Ohio History Journal

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS EARLY OHIO PAINTERS: CINCINNATI, 1830-1850 by DONALD R. MacKENZIE |

|

WHEN AN 1840 editor of the New York Star wrote, "Cincinnati! What is there in the atmosphere of Cincinnati, that has so thoroughly awakened the arts of sculpture and painting?" he was expressing an out- sider's appraisal of the Queen City. The famous Mrs. Trollope, after three years in Cincinnati, had come nearer the truth with her observation on the indigenous American artist: With regard to the fine arts, their paintings, I think, are quite as good, or rather better, than might be ex- pected from the patronage they re- ceive; the wonder is that any man can be found with courage enough to devote himself to a profession in which he has so little chance of find- ing a maintenance. The trade of a carpenter opens an infinitely better prospect; and this is so well known, that nothing but a genuine passion for the art could beguile any one to pur- sue it.2 Despite economic insecurity, more than sixty painters joined the ranks of prac- ticing artists in Cincinnati between 1830 and 1850. Some of these artists, notably NOTES ARE ON PAGES 131-132 |

|

|

|

Thomas Worthington Whittredge and Wil- liam H. Powell, achieved reputations still nationally recognized today. Many other painters, such as Abraham G. D. Tuthill, James H. Beard, John P. Frankenstein, Lilly Martin Spencer, and Joseph Oriel Eaton, then commanded higher fees and were equally important, but are now rele- gated to near-obscurity. Changes in taste and lack of information about these art- ists and their works have led to their obliv- ion. Also, their inclination to travel around the country (and abroad, when financially possible) tended to scatter their better works and prevent true evaluation of their abilities. Taken as a group these artists repre- sent the greatest disparity in professional training and experience. Tuthill, an in- veterate wanderer, remained in Cincinnati longer than in most cities that he visited. As a young man he had studied with Ben- jamin West in London; and later he had spent a year in Paris. When he arrived in the Queen City in 1830, he was a thirty- year veteran of portrait painting in the northeastern states and Detroit. On the other hand, James H. Beard, who arrived the same year, was only nineteen years old. His training consisted of four lessons |

|

112

OHIO HISTORY |

|

from the itinerant artist Jarvis Hanks and two years experience as a traveling limner in northeastern Ohio and western Penn- sylvania. Beard progressed rapidly in Cin- cinnati, learning through the study of paintings by other artists. Only five years later his work elicited praise from Har- riet Martineau during her visit to the United States. In her book she stated that she liked his work better than that of any other American artist.3 Twenty-five years later Beard's reputation was so well es- tablished that Henry Tuckerman wrote: "Many adherents in the South-west still hold to him, and will have their portraits by no other hand."4 Despite Beard's repu- tation in portraiture he first attracted at- tention by his ability to paint animals and children. On occasion he also depicted genre, landscape, and literary subjects, this broad range making him equally fa- mous in eastern cities. Ranking next to Beard and considered "pre-eminent" in painting and sculpture by most contemporaneous writers, John P. Frankenstein achieved artistic success be- fore he was twenty.5 In 1832 at age fif- teen he began painting portraits in Cin- cinnati, meanwhile studying anatomy at the Ohio Medical College.6 A few years later he studied sculpture with Hiram Powers, who was soon to become a world- famous artist. Frankenstein developed rapidly both as a portrait painter and as a sculptor. Although he established a studio in Philadelphia in 1834, he fre- quently visited Cincinnati during the next ten years. Unfortunately, his high-strung temperament alienated many clients, and as his career suffered, he developed a feeling of being unappreciated. In conse- quence, his influence in Cincinnati's art affairs diminished, and he withdrew more and more from society. Many years later Frankenstein bitterly attacked Nicholas Longworth and other Cincinnati patrons in a satirical booklet entitled American Art: Its Awful Altitude. A Satire.7 John Frankenstein's younger brother Godfrey also was a gifted artist. At thir- teen, Godfrey had begun painting signs in the Queen City and, when nineteen, had opened his own portrait studio.8 His industry and talent resulted in his becom- ing a leader among the younger artists |

