Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

Cleveland's New Stock Lawmakers and Progressive Reform by John D. Buenker |

|

During the highly productive progressive era of the early 1900's Ohioans enacted a myriad of reforms designed to cope with the serious political, economic, and social problems of the day. Included in their efforts was the updating of the state constitution more attuned to the complexities of twentieth century life. The contributions made to this record by such eminent reformers as Tom L. Johnson, Samuel "Golden Rule" Jones, Brand Whitlock, James M. Cox, and Judson Harmon have been discussed by a variety of scholars. These leaders, with few exceptions, came from families of long residence in the United States, were well-educated, of comfortable circumstances, and were influenced by the humanitarian and religious philosophies of traditional America; that is, they were in the category of the genteel reformers identified by such historians as Richard Hofstadter and George Mowry.1 A careful consideration of the era in Ohio also reveals that the reform impulse emanated from another, but far different source; namely, from the representatives of Cleveland's large recent immigrant population. Like many of their constituents, the Lake City's lawmakers were preponderantly either immigrants themselves or descended from fairly recent arrivals, were of other than English ancestry, professed religions which were largely unknown in colonial times, and came from working class environments. Yet, they made a highly significant contribution to the success of pro- gressive reform in the Buckeye State. NOTES ON PAGE 154 |

NEW

STOCK LAWMAKERS 117

To appreciate this phenomenon fully, it

is necessary to understand

what such distinguished scholars as

Arthur Link, Samuel Hays, and J.

Joseph Huthmacher have clearly

established--that there was not just one

"Progressive Movement" but

several simultaneous movements which

permeated all segments of society.2

The impersonal forces of industrializa-

tion, immigration, and urbanization had

intimately affected the lives of

every single individual in the United

States, and had profoundly altered

the traditional social, economic, and

political relationships. In order to

cope with the circumstances engendered

by their new environment

Americans in similar economic and social

situations combined into trade

associations, labor unions, farmer

cooperatives, civic associations, groups to

defend the Amercan way of life against

the incursions of immigrants, and

organizations to protect racial and

ethnic minorities against discrimina-

tion. Although their efforts were often

directed at the private sector, these

groups eventually turned their attention

to political action in the hope of

making common cause with the

representatives of other discontented

segments of society. With so many people

often working at cross purposes

to one another, any positive

accomplishments were the result of temporary

working coalitions on specific issues,

programs, or candidates. It was

precisely this discovery that politics

could be made relevant to curing the

major maladies of the period which

marked the beginning of the pro-

gressive era.

Human motivation, especially in

politics, is exceedingly complex and

difficult to evaluate. The old stock,

middle-class reformer saw himself as

entering politics primarily to effect

the realization of certain principles

which he derived from his religious and

cultural heritage. Historians have

also argued that he engaged in political

activity because he felt his once

privileged status in society was

threatened by the newly rich on one side

and the rising industrial working class

on the other.3 The urban, new

stock wage earner and his

representatives, on the other hand, usually had

in mind such concrete aims as a higher

wage, better working and living

conditions, a maximum impact for his

vote, and the defense of his cultural

heritage from nativist attack. The

wellspring of his action was first-hand

experience and he was usually prone to

seek specific remedies for indentifi-

able wrongs. At the same time, it is

possible to argue that the new stock

politician also saw himself acting in

defense of certain abstract principles--

the dignity of all men, political

equality, the ideal of a pluralistic society.

The instances of clashes over ideals and

interests between the old stock

middle class and the new stock working

class were numerous during the

progressive era, but so too were

incidents of their cooperation. Indeed

the success of progressive reform in

most of the major industrial states

usually depended upon it.4

In Ohio, as elsewhere, the progressive

era began in the cities. In Cleve-

land, the election of Tom L. Johnson as

mayor in 1901 heralded the begin-

ning of progress in that city which was

almost unequaled anywhere else

in the nation. During his four terms in

office, Johnson challenged the

118 OHIO HISTORY

street railway companies, fought for

municipal ownership of basic utilities,

thoroughly reorganized the city's

government, augmented its recreational

facilities, and reformed the penal and

legal system. By the time Johnson

left office in 1910, Cleveland was

thought to be a model city, acclaimed

even by such severe critics of urban

affairs as Lincoln Steffens. Johnson

himself was a fairly typical old stock,

middle-class reformer whose main

aim was to eliminate special privilege

of all kinds and to implement the

social theories of the single-taxer

Henry George. Most of his chief lieuten-

ants such as Newton D. Baker, Frederic

C. Howe, and Harris R. Cooley

came from similar social backgrounds,

and one of Johnson's major ac-

complishments was the arousing of the

reform impulse in the city's middle

class.5

To attribute the success of reform in

Cleveland solely to middle-class

dynamism, though, would be a serious

mistake because the population

of the city was so overwhelmingly new

stock in makeup. Nearly thirty-

five percent of Cleveland's population

in 1910 was composed of people of

foreign birth, while another forty

percent were but second-generation

Americans. Even though the census

figures do not trace ancestry beyond

this point, it is also highly likely

that a significant portion of the remain-

ing quarter of the population were

descendants of those who had emigrated

to the United States in the early stages

of the Industrial Revolution. Of

the nearly three-quarters who were of

foreign stock, 28.6 percent were of

German descent and another 18.4 percent

came from various portions

of the Austrian Empire. The remainder,

in order of percentage, came from

Hungary: 10.9; Russia: 9.4; Ireland:

8.6; England: 6.3; Canada: 4.3; Italy:

4.0; Scotland: 1.5; and Wales: 0.8.6 All

told, Cleveland was one the most

polyglot cities in the United States,

and it is difficult to see how any re-

form movement could have succeeded

without a broad appeal to these

various ethnic minorities.

That Johnson did receive much of his

reform mandate from the city's

recent immigrants is apparent both from

his programs and his voter support.

