," in Who's Who in America,

1934-35 (Chicago, 1934).

6. Abraham Flexner, Medical Education

in the United States and Canada: A Report to

the Carnegie Foundationfor the

Advancement of Teaching. Bulletin no.

4. (New York, 1910);

Berliner, A System of Scientific Medicine,

108-10.

Western Reserve School of

Medicine 103

education and research. In general these

criticisms and ideas had been

around for some years, as Flexner

acknowledged, but the time was ripe for

a forceful and authoritative advocate of

reform, and he filled that role ex-

tremely well.

The effect of the Flexner report was in

some instances very dramatic.

Robert Brookings, the benefactor of the

medical school at Washington

University in St. Louis, read a

preliminary version of the report and im-

mediately asked Flexner to visit the

school with him to point out its defi-

ciencies. Within two days Brookings

pushed through the board of trustees

reforms on the lines Flexner had

suggested.

The Flexner report was extremely

favorable to Western Reserve Uni-

versity's school of medicine. The school

had ten years earlier adopted the

stiffest level of entrance standards in

the United States-three years of col-

lege preparation-and had for several

years had its laboratory courses

taught by full-time professors, with

excellent facilities provided for them.

Flexner had high regard for the school's

affiliation with Lakeside Hospi-

tal, and throughout his report cited it

as a model for clinical relationships.

For more than a decade the university

had nominated the staff of the hos-

pital and had exclusive teaching

privileges there.7

The general impact of the Flexner report

on American medical educa-

tion was slight at first because its

recommendations were not adopted for-

mally by state medical boards or by

medical associations. However, it had

enormous impact over the next decade and

beyond, and the Flexner report

became the bible of the Rockefeller

philanthropies that massively sup-

ported American medical schools: it has

been estimated that they provided

60 percent of the foundation aid to

medical education from about 1910-

1930. Their promotion of medical

research and full-time faculties trans-

formed medical education into its modern

form in the United States.8

Flexner's influence became very strong

when in 1912 he accepted a per-

manent position with the General

Education Board, a philanthropic foun-

dation created in 1902 by John D.

Rockefeller to support the orderly

growth of higher education and the

reform of public school education in

the American South. Rockefeller

eventually gave the board $129 million

for its endowment.9 This

organization should not be confused with the

Rockefeller Foundation, established by

John D. Rockefeller in 1913 as the

largest general-purpose foundation

created in the first half of the twenti-

7. Flexner, Medical Education, esp.

106, 285-86; Waite, Centennial History, 249. See also

B.L. Millikin to S.T. Murphy [sic], 15

March 1905, f. 6637, box 631, GEB.

8. Wheatley, Politics of

Philanthropy, 112.

9. The General Education Board: An

Account of its Activities, 1902-1914 (New

York,

1930), 3-9; John Ensor Harr and Peter J.

Johnson, The Rockefeller Century (New York, 1988),

70-81,562.

104 OHIO HISTORY

eth century. During the period covered

here, 1910-1930, it was the Gen-

eral Education Board, Flexner's

organization, not the Rockefeller Foun-

dation, that was the major actor in

American medical education.

Now that the outside actors have been

described, let us see how the his-

tory of the medical school was

influenced by Abraham Flexner and Rock-

efeller philanthropy.

The Western Reserve University school of

medicine was founded in

Cleveland in 1843, and operated as a

rather autonomous unit until 1893

when growth in the school's endowment

permitted the creation of full-time

professorships in the laboratory

departments. Thereafter the university had

increasing financial oversight of the

school, and the school turned in the

direction of scientific medicine. A

physiological laboratory was erected

in 1898, and the Cushing Laboratory of

Experimental Medicine was

opened in 1908 as a result of the gifts

of Cleveland industrialists Howard

M. Hanna and Oliver H. Payne. The

laboratory scientists at the school

quickly compiled an enviable record of

publications in nationally-promi-

nent journals, including the Journal

of Experimental Medicine, which had

been founded at Johns Hopkins in 1896

and transferred to the Rockefeller

Institute in 1905.10 The clinicians at

the school were outstanding as well.