|

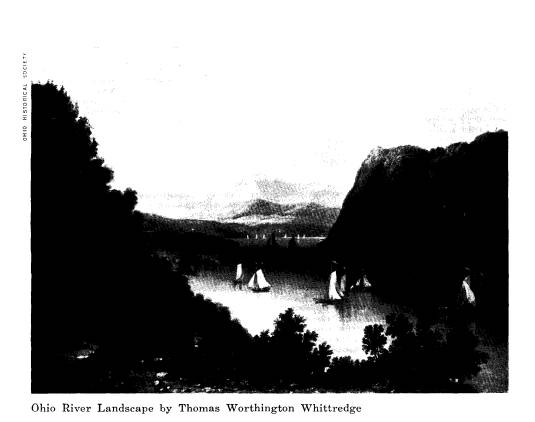

of the city. He was one of the founders, with John Whetstone, of the second Cin- cinnati Academy of Fine Arts in 1838 and, in 1840, succeeded Whetstone as its presi- dent.9 Although he painted many por- traits, including one of William Cullen Bryant, Godfrey Frankenstein delighted in landscape painting. After a first visit to Niagara in 1844, he painted more than one hundred careful studies of the river and the falls during the next twenty years.10 Many of these works were used as references in his "Panorama of the Ni- agara," which enjoyed a successful tour of the country in 1853-54. Godfrey also made several visits to the White Moun- tains but most frequently painted the scenery around Cincinnati and Spring- field. Godfrey was one of the few artists who chose to remain in Cincinnati after achieving more than a local reputation. Other artists of lesser fame who came to Cincinnati between the years 1830 and 1840 include Daniel Steele, E. Hall Mar- tin, John Crossman, Benjamin Harriman, Joseph Maggini, John J. Tucker, Sidney S. Lyon, John Caspar Wild, Philip Young, William B. Brannan, Gerhard Mueller, Samuel S. Walker, E. P. Cranch, John L. Leslie, Peyton Symmes, Thomas Campbell, and Clement R. Edwards. George Winter was active in Cincinnati in 1836 and 1837 before moving further westward to Indi- ana, where he painted portraits and many scenes of Indian life.11 Horace Harding, younger brother of the famous Chester Harding, established himself in the city before 1834 and worked there intermit- tently through 1850. Jared B. Flagg, also a member of a famous painting family, and brother of George W. Flagg, painted portraits in Cincinnati in 1840 and 1841.12 Henry Kirke Brown, later famous as a sculptor, started as a portrait painter in Cincinnati in 1836.13 Interestingly enough he, together with James Beard, was instru- mental in helping Worthington Whittredge make his start as an artist. The career of Thomas Worthington Whittredge was marked by slow, steady progress, eventually leading to the presi- dency of the National Academy of Design in 1865.14 Whittredge had begun in Cin- cinnati by trying house painting, sign painting, and daguerreotypy without suc- |

|

cess.15 In 1837 he took up portrait paint- ing, aided by Henry K. Brown and James H. Beard, both of whom were still strug- gling for professional recognition. He exhibited three landscapes in the Cincin- nati Academy exhibition of 1839 and was included in the list of artists. In addition, his name appeared in the academy's cata- log as "superintendent," a position akin to doorkeeper.16 During the next two years Whittredge took advantage of the fine private collec- tions of paintings in the city to study recognized landscape artists. In the acad- emy exhibition of 1841 his seven landscape and genre scenes all bore the label "copy."17 Whittredge was very interested in the new Daguerre process of photography then being introduced in this country. He moved to Indianapolis in 1842 and opened a da- guerreotype studio, but illness and poor economic conditions caused his business to to fail. Henry Ward Beecher, an old friend, rescued him and nursed him back to health. In appreciation, Whittredge paint- ed portraits of the Beecher family.18 He continued painting portraits in Indian- apolis until all demands were met, then |

