Ohio History Journal

JACK S. BLOCKER JR.

Market Integration, Urban Growth

and Economic Change in an Ohio

County, 1850-1880

In March 1870, the editor of a local

newspaper in Washington

Court House, county seat of Fayette

County, Ohio, announced the

inauguration of a new service by the

Cincinnati and Muskingum

Valley Railroad:

The Train which leaves this place at

6.16 in the morning, arrives in the city

at 10.5, and leaves Cincinnati at 3:50

p.m., thus affording our citizens some

FIVE HOURS for business or pleasure. It

is a real accomodation, and we

hope it will be appreciated by the

public along the line and continued. By

this arrangement, Washington is rendered

almost one of the wards of Cin-

cinnati, and when the weather becomes a

little more pleasant, we expect

this morning Train will be extensively

patronized, and we are afraid to the

injury of our local business.1

The mingled eagerness and anxiety

expressed by this editor have

provided durable themes for commentators

on small-town life in the

nineteenth century. Beyond such

impressions, however, we know

little about the possibly complex

effects when small towns become

integrated into urban systems.2 Studies

of regional and national

systems have been unable to follow the

internal development of all

Jack S. Blocker Jr. is Associate

Professor of History at Huron College, London,

Ontario, Canada. Research and analysis

were supported by a research grant from the

Social Sciences and Humanities Research

Council of Canada. The author wishes to

thank George N. Emery and Dianne C.

Newell for their comments on an earlier

version of this paper.

1. Ohio State Register, March 31, 1870.

2. It is of course virtually inconceivable

that any community in nineteenth-

century America would not be part of an

urban system (although historians of com-

munities sometimes forget this fact).

The term "integration" is used in this essay to

denote movement along an ideal spectrum whose poles are

isolation and incorpora-

tion.

Market Integration

299

but the largest cities.3 At

the same time community microstudies

too rarely have been designed to relate

the internal changes they

describe to shifts in their communities'

external relationships.4 This

paper seeks to employ both external and

internal perspectives to

understand economic change within a

small urban community dur-

ing the process of integration.

Edward K. Muller has described the

shifts in urban relationships

in the middle Ohio Valley during the

period 1800-1860 as a three-

stage process of increasing integration.

In the pioneer period (1800-

1830) urban growth depended upon control

over a growing local

hinterland. Both hinterland growth and

achievement of control de-

pended in turn upon location with

respect to the region's principal

transportation routes, primarily the

Ohio River and its main tribu-

taries. In the second stage (1830-1850)

development of the regional

transportation network through

construction of canals and early

railroad lines stimulated rural

settlement and encouraged special-

ized staple production. Staple

production in turn led to the growth of

processing industries in towns located

on a canal or railroad line.

Cities such as Cincinnati, Dayton and

Columbus, which enjoyed

both access to a large, growing

hinterland and good connections to

national markets, experienced

significant growth based upon a di-

versifying manufacturing sector. This

shift in the basis for urban

growth toward nonprocessing industries

became more evident dur-

3. David Ward, Cities and Immigrants:

A Geography of Change in Nineteenth

Century America (New York, 1971); Edward K. Muller, "Selective

Urban Growth in

the Middle Ohio Valley, 1800-1860,"

Geographical Review, 66 (1976), 178-99; John B.

Sharpless, City Growth in the United

States, England and Wales, 1820-1861: The

Effects of Location, Size and Economic Structure on

Inter-Urban Variations in Dem-

ographic Growth (New York, 1977).

4. Gordon W. Kirk, Jr., The Promise

of American Life: Social Mobility in a

Nineteenth-Century Immigrant Community, Holland,

Michigan, 1847-1894 (Phil-

adelphia, 1978), shows transportation

improvements producing industrialization and

urban growth. Stuart Blumin, The

Urban Threshold: Growth and Change in a

Nineteenth-Century American Community

(Chicago and London, 1976), and Clyde

and Sally Griffen, Natives and

Newcomers: The Ordering of Opportunity in Mid-

Nineteenth-Century Poughkeepsie (Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1978), describe

Hudson River towns dependent upon

national markets since well before the begin-

ning of their study periods. Robert

Doherty, Society and Power: Five New England

Towns, 1800-1860 (Amherst, Mass., 1977), demonstrates ordering of

opportunity

according to an urban hierarchy, but

studies in detail change over only a single

decade, 1850-1860. Anthony F. C.

Wallace, Rockdale: The Growth of an American

Village in the Early Industrial

Revolution (New York, 1978), Don

Harrison Doyle,

The Social Order of a Frontier

Community: Jacksonville, Illinois, 1825-70 (Urbana,

Ill., 1978), and Robert J. Mitchell,

"Tradition and Change in Rural New England: A

Case Study of Brooksville, Maine,

1850-1870," Maine Historical Society Quarterly. 18

(Fall, 1978), 87-105, do not address the

question of integration.

