Ohio History Journal

A QUAKER SECTION OF THE UNDERGROUND

RAILROAD IN NORTHERN OHIO

BY PROFESSOR WILBUR H. SIEBERT,

of the Ohio State University

One of the main lines of the

Underground Railroad

which traversed Ohio from south to

north, began at

Ripley in Brown County on the Ohio

River and ran

through Highland, Fayette, Madison,

Franklin, Dela-

ware, Marion, Morrow, and Richland

counties to Green-

wich in Huron whence branches ran to

the lake north

through Erie County and northeast

through Lorain and

Cuyahoga counties. This line of slave

travel from Ken-

tucky had, of course, its switches and

loops and at fre-

quent intervals its short-line

connections with other

more or less parallel routes to the

east and west.

Early in December, 1926, General Edward

Orton

and the writer drove to the Alum Creek

Friends' Settle-

ment, or Marengo, in Peru Township,

Morrow County,

which was for many years an important

station for har-

boring fugitive slaves on the line

roughly traced above.

General Orton had his camera with him

and acted as

the official photographer of the

"expedition," taking pic-

tures of certain houses in the

settlement where fugitives

had been secreted until they could be

sent on to neigh-

boring stations on their way to Canada

and freedom.

The first settlers on Alum Creek were

Cyrus Bene-

dict, his wife, and their three

children, who removed

(479)

|

180 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications from Peru, New York, in the autumn of 1809, to Sun- bury, Ohio. There they lived on a rented farm for a little more than a year, when they bought land and built their cabin a half-mile northeast of South Woodbury. This was early in 1811. In the autumn of the next year they were followed by the aged parents of Cyrus, namely, Aaron and Elizabeth Benedict, and several of their sons and daughters. Aaron died three years later |

|

|

|

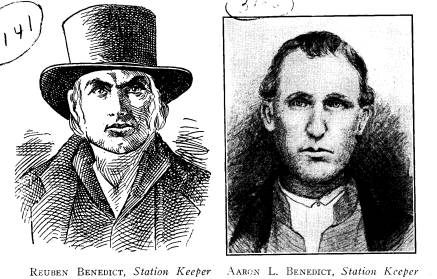

and his wife in 1821. A married son, Reuben, settled on the west side of Alum Creek a mile south of South Woodbury and lived there until his death in 1854. Another son, Aaron, and his family also settled on the west bank of the stream and there he died at the age of fifty-six years in 1825. Of the ten children of Aaron and Elizabeth a number did not come to Alum Creek until the War of 1812 was over. When Elizabeth died at the age of eighty she left one hundred and two de- |

Underground Railroad in Northern

Ohio 481

scendants living within sixteen miles

of her, besides two

daughters and their families who had

remained in Peru,

New York. Among the children of the

second Aaron

were Aaron L. Benedict and his sister,

Esther L., who

married Griffith Levering. Aaron L. had

a son, Livius

A., who was a mere lad in the early

1850's. Another

small boy of the settlement at that

time was Mordecai

J. Benedict, who was the son of Daniel

and was born

in 1845. There was also a third Aaron

Benedict who

was born in Alum Creek settlement in

1817, grew up

to be an abolitionist, engaged in

underground railroad-

ing, and risked his life several times

in assisting fugi-

tive slaves to gain their freedom. His

father's house

in the settlement was an underground

station. He died

in 1905 at the age of eighty-eight

years.

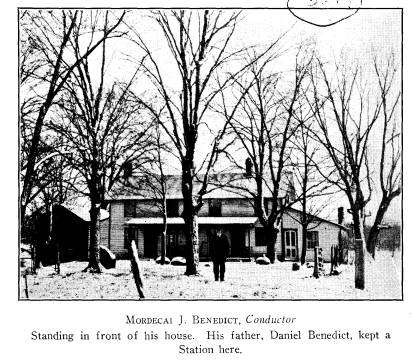

When General Orton and the writer

visited the set-

tlement in 1926 Mordecai was the only

member of it who

had personal recollections of the

fugitive slave days. He

was then a vigorous man eighty-one

years of age, dwelling

in a neat two-story frame house in

which he had lived as

a boy. He readily recalled having seen

the floors of the

sitting-and dining-rooms covered with

the forms of

sleeping Negroes when he came

downstairs of a morn-

ing, and he named various underground

stations to the

south and north of Marengo and the

prominent op-

erators of most of them. He also

produced a family

scrapbook containing newspaper

clippings and other local

memorabilia, including a clipping that

gave an account

of a station a few miles out of Marion,

Ohio, to which

slaves were sometimes conducted from

the Alum Creek

settlement. And, finally, he loaned the

writer a pamphlet

entitled The History of Peru

Township, Morrow

Vol. XXXIX--31.

