Ohio History Journal

JON GLASGOW

The Westward Expansion

of the Manufacturing

Belt: The Ohio Machine Tool

Industry in

the Late

Nineteenth Century

For more than sixty years the

Manufacturing Belt has been recog-

nized as an important feature of the

human geography of the United

States. Early studies, mostly by

geographers,1 delimited the current

areal extent of the region-roughly a

quadrilateral with corners at St.

Louis, Minneapolis, Portland (Maine),

and Richmond. Later, attention

shifted from description to explanation

as geographers were joined by

scholars from other disciplines who were

also interested in finding

answers to questions about the

locational aspects of the Manufacturing

Belt.2 Why did it originate

in New England rather than elsewhere?

Jon Glasgow is Associate Professor of

Geography at The College at New Paltz, State

University of New York.

1. Sten DeGeer, "The American

Manufacturing Belt," Georgrafiska Annaler, 9

(1927), 233-359; Richard Hartshore,

"A New Map of the Manufacturing Belt of

North

America," Economic Geography, 12

(1936), 45-53; Clarence Jones, "Areal Distribution

of Manufacturing in the United States, Economic

Geography, 14 (1938), 217-22; Alfred

Wright, "Manufacturing Districts of

the United States," Economic Geography, 14

(1938), 195-200.

2. Robert Aduddell and Louis Cain,

"Location and Collusion in the Meat Packing

Industry," in Business

Enterprise and Economic Change, ed. by Louis Cain and Paul

Uselding (Kent, Ohio, 1973), 85-117;

Fred Bateman and Thomas Weiss, "Comparative

Regional Development in Antebellum

Manufacturing," The Journal of Economic

History, 35 (1975), 182-208; John Borchert, "America's

Changing Metropolitan Re-

gions," Annals of the

Association of American Geographers, 62 (1972), 352-73; Andrew

Burghardt, "A Hypothesis About

Gateway Cities," Annals of the Association of

American Geographers, 61 (1971), 269-85; Edward Duggan, "Machines,

Markets, and

Labor: The Carriage and Wagon Industry

in Late-Nineteenth Century Cincinnati,"

Business History Review, 51 (1977), 308-25; Irwin Feller, "The Diffusion

and Location

of Technological Change in the American

Cotton-Textile Industry, 1890-1970," Tech-

nology and Culture, 15 (1974), 569-93; Jean Gottman, Megalopolis: The

Urbanized

Northeastern Seaboard of the United

States (Cambridge, Mass., 1961); David

Meyer,

20 OHIO

HISTORY

Why it expanded westward as far as St.

Louis and Minneapolis but no

further? Why did it become internally

differentiated with particular

cities specializing in the manufacture

of some products rather than

other ones? With the decline of the

dominance of the Manufacturing

Belt, recent works have offered

prescriptions for retaining existing

industries and for attracting new ones,

or policies to ameliorate the ill

effects of industrial decline.3 However,

the task of explanation is not

complete; for some important events

involved in the extension of the

Manufacturing Belt across the

Appalachians into the Midwest remain

to be explained. One such event is the

emergence, between 1880 and

1900, of a trans-Appalachian machine

tool industry centered in Ohio

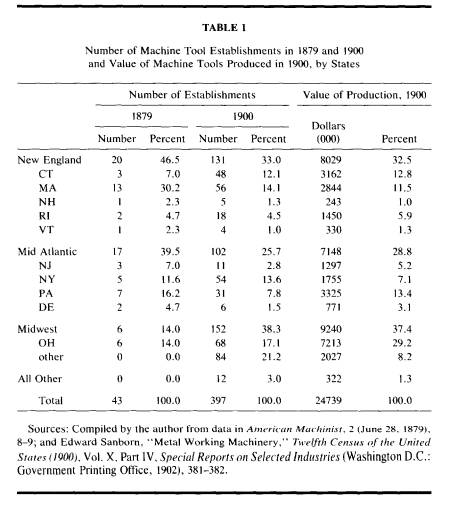

(Table 1). This coincided with the first

appearance of firms that

specialized in the production of machine

tools and with advances in

machine tool technology that were

prerequisities for the later develop-

ment of assembly line production of

automobiles.4 Without the pres-

ence of nearby and innovative machine

tool producers, it would have

been difficult for turn-of-the-century

automobile firms of the Midwest

to challenge those of New England for

supremacy in the national

market, and the subsequent geographical

evolution of the Manufactur-

ing Belt might have been very different.

