Ohio History Journal

|

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE HARDING PAPERS

by DONALD E. PITZER

April 25, 1964, marked the beginning of an opportunity for a new perspec- tive in telling the story of the life and times of Warren G. Harding. On that date The Ohio Historical Society opened to the public a collection of Harding papers which it had received in the preceding six months from the Harding Memorial Association at Marion, Ohio.1 Material never before available for scholarly research thus began to shed a clearer light upon Harding and the variously-interpreted age of the 1920's.2 The latter has been characterized as one so misunderstood that historians "cannot as yet distinguish between the important and the unimportant."3 Already, the Harding Papers have yielded significant information for scores of individuals preparing theses, dissertations, biographies, and general histories of the period.4 The ultimate value of the insights into and possible reassessments

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 182-183 |

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE HARDING

PAPERS 77

of Harding and his era gained through

such use of the papers, however,

will stand in direct proportion to the

nature and extent of the collection

itself.

Through a set of unique circumstances

the Harding Papers have become

a part of the archives of The Ohio

Historical Society library. It is insufficient

to suggest their worth merely by stating

the fact that they bulk to an

imposing 350,000 sheets filling over

eight hundred manuscript boxes. Early

in 1924, not more than six months after

the death of her husband, Mrs.

Harding cast a continuing shadow over

the papers by giving credence to

the idea that she had destroyed all of

them. In that year during a visit to

Washington, D. C., she told Dr. Charles

Moore, who had solicited the

contents of the President's files for

the Library of Congress, and Frank N.

Doubleday, who wanted to publish a

volume of Harding's letters, that she

had burned them in order to protect his

memory.5 In reality, she had sorted

through only certain segments of the

total collection and had preserved

much of what she had seen. Before she

died the following November, she

had willed all of the remaining

correspondence in her possession to the

newly-founded Harding Memorial

Association. Nevertheless, the myth that

no material worth a scholar's time had

survived her determined purge lived

on. Allen Nevins' sketch of the life of

Harding in the Dictionary of American

Biography in 1932 both illustrated the persistence of the rumor

and also

solidified it for the next generation by

asserting that part of the reason

no biography of the twenty-ninth

president had appeared was because "Mrs.

Harding before her death destroyed his

papers."6

Although the Harding Papers as they now

exist may never be completely

free from the stigma that becomes

attached to any set of documents which

has been purposefully censored, it is

felt that a knowledge of the sections

of the collection to which Mrs. Harding

did and did not have access and

an understanding of the basic character

and contents of all of the materials

that have been preserved should help to

clear the air for an objective

appreciation of their historical value.

When President Harding died in San

Francisco on August 2, 1923, his public

and private correspondence was in

four definable divisions located in his

offices in Marion, Ohio and Washing-

ton, D. C.7 The record of his

three decades as a Marion businessman and of

his two decades as an Ohio politician

before being elected to the United

States Senate in 1914 lay in the files

of the Marion Star newspaper office.

Most of the material from his six United

States senatorial years and from

his campaign for the presidency in 1920

was in the care of his long-time

private secretary, George B. Christian,

Jr., and was stored either at the

latter's Washington, D. C., home or at

the White House. The last two

groups of papers were in the Executive

Mansion. The official correspondence

of the Harding Administration was kept

in the Executive Wing office. Letters

to and from the President that were

considered to be of special importance

or of a private, personal nature were

filed in his private office on the

second floor.8

78 OHIO HISTORY

Mrs. Harding evidenced a desire to

screen all of her deceased husband's

papers, but succeeded in gaining control

of only two sections of them --

the collections in the private office of

the White House and in the Marion

Star office.9 For several days before she left

the White House for the last

time on August 17, 1923, she directed

the packing of her own and the

late President's belongings for shipment

to Marion. Assisted by the former

military aide to the President, Major

Ora M. Baldinger, she sorted through

the contents of the desk, safe and files

of the private office, committing

certain items to the blazing fireplace

as she did so. The private papers that

remained were put into six to eight

boxes that measured ten feet long, a

foot wide, and a foot deep and were sent

to the Marion offices, where the

widow could screen them further at her

leisure.

