Ohio History Journal

THE INTRODUCTION OF FARM MACHINERY INTO

OHIO

PRIOR TO 1865

by ROBERT LESLIE JONES

Professor of History, Marietta

College

Ohio agriculture in the fifth decade of

the twentieth century is

a highly mechanized industry, with

almost every farmer having a

heavy investment in devices ranging from

tractors to milking ma-

chines and pressure sprayers.

Contemporary mechanization, how-

ever, is less the product of recent

innovations than it is the culmina-

tion of a long development. When the

Civil War came to an end,

Ohio was one of the many regions in the

United States where farm-

ing already depended on labor-saving

machinery rather than on

the hoe and the sickle. Its achievements

were, it should be added,

not of long standing. The men who deeded

their homesteads to

their sons home from Shiloh,

Chancellorsville, and Chickamauga,

and thereupon retired to a country

village and a life of comparative

idleness alloyed with gardening, could

claim, not unreasonably,

that their generation had witnessed more

inventions and more

significant changes in agricultural

machinery than all preceding

ages combined.

To appreciate the importance of the

changes and innovations

in farming machinery in Ohio prior to

the end of the Civil War, it

is necessary to glance at pioneer

agriculture, with special reference

to the implements utilized therein.

The Ohio pioneer, like his

contemporaries east of the Alle-

ghenies and in the new West, bad few

implements for field labor,

and those he had were mostly clumsy and

primitive. As a rule they

were limited to a few hoes, a plow, a

harrow, a scythe, a sickle, a

rake or two, and a flail.

If the pioneer had a plow, it was either

a wood and iron one

(probably of the kind called a bull plow

or bar-share plow) or a

shovel plow. The bull plow, a legacy

from the late colonial era,

was mostly used to break up new ground,

and sometimes required

four or six oxen to draw it. It had a

beam six or seven feet long,

1

2

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

an iron standing coulter, a landside in

the form of an iron strap

or bar, a roughly forged iron point

resembling, so it was said, half

a lance head, and a mouldboard split

from a crooked tree. It was

seldom that such a mouldboard was curved

so as to lay a furrow

properly, and even if it was so curved,

it would scour only in the

most friable soils. Ordinarily,

therefore, a boy accompanied the

plowman to scrape the clay or clay loam

from it. Once he had the

ground broken, the pioneer might

continue with the bull plow, but

perhaps in most cases he relied on a

one-horse shovel plow. The

latter had become popular in the

seaboard colonies prior to the

Revolution, and was destined to remain

so in the South till after

the Civil War. It consisted merely of a

beam and a share re-

sembling a shovel with the convex side

forward. The shovel plow

worked better among roots than the bull

plow as it tended to be

stopped by them rather than to stretch

them and whip them back

on the operator's legs. It was,

moreover, considered indispensable

for the cross plowings which the fields

received once the sod was

broken, as well as for the cultivation

of the corn crop.1 Both the

bull plow and the shovel plow left the

land with an appearance

which might well be compared to that of

a modern field torn up

by a tractor-drawn disk plow. The field

that William Faux, the

English traveler, saw in Belmont County

in 1818 might have been

plowed with either type. He observed

that the "ploughing seems

shamefully performed, not half the land

is turned over or down-

wards. It seems (as we say at Somersham)

as though it was

ploughed with a ram's horn, or the snout

of a hog, hungry after

grubs and roots."2

Though the pioneer in many instances

lacked a plow, he

always had a harrow. This was because he

frequently found a

harrow much more useful to him,

especially on land recently

forest-covered. The harrow might be

constructed in any one of

several shapes inherited from the

colonial period, but when it was

to be used on newly cleared land, it was

invariably triangular to

1 For these plows, see Charles L. Flint

and others, Eighty Years' Progress of the

United States (2 vols., New York, 1861), I, 27, 30; Henry Howe, Historical

Collec-

tions of Ohio; Containing a Collection of the Most

Interesting Facts, Traditions,

Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes,

etc. (Cincinnati, 1849), 366; and

Martin Welker,

Farm Life in Central Ohio Sixty Years

Ago (Cleveland, 1895), 30. For a cut

of the

shovel plow, see Percy W. Bidwell and John I. Falconer,

History of Agriculture in the

Northern United States, 1620-1860 (Washington, 1925), 303.

2 W. Faux, Memorable Days in America:

Being a Journal of a Tour to the United

States (London,

1823), 167.

INTRODUCTION OF FARM MACHINERY 3

permit of its being drawn among stumps

and roots with a minimum

of interference. Though its chief

function was the pulverizing of

land already plowed, it served as a drag

for covering the seed

which had been broadcast, and

occasionally for scratching in seed

on land just out of the logging-fallow

stage.3

The implements already mentioned

sufficed not only for pre-

paring the ground for a crop of small

grains, but also for the

planting and cultivation of corn. Once

he had his land reasonably

clear of stumps, the pioneer farmer

struck out a series of furrows

three feet and a half apart, with a

second series of furrows similarly

spaced and at right angles to the first,

so that the intersections

would mark the points for the hills. The

children or the hired man

would drop the four or six kernels at

the intersections of the fur-

rows. If the droppers were fairly

skilful, only one set of furrows

was necessary, for they could advance

across the field in the direc-

tion of a peeled wand at the other side,

depositing the kernels as

they passed over the furrows. Planting

corn was so laborious that

many Ohio farmers made no attempt to

mark out hills, but simply

sowed the kernels, drill-fashion, in

shallow furrows.4 When the

corn came up, it was cultivated two or

three times with the shovel

plow, lengthwise and crosswise if in

hills, lengthwise only if in

drills. It was reckoned, at least in the

Scioto Valley, that a boy

and a horse would have no great

difficulty in keeping twenty-five

acres of corn well hilled up.5 Occasionally

a farmer would use

the harrow for the first cultivation,

especially if the field was

rough.6

The rest of his agricultural operations,

that is to say, the

3 James Flint, Letters from America,

Containing Observations on the Climate and

Agriculture of the Western States,

the Manners of the People, the Prospects of

Emigrants, &c., &c. (Edinburgh, 1822), 98-99. For cuts of various

harrows of the

early nineteenth century, see Ulysses P.

Hedrick, A History of Agriculture in the State

of New York (n.p., 1933), facing 292.