The premise of this paper is that the

development of machine tool

production in Ohio was a manifestation

of the Industrial Frontier

Hypothesis. In a previous study of the

time and place of origin of three

manufacturing industries,5 it

was shown that in each case: (1) crucial

financial backing had been provided by local

entrepreneurs who

"Emergence of the American

Manufacturing Belt: An Interpretation," Journal of

Historical Geography, 9 (1983), 145-74; Allan Pred, The Spatial Dynamics of

U.S.

Urban Industrial Growth, 1800-1914;

Interpretive and Theoretical Essays (Cambridge,

Mass., 1966): Mary Beth Pudup,

"From Farm to Factory: Structuring and Location of

the U.S. Farm Machinery Industry," Ecomonic

Geography, 63 (1987), 203-22; David

Ward, Cities and Immigrants: A

Geography of Change in Nineteeth Century America

(New York, 1971).

3. Barry Bluestone and Bennett Harrison,

The Deindustrialization of America (New

York, 1982); Ann Markusen, Regions:

The Economics and Polities of Territory (Totowa,

NJ, 1987): Richard Peet, "Relations

of Production and the Relocation of United States

Manufacturing Industry Since 1960,"

Economic Geography, 59 (1983), 11243; Neil

Smith and Ward Dennis, "The

Restructuring of Geographical Scale: Coalescence and

Fragmentation of the Northern Core

Region," Economic Geography, 63 (1987), 160-82.

4. Victor S. Clark, History of

Manufactures in the United States. Vol. IlI,

1893-1928 (New York, 1929), 153; Frederick Geier, The Coming

of the Machine Tool

Age: The Tool Builders of Cincinnati (New York, 1949), 11; Joseph Roe, English and

American Tool Builders (New Haven, 1916), 261; Nathan Rosenberg,

"Technological

Change in the Machine Tool Industry,

1840-1910," The Journal of Economic History, 23

(1963), 414-43.

5. Jon Glasgow, "Innovation on the

Frontier of the American Manufacturing Belt,"

Pennsylvania History, 52 (1985), 1-21.

|

Westward Expansion of the Manufacturing Belt 21 |

|

|

|

needed new investment opportunities to maintain the small fortunes that they had made in frontier extractive industries that were threat- ened by resource depletion; and (2) that essential technical expertise had been contributed by migrants to the newly industrializing centers from older eastern centers. These previously studied innovations on the Industrial Frontier were the anthracite-fueled iron industry of Bethlehem (Pennsylvania) in the 1840s, the Bessemer process steel industry in Pittsburgh in the 1870s, and the assembly line production of automobiles in Detroit in the 1910s. The emergence between 1880 and 1900 of the machine tool industry in Ohio fits into this historical- |

22 OHIO HISTORY

geographical sequence and is, therefore,

consistent with the idea of a

westward moving Industrial Frontier

within which conditions were

especially favorable for industrial

innovation. Two other pertinent

concepts are David Meyer's idea of

"Replicated Systems"6 to under-

stand the development of

trans-Appalachian manufacturing in general,

and George Wing's "Steamboat

Theory"7 to explain the development

of machine tool production in Cincinnati

in particular. Wing maintains

that skilled labor was critical in

explaining the growth of the machine

tool industry, and that Cincinnati had a

surplus of skilled machinists in

the 1890s because the recent decline of

the local steamboat manufac-

turing industry meant that "...

individuals who had received their

training in the old industry had to seek

other avenues for their

talents."8 This

interpretation is plausible for Cincinnati, but it does not

explain why the other major

trans-Appalachian centers of steamboat

production-Pittsburgh, Louisville, and

St. Louis-did not develop

into rival centers of machine tool

production.

According to Meyer, the major industrial

cities of the Midwest

originated as producers of manufactured

products for relatively self-

sufficient market regions which he

called "replicated systems."9 All

such regions had similar demands for

manufactured products; there-

fore, each nascent regional center had

about the same mix of manu-

facturing industries, including

producers of machine tools. Differences

in industrial structure among these

cities began to develop in the 1850s

and 1860s as individual firms in

particular cities took advantage of

declining freight rates and increasing

scale economies in production to

capture multi-regional and even national

markets.