In his various campaigns Johnson

carefully cultivated the immigrant

strongholds on Cleveland's west side,

generally seeking to enlist the aid of

the local leaders rather than oppose

them. His three thousand vote plu-

rality in the new stock wards was

instrumental in his all-important first

victory in 1901, and his popularity in

these areas steadily grew during

his successive administrations. By

espousing such reforms as a three-cent

streetcar fare and public ownership of

utilities and by refusing to crack

down on saloons and gambling

establishments, Johnson clearly bid for the

support of the foreign stock voter and,

conversely, often incurred the wrath

of the city's middle class. According to

Fredric Howe, such issues as the

three-cent fare pitted "men of

property and influence" against "the

politicians, immigrants, workers, and

persons of small means," with him-

self and Johnson definitely favoring the

latter groups. "His program," a

perceptive analyst of Cleveland's

minority groups later wrote, "appealed

to the politically oppressed and to the

underprivileged, and from the

foreign wards came most of his

support."7

NEW

STOCK LAWMAKERS 119

Although terms like "boss" and

"machine" might seem inappropriate

to apply to a reformer of Johnson's

stature, it must be acknowledged that

he owed a great deal of his success,

both at the city and state level, to

the tightly disciplined organization

which he constructed, an organization

based upon the city's predominantly

foreign stock vote. Contemporary

newspapers often portrayed Johnson as a

political boss, a judgment in

which the mayor himself gladly

concurred. Two modern scholars of urban

affairs, Charles Glaab and Theodore

Brown, have described the Cleveland

mayor as a "reform boss" who

deliberately played for lower class votes and

pursued many policies more attuned to

their desires than to those of the

old stock middle class. This

interpretation is largely sustained by Hoyt

Landon Warner in his study of Ohio

progressivism. Acknowledging that

"many of Johnson's methods were

scarcely distinguishable from those of

his opponents," Warner asserts that

the reformer gained control of party

committees, dictated to the state

convention, drafted the platform, selected

the candidates and generally

"transformed the loyal Democracy of Cleve-

land and Cuyahoga County into a party in

his own image, dedicated to

social reform." Since so much of

Cleveland's "loyal Democracy" was com-

posed of the city's new stock voters,

office-holders and party functionaries,

it seems evident that their contribution

to Johnson's success has not been

fully appreciated. By the progressive

years, as we shall see, representatives

of these ethnic minorities had risen

through the party's ranks and had

come to dominate the city's delegation

in the General Assembly.8

Balked by the legal restrictions placed

upon city government in such

areas as taxation and regulation of

utilities by state law, the Cleveland

Democrats turned to state-wide politics

where they hoped to effect reforms

through cooperation with progressives

from other cities. Their original

aims were to reform Ohio's tax laws, to

make structural changes in the

state's electoral and apportionment

system, and to free the cities from the

direct control of the legislature. Later

they turned their attention to

labor and welfare questions, the

regulation of business, and a variety

of social questions. The high point of

the progressive era on the state

level in Ohio came during the

administrations of two Democratic governors,

Judson Harmon, from 1909 to 1913, and

James M. Cox, from 1913 to 1915.

In 1912, a state convention wrote

amendments to the constitution, which

made possible the passage of a myriad of

economic and political reforms

during the Cox administration. By 1915

Ohio ranked with a handful of

other states as the most progressive in

the nation.9

Without detracting in any way from the

primacy of leadership exercised

at the state level by such old stock,

middle-class reformers as governors

Harmon and Cox, mayors Tom Johnson,

Brand Whitlock and Newton

Baker, the Cincinnati politician Herbert

Bigelow and others, it is impor-

tant to note that many of Cleveland's

new stock lawmakers also showed

in this leadership function by serving

as committee chairmen, drafting and

introducing important legislation,

guiding it through the required pro-

cedures, and rounding up the necessary

votes. William A. Greenlund, a

120 OHIO HISTORY

second generation Danish-American who

was in the real estate business,

for example, was the sponsor of such

significant legislation as the Mothers'

Pension Act, the Liquor Licensing Act,

and the repeal of the Smith One

Per Cent Tax Law. In addition, he served

as chairman of two important

senate committees, and later presided

over that body as lieutenant-governor

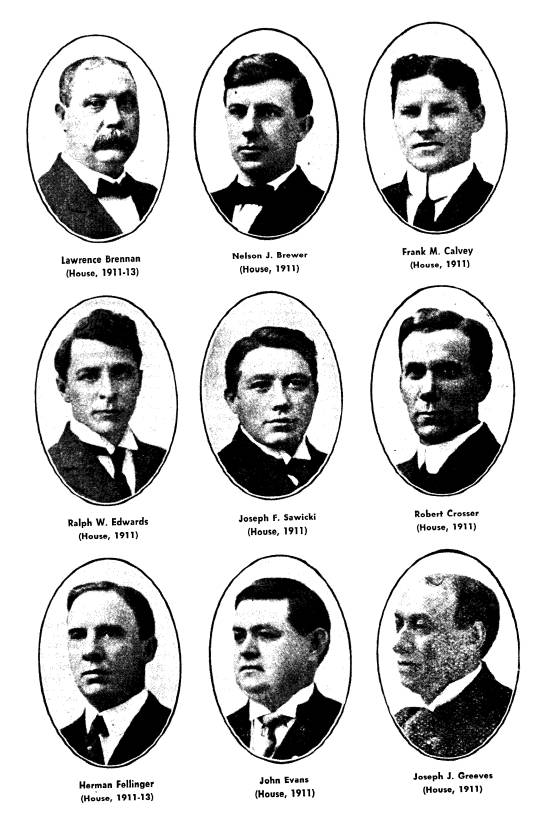

for much of the 1914 session. Lawrence Brennan,

a second generation

Irish Catholic, worked mostly behind the

scenes in 1913 but, according

to historian James Mercer, "his

influence was felt upon all the important

legislation of the session." Robert

Crosser, a Scottish immigrant, was the

author of the bill providing for

municipal initiative and referendum and

was rewarded for his service by being

picked to run for Congress in 1912,

where he represented Cleveland almost

continuously until 1955. He and

Carl D. Friebolin, a second generation

German-American, were disciples

of Johnson and, according to Warner,

"played a much more aggressive

role in proposing and guiding

legislation than their years of experience

seemed to warrant." In the 1913

session Friebolin advanced to the state

senate where he was chairman of the

judiciary committee and functioned

as Johnson's liaison man to that body.

Maurice Bernstein, the son of Jewish

immigrant parents from Poland,

served as chairman of the senate

privileges and elections committee in

1913 and was often entrusted with the

sponsorship of key legislation, in-

cluding the home rule tax bill and the

resolution to ratify the Seventeenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution.

James A. Reynolds, an English

immigrant and executive of a machinists'

union, was the author of a

number of labor and welfare measures and

also led the fight for such

political reforms as woman suffrage.

Another official of the machinists'

union, Harry F. Vollmer, a second

generation German-American, was

so zealous in his sponsorship of such

pro-labor proposals as a mandatory

eight-hour day that he occasionally ran

ahead of the wishes of the middle-

class leadership of his own party.

