Ohio History Journal

GENERAL WILLIAM HULL AND HIS CRITICS

By M. M. QUAIFE

The Detroit campaign of 1812 lasted, in

all, but little over

two months (June 10-August 16); a

century and a quarter has

passed since its conclusion, during

which General William Hull's

countrymen have continued to load upon

him the heavy measure

of condemnation which was meted out to

him by his contemporary

associates and critics. This attitude has been perpetuated by

three generations of historians most of

whom have repeated the

chorus of contemporary condemnation.1 In

the writer's opinion

it is quite time to re-examine the

verdict which blasted Hull's

reputation and condemned him to a

shameful death. The recent

article of Prof. C. H. Cramer2 reflects, in a

general way, the

current condemnation of Hull's

leadership. This offering is in-

tended as a commentary upon Cramer's

presentation, in part, but

in a larger sense upon the entire body

of criticism of Hull,

whether voiced by Cramer or not.

That Hull was no military genius is, of

course, painfully

obvious; equally obvious is it that

there were no leaders of

Napoleonic character in the American

army in 1812. Had there

been, their talent would have been

wasted for lack of the public

spirit and governmental organization

essential to the successful

waging of military campaigns. Hull failed, in part because of

his own defective leadership; but in

larger part because of con-

ditions over which he had no control,

and which his contemporary

1 It

is somewhat noteworthy that Michigan historians, who might be presumed

to know the facts as well as any, have

been disposed on the whole to extenuate

Hull's failure. Among exemplars of this

attitude may be noted Judge Thomas M.

Cooley, Clarence Monroe Burton and

George B. Catlin. The Dictionary of American

Biography (New York, 1928-1937) article on Hull, the most recent

expression of

American historical scholarship on the

subject, after stating that Hull was found

guilty of cowardice and neglect of duty,

observes that "these charges would hardly

be sustained today." The author

adds that "his surrender without a battle was a

blow to American morale from which it

took nearly two years to recover." To the

present writer this statement seems

wholly without foundation.

2 C. H. Cramer, "Duncan McArthur:

the Military Phase," Ohio State Archaeo-

logical and Historical Society Quarterly

(Columbus), XLVI (1937), 128-47.

(168)

GENERAL WILLIAM HULL 169

critics were equally impotent to cope

with. This is not an attempt

to relieve Hull of the measure of

condemnation to which he is

justly liable but merely to indicate the

extent to which he has

been made a scapegoat for America's

shortcomings in the War

of 1812.

The more important criticisms which

Cramer's article in-

vites are two in number: Lack of

familiarity with the geography

of the Detroit River area, leading to

confused, or even unintel-

ligible, statements, and too ready

acceptance of contemporary

reports at their authors' own valuation,

without subjecting them

to the test of critical examination.

The geographical confusion is shared by

Cramer with a dis-

tinguished predecessor in the historical

field, for Francis Parkman

never understood his directions at

Detroit, although Robert

"Believe-it-or-not" Ripley

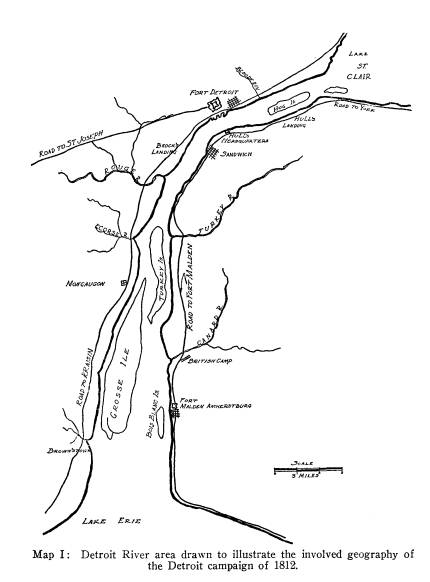

does. From Lake St. Clair to Sand-

wich (well below the Detroit of 1812) the river flows

from east

to west, instead of from north to south,

with the result that

Canada is here south of the United

States. Indeed, a century or

so ago present-day Windsor was called

South Detroit. At Sand-

wich the river turns southward in its

further course to Lake

Erie (14 or 15 miles distant). Confusion

over these simple

facts serves to render certain of

Cramer's statements unintelligible.