During the six weeks of late September

and October 1923, the former

first lady completed her mission of

destroying certain sections of the

Harding Papers. Her objective seems to

have been the eradication of any

evidence that might have cast an

accusing finger toward her husband when

news of the scandals that had taken

place during his presidency became

common knowledge. By the time her work

was finished, the size of the

White House private office collection

was reduced by about sixty percent,

so that it fitted snugly into two

ten-foot-long boxes. Since the files in the

Star office were available to Mrs. Harding during these days

of sorting and

burning, they also must have come under

some censorship.10 Yet, judging

from the fact that the present

collection of material from this source shows

few, if any, of the telltale gaps which

undoubtedly would have resulted if

she had destroyed any significant parts

of it, it can be assumed that the

files in the newspaper office were

virtually untouched.

In 1925 an event occurred which has made

it possible to isolate the material

in the present Harding collection which

was originally in the White House

private office group but passed

unscathed through Mrs. Harding's hands

into the care of the Harding Memorial

Association. In that year the

Association permitted editor John Van

Bibber from the Doubleday, Page

Company to have copies made of over five

thousand pieces of this corre-

spondence preliminary to publication.11

The proposed volume of letters

never appeared, but the typed copies12

(and their three carbons)13 were

kept with the Harding Papers and now

identify the letters in the collection

from which they were copied as ones from

the White House private office

files. About twenty manuscript boxes

full of this material, much of it

stamped "P.P.F." (private,

personal file), have been identified.14

While the two divisions of Harding's

papers that had undergone his

widow's screening remained under lock

and key in the possession of the

Memorial Association, the two with which

she had not tampered began to

gravitate toward the same depository.

The job of packing the official papers

from the White House Executive Wing

files after the President's death fell

to his trusted secretary, George B.

Christian, Jr. Once Christian had finished,

however, he did not have them shipped to

Marion for Mrs. Harding's perusal

in compliance with her instructions.l5

Instead, he had them stored in the

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE HARDING

PAPERS 79

cellar of the White House. There this

one hundred cubic feet of papers

remained practically forgotten until its

discovery by workmen in 1929.16

At that time it was the fond hope of the

director of the manuscript division

of the Library of Congress, Dr. J.

Franklin Jameson, that this new find could

be secured for that institution and

opened for historical research; instead, it

had to be sent to the Memorial

Association at Marion, according to the

provisions of Mrs. Harding's will.

The last section of the Harding Papers

was still in Christian's hands.

It contained at least two voluminous

divisions of material. In the first were

the senatorial papers that had

accumulated in Harding's Washington office

from 1915 to 1921. In the second was the

contents of a ten-box shipment

of the forty-three drawers of senatorial

and presidential election correspond-

ence which had been handled at the

Marion campaign headquarters in 1920

and which had been sent to Christian at

the capital just prior to Harding's

inauguration.17 In 1934, ten

years after Mrs. Harding's death and five years

after the discovery of the Executive

Wing collection in the basement of

the White House, the former presidential

secretary decided to give some

of his holdings to the Library of

Congress. On December 27, 1934, he donated

seven large and three small boxes of

material from his collection. Eight of

the boxes contained the official

presidential campaign correspondence filed

by states,18 recommendations

for appointments, and congratulatory mes-

sages.19 The other two were

filled with personal correspondence.20 Sometime

before May 1935, Christian made a second

contribution to the Library of

Congress. This time it was eighteen

letter-file cases of the senatorial and

election campaign material from the

Marion campaign headquarters.21 At

the insistence of the officials of the

Harding Memorial Association, however,

all of the Library of Congress

acquisitions from Christian were forwarded to

Marion on May 4, 1935, and stored in the

basement of the Harding home.

