Ohio History Journal

WILLIAM BARLOW AND DAVID 0. POWELL

Homeopathy and Sexual Equality:

The Controversy Over Coeducation

at Cincinnati's Pulte Medical

College, 1873-1879

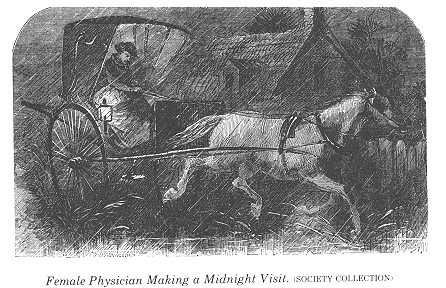

The number of women physicians in the

United States increased

dramatically during the late nineteenth

century. From a mere 200

or less in 1860, their ranks swelled to

over 7,000 by 1900.1 In Ohio,

the number of female doctors grew from

42 to 451 in the last three

decades of the century.2 Although reliable

statistics are not avail-

able, it has been estimated that a

majority of these women in Ohio

and elsewhere were trained in schools

sponsored by groups of physi-

cians who dissented from orthodox

medical therapy and were

branded as irregular sects by the

American Medical Association.3

Homeopathy, a major dissenting sect

which advocated extremely

small doses of medication, provided much

of this early educational

opportunity.4 In Ohio, for

example, the second woman to receive an

William Barlow is Professor of History

at Seton Hall University and David O.

Powell is Professor of History at C.W.

Post Center, Long Island University. The

authors wish to acknowledge the support

of the American Philosophical Society,

Penrose Fund, Grant Number 8438. A

shortened version of the paper was read at a

joint meeting of the Ohio Medical

Association and the Ohio Academy of Medical

History, Columbus, Ohio, May 15, 1979.

1. Mary Roth Walsh, "Doctors

Wanted: No Women Need Apply": Sexual Barriers in

the Medical Profession, 1835-1975 (New Haven, 1977), 186.

2. Frederick C. Waite, "Ohio

Physicians in the Nineteenth Century, A Statistical

Study," The Ohio State Medical

Journal, XL (August, 1950), 791-92.

3. Carol Lopate, Women in Medicine (Baltimore,

1968), 6.

