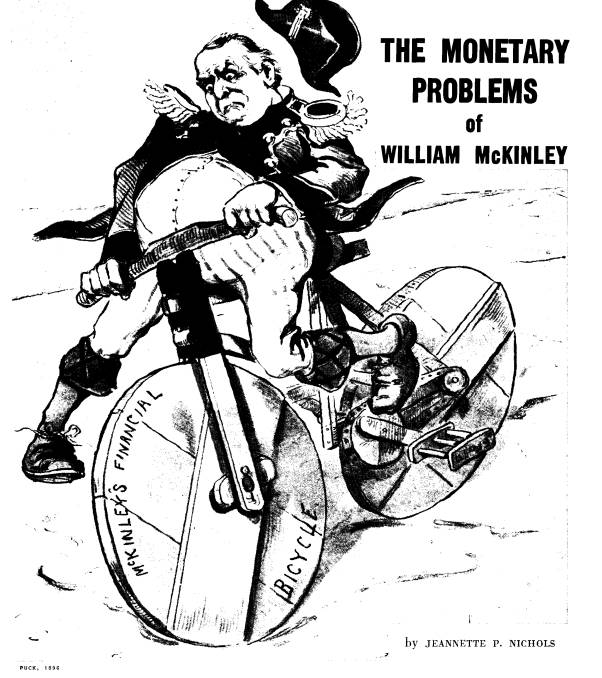

Ohio History Journal

|

|

|

The analyst of the career of a public figure functioning under a system of representative government finds that the problem of statesmanship is pecul- iarly complicated. The hazards in leadership often seem to conspire to punish statesmanship, confronting public figures with dire alternatives which subsequent biographers must not fail to weigh on the scales of the possible and probable. As McKinley bluntly explained when pushing a compromise to end a silver stalemate in the house of representatives: "We cannot have ideal legislation. It is not possible. Practical men do not NOTES ARE ON PAGES 341-343 |

264 OHIO HISTORY

expect it. Practical statesmen can only

strive for it, and secure the best

which is attainable."1

Successful politicians are not gods, but

mortals, growing from the earth

of their native heath, nurtured by the

ingredients of that soil. Firmly rooted

in it, they can bend like trees, before

stormy political winds sweeping over

the land of their constituency,

accommodating themselves to uncertain shifts

in direction and force. Toughened by

their practice in adaptation, such

men may wax in strength through the

years, negotiating the climb up the

political Mount Olympus. A few reach the

top. Such an one was William

McKinley.

A fair understanding of the record made

on an important political issue

by a highly successful officeholder

tests the mettle of the historian. One

must evaluate triple peculiarities:

those of the issue, the region, and the

person. In the relationship of the

twenty-fifth president of the United

States to the currency problem of his

era,2 there stand revealed three par-

ticularly dynamic factors: the peculiar

potency of the currency issue in

United States politics between 1860 and

1900; the irregular pattern of

political behavior then in Ohio; and the

embodiment, in McKinley's person-

ality, of the disposition and skills

essential to a successful fusion of the

issue, the region, and a career.

The following narrative begins with

brief descriptions of the three most

dynamic factors pertinent to this subject,

and proceeds therefrom into the

emergent sequence of events.

The peculiar potency of the currency

problem in United States politics

between 1860 and 1900 arose chiefly from

the economic and social insta-

bility experienced by the populace.

America was establishing the basis

for unprecedented national productivity,

and demonstrating phenomenal

recuperative powers after adversity, but

the pace of change was so rapid,

and so frequently raised urgent

problems, that painful groping for answers

was a common experience. The nation was

demonstrating that under a

representative form of government

economic status is a political fact of

prime importance, making shifts in that

status a prime cause of political

instability.

Anyone born in 1840 and living into 1900

experienced in his adult life

three severe depressions (1857-59,

1873-78, 1893-98) and at least four

minor recessions (1881, 1884, 1888, and

1890). He was caught up in

the rushing current of an unprecedented

national expansion--in area, popu-

lation, and wealth--without a

correlative expansion in the circulating

medium needed to oil the economic

machinery.

McKINLEY'S MONETARY PROBLEMS 265

Furthermore, the American was without

the protective services of a

central bank or other institution

expressly assigned the task of striving to

cushion ups and downs of the economy.

Whenever, for many complicated

reasons, the economic machinery lost

momentum, slowed down miserably,

and stripped its gears, innumerable

delicate parts got "out of whack."

Ambitious and solicitous tinkerers,

blessedly unaffrighted by the intricacy

of the mechanism, rushed to the rescue,

each with his own design of a new

monkey wrench. No conflict lacks its

appeal to pseudo science as well

as science.

Many of the repairmen concentrated their

endeavors on the currency

area of the mechanism--one of its most

delicate parts and nearly defense-

less against the well-meaning

self-confidence native to the American demo-

cratic tradition. Some daring

technicians sought to alter, or remove alto-

gether, that part of the machinery known

as the gold standard; decades

ahead of their time, they argued against

forcing a distressed national

economy to pay obeisance to that

imperious concept of international

respectability.

Less daring repairmen, remembering that

printing-press money had

helped to finance the Civil War,

proposed to fight depression with issues of

paper to be maintained "as good as

gold" by the fiat of their growing

country. The more timid, fearful of

"soft" money, counted on the same

fiat to maintain hard money--depreciated

silver--on a basis of "equality

with gold"; to these mechanics

"bimetallism" was the magic lubricant.

Perforce, the currency issue acquired

both national and international conno-

tations: of class conflict, of intra- and

inter-regional jealousies, of intra-

and inter-party rivalries, of

nationalism and isolationism.