With the exception of the extremely

valuable senatorial papers from the

1915 to 1920 period with which Christian

had not chosen to part in 1935,

the Memorial Association collection had

reached its full dimensions. The

cautious secretary, who at one time

intended to write a definitive Harding

biography based in part upon the papers

in his own possession,22 bound

most of the remaining senatorial papers

in folders of the United States

Shipping Board with which he was

associated. Not until near the end of

his life in 1951 did he release the last

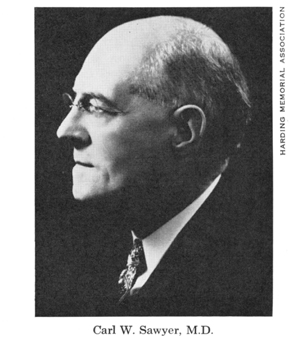

of his holdings.23 He decided to give

them personally to Dr. Carl W. Sawyer,

then President of the Memorial

Association and guardian of the Harding

Papers, while he was a patient

at the latter's Marion sanatorium.

It may have been the donation of the

senatorial papers by Christian in

addition to a growing impulse that the

time had come to open Harding's

papers for historical purposes that

prompted Dr. Sawyer to begin the

task of arranging and processing the

immense collection. In the mid-1950's

a vault was installed in the basement of

the Harding home where all of

the papers, except those from the nearly

forgotten Marion Star material,

which was in the attic, were placed in

six fireproof files.24 Then Dr. Sawyer

80 OHIO HISTORY

began the work of identifying the

sections of material, arranging them, and

having them processed by his secretary.

Since the papers from the White

House Executive Wing files were still in

their original folders and order,

and probably since the official

correspondence of the Harding Administra-

tion seemed of paramount importance, Dr.

Sawyer had his secretary begin

the processing with this section in

1957.25 Two items in the processing of

the Executive Wing material were of

special importance to those who would

use the papers later. First, the labels

and numbers of the original White

House folders were copied onto the new

Harding Memorial folders to which

the material was transferred, thereby

leaving the invaluable convenience

of Christian's filing and

cross-reference systems intact for researchers.26

Second, new folders were made even if

the old ones were empty, thus making

obvious the spaces from which material

was missing.27 Once the Executive

Wing papers were placed in new folders

and each sheet numbered, the

surviving White House private office

material, the typed copies made in

1925, the 1920-1921 campaign and

senatorial correspondence, and finally

the contents of the rediscovered Star

files were similarly processed by Dr.

Sawyer and his secretary by March,

1964.28

In the fall of 1963, then, when the

Memorial Association began to release

the Harding Papers into the possession

of The Ohio Historical Society,

the myth of total destruction was

publicly exploded.29 It became immediately

apparent that not only material from the

President's White House private

office and the Star files, which

had passed through Mrs. Harding's censor-

ship, but also huge amounts of papers

from the Executive Wing files and

from Christian's holdings, which she had

not screened, had been preserved.

It remained for eager scholars to begin

the research, however, that would

reveal the extent of the knowledge to be

gained from this previously untapped

storehouse. Although this task is still

in progress, it is possible to outline

in a general way the types of

information which the various parts of the

Harding Papers are yielding:

The story of Harding's business and

political careers in Ohio from 1888

to 1914 is recorded in the material

which fills forty-nine manuscript boxes

from the newspaper office files.30 While

the amount of the business corre-

spondence steadily increased over the

period, the political mail fluctuated

with Harding's political fortunes.31

During his 1900-1904 terms as state

senator and his 1904-1906 term as

lieutenant governor, the papers bulge.

They are especially full in 1905 when Harding

was urged to oppose

incumbent Republican Governor Myron T.

Herrick for the gubernatorial

nomination. His failure to seize this

opportunity brought him into the

eclipse suffered by the Joseph Foraker

faction of the party thereafter,

and the Harding papers reflect the

decline. For 1910, when Harding finally

sought and gained the Republican

nomination for governor, the material

is once again extensive, but it stops

abruptly in mid-October, thus omitting

his defeat at the polls. Whether or not

this is evidence of weeding done

by Mrs. Harding, the extant

correspondence from the Star files is a prime

source for interpreting Harding's

success as a businessman and his rise

to national attention as a state politician.