For example (p. 131),

"McArthur commanded the detachment

which successfully decoyed the enemy

south of the town," after

which he "hurried north . . . to

join the main American force."

The Pied Piper decoyed the rats of

Hamelin into the river, and

General Duncan McArthur must have done

as much for the

British army if he followed these

directions. Today, the vehicu-

lar tunnel runs south from

Detroit to Windsor, and north from

Windsor to Detroit. Obviously, McArthur

did not follow its

course; instead, he marched westward

from Detroit, along the

river bank, and having performed his

feint, returned eastward

through the town to rejoin the main

army, which crossed the

river at Belle Isle, landing in modern

Walkerville (more recently

incorporated in Greater Windsor).

A more significant geographical error is

evidenced on page

|

170 OHIO ARCHEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY |

|

|

GENERAL WILLIAM HULL 171

133, in dealing with Hull's final effort

to restore his line of com-

munication with distant Ohio. Apart from confusing

Captain

Henry Brush of Chillicothe with Major

Elijah Brush of Detroit,

commander of the Michigan Territorial

Militia, Cramer confuses

the operation he seeks to describe. Captain Henry Brush had

come northward (over the trail opened by

Hull) as far as Mon-

roe, bringing cattle and other supplies

for Hull's army. From

the Maumee to Detroit, the road skirted

the lakeshore and (farther

north) the river bank, passing through

the present down-river

suburbs of Trenton, Wyandotte, Ecorse,

and River Rouge. About

midway between Monroe and Detroit and

directly across the

river lies Amherstburg (frequently

called Malden), since 1796

the British military and administrative

center at the west end of

Lake Erie. The British and Indians knew

their local geography,

and early in August they put an

effective check upon Hull's

invasion of Canada by crossing the river

from Amherstburg to

Brownstown and occupying the roadway at

that point. By this

simple operation they effected the

complete isolation of Hull's

army from its government, and its base

of supplies in Ohio.

Until the road should be cleared and the

communication restored,

the army was a veritable "lost

battalion," and to this objective

Hull promptly bent his further

energies. Two efforts to open

the road to Monroe led to two battles

(Brownstown on August

5 and Monguagon on August 9) and two

complete failures.

Even before the issue of the second

effort, Hull withdrew the

army from Canada to Detroit, in the

night of August 7 and the

following morning. Following Monguagon,

General Isaac Brock

arrived at Amherstburg from Niagara, and

Hull, late on August

14, dispatched Colonels Lewis Cass and

McArthur, two of the

three militia colonels, with

approximately one-fourth of his entire

army, on a third effort to contact

Captain Brush.

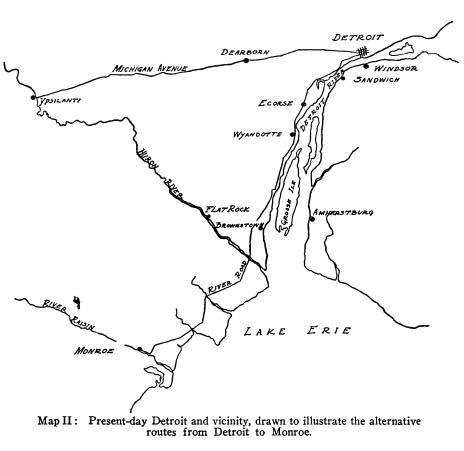

The ancient Indian trail from Detroit to

Fort St. Joseph ran

westward through Dearborn, Wayne, and

Ypsilanti, and at dif-

ferent times has been known as the Road

to St. Joseph, the

Sauk Trail, the Chicago Road, and U. S.

Highway No. 112.

Ypsilanti is on the Huron River, which

empties into Lake Erie

172

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

near Rockwood, a dozen miles north of

Monroe, and almost thirty

miles southwest of Detroit. It is also

eight or ten miles below

Brownstown, where the enemy lay athwart

the direct road from

Monroe to Detroit. Since two efforts to

drive him from it had

failed, it was now proposed to

circumvent him by sending Cass

and McArthur by the inland trail to

Ypsilanti, to which point

Captain Brush would proceed from Monroe;

from Ypsilanti, the

covering force would escort Brush, with

his supplies, back to

Detroit.

