Ohio History Journal

TED C. HINCKLEY

The Politics of Sinophobia: Garfield,

the Morey Letter, and the Presidential

Election of 1880

Looking backward from the 1890s and

ruminating on the almost

dozen presidential contests with which

he had been familiar, Charles

Francis Adams, Jr., reflected, "So

far as the country as a whole is

concerned, the grand result would in

the long run have been about

the same whether at any particular

election"-with the exception of

1864-"the party I sympathized with

had won the day or whether

the other party had won it."

Brother Henry was even more cynical

of Gilded Age government. "The

political dilemma was as clear in

1870 as it was likely to be in 1970 ....

Nine-tenths of men's

political energies must henceforth be

wasted on expedients to piece

out-to patch-or, in vulgar language, to

tinker-the political

machine as often as it broke

down."1

While the Adamses compared their age's

politicos with the sages

of George Washington's era, our

generation is inclined to recall a

less Olympian leadership. And when we

soberly consider how our

future increasingly rests on decisions

made in Teheran and Riyadh,

invidious phrases like "piece

out," "patch," and "tinker" may not

seem so unreasonable.

Philosopher-presidents charted inspirational

voyages for early America's

"chosen people"; henceforth simply

keeping the Republic's ship of state

afloat could be triumph enough.

Possibly this explains why historians

now seem less inclined to

ridicule as "ineffectual"

America's 1865 to 1901 presidents.2 A cen-

Professor Ted C. Hinckley teaches

history at San Jose State University and is

now on the State Historic Resources

Commission of the California Department of

Parks and Recreation.

1. Edward Chase Kirkland, Charles

Francis Adams, Jr. 1835-1915: The Patrician at

Bay (Cambridge, Mass., 1965), 169; Henry Adams, The

Education of Henry Adams: An

Autobiography (Boston, 1961), 280-81.

2. As Robert Kelley notes, "The

politics of the Gilded Age, like that of every other

period, have their own inner validity

and reality." The Shaping of the American Past

(Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1978), 442. H.

Wayne Morgan admonishes scholars to take the

382 OHIO HISTORY

tury ago, as today, distinctions between

the two major parties were

frequently blurred. For all the

widespread alarm awakened by riot-

gutted Pittsburghs and Haymarket Square

blood-lettings,

Democrats and Republicans alike eschewed

ideological panaceas.

The root problems of America's booming

industrialization were on-

ly vaguely perceived by the electorate;

simple solutions were rarely,

if ever, possible. Not until near the

century's turn would a genuinely

national political perspective really

challenge the Jacksonian con-

fidence in self-help, small

institutions, and regionalism.3

Because third parties did signal a

number of the Gilded Age's

socioeconomic discontents while the two

major parties wobbled

across each other in the middle of the

road, there is the assumption

that the Republican and Democratic

election contests really served

little purpose, or as the Adams brothers

would have insisted, there

was a wasteful dissipation of political

energies.

This essay suggests that those

quadrennial presidential cam-

paigns were in and of themselves an

efficient means of venting

public tensions and articulating public

issues, two elements which

are indispensable for maintaining a

democratic society. And fur-

thermore, notwithstanding all the

torchlight hoopla, these

rhetorical battles did influence

subsequent legislation. Certainly the

magnification of America's anti-Chinese

labor feelings during the

1880s presidential struggle demonstrated

this. It served as a

catharsis for America's sinophobia, and

accelerated Congressional

passage of the historic, if misguided,

1882 Chinese exclusion.4

Historian Leonard Dinnerstein believes

the 1880s contest was

"one of the most insignificant in

United States History"; for New

Yorker Thomas Collier Platt, it was

"a sullen campaign."5 The

Democratic and Republican differences

more seriously. Indeed, the Preface and

Bibliography to his distinguished From

Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics,

1877-1896 (Syracuse, N.Y., 1969) is required reading for the

historian of these years.

Examples of the traditional

interpretation are Samuel Eliot Morison, et al, A Concise

History of the American Republic (New York, 1977), II, Chap. 23, "The Politics of

Dead

Center 1877-1890"; and Vincent P. DeSantis, The

Shaping of Modern America:

1877-1916 (Boston, 1973), Chap. 3, also, "The Politics of

Dead Center." Suggestive of

where fresh thinking can lead is Geoffrey Blodgett,

"A New Look at the American

Gilded Age," Historical

Reflections, I (Winter 1974) 231-44.

3. For a recent and impressive analysis

of this thesis, see Morton Keller, Affairs of

State: Public Life in Late Nineteenth

Century America (Cambridge, Mass.,

1977).

Two other germane studies are Howard Mumford Jones, The

Age of Energy ... (New

York, 1971) and Robert H. Wiebe, The

Search for Order (New York, 1967).

4. Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, A

History of the United States Since the Civil War

(New York, 1931), IV, 297 ff; John A.

Garraty, The New Commonwealth, 1877-1890

(New York, 1968), 208.

5. Leonard Dinnerstein, "Election

of 1880," in Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., History

of American Presidential Elections,

1789-1963 (New York, 1971), II, 149;

hereafter

cited as HAPE; Thomas C. Pratt, Autobiography

(New York, 1910), 134.

Politics of Sinophobia 383

Southern question has gone into eclipse,

and the nation was enjoy-

ing relative prosperity. As the

platforms of the two major parties

tended to merge, politicians frequently

resorted to hyperbole and

personal vituperation. Not until the

next decade's depression and

the farmers' revolt would fresh policies

match dramatic politicos.

While the wafer-thin presidential

victories of the 1880, 1884, and

1888 campaigns reflected "an era of

the closest balance of party

strength in American history," it

is a mistake to extrapolate from

this tacit public consensus that the

age's respective Republican and

Democratic platforms lacked substance.6

They might equivocate, or

remain silent, on what we now regard as

the critical issues of the

day, but their campaign documents did

not merely repeat "tradi-

tional platitudes." Presidential

aspirants and their lieutenants cor-

rectly discerned the implicit warnings

in their narrow mandates: to

struggle against the popular tide could

prove fatal. In truth,

America's cruel Civil War, followed by

the rancorous Bloody Shirt

campaigns of the seventies, left many

Americans feeling that they

had "had a surfeit of political

conflict."7

In his classic The American

Commonwealth, published during the

1880s, James Bryce reported the decade

as "comparatively quiet."