Herman Fellinger, born in Alsace-Lor-

raine chaired the insurance committee of

the lower house, introduced

several important regulatory laws, and

drafted a compromise amendment

which made possible the passage of a

women's hours bill in the 1913 ses-

sion, while the Scottish-born T. Alfred

Fleming authored five successful

measures during the second Cox

administration, 1917 - 1921. Two second-

generation Irish Catholics,

Representative John C. Smith and Senator

James S. Kennedy, were also productive

legislators in the 1917 session,

with Smith introducing three key

regulatory acts, and Kennedy, the

secretary-treasurer of the Plumbers'

Union Local in Cleveland aiding many

pro-labor measures through his position

as chairman of the senate labor

committee. The list could be extended,

but it is evident from this brief

enumeration that Cleveland's new stock

lawmakers often assumed posi-

tions of leadership.10

In addition, it has been acknowledged by

most students of Ohio pro-

gressivism that the Cuyahoga County

delegation turned in a good record

of support for the major reforms

introduced during the era, but it has

|

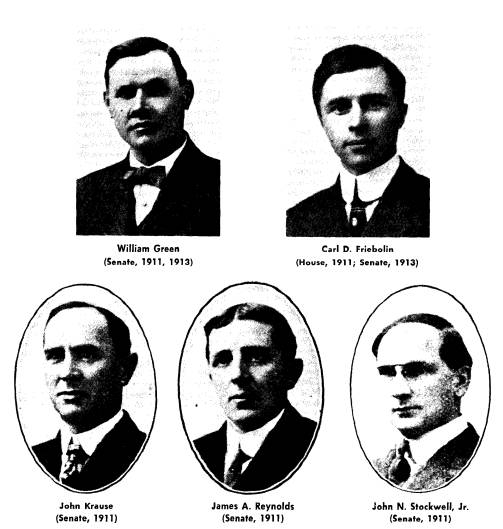

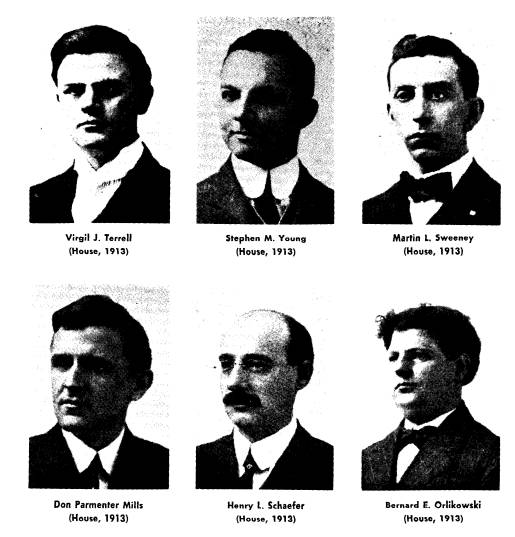

not been sufficiently recognized that the Cleveland contingent was heavily dominated by lawmakers of recent immigrant origins. Of the three senators who represented the county in 1911, only one, John N. Stockwell, Jr., was of old stock lineage. The other two were the English-born Reynolds and John Krause, a German-American druggist born in Cincinnati. Of the eight Democrats in the lower house only Nelson Brewer was descended from a family of long residence in the United States. Besides Fellinger, Crosser, Friebolin, and Brennan, Cuyahoga County was represented by the three immigrants--Joseph F. Sawicki, born in German Poland, a Roman Catholic, and an official of a number of Polish national societies; Joseph J. Greeves, a native Irishman and editor of a Catholic newspaper; and Ralph Wigmore Edwards, a native of Wales. Even the two Republican members from Cuyahoga County were of recent residence in America-- John Evans, a Welsh immigrant with a working class background and Frank M. Calvey, a second generation Irish-American.11 The same general pattern prevailed in 1913. The senators were, in the main, lawyers by profession and consisted of Bernstein, Greenlund. |

|

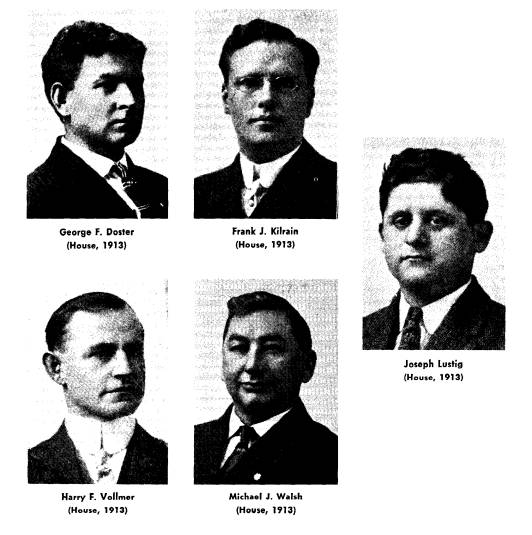

Friebolin, E. J. Hopple, native born, and Vincent Zmunt, the son of an Austrian immigrant and a Roman Catholic. The number of representa- tives had risen to thirteen under the new apportionment system and only two of these, Stephen M. Young and Don Parmenter Mills, could be con- sidered old stock Americans. Brennan and Fellinger were reelected and the remainder of their colleagues constituted a fairly good cross section of the city's ethnic minorities. Three were second generation German- Americans--George F. Doster, a member of the carpenters and joiners union, Vollmer, and Henry L. Schaefer. Four others were Irish Catholic-- Frank J. Kilrain, Martin L. Sweeney, Virgil J. Terrell, and Michael J. Walsh, a bridge builder and the former deputy sheriff of Cuyahoga County. Bernard E. Orlikowski, a paving contractor as well as in the wholesale grocery and liquor trade, was a Polish immigrant and a Roman Catholic, while Joseph Lustig was the son of Bohemian immigrant parents. Of the twenty-eight men who represented Cuyahoga County during the 1911- 1913 crucial period in the Progressive Era, eight were immigrants, thirteen were the sons of immigrants, and two were Irish-Catholics of older American origins, leaving only five who were descendants of traditional native American stock. The percentages were not quite so impressive from 1915 through 1919, but the Cleveland delegation continued to be dominated by representatives of the city's minority groups, most of whom were no more than second generation Americans.12 As might be expected from their origins, these new stock legislators were especially concerned about the enactment of labor and welfare measures. In these issues they found natural allies among the representa- tives of organized labor from other parts of the state, particularly from William Green of Coshocton, the future head of the American Federation of Labor. The son of English immigrant parents, Green had worked in the coal miners since boyhood and hence had much in common with many of the new stock Cuyahoga Democrats. During the 1911 and 1913 sessions he was one of the most effective members of the senate, drafting and guiding a number of bills designed to better the lot of working men in general and coal miners in particular. Occasionally Green even branched into other legislative areas, introducing the measure to call the momentous |

|

124 OHIO HISTORY constitutional convention in 1911, and was rewarded for his effectiveness by being elected president pro tempore of the upper chamber in 1913. On most labor and welfare issues the forces of organized labor and their Cuya- hoga allies could count upon the support of the old stock, middle-class pro- gressives, especially if the measure in question were aimed at protecting the defenseless, such as women and children. When the more ardent of the pro-labor lawmakers such as Green, Vollmer, or Reynolds sponsored measures to aid able-bodied male workers, though, the middle-class re- formers like Johnson and Cox sometimes fought this legislation as a form of special privilege.13 On the whole, however, the impressive array of labor and welfare laws enacted in Ohio during the progressive years was the result of effective cooperation between the middle-class reformers, the leaders of organized labor, and the representatives of the state's urban, |

|

NEW STOCK LAWMAKERS 125 new stock wage earners, with the Cuyahoga delegation clearly in the forefront. The so-called Mothers' Pension Law, for instance, considered one of the major achievements of the period in this area, was drafted by Senator William Greenlund in the 1913 session. This measure represented a comprehensive attempt to reorganize the state's welfare program for indi- gent mothers with dependent children. Besides providing for pensions, the law also regulated the conditions of child labor and stipulated com- pulsory education until the age of fifteen for boys and sixteen for girls, and was known as the "Magna Carta of the children of Ohio." As such it had the unanimous backing of the entire Cleveland delegation in both houses of the General Assembly. When the Republican administration in 1915 tried to weaken the intent of the measure by allowing county sheriffs |