4. Homeopathy was one of several medical

sects which emerged in the first half of

the nineteenth century and were

considered irregular because of their rejection of the

heroic therapy then practiced by most

orthodox physicians. Heroic medicine consisted

of extensive bleeding, blistering, and

sweating, together with drastic purging and

puking induced by massive doses of

calomel and other toxic substances. In contrast,

homeopathy was based on the law of

infinitesimals-the smaller the dose the more

effective the result-and provided

welcome relief to many patients formerly subjected

to the heroic regimen. Becoming popular

and somewhat fashionable in the middle

102 OHIO HISTORY

M.D. degree, Helen Cook, was graduated

from Cleveland

Homeopathic College in 1852. From that

date until 1914, 260

women earned homeopathic degrees in

Cleveland compared to only

64 regulars. Nationally, by 1880 nine of

the eleven homeopathic

schools admitted women.5

Explanations of the apparent absence of

sexual barriers in

homeopathy range from the noble to the

crass. They vary from the

sect's genuine dedication to a variety

of nineteenth-century reforms

including women's rights, through a

desire to spread its creed by

any means, including using women, to a

crude entrepreneurial

attempt to make money by expanding

enrollments in its educational

institutions.6 Whatever the

reason, historians have assumed that in

contrast to orthodox centers of medical

education, homeopathic col-

leges eagerly welcomed women. This

assumption has never been

examined in detail. Moreover, since

homeopathic medical schools

either disappeared or converted to

regular therapeutics in the twen-

tieth century, few materials remain for

a thorough and systematic

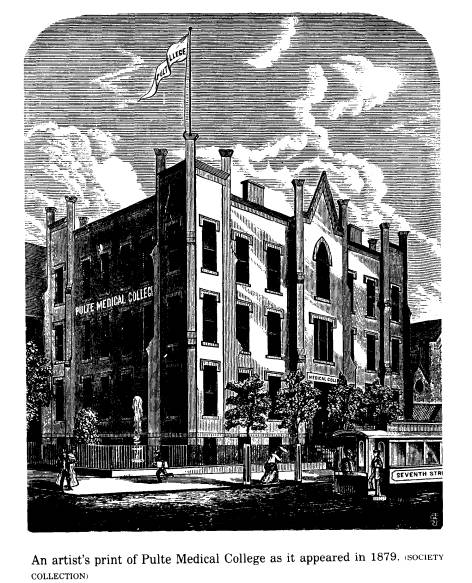

investigation. Fortunately, the records

of Pulte Medical College of

Cincinnati are extant and provide the

basis of this study.7

If Pulte was typical of her sister

colleges, the belief that

homeopathic schools ardently espoused

sexual equality must be

reexamined. From its founding in 1872

until 1879, coeducation was

hotly debated and proved so devisive

that it almost destroyed the

school. The wrangling reached a fever

pitch in 1878 when it was

taken up by the press and aptly

headlined "Homeopathic War."

Before the issue was resolved, it

produced mass resignations from

the Board of Trustees and faculty,

vitriolic personal attacks on pro-

fessors, and law suits charging libel

and slander.8

The dispute over female students at

Pulte did not occur in a

vacuum. It coincided with a national

debate concerning coeducation

prompted by the well-publicized views of

Dr. Edward H. Clarke, a

and late nineteenth century, homeopathy

established its own medical societies and

schools and was a major source of

competition to the regular profession. After the rise

of scientific medicine, homeopathy and

its medical institutions largely died out in the

early twentieth century. See Martin

Kaufman, Homeopathy in America: The Rise

and Fall of a Medical Heresy (Baltimore, 1971).

5. Frederick C. Waite, Western

Reserve University Centennial History of the School

of Medicine (Cleveland, 1946), 328, 330.

6. John B. Blake, "Women and

Medicine in Ante-Bellum America," Bulletin of the

History of Medicine, XXXIX (Spring, 1965), 99-123; Waite, "Ohio

Physicians," 792;

John Duffy, The Healers: The Rise of

the Medical Establishment (New York, 1976),

271.

7. Pulte Medical College Papers,

Cincinnati Historical Society, Cincinnati, Ohio.

8. Cincinnati Daily Times, June

13, 1878.

Homeopathy & Sexual Equality 103

Harvard Medical School professor. Dr.

Clarke argued that although

capable women had a right to study

medicine, they must be segre-

gated from male students and would be

hampered professionally by

their periodicity. His Sex in

Education; or, A Fair Chance for the

Girls, published in 1873, extended his argument against mixed

clas-

ses to include all female education

beyond puberty. Concentrated

study would divert "force to the

brain" which was necessary in the

"manufacture of bl od,

muscle, and nerve, that is, in growth." The

result would be women with

"monstrous brains and puny bodies ...

weak digestion . . . and constipated

bowels."9 The feminist counter-

attack was immediate. Articles, books,

and investigations quickly

appeared which concentrated on proving

that menstruation did not

impair women's ability to study or

work.10 The champions of women,

however, did not deal specifically with

the question of medical

coeducation.

That issue was at the time, however, in

contention at a number of

academic institutions. The University of

Michigan and several

other schools opened their doors to

women medical students early in

the 1870s. In 1878, the same year that

the Cincinnati squabble

reached a climax, even Harvard

considered coeducation. Conceding

that there was "a legitimate demand

for, and an important place to

be filled by, well-educated women as

physicians," the professors

nevertheless voted against their

admission. It is significant that

what was given at Michigan and denied at

Harvard was equal but

separate education. At Michigan the only

course in which the sexes

were integrated was chemistry. At

Harvard the rejected plan pro-

vided for "complete

separation" in laboratories and most lectures."

