Ohio History Journal

SENECA JOHN, INDIAN CHIEF

HIS TRAGIC DEATH

ERECTION OF MONUMENT TO HIS MEMORY

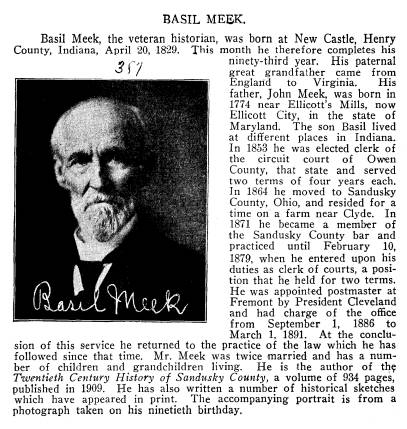

COMPILED BY BASIL MEEK

SENECA JOHN

Not much is known pertaining to the

direct biog-

raphy of Seneca John. The most that we

have is inci-

dental to and related in the story of

his execution. He

belonged however to a prominent family

of his tribe

and was one of four brothers, or rather

of three full

brothers named Comstock, Steel and

Coonstick and him-

self a half brother of the three named.

Comstock was a principal chief of his

tribe. Seneca

John succeeded Comstock as chief and

Coonstick suc-

ceeded Seneca John, or became a chief

after Seneca

John's death. Thus it appears that the

family furnished

three chiefs of the tribe.

From the story mentioned, we find that

Seneca John

was a tall noble looking man, and

resembled Henry

Clay of Kentucky; and like Clay was

very eloquent as

a speaker - the most eloquent of his

tribe. If ill feel-

ing arose in the councils he could by

his eloquence and

persuasive powers of speech restore

harmony. He was

very amiable and agreeable in his

manners and cheerful

in disposition. These traits combined

made him popu-

lar with his tribe, and upon the death

of Comstock he

was made a chief. His credit at the Trading Post at

Lower Sandusky was of the highest, and

he often be-

(128)

|

Seneca John, Indian Chief 129 |

|

|

|

Vol. XXXI-9. |

130

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

came security for the more improvident

members of his

tribe. He was peace loving, but by

reason of his high

qualities and popularity he was the

victim of jealousy

and envy on the part of his brothers,

which finally

resulted in his tragic death, near the

spot where the

monument erected to his memory stands.

During an expedition by his half

brothers Steel and

Coonstick, in the West hunting,

trapping and looking

for a new home for the tribe, lasting

about three years,

Chief Comstock died. On their return in 1828, they

found Seneca John chief in charge of

the tribe as the

successor of Comstock. This so aroused

their jealousy

and excited their envy that they

determined to make

away with him, and accordingly

preferred the false

charge against him of causing the death

of Comstock by

witchcraft. According to the belief of

the Senecas, the

superstition of witchcraft was to them

a verity, a

magical or supernatural power, by

agreement, with evil

spirits, the possessor of which could

bring calamity upon

or even death of the victim. The

penalty for its practice

was death. Seneca John, being innocent

of any wrong

in the death of Comstock, denied the

charge, in a strain

of pathos and eloquence rarely

equalled, in expressions

of love for Comstock and grief over his

death, but with-

out avail He was condemned to die, and

was killed by

his brothers accordingly, in the month

of August, 1828,

under the semblance of the execution of

a judicial sen-

tence, and was buried with Indian

ceremonies not more

than twenty feet from where he fell.

Sardis Birchard, cited in Knapp's

History, remem-

bered the death of Seneca John. He said:

Seneca John, Indian Chief 131

"The whole tribe seemed to be in

town the evening before

his execution. John stood by me on the porch of my

store, as

the other Indians rode away. He looked at them with so

much

sadness in his face, that it attracted my attention

and I wondered

at John's letting them go away without

him. He inquired of

me the amount of his indebtedness at my

store. The amount

was given. He bade me good-bye, and

went away without relat-

ing any of the trouble.

"Chiefs Hard Hickory and Tall

Chief came into town the

day of the killing of John, or the next

day, and told me about

it. Tall Chief always settled the debts

of Indians who died-

believing they could not enter the good

hunting ground of the

spirit land until their debts were

paid. He settled the bill of

Seneca John, after his death."*

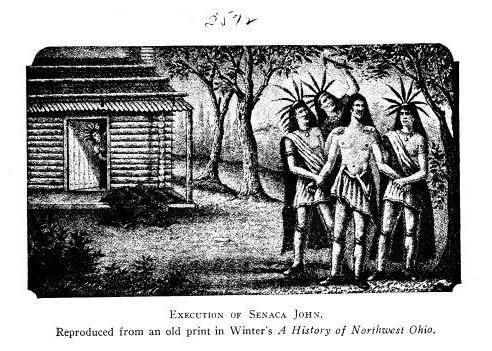

THE EXECUTION

The particulars of the tragedy as

related by an In-

dian chief, named Hard Hickory by whose

cabin it was

enacted, and who was present are

substantially as fol-

lows:

His brothers pronounced him guilty and

declared

their determination to become his

executioners. John

replied that he was willing to die, and

only wished to

live until next morning to see the sun

rise once more.