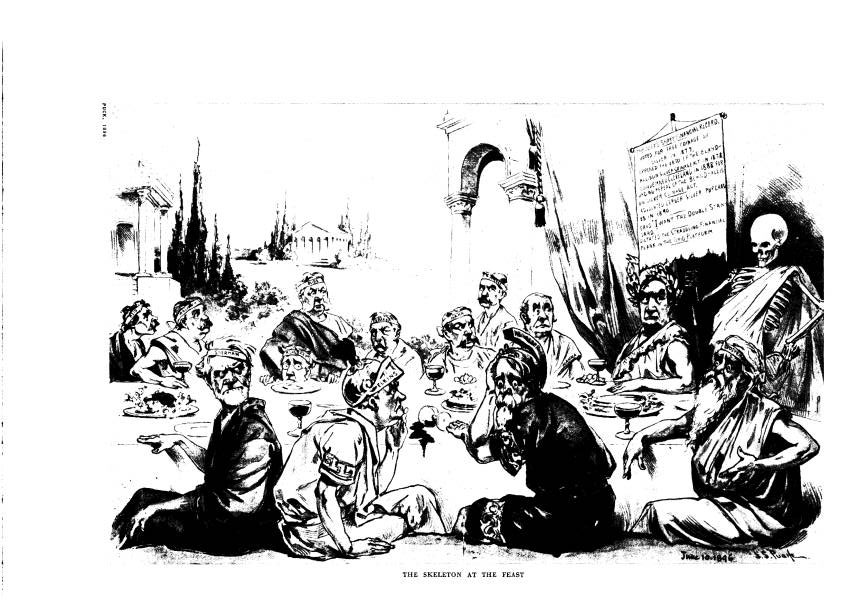

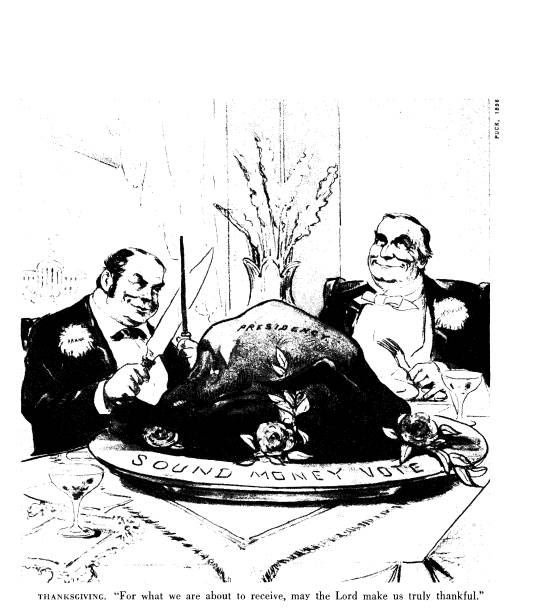

The result was a melange of fantasy,

friction, and faction, challenging

the understanding and ingenuity of

everyone, especially persons subject

to the electorate. The enormously

difficult currency problem thus exer-

cised a peculiar potency to raise, and

wreck, political careers. This potency

warned William McKinley to keep at a

safe distance from the radioactive

issue. Ultimately, as will be seen, he

stationed himself safely behind a

shield fused of patriotism, bimetallism,

and the tariff.

The irregular pattern of political

behavior in Ohio rested upon an his-

toric, pre-Civil War, partisanship and

became aggravated by postwar eco-

nomic diversification. As in some other

midwestern states, strong agricul-

tural interests survived amid burgeoning

industrialization, with sharp

diversities in population movements,

occupations, and the momentum of

activity. Political unity within parties

was hard to come by, with personal

266 OHIO HISTORY

rivalries and rank inconsistency often

at a premium as devices for affecting

the balance of power in the party

machine. By the same token, statesman-

ship--the reconciliation of divergencies

for the overall good--was an

arduous endeavor, highly punishable.

Candidates had to thread a veritable

Minoan labyrinth. John Sherman and

William McKinley became the two

Ohio politicians who, Theseus-like, were

most successful in keeping hold

of a thread strong enough to lead them

safely through the maze.

Ohio furnished a sharp contrast to New

England's secure postwar hier-

archies of Republicanism, on local,

state, and national levels. McKinley's

own county, Stark, remained almost

constantly Democratic (as did Sher-

man's Richland County), and his

congressional district was so closely

fought that it was gerrymandered five

times out of the seven races he ran

for the house of representatives from

1876 to 1890. In his hair's breadth

contest of 1882 McKinley finally lost

out by eight votes. The Republicans

were the minority party in the lower

house in all but four of the more than

thirteen years he served in congress;

and, in those four, greenbackers and

silverites made their legislative

presence known.3

Ohio during the 1860-1900 era gave her

gubernatorial terms to Demo-

crats four times; her congressional

terms ran approximately forty-five

percent Democratic until the depression

beginning in 1893, a political

windfall for the Republicans which so

increased their longevity in the house

as to raise their forty-year average to

a shade above sixty percent. Her

senatorial terms went to Democrats five

times out of fifteen, with six of

the Republican victories won by Ohio's

other masterly middle-of-the-roader,

the Republican Nestor, John Sherman.

This left only four terms for less-

skilled Republicans. Sherman tenaciously

kept a seat in the United States

Senate through two sixteen-year periods

(1861-77, 1881-97), broken only

by four years as secretary of the

treasury under President Hayes; but his

senatorial colleague from Ohio was

always a Democrat after bluff old Ben

Wade left the scene in 1869. Here indeed

was rigorous training making

for an acute sensitivity to partisan

potentials.4

Ohio's political irregularity was an

invitation to monetary enthusiasms;

but in such uncertainty precise

definitions were usually to be avoided like

the plague. Democrat or Republican,

Ohio's senators and representatives,

when traversing monetary ground, had

best walk on eggs. Thus, the

unending practice of vague

generalization became an ever-present fact of

McKinley's life, annoying opponents,

biographers, and historians, and (as

will be seen) fooling the platform

drafters in 1896.

Right John Sherman

268 OHIO HISTORY

McKinley, the individual, embodied the

disposition and skills essential

to a successful fusion: of the volatile

monetary issue, of Ohio's political

fickleness, and of his own career in

Republicanism. Rooted deeply in the

mid-Victorian mores of a middle-class,

midwest environment, he consist-

ently aimed always to keep within the

bounds of a middle position. His

ambition wore too gentle a guise to defeat

his advancement, making usually

for a comfortable feeling among most of

his associates.

He sought preferment through avoidance

of leadership: through caution,

ingrained indirection, passivity,

postponement, neutrality, temporizing, lis-

tening, earnest oratory, and (where moot

issues were involved) through

strategic silence or skillful use of a

maze of familiar-sounding, more-or-

less-sacrosanct verbiage. McKinley

possessed the inner strengths peculiar

to sincerely cherished mediocrity. His

native optimism could not be weak-

ened by doubts stirred in broad study of

vagrant monetary philosophies;

he learned "by ear" and

confined his reading almost exclusively to

newspapers.

McKinley attended a school of experience

with a comparatively light

monetary curriculum. He never had to

endure the bitter opprobrium of a

secretary of the treasury (such as

Sherman) commissioned to achieve

resumption of specie payments before

Americans could forget a long-

lasting depression. He never had to

direct the vast patronage of the treasury

department under a president (such as

Hayes) committed to cleansing the

Augean stables of corruption.

Altogether, this lucky politician enjoyed a

simple philosophy, undisturbed by any

very disquieting awareness of the

basic socio-economic problems of the

nation; surely, he thought, high protec-

tion could solve most economic problems,

including monetary issues. Thus,

McKinley need never be given to

following new paths, other than those

blazed by the emotions of his fellow

countrymen. To these emotions, within

the range of his basic principles and

his simple understanding, he conscien-

tiously sought to give heed. Of this, he

made a capital demonstration as he

threaded his way through the monetary

politics of his era.

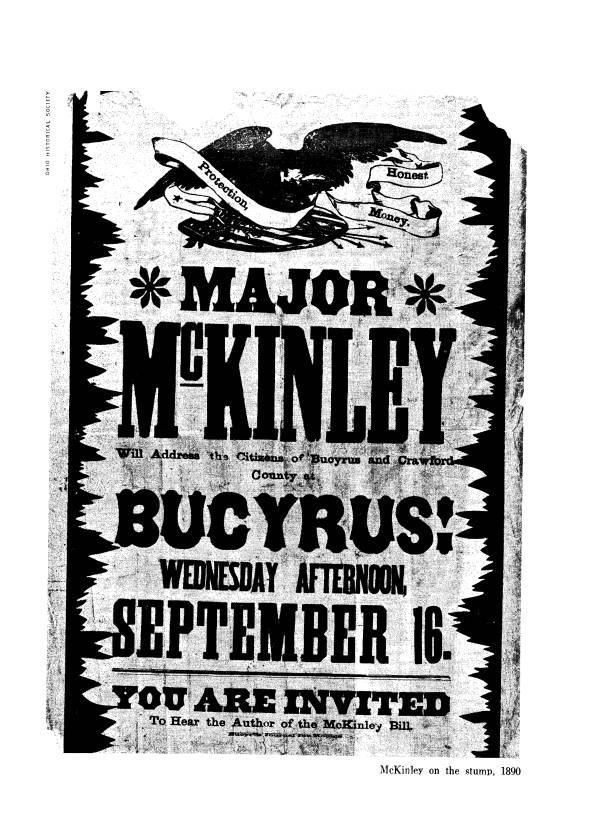

McKinley sallied into politics early--in

1867, before the fledgling

lawyer was twenty-five years old. Ohio

decisions were typically uncertain,

and his experiences as a local

campaigner during the next nine years taught

him a great deal about monetary

politics. He helped get the governorship

for his Civil War commander, Rutherford

B. Hayes, in the hair-line contest

of 1867, bringing in Democratic Stark

County for Hayes. But the legis-

lature proved to be Democratic on joint

ballot by eight votes, ensuring that

Senator Sherman's next colleague would

be a Democrat, Allen G. Thurman.