At irregular institutions from 1869 to

1877, six homeopathic schools

opted for coeducation, although several

restricted women to segre-

gated classes. By 1878, only Pulte and

two other homeopathic col-

leges remained exclusvely male.12

9. Walsh, "Doctors Wanted,"

119-27; Edward H. Clarke, Sex in Education; or, a

Fair Chance for the Girls (Boston, 1873), 41.

10. Walsh, "Doctors

Wanted," 127-32; Julia W. Howe, ed., Sex and Education: A

Reply to Dr. E.H. Clarke's "Sex

in Education" (Boston, 1874).

11. Bertha Selmon, "Early

Development of Medical Opportunity for Women in the

United States," Medical Woman's

Journal, LIV (January, 1947), 25-28, 60; Thomas

F. Harrington, The Harvard Medical

School: A History, Narrative and Documentary,

1782-1905 (3 vols., New York, 1905), III, 1223-34.

12. William H. King, History of

Homeopathy and Its Institutions in America (4

vols., New York, 1905), II, 211-14,

380-95, 410, III, 106-07. For examples of equal but

separate instruction at homeopathic

schools, see University of Michigan, Ann Arbor,

Michigan, The Homeopathic Medical

School, Second Annual Announcement, 1876-77

104 OHIO HISTORY

At the center of the protracted

confrontation over women at Pulte

stood four prominent faculty members:

Drs. Thomas P. Wilson,

M.H. Slosson, Seth R. Beckwith, and John

D. Buck. They were all

among the founders of the school, were

graduates of Cleveland

Homeopathic College, and, with the

exception of Dr. Slosson, had

taught there before coming to

Cincinnati. Drs. Beckwith and Slos-

son emerged as opponents of coeducation,

with Drs. Buck and Wil-

son as proponents. Other faculty members

took less consistent or

conspicuous stands during the

controversy.13

Either by intent or neglect, Pulte's

original bylaws and announce-

ments left the status of women

undefined.14 Consequently, at "every

session of lectures a number" of

women applied for admittance "but

were turned away."15 Such

was the fate of Frances Janney of Col-

umbus, Ohio. In 1874 her preceptor wrote

"to Cincinnati to see if

they would admit me this fall."

Denied acceptance, she entered Bos-

ton University where she received her

M.D. degree in 1877. During

the spring of 1876, however, she studied

in Cincinnati at Dr. Wil-

son's Ophthalmalic Clinic which was

housed in the same building as

Pulte. After Dr. Wilson persuaded some

of Pulte's teachers to permit

her to attend their classes

unofficially, she proudly informed her

mother that she would "be the first

lady student to attend lectures at

Pulte College after all." But other

professors, she complained,

"Beckwith among the number, say

they will not lecture to ladies

...." They were "not true

gentlemen," she felt, "& want to say

things they ought not to, & do not

want the restraint of the presence

of ladies."16 Thus,

despite Frances Janney's attendance at a few

classes, Pulte's doors remained formally

closed to women.

On four occasions from 1873 to 1878,

coeducation was debated and

voted on by Pulte's faculty. In 1873,

spurning the idea of mixed

classes, "a Spring Term for women

only" was approved. A circular

advertising the course was issued, but

since "not a single woman

(Ann Arbor, 1876), 3, and Tenth

Annual Announcement of Hahnemann Medical

College, Chicago, Illinois, Session

of 1869-70 (Chicago, 1869), 8-9.

13. Cleave's Biographical Cyclopaedia

of Homeopathic Physicians and Surgeons

(Philadelphia, 1873), 53, 319-20; King, History

of Homeopathy, II, 221-23, III, 36-61,

IV, 384-85.

14. Articles of Incorporation of

By-Laws of the Pulte Medical College, Cincinnati,

Ohio (Cincinnati, 1881); First Annual Announcement of

Pulte Medical College . ..

Session of 1872-73 (Cincinnati, 1872).