482

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

County, Ohio, containing the "Early History of the Set-

tlement and Reminiscences by Aaron

Benedict and Oth-

ers," compiled by A. S. Benedict

and printed in 1897 by

the Sentinel Printing House of Mt.

Gilead, Ohio.

From these sources chiefly, the

following account and

incidents of the section of trunk line

of the Under-

ground Railroad extending from Columbus

to Lake

Erie have been derived.

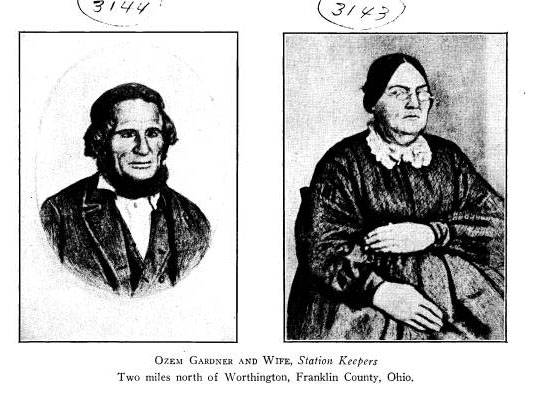

The route through the Alum Creek

settlement had

its initial station at Ripley on the

Ohio River and led

through numerous stations to Jason

Bull's place at Clin-

tonville, thence to Ozem Gardner's two

miles north of

Worthington, and so to Joseph Eaton's,

northeast of

Delaware, on or near the southern

boundary of Morrow

County. Mr. Eaton conducted the

fugitives through

the woods to Daniel Benedict's, the

southernmost house

of the Alum Creek settlement. A little

farther to the

northeast and off the main road was

Aaron Benedict's

house. He was active in caring for the

refugees, but

his wife was a Virginian and did not

relish the idea of

assisting in the escape

of southern chattels.

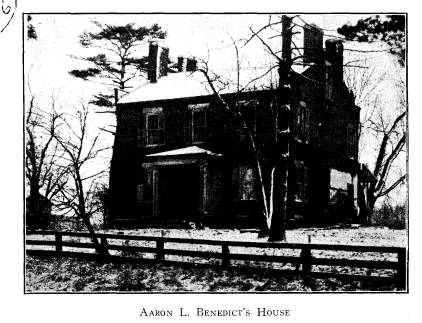

Sometimes a party of the runaways would

be taken to

the home of Aaron L. Benedict on the

main road. In

1857 he built a large brick house and

there continued

to receive underground passengers, but

in case of danger

he concealed them in a barn and

out-buildings across the

creek. A half-mile west of Aaron L.

lived his brother-

in-law, Griffith Levering, who disliked

to hide the fugi-

tives. But, nevertheless, under

pressure of pursuit, they

were put in his cellar, and he wisely

kept silent. Once

the danger was past, they would be

brought back to

Aaron L.'s place. East of Marengo was

Gardner Ben-

|

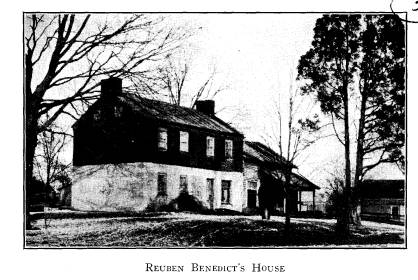

Underground Railroad in Northern Ohio 483 nett's farm. He also harbored fugitives in emergen- cies, although opposed to it under ordinary circum- stances. A mile farther north on the main road lived |

|

|

|

Reuben Benedict until his death in 1854. His conscience was clear about befriending liberty-loving Negroes, and he cared for them willingly. |