Bryce estimated that nineteen out of

twenty citizens "had no

special interest in politics."8 But

if, as Bryce reported, America's

electorate was unwilling to come to

grips with new, enormously

complex economic questions, certain

segments of the body politic

eagerly unfettered their frustrations

with "strikes, riots, vigilan-

tism, and lynching."9 Big

business and the railroads were prime

6. Svend Petersen, A Statistical

History of the American Presidential Elections

(New York, 1963), 48-56 ff; Alfred E.

Binkley, American Political Parties: Their

Natural History (New York, 1962), 309.

7. HAPE, 1504. David J. Rothman, Politics

and Power: The United States Senate

1869-1901 (New York, 1969), 263; DeSantis, The Shaping, 37.

Richard Hofstadter, "The

Development of Politicial Parties"

in John A. Garraty, Interpreting American History

... (London, 1957), I, 157.

8. James Bryce, The American

Commonwealth (New York, 1959), edited by Louis

M. Hacker, I, 273, 285. Just how far

this spirit of accomodation had gone was the

U.S. Supreme Court's 1883 declaration

that the adjustment of social relations of in-

dividuals was beyond the power of

Congress, and the Court's destruction of the

1875 Civil Rights Act. James M.

McPherson, The Abolitionist Legacy

...

(Princeton, 1975), 22.

9. Keller, Affairs, 486.

10. Roger Daniels, "Westerners from

the East: Oriental Immigrants Reappraised,"

Pacific Historical Review, XXXV (November, 1966), 373-83 ; and his "American

Historians and East Asian

Immigrants," Pacific Historical Review, XLIII

(November, 1974) 449-72. Equally

indispensable is John Higham, Strangers in the

Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925 (New York, 1969). Illustrating the

range of reinterpretation are David J.

Langum, "Californios and the Image of In-

dolence," Western Historical

Quarterly, IX (April, 1978), 181-96; and Luther W.

384 OHIO HISTORY

targets for the wrath of those whose

autonomy was being eroded by

mass mechanization and the corporate

society. A more immediate

scapegoat, particularly for Westerners,

was the Asian stereotype,

"John Chinaman."

Historian Roger Daniels has reminded us

that there never oc-

curred the flood of Chinese immigrants

pictured in racist

mythology. The Chinese were but one

among many minority groups

who were victimized by American

xenophobia. Today social scien-

tists have amassed a considerable body

of scholarship on the

diverse ramifications of nativism.10

Individuals who persist in see-

ing the matter simply as white man vs.

Black, white man vs. Asian,

et cetera, play the fool; xenophobia was

and is virtually universal.

Certainly nineteenth century America's

sinophobia, like its

negrophobia, was a grim and important

historic reality.11

Chinese had visited the United States

since the beginning of the

century; however, it was shock waves

from Mother Lode diggings

that really alerted them to American

opportunities. Fewer than 400

immigrants in 1849, by 1852 their number

had grown to 25,000. The

passage in 1868 of the Burlingame

Treaty, which permitted the

Chinese unrestricted immigration into

the United States, helped

sustain this trans-Pacific movement.

Desperate conditions within

China propelled tens of thousands of

them to emigrate to scattered

points all about the Pacific Basin and

beyond. Thousands who were

at first welcomed in Peru and Cuba found

themselves "so badly

treated as to give rise to international

scandals" between Lima and

Peking, while in Spanish Cuba some

actually joined the island's

revolutionary movement.12 America's

welcome also turned sour. It

is easy enough to understand why

Massachusetts employers' use of

Spoehr, "Sambo and the Heathen

Chinee: California's Racial Stereotypes in the

Late 1870s," Pacific Historical

Review, XLII (May, 1923), 185-204.

11. Among the numerous studies featuring

America's anti-Chinese activities are

Stuart Creighton Miller, The

Unwelcome Immigrant: The American Image of the

Chinese, 1785-1882 (Berkeley, 1969); and Elmer C. Sandmeyer, The

Anti-Chinese

Movement in California (Urbana, Ill., 1939). The impact of status anxieties

has been

probed by Alexander Saxton, The

Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-

Chinese Movement in California (Berkeley, 1971). To gain a multi-ethnic com-

parative view, see Robert F. Heizer and

Alan J. Almquist, The Other Californians:

Prejudice and Discrimination Under

Spain, Mexico and the United States to 1920

(Berkeley, 1970).

12. Kenneth Scott Latourette, A Short

History of the Far East (New York, 1957),

378 ff; Gunther Barth, Bitter

Strength (Cambridge, Mass., 1964). H. Brett Melendy,

The Oriental Americans (New York, 1972) provides a splendid review of all the

major

East Asian immigrant groups. Also see,

Rose Hum Lee, The Chinese in the United

States of America (Hong Kong, 1960), 9; Magnus Morner, Race Mixture in

the

History of Latin America (Boston, 1967), 131.

Politics of Sinophobia 385

Chinese as strike breakers angered white

workers, but it is difficult

to comprehend western Americans' fierce

antipathy, at times an

almost pathological fear of what a

swelling number discerned as

"degenerate Chinese." Daniels

believes that as early as 1870, "when

Chinese formed about 10 percent of the

state's population, the anti-

Chinese issue had become perhaps the

most important" in Califor-

nia.13

Certainly America's protracted

depression of the 1870s helped

fuel California's combustible

sinophobia. An 1876 Congressional

Joint Committee's western tour angered

Western exclusionists.

Ironically the Committee's anti-Chinese

report, authored by Califor-

nia's Senator Aaron A. Sargent, aroused

nativists elsewhere in the

United States. A Southern congressman

actually advocated that

"the subjects of China"

presently within America be colonized on

"a tract of land in one of the

Territories of the United States, as

remote as possible from white

settlements." As the seventies ended,

the quantity of sinophobia printed in

the nation's newspapers, and

spreading across the country in pamphlet

form, had reached serious

proportions.14 Within the

Golden State it had become

unques-

tionably the premier political issue.

