Ohio History Journal

|

DIARY OF IMPRISONMENT 51 Saturday 29. Very cold night--heavy frost. No ax to be had. My mess tried to make an apology for last nights treatment, but I told them that I had been with my friend--"out upon such selfishness." Such is the action of a large portion of the prisoners. Cannot send letters through without a C.S. stamp on them. Wrote yesterday to wife but am waiting to get a stamp. Lt Thos Hare gave me a stamp and I put the letter in the box. Slept with Lt Anderson[,] 3rd Iowa[,] in Lt Hare's hut. Not very cold. Sunday 30th Oct 1864 Not up till after sunrise. Two or three shots were fired during the night by the guards but no one hurt. Beautiful day. Capt Dircks & Lt Hare made arrange- ments with guard to let four of us out to night. Started at 8 PM and Capt D and Lt H in advance [with] Capt Smith & I following. We crawled towards the line. When the leading men were within a rod of the line one of the guards fired and shot Capt D through the thigh. We retreated and gave it up for this time. The guards had been changed. Warm and cloudy all night. Monday 31st Oct Cloudy forenoon. Reed a letter from my wife dated Sept 25th[,] one from B W Pease Sept 9th[,] and one from Cousin Mattie B. Whipple Sept 21. All well at home, but no news of Ex[change]. Tuesday Nov 1st 1864 Our mess com[mence]d building a house. Got about half done. Made arrange- ments to escape to night and at half past 11 PM crawled out in co[mpany] with Capts J H Smith 16th Iowa[,] W J Rannells 75th Ohio[,] Jno L Poston 13 Tenn Cav[,] and J L Elder 11 Iowa. Took up our line of march South through the dense undergrowth for about one mile [,] thence S E for about the same distance striking the C[harleston] & C[olumbia] road about two (?) m[ile]s from Columbia. Travelled about 8 m[ile]s further in this road South and at daylight had to stop in a little skirt of timber near the road. It was cloudy all night and comm[ence]d raining about daylight |

|

|

52 OHIO

HISTORY

Wednesday Nov 2d

And rained all day almost completely

drenching us and making us chilled through.

A long day it was and when night came on

we started in and walked about five

miles and at about 11 PM being very

tired and sleepy we turned into a woods on

Henry Bakers plantation [and] built a

fire to warm us. Being very sleepy Capt

Smith [,] Rannells & I lay down on

one blanket and one for a covering[,] we

slept till daylight.

We got up with feet & legs nearly

benumbed with the cold. Finding ourselves near

a house we put the fire out and moved

farther into the timber. Rained all day.

Capt Poston & Elder made a

reconnaissance to our material benefit.

Thursday Nov 3d

Started about dark and taking a by road

came near the Congaree river and building

a fire at the end of an old house dried

ourselves by 11 PM and lay down on the

floor and slept till day break when Capt

Smith and Elder went to reconnoiter the

river for a boat. While they were absent

I found some Persimmons which were

eaten with a relish which a hungry man

[three words unintelligible]. They returned

with a good report. We cooked some rice

in our tin cups and ate our scanty breakfast.

On

Friday Nov 4th 1864

Moved to a thicket and parched some corn

for our subsistance [sic] down the river.

At dusk, as we were going to our old

cabin hiding place, we met three [men ?] of

our escaped officers. At 12 Midnight we

got started in a flatbottomed boat[,] five

of us, and the other three took another

boat. The river being pretty good stage we

got along quite well but had to stop at

daylight about 12 m[ile]s above the RR

bridge which we have to pass in the

night. We were nigh chilled through[,] so we

warmed up and ate a goodly breakfast of

cold chicken and baked sweet Potatoes

and will trust our fortunes to another

day. At sundown we got in our boat and

started running till about midnight when

becoming very cold we landed and built

a fire and warmed up. Lay by till 2 AM

Sunday 6th

We passed easily under the bridge and

found our 3 comrades about a mile below.

Passed on till after daylight when we

landed on an island in the Santee about one

mile below the Wateree.

Built a good warm fire and eat [sic] breakfast.

Toward noon some friends came

up the river and gave us some dinner. At

dusk started on the most beautiful of

rivers of a [moonlit ?] night and made

20 miles passing the Reb obstructions and

deserted battery at one mile and landed

just as the moon was setting at Rice Bluff,

a deserted plantation. Built a good fire

on the [Plateau ?], and all lay down to

sleep but me as watch. This river

abounds with wild ducks and the woods on each

side with raccoons & owls.

Monday 7th

We lay till day break[,] got up, picked

up a Kid, and getting in our boats we went

eight miles and landed in the [cane ?]

on the left bank of the river where we camped

for the day. Dressed our kid and cooked

up a portion in several ways. Baked some

|

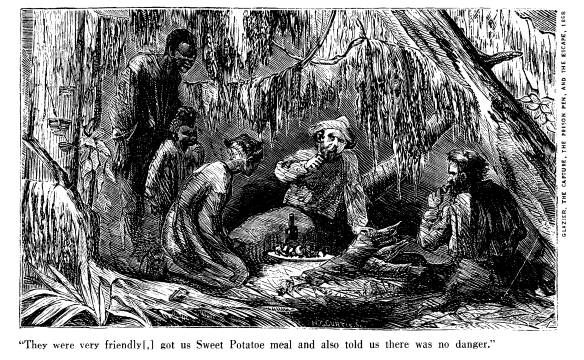

DIARY OF IMPRISONMENT 53 [oat ?] cakes, stewed some turnips and boiled some sweet potatoes, generally faring pretty well. Started at dark [,] came to [Tabs ?] Ferry in 5 miles. Found some negroes who had just ferried a soldier over. They were very friendly [,] got us Sweet Potatoe meal and also told us there was no danger. One old man named Prince was present. He was very glad to see us Yankees. Ran all night till 7 AM Tuesday 8th Nov 1864 When we tied up on an island. Supposed distance run 40 m[ile]s. Roasted the balance of our Kid and made quite a good breakfast of sweet Potatoes and cold Kid. We suppose that we can reach the N[orth] E[astern] RR bridge in about 4 hours run. Started at dark and with a light fog and thick overhead the moon did not mar our progress. Passed the N[orth] E[astern] RR br. at 10 PM (supposed very close), ran 20 m[ile]s and tied up on the Right bank at 12 midnight to wait for the moon to go down so that we could run the Reb Pickets at the Ferry 15 m[ile]s below the RR br. At 2 AM |

|

|

|

Wednesday Started and saw neither Ferry nor pickets. Landed on an island on the left bank at day light after 3 hours run or 5 hours from the bridge. Supposed [distance] 20 m[ile]s. There must be a large plantation opposite, but some distance back. Nothing happened to disturb our quiet little island retreat and after partaking of a hearty supper of sweet potatoes and goat grease we started at dark and passed several plantations on the right bank (the left is all swamp). We stopped at 8 mi[les] and found a potato patch. Dug a bag full. 6 of our party went to the negro quarters and got something to eat and some valuable information. They told |

54 OHIO

HISTORY

us that we had a Battery to pass 5 miles

further down, to go down Chicken Creek

which is 2 m[ile]s long, into South

river, 2 m[ile]s further to Mazyck ferry and a

picket 6 m[ile]s further and to go to

Mullen island a distance of about 40 m[ile]s

where our gunboats visited daily. So on

we started. Passed the Battery without

being seen although it was bright moon

light. Got to Chicken C[ree]k at about

12 m[ile]s and camped on the left bank a

half mile from its head at about 3 AM of

Thursday Nov 10th 1864

Weather pleasant. Secreted our boat in

the cane which lines the banks and had a

good fire built. Slept about 2 hours

before day light. The land is about one foot

above the water and is covered with a

dense growth of trees[,] bushes and grape

vines. The day passed quietly and at

sundown we launched on the C[ree]k. The

Tide being in our favor we glided into

South river in one mile and found it a wide

and beautiful stream with South

Carolina's best rice Plantations on each bank.

Passed Mazyck Ferry unmolested at 5

m[ile]s. Many islands on the left hand and

reached the coast at about 11 PM[,]

dist[ance] about 25 m[ile]s. Visited the wreck

of an iron clad supposing it to be a

steamer but badly landed on a sand bar of

South Island. Built a fire and took a

short nap.

Friday 11th Nov 1864

Saw one of our Blockaders about 6

m[ile]s from the shore. Hailed her but unseen.

Capts Smith, Rannells & Dickerson

tried twice to reach her in one of our boats but

the wind being against them they failed.