McKINLEY'S MONETARY PROBLEMS 269

One reason for the Democratic majority

at Columbus was the rise of

greenbackism.5 The flow of

debtor payments into the banks and into the

East was creating a currency scarcity,

aggravated by the treasury's policy

of greenback retirement preparatory to

resumption of specie payments on

a gold basis. Greenbackers demanded new

issues of greenbacks for retire-

ment of the bonded debt; they aimed to

decrease both the national debt

and interest charges on it, and to

increase both the supply of currency for

paying their own debts and the prices

paid to them. Radical Democrats

seized on this issue as one calculated

to restore their party to power and

pushed less-daring Democrats and

Republicans into various concessions

on it.

So McKinley began his lifetime

adjustments to the monetary issue during

his novitiate. The "rag baby"

proposition was coming to be called the

"Ohio Idea" because of its

strength in his home state. The formerly con-

servative Cincinnati Enquirer was

vociferously popularizing it, and out-

standing advocates of various greenback

solutions included Ohio's vigorous

ex-Republican Greenbacker, Samuel F.

Cary, and her less radical but very

prominent Democratic presidential

aspirant, "Gentleman" George H.

Pendleton. His moderate "Pendleton

Plan" for using greenbacks as a

means for achieving specie payments was

endorsed, January 8, 1868, by

the state Democratic convention; and a

month earlier both Ohio's senators

and all her congressmen but two had

helped to pass a law to suspend further

reduction of greenbacks.6 What

platforms would the national parties pro-

vide for use on Ohio hustings?

The Republicans officially denounced

"all forms of repudiation," gently

adding that the public debt should be

paid gradually, at an honestly reduced

interest rate, in good faith according

to the "letter" and "spirit" of the

laws; but several of their state

conventions and some leaders leaned on the

Pendleton Plan for support. The

Democrats officially endorsed it, declaring

that such public debt as was not

expressly issued as payable "in coin . . .

ought, in right and in justice," to

be paid in "lawful money"; but they

finally passed over Pendleton, to

nominate an embarrassing anti-Greenback

New Yorker, Horatio Seymour.7

Ohio's Republicans, fortified by Grant's

military popularity, cannily

sought votes on both sides of the monetary

fence. Their state platform

advocated war-bond redemption "in

the currency of the country which may

be a legal tender when the government

shall be prepared to redeem such

bonds." Senator Sherman cagily

pronounced that the government had the

right to redeem in "existing"

currency but not in a new issue emitted for

|

|

|

the purpose. McKinley found an out by pitching his speeches on the great- ness of Grant as a military leader. Using Grant and such fluid propositions as these, Ohio's Republican campaigners lost only three of their current congressional seats (retaining thirteen of Ohio's total nineteen) but eight of their men won by majorities under 1,000 and Grant proved much stronger than his party. Within two weeks after Grant's inauguration, two Ohioans, Senator Sherman and Representative Robert C. Schenck shepherded through congress a bill endorsing payment of government bonds "in coin or its equivalent," and Grant signed it.8 McKinley and other Ohio faithful next bent their efforts to winning back their state legislature and reelecting Governor Hayes in 1869. While the Democratic state platform reiterated that bonds should be paid in green- backs, the Republicans omitted mention of greenbacks. McKinley's party |

McKINLEY'S MONETARY PROBLEMS 271

felt confident of prosperity and he

accepted the dubious honor of nomination

for Stark County prosecuting attorney, a

place the Democrats usually held.

He won, surprisingly. So did Hayes; but

their party's control of the legis-

lature was somewhat diluted by

"Liberal Republican" members. During

the next winter national interest in the

currency sufficed to bring nearly

fifty variegated monetary measures into

the congressional hopper.

The state campaign of 1871 was hard

fought, but there was then less

political percentage in the greenback

issue (temporarily in abeyance) than

in the fact that the new legislature

would determine whether John Sherman

should win another term. Again the

Democrats officially endorsed the

Pendleton Plan and the Republicans

omitted it from their platform. The

Republicans won the legislature

narrowly, but were badly factionalized.

Sherman had a near miss, winning by only

two votes on joint ballot. This

escape from defeat was enviously

explained by Congressman James A.

Garfield, who claimed that Sherman had

the regular habit of being "very

conservative for 5 years and then

fiercely radical for one."9

Quietly observant and listening,

McKinley returned to private legal prac-

tice that fall. Before he again sought

public office (in 1876) he saw

abundant evidence of monetary hazards to

Ohio candidates. Her repre-

sentatives in Washington were moved to

introduce bills of varied hues of

monetary doctrine, while they won and

lost their Ohio campaigns by narrow

squeaks, eschewing platform consistency.

After the depression descended

in 1873, twelve of their twenty house

members voted for a permanent increase

of greenbacks up to $400,000,000; but

neither Ohio senator, Sherman or

Thurman, voted for it, and Grant vetoed

it.10 Nine Ohio congressmen voted

against the historic act of 1875 which

specified ultimate contraction of legal

tender notes to $300,000,000 and

resumption of specie payments by

January 1, 1879.11

Protest against contraction flamed high

in Ohio in the summer of 1875,

for reasons besides agricultural

distress, alarming both the major parties.

Newcomers to the Ohio Democracy were

employing greenbackism to gain

party influence; and over-extended

investors in Ohio's iron, coal, railroads,

and growing heavy industry saw ruin in

deflation.12 The party abandoned a

recent tolerance of resumption and distaste

for irredeemable currency.

Uttering dire warnings of disaster from

resumption, their boldest element

got a platform demanding repeal of the

offensive law, displacement of bank

notes by greenbacks, and maintenance of

a volume of currency "equal to

the wants of trade." This was a

little too much for Democratic Senator

Allen Thurman; he occasionally assured

the voters that his party neither

opposed resumption nor demanded

inflation.

272 OHIO HISTORY

The Republicans adopted a gradualism the

Democrats recently had advo-

cated; they declared for a financial

policy which should "ultimately equalize

the purchasing capacity of the coin and

paper dollar . . . without unneces-

sary shock to business and

trade"--an implication of postponement useful

with disaffected audiences. Also they

found it better to place their emphasis

on the horrors of inflation rather than

the beatitudes of resumption. They

employed moral appeals: irredeemable

currency was "unsound," a viola-

tion of a "pledge." After

using these tactics to soften the impact of Hayes's

bolder defense of resumption, and after

fervid oratory from Carl Schurz,

imported to remind the Germans of the

dire evils of inflation, McKinley and

other ardent campaigners won in 1875 a

third term for ex-Governor Hayes,

but narrowly.13

McKinley knew that the currency issue

was splitting his party. William

D. Kelley, an outstanding protectionist

whom Pennsylvania Republicans

established in congress in 1861 (and who

was destined to occupy that seat

until death ousted him in 1890), had

been converted to greenbacks in 1866;

in 1875 he had been invited into Ohio's

hard-hit iron and mining districts

to campaign as a Republican opponent of

resumption and national banks.