It was probably in California's mining

camps during the fifties

that sinophobia and the "enduring

theme of [Chinese] cultural in-

feriority was launched." After the

Civil War, California's prejudice

against non-whites proved so strong that

the state refused to ratify

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments,

fearing the Chinese

would thus acquire equal civil rights.15

In 1868, California's

Democratic gubernatorial candidate

attacked any extension of the

suffrage to "inferior races"

such as Negroes and Chinese. The

13. Lucile Eaves, A History of

California Labor Legislation ... (Berkeley, 1910).

II, 138. Although dated in her analysis

of anti-Orientalism, Mary Roberts

Coalidge's Chinese Immigration (New

York, 1909) also includes much valuable

material on this topic. Also see, Roger

Daniels, The Politics of Prejudice ... (New

York, 1968), 16.

14. S.C. Miller, The Unwelcome, 186

ff; M.B. Starr, The Coming Struggle; Or

What the People on the Pacific Coast

Think of the Coolie Invasion (San

Francisco,

1873); Raphael Pumpelly; "Our

Impending Chinese Problem," Galaxy, (January,

1869), 22-23; Sandmeyer, The

Anti-Chinese, 81-82; Aaron A. Sargent, Immigration

of Chinese [Senate Speech, May 2,

1876] (Wash., D.C., 1876). Also see,

Starr, The

Coming Struggle; Henry J. West, comp., The Chinese Invasion (San

Francisco,

1873); Robert McClellan, The Heathen

Chinee: A Study of American Attitudes

Toward China, 1890-1905 (Columbus, Ohio, 1971), carries the controversy all the

way

up to 1904 when Chinese exclusion had

become virtually permanent.

15. Rodman, W. Paul, "The Origins

of the Chinese Issue in California," Mississip-

pi Valley Historical Review, XXV (September, 1938), 181-96; Leonard Pitt, "The

Beginnings of Nativism in

California," Pacific Historical Review, XXX (September,

1961), 23-38; Melendy, The Oriental, 30-39;

Sandmeyer The Anti-Chinese, 46-47.

386 OHIO HISTORY

Republican leadership, on the other

hand, apparently

underestimated the swelling current of

sinophobia, for it endorsed

the recently concluded Burlingame

Treaty. Mob violence

throughout the seventies provided ample

evidence of the growing

anti-Chinese sentiment. In 1871, a

roaring Los Angeles crowd

dispatched eighteen or nineteen

"Celestials heavenward."16

Murderous outbreaks against Chinese at

Antioch, Truckee, Gilroy,

and San Diego seared the mid-seventies.

As the sounds of gunfire

and burning buildings mingled with the

incendiary polemics of

Pacific Slope sinophobes, leading

Chinese-Americans countered by

memorializing the President of the

United States to weigh "the

other side of the Chinese

question." The ineffectualness of their

pleas was manifest when both the

Democratic and Republican plat-

forms of 1876 included anti-Chinese

immigration planks. Both of

these documents declared against Chinese

and/or imported labor un-

til the century's end.17 Far

West sinophobes doubtless applauded

California's Democratic Governor William

Irwin's racist rallying

cry: "An irrepressible conflict

between the Chinese and ourselves-

between their civilization and

ours-" had begun. By 1879, this

groundswell of nativism combined with

sufficient other national

pressures to place a Chinese exclusion

bill on President Rutherford

B. Hayes' desk. Hayes vetoed it.18

For Californians, 1879 had been a year

of decision. The menace of

San Francisco's Chinese-hating demagogue

Denis Kearney and his

Workingmen's Party had peaked.

Nevertheless, California's new

state constitution-written during that

feverish year-denied the

suffrage to all Chinese and prohibited

them from employment on

16. Melendy, The Oriental, 32;

Keller, Affairs of State, 57; Walton Bean, Califor-

nia: An Interpretative History (New York, 1968), 235-36. Richard H. Dillon dates

August 4, 1863, as San Francisco's first

anti-Chinese riot. The Hatchet Men ...

(New York, 1962), 62.

17. Salinas City Index, March 22,

1877; John Walton Caughey, California

(Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1953), 385-87;

Melendy, The Oriental, 37-38; Representative

Chinamen in America, Facts Upon the

Other Side of the Chinese Question: With a

Memorial to the President of the

United States (San Francisco, 1876).

See also,

Memorial of Six Chinese Companies to

the Senate and the House of Representatives

of the United States (San Francisco, 1877). Nor were the Chinese without old

friends

among the Anglos. See, for example,

William Speer, A Humble Plea... (San Fran-

cisco, 1856); Lee, The Chinese, 12;

Kirk B. Porter and Donald B. Johnson, National

Party Platforms: 1840-1964 (Urbana, Ill., 1966), 49-118.

18. Daniels, The Politics of

Prejudice, 16-17; Keller, Affairs of State, 157. Thomas

A. Bailey briefly examines the why of

Hayes' veto in his A Diplomatic History of the

American People (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1974), 393-95; for fresh

digging, see, Gary

Pennanen, "Public Opinion and the

Chinese Question 1876-1879," Ohio History, 77

(Winter, 1968), 144 ff.

|

Politics of Sinophobia 387 |

|

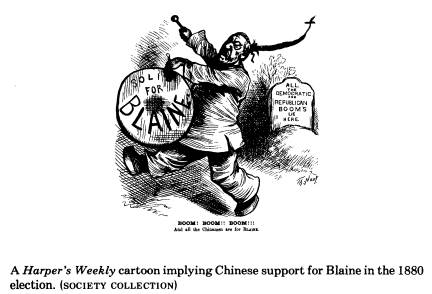

public works. Further discriminatory measures would follow; predictably, these excesses would result in numerous court challenges.19 For the moment, however, attention would be focused on the Chinese issue and America's 1880 presidential battle. In the 1880 campaign the platforms of both major parties, as well

19. Ping Chiu, Chinese Labor in California, 1850-1880: An Economic Study (Madison, Wisc., 1967), 138; Ralph J. Roske, Everyman's Eden: A History of Califor- nia (New York, 1968), 385-88. The standard work on the 1879 constitution is Carl B. |

