Ohio History Journal

BEGINNINGS OF THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

IN OHIO

by WILBUR H. SIEBERT

Professor Emeritus of History, Ohio

State University

The presence of fugitive slaves in Ohio

was evidently one

of the reasons for the enactment of the

Black Laws by the Gen-

eral Assembly in January 1804. These

laws provided that any

one harboring or secreting such

"objectionable" intruders, or

obstructing their owners in retaking

them should be fined from

$1O to $50 for each offense. It was also

provided that the claim-

ant, on making satisfactory proof of

ownership of a slave before

a magistrate within Ohio, would be

entitled to a warrant direct-

ing the sheriff or constable to arrest

and deliver the runaway

to the claimant. Any person attempting

to kidnap or remove a

Negro from the State without proving

title to the property was

liable, on conviction, to a fine of

$1,000, one half for the State

and the other for the informer, the

kidnaper being liable also to a

damage suit by the party injured.

This act was followed by another in

January 1807, which

was reenacted and reprinted in 1811,

1816, 1824, and 1831, re-

quiring in addition that no Negro or

mulatto should be permitted

to migrate into and settle within Ohio

without giving, within

twenty days, a bond of $500, with two

competent sureties, to

guarantee his good behavior and to pay

for his support if unable

to support himself. Any person

employing, harboring, or con-

cealing a mulatto or Negro contrary to

the provisions of this act

should forfeit not more than $100, one

half for the informer and

the other for the use of the poor of the

township where he resided.

These laws were not repealed until

February 10, 1849.1

It seems that the first authenticated

capture and release of a

1 Ohio Laws, II, 63-66, reprinted in O. L., VIII, 489-492; Western Reserve His-

torical Society, Collections,

Publication No. 101 (Cleveland, 1920), 55-56.

70

BEGINNINGS OF UNDERGROUND RAILROAD IN

OHIO 71

fugitive slave in Ohio occurred in the

opening year of the War

of 1812. In that year Canada gained a

prominence that recom-

mended it to the slaves yearning for a

land of liberty. Many

of their young masters took part in

military campaigns extending

to the Great Lakes, which imparted some

geographical ideas to

the Negroes watching the departure of

the uniformed whites.

Doubtless some of those canny and

adventurous slaves trailed

behind along. northward lines of march,

easily eluding the atten-

tion of people deeply interested in

military matters.

However one such pilgrim was captured at

Delaware, Ohio,

in 1812. His hands were tied together

and a rope connected him

with his captor on horseback, behind

whom he walked or ran as

they moved south on the road to

Worthington. Some time before

the rider and his captive arrived in the

village, word was brought

of their approach, and Colonel James

Kilbourne, the founder

and justice of the peace of the village,

suggested that the fugitive

be released. Villagers gathered while

the Colonel halted the rider

and talked to him. Suddenly a man ran

from a neighboring

building with a butcher knife and cut

the captive's cords. The

justice gave the parties a hearing and

decided that the Negro was

free.

Worthington was then a supply depot for

United States

troops at Sandusky. From Worthington

government wagons were

frequently moving war materials

northward. The Negro was

placed in one of these wagons and sent

towards Lake Erie. The

claimant quickly mounted his horse and

galloped south to Frank-

linton for a warrant to recover the

freed Negro. Upon his return

the latter was brought from up the road,

another hearing was held,

the Negro was again released and bundled

into a government

wagon for the trip to Sandusky.2

The late Colonel James Kilbourne, of

Columbus, Ohio, grand-

son of the founder of Worthington, had

not heard of the above

incident. He stated, however, that his

grandfather was "active

in assisting fugitive slaves on their

way to Canada," and that

2 Letter

from Robert McCrory, Marysville, Ohio, September 30, 1898, telling

the story told him by Richard Dixon, a very early

settler.

72 OHIO

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

they were concealed at times in his

house in Worthington.3 This

village is about ten miles north of

Columbus, in approximately the

geographical center of the State.

Southern soldiers returning to Kentucky

and Virginia from

the War of 1812 carried back the news of

an alien land beyond

the Great Lakes. Many of the slaves were

eager but unpretend-

ing listeners to such talk and picked up

more information about

Canada as opportunity offered. They

learned to know the north

star as marking the cardinal direction

they should take in their

flight, making their plans accordingly.

As early as 1815 many

fugitives began to traverse the Western

Reserve to reach focal

points for crossing Lake Erie, being

directed and assisted by

antislavery friends.4

The next earliest Underground activities

in Ohio, revealed

by research and correspondence with

abolitionists and their kin-

dred, were those of Isaac Mullin and his

son, Job, a mile north

of Springboro, close to the north

boundary of Warren County.

