Ohio History Journal

LEONARD ERICKSON

Politics and Repeal of

Ohio's

Black Laws, 1837-1849

During the campaign of 1846 the

Cincinnati Gazette reported that Democratic and

Liberty men viewed the National Road

(40th parallel) as a Mason and Dixon line

across Ohio, as far as the Black Laws

were concerned.' That same year a related

proposition, that a person's attitude

towards these laws varied according to how

many Negroes he had as neighbors, was

voiced by a Whig Representative, T. R.

Stanley from Scioto and Lawrence

counties, when he asked:

Who are those that clamor for the repeal

of this law? Are they those who will be affected by

its repeal? No sir. In all the eleven

counties of the [Western] Reserve, there were, in 1840,

but 592 Negroes. In the single small,

hilly county of Gallia, there were 799; more than one-

third greater than the whole number upon

the Reserve.2

The Black Laws to which these remarks

refer were those of 1804 and 1807. They

required a certificate of freedom and

bond for Negroes migrating into Ohio and for-

bade "black or mulatto"

testimony in court cases where a white was a party. Later,

after the turn of the century, Robert

Chaddock, in his pioneer study of Ohio peo-

ples, repeated the early beliefs when he

argued that the legislators' attitudes, in 1839

at least, respecting repeal of the Black

Laws depended upon the geographical area

represented by the Assemblyman and upon

the numbers of Negroes in his con-

stituency.3 As we shall see,

such an explanation is incomplete.

While the details of the political deal

by which the Black Laws were finally re-

pealed in 1849 have been well recounted

by such contemporaries as A. G. Riddle

and Norton Townshend, the course of

repeal attempts before that date has largely

1. Quoted in Herald and

Philanthropist (Cincinnati), July 29, 1846. An abolitionist paper

elaborated

on the parallel: As far as slavery and

abolition were concerned, it wrote, "Brown county is South Caro-

lina, Hamilton is Louisiana, and Warren,

Mississippi. Columbiana, Trumbull, Ashtabula and Cuya-

hoga, are Pennsylvania, Massachusetts,

Vermont and Connecticut, respectively, and the National road is

Mason and Dixon's Line. "

Anti-Slavery Bugle (Salem), January

31, 1846.

2. Ohio Statesman (Columbus), February 10, 1846.

3. Salmon P. Chase, ed., Statutes of

Ohio and of the Northwestern Territory, ... from 1788 to 1833 ..

(Cincinnati, 1833), I, 393-394,

555-556. In respect to the resolution against repeal in 1839, Chaddock

wrote, "An analysis of this vote

shows that the demand for repeal came from the northern part of the

state where the people did not feel the

evil of the negro's presence. The southern counties were still a

unit as to the wisdom of these

laws." Robert E. Chaddock, Ohio Before 1850; A Study of the Early In-

fluence of Pennsylvania and Southern

Populations in Ohio (New York, 1908),

85.

Mr. Erickson is Professor of History at

Drake University.

154

Black Laws Repeal 155

been neglected.4 This study

will examine these repeal attempts, and by analysis of

votes during the late 1830's and the

1840's show that geography and the density of

Negroes in the representative's

constituency (electoral district) could be factors in

accounting for Whig votes, but not for

those of Democrats, on repeal attempts. The

Democrats were anti-repeal whether they

were from north or south of the National

Road; whether they came from

constituencies with just a few or with hundreds of

Negroes. Because of this consistent

voting record before 1849, Democratic support

of repeal in that year is all the more

incredible and fascinating.

A serious and systematic attempt to

secure the repeal of the Black Laws began

with the rise of militant abolitionism

in Ohio during the mid 1830's. Reformers in

this movement opposed all laws related

to "distinctions on account of color," partic-

ularly the "Testimony Clause"

which forbade Negro testimony in cases where a

white was a party, and they voiced their

opposition through petitions presented to

the General Assembly. Legislative action

which came as a result of this abolitionist

pressure for repeal can be separated

into two phases, dividing at 1844. During the

first phase there was no serious

activity by either the Whigs or the Democrats for re-

peal. In the second, repeal activity was

quickened; and in the wake of disruptive

political activity by abolitionists,

coupled with a waning of morale of the Demo-

cratic party in Ohio, the question of

the propriety of the Black Laws on the statute

books became much more prominent in the

minds of the legislators. While the

bulk of the present study deals with the

second phase, a few words about activity be-

fore 1844 are necessary.

The behavior of both parties before the

election of 1844 must have been dis-

couraging even to the most optimistic

Negro of that day. What friends he had in

the Assembly were Whigs, but by no means

were all Whig representatives friendly.

With a Whig Assembly in 1837-38 that

party could muster a majority of only one

among its members against a motion in

the house to postpone a bill to repeal the

Testimony Clause; and in the senate only

one other Whig, Benjamin Wade, joined

Leicester King in favor of the latter's

proposal to repeal that portion of the school

law excluding blacks and mulattoes.5

In the 1843-44 Assembly the Whigs again

had a majority, and again the repeal of

the Testimony Clause failed; indeed, there

was not even a recorded vote on

postponement. Democrats were even less sympa-

thetic to calls for repeal. In fact

during the 1838-39 Assembly, responding to a re-

port by Leicester King asking for

repeal, they had passed, with some Whig support,

resolutions which censored abolitionist

activities and asserted the propriety of the

4. A. G. Riddle, "Recollections of

the Forty-Seventh General Assembly of Ohio, 1847-48 [1848-1849],"

Magazine of Western History, VI (1887), 341-351; Norton S. Townshend, "The

Forty-Seventh General

Assembly-Comments on Mr. Riddle's

Paper," Magazine of Western History, VI (1887), 623-628; Towns-

hend, "Salmon P. Chase," Ohio

Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, I (1887), 117-118; Townshend

to B. W. Arnett, April 8, 1886, in The

Black Laws! Speech of Hon. B. W. Arnett ... March 10, 1886, pp.

32-33.

5. Ohio, House Journal, 1837-38, p.

696; Ohio, Senate Journal, 1837-38, p. 509; State Journal and Po-

litical Register (Columbus, semi-weekly), February 27, 1838. There is no

official listing of party affilia-

tions of the Assemblymen for this period

in the journal of either house, or elsewhere. Only the counties

of the members are given. Party

newspapers, therefore, were used to determine political affiliation; see

Ohio State Journal and Columbus

Gazette (Columbus, weekly), October

30, 1835, October 21, 1836; Daily

Journal and Register (Columbus), November 30, 1837; Journal and Register (Columbus,

semi-weekly),

October 26, 1838; Ohio State Journal (Columbus,

tri-weekly), October 21, 1843, October 31, 1844, Octo-

ber 21, 1845; Ohio State Journal (Columbus,

daily), December 7, 1846, October 19, 1847, November 30,

1848; Ohio Statesman (Columbus),

October 15, 1842; Cincinnati Gazette, December 8, 1842; Ohio Re-

pository (Canton), October 19, 1843, January 7, 1847; Cleveland Plain

Dealer, October 24, 1848.