388 OHIO HISTORY

as that of a third party, the

Greenbacks, included a stand on

Chinese labor. The Democrats wanted the

Burlingame Treaty of

1868 amended to prevent further Chinese

immigration, "except for

travel, education, and foreign

commerce,..." The Republicans

declared "the unrestricted

immigration of the Chinese as a matter

of grave concernment," and that

action by China and the United

States "would limit and restrict

that immigration by the enactment

of such just, humane and reasonable laws

and treaties ..." The

Republicans' more moderate tone was

necessitated in part by the

fact that President Rutherford B. Hayes'

representatives were then

negotiating in Asia to slow the

trans-Pacific traffic into California.20

Furthermore, the public would condemn

any reprisals on American

Christian missions and traders in China

as a Republican failure. The

Greenback Party platform put the matter

bluntly: "Slavery being

simply cheap labor, and cheap labor

being simply slavery, the im-

portation and presence of Chinese serfs

necessarily tends to

brutalize and degrade American labor,

therefore immediate steps

should be taken to abrogate the

Burlingame Treaty."21

The Democrats, determined to win back

the White House, picked

a candidate whose Civil War credentials

immunized him from

"Bloody Shirt" reproach:

General Winfield S. Hancock who had

fought for the Union at Gettysburg. Nor

was the handsome Han-

cock merely an honored Union man. During

Reconstruction he had

practiced a relatively even-handed

administration throughout

Texas and Louisiana. Indeed, by 1880 the

affable Hancock was not

readily identified with any

controversial issue. In his acceptance let-

ter, Hancock's running mate, William H.

English, promised that

"The toiling millions of our people

will be protected from the

Swisher, Motivation and Political

Technique in the California Constitutional Con-

vention, 1878-79 (Claremont, Calif., 1930); equally vital for nineteenth

century

California politics is Winfield J.

Davis, History of Political Conventions in Califor-

nia, 1849-1892 (Sacramento, 1893). To follow up the judicial

decisions, see L.S.

Sawyer, Reports of Cases Decided ...

(San Francisco, 1873-1891). Carl Brent

Swisher has provided us an absorbing

account of how California's most famous

jurist for these years zig-zagged on the

Chinese Question in his Stephen J. Field,

Craftsman of the Law (Chicago, 1969), Chap. 8.

20. HAPE, 1518-27. The 1868

treaty had permitted Chinese the right of free im-

migration into the United States. By the

time of the fall 1880 presidential campaign,

however, a U.S. diplomatic commission to

China had succeeded in obtaining a new

treaty that enabled the United States to

"regulate, limit, or suspend," but not ab-

solutely prohibit the entry of Chinese

laborers. Julius W. Pratt, A History of United

States Foreign Policy (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1955), 360; Tyler Dennett, Americans

in East Asia (New York, 1963), 541-43.

21. David L. Anderson, "The

Diplomacy of Discrimination: Chinese Exclusion,

1876-1882," California History, LVII

(Spring, 1978), 32-45; HAPE, 1522.

Politics of Sinophobia 389

destructive competition of the Chinese,

and to that end their im-

migration will be properly

restricted."22

Because President Hayes had earlier

rejected a second term, the

Republican presidential convention

remained relatively open. This

was demonstrated when a one-time college

president-become-

politician gave the nominating address

for party war-horse John

Sherman, and on the thirty-sixth ballot

ended up himself becoming

the nominee. Ohio Congressman James

Abram Garfield, like Han-

cock, was a combat veteran. A persuasive

orator and tested House

Republican leader, Garfield was well

informed on national matters.23

To placate New York Stalwarts

(essentially the followers of Senator

Roscoe Conkling), resentful because

ex-President Grant had been

denied a third run for the presidency,

the party chose as Garfield's

running mate Chester Alan Arthur, a

recent Collector of the Port of

New York whom President Hayes had

earlier removed from office

because of his refusal to discontinue

his excessive politicking for

Conkling. New York, along with

Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana,

was a state Republicans had to carry to

defeat the Democrats now

armed with their Solid South phalanx.

Throughout the 1880 cam-

paign, New Yorker Arthur repeatedly

confirmed how adept were his

fund raising skills.24

Having moved to shore up Eastern allies,

Garfield next turned to

the West. In his acceptance letter of

July 12, 1880, he had spoken

optimistically about the pending treaty

which would reduce Chinese

immigration, while promising "a

great increase of reciprocal trade

and the enlargement of our

markets." Garfield had been among

those who had urged President Hayes to

veto a bill in 1879

22. Allen Johnson and Dumas Malone,

eds., Dictionary of American Biography

(New York, 1960), IV, 221-22; HAPE. 1501

and 1546. A brave first effort to compare

presidents and prejudice is George

Sinkler, The Racial Attitudes of American

Presidents from Abraham Lincoln to

Theodore Roosevelt (New York, 1972).

23. Garfield biographies used in this

study have been primarily Margaret Leech

and Harry J. Brown, The Garfield

Orbit: The Life of President James A. Garfield

(New York, 1978); Allan Peskin, Garfield

(Kent, Ohio, 1978); Theodore Clarke Smith,

The Life and Letters of James Abram

Garfield, 2 vols. (New Haven, 1915);

and John

M. Taylor, Garfield of Ohio: The

Available Man (New York, 1970). Also see, Richard

C. Bain, Convention Decisions and

Voting Records (Wash., D.C., 1960), 114-15;

Porter and Johnson, National Party

Platforms, 60-62; Chauncey DePew, Memories

of Eighty Years (New York, 1922), 108.

24. George H. Mayer, The Republican

Party 1854-1966 (London, 1967), 200-02,

provides a fine perspective of the

larger national political picture for these years. A

good narrative history of the 1880

contest is Herbert J. Clancy, The Presidential

Election of 1880 (Chicago, 1958). Also see Alexander Flick, ed., A History of the

State of New York, 9 vols (New York, 1933-37), I, 166; Rothman, Politics

and Power,

32; Thomas C. Reeves, "Chester A.

Arthur and the Campaign of 1880," Political

Science Quarterly, LXXXIV (December, 1969), 628-37.