4 D. Griffiths, Two Years' Residence

in the New Settlements of Ohio, North

America: With Directions to Emigrants

(London, 1835), 62-63; Ohio

Cultivator

(Columbus), I (1845), 34; Patent Office

Report for 1851, Senate Executive Docu-

ments, 32 cong., 1 sess., No. 118, 375. The best and most

interesting account of corn

cultivation in Ohio during the pioneer

period is that of J. S. Leaming, which is re-

printed in W. A. Lloyd, J. I. Falconer,

and C. E. Thorne, The Agriculture of Ohio

(Wooster, 1918), 48-49.

5 Caleb Atwater, A History of the

State of Ohio, Natural and Civil (Cincinnati,

1838), 91; George H. Twiss, ed.,

"Journal of Cyrus P. Bradley," Ohio State Archaeo-

logical and Historical Quarterly, XV (1906), 233; letter from Zanesville in Maine

Farmer and Journal of the Useful Arts

(Hallowell, Me.), V (1837-38), 226.

6 Ohio State Board of

Agriculture, Annual Report for the Year 1849 (Columbus,

1850), 194-195. Hereafter this authority

is cited as Ohio Agricultural Report.

4 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

haying and harvesting, the pioneer

managed without the assistance

of horse-drawn implements.

During the early pioneer era the hay and

clover were cut

with a scythe. The grain was likewise

cut with a scythe, or, if the

ground was excessively rough or stumpy,

or the straw badly lodged,

with a sickle. However, by the time

grain-growing became an

established part of Ohio farming, the

scythe gave way in the wheat

field to the cradle.7 The

cradler would swing his way across the

field, laying the grain cut with each

sweep in a swath. He would

be followed by a binder, and the binder

by a raker to gather up

loose straws. Other hands then shocked

the grain. A good cradler

could cut four acres a day, but possibly

three would be nearer the

normal amount.8

A few farmers with large families had a

labor force which

was sufficient for harvesting, even if

they had to press the women-

folk into service as rakers, or, occasionally,

as binders.9 Farmers

with young families or large holdings

sometimes used help hired

solely for the harvest season. In

Champaign County, for example,

it was the practice to employ men from

the dairy farms of the

Western Reserve to work in the grain

fields.10 Inasmuch as it was

not always easy to obtain migratory

workers when they were needed,

nor to keep them when they were

obtained, the farmers sometimes

changed work, and had cradling bees. The

men, according to one

lyrical account, "would literally

march through the golden grain,

with a leader in front, enlivened by

song or joke, until the end of

the round was reached, where water, and

whisky and shade, would

rest the jolly reapers .... And woe to

the reaper who did not stand

the day's work and had to 'give out' and

lie in the fence corner,

and, in the parlance of the day, whose

'hide was hung on the

fence.' "11

When his fields became too wet or too

much frozen to permit

further working of them, the pioneer

commenced his threshing.

7 The cradle is said to have been

introduced into the seaboard states just after

the American Revolution. Lewis C. Gray

and Esther K. Thompson, History of Agri-

culture in the Southern United States

to 1860 (2 vols., Washington, 1933),

I, 170.

Its use was certainly well established

in Ohio long before 1830. Griffiths, Two Years'

Residence, 66.

8 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1859, 527. Cf. William T. Hutchinson, Cyrus

Hall McCormick: Seed-Time, 1809-1856 (New York and London, 1930), 71.

9 Ohio Cultivator, IX (1853), 200.

10 Ibid. III (1847), 107.

11 Welker, Farm Life in Central Ohio,

32-33.

INTRODUCTION OF FARM MACHINERY 5

Ordinarily he did it with the flail, as

was the prevailing method in

New England. Usually the place was the

hard-packed clay floor of

the barn. The best threshing time was on

a cold, dry winter day,

for if the weather was damp, the grain

did not beat out well. When

the beginner had learned how to swing

the "staff" (the longer stick)

so that the "supple" would not

hit him on head or shoulders, he

might gradually become proficient enough

to thresh out ten bushels

of wheat or twenty-five bushels of oats

a day. At this rate it might

well take a farmer most of the winter to

thresh out the product of

a ten-acre field. Accordingly, once he

found himself tilling a real

farm and not a mere clearance, he

usually hired laborers to thresh

for him. These laborers sometimes went

in gangs and did their

flailing in unison. About 1825 their

usual compensation was the

tenth bushel.12

When the farmer found that his crops

were too large to be

threshed with the flail, he quite

frequently did not hire batteries of

threshers, but used horses to tramp out

the grain. This was a

method which had been popular in

Pennsylvania and the states

adjacent thereto. Sheaves would be laid

out in a circle on the barn

floor, and the horses made to walk or

trot over them. It was esti-

mated that a team of horses could thus

thresh twenty-five bushels

of wheat a day. Sometimes four platoons

of horses would be used,

with a considerable force of laborers to

turn the sheaves over.

They could thresh about three hundred

bushels a day.l3

To clean the grain was as laborious as

to thresh it. Among

the small farmers the ancient practice

of winnowing prevailed. Two

men would whip a linen sheet backwards

and forwards to create

a little breeze, while the third slowly

poured the grain and chaff in

front of it. With the chaff out, the men

sifted the grain through a

coarse sieve or riddle often enough to

render it fit for use. Only

the really prosperous farmers had

fanning mills.14

As the pioneer era drew to a close in

Ohio, many new imple-

ments came into use. For the sake of

convenience these will be

divided in the paragraphs which follow

into three main groups.

12 Ibid., 31-32;

William C. Howells, Recollections of Life in Ohio, from 1813 to

1840 (Cincinnati, 1895), 154-156.

13 Lloyd, Falconer, and Thorne, Agriculture

of Ohio, 52; Frank E. Robbins, "'The

Personal Reminiscences of General

Chauncey Eggleston," Ohio State Archaeological

and Historical Quarterly, XLI (1932), 308.

14 Ibid.; Howells, Recollections of Life in Ohio, 62;

Welker, Farm Life in Central

Ohio, 31-32.

6 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL

AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

The first group will comprise those used

by wheat farmers in their

various operations, the second group

those used by corn growers

in so far as they differed from those of

the wheat growers, and the

third those used in hay making and

processing.

