Ohio History Journal

ROBERT D. MARCUS

James A. Garfield:

Lifting the Mask

The Garfield Orbit: The Life of

President James A. Garfield. By

Margaret

L.eech and Harry J. Brown. (New York:

Harper & Row, 1978. xi +

369p.: illustrations. notes, index. $15.00.)

Garfield. By Allan Peskin. (Kent: Kent State University Press.

1978. x +

716p.: notes, sources listed.

index. $20.00.)

Had Garfield, Arthur, Harrison and Hayes

been young' Or had they all been born

with flowing whiskers, sideburns, and

wing collars, speaking gravely from the

cradle of their mother's arms the noble

vacant sonorities of far-seeing statesman-

ship? It could not be. Had they not all

been young men in the'Thirties. the'Forties,

and the 'Fifties? Did they not, as we.

cry out at night along deserted roads into

demented winds'? Did they not, as we,

cry out in ecstasy and exultancy, as the full

measure of their hunger, their potent

and inchoate hope, went out into that single

wordless cry'?

Along with other political leaders of

the Gilded Age these "Four Lost

Men" of whom Thomas Wolfe writes

have again become the source of a

flourishing historical industry. The men

that Matthew Josephson collec-

tively and disparagingly referred to in

1938 as "The Politicos" are one by

one having their historical reputations

refurbished -perhaps regilded-in

massive and scholarly biographies. Two

new books on James A. Garfield,

Civil War hero, Republican leader in the

House of Representatives, and

briefly President in 1881, are

distinguished contributions to this effort.

"For who was Garfield, martyred

man, and who had seen him in the streets

of life'? Who could believe his

footfalls ever sounded on a lonely pave-

ment'?" One can assure the Wolfean romantic

that James A. Garfield. he of

the "flowing whiskers" and the

"noble vacant sonorities of far-seeing

statesmanship," had indeed cried

out "in ecstasy and exultancy" as a young

Robert D. Marcus is Associate Professor

of History and Dean for Undergraduate Studies

at State University of New York at Stony

Brook.

1. Thomas Wolfe. "The Four lost

Men." From Death to Morning (New York. 1935), 126

|

James A. Garfield 79 |

|

|

|

man. He was real; he was interesting; and in these books we can hear him cry. Allan Peskin's Garfield and Margaret Leech and Harry J. Brown's curiously titled The Garfield Orbit have quite different virtues. Both are works of splendid scholarship, though Peskin's is the traditional full biography destined to be the standard account of the life and public works of the twentieth President. The Garfield Orbit on the other hand is a fragment of Margaret Leech's projected full-scale biography, briefly and rather dryly completed after her death by Harry J. Brown, co-editor of Garfield's diaries. Focusing on Garfield's personal life, particularly his relationships with women, the first six of Leech's eight chapters are a masterful response to Wolfe's-and the twentieth century reader's- demand for a reality behind the bearded Gilded Age image. In sometimes over-rich almost nineteenth century prose ("She quickly freed herself and ran from the cause of such indecorous excitement."), the author penetrates with twentieth century psychological acuity her hero's development and character. Leech's two chapters on the war are inferior to the more complete and interesting account Peskin offers, and Brown's two chapters on Garfield's political career are far too thin to compete in any way with Peskin's detailed, careful and informed narrative. The picture that emerges here does not substantially alter Garfield's |

80 ()O10

HISTORY

historical reputation as a weak,

indecisive man whose career was marred by

a series of allegations against his

character, few of which stuck fast but none

of which quite came off clean. Did

Garfield betray his friend and command-

er General William S. Rosecrans in 1863?

Was he false to John Sherman in

1880? Did he make deals with Roscoe

Conkling and the "stalwarts" in 1880

and break them in 1881? Did he profit

from the Credit Mohilier? In short,

was this president a crook?

In Peskin's well-balanced view Garfield

was never as guilty as his enemies

alleged nor as innocent as he or his

friends protested. In fact, Peskin

unearths several shady deals and

conflicts of interest in addition to those

which were the subject of contemporary

partisan debate. He also abun-

dantly documents Garfield's

indecisiveness and James G. Blaine's remarka-

ble domination over him. Nonetheless

Peskin correctly argues that Gar-

field's ethical standards were normal

for his age and acceptable in the

political culture of his time. His

"vacillation." Peskin thinks, indicated

open-mindedness and discomfort with the

fierce partisanship of late

nineteenth century political life.