156

OHIO HISTORY

Black Laws. Four years later they showed

the same hostility when they unanimously

rejected a repeal bill.6

This first rather dismal phase was not

entirely a time of discouragement for

friends of civil rights since it was the

formative period for abolitionist political

power. During the campaigns of the late

1830's abolitionists questioned candidates

about their stand on repeal and on other

matters of abolitionist concern.7 In the

1840's they formed first the Liberty

party, and then joined others in the Free Soil

party where they constituted a small,

but at times, crucial political force.

What did the appearance of abolitionism

mean for Ohio politics? Editors of

newspapers of the two major parties soon

came to appreciate the importance of the

abolitionist vote to the Whigs. In

analyzing the 1838 election one Whig editor wrote:

"That party [abolitionists] at this

time hold[s] the balance of power in a number of

counties of the State, sufficient to

decide the party complexion of the Legislature."

In 1842, we are told, the Whigs were

defeated by a union of "two hostile interests"

(Democrats and Liberty men), a union

which was brought about "as a result of a

transient sentiment of disgust on the

part of the feebler, because its particular dog-

mas could not be engrafted at once upon

the creed of the Whig party." While the

Whigs did win the election two years

later, the margin of their gubernatorial candi-

date over his Democratic rival was only

1,271. The Liberty nominee polled 8,898

votes. The Whig's small numerical

superiority obviously was precarious. Should

abolitionist voters choose to back

non-Whig candidates, as they had in 1838 and

1842, the Whig party was in trouble.

Probably not inaccurately, the Democratic

Ohio Statesman claimed it was the Whig awareness of this pivotal

Liberty strength

that had brought about Whig repeal activity

in the 1844-45 Assembly. The paper's

editor, Sam Medary, explained: "The

abolitionists, the coons [Whigs] believe, hold

the balance of power in Ohio, and

fearful of defeat without their aid, they now at-

tempt to woo them into their

embraces."8

It probably is not without significance

that during the 1844-45 Assembly two of

the most prominent Whig journals in the

state called for repeal of all or part of the

Black Laws.9 At the same

time, Democrats were being split by differences over cor-

rect banking policy, and their morale

was seriously weakened as they became dis-

pleased with Polk for his handling of

the Oregon Treaty of 1846, his favoring of

southerners in the matter of patronage,

and his veto of harbors legislation which

would have benefitted Ohio.10

In the wake of this erosion of

Democratic morale the Whigs dominated the As-

sembly until the election of 1848 (there

was a tie in the Senate for the 1846-47 ses-

6. Ohio, House Journal, 1838-39, pp.

234-235; 1842-43, p. 859: 1843-44, p. 69, 72, 106, 202: Weekly

Ohio State Journal (Columbus), January 10, 1844.

7. Of course there was some pressure on

Democrats as well as Whigs, especially in such abolitionist

areas as the Western Reserve, but

ordinarily an abolitionist vote withheld or given to the Liberty or Free

Soil parties was a vote lost to the

Whigs. In the 1848 election, only one or two representatives of the Free

Soil party received Democratic

endorsement, compared to five by the Whigs.

8. Ohio State Journal and Register (Columbus,

semi-weekly), October 24, 1838; Weekly Ohio State

Journal (Columbus),

October 19, 1842; Ohio, House Journal, 1844-45, p. 9; Ohio Statesman (Columbus),

March 28, 1845.

9. They were Ohio State Journal and

Cleveland Herald Weekly Ohio State Journal (Columbus), Feb-

ruary 22, 1845; Annals of Cleveland, XXVII

(1844), item 1162.

10. Ohio Statesman (Columbus),

March 30, September 4, 1846; Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 23,

June 14, 1843, January 21, 1848; Francis

P. Weisenburger, The Passing of the Frontier: 1825-1850 (Carl

Wittke, ed., The History of the State

of Ohio, III, Columbus, 1941), 415-440; Eric Foner, "The Wilmot

Proviso Revisited," Journal of

American History, LVI (1969), 271-274.

Black Laws Repeal 157

sion). In this second Whig-dominated

phase activity regarding repeal of the Black

Laws was intensified. The period began

with a near-success. In February 1845

friends of repeal caught their foes with

enough absent members, so the Democrats

claimed, to slip through the senate, by

a vote of 17-16, a bill which would have

amended the Testimony Clause to permit a

Negro to testify provided he could get a

white man to attest to his character.

The opposition was alarmed. The Statesman

saw this as the first step towards

opening the schools to Negroes and encouraging an

influx of them from the South. The

Dayton Empire rang the tocsin:

Are you ready for this state of things?

We appeal to the laboring portion of our fellow coun-

trymen. Are you ready to be placed on a

level with the "niggers" in the political rights for

which your fathers contended? Are you

ready to share with them your hearth and your

house? Are you ready to compete with

them in your daily vocations.11

These fears did not materialize as the

bill failed in the house, where 12 Whigs

joined 18 Democrats to defeat it 30 to

23. So ended the first Assembly of the second

Whig-controlled phase. Later

abolitionist charges of Whig hypocrisy-that they

simply used the promise of repeal to get

votes and then did not deliver-were per-

haps somewhat unfair since what support

repeal did get came almost entirely from

that party. (See Map 1) Yet, undeniably,

enough Whigs did drag their feet on the

whole matter to keep the Black Laws on

the books. In 1846, with substantial major-

ities in both houses (44-28 and 21-15),

they postponed, tabled, recommitted, or

amended to kill bills that would have

repealed all or parts of the laws and permitted

Negroes to use public school funds.12

The Anti-Slavery Bugle was rather sarcastic

about the whole business:

Every body who put faith in the promises

of Whig leaders, anticipated the speedy repeal of

the odious Black code. Action was

however put off from day to day, there were so many

more important things to be attended to-there were dogs to

be taxed and grave-yards to be

protected, Insurance companies to be

chartered and Banking corporations to be defended,

License laws to be re-modelled and

gambling laws to be enaceted, new counties to be erected

and old quarrels to be revived, party

squabbles to be attended to and speeches made for

Buncombe... 13

These were uncomfortable days for

politicians regarding repeal, for obviously nei-

ther major party could satisfy all

sections of the state. Highland County's Represen-

tative Ezekiel Brown's tally sheet for

the house vote in 1845 (on senate bill for repeal

of the Testimony Clause) contained the

notation "dodged" for three Whigs and four

Democrats.14 A Columbus

correspondent of the Anti-Slavery Bugle wrote that the

timidity of the legislators was

incredible, and added, "It is said that men would

rather be knaves than fools."