Sagely accepting party double-talk as a

plain fact of political life,

McKinley decided that Hayes's candidacy

for the presidency in 1876 was

a good time for him to run for congress.

He easily balanced resumption on

one shoulder and bimetallism on the

other, trying out the tariff as a "minor

issue";14 and the Ohio

state Republican committee was equally dextrous,

balancing Hayes with Kelley, especially

as Youngstown steel manufacturers

liked Kelley's protectionism. As Kelley

jocularly reminded his fellow

representatives, Republicans and

Democrats, it was "a very convenient

thing" for his party to be able to

send him, a Republican greenbacker, a

"convertible bond man," into

greenback districts of Ohio, Indiana, and

Pennsylvania. With becoming gratitude

Hayes and Congressman Charles

Foster--but not Garfield, an unswerving

hard-money man--had endorsed

Kelley's own candidacy in appropriate

quarters of Pennsylvania.15

While the national Republican platform

of 1876 endorsed "continuous

and steady progress to specie

payment," the point was rather a quiet aside

in a clamorous waving of the bloody

shirt.16 Despite, or perhaps because

of the existence of a Greenback party,

Ohio Republicans managed to give

to Hayes a presidential majority of

6,636 votes, and to their slate--includ-

ing McKinley of Stark--twelve of the

twenty congressional seats. The

ultimate seating of Hayes, and his

selection of Sherman as secretary of

the treasury, opened the senatorship to

an ex-Democratic supporter of

|

|

|

Hayes, Stanley Matthews, who in monetary matters proved left of center-- counting McKinley as center, Sherman as right of center, and Hayes with Garfield as farther right. Amidst the clamor over the depression, greenbacks, and the rigged elec- tion returns, Ohio's legislators found surcease in silver. The majority of her congressmen regardless of party but lacking Garfield, voted December 13, 1876, for free coinage,17 and her state legislators proceeded in 1877 to pass a resolution favoring silver remonetization. The freshman congress- man from the Democratic county of Stark stood up and was counted for silver coinage within twenty-one days after he took his seat; and by March 1, 1878, resumptionist McKinley had gone on record for currency expan- sion thrice, and against it once. Together with all Ohio's congressmen except Garfield (who was absent and unpaired), he supported the latest Bland bill |

274 OHIO HISTORY

for free coinage, November 5, 1877.18

But he promptly thereafter voted

against repeal of the 1875 resumption

clause.19

His coupling of free silver with specie

resumption came easily to

McKinley that November. His home-town

newspaper said that silver would

"strongly aid" resumption

because two metals would be used; silver

remonetization therefore was not

inflationary and, besides, it signalized

defeat of "eastern money

sharks" and "European money lenders." The

Canton Repository lauded his type of ambivalence and deplored different

angles adopted by such seasoned

politicians as Garfield, Hayes, Matthews,

and Sherman.20

As the winter wore on McKinley continued

to learn by ear, listening

while for three exciting months senate,

house, administration, and nation

argued over free coinage. Secretary of

the Treasury Sherman noted that

commerce was favorable and gold was

accumulating in the treasury, but

under the silver uncertainty he avoided

bond sales, "awaiting events without

any committals whatever."21

Back in Columbus the assembly noted that an

1877 declaration for free coinage had

passed with only three nays in their

house and one in their senate, and they

reiterated that "common honesty,

true financial wisdom, and justice to

the taxpayers of this country, demand

the immediate restoration of the silver

dollar to its former rank, as a legal

tender for all debts, public and

private."

The Democratic brethren among them,

being in the majority, made it a

personal matter, sending notice to every

Ohioan at the national capitol "that

President Hayes and Secretary John

Sherman, in their opposition to the

restoration of the silver dollar, do not

represent the views of, nor the wishes

of the people of the State."22

The majority expressed their own wishes by

electing to the senate Pendleton of

greenback fame. There would be no

Ohio Republican in the senate for the

next two years to grease the ways for

McKinley projects there.23

Over in Washington, Stanley Matthews was

pressing through the senate

a resolution declaring that it did not

violate public faith nor derogate

creditor rights to make government bonds

payable, principal and interest,

"at the option of the

government" in silver dollars.24 Secretary Sherman

was insisting that, until the government

was ready to redeem greenbacks

"in coin," holders of them

should be allowed to convert them into four

percent bonds at par;25 but

he was opposed to free coinage.

As this was the decade when the house

was the branch most addicted to

currency expansion, it was the senate

which here provided a remedy. Con-

veniently attaching the name of a

midwestern senator to a mild substitute

McKINLEY'S MONETARY PROBLEMS 275

for Bland's unlimited coinage, the

senate sent back to the house the famous

(or infamous, depending on viewpoint)

Bland-Allison bill, carefully tailored

to obtain a two-thirds vote in both

houses. It met part way three different

clamors: the popular demand for currency

expansion, the mine owners'

demand for a market, and the

conservatives' demand for recognition that

America's international repute was involved.

The government was to spend monthly no

less than $2,000,000 and no

more than $4,000,000 for bullion bought

at the market price (then about

ninety cents for the content of a

dollar); it was to coin it into silver dollars

which were to be "legal tender"

and which could be exchanged at the treas-

ury for "silver certificates"

in denominations of no less than ten dollars;

the Hayes administration must call an

international bimetallic conference.

This compromise got the votes of both

senators, McKinley, and sixteen of

the other Ohio representatives,

including Garfield. The other three repre-

sentatives were not rewarded with long

terms in the house.26

Would the president from Ohio accept it

or veto it? Secretary Sherman

was dubious about a veto. He suggested

to Hayes that the minimum pur-

chase of $2,000,000 worth at the market

price, with the government pocket-

ing the difference between actual cost

and the stamped value, should remove

"all serious objections,"

especially "in view of the strong public sentiment

in favor of free coinage." But

Hayes's sense of moral values was aroused;

he was not so sure that even the minimum

could be kept at par with gold;

"the nation must not have a stain

on its honor." He vetoed, and house and

senate promptly overrode that veto. The Repository

explained the desertion

of Hayes by his friends from Ohio:

"It was not that they loved Hayes less

but that they loved tranquility

more."27

But what about McKinley? What had

happened to the thirty-four-year-old

resumptionist of 1875? In truth, he was

putting on a pair of mismated

monetary shoes which he wore comfortably

on his stroll through politics

over the next twenty years. One foot

wore a shoe of continued opposition

to currency expansion through emission

of paper unbacked by metal. The

1875 Schurz type of argument had

convinced him of the rightness of that

opposition--of that kind of support for

resumption. Its advocates bore the

aura of fortitude; as McKinley modestly

explained in referring to Garfield's

insistence on resumption, "No act

of his life required higher courage."28

The other shoe was half-soled with

silver.

McKinley found in silver expansion of

the currency the moral, patriotic,

and "sound" policy to adopt.

Morally, a wrong needed righting. Like

millions of Americans then and

recurrently since, he tended to accept the

276 OHIO HISTORY

"Crime of '73" doctrine which

able inflationists and mine owners endlessly

dinned into receptive ears.29 The

doctrine argued that silver had been

"unjustly deprived" of its

"rightful place" in the American bimetallic

system when the mint act of 1873

"secretly" and through "wicked machina-

tions by a British agent of London

bankers" had failed to include the silver

dollar in the list of pieces authorized

for coinage.