|

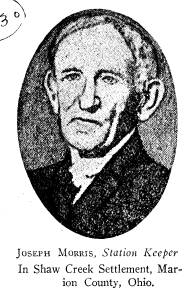

484 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications Nine miles farther north was the Mt. Gilead Friends' settlement. The principal station keeper of that locality was Joseph Mosher, who dwelt two miles south of the county seat. If, however, there was reason to suspect that slave-hunters were lying in wait north of Marengo, the conductors from that settlement drove northeast |

|

|

|

twenty miles with their passengers to the Owl Creek Friends' settlement, which was two miles north of Fred- ericktown in Knox County. There the operators were Asa and William Townsend, Ellis Willetts, and J. E. Lewis. They forwarded the fugitives to Mansfield, where the McClures, Benjamin, James, John, Samuel, and William, and other anti-slavery residents engaged in underground activities. On the regular Alum Creek |

|

Underground Railroad in Northern Ohio 485 route there was a way station northeast of Mt. Gilead, evidently at or near Lexington in Richland County, which connected with the Mansfield center. From Mansfield the direct route ran due north to Greenwich, another Quaker settlement, in the southeastern part of Huron County. The defiers of the Fugitive Slave Law at Greenwich were Willis R. Smith and his sons, who conveyed their passengers to Milan and so to Sandusky |

|

|

|

or to Huron on the lake shore, or by a northeastern branch to Oberlin, Berea, and Cleveland. At Cleveland, Huron, and Sandusky the refugees were put on board Lake Erie vessels bound for Canada. Mordecai J. Benedict, the son of Daniel, began driv- ing fugitives by the wagon-load in 1851, when he was only six years old. Sometimes a second wagon was re- quired, the driver being in many instances Mordecai's |

|

486 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications playmate, Livius, the son of Aaron L. Benedict. The trip they usually made was to Joseph Morris's house by a branch emergency line running to the Shaw Creek Friends' settlement, about nine miles southeast of Ma- rion. In external appearance the Morris house was an unpretentious two-story frame dwelling with gable |

|

|

|

ends and a portico. It stood, and still stands, on the Canaan pike in Richland Township, and was a haven for hundreds of fugitive slaves. Its owner, a well- known Quaker philanthropist in his day, had spared no pains to make it a safe refuge for them. In the low attic and in the cellar he had built false partitions to provide |

|

Underground Railroad in Northern Ohio 487 secret chambers for his swarthy guests. A reporter of the Marion newspaper, The Press, who visited the place in October, 1900, writes that the garret was a carefully constructed labyrinth and that the cellar had two secret rooms, each capable of serving as a secure hiding-place for a dozen refugees. These rooms were hidden by large cupboards fastened to their doors. From the cel- |

|

|

lar two tunnels led out, one to the barn and the other to the corn-crib. These passages were concealed in the same manner as the secret chambers and af- forded safe egress from the house when it was surrounded by slave-hunters. It is said that in several instances Ne- groes made good their escape while their owners were on guard outside the house. Joseph Morris not only kept a rendezvous for fugitives dur- ing the anti-slavery days, but also aided escaping slaves dur- |

|

ing the Civil War. During the Virginia campaigns he was with the Union forces, giving assistance to the wounded and distressed. He rendered like service dur- ing the great fire in Chicago and became widely known for his good deeds and his charities. Tributes of appre- ciation are said to have come to him from Presidents Grant and Harrison. He celebrated his ninety-fifth birthday on June 23, 1899, and died soon after. His house was probably the safest retreat for fugitives in |

488 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

northern Ohio. It received loads of

passengers not only

from the Marengo Friends' settlement,

but also from

the Olentangy River and doubtless more

western routes,

some of which issued from Cincinnati.

Mr. Morris for-

warded some of his numerous charges by

intermediate

stations to the Friends' settlement at

Adrian, Michigan,

whence they were carried to station

keepers at Detroit

and sent across the river to Windsor, Ontario.

It is evi-

dent from the above account that most

of the under-

ground operators on the Marengo line

and the routes

and branches with which it was

connected were Quakers.