Considering how emotional people could be about

the Black Laws, it must have taken

courage for Whig nominee, William Bebb, to

run in 1846 with repeal of the Testimony

Clause as a prominent part of his guberna-

torial campaign. There were parts of the

state where this was precarious business.

For example, in Portsmouth a Whig editor

wrote that while he would vote for Bebb

11. Ohio, Senate Journal, 1844-45, pp.

411-416, 450-452, 457-459, 479-483; Weekly Ohio State Journal

(Columbus), February 19, 1845; Ohio

Statesman (Columbus), February 7, 8, 13, 21, 1845.

12. Ohio, House Journal, 1844-45, p.

822; 1845-46, p. 546, 734, 742; Anti-Slavery Bugle (Salem), March

13, 1846; Cincinnati Herald, February

17, 1847; Ohio, Senate Journal, 1845-46, p. 383, 506, 711.

13. Anti-Slavery Bugle (Salem),

February 20, 1846.

14. Tally sheet, VFM 1612, Ezekiel Brown

Papers, Ohio Historical Society.

|

158 OHIO HISTORY

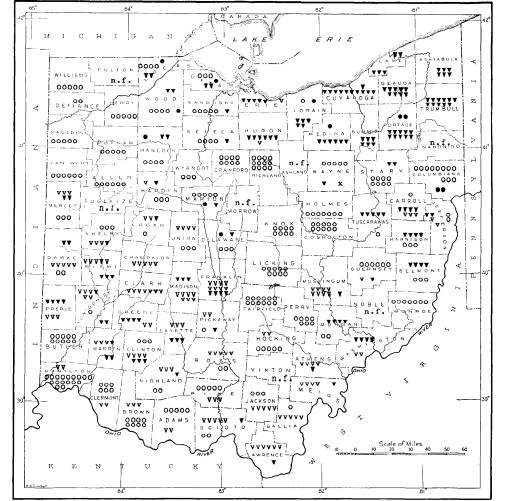

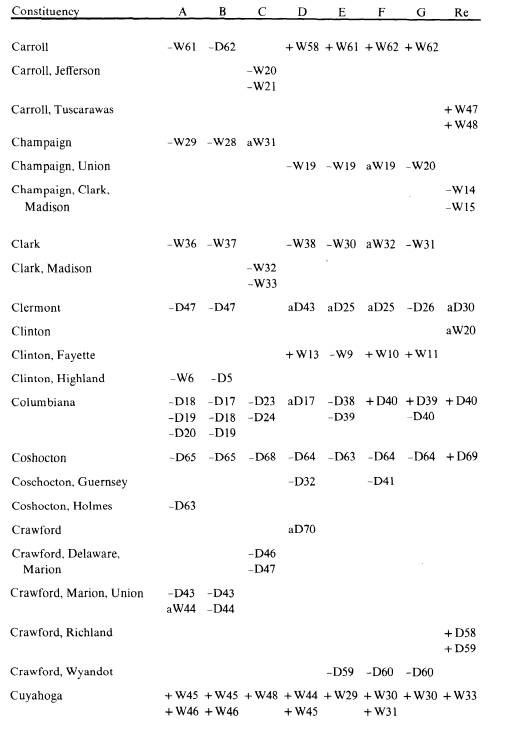

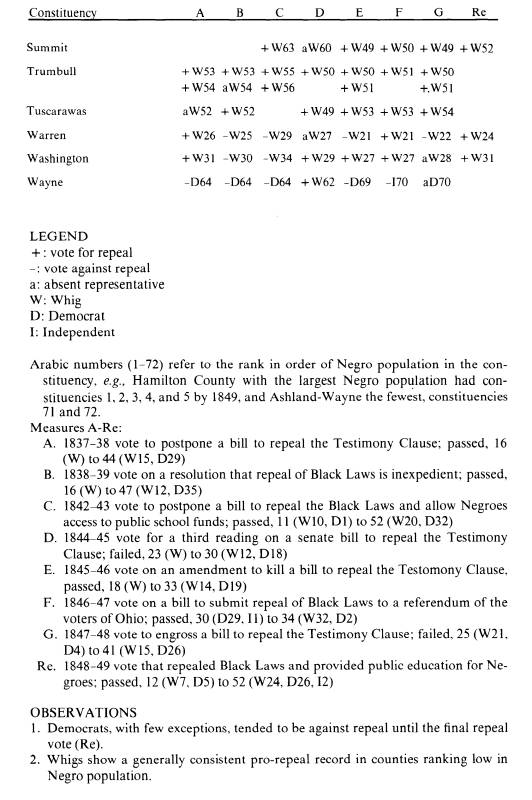

MAP ONE House Votes on Black Laws Repeal Measures, 1837-1848 |

|

LEGEND v: Whig, for repeal v: Whig, against repeal *: Democratic, for repeal o: Democratic, against repeal x: Independent, against repeal n.f.: county not formed by 1848

OBSERVATIONS 1. This map shows that during years 1837 to 1848 geography was not a factor in how Democrats voted on repeal. 2. For the Whigs it shows that the bulk of their opposition came from constituencies south of the National Road (40th parallel), but even below this line there were pockets of votes favorable to repeal. 3. It also shows that the stronghold of Whig support for repeal was in the Western Reserve, the eleven counties in the northeastern section. |

Black Laws Repeal 159

he could not condemn Whig friends who

would refuse to vote for the nominee of

the party, in the light of his repeal

position.15

The Democrats quite naturally looked

forward to a good Whig family brawl on

this issue; but in September they, too,

were drawn into the fray when the Whigs

charged that in 1838 their candidate,

David Tod, had been in favor of Black Laws

repeal. Indeed, they added, he had not

objected to public school funds being used

for Negro education. Whigs subsequently

pictured Tod and his Democratic back-

ers as favoring mixing the schools,

while on his part Tod was busy explaining to

Democrats in Scioto County and elsewhere

that he opposed repeal. In an anti-

repeal section of the state Bebb even

made a last-minute statement that he did not

favor admitting Negroes to jury duty, to

the franchise, or into the common schools,

and that he would prohibit them from

owning real estate. This statement, given in

Mercer County where there was

considerable unrest following an attempt that sum-

mer to settle John Randolph's freedmen

in the area, was made at the last possible

moment so that word of it would not

reach the Reserve in time to change the minds

of abolitionists who had been won over

by his pro-repeal statements earlier in the

campaign.16

In regard to Bebb it must be agreed, as

a Liberty paper argued, that the Whig ex-

cuse for his inconsistency, that he was

speaking for himself and not for other Whigs,

was rather lame, for naturally what the

gubernatorial candidate said appeared to

many to be a party commitment. It would

seem, however, that Bebb's equivocal

position on repeal, at least, was not

damaging since Tod lost by a greater margin

than he had in 1844.17 The campaign of 1846 was the first when

repeal of the Black

Laws was a major statewide issue, and it

appears that abolitionist concern for the

matter could no longer be ignored. Also,

it should be remembered that in even

numbered years during this period the

annually elected Assembly and the governor-

ship were at stake. The party in control

of the statehouse obviously would dispense

the patronage that went with such

control, and in years of presidential elections the

pressure for victory was even greater

since federal patronage was added to the pot.