Herein McKinley parted from Garfield,

Hayes, Sherman, and others who

pointed out that the act was long

debated, the silver dollar was not then in

use, and the supposed "agent"

was himself an internationally known

bimetallist. McKinley thought it

"unjust" that rich advocates of gold should

keep from the poor the use of silver--a

conviction reinforced by impolitic

comments from gold spokesmen.

Patriotically, McKinley must resent any

masterminding by British cred-

itor interests. Furthermore, United

States use of bimetallism was an his-

torical custom hallowed by the

constitution and by Hamilton's projection

of it in 1792. McKinley's faith in it

was not undermined by the fact that

under American experience with bimetallism,

silver and gold had chased

each other in and out of circulation as

one or the other metal reached a

market value above the current coinage

ratio.30 Our great democracy must

hold to its priniciples. Also to an

ambitious congressman who was by way

of becoming engrossed in

"protection" as a sure solution of domestic prob-

lems, American-produced silver merited

that "recognition" which limited

coinage provided. Congress must "do

something for silver."

McKinley found limited silver coinage,

at the approximate ratio of

sixteen to one, "sound" for

many reasons. The metal had been valued in

the marketplace above that ratio for

eighteen years. Silver did not carry

the deep stain of

"inflationary" greenbacks. The resumption act specified

"coin," not gold, affording

silver high respectability and opening avenues

of further use. Besides common folk,

some notable economists, statesmen,

and reputable journals were arguing that

gold, alone, had demonstrated its

inadequacy as a monetary base. The

European powers deserting bimetal-

lism of late must shortly cooperate with

the United States in restoring it;

their economic need for an international

bimetallic agreement was being

preached by bimetallic leagues

(maintained by minority intelligentsia) in

England, France, and Germany.

Meanwhile, McKinley and many other

resumptionists believed that our

United States could keep a limited

volume of silver legal tenders "as good

as gold." All United States money,

"the money of the poor no less than

the rich," must be "as good as

gold," of course. Certainly for McKinley

McKINLEY'S MONETARY PROBLEMS 277

and many other congressmen of his type

of personality, limited economic

grasp, schizophrenic constituency, and

conservative Republicanism, a modi-

cum of silver legal tender acquired a

validity which suited the convenience

and satisfied the conscience.

The McKinley who had voted, November 5,

1877, for Bland's free coinage

bill had vanished three months

later--never more to return. He had become

a limited bimetallist. The breed

aggravated Bland and his ilk, because

McKinley and his ilk would not agree

that the United States could open her

mints to the silver of the world

"without waiting for any other nation on

earth." The breed confounded the

gold standard advocates because it did

just enough for bimetallism to hang

silver like a Damocles sword over the

heads of the president and the

secretary of the treasury.

The breed never "ran true"; it

fathered all sorts and conditions of men,

bipartisan, erratic in everything

except unwillingness to stop "doing some-

thing for silver." Through fifteen

years, to the infinite annoyance of five

successive presidents, it held the

balance of power in America's monetary

politics and diplomacy. McKinley

remained faithful to the main tenet of

this group through these years, as

representative, as governor, and, later

for a brief space, as candidate for the

presidential nomination.

During this period of comparative

consistency, McKinley's monetary

tread could proceed at a measured pace,

until 1889, when he quickened it

sharply for a few months prior to his

defeat for reelection to the house of

representatives. His monetary

experience between April of 1878 and Decem-

ber of 1889 therefore requires only

summary treatment.

Republican party managers, in the

nation and in Ohio, hoped that the

Bland-Allison act had put the silver

issue in a deep coma; and intermittent

upward trends in business occasionally

provided a subdued lullaby. But

the few free-coinage diehards, from

both parties, strove to make enough

noise to waken the sleeper and had

their decibels magnified at times by at

least four helpful amplifiers. The

comparatively mild recessions of 1881,

1884, and 1888 encouraged popular yearnings

for currency expansion and

some businessmen complained that they

were constricted.

Also, Democratic party managers were

not deaf, powerless, or asleep;

holding control of the house from 1875

to 1881 and from 1883 to 1889

(and near control of the senate

1881-83) they exploited silver at such

times and in such places as it had

appeal. A fourth group was those silver-

mine owners who looked somewhat askance

at Bland-Kelley-Warner bills

to admit foreign bullion to the United

States mints, but cooperated with

bullion speculators in rousements. They

were disappointed at the failure of

McKINLEY'S MONETARY PROBLEMS 279

the minimum Bland-Allison purchases to

sustain the bullion market; through

free coinage oratory congress might

again be aroused to "do something

for silver."

Congress found the various types of

silver lobbyists infiltrating the nation.

As McKinley's colleague on the banking

and currency committee, Congress-

man Edwin H. Conger of Iowa, reminded

the house: "You cannot point

to a single locality where free-coinage

resolutions have been adopted, nor

a single paper which has advocated the

free coinage of silver, except you

find in that locality the foot-prints of

the silver-bullion owner or his agents

or else the mark of the men who are

employed by them."31

Much of the monetary activity had little

effect before 1890. The amount

outstanding of greenbacks was frozen at

$346,681,016 on May 31, 1878;

but on December 17, following, Wall

Street dealt in greenbacks at par. A

concurrent resolution, fathered by

Ohio's inflationist Senator Matthews, had

declared that bonds issued under the

refunding act of July 14, 1870, and the

resumption act of January 14, 1875, were

payable in gold or silver, but "at

the option of the government," and

all the administrations were notorious

for their addiction to gold.32 Ohio

Republican candidates of 1878 had a

state platform opposing "further

agitation of the financial question," and

some of them vouchsafed that they should

be reelected because their party

had given the nation the greenback,

which should be worth "one hundred

cents on the dollar."

Garfield's victory over Sherman in the

race for the Republican presiden-

tial nomination in 1880 turned largely

on comparative warmth of person-

ality, but the delegates knew, also,

that Sherman was more vulnerable,

nationally, as a target for advocates of

cheap money. His enemies sometimes

spoke of bankrupts as

"Shermanized."

McKinley's bimetallic stance was

protected by a secret agent from Ohio,

and by Congressman Kelley of

Pennsylvania. S. Dana Horton, a multi-

lingual Ohioan committed to bimetallism

if maintained by international

agreement, functioned as secretary of

the international bimetallic conference

assembled at Paris in 1878 in accordance

with the Bland-Allison command,

and during the next decade managed to

obtain repeated employment on

confidential missions under Arthur and

Harrison.

Horton, and weightier confidential

agents sent by each administration

during the decade, tried to scare England,

France, and Germany into various

forms of recognition of silver as a

monetary metal, threatening that other-

wise congress would terminate purchase

of United States silver, its market

value would fall further, and their own

business relationships would suffer.

280 OHIO HISTORY

Unfortunately for the American

emissaries, Democratic and Republican

congresses gave them the lie. The

Europeans knew that the monetary

balance of power in the United States

lay with McKinley and his kind.33

Completely effective in blocking

cooperation from Germany was the high

chief of the free coinage men in the

Republican party. The ebullient Con-

gressman Kelley, traveling abroad and

sending back columns to the Phila-

delphia Times, secured a teatime invitation from the Iron Chancellor.

Bismarck asked Kelley what the United

States would do if European govern-

ments would not cooperate for international

bimetallism. Kelley promptly

assured him that congress in that case

would immediately establish free

coinage of silver throughout the United

States. Making matters still worse,

Kelley soon sent the Times a long

account of the confidences in the garden,

making Bismarck furious.34

The assassin's bullet soon relieved

Garfield of further challenge by the

silver issue, but McKinley and numerous

other politicians found it wise

to maintain ambivalent bimetallism

through the decade of the eighties.