The new implement most widely adopted in

Ohio prior to mid-

century was the improved plow. The

beginning of the end of the

bull-plow era dates from 1819, when the

cast-iron plow was intro-

duced from New York. By 1827 local

demand for cast-iron plows

was great enough not only to support a

firm at Canton which em-

barked on the business of manufacturing

them, but to encourage it

to expand its production rapidly. By

1840 the production of this

and other foundries almost completely

displaced the bull plow in

Ohio.l5 The cast-iron plow in

turn gave way in some parts of the

state to the steel plow, which would

scour in prairie or bottom-land

soil. Though the first of these had

appeared in Illinois only in

1837, they gained a widespread

popularity elsewhere in the West

almost immediately. It was noted in 1850

that steel plows had

almost entirely superseded cast-iron

plows on the black soils of the

Miami Valley. The farmers who used them

found that they were

able to turn a furrow six or seven

inches deep, whereas earlier they

had never managed to average more than

four or five.16 By the

end of the Civil War, plows of the

general types now in use were

developed. Their mechanical improvement

contributed to a light-

ness of draft which was wholly lacking

in the older ones. This in

turn meant that plowing came to be done

with a two-horse team

(or a three-horse team if the soil was

heavy) rather than with oxen.

Steel plows retained their popularity on

the bottom lands, but the

ordinary farmer was satisfied that a

cast-iron plow was just as good

for any other kind of soil. On the

whole, therefore, steel plows

were much less frequently used in Ohio

than they were farther

west. Sulky plows were coming on the

market by 1865, but they

did not achieve much popularity in the

state till a somewhat later

period.17

A special kind of plow, the subsoil

plow, received frequent

15 Bidwell and Falconer, History of

Agriculture in the Northern United States,

210; The Ohio Guide (New York,

1940), 86, 182.

16 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1850 (Scott ed.), 399; Ohio

Agricultural Report

for 1851, 377; Ohio Cultivator, XV (1859), 50.

17 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1866, Part II, 135; Ohio

Agricultural Report for

1870, 432-433; Ohio Agricultural Report for 1873, 225.

INTRODUCTION OF FARM MACHINERY 7

and favorable notice in the agricultural

journals during the late

1840's and thereafter, but its

introduction was slow and experi-

mental. Subsoiling involved breaking up

the hardpan underneath

the six inches or so of soil moved by

the regular plow. The subsoil

plow had neither a landside nor a

mouldboard, being in fact really

only a point or tongue which could be

set to operate at a specified

depth. The best-known model was a

separate implement, drawn by

a team of horses following the standard

plow. There was, however,

another model with plenty of champions.

This was the "Michigan

Double-Plow," which was an

otherwise normal plow with a sharp

tongue attached to the bottom. The

Michigan Double-Plow was

used in Ohio beginning in 1852, and the

other kind beginning in

the late 1840's.18 Though it was

recognized that subsoiling was a

protection against both drought and

excessive wetness, and facili-

tated the extension of roots in the

growing crop, the practice was

as late as 1865 essentially something

for the farmers to speculate

about rather than to try for themselves.

At that time it was re-

stricted to vineyards, such as those in

Lorain County, and to very

cold, heavy clays, such as those of the

old beech forest of the

northeastern part of Stark County.19

In preparing the seedbed, most Ohio

farmers continued to rely

on harrows till after midcentury. These

were, however, increas-

ingly, and finally almost invariably,

"square" types. Some of them

were single, and the others hinged.20

The only rival of the harrow for the

purpose just mentioned

was the field cultivator, but whatever

threat it offered was more

potential than actual. A New York

patentee had wheel cultivators

of his own design, in essentials the

same as those of today, on the

market by 1846, and firms at Massillon

and Wooster were manu-

facturing similar models for use in

eastern Ohio wheat fields in

1848.21

The lack of reference to the adoption of

wheel cultivators

18 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1846, 41; Ohio Cultivator, II (1846), 57; Patent

Office Report for 1850, House

Executive Documents, 31 cong., 2 sess., No. 32, Part II,

6; Documents, Including Messages and

Other Communications Made to the General

Assembly of the State of Ohio (Columbus), XVII, Part II (1853), No. 5, 363. (Here-

after this authority is cited as Ohio

Legislative Documents.) For a cut of a subsoil plow,

see Ohio Agricultural Report for

1848, 168.

19 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1866, Part I. 173; ibid., Part II, 135.

20 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1848, 169. For cuts of the wooden-frame harrows

of the 1840's, see ibid., 170.

172.

21 Ohio Cultivator, II (1846), 172; Ohio Agricultural Report for

1848, 106, 178.

For a cut of the wheel cultivator, see

Bidwell and Falconer, History of Agriculture in

the Northern United States, 303.

8

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

throughout the 1850's would seem to

indicate that they did not

prove particularly necessary or

desirable to Ohio farmers. At the

end of the Civil War, however, it was

stated that in Summit County

the farmers frequently used them

"in preparing the soil for fall

grains, especially if it has been

fallowed."22

Field rollers, consisting of a

cylindrical section of a large

tree, were, according to one authority,

"in common use to crush

clods and compact the soil" in the

colonies before the Revolution.23

This statement seems highly

questionable, for, if they had been, it

is only reasonable to suppose that the

wheat farmers of Ohio would

have utilized them from an early period.

It is quite clear that very

few of them employed rollers. There were

many complaints in the

agricultural press to the effect that

rollers were seldom met with.24

One resident of Coshocton County

admitted in 1847 that he had

"never seen an implement of that

kind in this part of the country."25

During the 1850's Ohio farmers used

rollers more extensively than

earlier, but, even so, they were far

from adopting them universally

at the time the Civil War commenced.26

There was little improvement over the

old broadcast method of

seeding till almost midcentury. Seeders

were demonstrated at Co.

lumbus and Cincinnati in 1845, but they

seem to have been first

used in Ohio the next year, in Champaign

and Hamilton counties.

Gatling's drill, it was stated at the

end of 1848, had been in service

in the state for three or four seasons.

In 1849 over one hundred of

Palmer's seeders were sold and put into

operation in Ohio. Their

design, like that of most of their

competitors, was essentially the

same as that of the modern seeder.

Competition was so desperate

among manufacturers in 1850 that the

price fell from $80 or $100

to $40 or $50, and the use of seeders

was remarked in counties such

as Huron, Richland, and Tuscarawas.27

Farmers who expected that

their use of drills would both obviate

the danger of winter killing

22 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1867, Part II, 64.