390 OHIO HISTORY

abrogating the Burlingame Treaty. Angry

attacks then directed at

Garfield by sinophobes had hurt. Now in

the summer of 1880, and

increasingly aware that every electoral

vote was critical, Garfield

summarized his opinion of the Asian

arrivals: "The recent move-

ment of the Chinese to our Pacific

Coast... is too much like an im-

portation to be welcomed without

restriction; too much like an inva-

sion to be looked upon without

solicitude." A Republican campaign

book justified President Hayes' veto by

first printing his message,

then by warning what a sudden treaty

abrogation might mean to

"our citizens in China, merchants

or missionaries."25

Understandably, California Democrats

maneuvered to compound

Garfield's "shameful support"

of President Hayes' "infamous

veto." One Democratic pamphlet

cleverly pasted together the

various opinions of prominent

Republicans, aiming to hoist them on

their own Chinese petard. For example,

the pamphlet credited

Senator Oliver P. Morton as saying,

"The intellectual stagnation in

China is the result of their

institutions." And further on it cited him

as declaring, "the invitation we

extended to the world, cannot and

ought not to be limited or controlled

by race, or color, nor by the

character of the civilization of the

countries from which immigrants

may come." Candidate Garfield was damned for "his contempt

for

the working man of his own race, and his

willingness to force white

American free laborers into competition

for their daily bread with a

race that knows no God, no Morality and

no obligations of social

decency."26

In 1880, three bellwether states

performed the role of what the

New Hampshire primary would a century

later. Maine, Ohio, and

Indiana held their gubernatorial

contests well in advance of the

November elections. In none of these

pre-presidential contests does

the Chinese question appear to have

loomed large. The victory of a

Democratic governor in Maine on

September 13 alarmed

Republican organizers, but they recouped

with wins in Ohio and In-

diana.27 With the national

election less than two months off, both

parties targeted on the opposition

candidate. Cartoonist Thomas

Nast sketched Hancock as a dignified old

soldier-benignly ig-

norant of the paramount national

problems. Democrats branded

25. New York Times, June 9 and

16, 1880; HAPE, 1537; Smith, Life and Letters,

II, 677; Edward McPherson, A Handbook

of Politics for 1880 (San Francisco, 1880),

39-44. A consideration of what candidate

Garfield actually may have believed about

racial matters is in Sinkler, Racial

Attitudes, 243.

26. N.a., General Garfield and

Chinese Immigration (n.p., 1880), a four-page hand-

out, Research Library, University of

California, Los Angeles, California.

27. Taylor, Garfield of Ohio, 214.

Politics of Sinophobia 391

Garfield for his earlier involvement

with Credit Mobilier, his "liber-

tine licentiousness," his

"thefts during the war," and for just about

any act of fiction Democratic editors

could contrive.28

Examination of the Garfield

correspondence leaves little doubt he

was in command of his party and was

determined to minimize

mistakes. Warned by Western Republicans

that his previous stand

on Chinese immigration had injured him,

Garfield tiptoed about

this combustible, the pending

renegotiated immigration treaty of-

fering him a degree of insulation. And

then on October 20, with the

election but a few weeks off, the Morey

Letter and Garfield's alleged

sinophilia became front page news.29

The letter first appeared in New York

City's Truth, an organ hard-

ly distinguished for truthful

publication. Garfield's purported letter

to H.L. Morey of Lynn, Massachusetts,

dated January 23, 1880,

read:

Dear Sir:

Yours in relation to the Chinese problem

came duly to hand. I take it that

the question of employes [sic] is only a

question of private and corporate

economy, and individuals or companies

have the right to buy labor when

they can get it cheapest.

We have a treaty with the Chinese

Government which should be

religiously kept until its provisions

are abrogated by the action of the

general Government, and I am not

prepared to say that it should be

abrogated until our great manufacturing

and corporate interests are con-

served in the matter of labor.30

The last sentence was lethal. That it

could anathematize Garfield

to large numbers of westerners was

indisputable. But was the letter

itself above dispute, and had the

Republican candidate actually

penned the document? On October 23, and

just below its subtitle

"THE WHOLE TRUTH, AND NOTHING BUT

THE TRUTH,"

Truth printed a facsimile of the letter, as well as a copy of

the

envelope in which it supposedly had been

delivered. The two top

men in the Democratic Party, the

distinguished New York in-

28. Peskin, Garfield, 493 ff,

sketches a hard-hitting Garfield, a bloody-shirt waver

not above name calling-a profile not

always drawn by his other biographers.

Leech, The Garfield Orbit, 217-18;

Morgan, From Hayes, 115-18; Clancy, Presiden-

tial Election, Chap. VII.

29. Ibid., 233-34. On the letter's

political and legal ramifications before and after

the 1880 campaign as written by an

involved contemporary, see, John I. Davenport,

History of the Forged Morey Letter (New York, 1884).

30. HAPE, 1513; Clancy, Presidential

Election, 233; Rutherford B. Hayes Scrap-

book, Vol. 81, 46 ff., Rutherford B.

Hayes Memorial Library, Fremont, Ohio.

392 OHIO HISTORY

dustrialist Abram S. Hewitt and the

Democratic National Cam-

paign Manager William H. Barnum,

endorsed the letter as

genuine.31

Some days earlier, the New York Times

had magnified General

Hancock's statement that he was against

"nigger domination,"

while lauding ex-President Grant's

reminder to a New Jersey au-

dience that the Civil War was a

"Democratic War." However, the

Bloody Shirt's power to arouse the

electorate was fading. Among

Pacific Slope voters, its impact was

trifling compared with that of

the Morey Letter.

Acutely conscious of California's

sinophobia, Republican State

Senator C.C. Conger had already coupled

the Democrats with a solid

South whose leaders advocated the

importation of coolies to sup-

plant their freed Negroes. "Any man

who looks to Hancock," fumed

the San Francisco Chronicle, "or

the Democratic Party to put a

check on Chinese coolies in America is a

fool ... the South is ...

always for the cheapest and most servile

labor it can find .... Gar-

field had spoken unmistakably against

the importation of Coolie

labor to compete with our free

labor." Now the Democrats' publica-

tion of the Morey Letter aimed to

shatter their opponent's implica-

tions, just as surely as had Hancock's

artillery blasted his foes at

Gettysburg.32

The detonation of the explosive epistle

on October 20, with its re-

sounding national repercussions, stunned

the Republican leaders.

