Ohio History Journal

| Winter-Spring

2003 pp. 19-26 |

||

|

Copyright

© 2003 by the Ohio Historical Society. All rights reserved.

|

||

|

A High School

to Remember: |

||

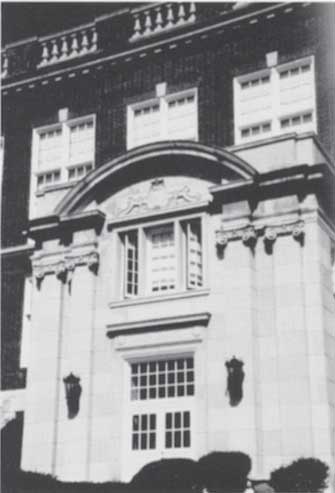

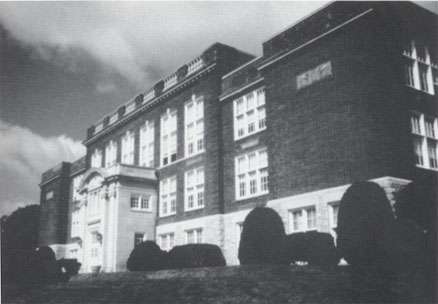

McClain High School, Greenfield, Ohio. (Photo courtesy Virginia E. McCormick.) |

||

|

As Supreme Court justices, legislators, and educators begin the twenty-first century wrestling with equitable funding for Ohio schools and the School Facilities Commission allocates funds and monitors guidelines for school construction, there is much to be learned from the Greenfield, Ohio, legacy of Edward and Lulu McClain, Frank R. Harris, and William B. Ittner. Their vision created an educational complex that dramatically validates the strength of cooperative effort between enlightened community leaders, dedicated educators, and innovative architects. The survival of this educational complex begun in 1914 is testimony both to a community’s commitment to preserve the heritage that attracted national attention and the building’s practical utility for facilitating current educational purposes. Edward Lee McClain was a Greenfield native son, born on the eve of the Civil War, who began working in his father’s harness and saddle shop at the age of thirteen. There he invented a horse-collar pad with an elastic steel hook which allowed it to be readily attached and detached from the horse collar. This innovation quickly became so popular that it dominated the market, and when McClain’s manufacturing company incorporated as The American Pad and Textile Company in 1903, its 360,000 foot “TAPATCO” plant at Greenfield was producing one thousand dozen pads per day. As horses gave way to automobiles early in the twentieth century and the country mobilized for the First World War, TAPATCO made a transition to life preservers.1 Shortly before McClain retired in 1913, he confided to the Greenfield High School principal, Frank Raymond Harris, his philanthropic goal of providing his hometown with a state-of-the-art high school. Harris, also a Greenfield native, graduated with the class of 1897 and from Ohio Wesleyan University before becoming principal of his hometown high school in 1903.2 He was an idealist who became well acquainted with the latest educational theory and practice while earning a masters degree from Harvard University in 1911. It was a dramatic time in terms of educational progress, motivated by the philosophy of John Dewey that the United States must provide universal education to prepare citizens to participate effectively in our democratic society.3 Dewey and others placed particular emphasis on abilities to contribute economically in an increasingly industrial society. During the last decade of the nineteenth century and the early years of the twentieth century the Ohio General Assembly enacted a series of laws relating to secondary education. In 1892, the Boxwell examination was created to standardize requirements fo students from rural districts with no high school so that they could attend a nearby high school. The 1902 Brumbaugh Law defined standards for secondary education and created classifications for high schools based upon their size and curriculum. In 1909, school districts were authorized to offer optional vocational courses in agriculture, business, and domestic science. In 1914, sweeping administrative changes were made by creating county superintendents and a state superintendent for public instruction to be appointed by the governor.4 Education was maturing as a profession, and so was architecture. The Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 sparked a revival of classical architecture and introduced an era of urban planning known as the “City Beautiful” movement.5 This coincided with a tragic educational event, the Lakewood School fire at Collinwood, a Cleveland suburb, in March 1908 which killed 172 students and two teachers.6 Safety concerns quickly led to legislation nationwide and a massive school construction program. Architects began replacing the imposing multi-storied Victorian edifices of the late nineteenth century with two-story Neo-Classical buildings with multiple exits and raised basements with windows. As educators began working in partnership with architects, they soon developed a specialization in school architecture. At Harvard, Frank Harris had been introduced to the “open plan” school being advocated by William B. Ittner, a St. Louis architect who was becoming recognized as one of the most innovative of educational architects. A St. Louis native, Ittner had graduated from that city’s Manual Training School at Washington University and then from the Cornell University School of Architecture in 1887. He returned to practice in St. Louis, and in 1897 was appointed its Commissioner of School Buildings. Before his death in 1936 he designed some 430 schools in twenty-eight states and was eulogized as “the most influential man in school architecture in the United States.”7 It was a Greenfield, Ohio, philanthropist and high school principal who gave him the commission for the building that would establish his reputation firmly on the national stage. A key innovation of Ittner’s designs was a corridor with classrooms confined to one side, a practice he first observed on a research trip in western Germany. Utilizing a facade with perpendicular wings in a U, H, or E configuration suitable to the site, Ittner sought to maximize exterior walls and thus the available light and air in each classroom. Harris and McClain quickly determined that Ittner was the architect to execute their dream for Greenfield—a school whose environment would be a “character-building force.”8 At the time, Greenfield was the quintessential Midwestern town with tree-shaded streets flanked by comfortable homes for a population approaching six thousand persons. Upon learning, in December 1912, that Edward McClain intended to present the town with a completely equipped new high school building, the Greenfield Republican dubbed it “Greenfield’s Christmas Gift.”9 By the time the cornerstone was laid in May 1914, local citizens had a glimpse of the architect’s vision for a Georgian Revival structure providing “dignity, nobility and restraint.”10 When Edward Lee McClain High School—a name determined by the school board during the summer without McClain’s knowledge—was dedicated September 1, 1915, it would have been difficult to exaggerate the community’s pride. The new building was a dignified two-story brick in Georgian Revival style which met modern safety regulations with a raised basement of random ashlar local stone and multiple center and corner exits.11 The Jefferson Street facade featured a seven-bay projection crowned by a carved stone balustrade on a dentilated entablature. The main entry displayed a classical frontispiece crafted from Bedford stone, featuring double pilasters with Ionic capitals, a double doorway beneath a tripartite window crowned by a decorative cartouche and a segmental pediment.