|

returned to Cincinnati in the summer of 1843. Thereafter, he devoted himself more and more to his landscape paintings, which steadily increased in popularity, until his departure for Europe in 1849. Earlier Whittredge had had to paint portraits be- cause landscapes would not sell; now a new market had opened. Institutions called "art unions" had been organized in major cities to stimulate the exhibition and sale of paintings by Ameri- can artists. Prior to the founding in 1839 of the Apollo Association of New York (the original name of the American Art- Union), there were no established means for selling objects of art to the general public. Furthermore, the public showed very little interest in undertaking such expensive purchases. Ten years later, at the peak of its operation, the American Art-Union alone had an organization of nearly nineteen thousand subscribers par- ticipating in their annual distribution of American paintings and prints. Signifi- cantly, the second art union in the United States, the Western Art Union, was es- tablished in Cincinnati in 1847.19 All of the art unions operated similarly. Shares were sold annually to subscribers |

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS 115 |

|

for a fixed sum, usually about five dollars each. The money collected was used to produce a quality engraving of a famous painting, a print of which went to each shareholder. The balance of the funds, after expenses, went to purchase original works of art selected by a committee and distributed by lot among the subscribers. Each subscriber thus received the value of his investment in the form of a fine reproduction, plus an opportunity to win an original painting. Notices were issued periodically to in- form subscribers of paintings purchased and membership enrollments. Gradually these notices expanded from brief listings of the paintings into monthly art periodi- cals containing articles on artists and aesthetics, exhibition reviews, and news of artists abroad. Since native subjects of American life and landscape were con- tinuously deemed most desirable by the selection committees, the publications were very influential in creating the taste of art union subscribers. People looked with new eyes as the artists brought the coun- tryside into focus. The increasing popularity of landscape and American genre painting during the period 1840 to 1860 was reflected in the Cincinnati directories and the listing of artists by such writers as Charles Cist. Where once the title "portrait painter" had precedence, terms such as "landscape," "marine," and "historical painter," now became predominant. Nonetheless, nearly every painter could produce a portrait when the opportunity offered. For most artists in the West this was economic necessity. Outstanding among these more versatile painters was William Henry Powell, who, through the philanthropy of Nicholas Longworth, had been able to study in the East. Although he suffered from poor health and financial problems during his early career, in 1847 his success was con- firmed by the commission from congress to paint the remaining panel in the capi- tol rotunda at Washington. His historic painting "Battle of Lake Erie," commis- sioned for the capitol at Columbus, also brought him much fame.20 One of Powell's contemporaries, the poet-painter Thomas Buchanan Read, ri- |

|

valed Powell in his quick rise to fame. Read arrived in Cincinnati in 1837 after a succession of jobs: rolling cigars, paint- ing signs, acting, and carving tomb- stones.21 Read's portrait painting soon caught the eye of Nicholas Longworth, who assisted him financially in his art training and later helped him establish a studio in New York City. Like most western artists, Read first achieved his local reputation in portraiture; later he became known for historical painting based on literary themes. Simultaneously with his development as a painter, Read aspired to lecome a poet and conscientiously gave equal time to that pursuit. His efforts were well re- ceived. By 1846, when he moved to Phila- delphia, he was professionally recognized in both fields, his reputation as a poet overshadowing his fame as a painter.22 Many volumes of his poems were pub- lished, the best known of these being "Sheridan's Ride." Successful women painters were com- paratively scarce in the United States in the nineteenth century, but Cincinnati could boast of two in the same decade, Sophie Gengembre and Lilly Martin Spencer. Both were born in France and both immigrated with their families to Ohio. Although Sophie Gengembre never achieved the national reputation of Lilly Martin Spencer, she painted many por- traits of Cincinnatians and enjoyed an excellent local reputation. Lilly Martin, born Angelique Marie Mar- tin, had shown considerable natural tal- ent as a child and had been encouraged by her father and the Marietta artist Charles Sullivan. Only nineteen when she arrived in Cincinnati in 1841, she was already a prodigious painter.23 In No- vember of that year, shortly after her ar- rival, she had a public exhibition of her works and the following year showed six paintings in the second exhibition of the Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge. She refused Nicholas Long- worth's offer to finance her in studying and copying the old masters abroad be- cause he stipulated that she could do no original painting during the trip. In a letter to her mother in 1842, Lilly ex- plained her purpose and philosophy. "I |