126 OHIO HISTORY

to investigate welfare recipients, the

Cuyahoga lawmakers abstained from

voting in this instance.14

Another cardinal achievement of

progressivism in Ohio, the compulsory

workmen's compensation law, received

strong backing from Cleveland's dele-

gates. The original bill in 1911 was

introduced by William Green and pro-

vided for the creation of a state

insurance fund financed primarily out of

employer contributions. It stipulated an

automatic payment to the worker

without the necessity of proving

negligence and also created a State Liability

Board of Awards. The measure passed both

houses over the rather token

opposition of some rural Republicans and

with the unanimous support of

Cleveland lawmakers. In 1913 Green

received the backing of the Cuyahoga

delegation for his amendment which made

workmen's compensation com-

pulsory, although it allowed some

employers to provide for self insurance

outside the state system. When the

Republican superintendent of insurance

Frank Taggart ruled that the private

liability companies could cover self-

insurers, the State Federation of Labor

sponsored a measure, via an initia-

tive petition, to prohibit this

activity, and the Cuyahoga lawmakers voted

almost unanimously for it in the 1917

session.15

The regulation of working hours,

especially for women, found similar

favor with the Lake City lawmakers. Once

again it was William Green who

in 1911 introduced the original bill

that provided for a nine-hour day and

a fifty-four hour week. Opposition to

the measure in the house, however, in-

spired Herman Fellinger to amend the

proposal to a ten-hour day and a

sixty-hour week over the objections of

all of his colleagues, but on the final

vote the entire Cleveland group

concurred. In 1913, Vollmer sought to lower

the limit to eight hours and to include

women working in hotels and mer-

cantile establishments as well as

factories. Under threat of a veto by Gover-

nor James Cox, Vollmer and his

associates finally agreed to a nine-hour day

and certain other limitations, but not

before they had demonstrated their

desire for the strongest possible law.

As further evidence of their concern

for shorter working hours for women, the

Cuyahoga delegation approved a

further extension of the law's provision

in 1917 when it was introduced by

Tom Reynolds, an Irish Catholic labor

leader and representative from Cleve-

land. Although the issue of maximum

hours for male workers did not en-

gender much interest in the legislature,

with the exception of Walsh, the

Cuyahoga delegates in attendance did

back a bill drafted in 1913 by Percy

Tetlow of Columbiana County to provide

for an eight-hour day for public

employees as an example for private

industry.16

In a similar vein, Cleveland lawmakers

were in the vanguard of those who

sought to establish a strong industrial

code for Ohio and to provide for a

statewide commission to oversee it. They

were unanimous in their support of

a measure drawn up by Senator James

Reynolds in 1911 to require that em-

ployers report any serious accident

which resulted in more than two days

absence to the Chief Inspector of

Workshops and Factories. In the following

session, their backing was accorded to

Vollmer's proposal to provide a fine of

from twenty-five to one hundred dollars

for any violation of the statutes re-

NEW STOCK LAWMAKERS 127

garding abuses in sweat shops, as well

as to Friebolin's bill requiring that

any business employing more than five

people must report the number,

wages, hours and conditions of labor of

any females or workers under

eighteen years of age. To oversee these

laws Senator William Haas of Dela-

ware proposed the creation of a state

industrial commission which would

assume the powers of all the existing labor

boards and bureaus, as well as

have the general duty to regulate hours

and conditions of labor in the in-

terest of the employee. Although some

labor leaders reportedly feared that

the board would exercise too much

control, it eventually received the com-

plete support of the Cleveland

delegation as well as that of all the other

labor-oriented legislators. During the

same session the Cuyahoga lawmakers

upheld an amendment to the Haas bill by

Green stipulating that the newly

established commission would accede to

all the powers of the State Board

of Awards.17

The wages of Ohio's industrial workers

were also a matter of concern for

the state's new stock legislators. The

constitutional convention of 1912

recommended the enactment of a minimum

wage law, but Governor Cox

urged careful study of the proposal and

recommended its limitation to wom-

en and children. In the end he prevailed

upon the lawmakers to refer the

matter to the industrial commission for

study. Although Ohio did not enact

a minimum wage law, as such, in this

period, her labor-oriented lawmakers

did endeavor to protect workers'

earnings in other ways. In 1913, the Cleve-

land delegation backed a law which

required the semi-monthly payment of

wages and were successful in frustrating

the attempts of conservatives to

riddle it with exceptions. Two years

earlier they had generally agreed to the

licensing and regulation of wage loan

corporations which were useful in

helping the worker to borrow money in

emergencies. All but two of their

number, who did not vote, also supported

a 1915 bill to further strengthen

the law's provisions.18

Among other disadvantaged groups singled

out for special consideration

by the General Assembly were the state's

public school teachers, and Cleve-

land's urban new stock lawmakers were

also clearly sympathetic to the re-

form efforts. John Krause introduced a

bill providing for retirement pen-

sions for teachers in 1911. The measure

passed the senate by a 23-3 count in

which Green joined the opposition and

Stockwell was absent but most other

Democrats voted in favor. In the lower

house all the Cleveland lawmakers

present lent their support to passage,

Joseph Greeves and Frank Calvey did

not vote. Similarly, in the 1914 special

session, eleven of the thirteen Cuya-

hoga representatives in the lower house

voted for the establishment of a forty

dollars a month minimum wage for

teachers, with the state to make up the

difference if the local school district

was unable to do so. Three of the five

Twenty-fifth District senators,

Friebolin, Greenlund, and Bernstein, either

abstained or were absent, but the rest

of their colleagues voted for passage.19

Cleveland's new stock politicians were

likewise agreeable to the efforts of

Green and other labor leaders like Percy

Tetlow and John J. Shanley of

Portage County to better the condition

of the state's sizeable number of coal

128 OHIO HISTORY

miners. Chief among the proposals was

one by Green which would have the

workers paid on a "run of the

mine" basis rather than by the amount of coal

weighed after screening. After failing

to obtain majority support in 1911,

the former miner reluctantly agreed to

Governor Cox's suggestion that a

commission be appointed to study the

matter in 1913. The following year

Green successfully guided his measure

through both houses of the legisla-

ture, aided considerably by the

unanimous support of the Cleveland delega-

tion. The latter also backed Green's

bills providing for the use of acetylene

gas in mines and for the stationing of

rescue cars in each shaft. Other mining

regulatory laws which merited their

concurrence included the prohibition

of "solid shooting," the

requirement that all men be cleared out of the mine

before blasting, the right of any next

of kin to sue mine owners in the event

of wrongful death, and the mandatory

enclosing of all mine shafts.20

If anything, Cleveland's legislators

were even more interested in the wel-

fare of Ohio's railroad workers than in

the state's miners. Except for Don P.