George W. Crile, for example, was known

for his highly successful sur-

gical technique, and for his important

and respected publications.

When Rockefeller philanthropy entered

this situation it was largely in

an attempt to preserve and expand the

strong teaching environment that

already had been created. John D.

Rockefeller, who had grown up in Cleve-

land and had founded his fortune on his

business activities there, was aware

of the growth of higher education in

Cleveland and had long been inter-

ested in Cleveland medicine. His

benefactions ranged from contributions

to the association that bought the land

for the adjoining Western Reserve-

Case campuses, to the construction of

the Mather dormitory for the Col-

lege for Women, the funding of the

physics building for Case, and to the

Cleveland Medical Library Association.

Having a homeopathic orienta-

tion, in the 1880s and 1890s Rockefeller

supported the Cleveland Home-

opathic Medical College through his

personal physician, Hamilton F. Big-

gar. (There is not space to discuss here

the role of Rockefeller philanthropy

10. Millikin to Murphy, 15 March 1905,

loc. cit.; George W. Corner, A History of The

Rockefeller Institute, 1901-1953:

Origins and Growth (New York, 1964),

62-63; H.M. Han-

na to E.F. Cushing, 14 November 1906,

extract, box 18, Charles F. Thwing Office Files (here-

after TOF), Case Western Reserve

University Archives (hereafter CWRU Archives), Cleve-

land, Ohio.

|

Western Reserve School of Medicine 105 |

|

|

|

in practically every area of Cleveland's educational, cultural, and educa- tional institutions.)11 As the twentieth century dawned, however, Rockefeller's son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and his philanthropic advisor Frederick Gates persuaded Rockefeller that modern medical research and allopathic medicine held the greatest promise for alleviating or eradicating the endemic and epi- demic diseases that were, according to reformers of the era, the causes of much social misery and vice. Rockefeller founded the Rockefeller Insti- tute for Medical Research in New York in 1901, the first American med- ical research institution devoted solely to research into human physiolo- gy and the fundamental causes of illness, and the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease, established in 1909 to work in the American South. Rockefeller's interest was first drawn to the Western Reserve Univer- sity School of Medicine when Starr J. Murphy, his financial advisor and a trustee of the General Education Board, visited Cleveland in 1905 to ex- amine Rockefeller philanthropic commitments. He wrote a 30-page report to Rockefeller describing Western Reserve University, and especially its medical school, concluding that "This is the best Medical School I have

11. The author's A History of University Circle: Community, Philanthropy and Planning in Cleveland, 1800-1985 will be published by Ohio State University Press. |

106 OHIO HISTORY

seen except Harvard and Johns Hopkins.

The professors and instructors

are in the main from those institutions

and have brought with them the tra-

ditions and practices of those

institutions."12

It was four years later, just before

Abraham Flexner came to survey the

school for his famous report, that

President Thwing made an appeal to the

General Education Board. He asked for

$250,000 toward a proposed

$1 million endowment for the school of

medicine. Howard Hanna, a lead-

ing Cleveland industrialist, had given

$250,000 a year before, but the

endowment campaign had stalled. Thwing

played on the known prejudices

of the Rockefeller philanthropies by

emphasizing the school's high ad-

mission standards and its commitment to

laboratory science. He was able

to point to the recent creation of the

Cushing Laboratory as an example

of what he called "this

indispensable association" of "laboratory and clin-

ical research" which have

"continually ... become closer."13

The General Education Board asked Simon

Flexner, director of the

Rockefeller Institute and co-editor of

the Journal of Experimental

Medicine, to review Thwing's proposal, and he replied favorably

with-

out hesitation.