This request being granted, John told

them that he

would sleep that night on Hard

Hickory's porch, which

fronted the East, where they would find

him at sunrise.

He chose that place, because he did not

wish to be killed

in the presence of his wife, and

desired that the Chief

Hard Hickory witness that he died like

a man.

Coonstick and Steel retired for the

night to an old

cabin nearby. In the morning in company

with Shane,

another Indian, they proceeded to the

house of Hard

Hickory - who was informant - who

stated that a

little after sunrise, he heard their

footsteps on the porch,

*This quotation is a paraphrase, in

part, of the reminiscences of

Sardis Birchard recorded in Knapp's History

of the Maumee Valley.

|

(132) |

Seneca John, Indian Chief 133

and he opened the door just wide enough

to peep out.

He saw John asleep on his blanket and

them standing

near him. At length one of them woke

him and he

immediately rose, took off a large

handkerchief which

was around his head, letting his

unusually long hair fall

upon his shoulders. This being done, he

looked around

upon the landscape and upon the rising

sun, to take a

farewell look of a scene he was never

again to behold;

and then announced to his brothers that

he was ready

to die. Shane and Coonstick each took

him by the arm

and Steel walked behind him. In this

way they led him

about ten steps from the porch when his

brother Steel

struck him with a tomahawk on the back

of his head,

and he fell to the ground bleeding

freely. Supposing

the blow sufficient to kill him, they

dragged him under a

peach tree nearby. In a short time he

revived however,

the blow having been broken by his

great mass of hair.

Knowing that it was Steel that struck

him, John as he

lay, turned his head toward Coonstick

and said "Now,

brother, take your revenge."

This so operated on Coon

stick that he interposed to save him;

but the proposition

enraged Steel to such an extent that he

drew his knife

and cut John's throat from ear to ear;

and the next day

he was buried with the usual Indian

ceremonies near

the spot where he fell as before

stated, and his grave

was surrounded by a small picket fence,

which three

years later was removed by Coonstick

and Steel.

THE MONUMENT

The monument erected by the Sandusky

County

Pioneer and Historical Association, was

unveiled with

interesting ceremonies July 4,

1921. It is placed by

134

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

the east side of the public road, west

of and near the

spot where Seneca John was executed and

where he was

buried, being the site of Chief Hard

Hickory's cabin

and of the present residence of Edwin

Young, about one

and a half miles north from the village

of Greenspring.

It consists of a boulder of unique

shape, being flat in

front and rear surfaces, unlike most of

its sort, which

are rounded in form. It is thirty-six inches in height,

thirty inches in width, and twenty-four

inches thick at

the base, gradually becoming thinner

toward the top.

It is granite in formation, with one

edge or side a pebble

conglomerate the entire height of the

stone. It stands

firmly set on a concrete base. The inscription is as

follows:

SENECA INDIAN

RESERVATION

SENECA JOHN

NOTED CHIEF

WAS EXECUTED

NEAR THIS SPOT, EASTERLY

BY HIS TRIBE IN

1828

CHARGED WITH WITCHCRAFT

NORTH 30 RODS IS THE NORTH BOUNDARY

OF THE RESERVATION.

ERECTED BY THE SANDUSKY COUNTY

PIONEER & HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

- 1921 -

Seneca John, Indian Chief 135

THE SENECAS

The Seneca Indians, occupying what was

known as

the Seneca Reservation described below,

of whom

Seneca John was a prominent Chief, as

noted above,

were offshoots of the old Seneca

Nation, one of those

comprising the once noted Iroquois

Confederacy in the

State of New York, east of the Niagara

River, called the

Five Nations. They were often spoken of as the

"Senecas of Sandusky,"

located as they were along the

Sandusky River and vicinity. Mingled

with them were

wandering remnants of other

tribes. All these had

occupied this region for very many

years prior to the

date of the reservation, probably ever

since the extermi-

nation of the former occupants, the

Erie Nation, by the

Five Nations about the middle of the

seventeenth cen-

tury. It is quite probable that in the

wars against the

Eries, portions of the Senecas, and

perhaps of other

tribes, of the Five Nations, finding

this a "goodly land"

in which to dwell, remained permanently,

thus becoming

the progenitors of the Senecas of the

reservation. It

was an ideal land and home for them.