Mills, Stephen M. Young, Terrell, and

Walsh, who did not vote, they all

backed Vollmer's bill to provide for

eight hours rest after fifteen hours

work. In the same session all but

Fellinger, who was absent, voted in favor

of Doster's measure to require the use

of air brakes on eighty-five percent of

all railroad cars. On two separate

occasions during the period, they gave sub-

stantial support to full train crew

bills sponsored by lawmakers with railroad

union approval. In 1917 John C. Smith, a

son of an Irish-Catholic father

from Cleveland, introduced a bill

requiring seats for railroad employees.

This passed with the support of his

colleagues that were present. In addition,

everyone but the absent Virgil Terrell,

Norman R. Bliss, Walsh, and Tom

Reynolds voted in favor of a bill

providing for the appointment of a state

inspector of brakes and couplings.21

The list of labor and welfare measures

proposed and/or supported by

Cleveland's new stock lawmakers during

the height of the progressive era

could be extended almost indefinitely.

Only four of their number abstained

on a bill to regulate private employment

agencies. Frank J. Kilrain, another

Irish-Catholic descendant from

Cleveland, introduced a bill to prevent occu-

pational diseases among workers in

plants producing noxious fumes with

special reference to lead poisoning, and

it was endorsed by all but two of his

fellows, who were non-voting. Only two

of their number, who were absent,

failed to support a bill proposed by

James R. Clark, an Irish-American from

Cincinnati, to prohibit the use of

prisoners as contract labor.22 All in all,

it would be hard to single out any other

group in the legislature during the

period which sustained labor and welfare

measures with a greater degree of

consistency than did the new stock

Cleveland delegation.

Nor did the involvement of Cleveland's

new stock lawmakers in Ohio

progressive reform end with their

activities in the field of welfare legisla-

tion. They also made significant

contributions in the vital area of business

regulation. With certain persons holding

reservations, the Cleveland delega-

tion largely gave its support to the

creation of a state Public Utilities Com-

mission. The primary objection in 1911,

according to Warner, was to the

NEW STOCK LAWMAKERS 129

failure of the bill to ensure sufficient

protection of the home-rule principle,

which allowed major cities to regulate

their own utilities, since the power to

grant new franchises would be in the

hands of the commission-not the in-

dividual city. In addition, John

Stockwell and some of his colleagues wanted

rates to be based on physical valuation

of property, rather than on capitaliza-

tion, as the measure originally

stipulated. Balked on both these points, the

Cuyahoga delegation split in the final

vote, with Stockwell and five repre-

sentatives voting against the bill. In

the final vote the re-amended house

bill passed twenty-two to eight, all

three of the senators from Cuyahoga

County voting nay.23

Events in ensuing sessions of the

legislature, however, amply demon-

strated that the reluctance of some

Cleveland lawmakers to vote for the

Public Utilities Act of 1911 was due to

concern for home rule and not to

any aversion to the principle of

regulation. In 1913, Don Mills sponsored

legislation to increase the latitude of

municipalities in dealing with public

utilites which was strongly supported by

his fellow Democrats over the ob-

jections of many Republicans.

When Mills added a series of amendments

designed to clarify the powers

and duties of the new commission in the

special session of 1914, the entire

Cleveland delegation, except for

Greenlund who had moved up to the post

of lieutenant-governor, voted in the

affirmative. In 1915, the Republicans

sought to weaken the home rule principle

by permitting municipal councils

to request the state Public Utilities

Commission to review rates and prop-

erty valuations, and the Cuyahoga

lawmakers generally refused to concur.

In the senate three voted nay while the

other two abstained, and in the

house seven Cleveland representatives

opposed and three others abstained.

Norman R. Bliss received the backing of

all but three of his fellow Cleve-

landers for his bill which brought the

railroads under the supervision of

the Public Utilities Commission in

1917.24

The Cuyahoga lawmakers were consistent

in their support of home rule

with regard to efforts to curb the

influence of private traction companies in

the state's municipalities. One of the

hardest fought battles of the progressive

era in Ohio resulted when attempts were

made to repeal the so-called Rogers

Law of 1896 which permitted cities to

grant fifty-year franchises to street-

railway companies. Although the bill

introduced dealt with the franchise in

Cincinnati and legislators from that

city provided the leadership, the Cleve-

land lawmakers lent considerable

support. In fact, they were unanimous in

their backing of the strongest possible

measure introduced by Herbert S.

Bigelow of Hamilton County in 1913 which

passed the lower house by a

69-42 margin. When the opposition of the

traction companies forced the

introduction of a compromise bill by

Thornton R. Snyder of Hamilton

County later in the same session, two

Cleveland senators and two representa-

tives did not vote, while the remainder

accepted the substitute.25

The regulatory principle was also

involved in the adoption of a Blue Sky

Law, which regulated the sale of bonds,

stocks, and other securities, and of

real estate not located in Ohio. The

measure was introduced by James R.

130 OHIO HISTORY

Clark of Cincinnati in the lower chamber

and sponsored in the senate by

William Green. The bill passed the house

by a 107-0 vote, supported by the

entire Cincinnati and Cleveland

delegations. Two Republicans voted against

passage in the senate, but the measure

received the votes of all the upper

chamber Democrats, with the exception of

Carl Friebolin who did not

vote. Four years later, in 1917, the Cleveland

lawmakers in both houses

backed the creation of the office of

Commissioner of Securities who, in addi-

tion to having absolute authority in

issuing and regulating licenses of con-

cerns selling securities within the

state, was to regulate and license the loan-

ing of money, without security, upon

personal property, and of purchasing

or making loans upon salaries.26

In addition to these better known

ventures into the area of business regu-

lation, Cleveland's new stock lawmakers

were instrumental in several other

similar attempts. The regulation of the

insurance business, for example,

was the peculiar province of Herman

Fellinger, himself an official of the

German National Alliance Insurance

Company. Among other things, Fell-

inger sponsored bills to supervise

insurance companies other than life, to

regulate fire insurance companies and

their agents doing business in the

state, and to create a state

superintendent of insurance. In the main all these

bills were supported by his fellow

Cleveland Democrats. Fellinger also in-

troduced a truth-in-advertising measure

in 1913 which had their unanimous

backing. Regulation on various aspects

of banking likewise came at the be-

hest of such young lawmakers as William

Green and James Kennedy, and

had the complete concurrence of the

Cuyahoga delegation in the senate

and all but two in the house. Kennedy

also received the nearly universal

support of Cleveland's Democrats for the

creation of a state inspector of

building and loan associations. Similar

fealty was enjoyed by proposals

for establishing a Bureau of Markets and

a State Superintendent of Public

Works.27

If anything, the attitude of the

Cleveland Democrats in the 1911 General

Assembly toward the vital question of

taxation was even more forward-

looking than the view of many

contemporaries, given the special nature

of the problems faced by urban,

industrial America. They were particularly

concerned that the burden of taxes be

apportioned according to the ability

to pay. Consequently they were unanimous

in their support for the

ratification of the graduated federal

income tax amendment in 1911, as

well as for the adoption of a statewide

progressive inheritance tax in 1919.