23 Lyman Carrier, The Beginnings of

Agriculture in America (New York, 1923),

267.

24 Western

Farmer and Gardener (Cincinnati),

II (1840-41), 50; Ohio Agricul-

tural Report for 1846, 37; Ohio Agricultural Report for 1848, 172.

25 Ohio Cultivator, IV (1848), 9.

26 Ibid., XIII (1857),

9; Ohio Agricultural Report for 1861, lix.

27 Ohio

Cultivator, I (1845), 96, 156; ibid.,

II (1846), 27, 41; ibid., V (1849),

169, 297; ibid., VI

(1850), 291; Ohio Agricultural Report for 1848, 176;

Ohio Agricul-

tural Report for 1850 (Scott ed.) 273, 377-378; Patent Office Report for 1851. 375.

For cuts of Palmer's drill and Gatling's drill, respectively, see Ohio

Agricultural Report

for 1848, 175, 176.

INTRODUCTION OF FARM MACHINERY 9

and increase the yield by several

bushels an acre were disappointed

in the results; nevertheless, by 1861

drills were fairly common

throughout the wheat-growing sections of

Ohio.28 It was not till

about 1880, however, that grain drills

were used universally

throughout the state. Even then not

every farmer owned one, for

it was possible to rent one, subject to

the liability of not being able

to get it when it was most needed.29

Owing to the fact that cradling grain

was really an exhausting

task, and to the further and more

important fact that harvesting

operations were always a fight against

time, there came to be a

demand for mechanical devices to perform

the work. This was not

a development peculiar to Ohio, but one

found all over the United

States and in Great Britain as well.

However, one of the first

patentees of a reaper was Obed Hussey, a

mechanic who lived on

a farm near Cincinnati. He demonstrated

his reaper at the exhibi-

tion of the Hamilton County Agricultural

Society at Carthage in

July 1833. Though the machine broke down

several times, the

directors of the society were

sufficiently impressed by it to award

it a certificate of merit.30 The

Hussey reaper then became an

expatriate, for it was first

manufactured on a commercial basis at

Baltimore in 1837. There seems to be no

record of its reintroduc-

tion into Ohio prior to 1846, in which a

year a Hussey reaper was

mentioned as being in use in Champaign

County.3l In the mean-

time, that is to say, in 1845, the

machine of Hussey's great rival,

Cyrus Hall McCormick, made its

appearance in Ohio. It was tried

out in both Clark and Hamilton counties,

though not with much

satisfaction at first, because "no

person in attendance had ever seen

a machine of the kind before."32

During the next three or four

years, Hussey, McCormick, and other

models appeared in significant

numbers throughout all the wheat-growing

regions of the state. In

the spring of 1850 there were at one

time fifty or more reapers at

the steamboat landing in Sandusky,

imported from Chicago or

28 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1861,

lix.

29 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1879, 278; Ohio

Agricultural Report for 1882,

318.

30 Hutchinson, Cyrus Hall McCormick, 159-160.

31 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1846,

27. For cuts of the Hussey reaper, see

Bidwell and Falconer, History of Agriculture in the

Northern United States, 286, and

Ohio Agricultural Report for 1848, 181.

32 Ohio

Cultivator, I (1845), 108. For cuts of

the McCormick reaper, see Bid-

well and Falconer, History of

Agriculture in the Northern United States, 286, 289.

10

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Brockport, New York, for sale in Ohio.33

These imported reapers,

like those made locally, proved fairly

popular with the farmers in

spite of their high cost.34

These early reapers, whether McCormicks,

Husseys, or their

rivals, had many defects, though the

McCormick embodied all the

essential principles of the modern

reaper, including side-draft, the

vibrating horizontal cutter-bar, the

knife-guards, the reel, and the

raking platform.35 A general

criticism of the new reapers was that

they were hard to draw, sometimes

requiring three or four horses.36

A criticism of the McCormick

specifically, and seemingly a well-

founded one, was that it was excessively

flimsy in construction.37

John Klippart, perhaps the leading

midcentury authority on

Ohio agriculture and its development,

told of the reception accorded

the reaper-the McCormick in this

particular case-by the farm

laborers in north central Ohio.

"Every one of the 'harvest hands'

deliberately marched out of the field,

and told the proprietor that he

'might secure his crop as best he could;

that the threshing machine

had deprived them of regular winter work

twenty years ago, and

now the reaper would deprive them of the

pittance they otherwise

would earn during harvest.' "38

Their forebodings were to a con-

siderable degree unjustified; only the

cradlers were actually dis-

placed. The other harvest hands remained

in the original or in

slightly altered capacities. The Hussey

reaper, for example, re-

quired eight or nine men to attend

it-one to drive the horses at a

very fast walk, one to rake the grain

off the platform, five or six

to bind, and two to shock. The machine

could, with this gang, cut

an average of fifteen to twenty acres a

day.39

The use of reapers in Ohio received a

great impetus from the

trial which was held at Springfield in

1852. Nine reapers and three

combined reapers and mowers were in

competition. Perhaps two

thousand people were in attendance on

the opening day, "evidence

33 Ohio Cultivator, VI (1850), 217.

34 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1849,

88, 131; Ohio Agricultural Report for

1850 (Scott ed.), 76, 94. The cost of a McCormick reaper in

1849 was $115 cash,

and that of a Hussey in 1852

likewise $115. Hutchinson, Cyrus Hall McCormick,

317; Ohio Agricultural Report for

1852, 121.

35 Hutchinson, Cyrus Hall

McCormick, 52-53.

36 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1852,

121.

37 "A Farmer has need to remove all

the brash timber from a machine, substitut-

ing good oak, and adding iron braces

before he can venture to put it to good use."

Ohio Agricultural Report for 1853, 650. Cf. Ohio Agricultural Report for 1848, 182.

38 Ohio

Agricultural Report for 1859, 484.