Although the trail to Ypsilanti had been

familiar to Detroiters

for more than a century, Cass and

McArthur made sad work of

following it, and even sadder work of

supplying an intelligible

report of their movements. To follow

Cramer, however, they

were sent out to relieve Captain Brush,

who had been "bottled

up" at Monroe. The term is

inaccurate, since nothing restrained

his freedom of movement save the

knowledge that if he moved

forward to Brownstown he would there

encounter the British.

"After advancing twenty-four

miles" Cass and McArthur found

themselves in a marsh and short of food,

and they now learned

of Hull's surrender to Brock. "With

the enemy in front and

famine in the rear," McArthur

(presumably, also, his associate,

Cass) was in a difficult situation. In

this dilemma manna de-

scended from heaven in the form of a

large ox, which the soldiers

joyfully barbecued. While thus engaged,

two British officers

appeared, with the articles of Hull's

capitulation. McArthur

thereupon surrendered to them,

"since a retreat to Fort Wayne"

(the nearest place where supplies could

be found) was out of

the question.

Professor Cramer's confusion is

sufficiently obvious; excuse

for it is found in the fact that the

reports he is following are

either purposely misleading or amazingly

careless of the truth.

The real movements of Cass and McArthur

on the critical fif-

teenth and sixteenth of August cannot

certainly be determined,

but Clarence Monroe Burton, whose

knowledge of Detroit local

history has never been excelled, has

arrived at an approximate

exposition of them. The detachment left

Detroit about sunset

GENERAL WILLIAM HULL 173

on the fourteenth, intent on contacting

Brush at Ypsilanti. If it

advanced twenty-four miles, it was far

beyond any possible inter-

ference from Brock on the sixteenth.

Instead, Burton shows3

that camp was made the first night

barely two miles from the

fort. On the fifteenth the detachment

advanced "slowly" until

evening, when the leaders (having

encountered no enemy) decided

to return to Detroit, and marching much

of the night, encamped

on the ground occupied the night

before. The morning of the

sixteenth, when Brock was crossing from

Sandwich to Spring

Wells, and the cannonading from Windsor

was proceeding, they

were within sight of the Detroit

stockade, but made no effort to

inform Hull of their presence or to

interfere with Brock, despite

the fact that a messenger had come from

Hull the night before,

expressly ordering them to return. Instead, they retreated to

the Rouge (perhaps three or four miles)

and were here engaged

roasting their ox while the surrender of

Detroit was taking place.

Enough, perhaps, has been said to

suggest that such criticism

of Hull as proceeds from the mouths of

Cass and McArthur

should be examined with care before

credence is given to it. It

is proposed here, however, to take a

somewhat wider view of

the campaign, and in its course to

examine more generally the

charges leveled against Hull. His first

and greatest mistake--the

one from which all later consequences

flowed--was his initial

decision to accept command of the army,

since as he had cor-

rectly pointed out to the Government,

Detroit was untenable by

any force which lacked naval command of

the lakes. The Gov-

ernment did nothing to achieve this

command, yet Hull foolishly

yielded to its persuasion that he assume

charge of the army de-

signed to hold Michigan and conquer

western Canada. The force

that was raised was primarily an

assemblage of adult males, rather

than an army. It consisted of the Fourth

U. S. Infantry, about

300 strong, and three regiments of Ohio

militia, 1,200 in all,

raised in the frontier fashion and

officered by local politicians,

who were about as innocent of military

skill as they were of a

knowledge of Sanscrit. Although the war

was popular in Ohio,

3 Clarence Monroe Burton, City of Detroit, Michigan,

1701-1922 (Chicago, 1922),

11, 1009-11.

174

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

neither privates nor officers had any

remote conception of disci-

pline, or any notion of submitting to

it.4 Before the

departure of

the army from Urbana a portion of the

militia defied their com-

mander, and were cowed into submission

only by Hull's firmness

in using his one regular regiment to

subdue them.

At the moment of invading Canada a

similar revolt occurred.