They were counseled to this course of

action by the activities of particular

persons and groups.

Ohio's free coinage ranks were bolstered

by General Adoniram Judson

Warner, a Democrat who during his three

terms (1879-81 and 1883-87)

competed with Bland in the introduction

of free coinage bills. Only one of

these passed the house and none the

senate, before 1889. McKinley's

Republican confreres, and sometimes a

few Ohio Democrats, voted with him

against free coinage bills. But they

joined the Democrats in a unanimous

Ohio "no" against suspension

of limited silver coinage.35

McKinley became increasingly an intimate

associate in his party's mone-

tary finesse. Chairman of the

resolutions committee at both the 1884 and

1888 conventions, he presented to those

gatherings the proof of committee

skill. 36 In 1884 they could hedge

easily: "We have always recommended

the best money known to the civilized

world, and we urge that an effort be

made to unite all commercial nations in

the establishment of an international

standard which shall fix for all the

relative value of gold and silver coinage."

The Democrats also felt comfortable:

"We believe in honest money, the

gold and silver coinage of the

Constitution, and a circulating medium con-

vertible into such money without loss."37

But Cleveland had boldly demanded, in

his first inaugural, repeal of the

Bland-Allison silver purchase act, and

the late eighties brought drought to

the farmers, recession to business, and

demands for free coinage from the

Farmers' Alliances, Populists, and

Union-Labor groups. In this parlous

McKINLEY'S MONETARY PROBLEMS 281

situation the unlucky Democracy in 1888

had to avoid mention of silver,

merely reaffirming "the platform

adopted by its representatives in the con-

vention of 1884." On the other

hand, McKinley and his fellow draftsmen

were free to spring to the attack. He

read to the convention these resounding

words: "The Republican party is in

favor of the use of both gold and silver

as money, and condemns the policy of the

Democratic administration in its

efforts to demonetize silver." It

was pleasant to twit the Democrats with

the fact that Cleveland blocked free

coinage.38

Whenever McKinley entered debate on the

currency he was likely to refer

to the need to keep the greenbacks

"sacred and at par"; he wished to protect

"the good financial name" of

the Republicans through maintaining a treasury

working balance above the $100,000,000

gold reserve which Sherman had

established to safeguard resumption.39

So went the decade, with the

international bimetallists and gold men

unable to halt limited silver coinage

and the free coinage men unable to

remove the limitations. McKinley and the

rest of the middle-of-the-roaders,

opposing both unlimited free coinage and

suspension of limited coinage, sat

tight. With the approach of 1890,

however, they found it necessary to

reaffirm their position in order to

protect their political status. At the same

time, in Ohio, interest was shifting

from the currency to the tariff, with both

parties enticing wool-growers, and the

iron and steel manufacturers, with

protective state planks. McKinley and

some other Republicans industriously

encouraged the shift, watchful lest

Democratic monetary propositions under-

mine the protective principle, which

they should reinforce.

The conjunction of the 1888 recession

and President Cleveland's demand

for a lower tariff appeared a godsend.

Surely high protection must bring

prosperity (incidentally meeting the

party campaign pledge) and put a

quietus on silver. The first session of

the fifty-first congress seemed a golden

opportunity, with Republicans holding

the presidency, and senate and house

(narrowly), for the first time since

1875. They had a talented triumvirate

in the house, with determined McKinley

installed in the dying Kelley's

chairmanship of the ways and means

committee, with imperious Reed as

speaker, and with wily Joe Cannon as

third member of the committee on

rules; they cooperated with the Aldrich

leadership in the senate. As the

president had no important policies

differing from those of this Republican

machine, it could function as a unit,

drawing party lines tightly.

But McKinley et al must pay toll on the

legislative highway; the minority

had warned them the price would be high.40

Friction and filibustering had

re-proved their efficacy in the previous

session, and many agrarians were

282 OHIO HISTORY

dubious of high protection. The four new

states--Montana, North and South

Dakota, and Washington--hopefully but

uncertainly admitted in November

1889 for a senate Republican majority,

favored silver producers and allied

themselves with currency expansionists.

For such reasons, party irregularity

became more common in the 1889-91

congress than at any time since the

Liberal Republican era.41 Yet

the machine maneuverers managed to push

through four important measures in 1890:

the McKinley tariff and McKinley

customs administration laws, and the

Sherman silver purchase and Sherman

antitrust laws, not to mention the

back-scratching dependent pension act. It

was a great year for Ohio.

To devise a monetary compromise which

should grease the ways for high

protection required much maneuvering--at

the White House and both ends

of the capitol. President Harrison

invited the influential Francis G. New-

lands of Nevada, vice president of the

National Executive Silver Committee,

to confer with him and with the

Republican policy makers on a suitable

"compromise."42 They

concocted a plan to attract votes of members with

silver producer, and currency

expansionist, constituencies: bullion purchases

would be expanded to cover currently

calculated output, and would be paid

for by emissions of treasury notes, thus

amplifying the currency supply--

but avoiding free coinage at sixteen to

one.

A bill pieced together along these

lines, after hectic caucuses of senate and

house members, emerged as the April 23

caucus agreement.43 But it lan-

guished in the house while McKinley et

al pushed through the house version

of high protection as a party measure--a

job completed May 21. On June 5,

after heated disputation, McKinley was

able to get house consent to a special

rule limiting amendments and debate. He

said of the leadership, "We are

after practical results." The

Republicans were doing their duty by silver,

whereas Cleveland's party had neglected

it. "For four long years . . . a

single voice, a single man, elected to

execute the laws, not to make them,

commanded the majority on that side of

the House to be silent, and they

were silent." (Applause and

laughter on the Republican side.)44

Late on Saturday afternoon, June 7,

McKinley closed the debate with

remarks calculated to reassure diverse

factions and himself (if he had

doubts). He insisted that the bill was

"the best which is attainable." "We

cannot have ideal legislation," he

said. "It is not possible. Practical men

do not expect it."45 Representative

Horace F. Bartine of Nevada complained

that eastern Republicans did not show

proper gratitude for protection votes

of western Republicans.46 But

McKinley insisted that the bill was just--just

to silver producers as furnishing a

market for their annual product; to free

McKINLEY'S MONETARY PROBLEMS 283

coinage men because they themselves

calculated that the new purchases

would raise silver's price toward parity

and then consummate free coinage;

to the guardians of "good

money" because the bullion was bought at its

market price and the silver certificates

were redeemable in gold and silver

coin and legal tender for all debts,

public and private. On that day a house

bill for limited silver coinage got

through, 135-119, with 73 paired or not

voting.47

Meanwhile, free coinage men had been

busy concocting a senate free

coinage bill, S. 2350, and collecting

fifteen Republican members to join

southern Democratic senators in amending

the house bill with a free coinage

requirement. This they accomplished June

17. Next, house silverites sought

house concurrence in the senate

amendment. But McKinley, Reed, and

Cannon were determined to get

nonconcurrence, so as to salvage their limited

coinage bill through a conference

committee. In their effort the triumvirate

overreached themselves, incurring a

majority vote against them June 21 on

their sleight-of-hand manipulation of

the record in the house journal of two

days earlier. As Cannon frankly

admitted, a majority can make the journal

"tell that which is untrue . . .

can do anything . . . can disregard the rules;

it did falsify the Journal." He

ridiculed Bland for protesting against "gag

law": "My friend is always

being gagged. Why, God knows a barrel of

ipecac would not gag him.