Springboro was a Quaker neighborhood.

The Mullins settled

there in 1802, when there were only

three other families living

within ten miles of them. They raised

ten children, Job being

born in January 1806. By 1816 the

Mullins were aiding fugitive

slaves. Neighbors thus engaged then and

later were Jonah D.

Thomas, Samuel Potts, Jonathan Wright,

Jesse Wilson, Job Carr,

and Joseph Evans. In 1821, at the

age of fifteen years, Job

Mullin was sent at night on horseback

down to the village to

fetch a runaway slave. During the next

year Job learned to

weave and turned out homespun for most

of the family clothing

for several years. At one time in the

loft over his loom room six

fugitives were secreted for a

fortnight--a man, his wife, and

their children. Sometimes they were

noisy until Job silenced

them by pounding on the floor with a

cane when he saw someone

approaching. Isaac Mullin harbored other

fugitives at various

times, and so did Job and his wife in

their separate home from

1829 on.

3 Letter from Col. Kilbourne, Columbus, Ohio, August 22, 1898.

4 Henry Wilson, History of

the Rise and Fall of the Slave Power (3 vols.,

Boston, 1822-77), II, 63.

BEGINNINGS OF UNDERGROUND RAILROAD IN OHIO 73

The wayfarers were sent or brought to

the Springboro neigh-

borhood from Shaker Village, nine miles

directly south and five

miles west of Lebanon. Job also knew of

Waynesville, ten miles

east of Springboro, as an Underground

center. Achilles Pugh

was an operator there.5 Probably

it received its early passengers

also from Shaker Village. The crossing

of the Ohio River was

made thirty miles to the south, from

which the trail led up to the

west central part of Warren County.

R. G. Corwin, long a resident of

Lebanon, first aided run-

aways at his father's about 1829, but

was sure that the secret

work had been going on long before. He

said it had gradually

increased until 1840, continuing at a maximum

thereafter.6

By 1816 slaves were escaping across the

Ohio River near

North Bend, fourteen miles west of

Cincinnati. Their course of

travel followed streams northward where

practicable, across five

counties and northeast through Auglaize

County near the Shawnee

village where Wapakoneta now stands.

They continued on up to

Oque-no-sie's town on the Blanchard

River, in Putnam County,

where the village of Ottawa is, thence

somewhat east of north to

the grand rapids of the Maumee, where

that river could be forded

most of the year, and through the Ottawa

village of Chief Kin-

je-i-no, where the red men were friendly

to the fugitives.

Befriending these seekers of

freedom was practiced also

by the Howard family on the Maumee. They

had anchored their

schooner near the picketed walls of old

Fort Meigs in the summer

of 1821 and remained there through the

winter a year and a half

later. They then removed to Grand

Rapids, where Edward How-

ard, the head of the family, built their

cabin on the south side

of the Maumee, opposite Kin-je-i-no's

village. There the How-

ards lived with their young son, D. W.

H. His only playmates

were the Indian children, and from his

sixth to his tenth year

he attended the Indian Mission School,

eight miles below his

home.

Edward Howard hid fugitive slaves in the

dense, swampy

5 Letter from W. H. Newport, Springboro,

Ohio, September 16, 1895, for his

father-in-law, Job Mullin.

6 Letter from R. G. Corwin,

Lebanon, Ohio, September 11, 1895.

74

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

forest near his cabin. When they were in

camp or were ready

to move towards Canada, Mrs. Howard

supplied them generously

with corn bread, boiled venison, and

pork. They were guided

along the course of the Maumee by Howard

and his son.

An Indian friend divulged to the Howards

that a party of

their runaways in the woods was being

watched by spies for the

slave hunter Richardson, a Kentuckian,

who lived at Roche De

Boeuf (Standing Rock) ten miles below

the rapids. The usual

trail for such travelers passed three

miles west of Richardson's.