39 Ohio Cultivator, II (1846), 121-122.

INTRODUCTION OF FARM MACHINERY 11

of the prevailing conviction that the

time has come when such work

must be done by other means than human

labor."40 At this time,

the gold rush to California and the

steady demand for construction

hands on the railroads then being built

in the Ohio and Mississippi

valleys made it very difficult to get

help. By 1855 the wages of

hired men in Ohio were twice as high as

thirty years earlier, though

still only about $200 a year. By the end

of 1857 there was such

an absolute scarcity of labor that

farmers had no alternative to

using more machinery.41

It was estimated in 1857 that there were

ten thousand reapers,

mowers, and combined reapers and mowers

in Ohio, of which all

but about three thousand had been

manufactured in the state.42

There were many different varieties,

each being supposed to have

some advantage over all the others, or

at least some of the others,

but in general the McCormick and those

made in imitation of it

were becoming the most popular.43 All

of them were much im-

proved over the old McCormick and Hussey

models. They were

simplified in construction, had means of

elevating the cutter-bar to

pass over stones or roots, and, most

important, had so much reduc-

tion in draft that a team of light

horses, at an average walk, could

do more than a team of heavy horses, at

a rapid walk or slow trot,

could have done a few years before.44

The reaper proved its real value when

the Civil War broke out.

"The mowing and reaping

machine," it was stated at the end of

1861, "has saved many harvests

which, owing to the demand for

men in other directions, could never

have been secured without

them. They are now in general use in

almost every township and

on almost every farm in Ohio."45 The harvest of

1862, it was

asserted, was "harvested with

machines, directed, in many cases, by

women and children."46 In 1863 a

firm at Canton manufactured

3,100 combined reapers and mowers, and,

in 1864, 6,000 of them.

40 Ibid., VIII

(1852), 209.

41 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1852, 302; Ohio Agricultural

Report for 1857,

43-44; Ohio Agricultural Report for

1859, 485.

42 Cleveland had manufactured 1,643,

Sandusky 1,000, Springfield 1,300, Dayton

1,826, and Canton 1,507. Ohio Agricultural

Report for 1857, 42.

43 For nine

pages of cuts and descriptions of the leading reapers of Ohio, as

shown at an exhibition at Hamilton in 1857, see ibid.,

95-103.

44 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1858,

141; Ohio Agricultural Report for

1861,

Ivii.

45 Ibid.

46 Ohio Agricultural

Report for 1867, Part I, x.

12

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

In 1864 two firms at Dayton together

manufactured 4,036.47 Thou-

sands in addition were imported from

outside the state. By the end

of the war the slow and laborious

process of harvesting with cradles

had given way almost everywhere to the

reaper.48

Threshing machines first came into use

in Ohio in the late

1820's. There were ten in operation in

Hamilton County in 1828.49

In 1831 they appeared in northern Ohio,

where they encountered

much vocal opposition from the laborers

who had theretofore earned

their winter livelihood by the flail,

but no actual violence.50 After

this time, the great demand for wheat

assured their use in ever in-

creasing numbers. A letter from

Zanesville in 1837 stated that

"the use of threshing machines is

getting quite common here."51

These early machines, like those in

service elsewhere in the

country, were of every variety, as they

were manufactured locally

by the village mechanics as well as

being imported. They operated

usually on the beating principle, in a

sense like a battery of me-

chanical flails. Because they lacked any

means of separating the

grain from the chaff, they were

exceedingly dirty in operation. They

were driven by horsepowers, either of

the revolving or the tread-

mill type. By about 1845 these primitive

machines were giving

way to improved ones, usually

manufactured either according to

Pitt's patent of 1837 or in imitation of

it. These new threshers were

portable, threshed by means of a

revolving cylinder, had a built-in

separating and fanning arrangement, and

had a bagger. Such ma-

chines were said to be in fairly general

use in Champaign County

in 1846, and doubtless this was true of

the rest of the state as well.

At any rate, by 1850 very little wheat was

being trodden out by

horses anywhere in Ohio.52 At

the end of the 1840's, the common

machines required ten to twelve men and

six horses to operate them,

but they could thresh from two hundred

to four hundred bushels of

wheat a day. As the labor force was

large, and the machines far

from cheap, farmers sometimes united in

ownership of one, but

47 Agriculture of the United States in 1860; Compiled from

the Original Returns

of the Eighth Census (Washington, 1864), xxii.

48 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1866,

Part I, 173.

49 Eugene H. Roseboom and Francis P.

Weisenburger, A History of Ohio (New

York, 1934), 179.

50 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1859, 484.

51 Maine Farmer, V (1837-38), 226.

52 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1846,

27; Ohio Agricultural Report for 1849,

180, 214; Ohio Agricultural Report

for 1850 (Scott ed.), 399; Ohio Agricultural Report

for 1862, lviii. For cuts of early threshers, see Bidwell and Falconer, History

of Agri-

culture in the Northern United

States, 215, 298.

INTRODUCTION OF FARM MACHINERY 13

ordinarily, for the same reasons, they

depended on the itinerant

combinations of horsepower and thresher.53

By the end of the 1850's, threshers had

undergone still further

modifications. They usually had a

conveyor to carry the straw

from the machine to the stack, an

endless belt which British and

Continental observers considered a great

novelty.54 The greatest

defect of the threshers was that they

still cleaned very imperfectly,

and so left a vast amount of smut and

weed seeds in the grain.

This condition was ascribed largely to

the fact that the grain deal-

ers failed to discriminate in price

between clean and dirty samples,

so that it was not worth while for the

farmer to insist on cleaner

threshers.55

Steam engines came into use for

threshing in Ohio during the

middle 1850's. An itinerant thresher

employed the first of them in

the vicinity of Chillicothe during the

season of 1855. This engine

and its successors proved very popular,

not so much because they

saved money as because they saved time,

and so made it possible

to get the crop to market before prices

fell. There were upwards of

fifty steam threshers in operation in

Ohio in 1859, with the result

that in a few sections the old

horsepowers were completely super-

seded. In 1862-63 a single Ohio firm

manufactured over two hun-

dred portable steam engines for use with

threshing outfits. During

and after the Civil War more and more

engines were sold, so that by

1876 only sixteen counties reported that

threshing was still done by

horsepowers.56

The new machines used in connection with

the corn crop were,

in their own way, perhaps even more

important than most of those

developed in connection with small

grains.

The first corn planters appeared as

early as 1841, for they were

being manufactured at Cincinnati in that

year. Till about 1850,

53 Ohio Cultivator, III (1847), 49; Ohio

Agricultural Report for 1848, 183;

Cultivator (Albany), n.s., VII (1850), 308.