An integral part of the McClains’ philanthropy was to create a visual expression of Greenfield’s aspiration to culture. This is reflected on the building’s exterior by four Moravian tile panels accenting the building’s corners, each with an inspiration¿l Latin inscription such as ARS CORONAT LABOREM—“Art Crowns Labor.” These are products of the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works established by Henry Chapman Mercer at Doylestown, Pennsylvania.12 Most of the artistic treasures of McClain High School, however, are inside, beginning with the reproductions of Michelangelo’s tomb monuments of Lorenzo and Guiliano de Medici from the San Lorenzo Chapel in Florence that flank the marble stairs of the main entrance.13 Even today, high school tradition reserves the privileged use of these marble entry stairs to graduating seniors, who at the top come face to face with “Ginevra,” an original marble bust by Hiram Powers of the vivacious Italian maiden whose zest for life was not unlike the high school students who pass her daily.14 These are but three of the 165 paintings and sculptures that adorn the interior, most selected and donated by Mrs. McClain, the former Lulu Theodosia Johnson, in consultation with Theodore M. Dillaway, Director of Art Education in Boston.15 The intent was not only to make the corridors virtual art galleries, but to provide a resource that complemented instruction in literature, history, geography, civics, music, even astronomy and chemistry. Mrs. McClain, a Cincinnati native and a graduate of Hughes High School, was undoubtedly influenced by the Art League inaugurated by its art teacher, Miss Brite, to involve students and citizens in procuring art for Cincinnati schools.16 As with several Cincinnati schools, each floor of Greenfield McClain High School features porcelain drinking fountains embellished by backsplashes of Rookwood Pottery tiles creating scenic designs.17 The breadth of the building’s art collection offers testimony to its purpose as an educational reference: busts of literary lions from Shakespeare to Robert Burns in the library, Gilbert Stuart’s paintings of George and Martha Washington, Violet Oakley’s “Constitutional Convention” and “Lincoln at Gettysburg,” the frieze of the Parthenon reproduced along the main corridor, and varied painting styles from Rembrandt’s “Sweeping Girl” to Nuehuys’ “Sewing Lesson,” Salisbury Tuckerman’s “Old Ironsides,” and Frederick Remington’s “Advance Guard.”18 Most of the nearly two hundred works are, of course, reproductions, but three large murals by Boston artist Vesper Lincoln George were painted specifically for McClain School. “Apotheosis of Youth,” a 12' by 24' mural above the main entrance, represents the service of education in the evolution of the citizen. Two forty-foot murals at either end of the library, “The Pageant of Prosperity” and “The Melting Pot,” reflect the Americanization of immigrants and the prosperity for which all persons strive.19 The U-shape of the McClain High School building incorporates Ittner’s trademark courtyard between wings, which in this instance contained an auditorium on one side and gymnasium on the other. Because Edward and Lulu McClain and Frank Harris envisioned he school serving the entire community—adults as well as youth—the auditorium was built with a separate entrance to extend its use beyond school hours. Besides accommodating school programs, it also served the town as theater and concert hall with opera-style seating for one thousand persons, ceiling lights with Tiffany globes, a pipe organ installed by the Ernest M. Skinner Company of Boston, and equipment for projecting motion pictures or carrying radio broadcasts—the newest technology of the day.20 The 63' by 80' gymnasium with maple flooring contained “spectator galleries” to seat three hundred persons. It was connected to the auditorium by a bridge on the top level, and each had a flat roof whose tiled terraces with bench seating accommodated social functions as well as horticultural and floricultural projects for the agricultural classes. McClain High School might seem like a dream come true, but Harris was a true visionary with even larger dreams. By 1923, when he was promoted to superintendent, Greenfield citizens had voted to tax themselves to build a complementary elementary