Ohio History Journal

ESSAY AND COMMENT

Preservation of the Newsreel Films

of President Harding

by Robert W. Wagner

Efforts of the professional archivist in

his attempt to preserve historical

materials are often complicated by the very nature of

the substance he

is trying to preserve. For example, all

35mm. motion picture film from

1888 to 1951 was made with a cellulose

nitrate base which makes the

reels highly flammable and under some

circumstances highly explosive.

A partially decomposed nitrate film may

ignite spontaneously at 120

degrees F., or even at 105 degrees F.,

if deterioration is far enough advanced.

Another material, triacetate, or so

called "safety" film, was used on 16mm.

and, since 1951, for all 35mm., 70mm.,

and magnetic film and tapes. But

the problem of proper storage of this

film remains. The optimum storage

place for archival films would be in an

airfiltered room at 60-70 degrees F.,

with a relative humidity of 40 to 50

percent. It is now the opinion of the

commerical producers of this film that

black-and-white films should last

as long as high quality paper records,

in proper storage areas.

In 1952 officials of the Library of

Congress, in an effort to find a way

to restore to usefulness its collection

of photographic prints on bromide

paper dating from 1894 that had been

accepted by the United States

Copyright Office as evidence of

ownership of original 35mm. nitrate

motion picture negatives, sought the aid

of the Academy of Motion Picture

Arts and Sciences. Mr. Kemp R. Niver of

the Renovare Film Company in

Hollywood was contacted, and he worked

for more than ten years to develop

a restoration printer. In doing so, he

found it necessary to identify and

solve some twenty-seven separate and

distinctly different technical problems

in the conversion of images from the

opaque bromide paper onto new

16mm. acetate film.

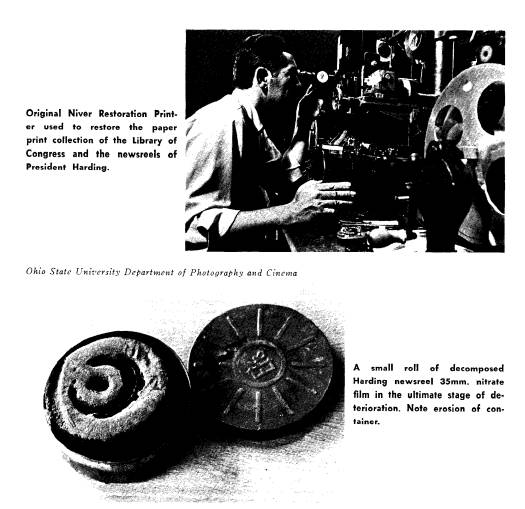

Restoration of archival film in Ohio has

been significantly aided by

the presentation in 1967 of the original

restoration printer made by Niver

to the Ohio State University's

Department of Photography and Cinema.

The first significant task of an

archival nature employing the use of the

new equipment was the project to

preserve the fast-deteriorating 35mm.

newsreel prints of the presidential

years of Warren G. Harding. In 1967,

at the initiative of Daniel R. Porter,

Director of the Ohio Historical

Society and custodian of the film, the

collection of newsreels was removed

from the Ohio State Museum and

transferred to a specially prepared air-

conditioned fireproof room used by the

Department of Photography and

Cinema where cautious handling of the

reels was begun.

|

The identifiable stages in decomposition of nitrate film were all present in the Harding collection, from the discoloration and fading of the image, to the brittleness and flaking of the emulsion, to the sticky or "tacky" condition accompanied by the erosion of the images and a softening and blistering of the base, to a solidification of the layers of film with a frothy exterior appearance, and finally to the appearance of a clinging, brown powder having a very acrid smell, denoting the ultimate stage of decomposi- tion. Some of the material was in good condition while other reels had deteriorated to the stage where it is necessary to destroy the film before it destroys itself. After the retrievable parts of the old film had been transferred onto new 16mm. film, all the old nitrate film was ignited on the university dump, where it burned with a fury which cannot be extinguished by any known means since it produces its own oxygen; it will even continue to burn under water or when sprayed with carbonic acid snow. The newsreel films in the Harding collection were shot by the major motion picture companies of the early twenties, such as International, Pathe, and Fox. Depicted are the highlights of the President's career after |

140 OHIO HISTORY

his election in 1920 until his death in

1923. The film record, however, is

fragmentary and consists of a sequence

of snapshots; it is not a "documen-

tary" presentation as television

viewers of the sixties have come to expect.

It shows the traditional stereotyped

"image" of the American President:

the golfer, the shaker of hands, the

friend of the weak (the American

Indian in Harding's case), the fisherman,

the public ceremonial figure

dedicating monuments and saluting at

parades, and the lover of children

and dogs. But the unrelenting camera eye

reveals Harding to greater

depths than surface gestures, if one is

alert enough to distinguish between

the trivia and the profound.

One may ask whether the restoration of

archival film is worth the cost

and effort. The cost for the Harding

films was from $200 to $300 per 10-

minute 35mm. reel, and the collection

now includes 1600 feet of film

recovered from about 2500 feet of the

original. The time required for

the job included 357 man-hours by highly

trained specialists. Would we

not today treasure a film record of

generations past? Of Alexander the

Great, Julius Caesar, George Washington,

or Napoleon Bonaparte? Do

we of the present generation, therefore,

not bear a responsibility to future

generations to preserve a film record of

our times? With the development

of the Niver Restoration Printer the

immediate technical problems of

preservation have been solved. Now what

is needed is a desire backed

by the necessary funds to support

programs aimed at improving the

technology for restoration work and for

perpetuating our motion picture

heritage--a form of human communication,

creative expression, and

historic documentation so unique to the

United States that cinema has

almost become our second

"language."*

ROBERT W. WAGNER

The Ohio State University

* An expanded version of this article,

entitled "Motion Picture Restora-

tion," appears in The American

Archivist, XXXII (April 1969), 125-132.