Stressing Garfield's voracious reading and

wide-ranging interest, he suggests that

Garfield was an early version of the

intellectual in politics, precursor of a

characteristic twentieth-century type.

In addition, Peskin identifies

Garfield's years of work on the House

Appropriations Committee with the

modernization of the federal bureau-

cracy that Leonard D. White2 has

suggested began to occur in this period.

Garfield had a passion for statistics,

spending long hours on the details of

appropriations bills and investing a

huge amount of time in modernizing

the United States Census.

Although Peskin quite correctly

reevaluates the Garfield "politico"

stereotype. he fails to place the

twentieth president in the context of other

Gilded Age leaders who, like him, built

their political careers around

complicated issues requiring intense

study and expertise, not merely

partisanship. The two other Ohio

Republicans who distinguished them-

selves in national politics, John

Sherman and William McKinley, shared

Garfield's fascination with numbers and

sought in the intricacies of public

finance and tariff schedules a role

elevated above the worn partisan themes

of civil war and reconstruction. Perhaps

such interests do not quite make

one an intellectual in politics (and

neither McKinley nor Sherman had

Garfield's extra-political intellectual

pursuits), but they do suggest a certain

remove and even discomfort with the

political style of the era. Garfield was

an uncomfortable partisan although he

surely was a partisan. Similarly,

Sherman was a wholly uncomfortable

politician, cold and remote, but

nonetheless a politician through and

through: and McKinley, straightfor-

2. Leonard D. White. The Republican

Era, 1869-1901.: A Studl in Administrative History

(New York, 1958).

James A. Garfield 81

ward party man that he was, managed to

project an aura of morality that

men like Mark Hanna worshiped. These men

marked the hard center of the

Republican party, the pivot turning the

party first to the East and then to

the West, now to its wartime roots, now

to its industrial future. The epithet

"politico" is insufficient to

describe these flexible moralists, these above-

the-battle partisans, who became

cultural idols for the party faithful.

Peskin is right to take seriously both

Garfield's party role and his distaste

for partisanship. Both were necessary to

make him the available man in

1880.

Garfield's availability, the fit between

his career and character and the

political needs of the time, is the most

interesting thing about him, far more

significant than his impact on public

policy. Peskin makes a valiant effort

to establish the importance of

Garfield's administration, claiming that "as a

party leader [Garfield], along with

Blaine forged the Republican Party into

the instrument that would lead the

United States into the 20th Century."

This judgment rests primarily on

Garfield's assertion of the power of the

executive against Roscoe Conkling's

claims of senatorial courtesy. Peskin,

I think, exaggerates Garfield's role.

Hayes had hammered away at the

Conkling organization throughout his

administration while Conklin's New

York rivals had eroded his power in the

Empire State. Of Conkling's three

chief henchmen, Chester Arthur violated

his wishes by becoming the vice-

presidential candidate; Thomas C. Platt

had already made agreements with

Conkling's enemies that would have

forced him to betray Conkling had he

not instead resigned from the Senate in

1881; Alonzo B. Cornell early

infuriated Conkling by demanding an

accommodation with the new

administration. In other words, Garfield

triumphed over an already fading

power, and then only after Blaine had

forced him into it. In the history of

the growth of the American presidency,

Garfield's administration merits

but a sentence, and one laden with

qualifiers.

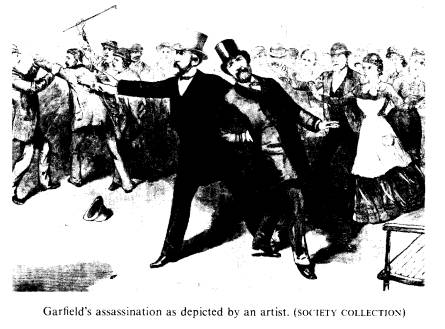

Garfield's life, however, retains an

intrinsic interest. It provided fertile

material for campaign biographies: his

birth in a log cabin, his boyhood on

the Western Reserve, his work on a canal

towpath, his experience in the

Civil War, his ability to defend his

honor against attacks on his morality.