15. Letter, John D. Buck, William Owens,

Thomas P. Wilson to Board of Trustees

of Pulte College, June 11, 1878, Pulte

Medical College Papers (hereafter cited as

Buck et al. to Board of Trustees).

16. Letters, Frances Janney to Rebecca

A.S. Janney, August 7, 1874, May 3, 4,

1876, Janney Family Papers, Ohio

Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio.

|

Homeopathy & Sexual Equality 105 |

|

applied for admission," segregationist Dr. Beckwith concluded that women did not want to become physicians. Coeducationist Dr. Buck, however, exclaimed "Good for them," elated that women had repudi- ated sexual segregation in favor of full equality with men. Again in 1875 the question of admitting women was raised and "promptly |

106

OHIO HISTORY

voted down." Three years later on

February 5, 1878, Dr. Buck intro-

duced a resolution approving

matriculants "without distinction of

sex" which was passed, only to be

rescinded four days later. There-

upon, Drs. Buck and Wilson angrily

submitted their resignations to

the Board of Trustees and demanded an

"investigation of the lying

& bullying by which women were

excluded."17 When reconciliation

efforts failed, the trustees requested

that the two antagonistic fac-

tions present their ideas in writing in

order to provide a basis for

discussion and decision.18

The arguments for and against the

entrance of women to Pulte

were presented to the Board of Trustees

at a meeting on May 28,

1878.19 Speaking for a

majority of the faculty, Dr. Beckwith was

supported by Dr. Slosson and three other

professors. A longtime foe

of female physicians, Dr. Beckwith had

earlier fought unsuccessful-

ly to exclude them from local, state,

and national homeopathic orga-

nizations. By the 1870s, however, with

increasing numbers entering

the profession, he grudgingly admitted

that "no one denies her

right" and capability of

"practicing medicine." Even so, he doubted

if they could succeed as general

practitioners. "Nature" had adapted

women only for the "treatment of

disease peculiar to her own sex."

Furthermore, they must be trained in

"Colleges established for

them, or in entirely separate

departments" and only "for the very

limited sphere ... in which they can

reasonably hope to succeed"-

obstetrics, gynecology, and diseases of

children.20

But Pulte, Dr. Beckwith proclaimed, must

remain a male bastion.

It was "organized for the medical

education of men," and the "large

and intelligent" male student body

"almost to a man" opposed

female students. More importantly, mixed

classes would attract im-

moral women who would corrupt the "clinical instruction given to

male students." A separate

department for women was "utterly im-

practicable" at Pulte. Moreover,

lecturing to women separately on

surgery, anatomy, and obstetrics

"would be obviously improper and

embarrassing to all parties."

Adjunct female professors in these

sensitive chairs, Dr. Beckwith

continued, likewise would be un-

17. Letter, Seth R. Beckwith, M.H.

Slosson, C.C. Bronson, D.W. Hartshorn, W.H.

Hunt to Board of Trustees of Pulte

College, June 11, 1879, Pulte Medical College

Papers (hereafter cited as Beckwith et

al. to Board of Trustees).

18. Pulte College Board of Trustees

Minutes, 1872-1889 (hand-written copy), May

28, 1878, 72-74, Pulte Medical College

Papers (hereafter cited as Board of Trustees

Minutes).

19. Ibid.

20. Seth R. Beckwith, "Medical

Education of Women," Cincinnati Medical Ad-

vance, I (July, 1973), 304-06; Beckwith et al. to Board of

Trustees.

Homeopathy & Sexual Equality 107

acceptable "to the gentlemen

occupying them." In addition, even if

women were admitted to Pulte, they could not fulfill

the graduation

requirement of clinical observation and

lectures because the Cincin-

nati Hospital barred them from its

teaching facilities. In short, Dr.

