Ohio History Journal

DOUGLAS V. SHAW

Interurbans in the Automobile Age:

The Case of the Toledo, Port Clinton

and Lakeside

From the first decade of the twentieth

century until the early 1930s electric

interurban railways connected almost all

Ohio towns and villages of more

than 5000 population. With its numerous

cities and market towns within

reasonable proximity of one another,

prosperous agriculture, and generally fa-

vorable topography everywhere but in the

southeast, Ohio provided ideal terri-

tory for interurban development.

Promoted vigorously from 1890 until 1910,

interurbans quickly became important

components of regional transport sys-

tems; at the industry's height between

1914 and 1918 the Ohio system

reached its maximum of roughly 2800

miles.1

Built and operated in many respects like

urban street railways, interurbans

offered greater frequency of passenger

service and more rapid delivery of local

freight than did steam railroads. Most

offered service at no less than two-hour

intervals, headways far shorter than

those maintained on typical local railroad

lines. Increased convenience and

flexibility formed the core of interurban suc-

cess, and electric lines tended to

replace steam roads as the transport mode of

choice between points where the two competed

directly for traffic.2 Yet in the

long run the industry was not a success.

Most interurbans never developed

Douglas V. Shaw is Associate Professor

of Urban Studies in the Department of Urban

Studies, The University of Akron.

1. George W. Hilton and John F. Due, The

Electric Interurban Railways in America, second

printing (Stanford, 1964), 4-25; Report

of the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio for the Year

1917 (Springfield, Ohio,

1918), 645 (hereafter abbreviated as PUCO Report, [year]); George

S. Davis, "The Interurban Electric

Railways of Ohio," Street Railway Journal, 18 (August 3,

1901), 145-56. See also "The Latest

Ohio Interurban Map," Street Railway Review, 12 (March

20, 1904), 190-91.

2. Hilton and Due, 14-15; Guy Morrison

Walker, "The Why and How of Interurban

Railways," Street Railway Review, 14

(June 20, 1904), 365-68; Ernest L. Bogart, "Economic

and Social Effects of the Interurban

Electric Railway in Ohio," Journal

of Political Economy,

14 (December, 1906), 588-92. Within four

years of the opening of the Interurban Railway and

Terminal Company between Cincinnati and

Lebanon in 1902, for example, passenger traffic

on the Cincinnati, Lebanon and Northern

steam railroad fell 59 percent. John W. Hauck,

Narrow Gauge in Ohio: The Cincinnati,

Lebanon and Northern Railway (Boulder,

1986), 226-

27. On the development of freight

traffic, see Charles S. Pease, Freight Transportation on

Trolley Lines (New York, 1909).

126 OHIO

HISTORY

sufficient traffic and revenue levels to

assure financial stability and few in-

terurbans ever paid consistent returns

on their investment for very long. After

1925 lines were abandoned as rapidly as

they had been built before 1910, un-

able to meet their fixed charges as

traffic dwindled in the face of competition

from automobiles, buses, and trucks.

Indeed, toward the end many lines pro-

duced more net revenue from the sale of

electricity to communities and farms

along their rights-of-way than from the

sale of transportation itself.3

The Toledo, Port Clinton & Lakeside

provides an excellent illustration of

the aspirations, insurmountable

difficulties and dashed hopes of the interurban

industry. Completed in 1906 between

Toledo and the end of the Marblehead

peninsula to the east, the road lost

money during every year of its existence

when all proper charges are computed.

Yet the line did not discontinue pas-

senger service until 1939, one of the

last in the state to do so. Owned for all

but its first seven years by utility

holding companies willing to underwrite its

losses, the Toledo, Port Clinton &

Lakeside avoided the bankruptcy and aban-

donment which would have been its

certain fate had it continued as an inde-

pendent corporate entity. Because it

survived so long its records allow explo-

ration of the manner in which this

interurban and others interacted with the

development of automotive transport and

with increased demand for electricity

in its service area.4

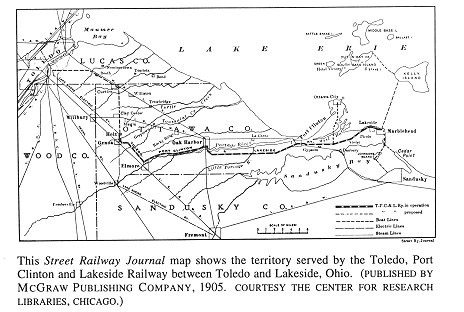

The Early Years, 1902-1912

The Toledo, Port Clinton & Lakeside

was incorporated in late 1902 by a

group of wealthy and well-connected

Toledo businessmen. By linking the

Marblehead peninsula in Ottawa County

with Toledo they expected to secure

much of the heavy seasonal tourist

traffic to peninsula and island resorts and

to the large Methodist camp at Lakeside.

They also expected the area's lime-

stone and gypsum mines and highly

productive farms and fruit orchards to

supply a respectable freight traffic.

Securing franchises to lay track on village

streets in Genoa, Oak Harbor, Port

Clinton and Marblehead in the spring and

summer of 1903, the company prepared to

build.5

3. Hilton and Due, 54, 208-51;

"Selling Energy Along Interurban Railways," Electric

Railway Journal, 48 (October 28, 1916), 920-25.

4. The records of the Toledo, Port

Clinton & Lakeside and successor companies are part of

the Ohio Edison collection, housed in

the American History Research Center, University of

Akron Archives, University of Akron,

Akron, Ohio. See also George Hilton's excellent The

Toledo, Port Clinton and Lakeside

Railway, Bulletin No. 42, Electric

Railway Historical Society

(Chicago, 1964).

5. Hilton, 3-4; "Toledo, Port

Clinton and Lakeside," Street Railway Journal 26 (December

30, 1905), 1130-32; "Annual Report

of the Toledo, Port Clinton and Lakeside Railway to the

Railroad Commission of Ohio for the Year

Ending June 30, 1908" (hereafter abbreviated

"TPC&LS Railroad Commission

Report," 1907-08), 16, 18, Box 157, Ohio Edison papers

|

Interurbans in the Automobile Age 127 |

|

Like other interurban promoters, the men behind the TPC&LS constructed the line through their own closely held Toledo Interurban Construction Company. Issuing $1,500,000 in five percent first-mortgage bonds and $1,800,000 in common stock, they turned these securities over to the con- struction company which in turn sold the bonds and some of the stock to raise the money necessary to cover construction costs. The first segment, from Genoa to Port Clinton, was completed in 1904. At Genoa the TPC&LS met the Lake Shore interurban which connected Toledo with Cleveland, and until it finished its own route into Toledo two years later, the TPC&LS entered the city over the tracks of the Lake Shore. In selecting a route from Genoa to Toledo the TPC&LS chose a round- about route which took it due north from Genoa through Clay Center to Curtice, then northwest through Booth, and finally east through Ryan, enter- ing Toledo on Starr Avenue over the tracks of the Toledo Railway & Light

(hereafter abbreviated OE papers). Copies of franchises granted by Oak Harbor, Port Clinton and Marblehead are in folder, "Toledo, Port Clinton and Lakeside," Box 132, OE papers. Each stipulated a maximum five-cent fare for travel wholely within village boundaries. Tourism development is covered in Commemorative Biographical Record of the Counties of Sandusky and Ottawa, Ohio (Chicago, 1896), 392, and Robert J. Dodge, Isolated Splendor: Put-In Bay and South Bass Island (Hicksville, NY, 1975), 71-107. The limestone blocks for Henry Ford's River Rouge mansion, Fare Lane, completed in 1915, came from Marblehead peninsula quarries. Craig Wilson, "Life in Michigan's Fare Lane," Akron Beacon Journal, July 26, 1992, Sec. F, 1, 3. |

128 OHIO HISTORY

Company. This entry took the road

through several minor villages not oth-

erwise served, but it added slightly

more than three miles and about fifteen

minutes to the more direct route from

Genoa to Toledo taken by the Lake

Shore. Clearly, the road's promoters

placed a higher value on maximizing

the population served than on speed of

service to and from the Marblehead

peninsula, a calculation unaffected by

the prospect of automobile competition

and the less forgiving definitions of

speed and convenience that accompanied

mass automobile ownership.6

The TPC&LS was an exceptionally

well-designed and well-built interurban.