The following incidents will show

something of the

methods of the operators of the

underground system at

Marengo and similar stations. In 1835 a

slave-owner,

on his way from West Virginia to

Missouri, camped on

the bank of the Scioto River near

Franklinton. He was

accompanied by four slaves, a mother

and her threee

children. They were abducted and hidden

away by col-

ored citizens of Columbus, who soon

conducted them to

Ozem Gardner's farm, twelve miles north

of the city.

Mr. Gardner took them to Daniel

Benedict's house at

Alum Creek settlement, where they

remained several

days. The master and two hired helpers

were able to

trace them to the settlement, found two

of the slave boys

in Daniel's yard, and started away with

them. As quar-

terly meeting was in session at

Marengo, Daniel Bene-

dict was entertaining some visiting

Quakers from Lo-

gan County. Daniel and his guests

halted the slave-

catchers at the gate and sent to the

meeting-house for

help. They also summoned Barton

Whipple, a justice

of the peace, who read the law on

kidnapping to the

slave-owner and the large group of

Friends that had

|

(489) |

|

490 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications assembled. After hearing about the heavy fine pre- scribed in the law for attempting to convey colored per- sons out of the state without proving property, the two hirelings fled through the woods. After some parley with the slave-owner, Daniel Benedict informed him that if he would leave, first promising not to molest the mother and children thereafter, the law would not be |

|

|

|

enforced against him. Accordingly, he went away. It was later reported in Marengo that one of the hirelings said that he "didn't know where all those Quakers came from, unless they came out of the ground." The next incident involves an abduction of a wife and two children from Kentucky by their slave husband and father, and a subsequent reclamation of the woman and her children by their owner. In 1837 a young col- ored man, Elisha Young by name, came to the Alum |

|

Underground Railroad in Northern Ohio 491 Creek settlement from Kentucky. His name was promptly changed to John Green. He had left in slav- ery a wife and two small children, whom he decided to rescue. Aaron Benedict hired him and promised to help him in bringing his family north. They set out with a |

|

|

|

team and carriage in the early autumn and drove to Rip- ley on the Ohio River, traveling by night for the most part. At Ripley they stopped with the Rev. John Ran- kin, one of the most noted abolitionists on the river. Mr. Rankin took Green across to the Kentucky shore in a rowboat under the cover of darkness and instructed him to burn a signal light at a certain spot on his return. |

|

|

|

(492) |

Underground Railroad in Northern

Ohio 493

The Rankin house on the hill at Ripley

was a much-

patronized station of the Underground

Railroad for

many years before the Civil War, and

was continually

receiving fugitives from across the

river, sometimes by

pre-arrangement with operators on the

other side.

About a fortnight later, Green

returned, with his fam-

ily, from a sixty-mile trip into

Kentucky, and made his

signal as agreed upon. Mr. Rankin and

Aaron Benedict

rowed across the river and brought them

back. On the

following night Mr. Benedict and his

party started

northward and in due course by night

journeys, their

days being spent with friends along the

way, arrived at

Marengo. Green and his family remained

in the settle-

ment, occupying a cabin not far from

the place of his

employer, Aaron Benedict.

About six weeks later several men

arrived in a

wagon from Delaware late at night,

entered the cabin,

took the woman and children from their

beds, and drove

off with them. Green at the time was

not at home, be-

ing in the woods with Mordecai J.

Benedict hunting for

raccoon. They were summoned by the

blowing of a

horn and emerged only in time to hear

the wagon being

driven rapidly away. It returned to

Delaware. Mor-

decai and Green soon followed on

horseback, obtained

a warrant after some delay, but failed

to find the sheriff.

At length they secured the services of

a constable near

Bellepoint on the Scioto River and

followed the kidnap-

pers to West Jefferson on the National

Road, fourteen

miles west of Columbus, where they were

found drink-

ing in a tavern. The constable would

neither serve the

warrant nor surrender it, and Mordecai

and Green could

do nothing but return home. It was no

longer safe for

494

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

the Negro to stay at Marengo and he

soon took passage

on the Underground Railroad for Canada.

Later he

married there, having heard that his

wife had died in

Kentucky two years after her capture.

After the Civil

War Green returned and lived for a

brief time in Ash-

ley

He then went to Kentucky and brought back with

him a daughter and her husband. They

settled in Van

Wert County.