Beckwith concluded, female students

would destroy "the harmony

and increasing popularity, usefulness

and prosperity of the Col-

lege." There the opponents rested

their case.21

The arguments for coeducation were

contained in an eleven-page

printed brief signed by Drs. Buck and

Wilson and part-time profes-

sor Dr. William Owens. A wide-ranging

document, it criticized the

organization of the board, attributed

the school's unstable finances

to Dr. Beckwith's antifeminism, and

mustered evidence from home

and abroad supporting coeducational

classes. Charging that Dr.

Beckwith had manipulated the members of

the Board of Trustees to

his will, the brief demanded that he be

removed as its president. In

that position, he had alientated "a

great and growing portion of

influential and cultured society."

More specifically, he was guilty of

the "slanderous assertion, broadly

and loudly advocated that no

respectable women will attend a Medical

College with men, and

that the College which admits them is

but another name for a

Whore House," thus casting

"offensive and indecent asperities on

women and sister Colleges" which

accept them.22

The brief went on to link certain

financial "failures and short-

comings" to Dr. Beckwith's refusal

to sanction coeducation. Dr.

Joseph H. Pulte, after whom the school

was named, originally prom-

ised a handsome endowment but after

women were excluded

changed his mind, stating that "his

wife, as his apothecary, had

done as much to establish Homeopathy in

Cincinnati as he had, and

he did not propose to take

her money as well as his own, to endow a

college that refused to her sex equal

rights and opportunities ...."

In addition, Dr. Beckwith's "out

spoken and violent opposition" to

women "greatly reduced the number

of our students" and thus

"most seriously affected our

financial revenues."23

In a more positive vein, the brief

argued that coeducation was in

keeping with the "spirit of the

present age, the progress of time, and

the course of medical education."

Even in "conservative Europe the

barriers" to women had crumbled at

the Universities of Paris, Lon-

don, Upsala, and Zurich, along with

other prestigious schools in

21. Ibid.

22. Buck et al. to Board of Trustees.

23. Ibid.; Cincinnati Daily

Times, June 13, 1878.

108 OHIO HISTORY

Italy, Russia, and Austria. On the

domestic scene, the recent May,

1878, Homeopathic Inter-Collegiate

Conference declared unani-

mously that "our" colleges

should be opened "to all . . . without

distinction of sex."24 While

attending that conference, Dr. Wilson

had solicited the candid evaluations of

coeducation from representa-

tives of the seven institutions where it

existed. Six replied in

lengthy letters which were included in

the brief. Eschewing all

theoretical speculations, the

respondents, some of whom were

formerly hostile to female students,

detailed the actual results of

mixed classes in their institutions and

thus provided a thoroughly

practical refutation of Drs. Beckwith's

and Clarke's tirades against

coeducation.25

Women, observed Dr. J.G. Gilchrist of

the University of Michigan

Homeopathic Medical College, were

intellectually "equal to the men

in exact knowledge . . . and class

standing." Dr. J.R. Sanders of

Cleveland Homeopathic College, on the

basis of"near twenty years"

experience, even felt that women

acquired "this knowledge with

greater rapidity" than men and held

"it with equal tenacity." Dur-

ing "the last year ... the best paper"

in Dr. Charles Adams' surgical

examination at Chicago Homeopathic

College "was from a women."

Women also possessed special healing

talents which "naturally en-

dowed" them for medicine, declared

Dr. A.C. Cowperthwait of the

Homeopathic Medical Department of the

University of Iowa. "For

the more delicate ministry of the

art," Dr. Sanders insisted, they

had "qualities prominent above

man."26

Although women were decorous creatures,

Dr. David Thayer of

Boston University had "no

trouble" instructing "both sexes together

on all subjects, even those of the

greatest delicacy." Dr. Adams had

"no more trouble with the cases in

my cliniques on account of their

presence than the gynecologist has with

his on the men's account."

Nothing had ever occurred in Dr. T.S.

Hoyne's lectures at Hahne-

mann Medical College of Chicago "to

offend even the most modest

woman in the land." Dr. Sanders

never had "any difficulty or embar-

rassment by reason of women's presence,

or ... any evidence of any

lady student suffering any offense, or

wound of delicacy, or tarnish

24. Buck et al. to Board of Trustees.

25. Letters, David Thayer to Thomas P.

Wilson, February 26, 1878; J.C. Sanders to

Wilson, February 26, 1878; J.G.