300 OHIO HISTORY

ing the third stage, the 1850s, when

construction of the rail network

was pushed forward rapidly.

Transportation improvements pro-

duced an "upward shift of...

manufacturing functions in the urban

hierarchy" by reducing transport

costs for both agricultural pro-

ducts and manufactured goods. By 1860

the middle Ohio Valley had

become well integrated with national

markets; interregional and

intraregional integration had produced

relatively rapid growth for

those centers possessing the best

connections within the transporta-

tion network, and in such centers growth

was increasingly based

upon secondary manfactures.5

Washington Court House and its

hinterland during the years

1850-1880 furnish a laboratory within

which this process of integra-

tion may be examined in detail.6 Founded

in 1811, by 1850

Washington Court House was a small

district trade center, isolated

by its location off Ohio's canal and

early railroad lines. The building

of a railroad line between Washington

Court House and Cincinnati

in the early 1850s marked a new stage in

the town's integration into

regional and national markets, and the

ensuing quarter-century,

accessible through manuscript and

published federal census data,

provides a long enough period to assess

the principal effects of the

connection. Fayette County will be used

as an approximation of the

hinterland for Washington Court House.7

The questions to be asked concern the

effects of the railroad as an

instrument of integration into a larger

market system. The timing

of those effects is also of interest. As

an isolated local trade center

achieving interregional connections

relatively late, did Washington

Court House experience rapid or slow

growth, or decline? What

demographic and economic changes took

place in its agricultural

hinterland? What structural changes in

the community's economic

5. Muller, "Selective Urban

Growth." See also Margaret Walsh, "The Dynamics of

Industrial Growth in the Old Northwest

1830-70: An Interdisciplinary Approach," in

Business and Economic History: Papers Presented at the

Twenty-first Annual Meeting

of the Business History Conference, ed. Paul Uselding (Urbana, Ill., 1975), 12-29.

Secondary, or nonprocessing,

manufactures finish the product of another factory;

examples are hardwares, railroad cars,

clothing, farm implements, and machinery.

Primary, or processing, industries

operate on the products of agriculture, mining or

forestry. Examples include milling,

distilling and meatpacking.

6. Washington Court House is one of the

towns whose growth was examined by

Muller in "Selective Urban

Growth."

7. Fayette County contained no competing

centers: in 1880, when Washington

Court House had a population of 3,798,

the next largest community, Bloomingburg,

contained only 526 persons. Washington

Court House's hinterland was probably no

larger than Fayette County, as the county

was surrounded by six places of the same

or larger size than Washington Court

House, all within a 30-mile radius of the latter.

|

Market Integration 301 |

|

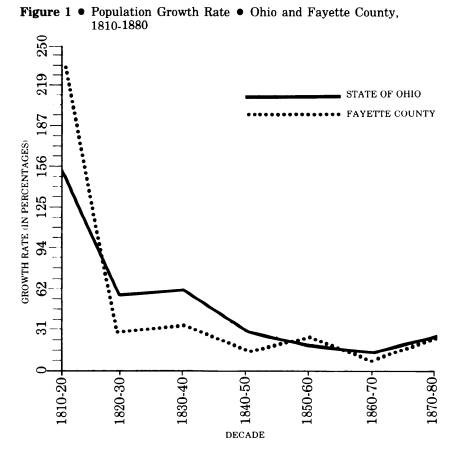

base were produced by integration, and how were they related to demographic shifts? Fayette had never ranked among Ohio's more populous counties. Settled during the first years of the century, until the coming of the railroad it had exceeded the statewide rate of population growth only once, during its pioneer decade (Figure 1). In 1850 Fayette stood 66th in population among the state's 87 counties. Farming was the principal activity of most of its citizens. Some livestock and livestock products were sold outside the county, but further develop- ment of commercial agriculture was restricted because of the diffi- culty of access to regional markets. In 1850, two turnpikes provided the best routes to market, one to Circleville on the Ohio Canal, 30 miles east of Washington Court House, the other to Xenia on the |

302 OHIO HISTORY

Little Miami Railroad, 30 miles

northwest. This meant a journey of

at least three days from the center of

the county simply to bring a

farmer's hogs or sheep to a railroad or

canal line, although corn and

wool could be moved somewhat more

rapidly. Thus, although the

county in 1850 ranked fifteenth in

bushels of Indian corn raised and

twenty-second in number of swine, it

stood thirty-first in value of

livestock and forty-first in cash value

of farms.8 Manufactures were

locally oriented and small in scale:

Fayette ranked seventy-fifth in

value of manufactured products and

seventy-seventh in capital in-

vested in manufacturing.9

The Cincinnati and Muskingum Valley

Railroad arrived at

Washington Court House in 1853,

providing Fayette County a

direct line to the Ohio River

metropolis. The county fathers capital-

ized on the opportunity for marketing

Fayette's farm products by

constructing a network of turnpikes so

extensive that by 1870 the

county ranked fifth in the state in

length of roads.10 Although the

distance as the crow flies from

Washington Court House to Col-

umbus is about half that to Cincinnati,

the railroad placed Fayette

County firmly within the orbit of the

larger city. By 1870 Cincinnati

and Muskingum Valley trains made a

scheduled daily stop each

way for passengers and another for

freight, as well as unscheduled

freight stops. The trip to Cincinnati

took about four-and-one-half

hours. In contrast, Washingtonians

travelling to Columbus relied

upon a thrice-weekly stagecoach which

took seven hours to travel

the shorter distance, returning on the

following day.11

The railroad achieved its most dramatic

effect in stimulating

Fayette County's agricultural sector.

