Ohio History Journal

A NEWLY DISCOVERED EXTENSION OF THE

NEWARK WORKS

By DACHE M. REEVES1

The study of aerial photographs of the famous Newark group

of prehistoric earthworks resulted in the discovery of a hitherto

unknown extension to these works. An interesting feature of this

discovery is the fact that an important section of the works was

found on the Newark flying field. This area had been prepared

for flying purposes after having been under cultivation for a long

period, and the former embankments were obliterated entirely.

It would have been difficult, if not impossible, to have located

these earthworks on the ground, but on the photograph they stand

out clearly. This is a striking illustration of the value of aerial

photography in archaeology.

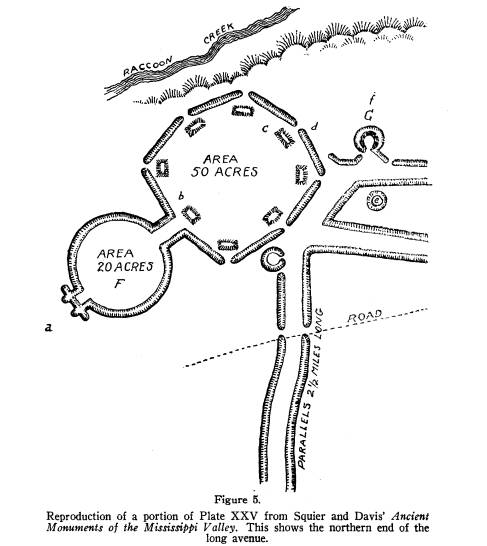

A portion of one of the aerial photographs is reproduced

herewith as Figure 1. This photograph was taken from 10,000

feet in January, 1934, the winter season being selected in order

to have the ground as bare as possible. Figure 4 is a tracing of

the salient features of the photograph, showing the L-shaped fly-

ing field and the parallel embankments forming a long avenue.

The small white circle with three arms on the flying field is the

usual symbol employed to mark airdromes.

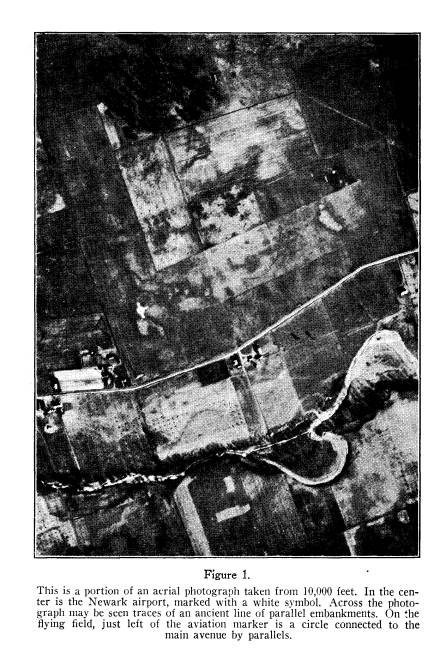

It will be observed that the avenue, after passing the airport,

makes a slight bend and continues to the edge of the terrace on the

north bank of the stream. Tracing backward, the avenue can be

followed almost to the octagon, the northern end being destroyed

by a residential suburb of Newark. The avenue is remarkably

straight, as shown in Figures 2 and 3.

1 Captain Dache M. Reeves, of the U. S. Army Air Corps, is one of America's

outstanding experts in aerial photography. For the past two years he has been co-

operating with the Society in an aerial survey of the ancient mounds and fortifica-

tions of Ohio with most gratifying results. The survey, rearing completion, will be

a definite asset to Ohio prehistory, and will place the State well in the forefront in this

most recent method of recording and interpreting major archaeological evidences.--

H. C. Shetrone.

(189)

|

190 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY |

|

The length of the avenue is 4300 yards, which agrees closely with Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis who stated the parallels were two and one-half miles long.2 However, 2 Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley (Cincinnati, 1848). |