Hull had planned to cross the river in

the night of July 10, but

his project was defeated by some unruly

soldiers, who in defiance

of orders "kept constantly firing

off their pieces." Although the

militia were duly exhorted by their

officers "in the catching lan-

guage of sincerity" concerning the

necessity of invading Canada,

and the resultant glory to be gained

therefrom, a considerable

fraction of the army refused to leave

American soil.5 Exhibi-

tions of similar insubordination at

Niagara and elsewhere are

matters of common knowledge. Not so well

known, perhaps, is

the fact that General William Henry

Harrison, the most popular

leader the Northwest produced in the

war, was wholly unable in

1812 to control his soldiers. Upon the news of the Indian

siege

of Fort Wayne, the Ohioans swarmed to

the colors in such num-

bers that "every road to the

frontiers was crowded with un-

solicited volunteers."6 Their

zeal merely led to the consumption

of the supplies accumulated by Hull's

orders for the use of his

own army, for within ten days they

deserted the army en masse,

with Fort Wayne still unrelieved and

unseen, and not all the

eloquence employed by Harrison could

restrain them. Unlike

4 Professor Theodore Calvin Pease's

graphic characterization (Centennial History

of Illinois, II, 160-61) of the Illinois soldiers assembled to fight

Chief Black Hawk

in 1832 might well have been penned to

describe the Ohio soldiers of 1812. At

Stillman's River in 1832, 340 militiamen

were put to utter rout by Black Hawk

with only forty warriors. At Brownstown, on August 5, 1812, Major Thomas B.

Van Horn's 200 Ohioans were driven in

similar rout by Tecumseh with twenty-five

warriors. The numerical ratio is

identical in each instance--eight militiamen to one

Indian. At Brownstown six officers were

slain--one-third the total deaths suffered

by Van Horn. Hull supplies the reason:

The militia "ran away at the first fire and

left their officers to be

massacred." Report of the Trial of Brig. Gen. Wm. Hull

(New York, 1814), 66. The "Ohio

Volunteer," James Foster, was able to find

satisfaction in their nimble footwork,

observing: "Fortunately for Major Vanhorne,

a small portion of his detachment which

behaved in a rather cowardly manner, by

precipitantly retreating, prevented a

party of British and Indians, who were detached

for that purpose, from cutting off his

retreat." See his The Capitulation (Chillicothe,

1812), 56.

5 Hull puts the number at 180. Other

statements vary, but it is clear that the

true figure was distressingly large.

6 Moses Dawson, Narrative...of the

Civil and Military Services of Major Gen-

eral William Henry Harrison (Cincinnati, 1824), 288.

GENERAL WILLIAM HULL 175

Hull at Urbana, Harrison made no effort,

other than oratorical,

to control them.7

Not only was the army a stranger to

soldierly discipline, but

it was well-nigh criminally lacking in

ordinary material equipment.

The revolt at Urbana was occasioned by

the neglect to pay for

the clothing that had been promised. On

reaching Cincinnati,

on his way to join the army, Hull had

learned that the powder

supply was dangerously inadequate, and

the very guns supplied

the soldiers were in such deporable

condition that he was forced

to organize a company of artificers and

procure a traveling forge

with which to repair them while the

army was maching north-

ward to meet the enemy.

As for food, there was plenty in

southern Ohio, but the

problem of transporting it to feed the

army was one of appalling

dimensions. There was no road through

the Indian country

from Urbana northward, and permission

must first be gained

from the red men before Hull could even

begin cutting one.8

With 300 regulars and 1200 militia as

his army, Hull was ex-

pected to cut a road through the

northern Ohio wilderness; build

and garrison blockhouses to guard it;

maintain his 200-mile line

of communications, open all the way to

Indian or British attack,

and from Maumee Rapids onward to naval

attack, against which

he was helpless; to invade Canada,

despite the presence of British

armed vessels, and conquer it as far as

Niagara, at the opposite

end of Lake Erie.

He cut the road and brought his army to

Detroit, all things

7 McArthur's methods of enforcing

discipline were similar to Harrison's. Illus-

trative, is his conduct at a critical

moment in the Detroit campaign which affords

a unique addition to the literature of

military science. After the battle of Mon-

guagon on August 9, McArthur was sent

from Detroit with 100 men to bring in

the wounded. He was returning with them

in boats up the river, when his valiant

militiamen spied the British ship Hunter

across the river, which is here two or

more miles wide. Although the Hunter was

paying no attention to the boats, and

evidently had not seen them, the

militiamen immediately abandoned their helpless

charges and rushed madly for the protecting

forest. McArthur followed them and

not only stayed their flight, but

induced them to return to their post of duty. How

he accomplished it is thus related by

Foster, his admiring fellow-Ohioan: "He had

on board of his boat a cask, which

contained a few gallons of whiskey, with which

he told the men to fill their canteens

and invited them to drink freely; he related

to them the anecdote of an Indian, who

finding himself descending with rapidity to

the falls of Niagara, seized his bottle

of rum and drunk the contents ere he had

reached the dreadful precipice. In

this manner, the Col. encouraged his

men, and

without difficulty they reembarked."