Constructed with a solid roadbed and shallow

curves under the supervision of

railroad engineer Herbert C. Warren, the

road could support railroad freight

cars, facilitating traffic interchange

with steam roads. Its brick powerhouse,

located along the Lake Erie shore-line

at Port Clinton close to abundant cool-

ing water, and its electrical

distribution system received approving reviews in

Street Railway Journal and Railway Age, as didits attractive stations

in the

communities through which it passed. At

the same time, some components

showed more interest in economy than in

permanence: its 143,000 cross ties

and 3800 electrical distribution poles,

for example, were of untreated wood,

assuring earlier replacement than more

durable alternatives. On balance, how-

ever, there can be little doubt that the

road's promoters intended their invest-

ment to be long-lasting and they built

to a generally high standard.7

On February 20, 1907, the construction

company turned the completed road

over to the Toledo, Port Clinton &

Lakeside. The company received a single-

track electric interurban railway, 50.70

miles long with 3.15 miles of

turnouts and sidings, entering Toledo on

the east over the tracks of the Toledo

Railway & Light Company. The road

cost a total of $1,350,000 to con-

struct, an amount almost equal to the

face value of the $1,500,000 five per-

cent first-mortgage bonds. The

$1,800,000 in common stock, then, did not

represent tangible assets, and in the

language of the day, the TPC&LS was a

typically "watered"

corporation. Using the terminology of a more recent and

more tolerant generation, the road was

100 percent debt-financed through

"junk" bonds and highly

leveraged; its stock could attain value only if the

road developed a cash flow sufficient to

generate a healthy surplus for divi-

6. Hilton, 5-9, "Toledo, Port

Clinton and Lakeside," Street Railway Journal, pp 1130-32;

"TPC&LS Railroad Commission

Report," 1907-08, 16, 18, Box 157, OE papers. In Toledo the

company paid 3.5 cents per passenger

carried and a percentage of freight charges to the

Toledo Railway and Light Company for

trackage rights.

7. Hilton, 5-8; "The Toledo, Port

Clinton and Lakeside," 1130-38; "Toledo, Port Clinton and

Lakeside," Railway Age 41

(May 11, 1906), 794-96. "Annual Report of the Toledo, Port

Clinton and Lakeside Railway Company to

the Tax Commission of Ohio for the Year Ending

January 1, 1911" (hereafter

abbreviated "TPC&LS Tax Commission Report," 1910), 43, Box

156, OE papers. The company used 70

pound-per-yard T-rail, the customary weight in the

interurban industry. Ibid., Hilton and

Due, 48.

Interurbans in the Automobile

Age

129

dends after paying all operating

expenses, taxes, and the annual bond interest

charge of $75,000. How the bonds were

placed is not known. The stock,

however, remained in friendly hands,

with the construction company retaining

a third and company promoters and their

families controlling another 40 per-

cent. Most of the rest was held in lots

of twenty shares or less, primarily by

people in communities through which the

road passed; in many cases the

stock probably represented payment to

rural property owners for roadside right

of way.8

Although Street Railway Journal enthused

that the "features which go to

make an interurban line successful are

peculiarly combined" on the

Marblehead peninsula, success proved

elusive. While the road's promoters

projected summer tourism as a major

revenue source, the tourist season lasted

a scant three months. Terminating on a

peninsula, the railway could hardly

participate in intercity through

traffic, except indirectly via lake boat to

Sandusky across the bay, and then only

during the shipping season. The

largest village through which the road

passed, Port Clinton, the county seat

of Ottawa County, had a 1910 population

of 3,000. Hence the road would

have to rely for most of the year on

whatever local traffic rural Ottawa

County's 20,000 people could provide.

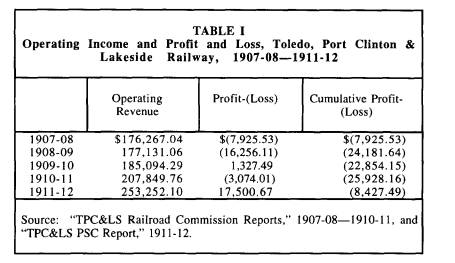

A review of the company's operation and

finances between 1908 and 1912

illustrates its inability to generate

sufficient traffic to cover its costs even be-

fore the automobile developed as a

serious competitor. Intended primarily as

a passenger road, the railway carried

782,766 revenue passengers for the year

July 1, 1907, through June 30, 1908,9

the first full year following entry into

Toledo, dipped to 738,413 in 1910-11 and

then climbed to 781,600 in 1911-

12. Passenger revenue ranged from

$120,200 in 1908-09 to $148,200 in

1911-12. Freight traffic showed more

consistent growth; revenues doubled

from $18,900 in 1907-08, to $37,800 in

1911-12.10

8. Hilton, 9; "TPC&LS Railroad

Commission Report," 1907-08, 11, 15, 59-60a, Box 156,

OE papers.

9. The Railroad Commission and its

successors, the Public Service Commission (PSC) and

Public Utilities Commission (PUCO),

required annual reports covering July 1 through June 30

of the following year until 1916 when

the PUCO changed to calendar year reporting. State

reports duplicated Interstate Commerce

Commission reports exactly and covered the same time

spans. PUCO and ICC reports required

financial and operating data. Reports to the Tax

Commission of Ohio included financial

and detailed property ownership data, but not operating

data, on a calendar year basis. Figures

often differ slightly from report to report, even when

covering the same time period, but

seldom by as much as one percent. To reflect this lack of

uniformity and precision, as well as to improve

readability, I have generally rounded figures to

the nearest hundred or thousand.

10. "TPC&LS Railroad Commission

Reports," 1907-08, 21, 45, 1908-09-1910-11, 35, 65,

"TPC&LS PSC Report,"

1911-12, 35, 65, Box 157, OE papers.

|

130 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

Even more impressive was the growth in electric sales, which increased 162 percent between 1907-08 and 1911-12, from $23,300 to $61,400, constitut- ing a full 24.2 percent of the latter year's operating revenues. Except for its major villages, the Marblehead peninsula was largely without electric service before the construction of the TPC&LS. Area limestone and gypsum quarries quickly contracted for power; others along the right-of-way followed. The vil- lages of Oak Harbor and Elmore supplied their municipal distribution systems with power purchased wholesale from the railway.11 As anticipated, railway traffic and revenue proved to be highly seasonal. Surviving monthly traffic figures from July 1910 through June 1912 show a base passenger load in the winter of fifty to sixty thousand passengers per month, rising through the spring and early summer to a peak of about 80,000 in August, and then dropping through the fall, with a second minor peak in the holiday month of December. In August 1911 the railway carried 82,534 passengers, 54 percent above the average (53,541) for January, February and March of that year; the December peak was 27 percent above the winter aver- age. Freight traffic showed a similar pattern, peaking during the height of the

11. Hilton, 11-12; "TPC&LS PSC Report," 1911-12, 35, 63 Box 107, OE papers; "Ohio Public Service, PUCO Report (Electric)," 1924, 9 Box 157, OE papers. In Elmore several plans to generate and sell electricity had gone awry; in April 1911 residents voted to build a municipal plant, but in November the city instead contracted for power with the TPC&LS and built its own distribution system. Grace Luebke, Elmore, Ohio: A History Preserved (Evansville, 1975), 227. |

Interurbans in the Automobile

Age 131

fruit harvest in September when the

company ran twice the freight car

mileage as it averaged in non-harvest

months.12

Revenue peaked even more sharply than

traffic. Tourists to peninsula and

island resort areas rode further and

paid higher fares than did Ottawa County

residents using the railway for local

travel. In 1911 the average fare paid be-

tween January and June was 14.5 cents,

indicating an average ride of slightly

more than seven miles at the typical

fare of two cents per mile, compared to

22.3 cents between July and December.

Hence the railway collected 65.9 per-

cent of its passenger revenue in the

second half of the year. Similarly, freight

charges per carload for handling

perishable crops were considerably higher

than for hauling bulk commodities such

as limestone and gypsum; in 1911

the TPC&LS earned 73.4 percent of

its freight revenue in the second half.13

The TPC&LS seems to have been as

well managed as it was well designed

and well built. A key measure of

efficiency is the ratio of expenses to rev-

enues, known as the operating ratio. If

operations were to consume all avail-

able revenue, there would be no

remaining funds to cover fixed costs such as

bond interest or to allow payment of

dividends on common stock. Operating

ratios above 60 percent tended to

squeeze earnings on all but the strongest

roads.14 Between 1907 and 1911

the TPC&LS maintained an operating ratio

of between 50 and 57 percent, a good

indication of competent management.