Gilchrist to Wilson, February 25, 1878; T.S. Hoyne to

Wilson, February 25, 1878; Charles Adams

to Wilson, February 25, 1878; A.C. Cow-

perthwait to Wilson, February 26, 1878,

Pulte Medical College Papers.

26. Letters, Gilchrist to Wilson,

Sanders to Wilson, Adams to Wilson, Cowper-

thwait to Wilson.

Homeopathy & Sexual Equality 109

of true womanly modesty." "If

this is possible in Obstetricy," he

emphasized, "it surely must be in

every other department of medical

teaching.27

The attendance of such superior moral

beings in classes with men

in fact "had a silently beneficial

effect on the sterner sex," reported

Dr. Gilchrist. Their presence at

Cleveland was a "perpetual chal-

lenge" to "boorishness and

vulgarity." The faculty there would nev-

er "forget the experience of

lawlessness, rudeness, unmannerly and

unmanly demeanor" of male students

at one session when women

were excluded. After women restrained

the animalistic male,

however, he exerted an "inevitable

challenge" to her "high endeavor

and rivalry of success." In short,

Dr. Thayer was convinced that

coeducation allowed a "healthy

emulation between the sexes which

contributes to the mutual advantage of

both."28

Finally, menstruation may account for

woman's "emotional na-

ture," wrote Dr. Gilchrist, but

rather than proving debilitating it

produced in female students an

"esprit de corps" which men lacked.

At the University of Michigan "in

not a single instance has a case of

break-down occurred among them, that

cannot be matched by

enough, yes, more than enough

cases among the men ... ." Women

were "equally enduring in the

strain incident to prolonged and

somewhat severe mental

application." "Dr. Clarke would find a

most overwhelming defeat of his system,

if he were here." Dr. Cow-

perthwait summarized the views of his

colleagues: "The day for

ladies to either starve or else be wash

and sewing ladies is past."29

Armed with these findings, the

petitioners requested not only the

admission of women but their full

equality as students, arguing that

"our College building is peculiarly

adapted to the wants of a mixed

class .. .." They indicated,

however, they would settle for less by

acknowledging "we have large

unoccupied rooms for separate clas-

ses when so desired." But for

their overall case, it could be "further

substantiated, if need be, by 'a cloud

of witnesses.' "30

Both factions of the faculty asked the

Board of Trustees for a

speedy resolution of the "vexing

question." Initially, by removing

Dr. Beckwith as its president and

forcing him and three other facul-

ty members to resign as trustees, the

board appeared ready to accept

27. Letters, Thayer to Wilson, Adams to

Wilson, Hoyne to Wilson, Sanders to

Wilson.

28. Letters, Gilchrist to Wilson, Thayer

to Wilson, Sanders to Wilson.

29. Letters, Gilchrist to Wilson,

Cowperthwait to Wilson.

30. Buck et al. to Board of Trustees.

110 OHIO HISTORY

women. However, the resignation of eight

additional trustees left

the remaining twelve divided and

uncertain as to how to proceed.

Therefore, at a series of meetings in

May and June of 1978, the

board procrastinated.31

Deliberations were further complicated

when the imbroglio

erupted in the public press. On June 13,

the Cincinnati Times pub-

lished segments of the "serious

charges against Dr. Beckwith" made

by Drs. Buck and Wilson. The following

day the Times joined by the

Enquirer and Commercial featured Dr. Beckwith's

denouncements

of the "libelous and

slanderous" accusations. These exchanges and

other newspaper reports centered on the

possibility of financial

irregularities and added little to the

women's question. On June 15,

Dr. Beckwith instituted a $10,000 libel

suit against Drs. Buck, Wil-

son, and Owens.32

Under such emotional circumstances, the

board met on June 18.