|

want to try," she wrote, "to make all my painting have a tendency towards morall [sic] improvement as far as it is in the power of painting, speaking from those who are good and virtuous, to counteract evil."24 Her favorite subjects were family genre involving the very young or the very old and characters from Shake- speare. After Lilly's marriage to Spencer and the arrival of their first child in 1846, she resumed painting with continuing success. Nine of her paintings were displayed in |

|

the initial exhibition of the Western Art Union in 1847, and four later paintings were purchased by the union for distri- bution. That same year, the Spencer fam- ily moved to New York. There the Ameri- can Art-Union purchased two of her pic- tures in 1848, two more in 1849, and four in 1851. Her painting "Life's Happy Hours" was selected by the Western Art Union as their engraving for the year 1849. In May 1850 she was elected an honorary member of the National Acad- emy, certainly gratifying recognition for |

|

an artist of twenty-eight who had painted professionally for only nine years.25 Many other artists benefited financially and professionally from the new interest in art created by the art unions, but por- traits continued to be in demand. Among the more successful painters active in Cin- cinnati in the decade 1840-50 were Minor K. Kellogg, John Cranch, Charles Soule, Sr., B. W. Jenks, John R. Johnson, Jacob Cox, Donald McNaughton, William Wal- cutt, Jeff Wright, William Bingham, M. |