But the road never achieved the

financial stability such a favorable ratio im-

plied, as the company failed to generate

earnings sufficient to support its

heavy fixed charges. In spite of earlier

rosy projections, traffic and revenue

levels were disappointing and

insufficient to cover costs. The figures in

Table I (page 130) show that in spite of

prudent management the road earned

its expenses in only two of its first

five years and compiled a cumulative

deficit of more than $8,000. While the

road's position improved after 1910

as gross income increased, these

increases came almost entirely from im-

proved freight and electricity earnings.

Passenger income remained nearly

constant and declined as a percent of

gross income from 69.8 percent in 1907-

08 to 58.5 percent in 1911-12.15 The

sharp seasonality of the railway

business helped to keep earnings low. In

1912 the company was profitable

for the year with an operating ratio of

58.2 percent, but this represented the

12. Figures are taken from work sheets

used to total monthly traffic data pasted inside the

back covers of "TPC&LS Report

to the Railroad Commission," 1910-11 and "TPC&LS Report

to the PSC," 1911-12, Boxes 156-57,

OE papers.

13. Figures are taken from work sheets

used to total revenues and expenses by calendar

halves pasted onto the inside front

covers of Ibid.

14. Hilton and Due, 186-95.

15. "TPC&LS Railroad Commission

Reports," 1907-08, 21, 1908-09--1911-12, 35, Box

156-57, OE papers. In comparison, the

Lake Shore Electric Railway received 87.2 percent of

its 1911 income from passenger revenue,

and the Cleveland Painesville and Eastern 80.5

percent. Electric Railway Journal, 40

(August 17, 1912), 262; (September 21, 1912), 465.

132 OHIO HISTORY

average of an anemic 64.9 percent forthe

first half and a healthy 50.4 percent for

the second. Because of low demand and

idle capacity the company lost money

in the first half but then more than

made up for it in the second; whatever

profits the TPC&LS earned came

between the summer solstice andChristmas.16

The proceeds from the securities issued

in 1903 had to fund not only con-

struction but also bond interest

payments until the road began to produce in-

come. By the time the operating company

took possession of the road in

early 1907, funds were pretty much

depleted, and the lack of cash reserves,

coupled with the failure of the road to

earn expenses in its early years, created

severe financial stresses. Unable to

meet its full bond commitments consis-

tently, the company slowly fell behind

in its interest payments and then, in

1908-09, began to cover its delinquency

through short-term borrowing. By

June 1911 the company had reduced its

interest arrears to $16,625, but in do-

ing so had acquired $45,550 in

short-term debt. Only by juggling the de-

mands of short and long-term creditors

was the TPC&LS able to remain sol-

vent. 17

Dismal as are the figures in Table I,

they still understate the actual financial

situation of the TPC&LS. Mortgage

bonds invariably required the issuing

corporation to assure their eventual

redemption by contributing one to two

percent of the principal annually to a

sinking fund. As the bonds of the

TPC&LS came due in 1928, the company

needed to fund $1,500,00 by that

date. But as of 1911 the company had

made no deposits to a sinking fund,

and clearly lacked the means to do so.

Similarly, prudent accounting called

for the company to fund its depreciation

so that as parts of the system wore

out funds would be on hand to purchase

replacements. But the TPC&LS

maintained no depreciation reserve.

Barely able to meet current demands, the

company lacked the resources to make

prudent provision for future needs and

obligations.

These liabilities directly affected the

company's value as an investment. In

early 1912 the Ohio Tax Commission

questioned the company's failure to

state in its most recent annual report a

market value for its bonds and com-

mon stock. Responding for the company,

General Manager Theodore

Schmitt noted that neither set of

securities had ever been listed on an ex-

change and that he was unaware of any offers

for bonds "which would indicate

16. "TPC&LS Tax Commission

Report," 1912, pp, 55, 63, Box 156, OE papers;

"Northwestern Ohio Railway and

Power Company Tax Commission Report," 1912, 55, 63, Box

99, Ibid. It is possible to separate

data for 1912 into approximate calendar halves the

Northwestern Ohio Railway and Power

Company (NOR&P) bought the TPC&LS in July 1912.

The old company filed a report covering

January-July; the new company filed two reports, one

covering July-December, and one covering

the entire year.

17. "TPC&LS Railroad Commission

Reports," 1906-07, p 17, 1907-08, 13, 1908-09-1910-

11, 17, 21; "TPC&LS PSC

Report," 1911-12, 17, 21, Boxes 156-57, OE papers.

Interurbans in the Automobile

Age 133

a market price"; the stock, he

claimed, "has no market value." With no assets

backed by equity and no reasonable

prospect of earnings to apply to dividends,

it is difficult to argue with Schmitt's

somber conclusions.18

Others shared his pessimism. In 1912

Philadelphia banker Leslie M. Shaw

joined the company's board, its first

member from outside the Toledo area.

President of First Mortgage Guarantee

& Trust Company of Philadelphia,

Shaw undoubtedly represented bondholders

unhappy with the road's failure to

meet its interest and sinking fund

obligations and anxious to protect what re-

mained of their investment.19 In

1911-12 the company paid off its short-term

debt, but in the process fell a

disastrous $87,600 behind in its interest pay-

ments. Bondholder discontent seems to

have been the catalyst which shortly

thereafter forced the road's sale to

General Gas and Electric.20

The Middle Years, 1912-1924

General Gas and Electric Company, a

utility holding company based in

New York City, agreed to purchase the

Toledo, Port Clinton & Lakeside in

May 1912 for $1,100,000, a price the

purchaser explained to the state Tax

Commission as representing original cost

less accrued depreciation. After set-

tlement of the old company's

obligations, bondholders received about

$975,000, or roughly sixty-five cents on

the dollar; stockholders received

nothing.

Controlled by William S. Barstow,

General Gas and Electric owned utilities

in several eastern cities and supplied

transport as well as electric power in and

around Rutland, Vermont, and High Point,

North Carolina. Barstow formed a

new corporation, the Northwestern Ohio

Railway & Power Company, as a

wholely owned subsidiary of General Gas

and Electric. Capitalized much like

its predecessor, the NOR&P issued

five percent first mortgage sinking fund

bonds for the full purchase price of

$1,100,000 plus $500,000 in seven per-

cent preferred stock and $800,000 in

common. None of the securities were

sold to the public; all remained the

property of General Gas and Electric.

18. Irville A. May, Street Railway

Accounting: A Manual of Operating Practice for Electric

Railways (New York, 1917), 287-90; [Theodore Schmitt], General

Manager, TPC&LS, to R.

M. Dittey, Chairman, Tax Commission of

Ohio, March 27, 1912, letter folded inside front

cover, "TPC&LS Tax Commission

Report," 1911, Box 156, OE papers.

19. Before assuming the presidency of

First Mortgage Guarantee & Trust Company of

Philadelphia in 1909, Shaw had been a

lawyer and banker in Iowa, governor of that state from

1898 to 1902, and Theodore Roosevelt's

Secretary of the Treasury from 1902 to 1907. Albert

N. Marquis, ed., Who's Who in America

(London, 1910), 1727.

20. "TPC&LS PSC Report,"

1911-12, 5, Box 157, OE papers. The company's final state-

ment of current assets and liabilities

showed cash and accounts receivable of $14,900 against

current liabilities of $96,500. The

railway was all but bankrupt. "TPC&LS Tax Commission

Report," 1912, 23, Ibid.

134 OHIO HISTORY

Later in the year the NOR&P issued

an additional $193,000 in bonds to fund

a large power house addition, purchase

the small Port Clinton Light and

Power Company ($30,000), and make other

minor improvements. While the

stock of the NOR&P was as

speculative and dependent on future earnings as

was the stock of the TPC&LS, the

reduction in bond interest from $75,000

to $64,650 dropped the fixed charges that

had to be met before dividends could

be considered. At least as interested in

electric sales as transport, General Gas

and Electric followed its Marblehead

peninsula purchases with acquisition of

the Sandusky Gas and Electric Company

across Sandusky Bay.21

Purchasing the TPC&LS during its

best year, Barstow doubtlessly expected

recent earnings improvements to continue

into the future, and earnings did

improve in the second half of 1912 when

the railway paid bond interest, full

dividends on the seven-percent

preferred, and two percent on the common, al-

though it ran a small deficit to pay the

last. But dividends soon disappeared.