Conflicting resolutions were presented.

One stated that it would be

"detrimental ... to admit

females." A substitute resolution asserted

that matriculants "be admitted . .

. without distinction of sex" but

with separate lectures on certain

"delicate" topics. Unable or un-

willing to support either position, the

board after much maneuver-

ing deferred a decision until March,

1879. While the substantive

question was sidestepped, procedural

votes suggest that the board

was evenly divided.33 A

trustee later confessed that they "were in

doubt as to the wisdom and

propriety" of which course to follow. As

"business men," they were

"generally unacquainted with the real

merits of such questions" and

"hesitated when disaster and ruin

were predicted."34

Having postponed a verdict on

coeducation until the following

year, the board next considered the

seething hostility among the

professors. As with the women's issue,

they followed an erratic and

contradictory course. On July 1, Dr.

Slosson, spokesman for the

Beckwith group, introduced a plan

removing Drs. Buck and Wilson

from the faculty and adding five new

professors. In response to this

opportunity to clear the air, the board

temporized and inexplicably

accepted Dr. Wilson's resignation but

refused Dr. Buck's.35 A Cincin-

nati paper interpreted these actions as

a "triumpth for Dr. Beckwith

31. Board of Trustees Minutes, May 28,

June 3, June 11, 1878, 72-77.

32. Cincinnati Daily Times, June

13, 14, 1878; Cincinnati Enquirer, June 14,

1878; Cincinnati Commercial, June

14, 16, 1878.

33. Board of Trustees Minutes, June 18,

1878, 78-80.

34. Cincinnati Commercial, March

3, 1881.

35. Board of Trustees Minutes, July 1,

1878, 81-83.

|

Homeopathy & Sexual Equality 111 |

|

|

|

and his party" and concluded that the "question of the admission of women . . . is now practically decided in the negative." Dr. Buck retorted that such an assessment was "rather premature" because the "whole matter" was still "in the hands of the trustees."36 Dr. Buck's prophecy proved partially accurate. Within a month and without explanation, Dr. Slosson resigned and Dr. Buck's allies Drs. Wilson and Owens were reappointed by the board. In addition, two of Dr. Beckwith's former supporters now joined the Buck faction to form a pro-women faculty majority. Disappointed at his sudden loss of power and peeved by the board's probing into his financial conduct, Dr. Beckwith indignantly resigned. Therefore, by the fall term of 1878 professors supporting coeducation appeared trium- phant, and a favorable ruling on women by the trustees seemed assured.37 Such, however, was not the case. The board proved as incapable of resolving the quandary in 1879 as in 1878. On March 17, they decided to postpone "indefinitely" the "subject of the admission of

36. Cincinnati Commercial, July 3, 5, 1878. 37. Board of Trustees Minutes, July 31, August 2, November 23, 1878, 83-87. A special announcement dated August 1, 1878, was issued to clarify the various changes in the faculty during the hectic months of June and July. Pulte Medical College ... Session of 1878-79 (Cincinnati, 1878). |

112 OHIO HISTORY

women."38 Frustrated by

this delaying tactic, the faculty took mat-

ters into its own hands and published

the annual announcement for

1879-80 which proclaimed that

"hereafter all properly qualified

matriculants, without distinction of

sex, will be admitted."39

Presented with this fait accompli, the

board met on July 22 "for

the purpose of considering the action of

the faculty relative to the

admission of Females" but again was

hopelessly divided and unable

to assert control. After several

unsuccessful attempts to censure the

faculty for "infringement of the

privileges and duties" of the trus-

tees, the board appointed a special

investigating committee. After

deliberating for a week, the committee

submitted two conflicting

reports - one harshly criticizing the

professors, demanding a facul-

ty reorganization, and recommending that

the annual announce-

ments be destroyed, and the other

upholding the faculty and assert-

ing that in the absence of bylaws to the

contrary the admission of

students was a prerogative of the

professors. The board divided

evenly on both reports, and as a result

neither was adopted.40 Thus,

women were admitted to Pulte by the

faculty without sanction of the

Board of Trustees. In this unusual and

perhaps unprecedented

fashion, the controversy was finally

resolved.