The following incident is concerned

with an exciting

rescue and the transportation of the

refugee to Canada

by the Underground Railroad. In 1838 a

Negro ran

away from his master at the Kanawha

Salt Works in

West Virginia and arrived at Marion,

Ohio, where he

became the hostler in a stable

connected with a tavern.

He was soon recognized by some one from

his old

neighborhood, who informed on him. The

master came,

had him put in jail, and returned home

to obtain wit-

nesses to prove his property. The

fugitive was kept in

prison forty days. Shortly before his

trial the sheriff's

wife, who had previously lived in or

near the Alum Creek

settlement, sent word to the Quakers of

the approach-

ing hearing. Nine of them went to

Marion, of whom

one was admitted to see the prisoner.

In the conversa-

tion between the two it was revealed

that the master

had come back, bringing six witnesses

with him and

that three of them had been owners of

the prisoner.

One was a lawyer (a Mr. Goshorn), who

had come to

assist in recovering the slave.

The Quakers conferred together and

decided to re-

sort to strategy. They also took into

their confidence a

Negro who had tried to liberate the

prisoner by under-

mining the jail. Their plan was to have

the Negro and

Underground Railroad in Northern

Ohio 495

the prisoner make a dash from the court

room as soon

as the judge had rendered his decision,

run through a

neighboring corn field, and make their

escape on fast

horses that would be in waiting for

them. The Quakers

were to block the stairway and thus

prevent pursuit.

The next day the prisoner was given his

hearing, the

witnesses testified, and bills of sale

were produced show-

ing that the slave had passed through

the hands of

several masters, being finally acquired

by John Smith,

the claimant. However, Judge Bowen

remanded the

prisoner to jail, and postponed his

decision until the

following morning. That evening one of

the Quakers

visited the prisoner and gave him full

instructions.

In giving his decision, Judge Bowen

called attention

to the fact that one of the bills of

sale designated John

Smith as the owner while the witnesses

had testified

that Mr. Smith was the owner. The judge

maintained

that these might be two different

persons and therefore

decided in favor of the prisoner.

Nevertheless, the

master seized hold of his slave,

flourished his bowie-

knife, and declared that he would have

his nigger if he

had to go to hell or Canada after him.

A rush and

scramble followed. The slave had hold

of the arm of

one of the Quakers, from which the

master could not

disengage him, while the Southerners

brandished their

pistols, knives, and clubs. Thus they

reached the street.

The sheriff called out the militia, who

succeeded in

shutting the Negro into a building,

although the door

was promptly battered in by the

attacking party. How-

ever, the fugitive and his colored

friend fled from the

rear end of the building, while the

Quakers and West

Virginians were indulging in a

scrimmage in the front.

496

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

One of the Quakers passed through the

corn field and

awaited the coming of the two colored

men. When

they arrived they mounted the horses

provided for

them and were told where to meet their

friend. They

reached Alum Creek settlement the same

night. A few

nights later the rescued Negro was

accompanied by

Aaron L. Benedict, Griffith Levering,

and one of their

neighbors to the Owl Creek Friends

settlement, two

miles north of Fredericktown, and after

a day's rest,

they proceeded to Greenwich in Huron

County, which

was another Quaker settlement. Thence

they passed on

the next night to Oberlin, where the

refugee was placed

in safe hands. He soon landed in

Canada.

The following incident is one in which

the master

of escaped slaves and a deputy United

States marshal

were tricked into imprisoning the wrong

persons. It was

shortly after the Fugitive Slave Law

was enacted in 1850

that three Underground passengers came

to a station at

Sunbury, Ohio, late in the afternoon,

and were hidden

away. At dusk their master with a

search-warrant

and a deputy United States marshal

arrived in the

place and by chance or otherwise

questioned the keeper

of the station. He unhesitatingly

admitted that he had

seen that afternoon the three fellows

described to him,

and said that he knew a man who

secreted runaway

slaves. He suggested that the master

and the marshal

put up at the tavern and keep their

business secret until

he had tried to find the fugitives. The

slave-hunters

complied with the advice given them,

while the station

keeper made good use of the time thus

afforded him to

forward the Negroes by rapid stages. He

also decided

to play a practical joke on the

intruders by getting

Underground Railroad in Northern

Ohio 497

three of his anti-slavery friends to

blacken their faces

and hands and occupy a stable near the

jail. It was now

dark, and the station keeper went to

the tavern and

led the slavehunters to the house of a

man who, he

said, had seen three black men enter

the stable. Several

visitors were at this man's house,

presumably to see the

fun. They all went to the stable, the

supposed fugi-

tives were apprehended by the deputy marshal,

and

placed in jail, the master claiming

them as his property.