Beginning in 1914 rising costs and

declining revenues quickly reversed the

railway's fortunes, and in 1915 it

earned only $73,950 on operations and ran a

$4900 deficit after paying bond interest

and taxes.22

The reasons for the reversal were

fourfold. First, the inflation that accom-

panied World War I increased the prices

of all commodities including labor

and particularly coal, sharply raising

operating costs. Second, as the railway

aged the funds required for annual

maintenance of road bed, bridges and trestles

("way and structures")

increased more rapidly than inflation, from $8,200 in

1910, to $18,000 in 1915, and $45,500 in

1920. Third, the Marblehead

peninsula gradually lost its position as

the focal point of tourism in northern

Ohio, eclipsed after World War I by

flourishing Cedar Point on the south side

of Sandusky Bay. The TPC&LS

attempted to meet this challenge by leasing

and electrifying a spur of the

Marblehead and Lakeside Railroad to Bay Point

in 1911, thereby moving the terminus of

the line three miles south from

Marblehead and as close to Cedar Point

as peninsular geography would allow,

and by entering into seasonal joint

traffic agreements with lake steamers

which connected the railway with Cedar

Point, Sandusky and Cleveland.23

But the overriding reason for the decline

in the NOR&P's fortunes was the

increasingly widespread ownership and

use of the private automobile. As a

21. Hilton, 12-16, Electric Railway

Journal, 39 (June 1, 1912), 945; 40 (July 6, 1912), 38;

(July 27, 1912), 141; (September 28,

1912), 512; (November 16, 1912), 1043; Public Service

Commission Report, 1912, 540-45, 645-46; "NOR&P Tax Commission

Report," 1912, 72, Box

99, OE papers; "Sandusky Gas and

Electric, Tax Commission Report," 1913, 7, Box 143, OE

papers.

22. "NOR&P Tax Commission

Reports," 1912-1914, 15, and "NOR&P ICC Report," 1912-

13, 31, 35, Box 99, OE papers. The

NOR&P paid two percent on its preferred in 1913, 0.5

percent in 1914, and nothing on its

common.

23. "TPC&LS Tax Commission

Report," 1910, 47; "NOR&P Tax Commission Reports,"

1915, 61, 1920, 33, Boxes 99, 157, OE

papers; Hilton, 9-10.

Interurbans in the Automobile

Age

135

tourist road it was particularly

vulnerable to automobile competition as fami-

lies with automobiles, particularly in

rural areas, used them in preference to

available public transport for

recreation and pleasure. County fairs provide a

good example. In 1914 Electric

Railway Journal reported that while atten-

dance at agricultural fairs in the upper

midwest generally was above that of

the previous year, electric railway

patronage and revenues on lines serving fair

grounds were off sharply; an

accompanying illustration showed a field of

parked touring cars at the Fremont,

Ohio, fairgrounds.24

Similarly, the automobile expanded

vacation possibilities by increasing in-

dividual control over travel

arrangements. "Vacationing in a motor car is

quite the finest thing that has been

discovered," a Detroit newspaper observed

in 1915; "The expense is no greater

but the liberty is, for one does not have

to depend on time tables and be in a

rush."25 Interurbans dependent on tourist

traffic quickly felt the consequences. A

New England street railway president

told the Federal Electric Railway

Commission in 1918 that electric lines built

"through strictly summer resort

territory" in western Massachusetts had in re-

cent years lost up to two-thirds of

their patronage and in some cases been

abandoned. "Some years ago,"

he explained,

the tourists came in and spent a week or

a month in some favorite inn with an oc-

casional trolley trip through the hills.

Now the tourist comes in his automobile,

and depending upon his standing, a very

elaborate one or a very simple one, stays

a day or two and passes on to some other

part of the country. That has had a most

disastrous effect upon the revenue of

the electric lines in the territory. .. .26

Cedar Point, with its resorts, amusement

park and other attractions, profited

from these changing patterns in tourism.

Easily accessible by automobile

from northern Ohio's numerous industrial

cities and market towns in a broad

24. Michael L. Berger, The Devil

Wagon in God's Country: The Automobile and Social

Change in Rural America, 1893-1929 (Hamden, Conn., 1979), 103-26; "Effect of

Automobiles

on Interurban Transportation," Electric

Railway Journal, 44 (December 5, 1914), 1243.

Promoters considered county fairgrounds

to be important traffic builders. A never-built line

from Akron to Mansfield planned its

route to pass five. Electric Railway Journal, 33 (January

16, 1909), 121.

25. "Motor Cars Change Ideas of

Vacation, Greater Freedom," Detroit Free Press, July 11,

1915, Pt. 5, 8.

26. Testimony of Lucius S. Storrs,

President of the Connecticut Company, before the

Federal Electric Railroad Commission,

quoted in Delos F. Wilcox, Analysis of the Electric

Railway Problem, (New York, 1921), 101. A Wisconsin hotel executive

estimated that from

May to December "motor

tourists" constituted 75 percent of his hotels' transient business.

Walter Schroeder, "Concrete

Highways Bring Business to Wisconsin Hotels," Concrete

Highway Magazine, 8 (December 1924), 270-72. For the impact of the

automobile on tourism

in the White Mountains, see William L.

Taylor, "Getting There," in Richard Ober, ed., At What

Cost? Shaping the Land We Call New

Hampshire (Concord, 1992), 25-35; for

Glacier National

Park, see Douglas V. Shaw, "The

Great Northern Railway and the Promotion of Tourism,"

Journal of Cultural Economics, 13 (June 1989), 65-76.

136 OHIO

HISTORY

arc from Cleveland to Toledo, it

attracted a growing automobile trade from an

early date. On July 4, 1915, for

example, 3,500 patrons arrived by steamer,

3,500 by train, and 3,000 by automobile;

on the same holiday six years later

3,000 cars occupied parking spaces,

representing far more than 3,000 people.

Long stays in the Point's resort hotels

declined in importance, replaced by

many more people arriving for one-day

auto visits. As a result, traffic on the

NOR&P seeking to transfer to Lake

Erie steamers dwindled, and in 1925 the

line terminated its joint traffic

agreements with steamer companies and aban-

doned its extension from Marblehead to

Bay Point.27

Summer tourist traffic began to desert

the NOR&P in 1912 or shortly

thereafter. Total annual passenger revenue

peaked in 1913-14, but total pas-

senger numbers did not peak until

the following year, consistent with slight

increases in local use set against

modest declines in seasonal long-distance

travel, such as Toledo residents

visiting resort areas on the peninsula and adja-

cent islands.28 Surviving

monthly traffic figures from 1917 suggest the ex-

tent of the decline in summer tourist

patronage. August continued to be the

railway's busiest month in 1917, but in

contrast to 1911, when the August

peak was 54 percent above the

January-to-March average, the August peak in

1917 was only 17 percent above the

winter average. While winter patronage

in 1917 exceeded that of 1911 by 13.9

percent, August 1917 patronage fell

9.2 percent below that of August 1911.29

The rapid decrease in tourist traffic

accompanied a severe but more gradual

falling off of patronage generally.

Peaking in 1914-15 at 934,000, ridership

began a long secular decline which

continued with only occasional interrup-

tion until the end of passenger service

in 1939. By 1918 the number of rev-

enue passengers had fallen to 656,000,

the lowest in the road's history.

Traffic stabilized near 600,000 through

1921 but then began to fall again,

reaching 492,000 in 1923, a mere 53

percent of the 1914-15 high.30

27. David W. and Diane D. Francis, Cedar

Point: The Queen of American Watering Places

(Canton, Ohio, 1988), 56-57, 72-73, 82.

28. "NOR&P ICC Reports,"

1914-15 and 1915-16, 403. Evidence from the company's

annual reported revenues from handling

baggage confirms these conclusions. Baggage rev-

enue peaked in 1911 at $1,442, fell

slightly to $1,372 in 1912, and then began a more dramatic

slide, to $1,210 in 1913, $1,056 in

1914, and $806 in 1916. The drop in baggage revenue would

seem to provide a rough proxy by which

we can gauge the decrease in long-term tourist

traffic. "TPC&LS and NOR&P

Tax Commission Reports," 1910-1916, 55, Boxes 99 and 157,

OE papers.