(Laughter.)"48

Over the ensuing weekend McKinley

recovered his self-assurance, if

indeed he ever had lost part of it, and

laughingly reminded the house of

his power, June 24. "The Republican

party having taken possession of the

Chamber again (laughter), bring this

bill back at once." He demanded

nonconcurrence, lest the United States

have to coin, free, the silver of the

entire world. His party through the past

thirty years had "given the country

the best monetary system known to the

financial world," and this measure

would "not interfere with future

international arrangements." He chose

this moment to reiterate his personal

allegiance to silver. "I would not

dishonor it; I would give it equal credit

and honor with gold. ... I would

utilize both metals as money and

discredit neither. I want the double stand-

ard, and I believe a conference will

accomplish these purposes . . . will

produce a bill satisfactory to our whole

people of every section and interest.49

Charges were rife of the pressure being

exerted for the senate free silver

measure. As Representative Abner Taylor

of Illinois complained, "it was

being pushed by the most disgraceful

lobby ever in the Capitol. Hardly a

corner outside of the hall of the House

could be turned without running

against some of them." Nevertheless

the house on June 25 voted 135-152

284 OHIO HISTORY

against the senate free coinage

amendment and then sent the bill to

conference.

What precisely happened in the

conference is unclear. Sherman, who

headed it, reported briefly on its

action in his Recollections four years later;

but he refused to tell the senate what

the conferees said to each other,

alleging that it would be a

"departure" from "gentlemanly propriety" to

disclose private conversation indicating

"the means by which we got

together." Their refusal aggravated

Senator John T. Morgan of Alabama,

who tartly reminded Sherman, "Oh,

Senators are not in that sense gentlemen

in the conference-room. They are

Senators." To which Sherman replied,

"But they are expected to be

gentlemen."50 (Herein Sherman divulged one

reason why the Congressional Record often

frustrates inquisitive historians

and biographers.)

Thuswise did the Sherman silver purchase

act reach the statute books

July 14, 1890, a testimonial to

ambivalent bimetallism. McKinley et al had

unwittingly guaranteed future trouble

for the nation's gold reserve. The

conference compromise required the

treasury to buy 4,500,000 ounces of

silver bullion monthly at the market price,

paying for it with treasury notes

redeemable in gold or silver coin at the

"discretion" of the secretary of the

treasury; but the act also declared it

to be United States policy to maintain

gold and silver on a parity, wording

which the treasury interpreted as a

virtual pledge to redeem in gold. The

potential strain on the treasury was

thought lessened, however, by the

stipulation (credited to Sherman) for

purchasing by ounces; it seemed

that if the price fell (which before long

it did) the treasury would save money.

The worried Sherman regretted the

4,500,000 ounce requirement, as

something above actual current

production; and he openly declared he

voted for the measure only to forestall

free coinage. As events transpired,

the act produced fresh issues of the

legal tender treasury notes amounting to

$24,000,000 in 1890, $53,000,000 in

1891, $47,000,000 in 1892, and

$24,000,000 in the first half of 1893.

But possibilities of gold strain roused

no concern in the breasts of the

drafters of the Ohio state Republican plat-

form in 1890. Endorsing the Harrison

administration, they added, "We

also fully approve the wise action of

the Republican members of both

houses of Congress in fulfilling the

pledges of the party in legislation upon

the coinage of silver," and upon

the tariff, pensions, and so forth.51 Not so

the majority of McKinley's constituents

that November. They unreasonably

rewarded his efforts with retirement.

McKinley's defeat was a blessing. It

helped to keep his path toward the

presidency relatively free of monetary

obstructions prior to 1896. Absence

|

|

|

from Washington following March 4, 1891, freed him from possible embar- rassments over house defeat of a sequence of free coinage bills and over congressional yielding in 1893 to Cleveland's adamant demand for repeal of the Sherman silver purchase act--a repeal obtained to stem the drain on the gold reserve. The 1892 Republican convention, of which McKinley was permanent chairman, adopted a monetary plank expressing perfectly his own ambivalent bimetallism: support of the use of gold and silver "with such restrictions" as would maintain their parity of value, and endorsement of an international conference to secure such parity worldwide.52 This satisfied at least a plurality of voters in Ohio, where free coinage groups were badly split, and Sherman decided a majority of both parties in the state opposed free coinage. McKinley, unburdened with any responsi- |

McKINLEY'S MONETARY PROBLEMS 287

bility for devising concrete policy,

used cloudy monetary comments on the

stump, telling audiences that silver

must not be "discriminated against"; it

must have "justice." The

Republicans meanwhile were so vigorously build-

ing up protectionist sentiment that they

were able to turn the tables and

secure for McKinley handsome majorities

in the gubernatorial elections of

1891 and 1893. His second victory was

not unconnected with the well-

known fact of his own straightened

circumstances due to a depression mishap,

which identified him further with common

folk.53

By the close of his second governorship

(January 1896) McKinley's candi-

dacy for the presidential nomination had

been well launched by Mark Hanna,

helped by the expert vagueness of the

protege. Until he was very close to

convention time, he refused Hanna's

urging that he stand on the gold stand-

ard, firmly insisting that he stood on

his record. This policy won him

endorsement by western silverites and by

the Ohio Republican convention,

which in March obliged nicely with a

high-tariff-bimetallic platform. Also,

the policy gave Hanna a bargaining

weapon for the coming convention, where

he could fake reluctance to accept a

gold plank which, when consented to,

would afford eastern supporters of Reed

and other McKinley opponents a

solacing sense of quasi-victory,

assuaging defeat of their candidates.54

However, during the interval between January

and June, McKinley's

opponents made such capital of his

silver uncertainties that under a less

able tactician than Hanna the Canton

"sphinx" might have been covered by

sands shifting in favor of Reed of Maine

or Allison of Iowa.55 Actually, a

few publicists and economists had been

calling attention to the fact that world

gold production had been rising since

1887 and was likely to continue

(because of South African developments)

into a rising price level, which

would alleviate some of the distress that

free silver was claimed to cure.

There is no reason to suppose that

McKinley had studied these analyses, but

his faith in the tariff panacea, on

which he had hoped to run, and his earlier

success with bimetallic utterances

inspired his silence on money.

Immanence of the convention forced him

to take advice and exercise his

skill at shaded meanings.56 He

realized that he must endorse the existing

standard, which was gold. The right of

free and unlimited silver coinage

had ended in 1873 and the policy of limited

coinage, implemented under

the laws of 1878 and 1890, had been

discarded by the repeal of 1893.

Yet he, and many other Republican

fence-sitters, had repeatedly done

obeisance to "bimetallism."

Also, the magic word had aided repeal of the

Sherman purchase act, in a closing

clause of that measure calling on the

government for steady efforts to

establish "a safe system of bimetallism."

`

288 OHIO HISTORY

Many Republican candidates--even some in

the East--wanted to be able

to use the term in 1896.

Therefore, McKinley's plank as carried

to St. Louis in the pockets of

Hanna and Foraker, sought to make his

retreat from ambivalent bimetallism

as conciliatory as possible. He used

familiar verbiage: his party stood for

sound money, the fullest use of silver

consistent with parity with gold, and

an international bimetallic agreement to

maintain that parity. To these

mellifluous phrasings he added that his

party opposed free and unlimited

silver coinage because it had become

"the plain duty of the United States

to maintain our present standard."57

But what was the "present" standard?