I believe that the Medical Department of

Western Reserve University is one of the

most modern and progressive faculties in

the country. The scientific chairs in the

Institute have now for several years

been on a university basis, and have been filled

with men of distinction. The

Laboratories have devoted for many years a consid-

erable part of their energies to

research and have been productive in a highly com-

mendable degree ... In other words, I

have a high opinion of the Medical Depart-

ment of Western Reserve University and

believe that it is moving in the right

direction ....14

The General Education Board's secretary,

Wallace Buttrick, presented

Thwing's request to the board's trustees

favorably, but they decided that

they were already overcommitted to

undergraduate colleges and were not

prepared to support professional

schools. Frederick Gates, however, rec-

ommended that the $250,000 be given by

Rockefeller personally, and the

request was passed along through Starr

Murphy and John D. Rockefeller,

Jr. 15 Rockefeller apparently

replied favorably, but suggested that a con-

12. Starr J. Murphy to John D.

Rockefeller, 27 April 1905, "Western Reserve Universi-

ty" file, box 121, Education

series, RG 2, Rockefeller Family archives, RAC.

13. Charles F. Thwing to General

Education Board, 14 October 1909, f. 6637, box 631,

GEB; Waite, Centennial History, 382.

14. Simon Flexner to Starr J. Murphy, 21

March 1910, "Western Reserve University" file,

box 121, Education series, RG 2.

15. Starr J. Murphy to Wallace Buttrick,

29 March 1910, f. 7283, box 709, GEB; Starr J.

Murphy to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., 18

April 1910, "Western Reserve University" file, box

121, Education series, RG 2.

Western Reserve School of

Medicine 107

dition of the gift be that the school be

required to teach homeopathy. Starr

Murphy replied firmly that "to

prescribe that a given theory of medicine,

or a given school of practice, must be

taught would go counter to our best

modern tendencies, and would involve

grave danger that the fund might

become wholly useless and even

pernicious."16

A few months later Rockefeller decided

to make the $250,000 contri-

bution without any reference to

homeopathy, and gave the university from

October 1910 until the end of December

1911 to raise a matching

$750,000.17 During the next year Thwing

worked assiduously to reach the

required sum, and by the end of 1911

reached the $1 million goal with

gifts of $100,000 each from Samuel

Mather and Oliver Payne, and twen-

ty-eight gifts of $50,000 or less from

other Cleveland business and phi-

lanthropic leaders.18

The success of Rockefeller's gift to the

school seems to have been an

important stage in the association of

Rockefeller philanthropy and med-

ical schools. Never previously had John

D. Rockefeller or his philan-

thropies given to the endowment of a

medical school, but the gift to West-

ern Reserve University-a challenge grant

to an institution committed to

scientific research and full-time

professorships--became the model. As

so often happened in Rockefeller

philanthropy, John D. Rockefeller's pri-

vate action (and later that of his son,

John D. Rockefeller, Jr.) pioneered

a policy that was carried out globally

or nationally by one of his philan-

thropic organizations.

In this case, the General Education

Board up to 1910 had been focused

on the improvement of secondary school

education in the South, higher

education for blacks, and developing the

endowment of a few leading col-

leges. But what happened with Western

Reserve University, and the con-

tinuing flow of millions from

Rockefeller, provided the impetus to broad-

en the board's agenda. When the board

hired Flexner late in 1912 they

knew he was bringing a strong vision of

how to improve medical educa-

tion through philanthropy.19

Flexner began to assert his new role in

the spring of 1913 when he was

appointed to a General Education Board

committee that was "to make a

16. Starr J. Murphy to John D.

Rockefeller, Jr., 2 May 1910, "Western Reserve Univer-

sity" file, box 121, Education

series, RG 2. Rockefeller had several years earlier shown his

concern regarding homeopathic

instruction in the controversy regarding the affiliation of

Rush Medical College with the University

of Chicago: Berliner, A System of Scientific

Medicine, 39-41.