29. Monthly figures from work sheet

folded inside back cover of "NOR&P ICC Report,"

1917, Box 99, OE papers.

30. "NOR&P ICC Reports,"

1914-15, 65, 1915-16--1923, 403, Boxes 99-100, OE papers.

These figures differ from those given by

Hilton as he did not take into account that the com-

pany filed two reports in 1916, one on

June 30 and one on December 31. Hence Hilton's

figures beginning with 1917 are ahead by

one year. See Hilton, 16.

Interurbans in the Automobile

Age 137

Interurbans all over the country

experienced similar declines as automobiles

increased in number and as improved

roads expanded their range. Electric

Railway Journal noted the impact of the automobile on traffic as early

as

1911. In an unnamed Indiana town of

8,000 connected by interurban to a

nearby city of 20,000, it claimed, there

were thirty-five automobiles.

Through 1910 the railway "derived a

very gratifying income from the town,"

but now, "owners of machines go to

the city in their autos and invite their

neighbors to accompany them, and the

company loses not only the business

of the owners but that of many [other]

persons besides." Similarly, a Texas

railway official noted in 1917 that in

small towns, "where everyone seems to

know everyone else," automobile

owners hailed their friends waiting at in-

terurban stops and carried them free to

their destinations. The most common

reason for cashing in an unused leg of a

round-trip ticket, he maintained, was

"'made the trip in an

automobile."' Thus the impact of automobile use on

rail patronage had the potential to

extend well beyond the community of own-

ers.31

Automobile ownership expanded most

rapidly in prosperous rural and

small-town areas of the Midwest. Ottawa

County was no exception. County

residents owned 3,382 registered

automobiles in 1922, a figure which grew 76

percent to 5,944 in 1926, or one auto for

every 3.57 persons. As access to

automobiles increased, as paved roads

connected the county's farms and vil-

lages with each other and with places

more distant, the relative importance of

public transport diminished.32

Between 1923 and 1926 traffic on the

NOR&P declined another 41 percent,

from 492,000 to 290,000, a direct result

of increased automobile use. Unlike

many other Ohio interurbans, the

NOR&P remained relatively free of motor

bus competition along its route as that

industry developed after 1915. Only

in the Port Clinton area did buses

compete directly. A line connecting Port

Clinton with Fremont and Tiffin

paralleled the railway for several miles be-

fore turning south, and in 1921 service

with a single vehicle began between

Port Clinton and Gypsum, four miles

further east along the peninsula.33

31. "Automobiles Affect Interurban

Traffic," Electric Railway Journal 38 (August 26,

1911), 370; James P. Griffin, "The

Influence of the Automobile on the Interurban," Ibid., 49

(May 5, 1917), 820.

32. Berger, 77-94; "Anticipated

Progress, 1927-1937, The Toledo Edison Company"

(typescript), 1927, 18, Box 134, OE

papers; The Ohio Public Service Company, "Market

Analysis of the Securities Sales

Territory" (typescript), 1926, Table X, Box 135, OE papers.

33. "NOR&P ICC Report,"

1923, 403, Box 99, OE papers; Ohio Public Service Division

Operating Reports, 1927-1930, Box 129,

OE papers; "Motor Bus Reports," 1926, 1931,

Records Group 1496, Ohio Historical

Society, Columbus, Ohio. A 1922 review of the Ohio

intercity bus industry confirmed the

lack of competition with the NOR&P. "Birdseye View of

Ohio Buses," Bus Transportation,

1 (March, 1922), 173-81.

138 OHIO HISTORY

More troubling than the motor bus was

the motor truck. Just as interur-

bans had used their greater convenience

and flexibility to take some of the

less-than-carload freight, package

express and perishable commodity traffic

from steam railroads, motor trucks used

their even greater flexibility and

lower costs to undercut electric

railways and to edge them out of the various

specialized niches they had found in the

movement of freight. As with the

motor bus, serious motor truck

competition began around 1915 and grew

rapidly in the 1920s as roads and

vehicles improved.34

From its inception the promoters of the

TPC&LS had looked to the or-

chards and truck farms of the Marblehead

peninsula as a major revenue source,

and as we have seen, heavy freight

traffic in the early fall represented the rail-

way's participation in those harvests.

But this type of traffic was particularly

susceptible to truck competition as

trucks could load in every farm yard and

drive directly to Toledo markets and

freight houses, eliminating the haul from

farm to railway loading dock. In the

early 1920s the NOR&P encountered se-

rious competition from local truck lines

and reduced its rates at the beginning

of the 1922 season in an attempt to

maintain its position in transporting the

fruit harvest to market.35

The growth and decline of the NOR&P

as a milk hauler more clearly doc-

uments the impact of the motor truck on

the carriage of perishable farm

commodities. Few products require more

rapid handling than unrefrigerated

raw milk, and interurbans proved

superior to both railroads and horse-drawn

wagons in moving milk from farm to

market. Farmers with access to in-

terurbans took advantage of improved

transport links, and dairy production

generally increased along interurban

lines. Like other interurbans, the

NOR&P built platforms along its

right-of-way on which dairy farmers left

milk in standard five, eight, and

ten-gallon cans. To each can farmers tied a

prepaid ticket and a return address tag;

for rates which in 1920 ranged from

12.5 to 28.5 cents per can depending on

can size and distance, the railway

picked up the cans, carried them to

Toledo and returned the empties.36

Although Ottawa County was not a major

milk producer, the NOR&P

built up a small but respectable

business. Receipts grew from $700 in 1909

to $1200 in 1914, to $3450 in 1918.

Peaking at $6250 in 1920, receipts fell

to $3550 in 1923, the last year for

which figures are available. The NOR&P

34. Pease, 35; William R. Childs, Trucking

and the Public Interest: The Emergence of

Federal Regulation, 1914-1940 (Knoxville, 1985), 7-43.

35. "Special Rates Being

Arranged," Electric Railway Journal 60 (July 1, 1922), 30; John

M. Killets, Toledo and Lucas County,

1623-1923, Vol. I (Chicago and Toledo, 1923), 557.

36. Northwestern Ohio Railway and Power

Company, Local Milk Tariff, October 30, 1920,

in "Rates and Tariffs for Railway

Service, The Ohio Public Service Company," Box 134, OE

papers. See also Pease, 9-11; Bogart,

598-99; G. W. Parker, "Transportation of Milk and

Cream," Electric Railway Journal

36 (December 24, 1910), 1237-38; and "Transportation of

Freight," Ibid., 42 (October 4,

1913), 601-02.

|

Interurbans in the Automobile Age 139 |

|

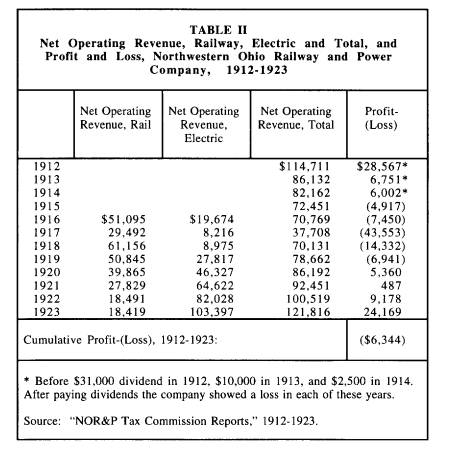

experience, however, mirrored that of interurbans around the state. Milk rev- enue for all Ohio interurbans grew from $152,000 in 1909 to $290,000 in the peak year of 1920, and then began to fall rapidly, to $212,000 in 1923, $87,000 in 1927, and $15,000 in 1930. Within ten years the greater speed, flexibility, and convenience of the motor truck edged interurbans almost com- pletely out of the milk trade.37 Falling ridership and revenue in the face of rising costs after 1915 brought the NOR&P to a state of acute financial distress. As Table II (page 139) shows, net operating income (income after operating expenses but before

37. "Statistics, Electric Interurban Railroads," Railroad Commission Reports, Public Service Commission Reports, and PUCO Reports, 1909-1930, various pages; Frank A. Cannon, "What Good Roads Do for the Dairy Business," Concrete Highway Magazine, 2 (June 1918), 125. |

140 OHIO HISTORY

bond interest and taxes) peaked in 1912

at $114,700 and then began to fall.