Each industrial system [i.e. market

region] was a potential location for a new

industry. Its location depended on ties

to existing multiregional/national

industries that conveyed advantages to

some industrial systems and on a

random location of inventors and

innovators ... .10

The Wing and Meyer interpretations have

interesting parallels with

and differences from the Industrial

Frontier Hypothesis. As in the

Industrial Frontier Hypothesis, Wing

proposes that the decline of an

established industry, by releasing

resources that are not readily avail-

6. Meyer, "American Manufacturing

Belt."

7. George Wing, "The History of the

Cincinnati Machine-Tool Industry," (unpub-

lished D.B.A. dissertation, Indiana

University, 1964).

8. Ibid., 44, 59-60. See also Clark, Manufactures

in the United States, Vol. II, 360;

and Roe, Tool Builders, 266-67.

9. Meyer, "American Manufacturing

Belt."

10. Ibid.. 161.

Westward Expansion of the

Manufacturing Belt

23

able elsewhere, can provide an advantage

for attracting new industries

to a region. A significant difference is

that Wing specified skilled labor

released from the demise of an obsolete

manufacturing industry rather

than capital and entrepreneurship driven

out of primary industries by

the depletion of natural resources.

Although Meyer's interpretation

and that of the Industrial Frontier both

recognize the importance of the

location of invention and innovation in

explaining the location of

manufacturing industry, Meyer describes

innovators and inventors as

having been randomly distributed among

places. Contrarily, the idea of

an Industrial Frontier connotes that

innovators and inventors, along

with skilled laborers and entrepreneurs,

migrated to the Industrial

Frontier in sufficient numbers to create

a region that was especially

conducive to the creation of new

manufacturing industries.

Combining the ideas of Meyer and Wing

with that of the Industrial

Frontier provides the following

plausible, but as yet unsubstantiated,

explanation for the emergence of the

Ohio machine tool industry. The

first machine tools produced in the

United States were made as a

sideline by Philadelphia and New England

firms that needed machine

tools themselves to manufacture products

such a textile machinery,

firearms, and locomotives. Some of the

more innovative of these firms

capitalized on the expanding market for

their sideline by shifting to

machine tools as their major

product." As demand for manufactured

products increased in the

trans-Appalachian west, Meyer's "replicated

systems" emerged including firms

that would evolve into machine tool

producers by the same process. Then,

just as critical advances were

being made in machine tool technology,

conditions conducive to

industrial innovation spread westward

with the Industrial Frontier into

Ohio, accounting for its rise to first

place in machine tool production.

Following Wing's idea, Cincinnati became

the leading city in machine

tool production, surpassing rival Ohio

industrial center Cleveland,

because of the special advantage of

skilled labor released by the

cessation of steamboat production in

Cincinnati.

11. Thomas Cochran, Frontiers of

Change: Early Industrialization in America (New

York, 1981), 61; George Gibb, The

Sacco-Lowell Shops: Textile Machinery Building in

New England 1813-1944 (New York, 1969), 179; Guy Hubbard, "The Machine

Tool

Industry," in The Development of

American Industries: Their Economic Significance ed.

by John Glover and William Bouck (New

York, 1933), 510-19; Roe, English and

American Tool Builders, 114-20; Nathan Rosenberg, Technology and American

Eco-

nomic Growth (New York, 1972), 99; Merritt Smith, "John Hall,

Simeon North, and the

Milling Machine: The Nature of

Innovation among Antebellum Arms Makers," Tech-

nology and Culture, 14 (1973), 573-91; W. Paul Strassman, Risk and

Technological

Innovation: American Manufacturing

Methods during the Nineteenth Century (Ithaca,

N.Y., 1959), 117-30; Robert Woodbury, Studies

in the History of Machine Tools

(Cambridge, Mass., 1972).

24 OHIO HISTORY

Perhaps the most conjectural part of the

above explanation is the

assertion that, as early as 1880,

conditions in Ohio were unusually

favorable for the establishment of firms

specializing in the production

of machine tools for national markets.