|

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE HARDING PAPERS 81 |

|

|

|

Although the Papers contain a massive quantity of material on Harding's election to the United States Senate in 1914, virtually no correspondence is included from his first two years in office (1916-1917).32 Thereafter, his Washington senatorial papers fill thirteen manuscript boxes.33 The senatorial correspondence which was received and sent from the Marion campaign office is much more extensive, filling 144 such boxes.34 This section of the Papers is especially valuable. It not only includes letters from prominent individuals such as James M. Cox, Nicholas Murray Butler, Charles Evans Hughes, Eugene V. Debs, Henry C. Wallace, Will Hays, and William Howard Taft, but also contains material regarding the conditions in numerous countries and the prospective government appointments of ambassadors to these countries and also data on such topics as the coal situation, the Brotherhood of Trainmen, and the selection of cabinet members, which foreshadowed some of the impending issues of the Harding Administration. Directly related to the late senatorial papers is the outstanding collection of those preserved from the presidential election and pre-inaugural period. This material provides a prime opportunity to analyze the presidential nomination and election of Harding. Ten manuscript boxes of correspondence deal with pre-convention and presidential primary matters.35 One hundred and forty-three manuscript boxes contain the very revealing official campaign correspondence, arranged alphabetically by states.36 Eighteen manuscript boxes offer the contents of the election files of the Republican National Committee, also arranged by states.37 Finally, fifteen manuscript boxes hold letters of a personal nature from Harding's months of campaigning and awaiting inauguration.38 |

82 OHIO HISTORY

In many respects the papers dealing

directly with Harding's days in

the White House are the most important.

Those from his private office

that escaped destruction by Mrs. Harding

fill sixteen manuscript boxes.39

This material is especially enlightening

on issues of foreign affairs since

it contains not only intimate, personal

letters from leading political figures

on subjects as diverse as the Genoa

Conference and the China situation,

but also because it has much of

Harding's correspondence with United States

ambassadors abroad, such as George

Harvey in Great Britain. In some

cases the typed copies of over five thousand

pieces of the private office col-

lection which were made in 1925 contain

valuable letters not as yet found

in the Harding Papers themselves.

The material from the Executive Wing

files which fills 352 manuscript

boxes provides the broadest contemporary

view of the Harding Administra-

tion.40 Since the papers in this section

have been kept in secretary Christian's

filing arrangement, research by topic is

simplified by the folder labels and

by the convenience of using the original

cross-reference system. It is facil-

itated further by an

alphabetically-arranged card index of the folder titles

prepared at Marion and by a

comprehensive inventory compiled at The

Ohio Historical Society which lists the

titles of all of the labeled folders

and gives a resume of the contents of

each box in the entire collection. Thus

it is possible to select the White House

correspondence of each executive

department from Agriculture to War.

Hundreds of topics related to the

Harding presidency and after are also

available. A few of these include the

Civil Service Commission, Government

Printing Office, Interstate Commerce

Commission, United States Railroad

Commission, Railroad Strike of 1922,

Coal Strike, Negro Race, Indian Affairs,

National Debt, Bankers Financial

Committee, United States Labor Board,

Federal Reserve Board, Federal

Trade Commission, Veterans Affairs, Debs

Case, United States Shipping

Board, War Finance Corporation, Farmers

Problems, and Applications For

Government Jobs and Appointments

arranged by states.

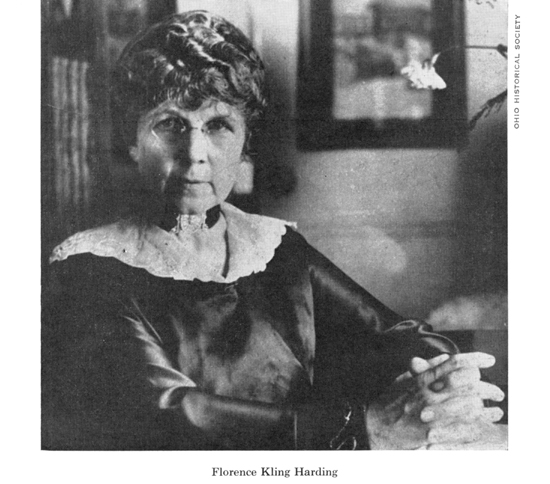

The remainder of the material in the

Harding Papers as received from

the Memorial Association is of

peripheral, but useful, quality. It contains

many holograph and typed copies of

Harding's speeches,41 his Executive

Orders and Proclamations,42 information

concerning his fateful Alaska trip,

death, and messages of sympathy to his

widow.43 The papers of persons

close to Harding are also included. Mrs.