The beautiful

Sandusky River was then navigable for

canoes all the

year round. The river teemed with fish, the marshes

were alive with wild fowl, and the

forests abounded with

large game. It was, indeed, suggestive

and emblematic

of their hoped for happy hunting ground

in the land of

the hereafter, in which they believed

and expected to

gain.

In their intercourse with the whites they were

friendly, but drunken quarrels and

fatal jealousies not

infrequently disturbed the peace among

themselves. It

was unlawful to furnish them with

intoxicating liquors,

but the law was violated by the whites,

as indicated by

136

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

the return of indictments against

several parties at the

first term of the Common Pleas Court

(1820) for selling

intoxicating liquor to Indians. They lived in the vil-

lages throughout the reservation, but

their head-

quarters, or seat of government was in

Sandusky

County about two miles northwest from

the site of

Greenspring village. Their council

house in which all

matters concerning the administration

of their govern-

ment by the chiefs and head men were

held, was located

not far from the place where the

monument just erected

stands. Trials for offenses committed

were here held,

and punishments meted out to the

guilty. For murder

and witchcraft the penalty was death. Execution

of the

death sentence was carried into effect

by the nearest of

kin, to the person against whom the

crime had been com-

mitted. The similar provision in the

Hebrew criminal

code is believed by some authorities a

suggestion of

the Semitic racial origin of the

Senecas as probably

descended from one of the lost tribes

of Israel. Their

principal burying ground was in what is

now Ballville

Township in Sandusky County.

While the U. S. Government claimed and

exercised

ultimate sovereignty over all

reservations, it conceded

and allowed complete personal

independence to the indi-

vidual occupants, and complete

municipal or civil juris-

diction to the tribes in all matters

pertaining to their

own manners, customs and laws,

including punishment

for crimes and offenses against

them. They were in

respect to these matters an independent

sovereignty, or

power. This was clearly recognized by

the Judges of

the Supreme Court held in Sandusky

County in 1828 at

Lower Sandusky, as is learned from a

statement related

Seneca John, Indian Chief 137

by Judge David Higgins in Knapp's

History of the

Maumee Valley. He was Judge of the

Common Pleas

Court from 1831 to 1837 and familiar

with the facts

related. He says he was informed that

Seneca John

was tried by a council of head men, and

that upon full

investigation was condemned to die, and

Coonstick was

required to execute his brother. During a session of

the Supreme Court (1828) someone in

Lower Sandusky

caused the arrest of Coonstick for

murder, on com-

plaints before a Justice of the Peace.

The facts in the

in the case being presented to the

Judges of Supreme

Court, they decided that the execution

of Seneca John

was an act completely within the

jurisdiction of the

Seneca Council; and that Coonstick was

justified in the

execution of a judicial sentence which

he was the

proper person to carry into effect.

The case was dismissed and Coonstick

discharged.

No record, however, of the case is

found, but there is

no doubt as to the fact stated. Thus, Seneca John,

though he was killed on a false charge

prompted by

jealousy, yet as the form of the law of

the tribe had been

followed in his trial and condemnation,

his execution

was not regarded as murder in the legal

sense. It was,

however, cold blooded murder

morally. Here as

formerly, in a bigoted portion of

so-called civilized

people, of our own country, cold

blooded murders were

committed in the name of punishment for

this so-called

crime of witchcraft.

THE RESERVATION

In 1817, by treaty the Indians ceded to

the United

States all their claim to lands in

Ohio, except cer-

tain reservations. Among these was that

known as the

138 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society

Publications

Seneca Reservation. This consisted as

finally concluded

of 40,000 acres on the east side of the

Sandusky

River in the counties of Sandusky and

Seneca. About

one-fourth of the area was in Sandusky

County. The

boundaries of the reservation may be

described as fol-

lows:

Commencing on the east bank of the

Sandusky

River in Ballville Township, Sandusky

County opposite

the mouth of Wolf Creek, running thence

east through

the north parts of sections 29, 28, 26,

and 25 in said

township, and section 30, 29, 28 and

into the northwest

quarter of section 27 in Green Creek

Township, thence

through the west parts of said section

27, and section

34 in Green Creek Township south to the

boundary lines

between Sandusky and Seneca Counties,

thence continu-

ing south centrally, through the

townships of Adams

and Scipio in Seneca County to a point

in the latter

township on the line between sections 9

and 10 from

which point a line running straight

west strikes a point

80 rods south of the south line of

section 8 in Clinton

Township on the east bank of the

Sandusky River, and

thence northerly along the meandering

of the river in

said counties of Seneca and Sandusky to

the place of

beginning.