This study provides evidence

that such favorable conditions did

exist, as indicated by the concen-

tration in Ohio of what are hereafter

referred to as Precursor Indus-

tries-industries presumed to have been

strongly linked to machine

tool production and which provided the

preconditions for the develop-

ment of a machine tool industry with a

national market.

Eighteen-eighty has been selected as the

appropriate year for this

study, for the following reasons.

Consistent with the idea of an

Industrial Frontier, 1880 has been

identified as the year in which

Skilled mechanics in the workshops of

New England and Philadelphia ...

began to cross the Alleghenies in

increasing numbers. Settling in ... Cincin-

nati, Cleveland, and Hamilton [a

satellite of Cincinnati] they prospered so well

that Cincinnati . . . ultimately ousted

Philadelphia to become the machine-tool

making capital of America.12

Furthermore, 1880 has been described as

".. a significant bench-

mark ... in terms of technical

innovation leading to mass production

...;"13 the year in which " ... a group of firms whose

principle product

was machine tools ..." first

appeared;14 and as the initial year in a

three-decade era "... characterized

by an immense increase in the

,,15

development of machine tools for highly

specialized purposes ...."15

From the 332 industries for which data

are published in the 1880

Census of Manufacturing,16 twenty-two

were identified as being pre-

cursors of the machine tool industry.

Nine of these were described in

Fitch's seminal 1880 census monograph17

as being either industries that

required automatic or precision metal

working, or used interchange-

able parts: agricultural implements,

ammunition, clocks, cutlery and

edge tools, firearms, hardware, railroad

and street cars, sewing ma-

chines, and watches. Seven industries

were added because of their

apparent similarity to, or relationship

with, the first nine: watch cases,

12. Lionell Rolt, A Short History of

Machine Tools (Cambridge, Mass., 1965), 176.

13. John James, "Structural Change

in American Manufacturing, 1850-1890," The

Journal of Economic History, 43 (1983), 440.

14. Ross Robertson, Changing

Production of Metalworking Machinery: 1860-1920,

Studies in Income and Wealth, Vol. 30

(New York, 1966), 484.

15. Rosenberg, "Technological

Change," 433.

16. Department of the Interior (Census

Office), Report on the Manufactures of the

United States at the Tenth Census:

(June 1, 1880): General Statistics (Washington

D.C.,

1883), "Table II: The United States

by Specified Industries," 19-24.

17. Charles Fitch, "Report on the

Manufactures of Interchangeable Mechanism," in

Department of the Interior, Manufactures

of the United States, 1880.

|

Westward Expansion of the Manufacturing Belt 25 |

|

|

|

clock cases, watch and clock materials, files, saws, screws, and tools. Six additional industries were included for the following reasons: the carriage and wagon industry and the carriage and wagon materials industry because the former has been proposed as being one of the first industries in which power machinery was efficiently used to manufac- ture a complex product;18 the models and patterns industry because it supplied a vital service to machine tool producers; the professional and scientific instruments industry as one that required precise machining of metal parts; the foundry and machine shop industry because it included the few firms that specialized in machine tool production in

18. Duggan, "Machines, Markets, and Labor," 309. |

26 OHIO

HISTORY

1880; and the foundry supply industry

for its presumed connection to

the foundry and machine shop industry.

Data pertaining to nineteen Precursor

Industries19 were compiled for

Cincinnati, Cleveland and ten other

cities20 selected to create three

groups of four cities each (Table 2).

The Northeast group consists of

the four cities that ranked second

through fifth, after Cincinnati, in

machine tool production in 1900.21

Cincinnati and the three other major

trans-Appalachian centers of steamboat

production constitute the

group of River Cities.22 The

Lake Cities include Cleveland and the

three other cities on the Great Lakes

that had, in 1880, numbers of

manufacturing employees most similar to

the number employed in

Cleveland.23

It is reasonable to assume that the most

favorable conditions for the

development of machine tool production

were in those cities with labor

forces possessing the greatest variety

of skills and expertise in Precur-

sor Industries as measured, initially,

by the total number of Precursor

Industries found in a city (Table 2,

column 1). Note that by this

measure Cincinnati and Cleveland each

rank first in their respective

groups and that their numbers are within

the range of the cities of the

Northeast group. Since a Precursor

Industry in a city may have

consisted of only one small and

inefficient firm with a market limited to

that city, the numbers listed in column

1 of Table 2 may be misleading.