17. Starr J. Murphy to Charles F.

Thwing, 4 October 1910, "Western Reserve Universi-

ty" file, box 121, Education

series, RG 2.

18. Charles F. Thwing to Starr J.

Murphy, 11 January 1912, "Western Reserve Univer-

sity" file, box 121, Education

series, RG 2.

19. Raymond B. Fosdick, Adventures in

Giving: The Story of the General Education Board

108 OHIO HISTORY

careful study of clinical instruction in

medical schools."20 Although ap-

parently the committee planned to visit

only Harvard and Johns Hopkins,

the word of its mission seems to have

leaked to Cleveland, for in Septem-

ber George Crile, a member of Reserve's

faculty and, perhaps, Cleveland's

most eminent physician, invited Flexner

to "run out here to look over our

medical college and Lakeside Hospital

situation to give your advice

about the size of classes."21

Flexner came with Wallace Buttrick, presi-

dent of the General Education Board, and

addressed a planning meeting,

probably the medical school's committee

on the future location of the

school and Lakeside Hospital. Afterward

Thwing thanked him for estab-

lishing the "general

principles" for their plans.22

Flexner's advice was sought, first,

because Thwing and others had high

hopes for further Rockefeller support of

the School of Medicine and, sec-

ond, because Flexner's insistence on the

importance of consolidation of

medical schools with clinical facilities

corresponded well with the goals

of Cleveland's medical and business

leaders who wanted to associate more

closely the school of medicine, Lakeside

Hospital and possibly other

Cleveland hospitals.

Plans for an organic association of

these bodies had become serious two

years before when Thwing and Samuel

Mather, as president of the trustees

of Lakeside Hospital, had agreed to plan

the future of their institutions to-

gether.23 To Cleveland

philanthropists this seemed the only route to effi-

ciency and excellence of service. As

Howard Hanna put it: " A Medical

School cannot reach, or maintain, a high

standard, without a close affili-

ation with an up-to-date Hospital.

Without that affiliation accomplished

between the ... Medical school, and the

Lakeside Hospital, my interest and

support of the Medical School would

cease."24 With this kind of support

the affiliation was a fait accompli: in

1913 the University Medical Group

was formed consisting of the School of

Medicine, Lakeside, and the Ba-

bies and Childrens' Hospital.25 But

plans for a new downtown complex

of buildings for these institutions

foundered. Early in 1914 Samuel Math-

er raised serious questions about its

location.26 As he explained it a year

later in his report to the Lakeside

trustees:

(New York, 1962), 150-60; 25 October

1912, trustees' minutes, GEB.

20.23 May 1913, trustees' minutes, GEB.

21. George W. Crile to Abraham Flexner,

[September 19131, f. 7283, box 709, GEB.

22. "Report of the Faculty

Committee on the location of the Medical School and Hospi-

tals," 22 September 1913, box 18

TOF; Charles F. Thwing to Abraham Flexner, 16 December

1913, box 18 TOF; Abraham Flexner to

Edwin P. Carter, 9 June 1914. f. 7283, box 709, GEB.

23. Howard M. Hanna to Charles F.

Thwing, 5 December 1911, box 18, TOF.

24. Howard M. Hanna to Charles F.

Thwing, 12 December 1911, box 18, TOF.

25. Van Tassel and Grabowski, eds., Encyclopedia

of Cleveland History, 1001.

26. 30 January 1914, minutes, joint

committee on hospital and medical school buildings,

box 18, TOF.