It was a fruitless undertaking and I ex-

pected to see them go to the bottom. At

night we went into an old Reb Fort, built

a good fire, roasted some Potatoes and

stayed till

Saturday 12th Nov 1864

When, the day being fair, Capts Smith,

Dickerson & Burke started in one of our

little boats with the determination of

reaching the vessel or perishing in the attempt.

After they had been gone some time we

came across some marines on shore who

belonged to the vessel which proved to

be the Canandagua [sic], Commander Harri-

son. They were glad to meet us but not

more so than we were. We treated them to the

balance of our sweet potatoes and they

in return gave us hard tack & tobacco. At

about 11 AM a boat was seen coming

ashore. [It was from] another Steamer which

proved to be the Flambeau, Lt Ed Cavendy

[,] Commanding. The boat took us off

to the Candagua [sic] where we found

our boats crew had safely arrived. We were

regaled with the best the vessel

afforded and at 2 PM were transferred to the

Flambeau and immediately got under weigh

for Charleston, where we arrived off

at 1 AM

Sunday Nov 13 1864

Got a good breakfast on b[oar]d the

Flambeau and passing the forenoon very

pleasantly we were sent in the Tug Iris

to the Sloop of War, Jno. Adams, Capt

Gown. Took dinner on the Iris and were

transferred to the Tug Gladiolas [sic],

Acting Ensign Napoleon Brighton,

Master[,] and at Sundown we got under weigh

for Hilton Head. Passed out the Morris

Island Channel 3 m[ile]s to Light ship and

then tacked to the S W. Had an excellent

supper on board.

The view from the outside is grand, giving

a view of the Rebel works, ours and

the city.

DIARY OF IMPRISONMENT

55

Providence has in every instance of

danger interposed for our safety. And while

watching for the RR Bridge on [the]

Columbia RR, which we could not pass in

moonlight, we landed before we saw it

and it so happened that we were almost in

sight of it. And when we started a fog

covered the river at the bridge. Such was

the case at the N[orth]E[astern] RR

Br.[,] at the Ferries, and at one Ferry a

Confed Soldier had just crossed before

we arrived.

Monday, 14th Nov 1864

We arr[ive]d at Hilton Head at one AM

this morn and were reported to Rear

Ad[mira]l Dahlgren who sent for us to

take breakfast with him but we were being

provided with an excellent breakfast on

the Gladiolas, after which we steamed up

to the Flag ship and were very agreeably

entertained by the Adl. who ordered us

to be clothed by the Naval Dept. and

then sent us to Gen Foster at Hilton Hd who

reed us very gladly and regaled us with

a repast & very pleasant chat [,] with some-

thing good to take--apples & grapes.

He ordered that we be paid 2 mo[nths pay]

and have Transportation to New York on

to morrow. We called on Maj Jos [More ?]

who paid us two mo[nths] pay for July

& August amounting to for me 233 doll[ar]s.

My Serv[an]t black--John, 5 ft. 6 in.

high.11 Tax $3.50, making Capt[ain's]

pay

120$.

I learned that a box went up to Columbia

for me on the 3 of this mo[nth] and that

a letter with 20 doll[ar]s in gold went

up on the 26 Oct. I wrote to Lt. Fairfield to

use the same, and gave him a sly hint

what route I came.

We found the Fed officers here could not

do too much for us. Every favor and kind-

ness asked or needed was extended to us.

A Steamer or cat boat with an officer

and men to work it[,] as Admiral

Dahlgren said to day "You shall have a steamer.

You shall not go in a row boat."

We put up at the Port Royal House.

Tuesday 15th Nov.

Had a good nights rest in a good clean

bed[,] with good fare, and this morning

turned out to make some purchases-- a Vest 6.00, Portmanu [sic] [1.00?],

4

Collars .20, Pens .35, Hat 7.00, Hdkf.

.75�, Gloves .80�, Chessmen $2.00, Tobacco

.30�. For Hotel bill 2.50[,] Apples

.20�. [Tub ?] to N. Y. 8.00. Total $29.10.

Went on board the Fulton at 2 PM and got

underweigh at 4 PM. Slept well to night.

Wednesday 16th

All well. Fine weather and smooth sea.

We have very pleasant times there being

but few passengers. Capt Smith has the

military command of the vessel. At noon

we were off Wilmington[,] N C about 60

m[ile]s from the coast. Pleasant night.

Thursday 17th Nov.

Passed Cape Hateras [sic] at 3 AM

this morning. Sea a little rough. Wind changed

to Eastward so that we can use a fly

sail.

Slightly colder. At noon off Roanoke

island. Prospects to be in N Y by 2 PM

to-morrow.

Yesterday I wrote a letter to Mrs E M

Coffin of Nantucket and to day made my

report to Adjt Gen U S A, to be sent on

arrival in N Y City.

By request of Maj Gen Foster we made a

statement regarding the treatment of our

56 OHIO

HISTORY

officers in Reb prisons and signed the

same officially. This was to be sent to War

Dept.

Friday Nov 18th 1864

Weather a little rough. The latter part

of the night the Jersey Coast in sight with

several vessels on either hand. Cool and

rainy. Feel quite well. Passed around

Sandy Hook. Two vessels aground on our

Starboard quarter. Passed the Forts Hamil-

ton on L[ong] I[sland] and Old Fort

Layfayette [sic] on the Staten I[sland] side and

landed at Pier 36[,] N[orth] River. Went

to PM Genl Hays in St Marks Place.

He refused to give us transportation

west so Capt Smith and I[,] after getting dinner

at the Tremont House on Broadway, went

to the Jersey City Ferry at the foot of

Duane St, bought Tickets for Home. I pd

23 doll[ar]s to Cin[cinnati].

Started at 5 PM on the Erie RR. Got to

Elmira at daylight.

To N[orth] East [near Erie,

Pennsylvania] at dark[,] Cleveland at 9 PM [the] 19th.

Got supper and at 12 midnight Capt Smith

took the Chicago train at Crestline and

I arrived in Cin at 10 AM Sunday, [the]

20th, having dropped a letter at Milford

for E A Parker and one for J F Avery to

let my family know of my arrival. Took

dinner at the Indiana House and went to

Mr. C. W. Bunkers and stayed till Monday.

Nov 21st 1864

When I went home per the

"Buss" where I arrived at 8 PM and found all well and

some what surprised to find the dead

alive, the Captive Free, and our Prayers

answered. God be praised.

THE EDITOR: Louis Bartlett is a teacher

in the New York public school system. He

holds an M.A. degree in history from

Columbia

University, where he has also been

working on

his doctorate.

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS REMBRANDT and |

|

|

THE OHIO HISTORICAL SOCIETY by WILLIAM C. KEENER |

|

A FEW MONTHS ago the Metropolitan Museum of Art shocked the public, and certainly surprised the museum world, by paying the remarkable sum of $2,300,000 for Rembrandt's painting of "Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer." It was an historic occasion and one filled with more than its share of drama. So- cialites, art dealers, critics, collectors, and museum people gathered for the sale in the austerely furnished main auction room at Parke - Bernet Galleries, New York, while less fortunate ticket holders were dispersed to nearby quarters and forced to participate via closed-circuit television. Not a few prominent and no- ticeably irate public figures were turned away. Excitement ran high, for although other fine paintings were to be sold, the Rembrandt commanded the attention-- and aroused the speculation--of every person present. Parke-Bernet auctions are especially |

|

well managed and move very quickly. Tension mounted steadily as the monoto- nous voice of the auctioneer droned the opening bid on the "Aristotle" -- one million dollars. Raised hands or subtle nods and other obscure bidding devices rapidly raised the price to the successful pinnacle, the highest price ever paid for a painting. In the weeks that followed, conscienti- ous reporters solicited opinions on this amazing purchase from all classes of peo- ple from cab drivers to bank presidents, and many thousands who had never set foot in a museum trekked to the Metro- politan to contemplate "Aristotle." For many it was the greatest painting they had ever seen; it evoked an emotional and aesthetic response of unequaled mag- nitude. But to almost everyone who saw it or read about it, it posed two nagging questions--why did it cost so much, and why did the museum buy it? |