Midwestern workers were soon being

greeted at their factory gates

with copies of the Morey Letter;

"one hundred thousand copies"

were speedily railroaded to California;

and "fly-gobbler" Barnum (a

Republican expletive describing Barnum's

hasty swallowing of the

Morey Letter) had the letter translated

into various languages for

the widest possible distribution. In a

confidential letter to Garfield,

Marshall Jewell, the Republican National

Chairman, groaned that

printed handouts of the Morey Letter

were "being used by the

millions." Predictably, Democratic

newspapers made the most of

the sensation. Concurrently, Republicans

rallied to their standard

bearer. One Texan urged Garfield to

retaliate by using the "fact

that Louisiana Democratic planters have

contracted with New

Orleans firms and steamships to import

Chinese coolies from

Cuba." An Oakland, California,

citizen warned, "Great capital is be-

31. M.B. Schnapper, Grand Old Party

... (Wash., D.C., 1955), 176, contains a

photocopy of the Truth, October

23, 1880 issue.

32. New York Times, October 10,

14, 22, 28, 30, 1880; San Francisco Chronicle,

September 28, 1880.

|

Politics of Sinophobia 393 |

|

|

|

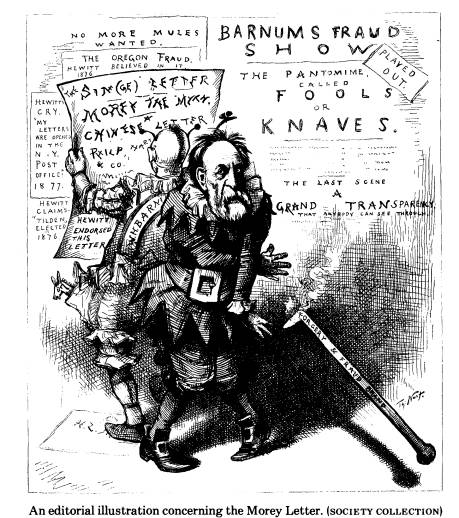

ing made out of your alleged 'Chinese letter.' A denial over your signature will have great effect on this coast." East Coast publisher Whitlaw Reid joined the Republican chorus pleading for "contradic- tion of your alleged letter on Chinese cheap labor." However, Reid cautioned Garfield, "Better be sure. . . your memory is exact and that they have no trap for you. They boast loudly of proofs."33 Having penned dozens of brief dispatches under the pressure of the campaign battle, Garfield therefore hesitated to condemn the letter as a forgery. Doubts about the document's authenticity vanished, however, when Republican detectives discovered that there was no H.L. Morey, and that the letter itself exhibited inter- nal discrepancies. In late October, charges of criminal libel were quickly brought in New York against the Truth journalist who had published the letter, Kenward Philip. Philip denied any complicity in the matter; however, his notorious reputation as a political prankster raised immediate doubts about his denial.34

33. New York Times, October 29, 1880; Clancy, Presidential Election, 234 ff; New York Times, October 27, 28, 1880; Presidential Papers of James A. Garfield, Microfilm reel no. 57, Marshall Jewell to James A. Garfield, October 22, 1880; Ridge Paschal to James A. Garfield, October 27, 1880; E.C. MacFarlan to James A. Gar- field, October 22, 1880; Whitlaw Reid to James A. Garfield, October 24, 1880. Hereafter this reel cited as PG 57. 34. New York Times, October 23, 24, 26, 1880; PG 57, M.C.D. [?] to [James A. Garfield], October 21, 1880; ibid., [?] Keffer to D.G. Servain, October 22, 1880; |

394 OHIO HISTORY

Republican leaders, aided by

newspapers, bent every effort to

publicize these late October New York

City court proceedings seek-

ing to discover who in fact had

perpetrated the fraud. The New York

Herald headlined: "The Chinese Labor Roorback [political

slander]

Destroyed," "The Alleged

Morey Letter Pronounced a Forgery,"

"Nailing a Fraud," and

"Extraordinary Efforts of the Democrats to

Circulate the Bogus Document." On

the twenty-sixth, that organ

published on its front page a facsimile

of a letter written three days

earlier by Garfield to Marshall Jewell:

Garfield "denounced the

Morey Letter as a base forgery. Its

stupid and brutal sentiment I

never expressed nor entertained."35

Shortly afterward, the Ohioan

wrote an old college chum, "It is

very gratifying to know that my

classmates are everywhere aiding in

stamping out the miserable

Morey Forgery. In the long run I think

that business will hurt the

Democrats far more than they thought it

would hurt us." Indeed,

Charles A. Dana, who had bitterly

criticized the Republican can-

didate, commented in his New York

Sun, "If a party requires such

infamous aids, that party, by whatever

name it may be called,

deserves to perish."36

But while Garfield and the Republicans

had satisfied themselves

that the letter was a fabrication, and

the daily proceedings of a New

York courtroom confirmed that the letter

was indeed a forgery, the

Democratic high command would not

jettison their damaging roor-

back. Hewitt cited it in his speeches,

and on November 1, one day

before the national election, Barnum

declared, "The genuineness of

the letter is now so fully established

that it should be clearly im-

Smith, Life and Letters, II, 1040; Hayes

Scrapbook, Vol. 81, 1; Los Angeles Herald,

October 27, and November 18, 1880; New

York Times, May 20, 1881; Philip

obituary, New York Times, February

22, 1886.

35. New York Herald, October 26,

29, 30, 1880; James A. Garfield to Marshall

Jewell, October 23, 1880, James A.

Garfield Papers, Collection 27, Ohio Historical

Society, Columbus, Ohio. A similar

dispatch to Jewell, October 22, 1880, appeared

(although not in facsimile) in the New

York Times, October 24, 1880, in which Gar-

field condemned the Morey Letter as

"a bold forgery both in its language and senti-

ment." The archaic word

"roorback" (or roorbach) for last-minute political slander is

derived from the slurs originally cast

by Baron Roorbach's Tour through the

Western and Southern States in 1836, as applied against James K. Polk in 1846. For

a brief look at the origin of the word

and its role in the 1880 campaign, see Peskin,

Garfield, 505-510.