school fr kindergarten through sixth grade, and Edward and Lulu McClain agreed to complete the educational complex by financing a vocational building that would take advantage of the federal funding for teachers and equipment made available by the Smith-Hughes Vocational Education Act of 1917.21 Buildings adjoining the high school were razed and streets closed to create a fourteen-acre “campus” in the heart of town. Ittner designed the elementary and vocational buildings in complementary Georgian Revival style and connected all three buildings with pergola-covered walkways. The focal point of the central courtyard was a circular stone pool with a statuary fountain. The complex also included three cottages for the caretakers who maintained the buildings and grounds. The elementary building contained eighteen classrooms to serve 1,200 students in a “platoon system” where students spent approximately half their time in their regular classroom and half in specially equipped rooms for music, handicrafts, or nature studÍ. Like the high school, it contained a library, auditorium, and gymnasium, as well as a health clinic staffed by a school nurse who taught basic hygiene and gave each student an annual health examination.22 The vocational building included three agricultural rooms, a three-room domestic science department with separate laboratories for cooking and sewing, a three-room manual training facility with woodworking and metalworking shops, a print shop, and industrial art studio. Because such a facility would attract many students from outside the town, it also included a 250-seat cafeteria. But the wonder of wonders was the natatorium with a 32' x 75' tiled swimming pool with seating for eight hundred spectators.23 When athletic fields were expanded and a transportation garage was completed in the 1930s, the school complex covered three city blocks and had truly become Greenfield’s heart.24 It was not just the largest school swimming pool in the United States that attracted the nation’s attention. In 1922 the U.S. Department of Education featured McClain High School as the frontispiece of its bulletin “High School Buildings and Grounds,” praising its fourteen-foot wide main corridors for contributing to fire safety while simultaneously serving as art galleries with their sculptural friezes.25 Greenfield proudly hosted visiting educators from throughout the country, and Ittner and Harris were frequently asked whether such facilities could be replicated elsewhere. The total cost of the three buildings—excluding grounds and equipment—was $950,000 and could accommodate 2,200 students. This averaged $432 per student in an era when many school districts were spending as much as $1,000 per pupil to construct far less spectacular educational environments.26 In 1921 the Ohio legislature had passed the Bing Act making school attendance compulsory for all youth from six to eighteen years of age—or sixteen if employed—and required rural districts to operate a high school or pay tuition and provide transportation to an adjacent high school.27 Greenfield was in position to attract and serve students from many outlying rural schools, and the funding that accompanied them helped support facilities such as the cafeteria and a broad-based vocational curriculum. Harris praised the benefits of such consolidation—an extremely controversial issue in the early part of the twentieth century—for its ability to attract high-quality teachers and offer a broad-based curriculum.28 Greenfield had anticipated by nearly a half century the legislation that would eventually create joint vocational districts which were permitted to cross county lines and city boundaries. It is impossible to calculate what the Greenfield school complex meant individually and collectively to generations of Greenfield students. A member of the 1936 graduating class—the first to begin school in the new elementary building—recalled more than sixty years later that no one walked on the grass or cut through the hedges without risking a paddling from the athletic director. Never having seen any other high school, he was not awed by McClain, but proudly recalled a visiting Chicago superintendent who admired the giant murals and literary busts in the library and declared it “the most beautiful schoolroom in America.”29