Western Reserve School of

Medicine 109

A year ago we were confidently planning

the establishment of a large Hospital-

Medical group in our present [downtown]

location ... The unexpected discovery,

however, that in connection with the

proposed new Union Depot, the railroads were

planning to very largely multiply their railroad tracks

in front of the Hospital, and

also to elevate them sixteen feet above

their present level, aroused in the minds

of all ... an apprehension [regarding]

... the resulting increase in noise and smoke

from the increased number of tracks and

trains passing between our building and

the lake ...27

A substantial debate over the new

location ensued that had an unex-

pected relationship to the full-time

issue for the clinicians. Some profes-

sors and trustees argued that only a

downtown site would be accessible for

a substantial number of patients and

convenient to professors with private

practices: some of the clinical

professors feared that a site on the periph-

ery of the city would make it impossible

to serve their clientele and would

certainly reduce their incomes. They

were probably right. A few years lat-

er Harvey Cushing, a leading Boston

surgeon who had become a full-time

professor at Harvard, stated that

"Happy full-time people are either bach-

elors or people of independent means ..

.I suppose my take-in is about one-

fifth of what what it would be if I

wanted to go out for the full emoluments

which my special training would

bring."28

Throughout the deliberations on the site

and "full-time," Thwing,

Mather, and Crile kept Flexner informed.

When the process seemed stale-

mated in the spring of 1914 they invited

him to Cleveland to address the

concerned parties, and particularly to

deal with the concerns of the med-

ical school faculty. Flexner came armed

with a thorough knowledge of the

debate through documents sent to him.29

His talk emphasized the impor-

tance of full-time instruction and urged

Western Reserve to follow the re-

forms recently initiated at Johns

Hopkins, Yale, and Washington Uni-

versity with the aid of General

Education Board grants. Although his talk

was eloquent about the great

possibilities for reform in medical education,

Flexner was also frank. He said:

"Certain practical questions arise in con-

nection with the full-time scheme. You

may be interested in the details of

their tentative solution. The full-time

clinician will practically live in the

hospital laboratories and the

wards."30

Afterward Professor David Marine, a

pathologist at the school of

medicine and a graduate of Johns

Hopkins, told Flexner that he had done

27. Samuel Mather, "Report of the

President of Lakeside Hospital to the Annual Meet-

ing of the Corporation, 1915,"

University Hospitals archives, Cleveland, Ohio.

28. Harvey Cushing to Richard M. Pearce,

1 May 1920, f. 11, box 2, series 906, RG 3,

Rockefeller Foundation archives, RAC.

29. David Marine to Abraham Flexner, 13

June 1914, f. 7283, box 709, GEB; George W.

Crile to Abraham Flexner, 13 June 1914,

ibid.

30. Abraham Flexner, [after-dinner

address], [c. 18 June 1914], f. 7283, box 709, GEB.

110 OHIO HISTORY

"a great service" to "the

cause of higher medical education in Cleveland."

Specifically, Marine said, "as a

result of your presence here, men who a

few months ago were anxiously looking

about for avenues of escape are

now enthusiastic, encouraged, and glad

to be in a position to render ser-

vices towards obtaining a better Medical

School."31 But the situation was

not so easily resolved, because the medical

school faculty and the Lake-

side trustees could not agree on a new

site for the combined institutions.

In October 1914 Samuel Mather wrote

urgently to Flexner asking him to

return again to "give us the aid of

your experienced judgment."32 Flexner

instead invited Mather to visit him in

New York, and over the next few

months he also had visits from Crile and

Thwing.33

The full-time issue for clinical

professorships was resolved diplomat-

ically, as Thwing informed Flexner, by

creating full-time positions for new

appointments forjunior faculty beginning

in 1916, but retaining part-time

teaching positions for current faculty.

This avoided the problems experi-

enced at Johns Hopkins and other

institutions where venerable clinicians

were forced to make a painful choice

between private practice and full-

time teaching.34

Along with this compromise came

agreement to build the new medical

center on a site adjacent to the Western

Reserve University campus.

Flexner now became a consultant on the

architectural plans for the com-

plex. He returned to Cleveland once more

in June 1916 to go over the de-

sign with Howard Hanna, and again gave a

luncheon address on the de-

velopment of the full-time plan.35 Flexner

avoided making any

commitment to financial support of the

venture, but assured Mather that

the General Education Board regarded the

school "as one of the most hope-

ful spots in the country from the

standpoint of medical education."36

Interestingly enough, Charles A.