Therefore, an attempt was made to

identify cities in which Precursor

Industries served larger than local

markets and cities in which Precur-

sor Industries were unusually

productive. In a city in which a Precur-

sor Industry's percentage of the local

manufacturing labor force

exceeded that industry's percentage of

the national labor force (i.e.,

cities in which the location quotient24

for that industry exceeded 1.0),

19. Three of the twenty-two Precursor

Industries (ammunition, clock cases, and

watches) were not found in any of the

cities examined in this study.

20. Although the more familiar city

names are used throughout this study, the data are

for the counties in which the cities are

located. County data were preferred to city data

(both were available in the 1880 Census

of Manufacturing) so that factories located just

beyond the corporate limits of cities

would be included in the study.

21. Edward Sanborn, "Metal-Working

Machinery," in U.S. Census of Manufactur-

ing 1900, Vol. X., Part IV, Special Reports on Selected

Industries (Washington, D.C.,

1902), 385.

22. Louis Hunter, Steamboats on the

Western Rivers: An Economic and Technolog-

ical History (New York, 1969) 105-07.

23. Francis Walker, "Remarks on the

Statistics of Manufactures," in Department of

the Interior, Manufactures of the

United States, 1880: General Statistics, xxiv-xxv. The

appropriate data are Cleveland 21,724;

Milwaukee 20,886; Buffalo 18,021; and Detroit

16,110.

24. The location quotient is a commonly

used measure of the extent to which

phenomena are concentrated in particular

places. See, for example, George Schnell and

|

Westward Expansion of the Manufacturing Belt 27 |

|

|

|

that industry was presumed to have a market that extended beyond the city. Such industries are listed as Extensive Market Precursor Indus- tries in the second column of Table 2. As in the first column of Table 2, Cincinnati and Cleveland rank first in their group and have numbers that are comparable to the cities of the Northeast. A city in which the value added per employee in a Precursor Industry exceeded the national average in the industry was deemed to have a More Productive Precursor Industry (Table 2, column 3),25 ostensibly the result of that city having more tractable or more highly skilled labor, or of firms in that city having introduced more highly mechanized processes. The

Mark Monmonier, The Study of Population: Elements, Patterns and Processes (Colum- bus, 1983), 28-29. 25. Value added was computed by subtracting the "Value of materials" from the "Value of products" listed in "Table V-Selected Statistics of Manufactures by Counties, 1880," in Department of the Interior, Manufactures of the United States, 1880. |

28 OHIO HISTORY

numbers in the third column of Table 2

do not follow the pattern that

appears in the first two columns.

However, it is worth noting that Cin-

cinnati ranks first in this column, and

a close second in the other two.

In general, the data arrayed in Table 2

show that Cincinnati and

Cleveland had numbers of Precursor

Industries comparable to the

major machine tool centers of the

Northeast, and distinctly higher

numbers than the other cities in the

"River" and "Lake" Groups. The

validity of this generalization becomes

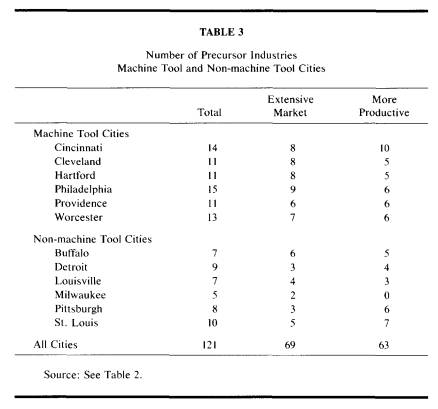

more apparent by examining

Table 3 in which Cincinnati and

Cleveland have been merged with the

Northeast to form a group of six Machine

Tool Cities, leaving the

remaining three River Cities and three

Lake Cities to be combined into

a group of six Non-machine Tool Cities.