The re-drafters at St. Louis insisted

on less conciliatory wording, although

not averse to some sweetening. So,

in the final version they based their

argument on honesty, domestic good

faith, and international repute. The

party stood for "sound money," every

dollar "as good as gold,"

unimpaired credit, and "inviolable obligations"

in line with "the most enlightened

nations of the earth." "We are therefore

opposed to the free coinage of silver,

except by international agreement with

the leading commercial nations of the

earth, which agreement we pledge

ourselves to promote, and until such

agreement can be obtained the existing

gold standard must be maintained."

The fat was in the fire--as that old

Republican Nestor from Colorado had

warned them it would be. Teller et al

walked out. But numerous less

intransigent Republicans with silver

producer or cheap money constitu-

encies stayed, clinging to an uncertain

future for international bimetallism

and for themselves. Among these, there

soon was some little rivalry for the

"credit" for inserting,

"which agreement we pledge ourselves to promote."58

But their credit rivalry was nothing

compared with ardent authorship of the

word "gold," claims highly

vocal after it began to appear that the word

was more of an asset than a liability.

This precious convention "victory"

was claimed by some dozen voices rising

from New York to Wisconsin,

bequeathing an historical controversy to

the next half century. Of course

the efforts of no individual could be

completely separable from activities

of others.59

Gold was hard for McKinley to pronounce,

but by July he felt emboldened

to utter the word on his front porch and

early in August he thought the

silver craze would not go higher. His

acceptance speech, of August 26,

astutely coupled this "good

money" with the financial welfare of laborers,

producers, and common folk, no less than

businessmen and financiers. Again

he pledged promotion of international

bimetallism. Prosperity would return

|

|

|

with wise protection.60 In September some eastern campaigners found they now could drop mention of bimetallism. By November the well-heeled propaganda techniques of Hanna's cohorts, industrial blackmail, crop scarci- ties abroad, rising farm prices at home, and numerous other more subtle factors brought defeat of the free coinage forces and victory to McKinley."61 The president-elect nevertheless felt bound to "do something" for silver, and for those silver Republicans who had not left the party, especially as this might expedite delicate senate arrangements for tariff increases in the special session he was to convene. So Senators George F. Hoar of Massa- chusetts, William E. Chandler of New Hampshire, John H. Gear of Iowa, |

|

|

|

and Thomas H. Carter of Montana-a transcontinental aggregation-- arranged with McKinley for Senator Edward 0. Wolcott of Colorado to test the international bimetallic waters in Europe, looking to a plunge into them. They optimistically assured McKinley "the favorable feeling is great in France, is strong in Germany and is powerfully affecting leading statesmen in England."62 McKinley was happy to credit their news. Wolcott conferred through January and February in London, Berlin, and Paris (where reciprocal cooperation between bimetallism and duties on French exports to the United States was explored), and Chandler put through congress on March 3 an |

McKINLEY'S MONETARY PROBLEMS 291

appropriation of $100,000 for financing

United States participation in

another international bimetallic

conference, should the president find the

time propitious. The senator had assured

the incoming president that such

legislation would lessen the hazards for

tariff legislation.

The next day McKinley's inaugural

pledged that international bimetal-

lism would "have early and earnest

attention," and he recommended also

a United States bipartisan commission of

businessmen and politicians to

take monetary problems out of the

political arena.63 Mid-March found him

formulating, for use abroad,

instructions with "a certain vagueness," which

John Hay presumed was

"intentional," and one month later he appointed

Wolcott, Charles J. Paine (a Boston

capitalist), and ex-vice president

Adlai E. Stevenson as peripatetic

emissaries in search of a conference.

While they sought in vain, German and

French exporters found unpleasing

the tariff emerging at Washington. There

silver senators held the majority

in the senate finance committee, and

enjoyed enough power in the senate

as a whole to make things mildly unpleasant

for a less-well-assured man

than McKinley.

They unkindly taunted him with his

earlier pro-silver votes, questioned

his loyalty to the Wolcott mission, and

criticized his choice of the gold

standard advocate, Lyman J. Gage, as

secretary of the treasury. As

McKinley espoused bond payments in gold,

they pressed through the senate

a Teller resolution for redemption of

bonds "at the option of the Govern-

ment in silver dollars"--a

proposition supported by neither of Ohio's sena-

tors and by only six of her twenty-one

representatives, of whom but one

lasted in congress thereafter as long as

March 1903. Their high point of

1898 was a rider to the war revenue act

of June 13, directing the secretary

of the treasury to coin into standard

silver dollars all the bullion remaining

in the treasury from the Sherman silver

purchase act, at a rate of not less

than $1,500,000 monthly. But business

was too active to make this measure

inflationary.64

Unperturbed, McKinley pursued his even

way on the hustings that fall,

boasting of gold accumulations, and

denouncing "any demoralization of

our currency." He celebrated

November Republican winnings with an

annual message reiterating an 1897

request that United States notes, once

redeemed in gold, be paid out again only

for gold; and he bespoke immedi-

ate legislation to erect a gold trust

fund for redemption of greenbacks.65

Time was running out on bimetallism in

1899--thanks to South Africa,

Australia, the Yukon, a new cyanide

process for extracting gold, and heavy

farm exports to crop-disappointed

Europe. Gold production in 1898 had

292 OHIO HISTORY

been two and one-half times that of 1890

and congressional elections had

diluted Republican silver strength. Per

capita circulation was up and so

was the price level, slightly. McKinley

basked in the effulgence of what

he interpreted as protection prosperity;

the former bimetallist in the fall

of 1899 descanted to middlewestern

audiences on the favorable balance of

trade which "comes to us in

gold."66

So McKinley and Gage greeted the first

session of the fifty-sixth congress

with a clarion call: "to make

adequate provision to insure the maintenance

of the gold standard" congress

should enlarge the power and the mandate

to the secretary of the treasury to buy

gold with long and short term bonds,

at lower rates of interest, to forestall

any future drain on the gold supply;

thus, would the parity in value of gold

and silver coins be maintained.

Congress obliged. H.R. 1 got through the

house December 19. But nearly

three months elapsed before its

enactment into law, giving more time for

wandering silver sheep to seek the path

back to the Republican fold. Teller

grew less denunciatory than of yore, and

Wolcott reported that people out

West grew less pessimistic about life.67

Yet some concession to surviving

bimetallists must be made, and so the

act of March 14, 1900, carried a faint

odor of the bimetallism of McKinley's

political youth.

On the one hand, the law acknowledged

the long-existing fact that the gold

dollar was the standard unit of value.

All forms of United States money

must be maintained at parity with the

gold dollar; and to insure prompt

gold redemption of greenbacks and 1890

treasury notes, the treasury must

set apart a reserve fund of $150,000,000

in gold coin and bullion and the

redeemed notes must not be reissued

except for gold.

On the other hand, the law gave solemn

assurance that the legal tender

quality of any money coined or issued by

the United States was retained.

Also, "the provisions of this Act

are not intended to preclude the accomplish-

ment of international bimetallism

whenever conditions shall make it expe-

dient and practical to secure the same

by concurrent action of the leading

commercial nations of the world and at a

ratio which shall insure permanence

of relative value between gold and

silver."68

McKinley could sign this act without

qualms; and he could applaud the

1900 Republican plank, "We renew

our allegiance to the principle of the

gold standard and declare our confidence

in the wisdom of the legislation

of the Fifty-sixth Congress."69

On silver he had come full circle.

THE AUTHOR: Jeannette P. Nichols for-

merly was associate professor of history

and

chairman of the Graduate Group in

Economic

History at the University of

Pennsylvania, and

now is research associate in economic

history.