With these factors in mind, it really is

not surprising that in 1846 Bebb both "fa-

vored" and "opposed"

repeal of the Black Laws and that Whigs attempted to ex-

ploit Democratic divisions regarding

proper party policy, particularly regulatory

legislation for banks, and, on the

national level, the matter of slavery in those terri-

tories that might be acquired as a

result of the Mexican War.

After the new Whig-controlled house

convened in December 1846 (the senate was

tied), the majority members acted on all

the talk of the campaign. But when they

finally did bring forth a repeal bill,

it was rather unheroic-apparently it took some

time to work out a scheme by which

anti-repeal Whigs could pass the buck. After

two bills for repeal had been introduced

in the house, but seemingly going nowhere,

a third was dropped into the hopper

which made repeal contingent on a voter refer-

endum, and passed. The senate did not

concur. Democrats ridiculed the whole

scheme. It called for the election to be

held in the spring when the turnout would

be light. More important, it seemed

absurd for the Whigs to favor a referendum for

this issue involving only a small

portion of the people when they had refused it ear-

15. Anti-Slavery Bugle (Salem),

January 23, 1846; Ohio Statesman (Columbus), September 9, 1846.

16. Ibid., October 7, 9, 1846; Weekly

Ohio State Journal (Columbus), September 16, November 10,

1846; Herald and Philanthropist (Cincinnati),

October 14, 1846.

17. Weekly Ohio State Journal (Columbus),

November 10, 1846; Cincinnati Herald, December 30,

1846; Ohio, House Journal, 1846-47,

p. 18.

160 OHIO HISTORY

lier for revising the state constitution

(expected to favor the Democrats) affecting the

whole population. This attempt to dodge

responsibility was even criticized by the

(Whig) Cincinnati Gazette.18

Abolitionists again rebuked the Whigs

for failure to effect repeal. Such bills

would have passed the senate if they had

been party issues, as were matters of bank-

ing and tariff, wrote the Anti-Slavery

Bugle. "The days of Bebbism cannot last for-

ever," commented the (Liberty)

Cincinnati Herald.19 And then,

ignoring Demo-

cratic opposition to repeal, the paper

said in connection with the senate voting:

All we ask... is that this party shall

come before the world in its own and not in borrowed

dress-that it shall confine its claims

to protection of Manufacturers, and the creation of

money facilities, and disavow all

pretensions to the defence and guardianship of the natural

rights of man ... that it shall not seek

to obtain the suffrages of the people on false pretenses

... it will save their future candidates

the trouble of being all things to all men, and every

voter that supports them will understand

that he is voting for Protection and Paper Money,

and not for the Rights of Humanity.20

Perhaps this abolitionist's displeasure

was in part prompted by the fact that since

the Whigs had majorities on the days

when votes in the senate were cast on bills in-

volving repeal (the house referendum

bill and two senate repeal measures) they

should have delivered. Bills for repeal

or partial repeal were also introduced in the

following Assembly (1847-48), both in

the house and the senate, and with the usual

result. Solid Democratic opposition,

plus substantial Whig help left the Black Laws

intact until the dramatic 1848-49

session.21

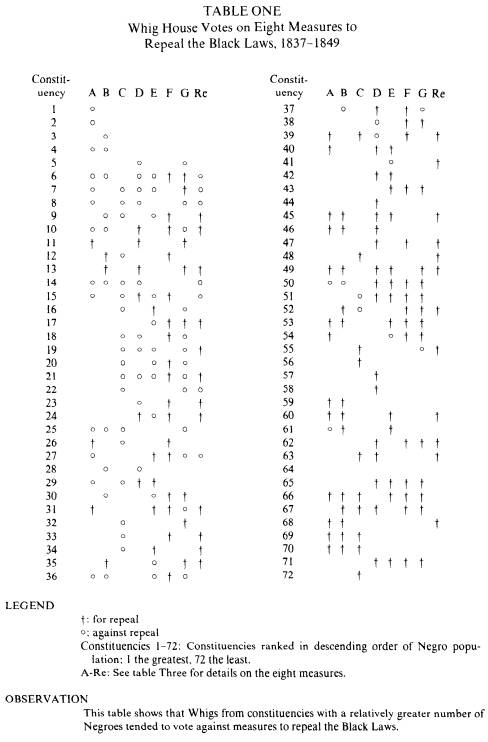

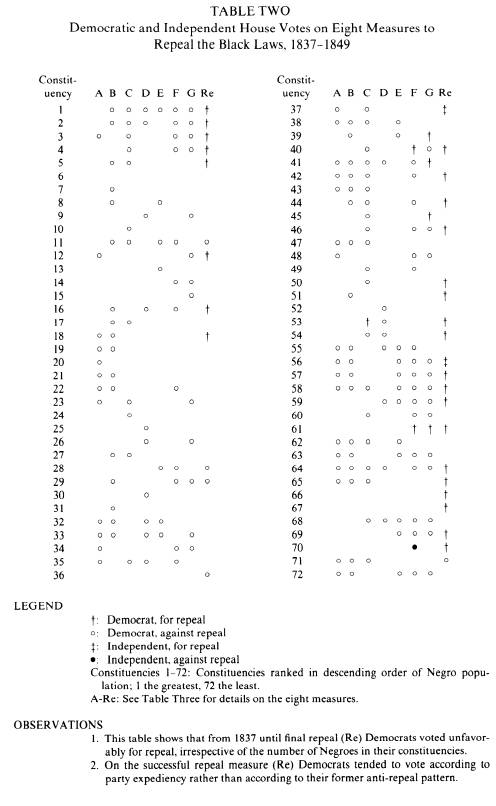

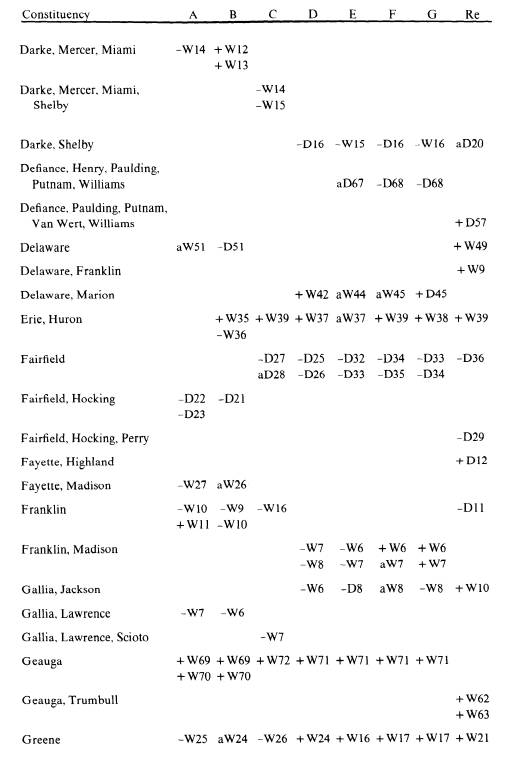

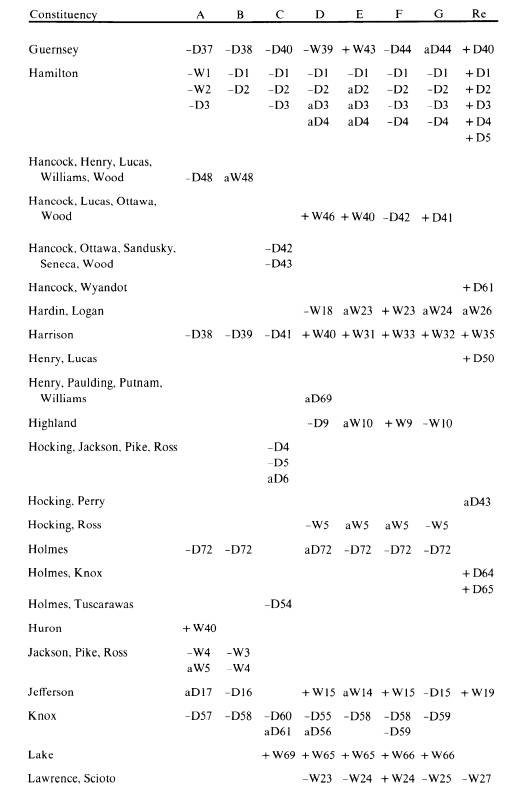

It might be appropriate at this point to

set the stage for that dramatic and im-

probable session of the 1848-49

Assembly. House votes on legislation mentioned

thus far will be grouped in such a way

that they may be examined in terms of geog-

raphy (Map I) and the number of Negroes

in the constituencies of the representa-

tives (Tables I, II, III, and Map II).

To help determine whether a representative's

vote was related to the number of

Negroes in his constituency the eight measures

concerning repeal have been arranged in

two tables, one for Whigs and a second for

Democrats and Independents. For each

table the seventy-two electoral districts of

the house are listed in order of the

number of Negroes in those constituencies at the

time of the nearest census-that of 1840

for 1837-38 to 1844-45, and 1850 for the

other Assemblies. For example, Hamilton

County with the greatest number of Ne-

groes was constituencies 1, 2, and 3 for

vote A (1837-38); Holmes County with the

fewest of any constituency was last at

72. The votes on the various measures are

designated A to G, and set apart in a

separate column under "Re" is the repeal vote

of 1849. It is hoped that by this arrangement

the reader can compare more easily the

voting of representatives from those

districts with comparatively numerous Negroes

with those that had only a few. Table

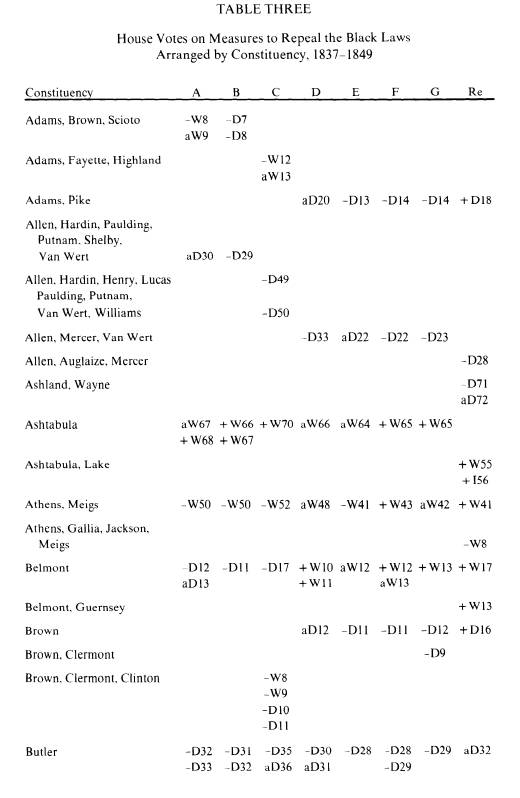

III identifies these votes, or absence of a vote, in

(text continued on page 169)

18. Ibid., 15, 127, 150-151,287,311,359,376,445, 499, 518-525;

Ohio, Senate Journal, 1846-47, p. 613;

Cleveland Plain Dealer, February

8, 1847; Ohio Statesman (Columbus), February 2, 19, 1847.

19. It is not certain which senate vote

distressed the Bugle. Before voting on the house bill, the senate

had already postponed two of its bills

for partial repeal. Ohio, Senate Journal, 1846-47, pp. 342-343;

Anti-Slavery Bugle (Salem), February 5, 12, 1847.

20. Cincinnati Herald, February

17, 1847.

21. Ohio, Senate Journal, 1847-48, p.

42, 409, 506, 516; Ohio, House Journal, 1847-48, p. 62, 222,

455-456.

|

Black Laws Repeal 161 |

|

162 OHIO HISTORY |

|

Black Laws Repeal 163 |

|

164 OHIO HISTORY |

|

Black Laws Repeal 165 |

|

166 OHIO HISTORY |

|

Black Laws Repeal 167 |

|

168 OHIO HISTORY |

Black Laws Repeal 169

terms of party affiliation as well as

the county or counties of the representatives.22

Map I shows whether the voting on the

repeal issue before 1849 was related to ge-

ographic area. On this map the votes are

recorded by coded symbols, but the

reader should be cautioned that the

number of symbols does not match the number

of votes. A separate symbol is given for

each vote by each representative in such

counties as Hamilton that had more than

one representative. In multi-county con-

stituencies a symbol is given for each

county in the constituency, even though a

number of counties grouped together in a

single district had but a single representa-

tive and a single vote. It is hoped that

this presentation will show how the political

power of the several counties of the

state was used in respect to repeal, even if the

power of the counties was unequal. To

the degree such use of political power re-

flected public opinion, the map will

show how various areas felt about repeal.