|

58 OHIO HISTORY |

|

It is not our purpose here to discuss the Rembrandt's uniqueness, quality, or aesthetic appeal, nor the wisdom of the Metropolitan Museum's decision to buy the picture. But this single event that so effectively captured the imagination of the public, also focuses attention on those two legitimate questions that go to the heart of museum and historical society acquisition policies. They are the ques- tions that any curator must ponder as he considers an object for acquisition. He does so, however, with a conception of the museum's purpose that is often much different from that of the casual visitor. The first question is easier to answer, or, perhaps, to understand, than the sec- ond. At the same time that the American people have become increasingly appre- ciative of the past, their affluence has encouraged competition in the acquisition of those objects that represent significant expressions of the cultural heritage of their civilization. As a result of this ri- valry, which is dominated primarily by private collectors and certain museums, the prices of the rare and distinctive pieces of times gone by have risen sharply, sometimes, it seems, as in the case of the Rembrandt painting, to fan- tastic heights. The fact is that many of the relics of former periods, such as art objects, household furnishings, orna- ments, textiles, tools and implements, publications, and manuscripts, have mone- tary value. The museum that would ac- quire any of them must pay for them or receive them by gift, and if they are given, the donor may be credited with their monetary value. The answer to the second question is involved with the very purpose of the institution known as the museum. Con- trary to a still widely held opinion, mu- seums are not, or should not be, large, dusty depositories for curios. The modern museum serves many masters and many causes. It must accommodate the needs |

|

of the scholar, the student, the collector, the casual visitor--and posterity. Each of these groups, and others, requires par- ticular attention, and it is the duty, indeed the obligation, of the institution to develop its collections so that all may be served. Obviously, the purpose of the collecting program of a museum must be somewhat broader than the aims of the private collector. He can indulge a serious inter- est, a whim, or an idiosyncrasy to the extent of his needs or of his wealth. His responsibility is only to himself. This is not to say that many great private col- lections have not been formed, but to point out that the private individual has no obligation to develop his collection to meet any requirements other than his own. The museum, on the other hand, must consider its acquisitions, both indi- vidually and collectively, in terms of pub- lic or general use. An object, whether it is a Rembrandt painting or a stoneware crock, has a va- riety of uses in a museum collection. First, and perhaps most important, the museum item is a fact; it is a physical document of a moment, of a taste, of a craft or an industry, of a culture, and of an age. It can be used, much as a manu- script is used, as historical evidence. Fre- quently, the object is the only form of evidence that sheds light on a particular facet of social or cultural history, or, when used in conjunction with other types of documentation, it provides a broader understanding of a particular subject under consideration. Archaeolo- gists have long understood and made effective use of artifacts as documents, and some modern historians have devel- oped a similar appreciation in recent years. In the same context, a group of like or related objects can prove even more use- ful in developing documentation in depth. Just as a diary or collection of letters |

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS 59 |

|

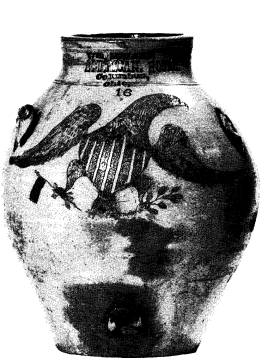

provides a deeper insight than a single document into the thoughts and actions of an individual, so also a collection of fire- arms, for example, gives a clearer view than a single weapon of the development of the military, protective, and hunting techniques and abilities of a given his- torical period. The object is presented to the public generally, however, as an interpretive piece in a museum's exhibition. Here the full impact of its aesthetic and visual ap- peal can be combined with its documen- tary qualities to illustrate a particular point or to delineate a whole culture. Its exhibition is the ultimate moment of truth for the object, for here, transported through time to the present, it speaks of its own environment, of the events in which it participated, and, to some extent, of the men who made and used it. The degree to which it is successful in com- municating its message depends upon the merit of the object and upon the ability of the museum to display it. The acquisition program of the Ohio Historical Society is based upon its obli- gation to fulfill these needs of preserving documentation of our culture and, through the documentation, of interpret- ing our past. Each object considered for the historical collections, therefore, is evaluated in terms of its significance as a document, its intrinsic merits, its impor- tance to the collections, and its value to the Society's exhibition programs. The object, to be acceptable, must also meet high standards of quality and condition. The large stoneware crock pictured on the cover provides an excellent illustra- tion of these considerations for acquisi- tion in practice. It is not difficult to visualize this massive container gracing the premises of the American House in Columbus during the mid-1840's, nor does a finer means exist for helping to develop an understanding of the early pottery craft in the Ohio Valley. Its pro- |

|

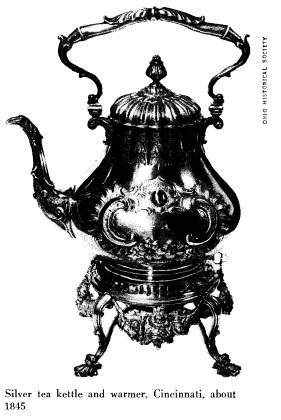

venience is well authenticated by marks impressed on the body. In form and dec- oration it is one of the finest examples of stoneware in existence. This piece is also a desirable addition to the Society's ex- tensive collection of salt-glazed stoneware, and it clearly shows the development of the technique of scratched or incised dec- oration. Finally, it can be utilized in a variety of exhibitions. It is apparent, in this instance, because of its singularity, that the significance and quality of this object override its defective condition. The fact that the handles of this unique crock are broken and missing does not detract from its ability to fill all of the acquisition requirements. Another recent addition of consider- able importance to the Society's collec- tions is the silver tea kettle and warmer illustrated here. It was made and sold by |

|

|

|

|

Edward and David Kinsey of Cincinnati about 1845 and is one of the few extant marked hollow pieces of Ohio silver. The Kinseys were active separately and in partnership for several decades before the Civil War and were perhaps the most prolific silversmiths in the state. Their work on this particular piece can hardly be judged by comparison with that of the great American silversmiths of the eigh- teenth century, but within the context of its period, it excels in craftsmanship and restrained ornamentation, not often found in the early Victorian years. It is an im- portant document, not only of the craft of silversmithing but also of the taste and furnishings of its period as well. While the significance of a single ob- ject is sometimes difficult to appreciate, it generally takes on added meaning when it is viewed along with similar objects and also with objects made from the same ma- terial or by the same method. One of the goals of the museum is to build collec- tions of comparable objects in order to achieve an understanding of the whole production of a particular category. On occasion a museum finds itself in a for- tunate position to acquire a large group of similar or comparable materials for its collections at one time. Usually these are selected from a major private collection that has been assembled by an informed and discerning collector over a period of years. Recently the Ohio Historical So- ciety was privileged to make a selection of more than 350 pieces of American |

|

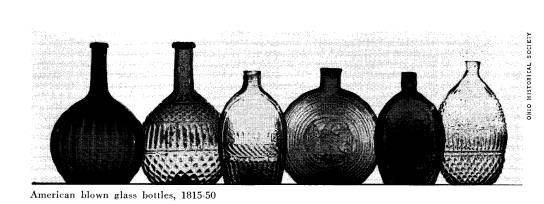

blown glass and blown molded glass from the collection formed by the late George S. McKearin, an eminent collector of early American glass and an authority on that subject. This acquisition swelled the Society's holdings in this important field to approximately one thousand items. This fine collection helps to document the historical impact of glassmaking on the economy of the state and on the con- sumer habits of its citizens. As early as 1815 a small factory in the Zanesville area was producing bottles, tableware, and window glass for local consumption, and within a few years similar enterprises sprang up at Kent, Ravenna, Mantua, and Cincinnati. Calling upon experienced craftsmen who had been trained in the East and in the flourishing Pittsburgh factories, the Ohio firms maintained the production of a steady stream of blown- glass tableware and containers through- out the first half of the nineteenth cen- tury. With the discovery of glass-pressing techniques, an even greater volume of production literally swamped the glass market after mid-century. On this page is a picture showing sev- eral examples from the collection. At the left is an amber, broken-swirl globular bottle, typical of thousands that were made between 1815 and 1830 as contain- ers for spirits and a variety of household liquids. Beside it are two blown three- mold pieces--a bar bottle and a flask-- which were made at Kent during the rage for this type of imitation of the more ex- |