Direct connection with the

pork-packing center of the Midwest and,

through Cincinnati, with

the national pork market encouraged

Fayette's farmers to extend

and intensify their cultivation of corn

and production of hogs.12

Cattle and sheep raising declined as

farmers shifted resources into

corn and hogs. By 1860 the county had

risen to eighth place among

8. Muller, "Selective Urban

Growth," 186; Map of Ohio, Williams' Ohio State Reg-

ister and Business Mirror for 1857 (Cincinnati, 1857); J. D. B. DeBow, Seventh Cen-

sus, . .. 1850 (Washington, D. C., 1853),862-64.

9. J. D. B. DeBow, A Statistical View

of the United States (Washington, D. C.,

1854), 295.

10. Annual Report of the Secretary of

State of Ohio, 1870, 267-73.

11. Ohio State Register, March

24, 31, May 26, 1870.

12. Margaret Walsh has pointed out the

dependence of the pork industry in the

mid-nineteenth century upon the national

market. See "Pork Packing as a Leading

Edge of Midwestern Industry,

1835-1875," Agricultural History, 51 (October 1977),

715.

Market Integration

303

Ohio's now 88 counties in bushels of

corn produced, and by 1870 to

third. In 1860 only ten counties raised

more swine than Fayette, in

1870 only two, and only a single county

reported a higher value for

animals slaughtered or sold for

slaughter. By 1870 Fayette County

had risen to seventh place in value of

livestock, twenty-second in

cash value of farms, and third in value

of all farm products.l3 In

1880 Fayette County still ranked among

the top corn and hog pro-

ducing counties of Ohio, although the

value of its products had

declined both absolutely and relatively

as a result of the lengthy

depression of the 1870s, which seems to

have affected pork prices

more severely than those of other farm

products.14

Clearly the increased integration into a

regional marketing net-

work produced by the railroad stimulated

staple production in

Fayette County. It also encouraged

population growth, as both the

county as a whole (Figure 1) and its

rural areas saw population

increase faster than the statewide

average. Rural population

growth in Fayette County did not however

imply extensive settle-

ment of new farms upon unoccupied land,

for in 1850 84 percent of

the total farmland of 1880 was already

included in existing farms.15

More land was put into production, but

most of it was simply por-

tions of existing farms that had been

left uncleared or uncultivated

because of restricted market

opportunities.16 Rural population

13. Joseph C. G. Kennedy, Agriculture

of the United States, 1860 (Washington,

D.C., 1864), 112-19; Ninth Census, vol.

3, Statistics of Wealth and Industry (Washing-

ton, D. C., 1872), 222-29. Value of farm products was

not reported in 1850 or 1860; in

those years the census also reported only the value of

animals slaughtered in each

county rather than the more inclusive category of 1870.

14. Report on the Productions of Agriculture As

Returned at the Tenth Census

(June 1, 1880) (Washington,

D. C., 1883), 129-30, 166-67, 201-02; G. F. Warren and F.

A. Pearson, Wholesale Prices for 213

Years, 1720-1932 (Ithaca, N. Y., 1932), 69-71,

84-86; Anne Bezanson et al., Wholesale

Prices in Philadelphia, 1852-1896 (Phil-

adelphia, 1954), 20-22, 84, 87, 253-55;

Joseph D. Weeks, "Report on the Average

Retail Prices of Necessaries of Life in

the United States," Report on Statistics of

Wages in Manufacturing Industries,

Tenth Census, vol. 20 (Washington, D.

C., 1886),

74-83; Cf. O. V. Wells, "The

Depression of 1873-79," Agricultural History, 11 (July,

1937), 242.

15. DeBow, Statistical View, 292;

Report on the Productions ofAgriculture, 129-30.

16. Improved acreage increased between

1850 and 1860 by 37.5 percent, faster

than the statewide average, from 59.2

percent of total farmland in Fayette County to

77.8 percent. At the same time the

number of farms and total farm acreage increased

by only 5.7 percent and 4.6 percent

respectively, both well below the statewide rate.