In the latter case, the Cleveland

delegation was also in the vanguard of

those who opposed conservative efforts

to raise the minimum amount of

inheritance subject to the tax.28 But

the Cuyahoga lawmakers also had

another interest in tax reform, as

Warner very astutely observes. Since

they were representatives of a large

metropolis with many pressing and

expensive needs, they were especially

anxious to resist any restrictions on

the ability of the city to raise the revenue

necessary to provide necessary

social service to the urban populace. As

a result, they favored special home

rule provisions for taxation, and fought

against tax rate limitations on

NEW STOCK LAWMAKERS

131

municipalities. In 1911, for example,

some Cleveland lawmakers in the

lower house led the fight against a

provision in the Smith One Per Cent

Tax Law which placed an aggregate limit

of ten mills on taxable property

(five mills for municipal corporations).

Eventually, however, everyone

but Crosser, Evans, and Brewer, who did

not vote, acquiesced in the final

passage of the bill. Although Senator Greenlund

introduced a measure in

1913 to increase the amount of levy

possible, which was endorsed by the

mayors of the state's largest cities,

the bill was kept in committee and

the limitations remained on the books.29

Nevertheless, the Cleveland representatives

continued to press for tax

reform, and particularly for the type of

adjustments best suited to an

urban, industrial society. A Bernstein

proposal to introduce the home-

rule principle in taxation passed the

senate in 1913, but did not come

to a vote in the house. Another bill in

the same session which would have

made municipal bonds tax exempt and thus

encouraged investment in

city projects passed the legislature but

failed in a referendum vote, largely

due to rural opposition. Six years later,

the Cleveland lawmakers supported

a joint resolution providing for the

classification of property for the pur-

pose of taxation, and again took the

lead in successfully resisting an amend-

ment which would have placed limitations

on the amount of the levy.30

The biggest taxation issue of the era,

however, was the establishment

of a state tax commission in 1913, and

the Cleveland Democrats were

again on the positive side. Previously,

the evaluation of property had

been in the hands of local assessors, thus

making for a wide variation

throughout the state. The Cox

administration backed a measure introduced

by Milton Warnes, the house Democratic

whip, to create a state tax com-

mission to insure uniform levies. The

Republicans and some rural

Democrats fought the proposal

vigorously, but in the end it prevailed,

24-8 in the senate, and 73-42 in the

house. In both chambers the Cleve-

land contingent provided a solid phalanx

of support, along with most

other urban lawmakers. The Republican

administration of Governor Frank

Willis failed in an attempt to repeal

the Warnes Law in 1915, but the

State Supreme Court found it to be

unconstitutional in 1917, thus return-

ing authority to the local assessors and

weakening the efforts of reformers

to raise the revenue needed to operate a

modern state. The Cuyahoga law-

makers continued to support the cause of

better methods of taxation and

were unanimous in their favor of the

creation of a joint tax commission

to study the state's problems in 1917.31

As the Warnes tax commission bill

effectively illustrates, the develop-

ment of an efficient system of

administration was a cardinal aim of Ohio

reformers in the pre-World War I years.

Much of this activity doubtless

sprang from the oft-expressed desire of

the old stock, middle-class pro-

gressive for honest, proficient and

economical government, but the fact

remains that Cleveland's new stock

lawmakers were among the strongest

supporters of these changes. Chief among

the reorganization efforts was

the setting up in 1911 of one

centralized board of administration for the

132 OHIO HISTORY

state's penal institutions, charity

hospitals, schools and homes which assumed

the functions of many separate governing

boards. The bill passed the senate

on a nearly partisan 20-14 count, with

the majority Democrats prevailing.

In the lower house, where the vote was

70-38, only the Republicans, John

Evans and F. M. Calvey, marred the

perfect record of support for the

measure on the part of Cleveland's lawmakers.32

The establishment of a streamlined board

of clemency in 1917 marked

a similar victory for the idea of

improved method of handling requests

from prisoners. Introduced by John J.

Kilbane, the bill was endorsed by

his fellow Clevelanders and passed over

heavy Republican opposition. A

state board of rapid transit was the

brainchild of Harry L. Federman, a

second generation German-American from

Cincinnati. The 1917 bill was

backed by all of Cleveland's senators

and three-fourths of her voting rep-

resentatives. Another Cincinnatian,

Democrat Robert Black, proposed the

establishing of a legislature reference

department and received the complete

backing of the Cleveland and Cincinnati

delegations. All but three

Cuyahoga representatives--non-voting Mills,

Terrell, and Walsh--voted for

the introduction of a state budget

system in 1913, and nearly all of them

endorsed the various efforts of Carl

Friebolin to reorganize the state court

system. Even on the highly explosive

liquor question, the Cuyahoga

Democrats endorsed a centralized

approach, backing the proposal of Wil-

liam Greenlund for the establishment of

a state liquor licensing board.

Indeed, about the only measure designed

for more centralized administra-

tion which encountered the active

opposition of the Cleveland lawmakers

was the Republican sponsored bill to

establish a state agricultural board.

Motivated either out of urban prejudice

or in retaliation against rural

intransigence on matters of interest to

the cities, all five Cleveland senators

and six of her representatives refused

to concur, with four not voting, out

of a total of thirteen.33

In addition, the Cleveland Democrats

were extremely sympathetic to

the myriad of political reforms which

comprised much of the solid achieve-

ments of Ohio progressivism. It is

generally asserted that one of the key

desires of progressive reformers was to

give the people a more influential

voice in government; that is, to purify

and extend the ideal of democ-

racy.34 Based upon their

performance, the new stock lawmakers from Cleve-

land seemed to share this conviction,

but it is probable that their adherence

was reenforced by a very practical

political consideration. As representa-

tives of the state's most populous city,

they naturally favored any measure

which would place a premium upon the

mass vote. The more democratic

the political system became the greater

the chance would be that candidates

sympathetic to the urban point of view

could be elected and that laws

relating to the unique problems of the

cities could be enacted. Whether

they were primarily motivated by the

ideal or the practical is a moot

question, because both led ultimately to

the same goals.