Owing to the increasing white

settlements about the

reservation, with the consequent

encroachments of civili-

zation on the savage life of the

occupants and disap-

pearance of game, the reservation was

becoming unsuit-

able as an abode for them, and

accordingly they decided

to abandon it for a home in the West

beyond the then

pale of civilization, and under the

treaty of Washington

made on the 28th day of February, 1831,

they ceded the

Seneca John, Indian Chief 139

entire reservation to the United

States. The treaty

provided that the United States should

sell all the land,

deduct from the proceeds certain

expenses and $6,000.00

advanced to the tribe and to hold the

balance of the pur-

chase money until the same should be

demanded, by the

chiefs, and in the meantime pay them 5%

interest on

same. On the part of the Senecas the treaty was

signed by Coonstick, Hard Hickory, Good

Hunter, and

Small Cloud Spicer. In 1831 the tribe in a body, a

sorrowful procession it may well be

imagined, departed

from the land of their birth, their

beloved hunting

grounds, and the graves of their

kindred dead, for their

new home beyond the Mississippi. In

1832 by proclama-

tion of President Andrew Jackson, the

lands of the

reservation were surveyed and placed on

sale by the

United States Government.

NOTES

Judge David Higgins, to whom reference

is made

in the preceding article, gives a very

different story in

regard to the character, trial and

execution of Seneca

John. This is recorded in Knapp's History

of the Mau-

mee Valley, pages 282-283:

"During the session of the Supreme

Court at Fremont, in

the the year 1822, (I may be

mistaken in the year), some person

in Fremont (then Lower Sandusky)

instituted a complaint be-

fore a Justice of Peace against the head

chief of the Senecas for

murder, and he was arrested and brought before the

Justice, ac-

companied by a number of the principal

men of his tribe. The

incidents upon which this proceeding was

founded are very in-

teresting as illustrating the Indian

life and character. With this

head chief (who among the Americans

passed by the appelation

of Coonstick) I was somewhat acquainted.

He was a noble

speciman of a man, a fine form,

dignified in manner, and evincing

140

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

much good sense in conversation and

conduct. Some two years

before this time, in prospect of his

tribe removing to the west

of the Mississippi, Coonstick had

traveled to the West, and had

been absent a year and a half in making

his explorations. The

chief had a brother who was a very bad

Indian, and during the

absence of the chief, had made much

disturbance among the

tribe; and among other crimes, he was

charged with intriguing

with a medicine woman and inducing her

to administer drugs to

an Indian to whom he was inimical, which

caused his death.

When the chief returned home, he held a

council of his head

men, to try his bad brother; and, upon

full investigation, he was

condemned to be executed. The

performance of that sad act

devolved upon the head chief-and

Coonstick was required to

execute his brother. The time fixed for

the execution was the

next morning. Accordingly, on the next

morning, Coonstick,

accompanied by several of his head men,

went to the shanty

where the criminal lived. He was sitting

on a bench before his

shanty. The party hailed him, and he

approached them, and

wrapping his blanket over his head,

dropped on his knees before

the executing party. Immediately

Coonstick, raising his toma-

hawk, buried it in the brains of the

criminal, who instantly ex-

pired. These facts being presented to

the Supreme Court, they

decided that the execution of the

criminal was an act completely

within the jurisdiction of the chief,

and that Coonstick was

justified in the execution of a judicial

sentence, of which he was

the proper person to carry into effect.

The case was dismissed

and Coonstick discharged."

Sardis Birchard in his reminiscences

recorded in the

work above quoted bears favorable testimony

to the

character of Seneca John and states

that on the infor-

mation furnished by Hard Hickory and on

the approval

of Tall Chief, Steel and Coonstick were

arrested. At

the trial, however, Tall Chief contrary

to expectation

did everything in his power to defend

Steel and Coon-

stick.

The story as related by Mr. Meek is

based largely

upon the report of Henry C. Brish,

Indian sub-agent at

Upper Sandusky, and supported by the

reminiscences of

Sardis Birchard. In other words, the foregoing con-

|

Seneca John, Indian Chief 141 tribution is supported by the testimony of two men who personally knew Seneca John, while Judge Higgins does not seem to have known him but had met and was favor- ably impressed with the appearance of Chief Coonstick. The Judge might have felt also that it was his duty to defend the action of the Supreme Court in this case. Editor. |

|

|