Note that this regrouping of

cities precisely discriminates between

cities with higher and lower

numbers of Total Precursor Industries

(Table 3, column 1), and misses

by only one city (Buffalo) in

discriminating between cities with higher

and lower numbers of Extensive Market

Precursor Industries (Table 3,

column 2). Except for Cincinnati,

however, the Machine Tool Cities do

not appear to be significantly different

from the Non-machine Tool

Cities in numbers of More Productive

Precursor Industries (Table 3,

column 3). This somewhat unexpected

outcome with respect to the

More Productive Precursor Industries led

to the following refinement

in classifying Precursor Industries

(Table 4).

Table 4 shows the Precursor Industries

arranged in descending order

by the number of sample cities in which

each occurred in 1880. Since

they were found with equal frequency in

Machine Tool and Non-

machine Tool Cities, the first eight

industries are called General Pre-

cursor Industries. The other eleven

industries, each found in less than

half of the sampled cities, are located almost

exclusively in Machine

Tool cities. Evidently, these eleven

Specialized Precursor Industries

had demanding labor, technology or

market requirements that were

found in only a limited number of

manufacturing centers in 1880.

Machine Tool and Non-machine Tool cities

are nearly identical with

respect to numbers of General Precursor

Industries (Table 5). In the

aggregate, each group has exactly the

same total number (41), very

nearly the same number with Extensive

Markets (18 and 21), and very

nearly the same number of More

Productive ones (24 and 21).

Likewise, examining the numbers of

General Precursor Industries

listed for individual cities in Table 5

reveals only slight differences

between the two groups of cities. The

total numbers range from 5 to 8

for Machine Tool cities and from 4 to 8

for Non-machine Tool cities;

the number with extensive markets range

from 2 to 4 and from I to 6

respectively; and the number of More

Productive, General Precursor

Industries ranges from 1 to 7 for

Machine Tool Cities and from 0 to 5

|

Westward Expansion of the Manufacturing Belt 29 |

|

|

|

for Non-machine Tool Cities. Evidently, the presence of these General Precursor Industries did not assure that a city would develop into a major center of machine tool production. In contrast, the Specialized Precursor Industry section of Table 5 displays unequivocable differences between the two groups of cities with totals ranging from 4 to 6 among the Machine Tool cities and from 0 to 2 among the Non-machine Tool cities (Table 5, column 4). The clearest distinction between Machine Tool and Non-machine Tool cities-and the most convincing evidence in support of the premise of this study-is found in the fifth column of Table 5: Specialized Precursor Industries with Extensive Markets were almost nonexistent |

|

30 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

in the Non-machine Tool group of cities, one each in St. Louis and Milwaukee and none in the other four, while every one of the Machine Tool cities had a least four of these industries. These data offer the sought for evidence that preconditions for the development of firms producing special purpose machine tools for the national market had, by 1880, extended across the Appalachians to Cincinnati and Cleve- land, but not to other River and Lake cities. Before concluding, however, some further comments about the More Productive Precur- sor Industries are in order. As can be seen from comparing the third and sixth columns of Table 5, separating Specialized from General Precursor Industries enhances the contrast between Machine Tool and Non-machine Tool cities with respect to number of More Productive Precursor Industries. Fourteen |

|

Westward Expansion of the Manufacturing Belt 31 |

|

|

|

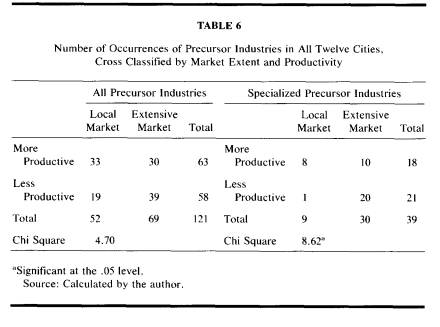

of eighteen Specialized, More Productive industries were in Machine Tool cities, whereas the number of General, More Productive indus- tries is almost evenly divided between the two groups of cities (24 and 21). Nevertheless, the More Productive Precursor Industries still pose some interesting problems. For example, a higher proportion of General Precursor Industries than Specialized Precursor Industries were identified as being More Productive (45 of 82 compared to 18 of 39). Furthermore (Table 6), nearly two-thirds (33 of 52) of the Local Market industries were in the More Productive category, yet fewer than half (30 of 69) of the Extensive Market Precursor Industries were identified as More Productive. This apparently negative relationship between productivity and extent of market becomes stronger when the comparison is limited to the Specialized Precursor Industries: 10 of 30 Extensive Market compared to 8 of 9 Local Market classified as More Productive. Indications that General Precursor Industries were more productive than Specialized ones and that Precursor Industries in the Non-machine Tool cities were more productive than those in the Machine Tool cities are unexpected. It could be that Specialized Precursor Industries in Machine Tool cities consisted of unusually large proportions of very young firms that had just begun to develop from small, labor intensive, local market firms with low ratios of value |