As net income fell, the railway's

operating ratio, the percentage of revenues

required to fund operations, rose, from

58.2 percent in 1912, to 69.6 percent

in 1915, and 86.1 percent in 1917. By

1915 net income after operating ex-

penses no longer covered fixed costs,

and the company lost $4,900. Losses

increased 50 percent to $7450 in 1916

and then escalated to a disastrous

$43,550 in 1917 when railway operating

costs rose 24.1 percent while rev-

enues rose only 6.8 percent. Power costs

jumped 45 percent above those of

1916, primarily the result of sharply

higher coal prices, and labor rose 22 per-

cent. While other items increased more

modestly, these two alone represented

increased annual costs of more than

$23,000. As earnings declined the com-

pany ceased to be able to cover its full

bond interest payments, and between

1918 and 1923 fell $101,000 behind.38

Like other Ohio interurbans, the

NOR&P responded to increased costs by

attempting to raise fares. It eliminated

discounts and applied to the PUCO to

boost maximum fares from two cents to

three cents a mile. Granted the in-

crease in July 1918, the NOR&P

immediately raised its fares to the new max-

imum.39 Higher fares,

however, did not have the desired impact on the rail-

way's balance sheet. Ridership in 1919,

the first full year in which the new

fares were in effect, was 24 percent

below 1917 levels; consequently 1919

passenger revenue rose only 13 percent

above that of 1917. At the same

time, the railway made only nominal cuts

in service, running its cars with in-

creasing numbers of empty seats. To

attract traffic the railway began in 1922

to discount the fares it had worked so

hard to secure in 1918, offering books

of tickets discounted 20 percent and

low-priced weekend excursions. In spite

of the company's best efforts, however,

patronage continued to decline and

railway net revenue fell steadily, from

$61,000 in 1918 to $18,400 in 1923

(see Table II). Net income from railway

operations in 1922 and 1923 was not

sufficient to pay the annual taxes on

the property.40

While demand for NOR&P rail services

dwindled, demand for power and

light grew from year to year. From its

beginning the TPC&LS carried on a

successful sideline in the sale of

electricity, and under NOR&P ownership

that business expanded steadily, with

the most rapid growth coming after

38. "NOR&P Tax Commission

Reports," 1915-1920, 55, 61-63, 71, 73, 79; 1921-1923, 27,

33-35, 43, 45, 51. In addition, the

NOR&P made no required contributions to a bond sinking

fund and did not begin a depreciation

reserve until 1920. "NOR&P ICC Reports," 1918-1923,

206, 232; C. C. Cash to the ICC,

November 4, 1922, letter, inside 1922 Report, Boxes 99-100,

OE papers.

39. PUCO Report, 1918, 141-43;

"Three Cents a Mile for Interurbans" Electric Railway

Journal, 51 (June 8, 1918), 1099-1100; "Ohio Interurbans

Act," Ibid. (June 29, 1918), 1254;

"Increase for Ohio

Interurbans," Ibid., 52 (July 20, 1918), 133.

40. "New Schedules and Fares

Announced," Electric Railway Journal 59 (June 3, 1922),

915. "NOR&P ICC Reports,"

1918-1923, 301, 403, Boxes 99-100, OE papers.

Interurbans in the Automobile

Age

141

World War I. Total sales rose from

$57,400 in 1913, to $82,600 in 1918, to

$302,500 in 1923, and the number of

customers grew from an estimated 300

in 1912 to around 3,000 in 1924. By the

mid-1920s power and light was

more than a sideline.41

Selling electricity improved railway

earnings in several ways. Electric

railways were rather inefficient users

of power plant capacity as their opera-

tion necessarily involved high peak

demand relative to average demand.

Hence railway power houses required

large reserve capacities to meet peak de-

mand. By selling electricity to

additional users with varying peak hours, the

ratio of peak demand to average demand tended

to fall, raising what the indus-

try calls the "load factor;"

higher load factors increased production efficiency

and lowered unit costs. Before 1910, in

spite of low load factors, railways

commonly generated their own power

because only in the largest cities did in-

dependent generating capacity exist

which might supply their needs. After

1910, as societal demands for power and

light grew, railways tended to be-

come either net sellers of electricity

to others, satisfying that demand, or net

purchasers, phasing out their own power

houses and integrating their idiosyn-

cratic loads into the more diversified

loads of larger producers serving many

consumers. Either way railways

benefitted through lower unit costs for the

power they consumed, but railways which

sold electricity gained the addi-

tional benefit of the revenue and profit

which that commodity earned.42

In the long run the future lay with

power sales. By the end of the 1920s

railway transport was a distressed

industry almost everywhere, while electric

light and power demand continued to

expand steadily. Akron-based Northern

Ohio Traction and Light, for example,

passed a milestone in 1919 when more

than 50 percent of net revenue

came from power sales, and it reached a major

turning point in 1926 when the electric

division for the first time earned the

majority of gross revenue. In

that year the company changed its name to

Northern Ohio Power and Light,

eliminating the association with transport,

and four years later shed its

increasingly marginal urban and interurban trans-

port divisions and renamed itself Ohio

Edison.43

41. "NOR&P Tax Commission

Report, 1913, 55, 1918, 69, 1923, 21 (elec.); "Anticipated

Progress, 1930-1937, The Ohio Public

Service Company," June 1930 (typescript), Box 134, and

Ohio Public Service, "Market

Analysis of the Securities Sales Territory," December 1926

(typescript), Box 135, OE papers.

42. Harold L. Platt, Electric City:

Energy and the Growth of the Chicago Area, 1880-1930

(Chicago, 1991), 95-138; Samuel Insull,

"The Relation of Central Station Generation to

Railway Electrification," Electric

Railway Journal, 40 (July 6, 1912), 12-19; C. N. Duffy, "The

Effect of Load Factor on Cost of

Electric Railway Passenger Service," Ibid., 41 (February 1,

1913), 195-96; "Selling Energy

Along Interurban Railways," Ibid., 48 (October 28, 1916), 920-

25; "Helping Out the Passenger

Earnings," Ibid., 50 (September 1, 1917), 349-50; Charles H.

Jones, "Power Facilities,"

Ibid., 64 (September 27, 1924), 493-97.

43. James M. Blower and Robert S.

Korach, The N.O.T. & L Story (Chicago, 1966), 8-9;

142 OHIO HISTORY

The NOR&P followed a roughly similar

course on a much smaller scale.

Hurt by high coal prices in 1917 and

1918, electric earnings emerged there-

after as the heart of the company (see

Table II). Each year the NOR&P ex-

panded its area of service; indeed, the

company listed in its reports the receipt

of between four and seven thousand

dollars in income annually as "donations"

from private parties seeking line

extensions. In 1920 net operating income

from electricity exceeded that of the

railway, and in 1923, the company's best

year since 1912, 52 percent of gross

revenues, 85 percent of pre-tax net rev-

enues, and 100 percent of after-tax net,

came from electric sales. The

NOR&P had returned to profitability,

but as an electric utility tethered to a

money-losing railway subsidized by

electric earnings.

In 1924 the company set out to break

that tether and end the subsidy.

Drawing up plans to separate the railway

and electric divisions into separate

co-owned corporations, company directors

planned to retire the 1912 railway

bonds and to issue new mortgage bonds

secured only by the electric proper-

ties. As an independent entity the

railway would purchase power from the

electric company. But the railway could

hardly stand alone. Unable to earn

even its taxes, it would quickly fail,

and like other failed interurbans in the

1920s, just as quickly be abandoned. It

seems clear from the record that the

NOR&P sought to detach the railway

from the power business in order to

scuttle it. Although approved by the

PUCO, the reorganization was not im-

plemented.44 Instead,

Barstow's General Gas and Electric received and ac-

cepted an unsolicited offer to purchase

both the NOR&P and Sandusky Gas

and Electric.

Years of Decline, 1924-1939

The purchaser, Ohio Public Service,

deserves detailed attention. Utility

magnate Henry L. Doherty followed his

1913 acquisition of The Toledo

Railway & Light Company (which split

in 1920 into Community Traction

and Toledo Edison) with the purchase of

several small utilities forming an ir-

regular crescent thirty to eighty miles

from Cleveland, and encompassing

Warren, Alliance, Massillon, Mansfield

(where the company also supplied

traction), Ashland, Elyria, and Lorain.

As electric demand grew, each local

generating plant began to push the

limits of its production capacity. In 1921

Doherty merged all of these companies

into Ohio Public Service, wholely

Northern Ohio Power and Light, Annual

and Monthly Operating Reports, 1919-1930, Boxes

22-25, OE papers.