|

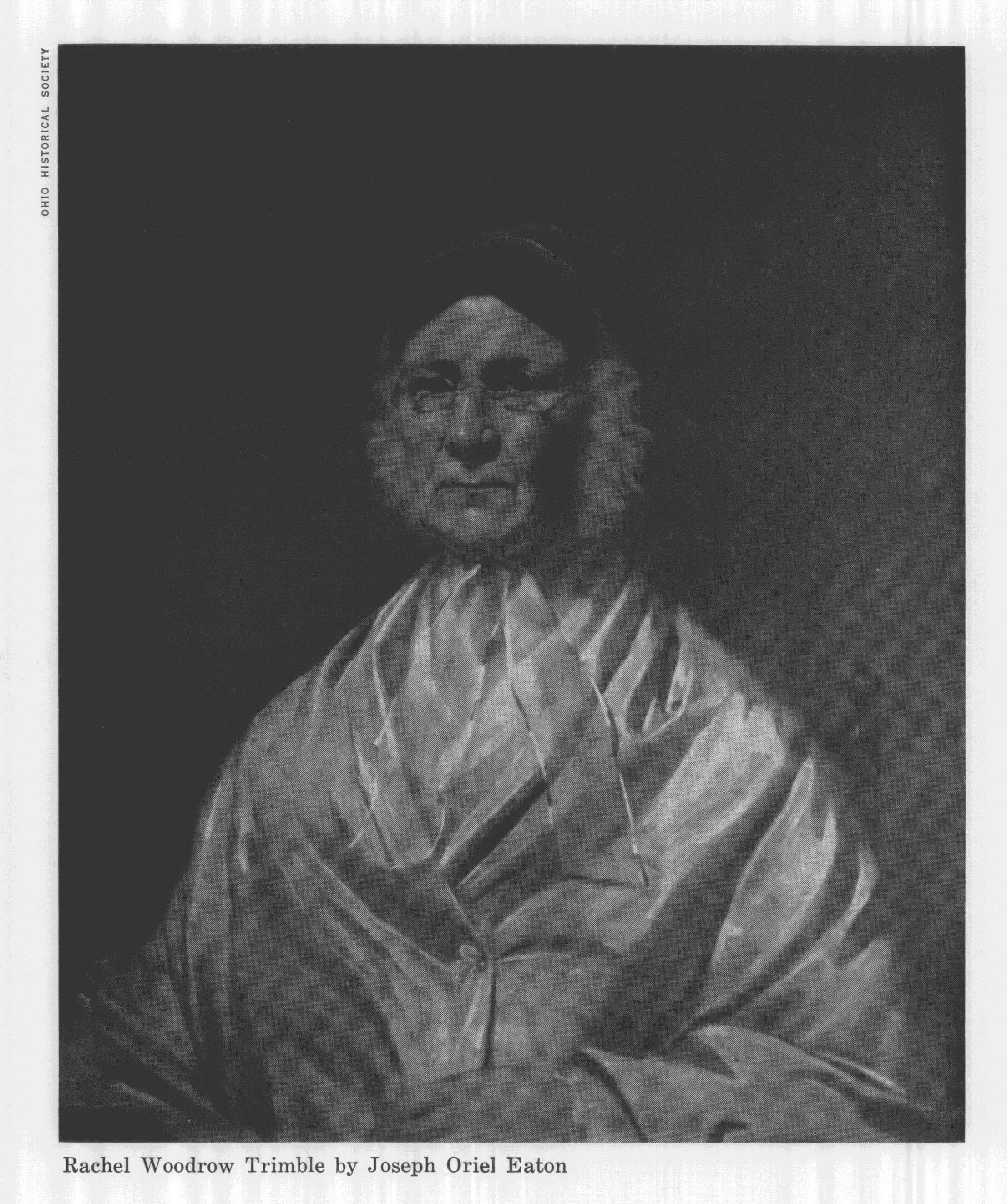

W. Hopkins, Charles A. Vaughan, David E. Walcutt, Trevor Fowler, Van Stavoren, George W. Phillips, A. H. Hammell, George W. White, Charles Edward Crid- land, Peyton C. Wyeth, and C. G. Miller. Two artists who enjoyed exceptional success were John Insco Williams and Joseph Oriel Eaton. Both were born in Ohio, became itinerant portrait painters in Indiana, and eventually settled in Cin- cinnati. Williams had been apprenticed as a youth to an uncle in Richmond, Indi- |

|

118

OHIO HISTORY |

|

ana, to learn house and carriage painting, but after taking a few art lessons in Cin- cinnati, he became an itinerant artist in central Indiana. In 1836 he began three years of study at the Pennsylvania Acad- emy of Fine Arts with Thomas Sully and Russell Smith. Although known today primarily as a portrait painter, his two large Biblical panoramas of the creation and the fall of man were very famous in the East as well as the West. Joseph Oriel Eaton ran away from his Newark home at seventeen to become an itinerant painter in Indiana. He was aided and encouraged by Jacob Cox, a local art- ist in Indianapolis, and according to the Indiana State Sentinel of December 6, 1845, he was then painting "admirable likenesses of a few who have taste enough to appreciate genius, and faces of which they are not ashamed." In 1846 Eaton moved to Cincinnati, where he came in contact with James Beard, Thomas Buchanan Read, and Worthington Whittredge. His reputation for portraiture grew rapidly. Jacob Cox later said that in seventeen years in Cin- cinnati, Eaton "made by his own brush $50,000 and was the most popular and best portrait painter there."z6 Henry A. |

|

Ford, writing the history of the Queen City only six years after Eaton's death, put him down as one of the most famous portrait painters in the country.27 More- over, Eaton painted many landscapes of Ohio and the northeastern states. Both Eaton and Williams found the Cincinnati market for portrait commis- sions quite competitive. Nonetheless, the patronage and interest in painting created by the Western Art Union provided a very favorable climate for art. At mid- century Cincinnati was unquestionably the cultural center of the region, and was referred to, aptly enough, as the Paris of the West. Editor Henry Ratterman, com- menting on local art activities some years later, described the role of the Queen City when he wrote: During this period art evinced more life, more vitality, more self-reliance, in Cincinnati than at any other period. . . .Our city was generally the start- ing point of American artists. We gave them birth and nourishment in their infancy; and when our artists were grown to manhood, then the east would come to woo and wed them, and toast of them as their own.28 THE AUTHOR: Donald

R. MacKenzie is chairman of the department of art at the College of Wooster. This is the second in a series of articles he has written on early Ohio painters that is based on the painting collection at the Ohio Historical Society. The first article, "The Itinerant Artist in Early Ohio," appeared in the Winter 1964 issue. |