|

EXTENSION TO THE NEWARK WORKS 191 |

|

|

|

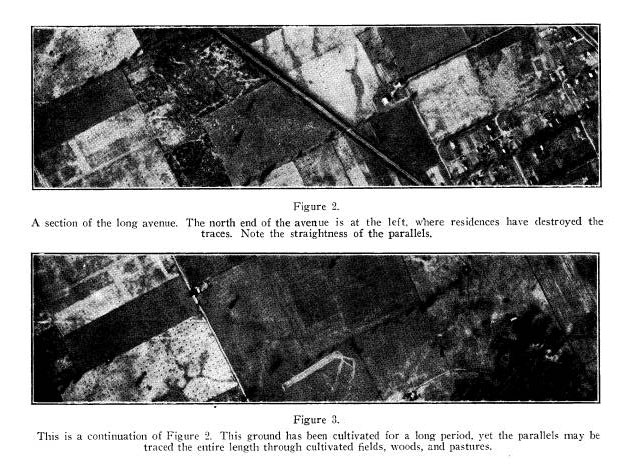

Col. Charles Whittlesey, who made the survey for

Squier and Davis, only followed the avenue a short distance. A

portion of his plan published as Plate XXV in Ancient Monuments is

repro- |

192 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

duced herewith as Figure 5. By failing

to follow out the length

of the avenue, Whittlesey missed

entirely the branch avenue and

circle on the Newark airport. It is

strange that this was over-

looked, as at the time the original

survey was made, nearly a hun-

dred years ago, the earthworks were

still undisturbed by culti-

vation.

A detailed analysis of these newly

discovered features will be

made in connection with a larger study

of the so-called "geome-

trical earthworks." However, it may

be of interest to discuss

briefly the significance of this

discovery. This Newark avenue

is the longest straight line of parallel

embankments constructed

by prehistoric builders and demonstrates

a considerable knowledge

of elementary surveying. Like the

majority of similar avenues,

it ends at a stream. It is possible when

other prehistoric sites

are studied further, that all such

avenues will be found to lead to

a running stream. This would indicate

that the purpose of build-

ing the parallel embankments was to

provide a passage-way for

processions of a ceremonial or sacred

character.

It is puzzling to note that this Newark

avenue extends over

two miles from the octagon to a small

stream, whereas the octagon

is located within a short distance of

Raccoon Creek, and if the

avenue had extended north instead of

south, it need only have

been about a hundred yards long.

Furthermore, Raccoon Creek

is a larger stream than Ramp Creek on

the south.

A short distance from the southern

terminus of the avenue,

a side avenue leads off to a small

circle. This side branch is not

a true parallel, as the two walls

converge slightly as they approach

the main avenue. The reason for this was

found in a small knoll

at the inner angle of the airport. The

north wall of the side

avenue was shifted slightly south in

order to avoid climbing the

knoll. Yet the main avenue pursues a

straight course regardless

of the varying slope of the ground.

At the center of the junction between

the main avenue and

the side branch, traces of a circular

earthwork can be detected on

the photograph. This may have been a

circular mound with sur-

rounding ditch, but this is only a

guess, as the destruction is so

EXTENSION TO THE NEWARK WORKS 193

complete the exact character of this

object cannot be determined.

Excavation at this point might clear up

the difficulty. The pur-

pose of the small circle and side avenue

is unknown. Further

study of earthworks may yield some

definite information.

The labor required to construct

earthworks of the size com-

prising the Newark group was immense

when the lack of tools is

considered. The builders possessed only

crude non-metal digging

tools such as shell and wood, and their

only means of transport-

ing the material was in basket-loads on

their backs. Under these

circumstances, it required a powerful

motive to undertake and

complete such elaborate works. Whether

executed by forced labor

(that is, slaves, war captives, or

subjects of an American Cheops)

or by voluntary effort, the inspiration

for such structures of a

non-utilitarian character was,

undoubtedly, in the religious beliefs

of the builders.

To learn more about these prehistoric

people we must read

their records; not their written

records, as they left none, but the

evidences of their labor. A great deal

has been learned from a

study of pottery, stone artifacts and

other objects recovered from

graves and found in the fields, and the

study of their most dis-

tinguishing characteristic--the great

earthworks--will add much

to the knowledge of prehistoric America.

Unfortunately, for

over a hundred years, the farmer has

done his best to destroy

every earthwork within reach of his

plow, ably seconded by the

railway and highway constructors. It is

only in recent years that

efforts to preserve America's

antiquities have met with any suc-

cess, and meanwhile many monuments are

totally destroyed.

Some consolation is found in the

valuable assistance aerial

photography has contributed to

archaeological study. As in the

present case, photographs have enabled

surveys to be made of

earthworks previously obliterated. As

the method of air survey

comes into extended use, more and more

accurate data will be

accumulated as a basis for the study of

our prehistoric predeces-

sors on this continent.