H is death, after an inconclusive few

months as president, produced genuine

national mourning. Even his demented

assassin felt the tug of Garfield's

appeal: "Garfield was a good man,

but a weak politician," was Charles

Guiteau's appraisal. Why was Garfield,

despite his limited achievements, so

appealing to his generation? U

nfortunately Peskin's massively documented

biography lacks the psychological

penetration to tell us. We see something

of the private Garfield, much of the

public one, but nothing to answer

Wolfe's ironic question, to suggest how

the dreams and passions of the

antebellum era-of which Garfield was so

full-led to such a thin con-

clusion in the postwar years.

|

82 1110O HISTORY |

|

|

|

Garfield himself provided many clues. Few nineteenth century Americans left behind such detailed records. Garfield's diaries and correspondence are those of a would-be writer who treasures every scrap of experience in case it will some day be useful for a novel or an essay. Hidden within the politician was a second Garfield. the shadow of a young man such as Thomas Wolfe had envisoned. Behind the lifelong sense of destiny which led him to high office was a perpetual vulnerability that made Garfield see his own life as merely "a series of accidents, mostly of a favorable nature." This duality must have reflected and interpreted his generation's experience for a large audience. The unusually thorough record of his inner as well as his public life should offer clues to the transition from "the young men in the 'Thirties, the 'Forties, and the 'Fifties" to the "gravely vacant and bewhiskered faces" of the Gilded Age. Margaret Leech's account of Garfield's youth does offer some of the insight lacking in Peskin's work, although The Garfield Orbit's incomplete state again frustrates the attempt to grasp the figure whole. Leech subtly captures the young Garfield's sense of boundless destiny that jarred so often with the sense of embarrassment he felt over the poverty and "chaos" (his own word) of his childhood. The torments of the young provincial have rarely been so well described. (In fact, one is reminded strongly of the novels of Thomas Wolfe!) Garfield sees education as the opportunity to |

James A. Garfield 83

"rise above the groveling

herd": his first letter home is headed "First Epistle

of James." Religion is something

between a shield and a weapon. Among

the Campbellite Baptists-he became a

convert at age nineteen-his

sanctity helps compensate for his

poverty. He attributes the "taunts, jeers,

and cold, averted looks" of others

to sectarian bickering.

Religion and education mediate his

initiation into both sex and poli-

tics. He learns to speak, to persuade,

to draw people to him. Religious

exhortation moves him imperceptibly into

antislavery politics so that

Garfield is left with a sense of

superiority over his brethren, not the guilt of

backsliding. Similarly, holy affections

ascend to carnal ones: Thomas

Wolfe would have sighed with relief had

he known of Garfield's elevated

but erotic affair with fellow

Campbellite Rebecca Jane Selleck. The

portrait of Garfield as a platonizing

Baptist rake is a classic piece of

American social history: no one has ever

captured more successfully the

highly developed nineteenth century

American capacity to violate one's

moral code without violating one's

conscience. Leech's account ends before

the reader can realize fully the effect

on Garfield of his Civil War expe-

rience. Secession relieved him of his

religious pacifism. The war itself

seemed to transform his moralism into a

sword. Like so many of his

generation, intense battle experience in

a just cause sharpened his belief in

the ultimate righteousness of his

emotions and ambitions. One of his first

business ventures, even before the war

ended, involved trading on his

reputation as the "hero of the

Sandy Valley" of Tennessee to sell land in his

field of triumph in a way that Peskin

correctly describes as close to an "out-

and-out swindle." Garfield's career

is perhaps a case study in the capacity of

war to produce moral exhaustion-although

one can clearly see the origin

of the older, morally dubious Garfield

in Leech's picture of the lively young

man.

The large heroisms of war made it hard

to respect the small heroisms that

make up daily life. The romantic tone of

the pre-war years faded behind the

masks that puzzled Wolfe. And this

generation, as Ari Hoogenboom has

noted, made the symbolism exact by

sprouting beards at the outset of the

war, literally downing masks. Of course

beards really have nothing to do

with the matter. One reads the memoirs

of bright and vivid young women

like Julia Bundy Foraker and Mary Logan,

and there too one sees a similar

transformation. Eager, ambitious young

women ready to grasp the world

become dowagers attending balls,

dropping names, and remembering who

wore what. Perhaps to understand this

generation we must forget Oliver

Wendell Holmes' excited phrase(which

Peskin quotes) that in the war "our

hearts were touched with fire," and

look ahead to Ernest Hemingway.

Perhaps the "four lost men"

were another earlier lost generation. These two

fine books, particularly the magnificent

early chapters of The Garfield

Orbit, take us part of the way toward finding these lost

Americans.