The desire of urban areas to take the

selection of United States Senators

out of the hands of the often

malapportioned state legislatures and elect

NEW STOCK LAWMAKERS 133

them by popular vote, led the Cleveland

delegates to support the ratifica-

tion of the Seventeenth Amendment to the

Federal Constitution. In a

statewide election, the influence of

urban voters would be clearly greater

than it was in the legislature.

Consequently the entire senatorial delega-

tion and seven of the ten

representatives voted for the adoption of the

so-called Oregon Plan in 1911, while the

other three merely abstained. This

plan called for a binding pledge on the

part of the legislator to vote for

the Senatorial candidate who carried his

district. The introduction of the

Federal amendment rendered this approach

obsolete, however, by permit-

ting direct popular vote. The

ratification resolutions were entrusted to

Zmunt, Bernstein, and Robert Black of

Cincinnati and carried both houses

easily, with all five Cleveland senators

and twelve of the thirteen rep-

resentatives voting to ratify.35

Their support for the woman suffrage

amendment was not quite so

overwhelming but it did eventually

develop. The antipathy to female vot-

ing among recent immigrant groups was

regularly voiced by the foreign

language newspapers and by various

religious organizations, notably the

Catholic Church, and this antagonism

naturally reflected itself in the

attitude of Cleveland lawmakers. Some

Cuyahoga legislators, especially

James Reynolds, however, were consistent

advocates of the reform and

eventually nearly all their cohorts came

to see the advantage in adding

large numbers of new stock females to

the voting lists. As late as 1917,

though, five Cleveland representatives

and two senators voted against

Reynold's bill to allow woman suffrage

for presidential elections, and even

in 1919 Senator Charles Wagner and six

representatives refused to agree

to a petition requesting the state's

congressmen and senators to support

the proposed amendment to the Federal

Constitution. When the amend-

ment was finally considered by the

General Assembly, however, only one

of the city's legislators, Joseph S.

Backowski, voted in the negative while

three others abstained.36

Initiative and referendum in municipal

elections also owed much of

its success to the efforts of

Cleveland's new stock legislators. Here was

another innovation which would enable

the city voter to amplify his

influence. It was Robert Crosser of

Cleveland who introduced the enabl-

ing legislation in the 1911 session. The

opponents of the measure sought

to weaken it by requiring the signatures

of thirty percent of the registered

voters on any petition, but the

Cleveland Democrats in both chambers

nevertheless granted the bill their full

support. In 1913 they followed

through on their intent by supporting a

measure to provide for municipal

initiative and referendum upon the

petition of ten percent of the electorate.

In addition, the Cleveland delegation

largely voted in favor of most ef-

forts to protect the petitions against

possible abuses such as forgery and

fraud, particularly when it was revealed

that the conservative Equity As-

sociation had sought to use the new

method to eradicate the workmen's

compensation system and various tax

reforms. Recall of officials, another

popular direct government idea of the

era, failed of adoption, but did

134 OHIO HISTORY

receive considerable support from the Cuyahoga lawmakers. Friebolin

introduced a recall proposal in 1911,

and all five senators voted for the bill

which passed the upper house in 1913.37

In the same vein, most of the Cleveland

contingent lent its backing

to the direct primary law passed in

1913. This is particularly noteworthy

inasmuch as the direct primary is

singled out by historian George Mowry

as a reform which "left the usual

immigrant from southern and central

Europe distinctly cold." Even so,

the measure pased the lower house on

an 80-20 vote, over the objections of

several rural legislators. Kilrain and

Vollmer abstained, but the remainder of

their fellows voted for passage

including Doster, Fellinger, Lustig,

Orlikowski, and Schaefer, all of recent

Central European derivation and

representing districts with large con-

stituencies of similar ethnic origins.

In the senate, where only Friebolin's

absence spoiled a perfect affirmative

record for the Cleveland delegation,

the bill triumphed by a 23-3 margin.38

Even the highly successful

constitutional convention of 1912 owed a

great deal of its impetus to urban,

working class liberalism. The resolution

calling for the selection of delegates

on a non-partisan basis was introduced

in the senate in 1911 by William Green.

It passed the upper chamber

by a decisive 27-1 vote, with all three

Cleveland solons concurring. The

vote in the lower house was 74-24 and it

reflected the special desire of the

state's cities for a more modern

charter. The entire Cleveland contingent

and all but one Cincinnati lawmaker

voted in favor, joined by the rep-

resentatives of Toledo, Dayton,

Columbus, and the other largest cities.

The resultant constitutional changes

updated the state's government by

adopting a series of specific amendments

which were later implemented

by the legislature, such as initiative

and referendum, woman suffrage,

municipal home rule, tax reform, direct

primary, judicial reform, and

benefits for labor.39

Perhaps most surprisingly of all,

Cleveland's primarily new stock law-

makers proved themselves to be

supporters of so-called good government

legislation. This type of reform was

considered the special province of the

upper-middle-class progressive who often

regarded honest government as

a panacea for all social ills. Generally

speaking, the urban working class

politician put more emphasis on the

positive role which government

should play in the social order and was

often willing to allow a little

graft and favoritism now and then if it

helped to lubricate the machinery.

He was often inclined to dismiss the

reformer with such derisive sobriquets

as "goo-goos."40 Within

limits, however, the Cleveland lawmakers regard-

less of what might have been assumed

from their origins, granted much

backing to good government.

Their attitude toward misconduct in the

legislature, for example, was

generally progressive, although it

varied in direct proportion to the

identity of the persons involved. The

entire Cuyahoga delegation in both

houses voted in favor of the lobbyist

registration act of 1913, requiring

special pleaders to work in the open.

The senatorial contingent was also

NEW STOCK LAWMAKERS

135

unanimous in its support of a bill

making it a crime to bribe a legislator.