* * * * * *

Beyond the legacy the McClains, Harris, and Ittner created for the city of Greenfield, it is relevant to question whether there are conclusions to be drawn from the development of the Greenfield educational complex that offer inspiration to other communities nearly a century later. Educational vision. No one recorded whether the Greenfield school complex began as the joint dream of Edward McClain and Frank Harris or whether a comment by one spurred the other, but it would be naive to believe that the result did not derive from a carefully designed plan. Harris’s bold goal was to create a magnet school that would serve both youth and adults, not only within the town but from surrounding rural areas. Edward McClain was vitally concerned for developing an educated and productive work force, and Lulu McClain was equally determined that the citizens of her hometown be enriched by an appreciation of the liberal arts. Community leadership. Although it would be impossible in current economic conditions for an individual to play the philanthropic role the McClains contributed to Greenfield, the important role of community leadership cannot be overemphasized. Current practices of depending primarily upon elected boards of education and parent-teacher organizations for this role may be limiting. The example of Edward and Lulu McClain’s innovative involvement might find modern counterparts in corporate entities or civic organizations that would adopt a building if not an entire school system. Certainly, the McClain’s extensive financial contributions established standards for long lasting quality rather than mere acceptance of the lowest competitive bid. Educational complex. By creating a campus in the heart of the community that would serve adults as well as youth, Greenfield purposely elevated the status of education. As recent educational theory and practice emphasizes lifelong learning, it is a concept being re-examinedand emulated. Within Ohio, environments such as the “Perry Community Education Village” in Lake County and the “New Albany Learning Community” in Franklin County have won national recognition. Both relied upon massive injections of money for new construction—one from the construction of a nuclear power plant, the other from a corporation for extensive residential development.30 Most communities that admire the principle will be forced to think creatively about how they might achieve this effect without starting anew. Individual and community esteem. Although Ittner’s buildings were not the most expensive construction of their day, spaces—whether library, laboratory, or gymnasium—were specifically designed to enhance learning not only with quality equipment, but by creating an aesthetically pleasing environment. Unfortunately, many schools a fraction of Greenfield’s age provide dark, barren classrooms that devalue the teachers and students who use them. Much psychological research has explored the reaction of people to their environments, and in“the educational field this speaks clearly of everything from the development of self-worth to a reduction in vandalism and disciplinary problems. Cultural heritage. Although Greenfield’s emphasis on the western culture embodied in Greek and Roman classicism might be considered limiting today, the value of visual interpretations of cultural heritage cannot be overemphasized. Were Mrs. McClain selecting art for her school today, one would expect to find busts such as Tecumseh, Frederick Douglas, Susan B. Anthony, or Martin Luther King, and certainly paintings reflecting a variety of ethnic cultures. However, there is little doubt that quality paintings and sculptures permanently displayed and integrated with the curriculum add a valuable dimension well beyond student artwork tacked to bulletin boards. Academic excellence. An era that relies upon television screens and computer monitors for information and entertainment has difficulty envisioning the sense of individual and community pride generated by attending a musical or theatrical performance in the elegant McClain Hih School auditorium. Perhaps no question deserves more thoughtful consideration than, “How many modern schools have space to accommodate parents for a student recognition program anywhere except the gymnasium bleachers?” No matter how often we stress the importance of academics, many current educational facilities are dominated by their athletic amenities.

* * * * * *

Recently renovated with funding from the Ohio School Facilities Commission, Edward Lee McClain High School now boasts up-to-date technology, such as wiring for computers, while preserving the heritage that Greenfield treasures. Edward and Lulu McClain, Frank Harris, and William Ittner would be pleased.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 |

||