Computed from DeBow, Statistical

View, 169, 292, and Kennedy, Agriculture of the

U. S., 116, 211. In 1860 the total number of farms was not

reported for each county;

instead the Census reported only those

farms three acres or more in size. I have

assumed that, as in 1870, there were no

farms under three acres in Fayette County.

See Ninth Census, vol. 3, 360.

304 OHIO HISTORY

growth was therefore provided less by

new farm operators than by

new hands hired by Fayette farmers to

place increased acreage

under cultivation.

By increasing the demand for services,

agricultural expansion

and population growth in its rural

hinterland produced urban

growth in Washington Court House. The

town's population increase

from 569 in 1850 to 1,035 in 1860 was

greater, compared to other

urban places in the middle Ohio Valley

region, than its relative size

in 1850 would have led one to expect.17

Population growth was

based upon expansion in both commerce

and primary manufactures.

The 1850s saw Fayette's capital

invested in manufacturing and

value of manufactured products increase

faster than both the

statewide average and the rate of

Cincinnati's Hamilton County.

But while Cincinnati was diversifying

into secondary manufactur-

ing, Fayette's growth occurred

primarily in processing industries

such as flour-milling and distilling.18

By 1860, then, increased market

integration had produced urban

growth in Washington Court House by

stimulating specialized sta-

ple production and population growth in

its rural hinterland. The

performance of this interior trade

center shows that Muller's model

correctly predicts the direction of

change and identifies the relevant

variables. But it also reveals that

secondary manufactures were not

the only stimulant to urban growth in

this region during the 1850s.

Together with other interior trade

centers gaining railroad connec-

tions for the first time in the 1850s,

Washington Court House ex-

perienced the sort of growth based upon

commerce and primary

manufactures which urban centers on the

canal and early railroad

network had enjoyed during the previous

two decades.19 Washing-

ton Court House and other previously

isolated urban places

achieved market integration and

consequent growth characteristic

of second-stage development while other

centers, previously inte-

grated, experienced third-stage growth.

Still, Washington Court

17. Muller, "Selective Urban

Growth," 193.

18. Capital invested in manufacturing

increased by 279 percent in Fayette County

during the 1850s, compared to 156

percent for Hamilton County and 97 percent for

Ohio. Value of manufactured products

grew by 479 percent in Fayette County, 126

percent in Hamilton County, and 95

percent in the state. DeBow, Statistical View,

179, 295; Manufactures of the United

States in 1860 (Washington, D. C., 1865), 450,

456, 484.

19. Other exceptions, generally in newly

settled areas, included Muncie, Winches-

ter, and New Castle, Indiana, and

London, Ohio. Muller, "Selective Urban Growth,"

194-95.

|

Market Integration 305 |

|

|

|

House was only a way-station on the Cincinnati and Muskingum Valley Railroad, not a junction town in the new railroad network. Therefore one should expect to find its growth levelling off after 1860, as its hinterland stabilized and its manufacturing functions moved upward in the urban hierarchy.20 Such a process has been documented by Roberta Balstad Miller's study of a single urban community (Syracuse, New York) and its hinterland (Onondaga County) during the period 1790-1860. Miller has reported finding a decline in hinterland commercial and manu- facturing activity as a result of transportation-related urban growth. The railroads built through Onondaga County "indirectly contributed to the decline of hinterland industrial and commercial facilities by encouraging the development of superior facilities in the regional transportation center, Syracuse." The total population of the hinterland stagnated and, as it did, the proportion of its resi- dents living in country villages increased.21 Population growth and distribution in Fayette County during 1850-1880 conformed to the pattern found by Miller. For the county as a whole, neither the agricultural expansion of the 1860s nor the

20. Ibid. 21. Roberta Balstad Miller, City and Hinterland: A Case Study of Urban Growth and Regional Development (Westport, Conn., 1979), 87-88. |

306 OHIO HISTORY

agricultural slump of the following

decade produced population

growth higher than the statewide rate

(Figure 1). What population

growth occurred after 1860 took place

largely in Washington Court

House, which grew to 2,117 in 1870 and

3,798 in 1880.22 Conse-

quences of population growth included

the founding of new Baptist

("colored," 1855), African

Methodist Episcopal (1867), and Evangel-

ical Lutheran (1873) churches, and

construction of a new building

for the Roman Catholic parish organized

in 1852.23 The year 1873

saw the creation of a lecture

association to sponsor visiting

speakers.24 Meanwhile,

Washington Court House suffered from a

housing shortage which continued into

the mid-1870s, and local

lawyers, judges and juries had begun the

series of remonstrances

over the inadequacies of the courthouse

and jail that would lead in

the 1880s to construction of the present

building.25 The proportion of

the county population living in urban

places increased steadily from

seven percent in 1850 to 23 percent in

1880.26 These population

trends reflected Fayette County's

further integration into the

hinterland of Cincinnati. Population

growth in Washington Court

House was undoubtedly connected with its

position as local trans-

portation center. But what was the

precise link between transporta-

tion network centrality and population

growth?