It must also be noted that the data in

Tables I and II are at times approximations.

New counties were formed during this

period and there is no way of knowing just

how many Negroes were lost to each of

the former counties when a new one was

formed.23 For the position in

the tables, in these cases, the author simply averaged

the population over the new counties.

For example, Vinton County had a colored

population of 107 in the 1850 census,

but since it was not formed at the time the

votes after 1845 were cast, the 107 were

divided equally among the five counties

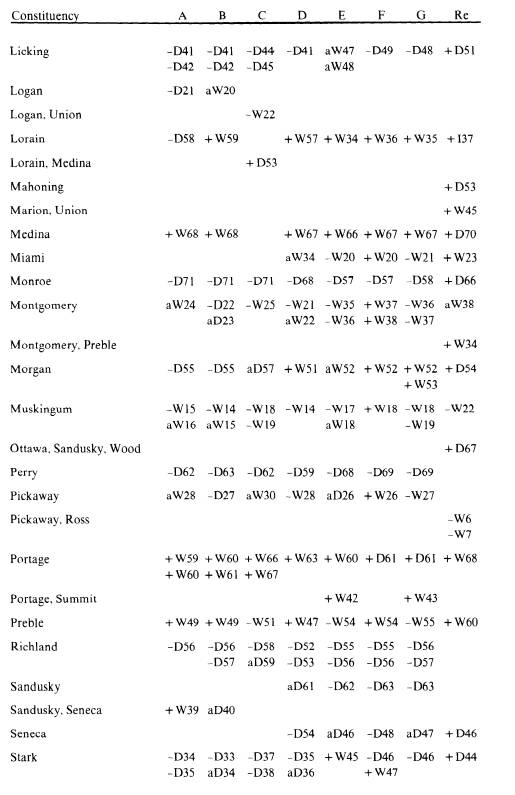

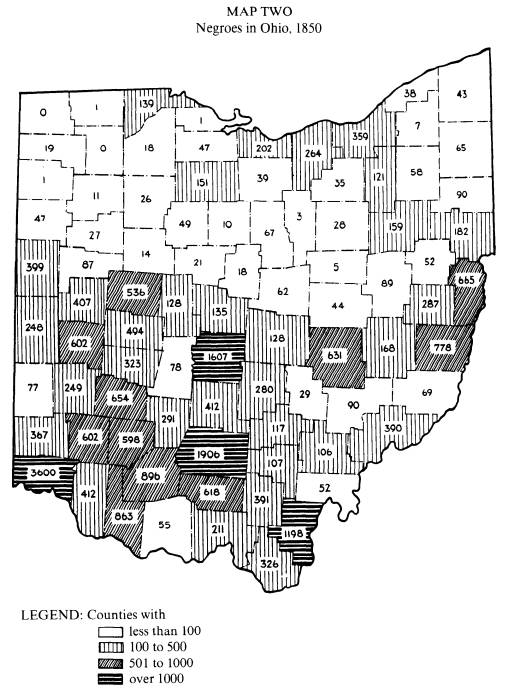

from which Vinton was formed. Map II

shows graphically the density of Negro

population in the various counties in

1850.

Examination of the tables and maps will

show that voting behavior regarding re-

peal was not simply a matter of

geography, as Chaddock implied; nor was racial

prejudice necessarily less where there

were fewer Negroes, at least as far as the vot-

ing during these years was concerned.24

Democrats consistently voted against re-

peal before 1849 regardless of whether

they came from Hamilton County, with the

most numerous blacks, or from Richland

and Wayne counties, which were north of

the National Road and had few Negroes.

Indeed, the Democrats cast only 7 favor-

able votes during the first seven

sessions surveyed; or stated another way, cast 188 of

195 of their votes (96.5%) against

repeal. (See Table III)

Whigs, on the other hand, did give most

of the support for repeal, but by no

means was it popular among the

membership in many parts of the state. From

Table III and Map I it can be seen that

representatives in the northeastern counties

(the Western Reserve) were

overwhelmingly for repeal; while those from south-

central counties (Ross, Pike, Scioto), the Mad River

counties (Champaign, Clark),

and Muskingum to the east were strongly

opposed. Outside of the relatively non-

committal referendum bill of 1846-47

(vote F) there was not a single favorable

Whig vote from such strongholds as

Montgomery, Muskingum, Athens, and Law-

rence counties. Table I shows that only

42 of their positive votes came from the

22. On Table III the constituencies for

all the sessions where votes were considered have been arranged

alphabetically by counties (or by the

first county in a multi-county constituency). All representatives are

accounted for-positive, negative or

absent. A blank spot, e.g., Carroll County on vote C (1842-43),

means the county's representation was

rearranged or reduced for that year. In Carroll's case it was

grouped with Jefferson County. This

particular mode of presentation was used to enable the reader, in

as many instances as possible, to see

the voting pattern of a particular county or grouping of counties over

the period being considered.

23. For the formation of new counties

during this period, see Randolph Downes, "Evolution of Ohio

County Boundaries," Ohio

Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, XXXVI (1927), 340-477.

24. Frank Quillen, in his study of the

nineteenth century Ohio color line, argued that prejudice in-

creased in proportion to the number of

Negroes in an area. The Color Line in Ohio (New York, 1913), 1.

|

DOCUMENTATION: United States Census, 1850, pp. 817-818. A similar map ap- pears in Francis P. Weisenburger, The Passing of the Frontier: 1825-1850 (Colum- bus, 1941), 46. |

|

170 OHIO HISTORY |

Black Laws Repeal 171

first thirty-six constituencies where

most of the Negroes lived. From Table III we

find that outside of the Reserve, Whigs

cast 87 negative votes, which was 56 percent

of all non-Reserve Whig votes. In light

of these figures it is evident that Whigs

fearlessly attacked this restrictive

legislation primarily in the eleven counties of the

Western Reserve.25

Although the votes in the senate were

not used for the tables or maps, the story

there was quite similar. In five

sessions from 1836-37 to 1847-48 there were bills

introduced to repeal all or parts of the

Black Laws. Of the 167 votes cast on five

measures (one from each session) 55 were

positive-all Whig. Of the 55 positive

Whig votes, 24 were cast by senators

from the Reserve. Of the 112 negative votes,

Democrats accounted for 78, and Reserve

Whigs for only 4-all on the first measure

in 1836-37.26

For over a decade, our data show, repeal

was stalled by a hostile combination of

Democrats throughout the state and of

Whigs from more heavily Negro-populated

areas outside the Reserve until 1848,

when some dramatic political developments

took place. By an apportionment law of

that year Hamilton County was split into

five election districts for the house.