8 Not until several years later was it

possible for one to journey from Detroit

to the adjoining United

States without trespassing on Indian territory.

176 OHIO

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

considered an extremely creditable feat.

From Detroit on July

12 he crossed the river unopposed, thanks to the operation

which

Cramer has described, and advanced a few

miles in the direction

of Amherstburg. Here the campaign

boggled down, and the

invasion ended, four weeks later, in the

withdrawal of the army

to Detroit. Although the commander of a

beaten army wastes

his time apologizing for his failure,

the historian may properly

examine the causes of it. Hull himself

gave several reasons for

his failure; among others, Henry

Dearborn's armistice which left

the British farther east free to

transfer their forces to Detroit;

the fall of Mackinac and the approach of

the "northern hordes"

of savages, avid to pillage and

massacre; the inability to maintain

his communication with Ohio, on which

the further existence of

his army depended. He did not mention,

of course, the cause

which his critics vociferously

emphasized, his own lack of bolder,

more aggressive leadership.

Ignoring, for the moment, both defense

and hostile criticisms,

the two compelling causes of Hull's

failure, before which all

other details pale to insignificance

are: he had been given a task

ludicrously beyond the possibility to

perform with the resources

at his command; and there was not a

responsible officer in his

army (the three Ohio colonels not

excepted) who possessed

enough military skill or knowledge to

lead it against the enemy.

The latter point is treated first. From

Hull's headquarters

in Windsor (still standing) to the River

Canard, the farthest

advance of the American force, is ten or

a dozen miles. From

July 12 to the night of August 7, Hull

maintained his head-

quarters at Windsor, meanwhile sending

out detachments of

troops repeatedly toward Malden. The

country is as level as a

table-top, and there were no defenses of

any kind, except Fort

Maiden itself. The Ohio political

colonels, Cass and McArthur,

led these expeditions (McArthur for

several days commanded

the entire army in Canada) and at the

Canard were within four

miles of Fort Malden. What (save their

own incompetence)

prevented them from going on and taking

the place? Let any

reader peruse the recital of James

Foster, a soldier under McAr-

|

GENERAL WILLIAM HULL 177 thur, or the journal of another soldier, and future governor, of Ohio, Robert Lucas, of these wearisome days, and conclude if he can that any of the Ohio militia officers were any better |

|

qualified to lead the army, or more eager to face the enemy, than the general they derided and conspired to overthrow. So far as Cass and McArthur (perhaps Hull's most influential critics) are concerned, their crowning demonstration of incapacity for ag- gressive leadership was afforded on their joint final expedition |

178 OHIO

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

of August 14 to 16. Ordered to Ypsilanti

to meet and convoy

Captain Brush, they abandoned the

mission, although unopposed;

returning to the vicinity of the town,

they calmly disregarded

Hull's order to rejoin him; with the

bombardment going on and

Brock crossing to the attack, they went

off in another direction

to the Rouge, where no enemy was, to

regale themselves upon

an unfortunate ox. Unlike brave Rowland

and Captain Brush

at Monroe, they neither fought nor made

any effort to escape.

If either Ohio colonel performed the

legendary act, discussed

by Cramer on page 134, of breaking his

sword in disgust over

the surrender, he had ample cause for

doing so; but a greater

degree of candor would have fixed the

object of his disgust nearer

home than the person of Hull.

It remains to note the regular army

lieutenant colonel, James

Miller, of subsequent text-book fame.

The regimental flag he lost

at Detroit is still preserved in London

as a military trophy. He dif-

fered from the Ohio colonels in at least

one important respect, for

when he found the enemy in sight he

possessed the will to fight.