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS 61 |

|

pensive cut glass. One hundred and twelve patterns and fifteen colors produced by this remarkable technique are represented in the collection. Flanking these pieces on the right are three of the historical, or figured, flasks that became so popular in the 1830's and 40's. The concentric-ring eagle flask is one of today's great rarities among the extant products of the New England Glass Company, of Massachu- setts. The other two were made at Zanes- ville by Murdock-Cassel and Shepard. These are but three of more than two hundred flasks in the collection. These objects help to illustrate the kind of effort that the Society is making to de- velop its collections. It is designed to meet a variety of purposes and to serve a number of publics, and it is applied to a number of collecting areas, including furniture, textiles, household utensils and furnishings, paintings, prints, firearms, tools, hardware, and metal products. It is an effort that must continue unabated and on an increasing scale if the Society is to meet its obligations to the citizens of Ohio. THE AUTHOR: William G. Keener is the curator of history of the Ohio Historical Society. |

|

|

|

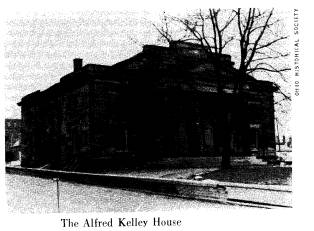

NEWS and NOTES THROUGH the efforts of a group of Colum- bus citizens, organized as the Kelley House Committee, Inc., and the Franklin County Historical Society, the famous Alfred Kelley mansion, located at 282 East Broad Street, has been carefully dis- mantled and removed to Franklin Park, where it is to be reconstructed and re- stored. At Franklin Park the stonework of each wall has been laid out on the ground in the same position it had vertically. Each of the three thousand stone blocks in the structure was marked to indicate its precise position. Some three hundred photographs were taken, and careful measurements and drawings were made, to record all exterior and in- terior architectural features. Walter L. Davis, construction super- intendent of the Ohio Historical Society, and Cyril H. Webster, who was on the staff of the Society as building superin- tendent of the Ohio State Museum before his retirement in 1958, supervised the dismantling and recorded the structural and architectural details. Members of the Columbus chapter of the American Institute of Architects served as con- sultants. The Alfred Kelley House was one of the largest and finest homes built in the Old Northwest at the height of the Greek Revival period. Erected in the 1830's, it was then the most imposing house in Columbus, and was until its dismantling one of the few examples of Greek Re- |

|

vival domestic architecture still standing in the heart of a large city. Its design is one of dignity and simplicity, featuring four Ionic porticoes and an unusual, if not unique, masking stepped parapet. The structure was built of Ohio standstone, probably brought to Columbus by canal boat. The house had many important his- torical associations. As the home of one of Ohio's ablest statesmen from 1838 to 1859, it was the center of hospitality for all important state and local political leaders. Sixty delegates to a convention in 1840 were entertained there at the same time. Alfred Kelley was one of the "fathers" of the Ohio canal system and supervised much of its construction. He became the architect of Ohio's financial and tax structure during his service in |

|

|

the general assembly and on the canal commission. At mid-century he turned his energies to the introduction of the railroad to Ohio. THE Ohio Historical Society will hold its seventy-seventh annual meeting at the Ohio State Museum, Columbus, Friday, April 27. The theme of the meeting is to be the Early American and Ohio Decorative Arts, and a special feature will be the opening of a new decorative |

|

NEWS AND NOTES 63 |

|

arts gallery at the Museum. The luncheon for members of the Society, guests, and officers and staff will be served in the galleries of the Arthur C. Johnson Audi- torium. RAYMOND S. Baby, curator of archaeology of the Ohio Historical Society, has been appointed by the Society for American Archaeology to participate in its abstract- ing program. As collaborator of the latter organization he is charged with preparing abstracts of all current pub- lished materials that concern the archae- ology of the Ohio area. The abstracts are to be published in the series known as Abstracts of New World Archaeology, be- ing prepared and issued by the Society for American Archaeology. Two volumes of this series have appeared to date. TWO new publications on the general sub- ject of Ohio and the Civil War have been issued by the Ohio Historical Society and the Ohio State University Press for the Ohio Civil War Centennial Commis- sion. They are Ohio Negroes in the Civil War, by

Charles H. Wesley, president of Central State College, and Ohio Forms an Army, by

Harry L. Coles, professor of history at Ohio State University. Other publications in this series, which is being prepared under the direction of the Advisory Committee of Historians of the centennial commission, are Ohio Troops in the Field, by Edward T. Downer; The Ohio Press in the Civil War, by

Robert S. Harper; and Ohio Politics on the Eve of Conflict, by Henry H. Simms. Future publications scheduled to appear during the coming year are Ohio's War Governors, by

William B. Hesseltine; Ohio Military Prisons in the Civil War, by Phillip R. Shriver; Ohio Agriculture During the Civil War, by Robert L. |

|

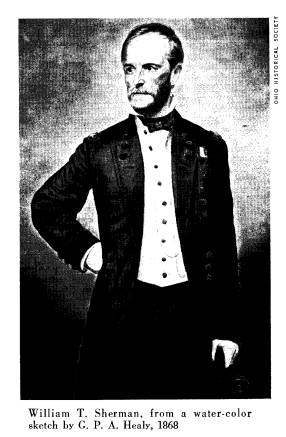

Jones; The Sherman Brothers and the War, by

Jeannette P. Nichols; Ohio Churches and Religion During the Civil War, by

Richard W. Smith; Cincinnati and the Civil War, by Louis L. Tucker; Vallandigham and the Civil War, by Frank L. Klement; Lucy Webb Hayes Views the Civil War, by Mrs. Ralph Geer; The Bounty System in Ohio Dur- ing the Civil War, by Eugene C. Mur- dock; Ohio Colleges in the Civil War, by G. Wallace Chessman; and Gunboats on the Ohio During the Civil War, by Robert Seager, II. The members of the Advisory Com- mittee of Historians are Thomas L. LeDuc, Oberlin College; Paul McStall- worth, Central State College; Paul I. Miller, Hiram College; Eugene C. Mur- dock, Marietta College; Virginia B. Platt, Bowling Green State University; James H. Rodabaugh, Ohio Historical Society; Robert Seager, II, Denison University; Phillip R. Shriver, Kent State University; Henry H. Simms, Ohio State University; Duane D. Smith, University of Toledo; H. Landon Warner, Kenyon College; Harris G. Warren, Miami University; Harvey Wish, Western Reserve Univer- sity; and Everett Walters, Ohio State University, chairman. The publications may be purchased or ordered from the Ohio Historical Society, 1813 North High Street, Columbus 10, Ohio. WILLIAM T. Utter, professor of history at Denison University, Granville, since 1929, died suddenly in a Newark, Ohio, hos- pital, January 12, 1962. Dr. Utter is re- membered as a contributor to and warm supporter of the work of the Ohio His- torical Society. He was the author of The Frontier State, 1803-1825, which was Volume II of the six-volume History of the State of Ohio, published by the |

|

64 OHIO HISTORY |

|

Society between 1941 and 1944. In the early 1950's he served as a consultant historian to the Society on improvements at Zoar, Adena, and the William T. Sher- man Birthplace. His most recent major publication was a book entitled The Story of an Ohio Village, a history of Granville issued in 1956. At the time of his death he was serving as chairman of the Ohio His- torical Advisory Committee of the Gov- ernor's Committee for Commemorating the Sesquicentennial of the War of 1812. Dr. Utter was the recipient in 1957 of an honorary life membership in the Ohio Historical Society. THE annual meeting of the Ohio Academy of Medical History will be held in Cleve- land, Saturday, April 28, 1962. The morning session is scheduled at the West- ern Reserve Historical Society, the lunch- eon and afternoon session at "Gwinn," the former Mather estate, located on the shore of Lake Erie at 12407 Lake Shore Boulevard. THE Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio, Cincinnati, has announced plans for a new building. For many years housed in a section of the University of Cincinnati Library, it will erect its new structure as an addition to the Cincinnati Art Museum. The society will house its valuable collections in air-controlled sec- tions of the new quarters, enjoy modern reading rooms and offices, and have access to lecture hall and exhibition facilities. The January issue of the Bulletin of the Historical and Philosophical Society is a special edition devoted to the subject "Germany and Cincinnati." Among its nine articles and notes are an article on "The Germans of Cincinnati," by Carl Wittke, vice president of Western Re- serve University, another on "German |

|

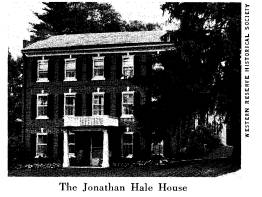

Philosophy in Nineteenth Century Cin- cinnati," by Loyd D. Easton, chairman of the department of philosophy at Ohio Wesleyan University, and a third on "Some Architectural Aspects of German- American Life in Nineteenth Century Cincinnati," by Carl M. Becker, associate professor of history at Sinclair College, Dayton, and William H. Daily, a Dayton architect. THE Jonathan Hale Homestead, a museum of the Western Reserve Historical Society located near Peninsula, Ohio, is the sub- ject of a book recently published by the society. Written by John J. Horton, an |

|

|

associate for research of the society, the 160-page volume is entitled The Jonathan Hale Farm: A Chronicle of the Cuyahoga Valley. Jonathan Hale came from Connecticut to the Western Reserve in 1810. There he settled on the farm, which remained in the possession of the Hale family until 1956. In that year the Western Reserve Historical Society inherited the property from Miss Clara Belle Ritchie, who in- structed the society in her will to "take the necessary steps to establish the Hale Farm and buildings thereon as a museum for the display of books, paintings, furni- ture, household goods, farm and house- hold implements, china, silver, plate, ornaments, and similar objects, belong- |