54 Agriculture of the United States

in 1860, xxiii; Journal of the

Royal Agricul-

tural Society of England, quoted in Ohio Agricultural Report for 1859, 526.

For a

cut of a Pitt thresher, manufactured at

Dayton in 1865, see Ohio Agricultural Report

for 1865, Part II, 147.

55 Department of Agriculture Report for

1862, House Executive Documents, 37

cong., 3 sess., No. 78, p. 94.

56 Ohio Cultivator, XI

(1855), 340; Ohio Agricultural Report for 1857, 43;

Ohio Agricultural Report for 1859, 535; Ohio Agricultural Report for 1862, lvi;

Ohio

Agricultural Report for 1876, 624-626. For a cut of a portable steam engine manu-

factured at Newark in 1857, see Ohio

Agricultural Report for 1857, 147; for a cut of

another portable engine, this one

manufactured at Richmond, Indiana, in 1865, and

probably used to a considerable extent in the nearby

parts of Ohio, see Ohio Agri-

cultural Report for 1865, Part

II, 137.

14

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

however, they were of little value as

they were complicated and

easily clogged. As late as 1852

"Barnhill's Corn Planter," manu-

factured by a machine shop at

Circleville, which, the Ohio Culti-

vator stated, "had a great run the present

season," sold only to the

extent of 400 units. The popularity of

the corn planter would

nevertheless seem to date from about

this time. Many planters

were introduced into Madison County in

1853, much to the ad-

vantage of the farmers, who found that

they made it possible for

one man to perform the work of six in

the old way. A few farm-

ers were using horse-drawn corn planters

by the end of the Civil

War, but these were all men with large

and level fields. Individuals

on small or rough farms considered

them more expensive than

advantageous.57

About 1840 the old method of cultivating

corn with the shovel

plow came to be replaced by one using

horse-hoes or "culti-

vators."58 These were

hybrid creations, combining some of the

features of the plow and the harrow.

They had the frame of a

harrow with plow handles attached, and,

instead of the conventional

spikes of the harrow, teeth of various

designs, sometimes miniature

plow shares, sometimes small shovels,

sometimes curved teeth. As

time passed they came to be adjustable

for width. Models of one

kind or another were quite common in

Ohio by 1848.59 It was

stated in 1854 that "the [Western]

Reserve farmers are discarding

the miserable practice of plowing out

and hilling up corn, and we

observed everywhere the fields were

dressed out clean and level,

with the cultivator."60 As by this

time the cultivator was being em-

ployed by even the farmers in such newly

settled counties as Erie

and Huron,61 it is safe to

assume that its use was well-nigh universal

throughout the state. During the early

1850's and afterwards, some

farmers used both the cultivator and the

double-shovel plow,62 the

57 Charles Cist, Cincinnati in 1841:

Its Early Annals and Future Prospects (Cin-

cinnati, 1841), advertisement; Ohio

Cultivator, VIII (1852), 169, 185; Ohio Agricul-

tural Report for 1853, 604; Ohio Agricultural Report for 1867, Part II,

3-4. For cuts

of corn planters similar to those used

in Ohio, see Bidwell and Falconer, History of

Agriculture in the Northern United

States, 300-301.

58 There would seem to have been few, if

any, cultivators in Ohio prior to 1840.

A Down Easter resident at Zanesville

stated in 1837 that "I have not seen the culti-

vator this side of Rochester, N.

Y." Maine Farmer, V (1837-38), 226.

59 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1848,

178. For a cut, see Bidwell and Falconer,

History of Agriculture in the

Northern United States, 302.

60 Ohio Cultivator, XII (1854), 201.

61 Ohio Legislative Documents, XVIII, Part II, 1854, No. 21, p.

581.

62 For a cut of the double-shovel plow,

see Bidwell and Falconer, History of

Agriculture in the Northern United

States, 304.

INTRODUCTION OF FARM

MACHINERY 15

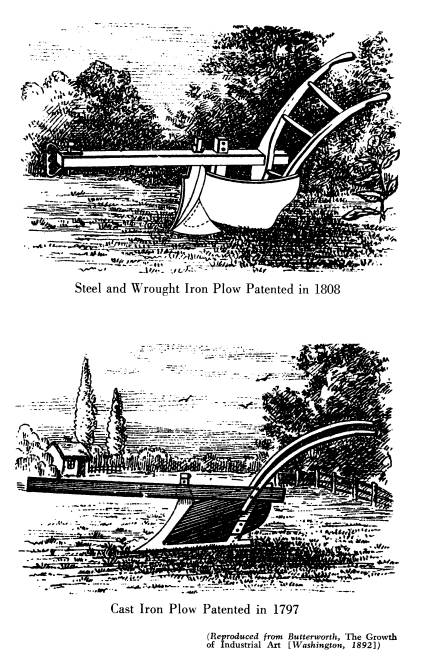

Click to view plows patented in 1808 and 1797.

former till the corn was well shot up above

the ground, the latter

thereafter. They found the results so

satisfactory that few of them

went back to the single-shovel plow.

These few did so only because

they believed they could thereby

"hill up" the rows better than with

the double-shovel plow, and so enable

the corn stalks better to with-

stand windstorms.63

During the pioneer era and afterwards,

the corn to be used in

the form of grain was threshed out of

the ear either by means of the

flail or by treading out with oxen.64

There were many other effective,

if tedious methods, such as rubbing two

ears together to make them

shell each other, or scraping an ear

across the blade of a shovel.

Owing to the slowness of such methods,

there came to be a demand

for corn shellers. These were of many

designs, but possibly the

commonest was a cylinder covered with

teeth and turned by a crank.

Such machines were being offered for

sale at Cincinnati in 1841.65

Five years later an Ohio agricultural

editor simply noted that the

"common hand corn sheller" was

"constructed in various forms,

but the principle of all is much the

same, and too well known to

need description."66 They

sold for from $14 to $18, and enabled

a man to shell about forty bushels a

day.67 Partly owing to the

great emphasis placed on the "corn

and cob mills" at the state fair

of 1855, they were thereafter in steady

demand. "Even the Hard-

ware, and the Commission

Merchants," it was stated at the end of

the year, "would as soon be without

nails or salt, as without 'Corn

and Cob Mills.' The question of utility,

in the use of these mills,

has been pretty well settled, by

producing ample proof that two

bushels of ground corn, are fully equal

to three bushels in the

ear."68

While the farmer was acquiring special

implements for deal-

ing with his small-grain and corn crops,

he was going through the

same process in connection with the

cutting, storing, and marketing

of his hay.