The manufacturing sector's spurt of

growth in the 1850s, based

upon expansion in the processing

industries, was followed in the

1860s by much slower growth and a shift

in orientation.27 Distilling

disappeared from Fayette County, and the

number of gristmills de-

clined. Manufacturing establishments,

never large, grew slightly

22. Washington Court House accounted for

86.6 percent of county population

growth in the 1860s and 52.6 percent in

the 1870s, compared to 14.5 percent in the

1850s.

23. Presbyterian (1813), Methodist

Episcopal (1817) and Baptist (1840) congrega-

tions had been founded before the coming

of the railroad. Fayette County Herald, May

30, 1872; Ohio State Register, April

10, 1873; R. S. Dills, History of Fayette County

(Dayton, 1881), 489-511.

24. Ohio State Register, March

27, 1873.

25. Fayette County Herald, March

23, 1871, November 27, 1873; Ohio State Regis-

ter, February 4, 1875.

26. The figures for 1860 and 1870 were

nine percent and 17 percent respectively.

Urban places were defined broadly as

those places distinguished from their

townships in the aggregate census

population reports. Their size during the three

decades ranged from 87 to 3,798

population.

27. Fayette County's capital invested in

manufacturing increased by 33 percent in

the 1860s, while in Hamilton County it

increased 125 percent and statewide, 148

percent. Value of manufactured products

increased by 66 percent in Fayette, 68

percent in Hamilton, and 122 percent

statewide. Manufactures of the U. S. in 1860,

450. 456, 484; Ninth Census, vol.

3, 392, 557.

Market Integration 307

smaller: the number of hands per

establishment was 3.9 in 1860, 2.9

in 1870, and 3.3 in 1880.28 The largest

establishment in 1870 was

the Van Deman and Dews Woolen Mill,

which occupied a former

distillery in Washington Court House,

employing 15 hands. This

suggests that most Fayette County

manufactures were produced by

artisans in small shops catering to a

local clientele.29

In the 1870s all indices of

manufacturing in Fayette County

showed absolute declines. Capital

invested in manufacturing de-

creased by 29 percent, and the value of

manufactured products fell

off by 46 percent. This undoubtedly

reflected the impact of the de-

pression of the 1870s, but the

manufacturing sector in Fayette

County suffered far more than those of

Hamilton County and the

state of Ohio, both of which showed

positive though reduced growth.

By 1880 both the capital invested in

Fayette County's manufactur-

ing and the value of its manufactured

products had fallen below

their 1860 levels.30

Population growth in Washington Court

House after 1860 thus

took place in a context of stagnation,

if not decline, in the manufac-

turing sector. Processing functions located

in Washington Court

House during the 1850s moved upward in

the urban hierarchy as

transportation costs fell. Secondary

manufactures were never estab-

lished on more than a local basis due to

Washington Court House's

unfavored position within the railroad

network; in fact, even local

needs were supplied more and more by

larger centers.

The manner in which Fayette County's

last woolen mill closed

confirmed the triumph of the new order.

Since one railroad, the

Cincinnati and Muskingum Valley, had

supplied the market con-

nection which undermined local

manufacturing, it was fitting that

another railroad should be the instrument which finally killed this

central branch of Fayette County

industry. In 1877 the former Van

Deman and Dews mill found its retail

trade cut off by a new railroad

28. Manufactures of the U. S. in

1860, 450; Ninth Census, vol. 3, 557; Tenth Cen-

sus, vol. 2, Manufactures (Washington, D. C., 1883),

161. This contrasts with Miller's

finding that average number of workers

per firm increased in both Syracuse and its

hinterland. City and Hinterland, 99-100.

29. The distillery had employed twenty

persons in 1860. For a contemporary recog-

nition and lamentation of the lack of

manufacturing in Washington Court House, see

Fayette County Herald, November 5, 1874.

30. Manufacturing capital grew by 29

percent in Hamilton County and 18 percent

in the state, while value of

manufactured products increased by 37 percent in Hamil-

ton County and 29 percent in the state.

In 1880 Fayette County ranked 86th in

capital invested in manufacturing, and

84th in value of manufactured products.

Ninth Census, vol. 3, 392, 557; Tenth Census, vol. 2, 161-62.

308 OHIO HISTORY

line, the Dayton and Southeastern,

passing between it and the rest

of the community. Unable to expand into

wholesale trade, the own-

ers sold the machinery to a buyer in

Kansas. Thereafter, the wool of

Fayette County sheep would be carded,

spun and woven outside the

county.31

Manufacturing stagnation however did

not necessarily imply

general economic stagnation, as per

capita wealth grew at least

through 1870.32 It did mean a shift in

the relative sizes of various

functional groups within Washington

Court House, with corres-

ponding implications for social

structure. Two apparent shifts in the

functional-structure of the work force

were simply artifacts of a

change in census enumeration procedures

between 1850 and 1860

(Table 1).33 The enumeration

of women's occupations for the first

time in 1860 was responsible for both

an increase in the percentage

of service occupations and a percentage

decline in commercial posi-

tions. The railroad did bring some jobs

to Washington Court House

over the long term, and these were

reflected in the relative growth

of the transport sector.