|

NEWS AND NOTES 65 |

|

ing to the period and culture of the Western Reserve." The Hale house, a large three-story brick structure, built about 1827, has been restored and furnished in period by the society and opened to the public. Open also are the old sheep barn, which houses a museum of tools and imple- ments and methods of farming, and the Forge Barn, which is a museum on the skills and crafts of the early settlers of the Western Reserve. TWO significant research projects in Ohio history were given financial assistance by the American Association for State and Local History at its meeting in Washington, D. C., December 29, 1961. They were a study entitled "Internal Im- provements and Economic Change in Ohio, 1820-1860," by Harry N. Scheiber, assistant professor of history, Dartmouth College, and "A History of the Society of Separatists of Zoar," by Edgar B. Nixon, editor, the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library. Working under a Social Science Re- search Council Fellowship, Dr. Scheiber spent the year 1959-60 pursuing his re- searches for his study in the collections of the library of the Ohio Historical So- ciety. Dr. Nixon, a former resident of New Philadelphia and a descendant of Zoarites, has also worked in the Society's library in its extensive holdings of Zoar materials. A total of ten grants were made by the American Association for State and Local History at its December meeting. Such grants are made each year by the association as a part of its program to stimulate research and publication in state and local history. THE Fifth National Assembly for the centennial commemoration of the Civil War will meet in Columbus, May 4-5, |

|

1962. Invited to Ohio by the Ohio Civil War Centennial Commission and the Ohio Historical Society, the assembly will bring to the state capital the officers of the national Civil War Centennial Commission, representatives of state com- missions and historical societies through- out the country, and the nation's leading Civil War historians. Heading the federal delegation will be Allan Nevins, newly appointed chairman of the national commission, and James I. Robertson, Jr., the new executive di- rector. A feature of the program of the as- sembly will be the exhibition of "The General," the famous railroad engine of the Andrews Raid, popularly known as "The Great Locomotive Chase." The en- gine is being sent to Columbus by its owner, the Louisville and Nashville Rail- road. THE Western

Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, announces that negotiations are under way for the removal and dona- tion of the Thompson Auto Album, a mu- seum of antique automobiles and air- planes, to the society. Thompson Ramo Wooldridge, Inc., now owns the collec- tion, which it displays in a building at East 30th Street and Chester Avenue, N.E., Cleveland. The architectural firm of Charles Bacon Rowley & Associates, Inc., which designed the Norton addition to the historical so- ciety's property several years ago, has been engaged to prepare plans for a sepa- rate building to house the auto album. The automobile museum was started in 1937 by Thompson Products, Inc., the predecessor of Thompson Ramo Wool- dridge, Inc., under the leadership of the firm's president, Frederick C. Crawford. EUROPEAN backgrounds

of western civili- zation are to be stressed in a fifty-five day, twelve-country, group study-tour of |

|

66 OHIO HISTORY |

|

Europe this summer, sponsored by Case Institute of Technology, Cleveland. The tour will leave New York by non-stop jet on June 30 and arrive in Amsterdam on July 1. From there it will visit his- toric and contemporary sites and cities in Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, Ger- many, Switzerland, the principality of Liechtenstein, Austria, Italy, Greece, France, Monaco, and England. The tour instructor and supervisor will be Dr. Stanton Ling Davis, associate pro- fessor of history at Case Institute, who has directed summer study-tours in Europe for ten years. Case Institute will grant six semester hours of credit to those who wish it and meet the customary academic requirements. Teachers may use the tour and Professor Davis' accom- panying course in the European Back- ground of Western Civilization to meet in-service credit requirements. For further information write to Pro- fessor Stanton L. Davis, Department of Humanities and Social Studies, Case In- stitute of Technology, Cleveland 6, Ohio. THE Presbyterian

Historical Society, lo- cated in Philadelphia, announces that it will microfilm any paper or thesis which the society "considers to have sufficient interest for the study of the history of Presbyterianism or material relating to Presbyterianism." The microfilming of any item will be done at no expense to the author. "This service," the society states,

"is intended primarily for the reproduction of graduate theses, seminar papers, re- search projects, scholarly manuscripts, and other results of original research." The society proposes to make the micro- film available to any interested persons and institutions. Authors are urged to correspond with the society at 520 Witherspoon Building, Philadelphia 7, Pennsylvania, before send- ing manuscripts. |

|

THE American

Association for State and Local History, which has had its offices at the State Historical Society of Wis- consin, has moved to new quarters at 151 East Gorham Street, Madison 3, Wis- consin. The association will occupy the second floor of a brick building in a sec- tion of fine old houses, many of which have been converted to business use. It was formerly the residence of a prominent Madison family. The association, which was organized to promote interest and work in state and local history and to serve as a clear- ing house of information for historical societies and agencies, has greatly ex- panded its activities under its present di- rector, Dr. Clement M. Silvestro. The association issues a monthly magazine entitled History News and also Bulletins that are generally aimed at assisting local societies in organization, administration, and operations. Among the latest Bulle- tins are A

Guide to the Care and Admin- istration of Manuscripts, by Lucile M. Kane, and The Management of Small His- tory Museums, by

Carl E. Guthe. Membership in the association is open to all interested persons. It particularly welcomes local historical societies and their officers. THE National

Archives is issuing a series of small pamphlets to describe its various collections and explain its services to the American people. Of several that have particular interest for Ohioans are three entitled as follows: Pension and Bounty- Land Warrant

Files in the National Archives; Genealogical Records in the National Archives; and Age and Citizen- ship Records in the National Archives. For copies of these and other pamphlets, write to The National Archives, Wash- ington 25, D.C. |

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS THE LIBERTY LINE: THE LEGEND OF THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD. By Larry Gara. (Lexington: University of Ken- tucky Press, 1961. xi+201p.; index. $5.00.) "Although the underground railroad was a reality, much of the material relat- ing to it belongs in the realm of folklore rather than history. . . . Most legends have many versions, and the story of the underground railroad is no exception. Few people can provide details when asked about the institution. Specific in- formation is usually crowded out by vague generalizations. The underground railroad is accepted on faith as a part of America's heritage" (p. 2). The above quotation gives the cue to Professor Gara's monograph. First, he examines the legend. Most of the slaves were longing for freedom and large num- bers of them sought it in the "Promised Land of freedom." Abolitionists, bravely facing danger and hardship, perfected a vast and methodical network known as the Underground Railroad, by means of which the slave attained his objective of freedom. Innumerable tunnels and sta- tions existed, and secrecy in operations was essential, since the conductors often found their lives endangered as a result of their efforts. A part of the tradition, too, is the essential morality of the New Englanders and the Quakers as opposed to the wickedness of the southerners. The author examines also the factors in the persistence and strengthening of the |

|

legend. Prior to the Civil War, stories of escaping slaves and their benefactors were repeated, oftentimes with embellishments. Abolitionists magnified the numbers of fugitives so as to suggest the unstable nature of the southern institution and to show the extent to which they were help- ing to undermine it. Southerners exag- gerated the numbers escaping in order to show the magnitude of their property losses and the extent of the concerted efforts in the North to violate a provision of the constitution. After the war, count- less reminiscences of elderly people, ac- cepted in uncritical fashion by numerous historians, perpetuated the legend. Professor Gara utilizes a variety of sources in his revisionist study, and from them successfully demonstrates that too much that is fanciful has been associated with the Underground Railroad. He feels that most slaves preferred freedom to servitude, but looked upon their existence in a practical way, and hence did not at- tempt escape. Those who did, frequently did not go to the North, which, with its considerable degree of race prejudice, was not as much a land of freedom as it was pictured. He points out that many fleeing slaves traveled long distances and long periods of time without assistance, and hence actually were the heroes to a greater extent than those who assisted them. Organized assistance was confined mostly to localities, and widespread se- crecy did not exist. The author feels that Professor Wilbur |

|

68

OHIO HISTORY |

|

H. Siebert of Ohio State University, through his writings based partly on un- critical acceptance of abolitionist evidence at a time when the psychological atmos- phere lent itself to glorification of the Underground Railroad, did much to per- petuate the legend. An examination of his writings and of many others that follow the same line leads to the conclusion that the sources used in producing them were not entirely authoritative. HENRY H. SIMMS Ohio State University THE MIDWEST: MYTH OR REALITY? Edited by Thomas T. McAvoy, C.S.C. (Notre Dame, Ind.; University of Notre Dame Press, 1961. vii+96p. $3.50.) This record of a symposium held at the University of Notre Dame in April 1960 examines the Midwest from sociological, economic, political, and cultural angles. The six panel members deal with "the chief criticisms of the Midwest in the second half of the twentieth century"-- questions of the region's identity, its attitudes, its problems and prospects. Historically there has been a definite and distinctive Midwest. It began as the West, then it was the Northwest, and by 1850, when the West moved beyond the Missouri, it became the Midwest. Under all these names it was distinct and differ- ent, newer, more energetic, and more adaptable to change than the older sec- tions of the United States. "Europe," said Ralph Waldo Emerson in the 1840's, "reaches to the Alleghenies; America stretches beyond." Lord Bryce called the Midwest the most American part of America. Is the Midwest, a century later, a sepa- rate entity? To this underlying question the panelists answer that it is less sepa- rate but still an entity. Professor Russel B. Nye finds the region still capable of protest; Professor Jay Wylie, with the help of statistics, demonstrates the integ- rity of its economy; Father Thomas McAvoy points out the melding of Yan- |