The victory for the supporters of women

was less than complete.

In order to gain the necessary faculty

support and the reluctant

acquiesence of the trustees, Drs. Buck

and Wilson had compromised

the principle for which they had so long

fought. Coeducation would

not mean total integration of all

classes at Pulte. While promising

"women advantages equal, in every

respect, to those enjoyed by

men," the new announcement added

vaguely that "instruction will

be given in some departments separately,

whenever desirable or

necessary."41 In actual

practice, the sexes would attend segregated

classes in anatomy, obstetrics, and

gynecology as well as some of the

clinics.42

In the fall of 1879 seven women were

enrolled at Pulte. Observing

that three were college graduates and

two public school teachers,

the Cincinnati Enquirer proclaimed

extravagantly that their qual-

38. Board of Trustees Minutes, March 17,

1879, 94-95.

39. Annual Announcement of Pulte

Medical College ... Session of 1879-80 (Cincin-

nati, 1879), 13-14.

40. Board of Trustees Minutes, July 22,

29, 1879, 95-108.

41. Annual Announcement of Pulte

Medical College ... Session of 1879-80 (Cincin-

nati, 1879), 17.

42. Annual Announcement of Pulte

Medical College ... Session of 1880-81 (Cincin-

nati, 1880), 13.

Homeopathy & Sexual Equality 113

ifications were better than "any

class of male students in any

medical college."43 The

following year, 1880-81, saw eight female

metriculants, three of whom received

M.D. degrees. Dr. Buck

announced with satisfaction: "The

joint medical education of men

and women ... is no longer an

experiment."44 By 1883-84 women

comprised 31 percent of the students and

19 percent of the

graduates.45 While women

reported that they were welcomed with

"courtesy and respect," the

faculty asserted that their presence had

improved "general deportment"

and that they had displayed a "high

degree of scholarship."46 As

evidence, in 1880 Miss Stella Hunt re-

ceived the "prize for the best

examination in physiology," thus cast-

ing doubt on a famous obstetrician's

comment that woman "has a

head almost too small for intellect but

just big enough to love."47

Although the controversy over the

admission of women to Pulte

was eventually settled in favor of

common sense and justice, the

evidence suggests that sexual barriers

at irregular medical institu-

tions could be much more rigid than

scholars have assumed. A

majority of the faculty and trustees at

a homeopathic college were as

reluctant to embrace sexual equality as

were their counterparts at

most orthodox schools. Pulte's Dr.

Beckwith was as adamant in his

antifeminist stance as was Harvard's Dr.

Clarke. Moreover, even

when coeducation was adopted, it

involved, as elsewhere, equal but

separate instruction. Before

generalizing about the medical educa-

tion of women in nineteenth-century

America, historians must re-

search more completely homeopathic and

other irregular medical

schools. In fact, a thorough

reexamination of medical coeducation

seems necessary.

43. Ibid., 18-21; Cincinnati Enquirer,

March 24, 1880.

44. Annual Announcement of Pulte

Medical College ... Session of 1881-82 (Cincin-

nati, 1881), 20-23; Cincinnati Commercial,

March 3, 1881.

45. Annual Announcement of Pulte

Medical College... Session of 1884-85 (Cincin-

nati, 1884), 18-21.

46. Cincinnati Enquirier, March

21, 1880.

47. Ibid, March 5, 1880; C.D.

Meigs, Lecture on Some of the Distinctive Character-

istics of the Female, Delivered Before

the Class of the Jefferson Medical College, Janu-

ary, 1847 (Philadelphia, 1847), 62. For examples of examinations

written by one

woman graduate of Pulte, see Examination

Papers of Mary Wolfe, Pulte Medical

College, Class of 1883 (Cincinnati, 1883).