Formerly each of the representatives from

Hamilton County had the entire county as

a constituency, and every voter of the

county could vote on each of the

representatives. By the new apportionment law a

Hamilton County voter could vote for

only one representative, the one running in

his district. The intention was to help

the Whig party pick up some seats where

Democrats customarily swept the county.

When the Whigs did indeed win two

seats, their opponents refused to accept

the results. In the dispute that ensued the

Democratic County Clerk issued

certificates of election to five Democrats, while

judges at the polls gave certificates

for two of the five seats to Whig contestants.27 In

such cases it was up to the house to

judge the dispute.

The 1848 presidential election in Ohio

only served to compound the confusion

when the Assembly convened in December.

Once again the Whigs turned to a mil-

itary hero, and this time a slaveholder

as well. The result was that many Reserve

voters, antislavery as they were, became

so disenchanted with General Zachary

Taylor's candidacy that they joined the

new Free Soil party and voted for its candi-

date, Martin Van Buren, though, as one

said, "God knows how bitter the dose is but

everything for the cause." Van

Buren carried half of the counties of the Reserve

and probably cost Taylor the state of

Ohio, which was won by the Democratic can-

didate Lewis Cass.28

It is doubtful that many Free Soilers

expected to carry Ohio for Van Buren, and

they did not. The election for the

General Assembly, however, was another matter,

for when the votes were counted, they

indeed had captured a number of seats and

as a result were a third political force

when the 1848-49 session convened. The

25. For his time Woodson probably had

the best insight about the Black Laws. He did not, however,

differentiate among Ohio Whigs when he

wrote: "Abolitionists, Free Soilers and Whigs fearlessly at-

tacked the laws which kept the Negroes

under legal and economic disabilities." Carter G. Woodson,

"The Negroes of Cincinnati Prior to

the Civil War," Journal of Negro History, I (1916), 16.

26. Ohio, Senate Journal, 1836-37, p.

148; 1844-45, p. 482; 1845-46, p. 711; 1846-47, p. 343;

1847-48,

p. 506. In both senate and house

sessions there were introduced during the later years of this period,

pairs of bills-one to repeal the

Testimony Clause, and a second to repeal the other Black Laws. In such

cases the Testimony Clause vote was used

since it was more important to friends of civil rights for

Negroes.

27. Riddle, "Recollections of the

Forty-Seventh General Assembly," 342.

28. J. M. Root to Giddings, September

13, 1848. Roll 4, Joshua Giddings Papers, Ohio Historical

Society; Weisenburger, Passing of the

Frontier, 468-470.

172

OHIO HISTORY

membership of the new house presented a

host of possibilities for political deals on

the judging of the Hamilton County

returns. Not counting the two contested seats,

there were 32 or 33 Democrats, 29 Whigs,

and 8 or 9 Free Soilers. Of the Free

Soilers, 5 had been endorsed by Whigs

during the campaign, 1 or 2 by Democrats,

and 2 were truly independent in that

they had run against candidates of both major

parties.29 A little addition

will show that if the Free Soilers who had campaigned

with either Whig or Democratic support

voted with the major party that endorsed

them on non-Free Soil matters, the

lineup would be 34 to 34, leaving the two Inde-

pendents with the deciding votes on

questions of organizing the house.

By way of background for understanding

why these Independents and the Demo-

crats voted as they did, it should be

recalled that in 1849, with no prospect of federal

or state patronage to benefit them and

with a growing suspicion of undue southern

influence in national Democratic

circles, Ohio Democrats were not about to pass by

an opportunity to improve their party's

position on the local level. The opportunity

was presented when the two Independents,

John Morse and Norton Townsend,

joined forces with them to capture

control of the legislature. The Democrats se-

cured from the Independents the

necessary votes to elect one of their members as

Speaker of the house and to seat the

Democratic contestants from Hamilton

County. As the other part of the

bargain, Democrats delivered the votes for the

election of a United States Senator of

Free Soil outlook, Salmon Chase, and also for

a better public education law for Negroes

and repeal of the Black Laws.30

In the opening days of the 1848-49

Assembly a number of bills were introduced

which would have repealed all or part of

the Black Laws. It is not certain why of all

the bills Morse's (HB52) was the one

that was pushed to a vote. His measure did

have the directness of repealing all

racial distinction laws, and we know that Chase

was quite anxious that Morse have

something to show for his voting with the Demo-

crats in organizing the house.31

Whatever the reason, Morse's bill passed the house

by a vote of 52-10, with 4 Democrats and

6 Whigs voting against the measure.

Later in the day a Whig and a Democrat,

who one correspondent reported had

locked themselves in the Sergeant at

Arms' room to dodge the vote, appeared, and

with their negative votes the final

count was 52-12. Townshend recalled later that

considerable party pressure was

necessary to secure passage, and he was probably

correct. One Whig reporter wrote,

"One Loco-foco followed another, like a flock of

sheep clearing a barn yard gate. The old

stagehorses from the Reserve sat in mute

astonishment."32

Then the senate had its turn.

Apparently, when the bill was taken up on the floor

29. Riddle listed eight Free Soilers;

Townshend the same ones, plus Hugh Smart, a Democrat from

Highland and Fayette counties.

Examination of the election returns in the Free Soil Banner indicates

that this paper considered Smart to be

of that party. Free Soil Banner (Hamilton), October 24, 1848.

30. See Townshend's accounts in

footnote 4 above. There were other offices elected by the Assembly

that were at stake, but that of Speaker

and U. S. Senator drew the most attention.

Beginning in 1829 blacks and mulattoes

were excluded from benefits of the common school fund. By

a law in 1848 they were allowed to

attend white schools (the regular district schools) in those districts

where there were fewer than twenty Negro

children, provided no protest was filed by a white patron or

taxpayer. In districts with twenty or

more Negro children, separate schools were authorized, and were to

be financed only by tax money on

Negroes. Laws of Ohio, 1828-29, XXVII, 72-73; 1830-31, XXIX, 414;

1837-38, XXXVI, 21; 1847-48, XLVI, 81-83.

31. Ohio, House Journal, 1848-49, p.

40, 46, 114; Ohio, Senate Journal, 1848-49, p. 81; "Letters of

Salmon P. Chase," American

Historical Review, XXXIV (1928-29), 544-545.

32. Ohio, House Journal, 1848-49, p.

197, 198; Western Reserve Chronicle (Warren), February 14,

1849; Townshend, "Comments on Mr.

Riddle's Paper," 625; Scioto Gazette (Chillicothe), January 31,

1849.

Black Laws Repeal 173

there were apprehensions that it would

admit Negro children into any common

school and adults to juries, and so it

was sent to the judiciary committee for study.