|

kee, southern, and immigrant strains in the Midwest mind, a melding which pro- duced a combination of tolerance, indi- vidualism, and practicality. This con- siderable claim could probably have been documented if Father McAvoy had had more space than his twenty-two pages. The liveliest essay comes from a journ- alist, Donald R. Murphy of Wallace's Farmer, who

discusses the dilemma of the Midwest farmer who tries to beat declin- ing prices by increasing production, which depresses prices further. He makes a persuasive plea for the family farm, a sociological aim which in the face of eco- nomic realities is easier to agree upon than to realize. In his essay on midwestern literature John T. Flanagan provides a balanced and enlightening survey of a big subject. He stresses the realism of Midwest writing, its use of the vernacular--as in Mark Twain, Kirkland, Eggleston, and Ade-- and its healthy criticism of the status quo in both rural and urban life. In a final brief comment John T. Fred- erick brings the Midwest into the clearest focus. He sees the region's diversity, its continuing processes of change, and its unawareness of its own identity. To help people examine their society is the pur- pose of a book like this. WALTER HAVIGHURST Miami University THE WELSH IN AMERICA:LETTERS FROM THE IMMIGRANTS. Edited by Alan

Con- way. (Minneapolis: University of Min- nesota Press, 1961. 341p.; bibliography and index. $6.00.) AMERICA'S POLISH HERITAGE: A SOCIAL HISTORY OF THE POLES IN AMERICA. By Joseph A. Wytrwal. (Detroit: Endur- ance Press, 1961. xxxi + 350p.; bibli- ography, appendix, and index. $6.50.) These two volumes illustrate the ex- tensive research which is currently being done on the contributions of various immigrant groups to American life. In each case the author has facility in the |

|

BOOK REVIEWS 69 |

|

language used by the people involved, an advantage not generally claimed by present-day scholars. The first volume contains 197 letters, most of them originally written in Welsh, edited by a lecturer in American history at the University College of Wales, Ab- erystwyth, Wales. The letters are ar- ranged chronologically and geographi- cally, beginning with those which tell of the voyage across the Atlantic. Additional letters are from the farming areas of New York, Pennsylvania, and various midwestern states; from Welsh settle- ments on the Great Plains; from the coal mines and the iron and steel produc- tion regions of Pennsylvania and other states; from the mines of California and Colorado; and from the Mormon com- munities of Utah. Ohioans will be espe- cially interested in letters from Granville, Paddy's Run (Butler County), Van Wert County, and other areas of Welsh settle- ment. Many of the letters are written in a tone of deep discouragement, but those from Ohio are universally optimistic. The volume on the social history of the Polish-Americans fills a very large gap. The author, who knows well the Polish-American milieu, has his doctorate from the University of Michigan and during the past year has taught at the University of Detroit. He has used li- braries in Poland and in various centers of Polish culture in the United States. There are chapters dealing with the Old World historical background, Polish mi- gration in colonial times, migration prompted largely by political motivation before 1870, and that stimulated espe- cially by economic causes after 1870. Extensive treatment is also given to the Polish National Alliance, to the Polish Roman Catholic Union, to Polish-Ameri- can participation in each World War, and to other phases of Polish-American life. The author states in his introduction: "It is still correct that the history of immigration in the United States, espe- cially in its relation to other phases of |

|

history, has been, comparatively speak- ing, sadly neglected in detail and in general" (p. xxvii). In view of the vast amount of research published regarding German, Scotch- Irish, Swedish, Norwegian, and other groups in the United States, this may well be an overstatement, more true of Polish-American groups than some others. Indeed, the author's extensively docu- mented chapters are revealing as to the great strides which have been made in research relating to Polish-American com- munities and institutions. Ohioans will be interested in the numerous references to Ohio areas. The author exhibits a firm intention to be objective, but he certainly minimizes the importance of the Polish National Catholic Church, which sepa- rated from Roman Catholicism in the United States. He states that this or- ganization has about 75,000 members (p. 103), but the World Almanac, 1961 (p. 696) places the membership at 282,411. FRANCIS P. WEISENBURGER Ohio State University SAMUEL ROBERTS: A WELSH COLONIZER IN CIVIL WAR TENNESSEE. By Wilbur S. Shepperson. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1961. xi + 169p.; illustrations, appendices, bibliography, and index. $5.00.) The story of Samuel Roberts (1800- 1885) illustrates many of the problems, frustrations, and rewards of European immigrants in the last century. The Welsh preacher, journalist, and reformer decided in 1857 to move to the United States, where his cousin, William Bebb, had already been governor of Ohio. In eastern Tennessee he established a colony as a refuge for his oppressed fellow- countrymen from Wales. Reluctance of the Welsh to migrate, the preference of those who did for Ohio, and other diffi- culties too great to be overcome led Roberts to return to Wales ten years later, where he died. The experiment was a failure. In Shepperson's account the first |

|

70 OHIO

HISTORY |

|

chapter covers Welsh backgrounds, the next three deal with conflicts over land titles in Tennessee, Roberts' associates, and his developmental and promotional projects (among them vineyards, sheep raising, mining, and railroads), the fifth with his work as a journalist, preacher, and political leader, and the sixth with the final years in Wales. A brief con- cluding chapter offers a balanced and perceptive summary of the reformer's career. The story contains far more about the Welsh in Ohio than about the Civil War in Tennessee, and the proportions are a wholesome reminder that the im- migrant's experience was often quite different from the oversimplified "in- terpretations" of the American past now widely current. Failure rather than suc- cess, repatriation instead of new founda- tions, and a thorny, uncompromising individualism rather than democratic blending, leveling, reconciliation, and co- operation are strikingly evident. The author, a graduate of Western Reserve University and long a student of British emigration to America, has searched a wealth of records in Wash- ington, London, Wales, Huntsville, Tennessee, and elsewhere and produced a narrative (not a biography) that is readable, impressively detailed, clear, and illuminating. Although it does not center on a major topic, it will be of much interest to all who are seriously concerned with Ohio and Tennessee history, the Civil War period, the Welsh, and the story of immigration. HARRY R. STEVENS Ohio University REMEMBER THE RAISIN! KENTUCKY AND KENTUCKIANS IN THE BATTLES AND MASSACRE AT FRENCHTOWN, MICHIGAN TERRITORY, IN THE WAR OF 1812. By G. Glenn Clift, with a prologue by E. Merton Coulter. (Frankfort: Kentucky Historical Society, 1961. xiii + 281p.; end-paper maps, appendix, bibliog- raphy, and index. $6.00.) On the eve of the sesquicentennial of |

|

the War of 1812, it is fitting that the Kentucky Historical Society has pub- lished this account of the role of Ken- tuckians in the prelude, battles, and massacre at Frenchtown on the River Raisin, the present site of Monroe, Michigan. Glenn Clift, assistant director of the society since 1950, has compiled an interesting, oft-times fascinating record of what was once optimistically styled the "Army of Canada" from its departure from Georgetown, Kentucky, on August 19, 1812, to its destruction in the snows of the Raisin Valley, January 18-23, 1813. Preceded by a lengthy prologue dealing with the causes of the war, the story of this ill-fated expedition has been skill- fully pieced together from such letters, diaries, and memoirs as have survived. From these accounts, valued insight is afforded for such figures of controversy as William Henry Harrison, James Win- chester, and Henry A. Proctor. Harrison emerges as a general who could do no wrong in the estimation of his men. In striking contrast, Winchester appears as a bungler bent on achieving success at Frenchtown in order to further his own advancement. How detested he was by some of his troops is evidenced by the following humorous excerpt from the diary of Private William B. Northcutt (p. 31): I always had some misgiveings about Winchester's Success with his Army, Knowing that he was not loved by his men, for they all despised him, and were continually playing some of their tricks of[f] on him. At one Encampment, they killed a porcupine and skined it and stretched the Skin over a pole that he used for a particular purpose in the night, and he went and sat down on it, and it like to have ruined him. At an- other Encampment they sawed his pole that he had for the same purpose nearly in two, so that when he went to use it in the night it broke intoo and let his Generalship, Uniform and all fall Back- wards in no very decent place, for I seen his Regimentals hanging high upon a |