Hoping to elude pursuit Howard and his

boy led their party

three miles east of the Kentuckian's

lair, then back into the trail,

leaving an armed guard in ambush to

shoot a horse of the pur-

suers, if necessary, and bring up the

rear. After the Howards

and their party had advanced several

miles, they heard the beat

of horses' hoofs behind them. Then the

sharp crack of a rifle

echoed through the dark forest, and a

wounded animal pitched

to the ground. That shot had the double

effect of causing the

immediate retreat of the pursuers and

hastening forward the

fugitives and their conductors.7

In 1815 Benjamin Lundy organized the first

antislavery

society at St. Clairsville, Belmont

County, about sixteen miles

southwest of Mt. Pleasant, Jefferson

County, where, in 1821, he

established the first abolition paper

ever published in the United

States. Those agencies spread their

leaven in that region. 'Both

Mt. Pleasant and its northern neighbor,

Smithfield, were Quaker

settlements where fugitive slaves were

welcomed, harbored, and

moved on towards the King's Dominion as

early as 1816 and

1817.

The indications are that Benjamin H.

Ladd was a pioneer

befriender of fleeing slaves at

Smithfield, where he had settled

in 1814, and that the Quaker merchant,

Finley B. McGrew, played

a similar role at Mt. Pleasant, the

large, dark cellar of his store

providing temporary lodgings for a

succession of many runaways.

The towns named are only six or seven

miles west of the Vir-

ginia panhandle and about ten miles

northwest of Wheeling, from

7 Letter from Hon. D. W. H. Howard, Wauseon, Ohio, August

22, 1894;

Toledo Bee, August 18, 1894.

BEGINNINGS OF UNDERGROUND RAILROAD IN

OHIO 75

which slaves at first occasionally took

refuge with Jefferson

County friends. As the number of

fugitives increased year by

year, series of

"liberty-lovers," living at distances of from five

to twenty-five miles apart, united to

secrete and care for the

homeless Negroes and forward them to the

next station.8

By 1817 Kentucky masters were protesting

over the escape of

their slaves into Ohio and neighboring

free states, bewailing the

fact that they could recover but

few. These complaints were

embodied in resolutions of their

legislature, transmitted that year

by their governor, charging the free

states with failing to enact

and enforce laws for the more effectual

reclamation of fugitive

slaves. In October 1817 Governor Thomas

Worthington of Ohio

defended conditions under his

jurisdiction by replying that the

fugitive act was fully executed, that

the writ of habeas corpus

often protected alleged runaways, and

that proofs frequently were

found to be defective.9

Nevertheless Ohio was infested with

slave hunters who were

so unprincipled that they kidnaped free

persons of color and sold

them into slavery. Wherever possible

these manstealers avoided

appearing before a magistrate to prove

property and got away

with their victims. This was already

easier in general than to

recover hidden passengers of the

Underground Railroad, or to

take them by violence from their

defenders. Furthermore sales

of kidnaped Negroes were far more

remunerative than rewards

for reclaimed fugitives.

The Ohio legislature would not tolerate

kidnaping and passed

an act on January 25, 1819, requiring

that the culprit be taken

before a judge of the circuit or

district court, or a justice of

the peace, in the county where he had

been seized. On conviction

the kidnaper was to be confined in the

state penitentiary at hard

labor for from one to ten years at the

court's discretion. This

law was re-enacted and reprinted in 1824

and 1831.10

8 Ohio State Archaeological and

Historical Quarterly, VI (1898), 274-275, 293;

conversation with J. C. McGrew, Columbus, Ohio, August, 1895;

J. A. Caldwell,

History of Belmont and Jefferson

Counties, Ohio (Wheeling, 1880), 534-535.

9 Western Reserve Historical Society, Collections, Publication

No. 101 (Cleve-

land, 1920), 73, 74.

10 Ibid.

76

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

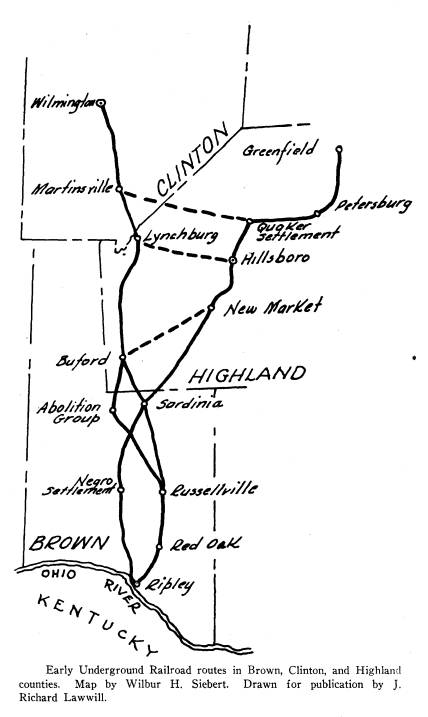

Brown County is the third county facing

the Ohio River

from the western boundary of the State.