Early in the morning the deputy marshal

and gratified

owner made their appearance to get the

chattels. The

jailer kindly brought a basin of water

for them to wash

their faces and hands in, and they

emerged from their

cell white men, to the marked

discomfiture of the claim-

ant and his companion. Although the

Southerner at

once disclaimed ownership of the

released prisoners,

he was warned that he had laid himself

liable to arrest

by causing the imprisonment of these

white citizens.

The warning had the desired effect of

hastening the

departure of the master and the

marshal.

About the time of the last incident

another ruse was

practiced on two masters who, with a

warrant and a

deputy marshal had pursued their eight

slaves, men,

women and children, as far as Oberlin

and then had

passed to a place beyond where

slave-owners were ac-

customed to lie in wait for their

runaways. These

slaves had been forwarded from the Alum

Creek set-

tlement. The anti-slavery men of

Oberlin understood

the situation, and were anxious to get

the fugitives out

of danger. They therefore took eight

free negroes who

tallied pretty well with the

description of the runa-

ways, and conveyed them by wagon to the

masters'

Vol. XXXIX-32.

498

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

waiting place. The deputy marshal

apprehended the

Negroes and put them in jail. Meantime,

the real fugi-

tives were sent by the same route to

Milan in the wagon-

bed underneath a load of hay, and so

probably to Huron.

On his return in the morning the driver

informed the

marshal that he had seen eight Negroes

depart by ves-

sel for Canada that morning.

Another instance of the outwitting of

pursuers oc-

curred near Seville in the southern

part of Medina

County, on the farm of Halsey Hurlburt,

who is de-

scribed as an abolitionist of the

Joshua R. Giddings

school. In May, 1852, a Negro, his

wife, and their

three boys were brought to Hurlburt's

house. As the

man was the property of one master and

the woman

and children, of another, they had made

their escape

and come by the Underground Railroad to

Hurlburt's.

They had spent but a single night there

when the two

masters, a deputy United States

marshal, and the

sheriff and his posse surrounded the

house and de-

manded admission. While Mr. Hurlburt

parleyed with

them his daughter Julia led the slaves

through the cellar

and by way of a corn field and piece of

woods to a

swamp near Chippewa Lake. Thence they

were able

to reach a small island and take up

their abode in a

hunter's cabin thereon. There they were

kept and fed

until all danger was past. They were

then sent in a

skiff up the lake to a place near the

Milan road, placed

in a covered wagon and carried to Milan,

where they

were put in charge of the captain of a

vessel friendly

to fugitives, sailed down the Huron

River and across

Lake Erie to the shore of Ontario. Mrs.

Hurlburt had

supplied girls' clothes for the boys

and men's garments

Underground Railroad in Northern

Ohio 499

for the women. As the steamboat was

about ready to

leave for Canada the master and an

officer came on

board, but through the shrewdness of

the captain were

unable to discover the objects of their

search. As the

vessel approached Maiden the captain

put his colored

passengers into a small boat and had

them landed on

the Canadian shore. This was a common

occurrence

in anti-slavery days, for the

underground system main-

tained its lake traffic and could

entrust its passengers to

the captains of a goodly number of the

vessels plying

on Lake Erie.

'Squire Hull skillfully threw a

slave-owner off the

scent at his farm seven miles west of

Delaware near

the Scioto River. While a slave woman

and her three

children were stopping at his house he

learned that

their master, provided with a warrant,

was looking for

them in the neighborhood. He put them

under the

floor of his barn, spread wheat in the

straw on the

floor, and set his horses to tramping

it out to prevent

the voices of the children being heard.

The master

came and searched the premises in vain.