Yet he failed as completely of attaining

the objective set him as did

all of Hull's other officers. To

Monguagon on August 9 he led

600 men, one-half of them his own (and

Hull's only) regular

regiment. He fought a good battle and

drove the enemy in flight

from the field of action. Instead,

however, of reaping the fruits

of victory by proceeding on to contact

Captain Brush at Monroe,

he halted in his tracks and presently

returned to Detroit. With

one-third to one-half the entire army,

and on the American side

of the river, he failed to open the line

to Monroe. His reasons?

--lack of provisions, personal illness,

the necessity of caring for

his wounded, and the difficult state of

the roads by reason of

recent rains. That these were not

compelling, is not denied. But

the pot, at least, should not call the

kettle black. If Miller,

entrusted with more than one-third of

the army, could not ad-

vance the twenty miles from Brownstown

to Monroe, even after

clearing the enemy from the way; if

McArthur and Cass, given

repeated opportunities, could not march

from the Canard to

Maiden, four miles away; or, unopposed,

the thirty miles from

GENERAL WILLIAM HULL 179

Detroit to Ypsilanti, when directly

ordered to do so; they, at

least, should not be too clamant in

condemning Hull for not

conquering all western Canada and

marching through hostile

country 250 miles to Niagara.

Let the activities of some of his

contemporaries who were

not condemned to death, but instead were

loaded with political

favors by their appreciative countrymen,

now be noted. After

his triumph of August 16, Brock left

Colonel Henry Procter

with a garrison of 250 men to hold

Detroit, while he himself

hurried eastward to glory and death at

Niagara. For over a year

Procter's single 41st Regiment, aided by

the Indian allies and

such Canadian militia as could be

mustered, held Detroit and the

Lake Erie front, despite every effort of

the Americans, with

vastly larger forces than Hull had

commanded, to dislodge them.

Twice during 1813 he carried the war to

the Maumee, where

Harrison maintained possession of Fort

Meigs only by desperate

efforts. For over a year, Harrison did not venture to send a

soldier north of the Maumee, although

the immediate objective

of all his operations was the recovery

of Detroit. In January,

1813, General James Winchester ventured

as far north as Monroe,

only to have his army entirely destroyed

by Procter; and Har-

rison, without awaiting the news of

Winchester's fate, made in-

decent haste to disclaim all military

and moral responsibility for

his venture. With marching and

counter-marching, the establish-

ment of bases and the later burning of

them in panic,9 the year

was filled with futile and in large part

aimless gestures in the

direction of Detroit; the operations as

a whole amounted to a

demonstration on a larger scale of that

inability to lead an army

9 Rev. Alfred Brunson was a soldier in

Harrison's army at Fort Seneca, at the

time of Procter's advance upon Fort

Stephenson. He relates that on hearing reports

of Procter's advance with "5000

regulars and 6000 Indians [the actual army may

have been one-tenth these numbers]"

Harrison hastily ordered Major George Croghan

to burn Fort Stephenson and join his

army at Fort Seneca, where Harrison himself

was in readiness to burn everything,

"provisions, stores, tents," and beat an instant

retreat. The order to Croghan

miscarried; he did not join Harrison the next morning,

and the latter must either hold his

ground at Fort Seneca or abandon Croghan's

little force to (as believed) certain

destruction. In this dilemma a "Council of

War" was held, to decide which

course to pursue. When Harrison asked for Cass's

opinion, the latter sagely observed that

it would be better not to retreat "till we

see something to retreat from," and

so the army remained, "to meet the enemy at

our breastworks... despite the odds in

numbers." Comment upon the state of mind

of the general, to whom the recovery of

the Northwest had been committed, seems

needless.

180

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

in the face of the enemy which had been

so painfully illustrated

by Hull, McArthur, and Cass between

Windsor and Amherst-

burg in the summer weeks of 1812. The one success

in a year

of campaigning was won by a twenty-one

year old boy, Major

George Croghan, at Fort Stephenson; and

for this brilliant

minor affair, Harrison could claim no

credit. After Oliver

Hazard Perry's victory of September 10

had given the Americans

that naval control of the lakes which

Hull two years before had

urged upon the Government as essential

to American success in

the Northwest, Harrison, strengthened by

fresh levies of a dozen

regiments from Kentucky, ventured for

the first time to advance

upon Detroit; for the British, the game

was up, and Procter's

little army promptly fled eastward, to

be overtaken and destroyed

in a despairing rear-guard action at the

Thames on October 5.