44. "Application to P.U.C.O., March

13, 1924," carbon copy folded inside back cover of

NOR&P Director's Minute Book,

January 10, 1921 to April 17, 1925, n.p.,

Box 98, OE papers;

PUCO Report, 1924, 108.

Interurbans in the Automobile

Age 143

owned by his Cities Service holding

company, with the intent of connecting

the cities with high-tension lines and

supplying them with power produced in

plants located on Lake Erie where

abundant cooling water and ease of coal de-

livery assured low generation costs.

Additionally, as peak demand occurred at

different times in each locality, the

reserve capacity required by an inter-con-

nected system would necessarily be less

than the sum of the reserves required

for each of the localities standing

alone; the more diversified load of several

cities would provide a higher load

factor for an integrated system than any

single city could achieve individually.

Hence inter-connection reduced the

need for reserve capacity, allowed

maximum production at low cost plants,

and increased overall system efficiency.45

Quickly integrating its system and

concentrating power production in large

lake-shore plants near Lorain, OPS in

1923 began to explore expansion

prospects. A Cleveland consultant hired

to analyze the Ohio utility industry

identified Barstow's Sandusky Gas and

Electric as a particularly strategic ac-

quisition. An industrial city set in a

prosperous agricultural region, Sandusky

would furnish a large and diverse load,

and the property would forge a link be-

tween OPS territory in Lorain and Elyria

to the east and co-owned Toledo

Edison to the west; Toledo Edison, the

consultant recommended, should ac-

quire the NOR&P for its Ottawa

County electric territory. In September

1924 OPS bought both companies,

solidifying Doherty's position along the

lake shore west of Cleveland.46

Ohio Public Service paid General Gas and

Electric $2,755,000 for the

NOR&P, an enormous price. Earlier in

1924, when the NOR&P sought

PUCO approval for its restructuring, the

commission placed a value of

$1,013,000 on its electric properties.

In structuring its purchase, OPS paid

$1,105,000 for the electric assets and

$1,650,000 for the railway, an amount

just about equal to what the NOR&P

claimed as its original cost plus im-

provements. Yet no astute investor would

offer that amount for the railway

alone; by 1924 it was more liability

than asset, as General Gas and Electric

implicitly recognized in its plan to

reorganize and recapitalize the NOR&P.

45. "[Toledo Edison],"

(untitled bound report containing history and analysis of company

operations), 1940? Box 135, OE papers;

Henry L. Doherty & Company, "A Suggested Plan for

the Development of the Ohio Electric

Properties," November 1, 1919 (typescript), Box 134,

OE papers; William A. Duff, History

of North Central Ohio, Vol. I (Topeka, 1931), 247-50;

Thomas P. Hughes, Networks of Power:

Electrification in Western Society, 1880-1930

(Baltimore, 1983), 291-93; David E. Nye,

Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New

Technology, 1880-1940 (Cambridge, 1990), 182.

46. H. A. Fountain, "The Ohio

Public Service Company, Electric Territory, Preliminary

Survey," May 31, 1923 (typescript),

17-18, Box 134, OE papers. Fountain believed Barstow's

properties were developed below their

potential and that the Sandusky purchase had the

additional benefit of preventing rival

Ohio Power, operating in Tiffin and Fremont, from

reaching the lake.

144 OHIO

HISTORY

By purchasing the railway at close to

its book value, OPS in effect paid a

premium for the Ottawa County and

Sandusky electric territories. OPS

wanted access to new markets, and if in

the process it had to acquire an unpro-

ductive railway at a price unrelated to

its investment value, it was prepared to

do so.47

Company actions soon after support this

conclusion. Within a year of ac-

quiring the NOR&P and Sandusky Gas

and Electric, OPS tied the Marblehead

peninsula to Sandusky by means of

high-tension lines under the bay and

closed the Port Clinton power house. It

then connected Sandusky to its

Lorain generating stations to the east

and to Toledo Edison to the west, inte-

grating its new properties into a

growing regional power grid, and closed the

Sandusky power house.48 Although

OPS considered its primary business to

be "the production, transmission,

distribution and sale of electric energy" and

its transport facilities to be

"incidental to the acquisition of its electric proper-

ties," it made a good faith effort

to operate its railways in the public interest

in spite of continuing losses; it did

not capitalize them apart from the electric

properties and issued no securities

against them. In 1925 its Mansfield and

Port Clinton properties together lost

$28,500 on operations and $70,750 after

taxes, losses easily covered by a net

income of $3,312,000 from the sale of

electricity, electrical appliances, and

natural gas.49

On the Marblehead peninsula passenger

trends continued much as they had

since World War I. As travel moved to

the automobile, patronage on OPS

fell 55 percent between 1923 and 1929,

from 492,000 to 218,500. In spite of

this decline, however, the company

maintained service levels, reducing sched-

uled passenger mileage only by 14

percent. To encourage ridership, OPS re-

duced round-trip and children's fares in

1927, and in 1929 began bus service

with two leased 21-passenger buses,

connecting Port Clinton and Marblehead

with Sandusky across the recently

completed Bay bridge. But this service

47. "Northwestern Ohio Property

Passes to Doherty," Electric Railway Journal, 64 (August

2, 1924), 183; PUCO Report, 1924, 108;

"OPS Tax Commission Report," 18, Box 109, OE

papers. Because the price OPS paid for

the railway did not exceed the value of its physical

assets, the PUCO accepted the figure,

even though it bore no relation to the present or probable

future earnings potential of the

property.

48. "The Cities Service Power and

Light Company, Ohio System, Summary--O.P.S. and

A.P.S. Section, Plant Capacity,"

October 9, 1940 (typescript), n.p., Box 135, OE papers.

Before purchasing the Barstow properties

OPS verified that it could import power from Lorain

more cheaply than producing it in

Sandusky and Port Clinton. Henry L. Doherty & Co.,

"Report on Sandusky Gas &

Electric," July 3, 1924 (typescript), Box 145, OE papers.

49. "History and Business,"

n.d. (prob. 1937; appears to a fragment of a draft of an SEC

submission), Box 134, OE papers;

"OPS ICC Report," 1925, 301, 303, Box 110, OE papers. Six

percent of the company's $3,312,000 net

income in 1925 came from the sale of electric

appliances, ten percent from natural

gas, and 84 percent from electricity. Pre-tax transport

losses reduced net income by less than

one percent.

Interurbans in the Automobile

Age

145

drew far fewer patrons than the minimum

necessary to cover costs, and the

company gave it up after a six-month

trial and operating losses of $10,900.50

The decline in passenger traffic was

offset to some extent by steadily in-

creasing freight traffic. Although

interurbans tended to lose freight traffic dur-

ing the 1920s, the unusual role of OPS

in hauling mine products from the

Marblehead peninsula to Toledo railroad

connections gave it a traffic for

which motor trucks could not readily

compete. In 1926 freight revenue

reached $111,600, exceeding passenger

revenue (which decreased to $92,800)

for the first time. While freight

produced the majority of revenues, passenger

service accounted for most operating

costs. The railway ran 440,000 passen-

ger miles in 1929 and 105,000 freight

miles. Each freight mile produced

$1.05; each passenger mile only 17.7

cents. As operating costs averaged

34.0 cents per revenue mile, the

conclusion seems inescapable that freight

earnings subsidized passenger service.51

In the late 1920s the seasonality that

had characterized passenger and freight

traffic since the railway's inception

all but disappeared. In 1926 the number

of revenue passengers carried in August

equalled only 84 percent of the winter

average, and after 1926 the railway no

longer added extra cars to its summer

base schedule to handle anticipated

heavier traffic loads. Yet the link to

tourism was not completely lost. In

spite of the low August passenger count

in 1926, revenue collected from

passenger fares was the highest of any month

that year. The average August rider paid

39.7 cents, 34 percent above the

January average of 29.5 cents. The

longer average rides of summer tourists

continued to affect revenue patterns,

even if those tourists were now compara-

tively few in number. August revenue

peaks persisted through 1938, the last

summer of passenger service, although in

each year the railway attracted its

greatest number of patrons per month in

the winter when it functioned as a

cold-weather substitute for the private

automobile.52

The traditional September harvest-season

freight peak also faded. While

September freight revenues in 1926 were

28.4 percent above the average for

the year, that figure dropped to 22.0

percent in 1927; in 1928 September

50. "NOR&P ICC Report,"

1923, 403, Box 100, OE papers; OPS Division Operating

Reports, 1927-1930, Box 129, OE papers;

"Motor Bus Reports," 1929, 1930, Records Group

1496, Ohio Historical Society; Hilton,

23; "Rates and Tariffs for Railway Service, The Ohio

Public Service Company," Box 134,

OE papers. The railway did not reduce its "corpse rate"

in 1927, keeping it at $3.00 between any

two stations, with no discounts to encourage regular

riding. The corpse had to be in a casket

and the casket in a "rough box," accompanied by "a

person in charge" who carried

applicable permits and paid the regular fare.