After he had

departed the 'squire took the fugitives

to the Alum

Creek settlement. Passengers arriving at the Hull

farm

appear to have come usually from

Marysville,

which was connected with stations at

Mechanicsburg,

Urbana, Springfield, and places farther

south. 'Squire

Hull frequently drove them to the Alum

Creek settle-

ment, a distance of about twenty-five

miles. He was

afterwards president of a bank at

Bucyrus.

Some of the cruel features of slavery

are exhibited

in the following incidents. About 1850

an old colored

man and his wife were brought to Daniel

Benedict's

500

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

house at Marengo. They had belonged to

a kind mas-

ter in Kentucky, but at his death had

been sold with

his other slaves to a trader in

Louisiana, who sold them

in turn to a sugar-planter. Their new

master was so

cruel in his treatment of them that

they fled to a cane-

brake. Bloodhounds were set on their

trail and so man-

gled the woman's limbs that she was

unable to travel

for two months. At length they made their

way back

to Kentucky, were concealed by

relatives and friends,

and conveyed by them across the Ohio

River. Thence

they traveled by the Underground

Railroad, stopped at

the Alum Creek settlement, and were

sent on their way

to Canada. On their long journey from

Louisiana to

Kentucky they experienced many

hardships, privations,

and hairbreadth escapes.

One traveler who came to the

settlement, was a

young mulatto who rode his master's

race-horses as a

jockey. In fact, he had one of the

horses with him,

on which he had escaped from

Chillicothe, where his

master was attending a race. The slave

was well

treated, except when he failed to win a

race. Then he

was severely whipped. He made up his

mind to stand

such abuse no longer and to flee the

next time they were

on Ohio soil. At Chillicothe his

master's horse won in

nearly every heat, and its owner

indulged himself in a

spree in his hotel room. The jockey

provided himself

with false whiskers cut from a black

sheepskin, put his

master to bed in a sodden condition and

donned his

clothes, took the race-horse from its

stable, and started

for Canada. With the help of

Underground station

keepers he reached the Alum Creek settlement, and

after a short stay went through safely.

Underground Railroad in Northern

Ohio 501

It has been affirmed by a former

Underground op-

erator at Marengo that Eliza and her

child, the famous

characters in Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle

Tom's

Cabin, came there after the young mother's thrilling

adventure in crossing the Ohio River to

Ripley on float-

ing cakes of ice with her infant in her

arms. He also

said that she undertook the hazardous

adventure in

order to avoid the pangs of separation

from her child,

which had been sold to a slave-trader by

her master,

and added that they were sent safely on

to Canada.

The number of station keepers in the

Alum Creek

settlement was six at least and

probably nine or ten.

One of these, Daniel Osborn, kept a

record of the num-

ber of fugitives received by him during

five months,

namely, from April 14 to September 10,

1844 (for the

facsimile of this record see the

writer's volume entitled

The Underground Railroad, pp. 344-345). It amounted

to forty-five. Most of these fugitives

were from Ken-

tucky, but two colored boys were from

Virginia. Un-

der date of August 16 Daniel notes that

a colored man

had gone from Gilead (probably Mt.

Gilead) back to

Kentucky and returned with his wife and

child and

his wife's sister. Eight days later he

records that a

colored woman, who had been to Canada,

returned to

the same state and brought back four of

her children

and one grandchild. The last item of

the memorandum

is dated September 10 and is to the

effect that a yellow

man from Kentucky had been caught near

Cratty's

house and carried back to slavery. It

seems likely that

during this period of five months all

the station keepers

in the Friends' settlement on Alum

Creek had cared

for not less than two hundred runaway

Negroes. The

|

502 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications writer was told on a visit to the settlement that the en- actment of the stringent Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 did not check travel on the Underground Railroad, but on the centrary increased it. For example, during a single month in the year 1854 or 1855, Aaron L. Ben- edict had as many as sixty fugitives at his house and on one occasion twenty at dinner. The statements of numerous station keepers from various northern states corroborates the above testimony as to the effect of the Fugitive Slave Act on underground passenger traffic after 1850. The slaveholders were well aware of the fact, and the widespread disregard of the provisions of the Act in the North was an important reason for their trying to withdraw from the Union. The Quaker set- tlements in Ohio certainly had their share in bringing about that situation. |

|

|