Coolidge of Boston, the architect who

had drawn the plans for the Medical

School and for Lakeside Hospital that

Flexner was called on to review, had

earlier designed the buildings of the

Rockefeller Institute in New York, and

had just been commissioned to de-

sign the Rockefeller-financed Peking

Union Medical College in China.

31. David Marine to Abraham Flexner, 19

June 1914, f. 7283, box 709, GEB.

32. Samuel Mather to Abraham Flexner, 7

October 1914, f. 7283, box 709, GEB.

33. Abraham Flexner to Samuel Mather, 17

October 1914; George W. Crile to Abraham

Flexner, 31 December 1914; and Charles

F. Thwing to Abraham Flexner, 25 May 1915, all

in f. 7283, box 709, GEB.

34. Charles F. Thwing to Abraham

Flexner, 25 May 1916, f. 7283, box 709, GEB; Waite,

Centennial History, 402; Wheatley, Politics of Philanthropy, 67-68,

97-98; Berliner, Sys-

tem of Scientific Medicine, 150-61.

35. Charles F. Thwing to Abraham

Flexner, 24 June 1916 and 12 October 1916, f. 7283,

box 709, GEB; Samuel Mather to Abraham

Flexner, 14 July 1916, f. 7283, box 709, GEB.

36. Abraham Flexner to Samuel Mather, 17

July 1916, f. 7283, box 709, GEB.

Western Reserve School of

Medicine 111

Coolidge was known to Clevelanders for

his design of the largest office

building in the city, the New England

Building, and already had a repu-

tation as an architect of academic

buildings, but his close connection with

Rockefeller interests could have

influenced the decision to employ him.37

This is not the place to follow in

detail the progress, or lack thereof, of

the medical center idea over the years

from 1916 to 1922. But quite sim-

ply, although the trustees of the

University and the hospitals elaborated

and refined the plans for the complex,

the price tag of some ten to fifteen

million dollars daunted them, especially

during the war years and post-

war recession. Samuel Mather made an

initial gift of $300,000 to the pro-

ject in 1917, and Thwing hoped, with

Flexner's support, to get a large sum

from the Rockefeller or the Carnegie

philanthropies to make the total

achievable.38 But neither made

a contribution to the endowment, despite

the pleas of Thwing and, after his

retirement in 1921, the new university

president Robert E. Vinson.

Instead it was Samuel Mather' s decision

to make a personal commitment

to the construction of the medical

school building in 1922 that put the

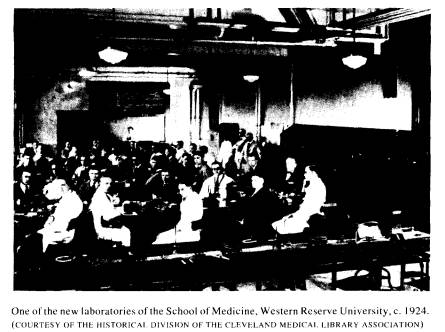

wheels in motion. The Medical School

building opened in 1924 at a cost

of $2.5 million, and the Babies and

Childrens and Maternity Hospitals were

completed a year later. Lakeside Hospital

opened in 1931. These achieve-

ments were entirely the result of

contributions from Clevelanders.39

Vinson was finally able to obtain

General Education Board participa-

tion in the medical center by convincing

Flexner to support the universi-

ty's request for $750,000 for the

construction of the Institute of Patholo-

gy building, which opened in 1928.