|

BOOK REVIEWS 71 |

|

pole the next day taking the fresh air. Somehow it seemed almost fitting that Winchester's "Regimentals" would end up on the person of his captor, a drunken Indian known by the sobriquet of "Brandy Jack," who subsequently strut- ted about the battlefield at Frenchtown garbed in the general's cocked hat, coat, and epaulets. As for Henry Proctor, his culpability for the Indian massacre of the wounded prisoners left behind by his departing troops at Frenchtown on January 23, 1813, while not diminished by the evi- dence of his prior assurance of protection for these prisoners, is at least made un- derstandable in terms of his fear that Harrison's army was about to attack and that his return to the safety of Fort Maiden and Detroit would be hampered by the wounded Kentuckians in his custody. Genealogists will be pleased with the biographical sketches of the key figures of the campaign as well as with the troop rosters of the Kentucky companies in- volved in the debacle at la Riviere aux Raisins. PHILLIP R. SHRIVER Kent State University THE ST. LAWRENCE WATERWAY: A STUDY IN POLITICS AND DIPLOMACY. By Wil- liam R. Willoughby. (Madison: Uni- versity of Wisconsin Press, 1961. xiv + 381p.;

illustrations, bibliography, and index. $6.00.) This timely volume is concerned with the history of the improvement of navi- gation on the Great Lakes--St. Lawrence River system from the period of its earliest improvement to the end of the 1950's. Professor Willoughby devotes some sixty pages to the years before 1900, another seventy or so to the period from 1900 to 1930, and the balance (some 150 pages) to the years from 1930 to 1960. This obviously means that earlier developments have to be treated rather cursorily, but on the whole Pro- |

|

fessor Willoughby skillfully summarizes the early progress on the improvement of the waterway system. His greatest con- centration, however, is on the long strug- gles that finally led to the carrying out of the St. Lawrence Seaway project in the 1950's. As the subtitle of the work indicates, Professor Willoughby is concerned pri- marily with the political and diplomatic discussions and arguments on this con- troversial subject, and he deals with economic questions only in so far as they affect the political and diplomatic de- velopments. The author succeeds in pre- senting the many ramifications of the struggle with clarity. He successfully demonstrates how the obvious problem of the cost of improvement has been com- plicated at least since 1783 by national and sectional rivalry. A major problem was that the successful struggle for American independence meant that the Great Lakes--St. Lawrence system was artificially divided by the Canadian- American boundary. The uncertainty of British-American relations in the nine- teenth century considerably complicated the task of those who wished to establish an improved and unified water route to the sea. Even when British-American relations ceased to be a major obstacle, the task of agreement was complicated by American and Canadian nationalism, the Americans fearing dependence on a route that would pass through a foreign coun- try, and the Canadians fearing domina- tion by their powerful southern neighbor. Professor Willoughby shows the sensi- tivity of opinion in both Canada and the United States, and traces with care the tortuous and at times seemingly intermin- able negotiations that made the seaway possible. He also delves perceptively into the internal disagreements in both Canada and the United States, and shows how the difficulties posed in Canada by the prov- inces of Quebec and Ontario were matched in the United States by the |

|

72 OHIO HISTORY |

|

problems posed by the state of New York and by many special interest groups. Even the politicians who generally favored the seaway were limited by the difficulties of gauging popular support. Professor Willoughby's examination of the role of the various pressure groups has an in- terest that transcends the particular sub- ject with which he is concerned. In short, this is not a work hastily produced to take advantage of the current interest in the St. Lawrence Seaway. It is a carefully prepared and thoughtful book, and it deserves to reach a wide audience. REGINALD HORSMAN University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee TRIMMERS, TRUCKLERS, & TEMPORIZERS: NOTES OF MURAT HALSTEAD FROM THE POLITICAL CONVENTIONS OF 1856. Edited by William B. Hesseltine and Rex G. Fisher. (Madison: State Historical So- ciety of Wisconsin, 1961. xiv + 114p.; index. $3.50.) Historians long have profited from Murat Halstead's Caucuses of 1860, which Hesseltine and Fisher correctly describe as "a basic source book." Perhaps be- cause of preoccupation with Lincoln and the Wigwam intricacies, fewer scholars are familiar with Halstead's 1856 con- vention notes. By assembling the jour- nalist's earlier reports in this attractive little volume, the editors have performed a valuable service. Henceforth there will be less excuse for ignorance about maneuvers preceding James Buchanan's election. Whether written in '56 or in '60, Hal- stead's appraisals were partisan. The Ohio newspaperman made no secret of his allegiance to Republicanism or of his devotion to the antislavery cause. Over- simplifying complex issues as a propa- gandist to the manner born, he hoped for the nomination of candidates who would fight for fundamentals. In a sense, he was more disappointed by the Repub- licans' selection of John C. Fremont than by the Democrats' choice of Buchanan. |

|

Halstead thought that liberty would be served well if the people were given an opportunity to be disillusioned by "Old Buck." Halstead's characterizations suggest his lack of reverence for prominent politicians --or should we call it realism? Buchanan was an "experienced and veteran camp follower"; Millard Fillmore, "a mere consequent"; Franklin Pierce, "com- mander-in-chief of office holders"; Stephen A. Douglas, "a dishonest truck- ler" and "an ill-conditioned ape." Per- haps by coincidence, the Cincinnatian enjoyed identifying northwesterners with denizens of the animal kingdom. "Imagine a bull frog played upon by a steam whistle and you have" John Pettit of Indiana. As for Henry S. Lane, he was "a man about six feet high, marvelously lean, his front teeth out, his complexion between a sun blister and the yellow fever, and his small eyes glistening like those of a wild cat." The editors say that Halstead "made no pretense of objectivity" but had "a skepticism that bordered on objectivity." There are typically partisan tricks in his different attitudes toward Douglas before and after Buchanan's nomination, and in the altered reaction to John C. Breckin- ridge between June and September. Halstead made a fine contribution in covering the second Know Nothing con- vention. He missed the significance of John Slidell and Slidell's Democratic inti- mates in Cincinnati. Cynicism, color, controversy, humor, accurate and mis- leading predictions, "Colonel" Abraham Lincoln, and at least one prevarication are included in these reports. It is re- grettable that Halstead did not attend the Whigs' Baltimore convention in Septem- ber 1856. HOLMAN HAMILTON University of Kentucky FROM HUMBLE BEGINNINGS: WEST VIR- GINIA STATE FEDERATION OF LABOR, 1903-1957. By Evelyn L. K. Harris and |

|

BOOK REVIEWS 73 |

|

Frank J. Krebs. (Charleston: West Vir- ginia Labor History Publishing Fund Committee, 1961. xxv+553p.; illustra- tions, appendix, and index. $5.00.) Professors Harris and Krebs have pre- sented social scientists with a carefully written and well documented history of the West Virginia State Federation of La- bor from the date of its formation, with an uncertain future, in 1903 through 1957, when the organization stood as a symbol of the new AFL-CIO. From Hum- ble Beginnings supplies the kind of in- formation that will enable historians of the labor movement to give a better em- phasis to grass roots developments. Al- though this project was subsidized by the federation, the authors have been especi- ally fair in their treatment of moot ques- tions. The volume is admirably organized. The titles of the twelve chapters literally give the reader a synopsis. By way of illustration the first chapter is entitled "Organization and Dissolution, 1903- 1907." The title of the fifth chapter, "The Fight for Survival, 1905-1929," is equally suggestive. Many labor histories stress only to- getherness. The story of the West Vir- ginia Federation of Labor also demon- strates the presence of schisms, jealousies, internal rivalries, and the conflicting goals found in the world of labor. The federation was brought into exist- ence primarily through the efforts of old- time leaders. In fact, some of the spon- sors and founders had been members of, and were greatly influenced by, the de- funct Knights of Labor. On many occa- sions the federation was reduced to a skeleton membership. Certain craft un- ions, however, were determined to give the organization life. The entire story reveals the importance of experienced craft unions, such as the typographical and carpenters unions, in guiding the for- tunes of the federation. What were the accomplishments of the federation? Basically it cooperated with |