The principal real shift was a decline

in the percentage of the

work force whose occupations could be

readily identified with manu-

facturing, from over half of the work

force in 1850 to less than

one-third in 1880. At the same time the

Unclassified group, consist-

ing primarily of those reported as

laborers without place or mode of

work, increased from two to 15 percent.

Possibly all of these laborers

actually worked in manufacturing; if

this were the case, the actual

relative decline in the crafts and

manufacturing category from 1850

to 1880 would have been substantially

smaller, from 53.0 to 45.5

percent. More likely, the growing

number of laborers were dis-

tributed over several functional

categories, including some or all of

the following: those who worked for

nearby farmers while living in

town (farm); those who hauled or

carried for merchants (commerce

31. Dills, History of Fayette County,

582.

32. Total wealth per capita grew from

$846 in 1860 to $1519 in 1870, an increase of

79 percent. Discounting for inflation

leaves a real per capita increase of 24 percent.

The value of real wealth per capita was $205 in 1850,

$535 in 1860, and $932 in 1870,

resulting in nominal percentage

increases of 161 percent during the 1850s and 74

percent during the 1860s. Discounting

for inflation leaves real per capita increases of

136 percent during the 1850s and 20

percent during the 1860s. Computed from the

manuscript federal censuses of 1850,

1860, and 1870, and from U. S. Bureau of the

Census, Historical Statistics of the

United States, Colonial Times to 1970 (Washing-

ton, D. C., 1975), 201. Ownership of

wealth was not reported in 1880.

33. Carroll D. Wright, The History

and Growth of the United States Census

(Washington, D. C., 1900), 152, 154.

Market Integration 309

Table 1:

Occupation of Work Force by Functional Category, Washington

Court House, 1850-1880 (in percentages)

Functional

Category

1850

1860 1870 1880

All

Commerce 26.1 17.8 21.0 20.4

Crafts and Manufacturing 51.0 39.5 32.2 30.4

Service 12.4 22.3 22.3 21.5

Government 0.7 3.1 2.3 1.1

Transportation 0.7 1.4 2.7 6.3

Farm 7.2 4.5 6.1 5.2

Unclassified 2.0 11.3 13.3 15.1

N 153 354 732 1086

Men

Commerce 26.1 21.6 24.6 23.6

Crafts and Manufacturing 51.0 42.6 35.9 32.0

Service 12.4 11.3 10.3 11.6

Government 0.7 3.8 2.8 1.4

Transportation 0.7 1.4 3.3 7.6

Farm 7.2 5.5 7.4 6.5

Unclassified 2.0 13.4 15.7 17.2

N 153 291 610 877

Women

Commerce 0.0 3.3 7.2

Crafts and Manufacturing 25.4 13.9 23.4

Service 73.0 82.0 62.7

Government Not 0.0 0.0 0.0

Transportation Recorded 0.0 0.0 0.5

Farm 0.0 0.0 0.0

Unclassified 1.6 0.8 6.2

N 63 122 209

Source: Manuscript

U. S. Census, Fayette County, 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880

or transportation); those who dug or carried for local

builders or for

the railroad (crafts and manufacturing,

transportation); those who

did odd jobs (service). In this case, decline in the

crafts and manufac-

310 OHIO HISTORY

turing occupations would have been the

principal functional

change.

A complementary perspective on economic

change in Washington

Court House may be obtained through

examination of the vertical

distribution of its work force (Table

2).34 Over the period 1850-1880

two groups, proprietary/low white-collar

and unskilled, increased in

relative size, while the remaining two,

professional/high white-

collar and skilled, experienced relative

decline. This overall pattern

held as well for the male work force;

for women a decline in the

skilled category was matched by an

increase among the proprietary/

low white-collar group, while the

remaining two groups in 1880

retained virtually the same shares as in

1860.

In Washington Court House as in other

communities, occupation

and opportunity to acquire property were

closely linked (Tables 3

and 4). Yet the town's increasing prosperity

in the period 1850-1870

meant that both the opportunity to

acquire property and the amount

held increased for nearly all

occupational groups.35 The single ex-

ception, skilled women workers, made up

only three percent of the

1870 work force.36

It is now possible to construct a

general picture of economic

change in Washington Court House and its

Fayette County hinter-

land in the aftermath of increased

market integration. The railroad

connection with Cincinnati brought

twenty years of prosperity to

Fayette County farmers by providing

improved access to a regional

processing center and a national market.