When charges of soliciting bribes were

levied against several senators in

the 1911 session, the Cuyahoga

representatives supported vigorous prosecu-

tion of the accused, and Krause and

William Green even refused to serve

on a committee which was generally

regarded as being packed so as to pro-

duce a "whitewash." On the

other hand, when one of their own people,

Frank G. Delehanty, was under suspicion

of accepting a bribe in 1919, his

colleagues were less interested in

vigorous prosecution. On the joint resolu-

tion calling for an investigation of the

charges, four of the thirteen Cleve-

land representatives and two of the four

senators abstained.41

By the same token, Cleveland lawmakers

demonstrated a general interest

in preventing abuses in the electoral

process. The legislators were in sub-

stantial agreement with the corrupt

practices act of 1911 which sought

to place controls on campaign

expenditures and prohibit coercion of

voters. Because the city's three

senators desired a somewhat stronger law,

however, they abstained on the final

vote. In the same session, the three

senators and six of the ten

representatives voted in favor of a stronger

voter registration law. In the 1913

meeting of the General Assembly, the

Cuyahoga delegation gave nearly solid

backing, three not voting, to several

bills introduced by Bernstein and

Fellinger to guarantee an honest count

of the ballots by requiring that they be

kept for a specified length of time

in sealed envelopes and that the returns

be handed over promptly to the

county board of election or to the secretary

of state. Two years later, all

but one senator and three

representatives voted for a bill introduced by

Norman Bliss of Cleveland which provided

for a fine for circulating false

rumors about candidates. In 1917, all

but two members of the lower house

favored a joint resolution proposed by

Charles Mooney of Cleveland to

create an electoral commission to

investigate and suggest revisions in the

state's electoral laws. Only on the

issues of filing election expenditures

and investigating the election of 1916

did they show any possible reserva-

tion, and even here it was expressed by

the abstention of three senators

rather than open opposition.42

What concerned the Cuyahoga delegates

even more than electoral purity,

however, was the guarantee of the

greatest possible participation in the

political process by the urban, new

stock, working class voter upon whom

they relied. Consequently, they

supported a bill introduced by floor leader

Lawrence Brennan which made a portion of

election day a legal holiday,

thus enabling a greater number of wage

earners to reach the polls. Bren-

nan's measure to insure longer poll

hours also received support from his

fellow Clevelanders. There was a little

more division of opinion on the

question of protecting employee rights

from employer coercion, but most

of it was over details rather than

principle. Bernstein's bill to forbid

employers to accompany workers to the

polls received the unanimous

backing of his fellow Cleveland

senators, but only that of two of the

city's representatives, labor leaders

Terrell and Vollmer. In 1917, however,

all of the twelve assemblymen voted for

a similar bill.43 In the long run,

136 OHIO HISTORY

the fortunes of Cleveland's Democrats

were best secured by guaranteeing

the freest possible elections since

their stand an economic and social ques-

tions assured them of the mass vote, and

this circumstance established their

position on most matters pertaining to

the electorate.

New stock lawmakers also played a

prominent role in the adoption of a

civil service system in Ohio. It was

Friebolin who introduced the state-

wide civil service bill in 1913. He and

three senatorial colleagues voted

for the measure on fina1 passage, but

four Clevelanders in the lower

house--Doster, Lustig, Schaefer and

Vollmer--abstained. According to

Warner, the bill did meet some

opposition from labor leaders such as

William Green, and the opposition of

three of the four labor-oriented

representatives probably emanated from

mutually held sentiments. The

thirty-two votes cast against the

measure in the lower house in 1913, how-

ever, were mostly rural Democrats and

Republicans; while all but two

Cleveland Democrats voted against the

opposition party's attempts to alter

the system in 1915, the bill, nevertheless,

passed.44

Taken as a whole, then, the attitude

assumed by Cleveland's predominant-

ly "new stock" legislators on

economic and political issues during the period

was consistent with the aims of

progressive reform. The same could not

be said about their attitudes toward

measures designed to effect the moral

regeneration of society. As Hofstadter

and Mowry have correctly observed,

many of the old stock, middle-class

reformers considered the latter to be

as crucial to the success of their

programs as economic or political change.

Inasmuch as they traced much of the

reason for the alleged moral decay

of America to the pernicious influence

of the recent immigrant and there-

fore aimed their remedies largely in

that direction, it was only natural

that the representatives of the new

stock citizenry should take the lead

in resisting the "moral"

reformers. When concern for the Sabbath on the

part of old stock, Protestant Ohioans

led to the proscription of Sunday

baseball, Cleveland and Cincinnati delegations,

instead, led the success-

ful fight for its legalization.45

Doubtless the influence of the professional

baseball clubs in the two ciites

somewhat dictated their stand, but so

too did the belief of their constituents

in a Continental Sunday, in which

recreation was not considered in

conflict with worship.

This cultural gulf between the new stock

lawmakers and the old stock

reformers was especially evident on the

issue of the prohibition of

alcoholic beverages. For the native,

Protestant American, as represented

by the Anti-Saloon League and the

Woman's Christian Temperance Union,

prohibition increasingly became the

keystone for the moral regeneration

of the nation, and especially of the

recent immigrant; but for the latter the

issue became the symbol of narrow-minded

intolerance, and his representa-

tives resisted it ferociously. As

previously noted, it was W. A. Greenlund

who introduced the 1913 law which

provided for a statewide liquor li-

censing system. This innovation was clearly

against the wishes of the power-

ful dry forces, but it might have proven

a workable solution to the drink-

ing problem. When the Republicans

overturned the law in 1915 and forced

NEW

STOCK LAWMAKERS 137

a return to the local control of

licensing, the Cleveland delegation formed

a solid bloc of opposition. Together,

the Cincinnati and Cuyahoga law

makers constituted about sixty percent

of the votes cast against the

Eighteenth Amendment. Even after

prohibition became the law of the

land, several Cleveland legislators

still refused to vote in favor of the

statutes designed to enforce it.46 Contemporary

opinion had no doubt

which was the progressive side of the

issue, and the opponents of prohibi-

tion were branded as hopeless

reactionaries and tools of the liquor interests.

Within a decade, however, repeal of the

ill-starred social experiment be-

came one of the cardinal tenets of

liberalism. In this context, it would

be difficult to fault Cleveland's new

stock Democrats for their stand on

prohibition and Sunday blue laws.47

Regardless of the merits of the

prohibition controversy, it is clear that

Cleveland's new stock legislators were a

vital element in the success of

progressive reform in Ohio. Their

leaders helped to draft, sponsor and

guide some of the key legislation of the

period, and their votes formed

a solid base upon which to build support

for most progressive measures.

On some labor and welfare questions, the

Cuyahoga lawmakers actually

took positions in favor of stronger laws

than those desired by old stock,

middle-class leaders of their party. On

most other issues these two groups

were able to engage in highly productive

collaboration. If their refusal

to accept measures aimed at moral

regeneration such as prohibition some-

times put Cleveland's representatives at

odds with the native reformer,

the course of events often proved the

wisdom of their stand. By assuming

their generally forward-looking

attitudes, these new stock lawmakers were

providing themselves and their

constituents with the concomitants neces-

sary to survive and prosper in the harsh

reality of urban, industrial America,

and were operating in the same context

as their counterparts in such other

great cities as New York, Chicago,

Boston, Jersey City, and San Francisco.48

Like them, also, Cuyahoga's legislators

were helping to hasten the day

when the nation's ethnic and religious

minorities would achieve the fulfill-

ment of their dream of equality.

THE AUTHOR: John D. Buenker is an

assistant professor in the history

depart-

ment at Eastern Illinois University.