36. James A. Garfield to Henry Root,

October 30, 1880, J.A.G., Ac. 644, Ruther-

ford B. Hayes Memorial Library; Robert

Franville Caldwell, James A. Garfield: Par-

ty Chieftan (New York, 1931), 307. Dana's misgivings proved

correct, and Barnum

and Hewitt appear to have regretted how

easily "they had been duped." Caldwell,

Garfield, 307; and Harper's Weekly, December 4 and 18,

1880; Hayes Scrapbook,

Vol. 81, 36 ff.

Politics of Sinophobia 395

pressed upon the minds of all those who

would be affected by the

policy it declares." Barnum quite

correctly noted that the specific

charges against Philip were

inconclusive. As it transpired, he would

go free. The only individual to serve a

prison sentence in conjunc-

tion with the forged letter was James

O'Brien, alias Robert Lind-

say, and his conviction was for perjured

testimony surrounding the

investigation, not the actual forgery.

He received an eight-year

sentence to Sing Sing on September 14,

1881, and actually remained

incarcerated until August 20, 1886. In

the author's opinion, which

he cannot document, it was probably the

prankster Kenward Philip

who penned the Morey Letter.37

Americans' reactions to the Morey Letter

ranged from the

vengeful to the comic. Determined to

catch the "rascal who

prepared the Chinese letter,"

Republican party worker S.B. Chit-

tenden of Brooklyn offered $5,000 for

the arrest and conviction of

the real Mr. Morey. Mark Twain,

lecturing in Hartford, Connec-

ticut's opera house to an audience of

nearly 2,500 people, admitted

that "I am going to vote the

Republican ticket myself from old

habit...." To no one's surprise and

everyone's delight, America's

preeminent humorist spoofed the

destructive force of electioneering

hyperbole.

I have never made but one political

speech before this. That was years ago.

I made a logical, closely reasoned,

compact powerful argument against a

discriminating opposition. I may say I

made a most thoughtful, sym-

metrical, and admirable argument, but a

Michigan newspaper editor

answered it, refuted it, utterly

demolished it, by saying I was in the con-

stant habit of horse whipping my great

grandmother.38

Republican condottieri on the Pacific

Slope, however, saw no

humor in the matter. Nor did Garfield,

who from the first had sur-

mized that the counterfeit document

"may lose us the Pacific

states." Furious, he sputtered

about "the clumsy villain, who can-

not spell nor write English, nor imitate

my handwriting," and then

snapped, "Hunt the rascal

down." Republican attorneys in the

courtroom, and detectives without,

certainly tried.

On October 25, Jewell telegraphed

Garfield that his statement de-

37. Los Angeles Herald, November

2, 1880; New York Times, December 20, 1881;

Letter from A.V. Byram, Acting Warden,

Sing Sing Prison, to author, February 23,

1965, Ossing, New York. In 1884, when John

Davenport published his book on the

Morey Letter, there was a fresh flutter

of interest in the matter: New York Times,

August 16, 1884.

38. New York Times, October 26,

27, 1880.

396 OHIO HISTORY

nouncing the Morey Letter as a

"bold forgery" was "now being

lithographed ... in time for night mail

for California [I] have ordered

half a million." The San

Francisco Chronicle reassured West Coast

Republicans that their National

Committee had "dispatched a

special car to San Francisco with copies

of the electrotype of the

denial of the Chinese letter.... The

trip across the continent will be

much the fastest ever made by any train."39

Well before the publication of the Morey

Letter, California's

Democratic press had stigmatized

Garfield as pro-Chinese labor.

Stockton's Daily Evening Herald claimed

he would remove "all

obstacles to the immigration,

naturalization, and Christianization of

all the mongolians and other pagans who

may ... come into this

state." The San Francisco

Examiner condemned Garfield as "a

bigot, a Know-Nothing, hater of

Irish," while "always a lover of the

Chinese."40 As on the

East Coast, the response of Pacific Slope

newspapers to Barnum's roorback was

partisan. For example, the

Garfield-allied Sacramento Bee qualified

the epistle as an "alleged

letter," whereas the pro-Hancock Fresno

Weekly Expositor titled

its column, "Garfield on the

Chinese ... Convicted under his own

hand." Possibly it was due to the

fact that California had only twice

voted Democratic in a presidential

contest (1852 and 1856) that

Senator Sargent reassured Garfield,

"The Morey forgery is so well

understood here that it can do no

harm."41

The very day that the story broke, the San

Francisco Chronicle

had impishly featured a summary of

"Garfield and Hancock on the

Chinese Question." The entire

Hancock column was left totally

blank! The next day, with Morey national

news, the Chronicle damn-

ed the letter "A stupid forgery,

... had been put in circulation by

Seven-mule Barnum." In San

Francisco both the Alta and the

Bulletin remained loyal Republican organs. In Los Angeles, the

Daily Herald, which had just justified the late Southern rebellion

"because their rights were openly

violated" and added that "George

Washington was a rebel," eagerly

embraced the Morey Letter. "The

working man who votes for Garfield will

deserve to be excluded

from employment and expelled by

Chinamen," it growled. "The

39. Ibid., October 24, 1880;

Smith, Life and Letters, II, 1041; New York Times,

October 28, 29, 30, and 31, 1880; PG 57,

Marshall Jewell to James A. Garfield, Oc-

tober 25, 1880; San Francisco

Chronicle, October 27, 1880.

40. Daily Evening Herald (Stockton),

October 19, 1880; San Francisco Examiner,

October 19, 1880.

41. Fresno Weekly Expositor, October

27, 1880; Sacramento Bee, October 21,

1880; W. Dean Burnham, Presidential

Ballots 1836-1892 (Baltimore, 1955), 257; PG

57, A.A. Sargent to James A. Garfield,

October 27, 1880.

Politics of Sinophobia 397

Republicans are in the habit of crying

out against the pauper labor

of Europe. They are in favor of the

cheaper coolie labor of China."42

Apparently, a good portion of Denver's

white community felt

threatened by the city's relatively few

Chinese. On November 1,

these few hundred Asians were subjected

to the rule of King Mob.