He who would know the shameful story of

the northwestern oper-

ations from Detroit in 1812 to the Thames in

1813 may find it

succinctly stated in Emory Upton's Military

Policy of the United

States, from which the following quotation is taken:

The cost of dispersing the 800 British

regulars, who from first to last

had made prisoners of Hull's army at

Detroit, let loose the northwestern

Indians, defeated and captured

Winchester's command at Frenchtown, be-

sieged the Northwestern Army at Fort

Meigs, and twice invaded Ohio . . .

teaches a lesson well worth the

attention of any statesman or financier.

Not counting the hastily organized and

half-filled regiments of regulars,

sent to the West, the records of the

Adjutant-General's Office show that

about 50,000 militia were called out in

1812 and 1813, from the states of

Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee, Pennsylvania,

and Virginia, for service against

Procter's command.10

If to save Ohio from conquest, and to

recover Detroit from

the grasp of the valiant British 41st

Regiment, required a year

of time, the service of 50,000 militia,

uncounted levies of regulars,

and a navy triumphant on Lake Erie, why

should Hull have

been pilloried for his failure to do far

more than this in a

few weeks, with 300 regulars, perhaps

1500 militia, and no navy

whatever? The answer rests largely in

the realm of psychology.

A certain faction of the American public

had stampeded the

Administration into declaring war

against Great Britain. The

measures taken for conquering the most

militant nation on earth

10 Emory Upton, Military Policy of the

United States (Washington, 1917), 111.

GENERAL WILLIAM HULL 181

were largely confined to the field of

oratory. In the West, where

alone the war was genuinely popular, it

was fondly anticipated

that Canada would fall into our hands

like an over-ripe apple.

Henry Clay, Kentucky's peerless orator,

voiced the general ex-

pectation when he affirmed that Kentucky

alone would conquer

Canada in a few weeks time. In such an

atmosphere of child-

like innocence, Hull's army of 300

soldiers and 1200 Ohio citi-

zens began the romp from Urbana which

was to continue to

Niagara, or even to Montreal. The

disillusionment produced by

Hull's surrender was exceedingly

painful. To blame others for

one's own stupidity and short-comings is

easy and ever popular.

A scapegoat must be found to appease the

angry multitude and

clear the skirts of the fatuous

politicians at Washington and the

make-believe soldiers of Ohio, and Hull

was offered up on the

altar of his country's folly. In three

years of warfare the Gov-

ernment enlisted 500,000 soldiers, as

many as the entire popula-

tion of Canada, and the end saw Canada

unconquered, the Capitol

and presidential residence in flames,

the country invaded and

within a hair's breadth of dismemberment

and national ruin.

It was Hull's peculiar misfortune to be

the first to reveal the

depths of the Nation's folly, and to

attract the cyclone of its

wrath. If he failed totally, or even

shamefully, it was not for

such blunderers as McArthur, of whom

even Professor Cramer's

friendly pen does not make much of a

military hero, to cast the

first stone. His final conclusion is

that "since McArthur never led

a large army in a vital campaign, the

story of what he might have

done remains within the realm of

conjecture." Possibly so. At

any rate, it is known he was proficient

at capturing an unguarded

flock of sheep, and an expert at writing

letters of resignation; the

measure of his statesmanship is

suggested by the fact that as late

as February, 1815, he had no conception

that the war had been

won, and was deliberately advising his

Government to depopulate

Detroit and make of western Canada and

Michigan Territory an

uninhabited desert.11

The nature of Hull's failure is better

disclosed by certain

11 Duncan McArthur to James Monroe,

Secretary of War, February 6, 1815.

182 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

general remarks of William Wood, Canada's historian of the

war, in comparing the opposing forces

of the two hostile nations,

than by all the accusations of his

contemporary critics:

"An armed mob must be very big

indeed before it has the

slightest chance against a small but

disciplined army." And "The

Americans [in the war] had more than

four times as many men.

The British had more than four times as

much discipline and

training."12

12 William Wood, The War with

the United States (Toronto, 1915), 20-22.