Till the late 1840's, hay on the old

cleared farms everywhere

63 Patent Office Report

for 1853, Senate Executive Documents, 33 cong., 1 sess.,

No. 27, p. 118; Ohio Agricultural

Report for 1861, lxiii; Ohio Agricultural Report for

1867, Part II, 4.

64 Griffiths, Two Years' Residence, 64.

65 Cist, Cincinnati in 1841, advertisement.

66 Ohio Cultivator. II (1846), 181.

67 Ibid., III (1847), 37; Department of Agriculture Yearbook for

1899, House

Documents, 56 cong., 1 sess., No. 588, pp. 317-318.

68 Ohio Agricultural Report for

1855, 61.

16 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

in Ohio was still being cut with the

scythe. After this time it was

more and more cut with reapers or

mowers. Specialized mowers

appeared in Ohio in the late 1840's,

though in very small numbers,

for they had to compete with the

reapers, which could be converted

into mowers by removing the platform and

lowering the cutter-

bar. The first mower proper in Ohio of

which there is record was

a Ketchum model which appeared in

Champaign County in 1848.69

However, at the trial of reapers and

mowers held at Springfield,

Ohio, in 1852, the judges considered

that Ketchum's mower was

superior in its performance to either

the McCormick or Hussey

reapers used as mowers.70 Five

years later, at a trial held at Ham-

ilton, Ohio, the judges had nothing but

commendation for a new

type of mower, known as the

"Ohio," which was manufactured by

Bell, Aultman, & Co., a Canton

implement factory. This machine,

like others then beginning to come into

use elsewhere in the country,

had a hinged cutter-bar and two drive

wheels, the latter acting

independently so that the mower could

cut otherwise than in a

straight line.71 The two-wheel mowers

were shortly recognized

almost universally as better than the

combined reapers and mowers,

or than the one-wheel mowers, but many

of both the latter types

continued to be sold down to the

outbreak of the Civil War.

The pioneer, if he wished to expedite

the curing of the hay, or

to prevent it from molding in the swath,

had no alternative to

turning it over with a pitchfork. The

modern farmer has at his

disposal a side-delivery rake or a

tedder, either of which literally

kicks the hay over so that it can dry in

the sun and air. The side-

delivery rake was a development of the

1890's, however, and such

tedders as there were in Ohio during the

third quarter of the

century were really curiosities. As late

as 1876 it could be stated

that there were very few of them in the

state.72 Here, then, there

was scarcely any advance over the

pioneer era.

Raking hay by hand was tedious, so that

among the first im-

provements in hay-making technique was

the introduction of the

69Ohio Cultivator, IV (1848), 68. Down to the middle 1850's, Ketchum's

mower and its inferior rivals all had a

single drive wheel. For a cut of the Ketchum

mower, see Bidwell and Falconer, History

of Agriculture in the Northern United

States, 294.

70 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1852, 122-123.

71 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1857,

93-94 with a cut. For a cut of the

Wood

mower, a very similar type, see Bidwell and Falconer, History

of Agriculture in the

Northern United States, 295.

72Ohio Agricultural Report for 1876, 626.

INTRODUCTION OF FARM MACHINERY 17

horse rake. The first of these new rakes

was simply a large comb,

ten feet wide, and with teeth twenty

inches long, which had handles

attached to it to guide it over stumps

and stones. It came into use

in Pennsylvania about 1820, and

doubtless about the same time or

shortly thereafter in Ohio. A useful

modification was the revolving

rake, resembling a large double-comb,

which could be dumped

without stopping the horse. This was

introduced into southeastern

Ohio-Washington County, specifically-as

early as 1835. In 1848

it was in common use in many other parts

of Ohio, but it was still

rare in other sections of the state.73

The spring-tooth horse rake

made its appearance in Ohio in 1847,

having been introduced from

New York. Perhaps the most common type

was constructed more

or less in imitation of that of Delano,

a Maine patentee. It was

mounted on a set of wheels, such as

those of an ordinary farm

wagon, and the hay was emptied by the

pressing of the operator's

foot on a treadle. The teeth were

operated independently of one

another, so that they adjusted

themselves to the inequalities of the

ground. Delano-model horse rakes were

imported into Ohio at

first, but in 1852 they began to be

manufactured locally.74 At the

end of the 1850's, horse rakes of this

and other kinds were in

general use in all but half a dozen

counties. By the outbreak of

the Civil War, there were few farmers in

the grass-growing parts

of the state who still raked hay by

hand.75

It was not till midcentury that

mechanical invention did much

to lighten the drudgery of drawing in

hay. The amount of labor

theretofore required of course varied

from one part of the state

to another and from farm to farm,

depending on the storage space

available and on the kind of agriculture

practiced. When the hay

was to go into a stack, some farmers

simply transported it thither

by roping it, that is, by dragging the

cock along with a rope or

a wild grapevine. This was a common

practice in central Ohio,

but it seems that it was completely

unknown in some other parts of

the state where wagons were used

instead, as they were for drawing

73 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1848, 182; Marietta Tri-Weekly

Register, January

19, 1893; Bidwell and Falconer, History

of Agriculture in the Northern United States,

213. For cuts, see ibid., 213-214.

74 Ohio Cultivator, III (1847), 25;

ibid., VII (1851), 364; ibid., X (1854),

178. For a cut of Delano's rake, see

Bidwell and Falconer, History of Agriculture in

the Northern United States, 297.

75 Ohio Agricultural Report for 1857,

510-511; Ohio Agricultural Report for

1861, xlviii.

18

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

in sheaves.76 When the farmer

stored his hay in the barn, as was

commonly done on small farms such as

those of the Western

Reserve, he sometimes had two or three

men to mow it back, one

pitching it on to the next. To economize

labor, a few farmers

began about 1850 to utilize a horse fork

for unloading hay either

through the gable end of the barn or, by

means of a temporary

frame, at a stack. The fork was at first

a rather awkward contriv-

ance. It had four prongs and a handle,

with the point of suspen-

sion at their junction. A rope on the

end of the handle gave the

operator the opportunity to balance the

load as it ascended on the

prongs. When the load was sufficiently

elevated, he released the

rope, and the hay slid off the prongs.