Agricultural prosperity

stimulated rural population growth

during the first decade of in-

tegration. After 1860 rural areas

experienced much slower popula-

tion growth as their urban center,

Washington Court House,

34. The discrepancy in size of the 1880

work force between Tables 1 and 2 is

composed of the following: 14 retired

persons who were considered to hold the status

of their former occupations although no

longer performing their functions; one person

classifiable by status but not by

function; two persons classifiable by function but not

by status.

35. The distribution of wealth changed

very little. For real estate holdings among

males 16 years of age and over, the Gini

index of inequality stood at .85 in 1850, .84 in

1860, and .84 in 1870. For total wealth

holdings among all persons aged 16 years and

over, the Gini index was .86 in 1860 and

.85 in 1870. Computed from the manuscript

federal censuses of 1850, 1860, and

1870.

36. Another, larger group, the male

proprietary/low white-collar workers (175 in

1870, 23.9 percent of the work force)

showed a nominal increase in mean total wealth

of 34.9 percent, but in fact experienced

a real decline of 10.2 percent when the

massive inflation of the 1860s is taken

into account. This was the only group whose

increase in mean wealthholding fell

behind the rate of inflation. It might seem that

this would imply a similar decline for

workers in commercial occupations, but the two

groups were not identical: the group,

male workers in commerce, registered a real

increase in mean total wealthholding,

1860-1870, of 27.7 percent.

Market Integration 311

Table 2:

Occupation of Work Force by Vertical Category, Washington

Court House, 1850-1880 (in percentages)

Vertical

Category

1850

1860 1870 1880

All

Professional and High

White Collar 24.2

11.6 5.6 5.6

Proprietary and Low

White Collar 19.6 24.3 25.4 28.8

Skilled 53.6 41.2 36.3 31.0

Unskilled 2.6 22.9 32.7 34.5

N 153 354 732 1099

Men

Professional and

High White Collar 24.2

14.1 6.7 6.7

Proprietary and Low White

Collar 19.6 27.5 28.7 32.1

Skilled 53.6 43.6 39.7 32.4

Unskilled 2.6 14.8 24.9 28.8

N 153 291 610 889

Women

Professional and High

White Collar 0.0 0.0 1.0

Proprietary and Low

White Collar Not 9.5 9.0 15.2

Skilled Recorded 30.2 19.7 25.2

Unskilled 60.3 71.3 58.6

N 63 122 210

Source: Manuscript

U. S. Census, Fayette County, 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880

absorbed most of the population increase taking place

in the county.

The population of Washington Court House continued to

grow fairly

rapidly until 1890, at least 30 years after

stabilization of population

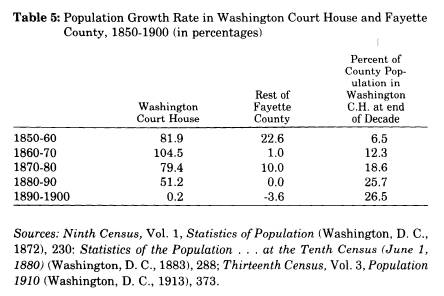

growth in its hinterland (Table 5). In 1850 only one of

every 15

residents of Fayette County lived in Washington Court

House; by

1890 one of every four did so.37

37. Commercial activity and population growth in

Washington Court House were

probably stimulated during the 1880s by the arrival of

narrow-gauge railroad lines

312 OHIO HISTORY

Table 3:

Propertyholding Incidence in Work Force by Vertical Occupation-

al Category, Washington Court House, 1850-1870

Percent Property-

Vertical holders

Category 1850* 1860 1870

All

Professional and High

White Collar 73.0 95.1 97.6

Proprietary and Low

White Collar 40.0 66.3 76.9

Skilled 35.4 43.1 61.6

Unskilled 0.0 9.9 34.3

Total 44.4 47.2 58.6

Men

Professional and High

White Collar 73.0 95.1 97.6

Proprietary and Low

White Collar 40.0 68.8 78.3

Skilled 35.4 43.3 65.3

Unskilled 0.0 18.6 52.0

Total 44.4 54.0 67.9

Women

Professional and High No No

White Collar women

women

Proprietary and Low

White Collar Not 33.3 54.5

Skilled recorded 42.1 25.0

Unskilled 0.0 3.4

Total 15.9 12.3

* - Only real wealth holdings were reported in 1850

Source: Manuscript

U. S. Census, Fayette County, 1850, 1860, 1870

from Dayton in 1877 and from Springfield in the

following year, and of a standard-

gauge line, the Columbus and Cincinnati Midland, in

1884. Both narrow-gauge lines

were converted to standard gauge during the early

1880s. By 1891 the railroad lines

through Washington Court House had become part of two

national east-west sys-

Market Integration 313

Table 4: Mean

Wealthholding of Work Force by Vertical Occupational

Category, Washington Court House, 1850-1870 (in

dollars)