The committee reported out amendments

which specifically exempted from any re-

peal action the laws of 1831 regarding

poor relief and exclusion of Negroes from

juries, but the main features of Morse's

measure regarding public education for Ne-

groes and repeal of the Black Laws were

retained. The senate passed the bill, with

the amendments, 23-11, and the house

concurred with the changes.33 Thereafter the

black migrant need no longer post bond

for his Ohio residence, Negroes could tes-

tify in their own behalf, and their

children were in a better position to leave the edu-

cational wilderness.

On January 3, 1849, the Democrats

secured the Speakership of the house for their

party, and on the 26th the two

contestants of their party from Hamilton County

were accorded legitimacy. On January 30,

Morse's bill passed the house, and on

February 6 the senate passed a modified

version which subsequently became the

law of the state. How did Ohio political

circles view this victory for Negro civil

rights? As we have seen two house

members attempted to dodge the vote; others,

in the senate, rather ludicrously

proposed amendments exempting their con-

stituencies. When one examines Table II,

showing Democratic voting on previous

repeal attempts, and then compares this

record with the vote on HB52 (Re), it be-

comes obvious that the repeal vote was

about the ultimate in turnabout for the

Democratic party. One explanation

Democrats gave was that it was time to end the

Whig use of the repeal issue for party

purposes to attract abolitionist support. Per-

haps more than one Democrat agreed with

the Enquirer's correspondent that the

Black Laws were a repressive failure

and, if nothing more than on grounds of expe-

diency, should be repealed.34 Still,

after reviewing the record of Democratic voting

in regard to racial questions, these

explanations seem to have come after the fact.

In any case, this instance of

cooperation by Democratic legislators with abolitionists

appears to have been an aberration. During the year 1854 the Kansas-

Nebraska Act was passed which would

allow slaves to enter those territories where

previously they had been banned. The

reaction against the measure was so strong

that a new antislavery (Republican)

party was formed which became a major politi-

cal power in the state. Now the

abolitionists had an acceptable, if not always

happy, new political home, and neither

the setting nor the disposition for another

Democratic-abolitionist legislative bargain

occurred for the balance of the decade.

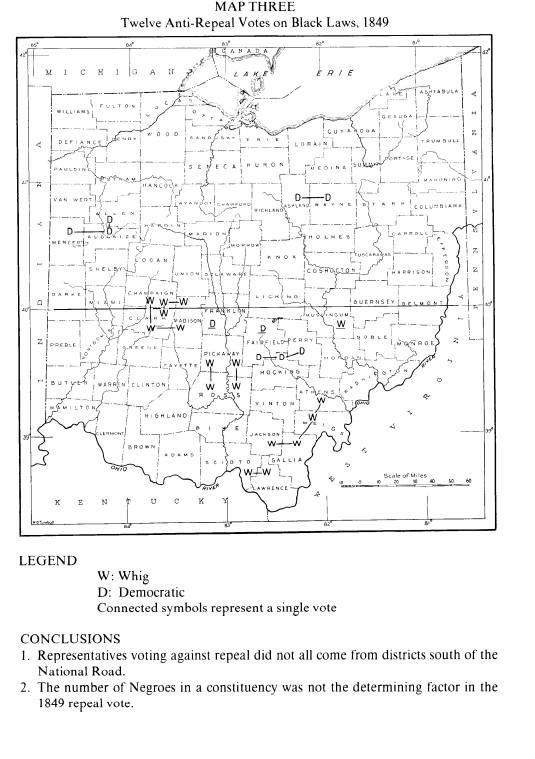

To determine where the hardcore

opposition to repeal was located, we should

look at Map III. It shows that for the

house vote on repeal in 1849 there were only

12 negative votes-7 Whigs and 5

Democrats-and that the anti-repeal votes were

not divided from those favorable by a

simple North-South separation; nor did they

have a direct correlation with density

of Negro population. Rather, most negative

votes were cast by representatives from

a narrow band of counties in west-central

33. Western Reserve Chronicle (Warren),

February 14, 1849; Daily Ohio State Journal (Columbus),

February 3, 1849; Ohio Statesman (Columbus),

February 2, 1849; Ohio, Senate Journal, 1848-49, p. 233,

250-251; Ohio, House Journal,

1848-49, pp. 251-253. By this legislation common school trustees could

establish separate schools, if they felt

it expedient, which would be under the jurisdiction of Negro direc-

tors, who would have access to local

taxes of blacks. Better than in 1848, this act required organization

of separate schools where Negroes were

denied admission to the regular common schools. Laws of Ohio,

1848-49, pp. 17-18.

34. Ohio, House Journal, 1848-49, pp.

15-16, 179; Ohio Statesman (Columbus), January 24, February

2, 1849; Adams County Democrat (West

Union), February 14, 1849; Cincinnati Enquirer, February 1,

1849.

|

174 OHIO HISTORY |

Black Laws Repeal 175

and south-southeastern Ohio, and there

were two votes from districts wholly north

of the National Road. The Whigs, judging

from the newspapers, were not vocal

one way or the other on the repeal

victory, but understandably some papers were

somewhat disturbed with Townshend and

Morse for their role in establishing Dem-

ocratic ascendancy in the house.35 For their part Free Soilers, after

congratulating

themselves for being a potent political

force, chastised the Whigs for their pre-

occupation with anti-Townshendism and

for their silence about the glorious event

of repeal. Some persons were unhappy

with the action of the Assembly, but such

discontent did not result in a

reenactment of the Black Laws.36

35. The Cleveland Herald raged:

"It would require an act of Omnipotence to bring Townshend up to

the level of a Judas Iscariot or a

Benedict Arnold, or Morse up to the level of a fool." Annals of Cleve-

land, XXXII (1849), item 1838.

In 1887 Whig Free Soiler A. G. Riddle

and Independent Norton Townshend exchanged views about

whether a deal with the Democrats had

been needed to secure repeal of the Black Laws. (See footnote 4

above) In light of the voting record of

the previous years, it is difficult to agree with Riddle (p. 350) that

the Democrats were ready for repeal by

1849. Chase stated flatly that a bargain was necessary to secure

repeal. Chase to Giddings, July 26,

1849, Roll 4, Giddings Papers. It would appear that the Cleveland

Plain Dealer was historically accurate when it wrote, "Had

Morse and Townshend merged themselves

with the Taylor Whigs . . . this measure

of repeal would have met the same opposition from democrats it

always has...." Cleveland Plain

Dealer, February 3, 1849.

36. Western Reserve Chronicle (Warren),

February 14, 21, 1849; Ohio Standard (Columbus), February

7, 1849; Anti-Slavery Bugle (Salem), August 25,

1849.