One such fork, as first used

in Stark County in 1850, was imitated

from a model found in

Pennsylvania at a somewhat earlier

period and cost about $7.00.

By 1860 Ohio had its fair share of the

tens of thousands of later

models of this and similar forks then in

use in the United States.77

Though hay was an important crop

throughout Ohio, and

especially so in the dairying counties

of the Western Reserve, it

had only nearby markets till well on

towards midcentury. Before

it could be sold at any distance, its

bulk had to be reduced by

baling. The first balers were

"cotton and hay presses," of a type

advertised by a Cincinnati foundry in

1841.78 The models in use

along the Ohio River were probably in

general like the one bought

by a southern Indiana farmer in 1845. It

had an iron screw, and

a device called the beater to shove in

the hay as the screw was

being withdrawn, and produced bales four

feet by two feet by two

feet, weighing about 250 pounds. Three

men and a boy (to drive

the horse) could, with this "Mormon

Press," bale about five short

tons a day. The press cost about $175,

and the building to house

it $100 more.79 In certain

areas, such presses made it profitable to

sell hay for export. By 1852

"hundreds of tons" of baled timothy

and red top were being shipped annually

from the one station of

Westborough in Clinton County.80 The

trade grew in importance

76 Welker, Farm

Life in Central Ohio, 32; Ohio Agricultural Report for 1861,

lviii.

77 Ibid.; Ohio Cultivator, VI (1850), 209; Agriculture of

the United States in

1860, xxiii; Ohio

Agricultural Report for 1861, lviii. For a cut of a fork

manufactured

at Upper Sandusky, see Ohio

Agricultural Report for 1865, Part II, 151.

78 Cist, Cincinnati in 1841, advertisement.

79 Patent Office Report for 1850, 223.

80 Patent Office Report for 1852, Part II, Senate Executive

Documents, 32 cong.,

2 sess., No. 55, p. 259.

INTRODUCTION OF FARM MACHINERY 19

along the Ohio during the 1850's on

account of the demands of the

riverine cities and the South, and

during the early 1860's on ac-

count of army needs. Before the end of

the war the cost of baling

was reduced to less than a dollar a ton.

The balers were ordinarily

set up at the depots, where they were

operated on a custom basis

or by hay buyers, and were still of the

screw type.81

The only other machines used in

connection with hay or clover

prior to the end of the Civil War were

for threshing and cleaning

cloverseed. Originally, clover was

threshed with a flail, but about

1840 clover hullers or

"concaves" made their appearance in Ohio,

and thereafter were frequently

mentioned.82 These hullers did not

thresh the seed out, but merely cleaned

the hulls from the seed

after the heads had been trampled out by

oxen. A man and two

horses could clean a maximum of about

ten bushels a day with one

of them. By the time of the Civil War

the hullers were being re-

placed in Ohio, as elsewhere in the

Union, by machines which

threshed and cleaned in the one

operation, and which in general

resembled the threshing machines of the

day.83

Local patriotism in Ohio has tended to

emphasize the im-

portance and uniqueness of agricultural

improvements within the

state. It would seem, however, that in

respect to the introduction

of labor-saving machinery at least, Ohio

farmers did not stand in

the forefront of innovators, but rather

followed the dictum of

Alexander Pope, "Be not the first

by whom the new are tried, nor

yet the last to lay the old aside."

Many of their new implements

were imported from New York or even New

England, and those

which were manufactured locally were

frank imitations of out-of-

state prototypes. Factories advertised

that their reapers were made

on Manny's model and their mowers on

Ketchum's, and farmers

who traveled beyond the limits of the

state came home resolved to

construct for themselves some one or

other of the simpler machines

81 M. L. Dunlap, "Agricultural Machinery,"

Commissioner of Agriculture Report

for 1863, House Executive Documents, 38

cong., 1 sess., No. 91, p. 430. Dunlap

was a resident of Illinois, but

he wrote from the point of view of the Middle

West in

general. For a cut of "Colohan's portable hay

press," a model manufactured at Cleve-

land, see Ohio Agricultural Report

for 1863, 68. The continuous baler was not

patented till 1866.

82 Cist, Cincinnati in

1841, advertisement, Ohio Agricultural Report for 1847,

88; Ohio Agricultural Report for

1848, 106; Ohio Agricultural Report for 1849, 48.

For a description, see Robert Leslie Jones,

"Special Crops in Ohio to 1850," Ohio

State Archaeological and Historical

Quarterly, LIV (1945), 132.

83 Dunlap, loc. cit., 433-434.

20 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

they observed

when away.84 Neither were Ohio farmers of the

period under

consideration notable among their contemporaries for

the rapidity

of their mechanization. The returns of the Seventh

Census

(1850), the Eighth Census (1860), and the Ninth Census

(1870) show

that they lagged behind the farmers of New York

and

Pennsylvania, though they did keep almost exactly abreast of

those of

Indiana and Illinois.85 In short, as far as the introduction

of

agricultural machinery prior to the end of the Civil War is con-

cerned,

Ohio's significance consists not in the state's being excep-

tional, but

in its being typical of the Middle West.

84 For

example, a Washington County farmer visited Connecticut in 1856 and

took the

measurements of a spring-tooth dump rake he saw there. He came home, and

by

constructing a wooden frame himself, and having the blacksmith help with the

iron parts,

pioneered the introduction of this type of machine in his community.

Marietta

Tri-Weekly Register, January 19, 1893.

85 Estimated

approximate value of farming implements and machinery per

hundred acres of improved

land:

| 1850 | 1860 | 1870 |

|

| Illinois............................................ | $127 |

$132

|

$178 |

| Indiana.......................................... | $132 | $127 | $175 |

| New York..................................... | $178 | $203 | $295 |

| Ohio.............................................. | $128 | $139 | $177 |

| Pennsylvania............................... | $171 | $214 | $309 |

Computed

from statistics in The Statistics of the Wealth and Industry of the

United

States; Compiled from the Original Returns of the Ninth Census (Washington,

1872), 81,

86, 90.