Harding's correspondence, mostly

from the 1920-1923 period, awaits a

biographer.44 Kathleen Lawler, Harding's

stenographer in the pre-presidential

days, is represented by a few letters

and the lengthy draft of her

unsuccessful attempt to publish the story

of "The Hardings I Knew."45

A few personal Harding letters to George B.

Christian, Sr.,46 some correspondence of

Drs. Charles E. and Carl W.

Sawyer in regard to Harding Memorial

Association affairs,47 and the 1928-

1933 private papers of George B.

Christian, Jr.,48 complete the collection

of Harding Papers once held by the

Memorial Association and now open

to the public at The Ohio Historical

Society.

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE HARDING

PAPERS 83

In 1961, as soon as the Society had

solid hopes of becoming the ultimate

beneficiary of the Papers, it began a

concerted effort to build adjunct col-

lections of the correspondence of

Harding's contemporaries and intimates.

As a result, fourteen collections have

been acquired which add significantly

to the breadth of view that can be

gained of Harding and his age.49 The

papers of Charles E. Hard, Portsmouth

editor and political figure;50 Newton

Fairbanks, chairman of the Ohio

Republican State Central Committee from

1916 to 1920;51 and Alfred

"Hoke" Donithen, Marion lawyer and close

associate of Harding,52 who

were all early supporters of the owner of the

Marion Star for the 1920

Republican nomination, help to document the

circumstances and events that brought

political distinction to Harding. The

one hundred and fifty letters that have

been preserved from the estate of

Walter F. Brown, Toledo lawyer and

railroad executive who had at first

backed General Leonard Wood but switched

to Harding at a crucial point

in the 1920 campaign, also help to

illuminate this phase of Harding's life.

The contemporary political currents are

reflected further in the extensive

papers of Arthur L. Garford, Elyria

industrialist and often political candidate

in Ohio;53 Simeon Fess,

Antioch College president and United States

senator from 1923 to 1935;54

and Frank B. Willis, Ohio governor from 1915

to 1917, nominator of Harding at the

1920 Republican Convention and

holder of Harding's former senatorial

seat from 1921 to 1928.55 The Ohio

political climate during Harding's

presidency is recorded in the friendly,

personal letters of Mary E. Lee, a party

worker and presidential appointee

as postmistress at Westerville, Ohio.56

The most personally revealing letters

of Harding appear in the recently

acquired Frank E. Scobey collection.57

Scobey and Harding became well

acquainted during their days in the Ohio

legislature, and although Scobey moved

to Texas later, he urged his friend

to seek the 1920 nomination and worked

to deliver the Texas delegation

into his hands. As a reward Scobey was

made director of the mint in 1922.

Harding seems to have felt completely

free to put his inmost feelings into

his letters to the Scobeys. The

correspondence of the close friend of the

Hardings and one-time managing editor of

the Harding Publishing Com-

pany, Malcolm Jennings, also contains

personal touches.58 A few additional

such pieces have been secured in

relation to Harry M. Daugherty, Harding's

senatorial and presidential campaign

manager and Attorney General. Finally,

two private collections of Harding

material drawn from many sources that

had been gathered by Cyril Clemens,

descendant of Mark Twain, who had

intended to write a biography,59 and Ray

Baker Harris, librarian for the

Scottish Rite in Washington, who had

similar plans,60 are now valued

adjuncts to the Harding Papers.

If Warren G. Harding is to have a second

chance to clarify his position

and that of his age in the minds of

Americans, his own papers, so long

suppressed, must secure it for him. The

articles that appear in this edition

of Ohio History are indicative of

the scope and depth of the yield that might

be expected from this 350,000 sheet

reservoir of information. If the opening

84 OHIO HISTORY

of this source results in the production

of a more sophisticated and objective

interpretation of the life and times of

the twenty-ninth president, April

25, 1964 will have been a landmark in

American historiography.

THE AUTHOR: Donald E. Pitzer is

Assistant Professor of History at

Indiana

State University, Evansville Campus.