Almost as important, in 1927 the board

began to give the medical school a grant

for operating expenses, begin-

ning with three annual appropriations of

$75,000. Vinson had told the

board in 1925 that the medical school

had expenditures of about $300,000

but an income of only $175,000. The

endowment of the medical school

had grown only slightly since the $1

million campaign of 1910-11 to which

John D. Rockefeller had personally

contributed.40

In all, however, by 1929 the medical

school and the associated medi-

cal institutions had come a remarkable

distance since Thwing had asked

37. Corner, Rockefeller Institute, 55;

Mary E. Ferguson, China Medical Board and Peking

Union Medical College (New York, 1970), 30-32; Henry F. Withey, Biographical

Dictio-

nary of American Architects

(Deceased) (Los Angeles, 1970),

136-37.

38. Charles F. Thwing to Jeptha H. Wade

II, 1 February 1917; Charles F. Thwing to Samuel

Mather, 23 July 1918; Samuel Mather to

Charles F. Thwing, 31 July 1919, all in box 18, TOF.

39. Waite, Centennial History, 421-22,426.

40.3 December 1925 and 4 February 1926,

Richard M. Pearce diary, RG 12, Rockefeller

Foundation archives, RAC; Robert E.

Vinson to Abraham Flexner, 2 December 1925; Robert

E. Vinson to Abraham Flexner, 4 October

1926; W.W. Brierley to Robert E. Vinson, 22

|

112 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

for General Education Board support in 1909. On a visit to Cleveland ear- ly in October 1929, Dr. R.A. Lambert, an officer of the General Educa- tion Board, examined the medical school in order to consider whether to recommend it for a continuation of its annual operating grants. On virtu- ally every score he found it a model of the kind of medical education the board wanted to promote. Extracts from his assessment are a neat and glowing summary of the accomplishments at the medical school over the previous twenty years:

The laboratories of the Medical School are not merely ample; they are splendid- ly organized and equipped ... The new Institute of Pathology indeed surpasses in completeness any other in the United States ... The Medical Faculty is unusually strong. With a few exceptions the heads of departments are leaders in their re- spective fields ... [the school] is setting the pace in academic salaries ...

The community support of the Medical School and University as judged by gifts in the past five years, has hardly a parallel in the United States ... The new Med-

November 1926; Robert E. Vinson to W.W. Brierley, 24 November 1926; Robert E. Vin- cent to Abraham Flexner, I April 1927, all in f. 7284, box 709, GEB. |

Western Reserve School of

Medicine 113

ical Center is made up of a group of

well-planned, well-organized, well-equipped

institutions located in the center of

the University campus."41

This assessment must have mightily

pleased the General Education

Board and especially Abraham Flexner,

who had just retired.

***

Flexner's role in the development of the

school of medicine suggests

the importance of ideas in history. Even

though the school had established

its own commitment to the scientific

direction of modern medicine, its

leaders found it very important to call

on Flexner to articulate the call to

full-time professorships and to the

importance of an integrated medical

complex in a university setting. What

Flexner brought to Western Reserve

was a connection with the broader

currents of medical education in the

United States, and nurturance of the

faith that Clevelanders had progres-

sive-minded colleagues who shared their

goals. These ideas, which Flexn-

er presented authoritatively, were

critical to moving the discussions and

the decision-making process forward.

In a similar way, Rockefeller's personal

act of philanthropy in 1910

demonstrates the power of money when

used as a lever. We do not know

the extent to which Rockefeller was

apprised of the school of medicine's

inability to develop support for its

million-dollar endowment campaign,

but his "challenge grant" (as

we would call it today) was an effective cat-

alyst and put the whole process of

creating the University Hospitals

Group onto a new footing. It is clear

that philanthropy, often regarded as

either simple charity or as

self-aggrandizement, can also be a tool for in-

stitutional change and development. In

the case of the relocation and ex-

pansion of Western Reserve University's

school of Medicine, Rockefeller

philanthropy had a vital role in the

conception and planning of a model

medical complex.

41. R.A. Lambert, "Western Reserve

Medical School," 24 October 1929, f. 7284, box 709,

GEB.