Vertical

Category 1850* 1860

1870

All

Professional and High

White Collar 1189 6187 21078

Proprietary and Low

White Collar 977 4942 6856

Skilled 462 941 1842

Unskilled 0 37 370

All 727 2314 3713

Men

Professional and High

White Collar 1189 6187 21078

Proprietary and Low

White Collar 977 5294 7144

Skilled 462 952 1992

Unskilled 0 69 578

All 727 2753 4400

Women

Professional and High No No

White Collar women

women

Proprietary and Low

White Collar Not 250 2264

Skilled recorded 863 337

Unskilled 0 6

All 284 275

* - Real estate only in 1850; real and personal estate

combined in 1860 and

1870

Source: Manuscript

U. S. Census, Fayette County, 1850, 1860, 1870

tems, the Pennsylvania and the Baltimore and Ohio, and

two regional north-south

systems, the Cincinnati, Hamilton and Dayton and the

Ohio Southern. See Traveler's

Official Railway Guide (New York, 1893), and Henry V. Poor, Manual of the

Rail-

roads (New

York. 1891).

314 OHIO HISTORY

Population growth and economic

prosperity in Washington Court

House were based upon the town's

commercial role as local entrepot,

where farm products were sold and

shipped and where manufac-

tured goods were purchased. The most

obvious manifestation of this

function was the monthly stock sale day

instituted in 1871, when

buyers, farmers and livestock all

converged on Washington Court

House, converting the town itself into a

huge market.38 (Public

drinking on stock sale day dramatized

the dangers of widespread

liquor consumption and thus helped to

provoke the Women's

Temperance Crusade of 1873-74, in which

Washington Court House

women were prominent by their success.)

In the 1850s Washington

Court House played a part, although

probably a relatively minor

one, in the processing of some of the

farm products shipped from its

hinterland. By the 1870s, however,

nearly all of the farm products

shipped out of Washington Court House

were processed elsewhere.

In all likelihood, so were most of the

manufactured goods shipped

into Washington Court House and sold

there. The Cincinnati con-

nection thus influenced Washington Court

House in two ways: by

solidifying its position as trading

center for its local hinterland, thus

opening the way for further commercial

growth; and by setting an

upper limit to the development of

manufacturing, thereby closing

off a second avenue for growth. The

damage to local business feared

by the newspaper editor in 1870 had

indeed been done, though not

in the manner he expected.

By defining the possibilities open to

Washington Court House, the

process of integration also defined the

channels of opportunity with-

in the community. Local commercial

dominance brought prosperity

at least during the years of

agricultural expansion before 1870; it

also meant that Washington Court House

became a beneficiary of

population flows from its hinterland as

well as from outside the

county. The structural limit on

manufacturing growth set by

Washington Court House's position

vis-a-vis Cincinnati meant that,

while property mobility was increasingly

available before 1870,

occupational mobility into the skilled

trades which made up most of

the manufacturing sector was tightly

circumscribed.

Decline of occupational mobility into

the skilled trades was of

course not limited to Washington Court

House during the years

1850-1880. Although it affected

different trades at different times,

the advance of factory production during

these years generally

38. Dills, History ofFayette County, 356-57.

|

Market Integration 315 |

|

|

|

undercut the position of artisan producers and local manufacturers.39 But it was market integration that exposed Washington Court House artisans and manufacturers to the com- petition of factory production, by bringing outside manufactured goods to Washington Court House and by providing its hinterland farmers with the cash incomes they needed to purchase them. Since white collar positions as a whole also did not keep pace with population increase, the result was a steady growth at the bottom of the occupational hierarchy. If this situation was likely to produce discontent among the growing numbers of unskilled workers, such discontent may have been muted or redirected in Washington Court House as elsewhere by a high rate of geographic mobility, racial and ethnic divisions, and, for the geographically stable, increasing opportunity to acquire property. 40 In addition, unskilled workers in

39. This process has been carefully documented by Griffen and Griffen, Natives and Newcomers, chs. 7-8. See also Alan Dawley, Class and Community: The Indus- trial Revolution in Lynn (Cambridge, Mass., 1976), ch. 3. 40. Between 1860 and 1870 the crude persistence rate for unskilled male workers was 20.9 percent, compared to 61.0 percent for professional and high white-collar, 31.3 percent for proprietary and low white-collar, and 37.0 percent for skilled work- ers. In 1860, one-fifth of the male work force were black, while another two-fifths were foreign-born. In 1870 the two groups' proportions of the male work force were nearly reversed. |

316 OHIO HISTORY

Washington Court House were dispersed

rather than concentrated

in a single industry.

For Fayette County, then, urbanization

and industrialization did

not proceed together. Indeed, urban

growth in Washington Court

House was accompanied by what one might

call de-

industrialization, a relative decline in

the manufacturing sector of

its local economy. Increasingly

Washington Court House became a

place where products were bought and

sold rather than made. A

shift in the structures which

encompassed Washington Court House

had entailed both growth and structural

change within the com-

munity.