|

other groups in demanding social legisla- tion. It helped bring about a sound work- men's compensation act and woman's suffrage. It fought to strengthen the role of the West Virginia Labor Commis- sioner. There is, however, another ser- vice that has been so frequently over- looked. The federation aided in the organization of new unions, and it as- sisted small unions engaged in long strikes. In any history of labor in West Vir- ginia, obviously, the miners play an im- portant role. The relations between the craft unions and the industrial mining unions are discussed in some detail. From Humble Beginnings is not dra- matic. No one individual is singled out as the hero. In a sense the authors play the role of reporters--but very good re- porters. Professors Harris and Krebs have digested their materials and have told their story well and honestly. The illustrations have been chosen with some care. The great body of information relegated to the appendix should be help- ful to many specialists. The very com- plete index leaves the reader with a good taste. SIDNEY GLAZER Wayne State University OLD GENTLEMEN'S CONVENTION: THE WASHINGTON PEACE CONFERENCE OF 1861. By Robert Gray Gunderson. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1961. xiii+168p.; illustrations, appendix, bibliography, and index. $5.00.) The secession of the six cotton states by February 1, 1861, stemmed from fears that the election of the Republican Lin- coln on a platform opposing the extension of slavery would end the political domi- nation of the national government by the slave states and that the eventual extinc- tion of slavery impended. Lincoln, along with many in the North, believed that se- cession was a temporary crisis, and the general policy of northern moderates be- came one of retaining the border states in |

|

74 OHIO HISTORY |

|

the Union and providing additional time for the gulf states to reconsider their hasty action. Attempts at compromise were made to achieve this goal but were rejected by Republicans in the "lame duck" congress as yielding to slavery by permitting its extension into the terri- tories, a cardinal point demanded of con- ciliators by the South. Although the 1860 election results indicated that moderation was approved by the majority both north and south, "radicals" in one section and "fire-eaters" in the other managed to nullify all compromise endeavors and thus precipitated the Civil War. The Wash- ington Peace Conference, which met from February 4 through 27, 1861, was one such effort at conciliation. It was insti- gated by Virginia, one of the border states that stood to lose the most in a North-South struggle. This volume is a distinct contribution to the understanding of the purposes and achievements of this assembly, which de- rived its title from the age of the dele- gates. Most of them were the elder states- men of the nation, endeavoring to com- promise sectional differences once again. The author's theme is the necessity of these mediators to organize the nation's moderate majority into cohesive action to offset the activities of the more radical controlling minorities of both sections and thus avoid conflict. In an age that vener- ated and was influenced by elocution, the old gentlemen utilized their oratorical abilities in a sincere effort to alleviate the sectional strife. The extremists of the two sections, unwilling to yield, were not represented. Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan refused to arbitrate with "trai- tors," and the seceded states sent dele- gates to Montgomery instead, where, meeting on the same day as the Washing- ton Conference, the Confederate States of America was formed. But the delegates from the twenty-one states that responded to Virginia's call were successful in nego- tiating a settlement quite similar to the Crittenden proposals, which they sub- |

|

mitted to congress as a proposed thir- teenth amendment to the constitution. But the principal point, like Crittenden's, was the extension of the Missouri Compromise line. Congress was controlled by a Re- publican minority and, already having re- jected the Crittenden plan, refused to sub- mit the amendment to the states for con- sideration. The major contributions of the confer- ence were, as Professor Gunderson as- serts, its support of moderate forces in the February elections held in some of the border states on the question of se- cession, and its assistance in holding the border states in the Union until Lincoln was inaugurated. This latter point should have received more stress as it was the major objective of Seward's strategy dur- ing this period. Seward, Lincoln's spokes- man in congress, was bending all his efforts toward delay in secession in order to retain the border states and to make certain that Lincoln could be inaugurated peacefully. Lincoln and Seward believed that the seceded states would soon realize their folly and that the Union then could be reconstructed peacefully. But the pos- sibility that Seward initiated the peace conference as part of his plan of delay, as declared by Henry Adams, is categori- cally rejected by Professor Gunderson, and the fact that this convention contrib- uted much to Seward's success with his policy does not receive the emphasis it de- serves. And although the author rejects the "irrepressible conflict" doctrine, the book is studded with speeches and actions of the more radical spokesmen of both sides, leaving the impression that the con- ference was futile from the beginning. The title of the last chapter, "Better Now Than Later," is taken from a letter from Lincoln to William Kellogg in response to a request for Lincoln's views on com- promise. The president-elect is quoted as saying, "If the tug has to come, better now than later," but Lincoln was refer- ring to the extension of slavery and not to the inevitability of conflict as implied. |

|

BOOK REVIEWS 75 |

|

And Lincoln's words were more positive than the citation indicates, for he actu- ally declared, "The tug has to come & better now than later." But this short volume, including only one hundred pages of narrative, accur- ately recreates the political atmosphere of this turbulent period in a very read- able style. Using primary sources, the author manages to convey to the reader the tense situation that existed between Lincoln's election and his inauguration and the compelling need for compromise if belligerency was to be averted. Al- though it is questionable whether this topic can be treated adequately with such brevity, this is a book that will attract the general reader and add to the knowl- edge of the expert. R. ALTON LEE Central State College, Edmond, Oklahoma HISTORY OF SOUTH DAKOTA. By Herbert S. Schell. (Lincoln: University of Ne- braska Press, 1961. xiii + 424p.; maps, charts, supplementary reading list, and index. $5.50.) The history of a state is always in- teresting because it brings to light sig- nificant details which have not previously been easily available, and, if the work has been done by a competent scholar, it provides a valuable source of material for writers on the national level. The History of South Dakota is both interest- ing and scholarly. The author, Herbert S. Schell, dean of the graduate school and professor of American history in the State University of South Dakota, has been engaged in research on the history of his state for thirty years. Besides numerous articles, he has previously pub- lished three books about South Dakota. This book contains a comprehensive account of the development of the state to the present time. Chapter 1 deals with the natural setting and Chapter 2 with the Indians who inhabited Dakota. Then, beginning with the first appearance of |

|

French explorers in the region, the au- thor relates the history of South Dakota chronologically, except in the last four chapters, which are summaries of special subjects. Entitled in general "Reap- praisal," they deal respectively with the Sioux, the farm and ranch economy, manufacturing and mining, and social and cultural aspects of the state. After having made two constitutions, in 1883 and 1885, and without an ena- bling act of congress, South Dakota was admitted to the Union in 1889. As was the case in other territories, discontent with control from Washington spurred the people to demand self-government. Politically, the state has been Repub- lican except for brief periods. In 1912 the electoral vote was cast for Theodore Roosevelt, and in the following years a broad progressive program to promote social and economic welfare was carried out under the leadership of Governor Peter Norbeck. In dire straits as a result of the depression, the people in 1932 gave a majority to Franklin D. Roosevelt and elected Democrats to every state office. Although Roosevelt won again in 1936, Republicans regained control of the state government. In spite of attempts at industrialization, South Dakota is primarily agricultural, with farms east of the Missouri River and stock-raising ranches to the west. Flour milling and meat packing are the principal industries, and the production of metals and non-metallic materials is important in the state's economy. There are a number of maps and charts, and the end paper is a map of South Dakota. Unfortunately, so few towns are shown that the reader is often puzzled about the scenes of action in the text. A headpiece for each chapter is an attractive feature, and thirty-two pages of photographs are inserted in the center of the book. A section of "Supplementary Reading" and an index follow the text. F. CLEVER BALD University of Michigan |

NOTES

PICTURE OF A YOUNG

COPPERHEAD

1 Biographical notes on John W. Lowe by

Thomas O. Lowe, in Lowe Manuscripts Collection,

Dayton Public Library. All Lowe

manuscripts cited hereafter are in this collection. For an account

of John W. Lowe's life, see also the Xenia

Torchlight, September 18, 1861.

2 J. L. Rockey, History of Clermont

County, Ohio (Philadelphia, 1880), 137. Fishback had some

illustrious sons: George was an editor

of the St. Louis Democrat, and William was a law partner

of Benjamin Harrison in Indianapolis.

3 U. S. Grant to John W. Lowe, June 26,

1846. The original letter is not in the Lowe Collection,

but the copy in that collection,

according to the penciled notes of Thomas Lowe, was made from

the original in the possession of his

brother William. The copy is identical with the copy pub-

lished by Hamlin Garland in "Grant

in the Mexican War," McClure's Magazine, VIII (1897),

366-380. In his biography of Grant, Captain

Sam Grant (Boston, 1950), Lloyd Lewis calls attention

to the friendship between Lowe and Grant

while they were living in and around Batavia.

4 Letters to his father of November 20,

1853, and March 12, 1854, contain vivid accounts of

these debates.

5 Freeman Cary to John W. Lowe, June 23,

1853; Thomas O. Lowe to John W. Lowe, March

12, 1854.

6 Thomas O. Lowe to John W. Lowe,