Clearly, widespread publicity of the

Morey Letter had been a

precipitating element in the social

explosion. On the three days

preceding the riot, Denver's Rocky

Mountain News had featured

large facsimile reproductions of

"GARFIELD'S FAMOUS CHEAP

LABOR LETTER." Although the loss

of life was small, almost the

entire Chinese quarter was gutted.

Newspapers on both the east

and west coasts conveniently laid the

blame on the Morey Letter.

The Los Angeles Herald reported

that "constant repetitions of Gar-

field's letter" displayed in

parade placards had aroused Colorado's

mob. Within Denver, the Rocky

Mountain News voiced no remorse

and continued to chant, "The

Chinese must go."43

Although it would be weeks before the

precise vote was

tabulated, the November 2 election did

not suffer the protracted

verdict that had so crippled Hayes'

"contested victory" four years

earlier. The 1880 Republican candidate

got 214 electoral votes while

his opponent tallied 155. Nevertheless,

Garfield's plurality over

Hancock was but 9,457 votes, the

smallest in American history. Of

all the potential votes, 78.4 percent

were cast, another record not

yet equalled in any American

presidential contest.44

California's Hancock-marked ballots

exceeded those of Garfield's

by fewer than a hundred. Garfield also

lost Nevada, although by no-

where near so thin a margin.45.

Had the Morey Letter been decisive

in the Golden State? Writing to

Cornelius Cole later in November,

President-elect Garfield was

"satisfied that our losses in California

were due to the Morey letter."

Newspaper reactions, on the other

hand, were extremely varied. The Los

Angeles Herald was of the

42. San Francisco Chronicle, October

20 and 21, 1880; Alta California, November

3, 1880; San Francisco Bulletin, October

20, 1880; and Los Angeles Herald, October

12 and 26, 1880. Certainly the Chronicle

bent every effort to remove a pro-Chinese

stigma from Garfield. From October 21 to

election day, it ridiculed the Morey Let-

ter. Afterward, on November 22, it

claimed that copies of the spurious document

"were distributed directly to

servants ... even posted in the kitchens."

43. Roy T. Wortman, "Denver's

Anti-Chinese Riot, 1880," Colorado Magazine,

XLIII (Winter, 1965), 275-91; Los

Angeles Herald, November 2, 1880; Hartford

Courant, November 1, 1880; San Francisco Chronicle, November

1, 1880.

44. Clancy, Presidential Election, 242

ff, notes that "The influence of third parties

on the election was practically

nil." For a recent look at the election, see Allan

Peskin, "The Election of

1880," The Wilson Quarterly, IV (Spring, 1980), 172-81.

45. Statistics vary according to the

source used. These figures are from Petersen,

A Statistical History, 43.

398 OHIO HISTORY

opinion that the "letter did not

unsettle California.... What hurt

Garfield was the business depression on

the West Coast." Essential-

ly in agreement with this view was the San

Francisco Chronicle.

The New York Times disagreed,

convinced that "ignorant and un-

thinking people" had been taken in

by the fraud.46

Garfield did not simply view the Morey

Letter as critical in

California alone. The President-elect

insisted "the forged letter cost

us all the Northern states which we

lost."47 Few if any historians can

accept such a monocausal interpretation;

certainly this author does

not. All of the secondary studies cited

in this paper consider the let-

ter to have been only one of the many

factors that directly affected

the final November vote, a view with

which this author concurs.

What other conclusions can be drawn from

the 1880 presidential

contest and the Morey affair? Shortly

after the election, the San

Francisco Chronicle preferred to lay the campaign to rest with good

humor:

In the last election in New York City

twenty-five Chinese registered voters

cast their ballots. An eastern

journalist thinks they will become a factor in

American politics. It will probably be

in that far distant millennium of the

long-haired reformers, when woman is to

be given all her "rights" including

the privilege of purifying politics.

With a more sober and prophetic arrow,

the Sacramento Bee hit the

political bullseye. Its editor

speculated that perhaps the loss of

California and Nevada might awaken

eastern politicians to the im-

portance of the Chinese question.48

Long before the next presiden-

tial battle, Garfield would fall victim

to an assassin's bullet and the

United

States would let fall its portcullis on Chinese im-

migrants-the former accomplished by a

deranged citizen, the latter

by Congress responding to the wishes of

aroused citizens.

It seems clear that tough-minded Gilded

Age politicians accurate-

ly estimated how volatile had become the

issue of Chinese labor. By

1880 a surprising number of their

toiling constituents were gen-

46. James A. Garfield to Cornelius Cole,

November 22, 1880, Cornelius Cole Col-

lection, Box 4, Research Library,

University of California, Los Angeles; Los Angeles

Herald November

9, 1880; San Francisco Chronicle, November 11 and 13, 1880;

New York Times, November 4, 6, and 10, 1880; and Peskin, "Election

of 1880," 181.

It is worth noting that Hancock later

believed New York City electoral irregularities

(unrelated to the Morey Letter) had

defrauded him of a rightful presidential victory.

See, Almira Russell Hancock, Reminiscences

of Winfield Scott Hancock (New York,

1887), 174-75.

47. Smith, Life and Letters, II,

1042.

48. Ibid.; San Francisco Chronicle, November

27, 1880; Sacramento Bee,

November 6 and 13, 1880.

Politics of Sinophobia 399

uinely alarmed at the Chinese threat as

postulated by the Los

Angeles Herald: "The election of Garfield would be the signal for

the discharge of all white men from

employment by manufacturers

and corporations and substitution of

Chinese coolies."49 With all the

advantages of hindsight, the menace was

more perceived than real.

Yet for Democrats and Republicans alike

at the time, the Garfield-

Hancock contest had powerfully focused

public attention on the

dangers, real or imagined, of cheap

oriental labor. In less than two

years, Congress responded to this

national alarm by legislating

Chinese exclusion.50

49. Los Angeles Herald, October

26, 1880.

50. Congress' May 1882 legislation

suspended Chinese immigration for a period

of ten years and forbade their naturalization. This was

renewed in 1892, and in 1902

Chinese immigration was suspended for an indefinite

period. See, Maldwyn Allen

Jones, American Immigration (Chicago, 1960),

249-63.