|

32 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

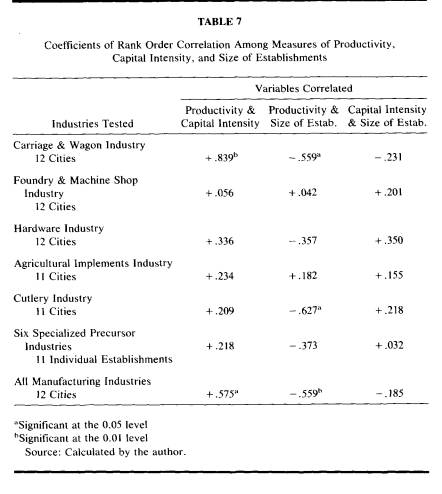

added per worker hour into firms that were larger and more capital intensive, with more extensive markets and more productive labor forces. This notion cannot be verified within the scope of the present paper, but Table 7 does report the result of some tests of rank-order correlations among measures of labor productivity (value added per employee), capital intensity (capital invested per employee), and size of establishment (number of employees per establishment). The first five tests use data from the five Precursor Industries that were found in at least eleven of the sampled cities. Of necessity, all of these are General Precursor Industries. In order to include analysis of Special- |

Westward Expansion of the

Manufacturing Belt 33

ized Precursor Industries, none of which

occurred in enough cities to

permit valid rank-order correlation of

within-industry relationships, the

sixth test used data for eleven

individual firms distributed among six

separate Specialized Precursor

Industries in seven different cities-the

six Machine Tool cities plus Milwaukee.

These are the eleven cases in

which a specialized Precursor Industry

was represented in a city by a

single establishment.26 The

seventh test includes data from all twelve

of the sample cities for all

manufacturing industry in the aggregate, not

limited to Precursor Industries. As

expected, all coefficients between

value added per employee and capital

intensity were positive, although

only two of these were significant at

the 0.05 level. Surprisingly, five of

the seven correlations between

productivity and size of establishment

were negative, with three of the

negative correlations significant at the

0.05 level. None of the correlations

between capital intensity and

establishment size were statistically

significant, but five of the seven

coefficients had the expected positive

sign. Of course, the positive

correlations between productivity and

capital intensity, using these

cross sectional data, cannot be

interpreted as verifying the idea that

increases in capital intensity over time

caused increases in productiv-

ity; however, they do suggest that it

would be worthwhile to acquire the

necessary longitudinal data. Likewise,

negative correlations between

size of establishment and productivity

need not be interpreted as

evidence that as establishments

increased their labor productivity they

reduced the size of their labor forces.

Perhaps 1880 was a year in which

the most productive establishments in

these industries had the fewest

employees because they were the newest

establishments, with their

higher productivity based upon a greater

willingness of such newer

establishments to accept the risks

involved in being innovative.

It is obvious that more needs to be done

to provide conclusive

answers to the questions raised.

Nevertheless, it is hoped that some

progress has been made in understanding

the process by which the

Manufacturing Belt was extended across

the Appalachians into the

Midwest. Specifically, a set of

industries has been identified as being

ones that provided preconditions for the

development of a national

market machine tool industry in a city.

Furthermore, consistent with

the idea of a westward moving frontier

of optimum conditions for

industrial innovation, evidence has been

provided that, in 1880,

Precursor Industries were not randomly

or uniformly distributed

among trans-Appalachian cities; rather

they were concentrated in

26. The disclosure rule forbidding the

publication of data for individual firms was not

in effect in the 1880 Census of

Manufacturing.

34 OHIO HISTORY

Cincinnati and Cleveland-historically

and geographically between the

innovation of mass produced steel, by

the Bessemer process in

Pittsburgh in the 1870s, and the

innovation of mass produced automo-

biles on assembly lines in Detroit in

the 1900 to 1910 decade.