51. OPS Division Operating Reports,

1927-1930, Box 129, OE papers. These monthly re-

ports give operating statistics for each

division, electric, gas and transport. As each report

included year-earlier figures, the 1927

reports include 1926 comparative information. These

are the first monthly figures available

after those of 1917. OPS ended freight and package

express service on its

Mansfield-to-Shelby interurban in 1925. PUCO Report, 1925, 232.

52. OPS Division Operating Reports,

1927-1938, Boxes 129-30, OE papers.

146 OHIO HISTORY

freight revenues were somewhat below the

year's average, indicating the loss

of virtually the entire fruit and

produce crop to the motor truck. Increasingly

dependent for revenue on the bulk

shipment of minerals from the Marblehead

peninsula, the railway more and more

resembled a short-line steam railroad.

Perhaps for this reason OPS explored

converting the railway to steam in

1926, but lost interest when it discovered

that its village franchises forbade

steam operation on local streets.53

The steady ridership declines of the

late 1920s eventually led to sharp cut-

backs in service. In January 1930 OPS

reduced its base schedule to require

five cars rather than six, and a year

later cut back again from five to three.

Annual mileage dropped 36 percent, from

426,000 in 1929 to 271,000 in

1932, the first full year of reduced

service. Infrequent schedules and economic

hard times accelerated the decline in

ridership; patronage dropped 69 percent

between 1929 and 1932, from 218,500 to

67,700. The depression affected

freight service similarly, with revenues

falling 61.5 percent between 1929 and

1932; indeed, 1932 combined passenger

and freight revenues were the lowest

in the railway's twenty-five year

history. Only by slashing service and main-

tenance expenditures did OPS avoid

losses on operations.54

The rest of the 1930s were equally

bleak. Passenger counts fell to 57,000

in 1933, rose slowly to 77,500 in 1936,

and then began to fall again, reach-

ing a new low of 49,000 in 1938. In

hopes of generating ridership, OPS of-

fered heavily discounted fares which

rewarded regular patrons. A book of

twenty-five tickets for the four-mile

trip between Port Clinton and Gypsum

sold in 1934 for $1.50, a cost of six

cents per ride or 1.5 cents per mile; a

year later a book of forty tickets for

the eleven miles from Oak Harbor to Port

Clinton sold for seven dollars, roughly

the same cost per mile. In 1937 the

company offered a $1.50 weekend

round-trip fare between Toledo and

Marblehead, and a $1.00 Sunday-only

fare, a price justifiable only on the

grounds that hauling low-fare passengers

added more value than hauling

empty seats. But even at these prices

the railway could not compete success-

fully with the private automobile.55

Bus competition also affected revenues

in the 1930s. By mid-decade

Greyhound connected Toledo with Oak

Harbor on a long local route that ter-

minated in Delaware, Ohio, and in

February 1938 Gottleib Schuster put three

hundred dollars down on a second-hand

eleven-passenger bus and began busi-

ness as Port Clinton Coach Lines.

Connecting Port Clinton with Bowling

53. Ibid., 1927-1930; unsigned memorandum

to T[heodore] O. Kennedy, February 22,

1926, "Toledo Port Clinton and

Lakeside" folder, Box 132, OE papers.

54. OPS Division Operating Reports,

1929-1932, Box 129, OE papers; Delta [an employee

oriented company periodical], VIII

(January 23, 1931), 3, Box 138, OE papers.

55. "Rates and Tariffs for Railway

Service, The Ohio Public Service Company," Box 134,

OE papers.

Interurbans in the Automobile

Age 147

Green, Schuster paralleled the railway

for twenty miles from Port Clinton to

Elmore. Shortly thereafter Schuster

revived the route attempted by OPS ten

years earlier, linking Port Clinton,

Marblehead and Sandusky with one six-

teen-passenger bus, but gave that up the

following year in favor of a route

from Marblehead to Toledo. In 1939

Schuster cleared $1,900 after expenses;

with his minimal capital investment and

the relatively low operating costs of

small buses, he could eke out a

respectable living from a level of traffic far

below the minimum required to sustain an

interurban railway.56

By 1938 OPS had reduced its service to

six runs each way, at roughly two-

hour intervals between six in the

morning and six at night. In early 1939

Community Traction announced it would

convert its Starr Avenue streetcar

line to motor bus, eliminating OPS's

rail entry into Toledo. Choosing to

abandon passenger service rather than

terminate at the city line with a transfer

to city buses, OPS made its last

passenger run on July 11th.57

A review of the final twelve months of

passenger operation illustrates the

futility of continuing service. From

July 1, 1938, through June 30, 1939,

the railway operated 188,000 miles of

passenger service and carried 46,600

passengers, slightly less than five

percent of the 1914-15 peak. Collecting

$12,675 in fares, the railway produced a

meager 6.7 cents of revenue per mile

operated. Cars traveled almost empty.

With an average fare of twenty-seven

cents, the average ride did not exceed

fifteen miles. Spreading 46,600 passen-

gers riding fifteen miles apiece over

188,000 miles of scheduled service pro-

duced an average passenger load of 3.71

patrons riding in cars designed to seat

fifty-six. Not surprisingly, in spite of

freight revenues of $61,000, the rail-

way lost $11,900 on operations with an

operating ratio of 116 percent, mean-

ing the company spent $1.16 to produce

each dollar of revenue.

A comparison with the twelve months

following the cessation of passenger

service illustrates the heavy losses the

passenger business must have incurred

for many years. While freight revenues

increased to $106,000, blurring an

exact comparison, expenses still fell

from $86,000 to $65,700 and the road

achieved an operating ratio of 61.5

percent, its most favorable showing since

1912. In spite of increased freight

activity, power and labor costs each fell

about 50 percent, a combined $17,500.

Without the high costs and low rev-

enues of passenger carriage, the railway

could, in a prosperous year, cover the

expenses of its freight service.58

Given the extremely low levels of

patronage during the 1930s, it is reason-

able to ask why the company continued

passenger service until it literally lost

56. "Motor Bus Reports," 1938,

1939, Record Group 1496, Ohio Historical Society; "News

of the Road," Bus

Transportation, 23 (November, 1944), 69.

57. Hilton, 25, 28.

58. OPS Division Operating Reports,

1938-1940, Box 130, OE papers.

148 OHIO HISTORY

its way in Toledo in 1939. An internal

study in 1935 found transport to be

"of minor importance" to the

company, with service continued "only for rea-

sons of public policy and convenience of

the public as there is no possibility

of profiting from these

operations." In all likelihood the company considered

the provision of transport at a loss as

a means of maintaining good public re-

lations in an electric territory and a

way to mitigate the growing criticism in

the 1930s of utilities and utility

holding companies. There is no indication

that OPS ever envisioned a resurgence in

the fortunes of interurban rail trans-

port.59

As OPS anticipated when it purchased the

NOR&P in 1924, electricity

proved to be a far more lucrative

product than transport, with sales rising

from $302,500 in 1923 to $374,000 in

1925. OPS then reduced its Port

Clinton service district by about a

third, selling the portion closest to Toledo

to co-owned Toledo Edison. To manage

growing demand, OPS followed

connection to Lorain generating plants

with a complete rebuilding of its

Marblehead peninsula distribution

system. The company was not disap-

pointed: revenue in the reduced

territory grew from $251,000 in 1926 to

$277,000 in 1929, and in early 1930 the

company forecast a rosy future for

itself in Ottawa County, projecting

revenue growth to $343,000 in 1933 and

$697,000 in 1937. The depression, of

course, intervened; revenue peaked in

October 1929 and then started to fall,

first slowly and then more rapidly.

Annual sales declined every year through