Villages of the county's

southern expanse soon became the seats

of Presbyterian congre-

gations and pastors, a considerable part

of whom had withdrawn

from the slave states out of disgust

with the "peculiar institution."

Ripley, on the river, was one of these.

It was a convenient place

to cross, having Negro as well as white

townsmen who would

help seekers after freedom.

This clandestine aid evidently began not

long after the close

of the War of 1812. Theodore

Collins informed the writer that

his family settled at Ripley in 1813 and

engaged in Underground

work from its beginning. They had to be

very sly to keep the

proslavery element from discovering how

they operated. Collins'

sons took his horses from the stable for

riding northwards with

the runaways.11

When the Rev. John Rankin assumed charge

of the Presby-

terian Church in Ripley, on January 2,

1822, the antislavery

movement in Ohio was near its birth and

the Underground road

of Brown County found a vigorous

promoter. In 1823 Rankin

erected a house on Front Street, where

he and his family lived

for several years. In 1824 he published

his "Letters on Slavery,"

advocating immediate abolition, in a

local newspaper, The Casti-

gator. They aroused the consciences of many persons through-

out the countryside to the point that

they began secreting fugitives

temporarily and supplying their needs

until they could be safely

conveyed or directed to the next

station.12

Meanwhile, in 1820, two settlements of

freed slaves were

established in Brown County, one three

miles from Georgetown

and nine miles north of the Ohio River,

and the other three miles

east of where Sardinia was laid out. The

one nearer the river

quickly began to attract runaways from

the other side to the

obscurity of its numerous hiding places.

However the freedmen

were timid about harboring such guests

and were glad to run them

11 Conversation with Mr. Collins,

Ripley, Ohio, April 12, 1892.

12 Letter from Dr. Isaac M. Beck, Sardinia, Ohio, December 14, 1892.

78

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

ten miles northeast to secure the better

protection afforded by the

white abolitionists of Sardinia.13

In 1826 and 1828 Rankin's Letters were

issued in book form

and circulated widely. They spread the

talk about the antislavery

men at Ripley and vicinity until slaves

in actual or contemplated

flight knew they had good friends across

the river. Both Rankin

and Dr. Alexander Campbell, living in

the heart of the village,

certainly aided such slaves as came to

them, but the former un-

consciously expanded his services to the

northbound travelers to

wholesale proportions, in 1828, by

removing with his family into

the new brick house on the crest of the

hill overlooking the town.

Their habitation now stood in plain view

of observers on the

Kentucky shore who had humane reasons

for locating the place.

Candle lights at the gable windows were

pointed out at night to

eager slaves during thirty-five years to

direct them to a safe

haven. Rankin's frequent absence

establishing new churches or

lecturing against slavery did not

interrupt their reception. They

were welcomed and fed by Mrs. Rankin,

whose six sons knew

good places, both indoors and out, to

hide them, and when and

how to take them to the next station.

Their first trips were made

to Sardinia, a distance of twenty-one

miles, where they probably

delivered their charges to one of the

Pettijohn brothers, who lived

near the village. They soon shortened their

journey up the road

to six miles, that is, to the village of

Red Oak.14

When Ripley College was founded by

citizens of the town

about 1830, Rankin became its president

and students were at-

tracted from far and near. Among the

subjects they were taught

was the doctrine of human liberty which

not a few of them put

into practice by "carrying the war

into Africa." The students

found frequent nocturnal opportunities

to cross the river in

skiffs from Ripley and bring back

refugees from the opposite

bank.15

Red Oak village was founded by a band of

antislavery Pres-

13 Ibid.

14 Pamphlet: Ceremonies Attendant

upon the Unveiling of a Bronze Bust and

Granite Monument of Rev. John Rankin . .

. (n.p., May 1892).

15 Ibid.

BEGINNINGS OF UNDERGROUND RAILROAD IN

OHIO 79

byterians who had immigrated from North

Carolina in the early

years of the 1800's, their leader being

the Rev. James Gilliland.

Among them were Robert and William

Huggins, brothers, who

opened their doors for runaways brought

from Ripley after dark.

Neighbors shared in this illegal

hospitality. Somewhat later the

Huggins brothers removed to the North

Fork of Whiterock

Creek, five miles west of Sardinia.

There they still operated

stations, their sons, especially

Robert's five, running Underground

"trains" on a night schedule

twenty miles up to Martinsville, via

Buford and Lynchburg. At Martinsville

Aaron Betts and his

family were zealous workers both in

harboring passengers and

passing them on nine miles to

Wilmington.16

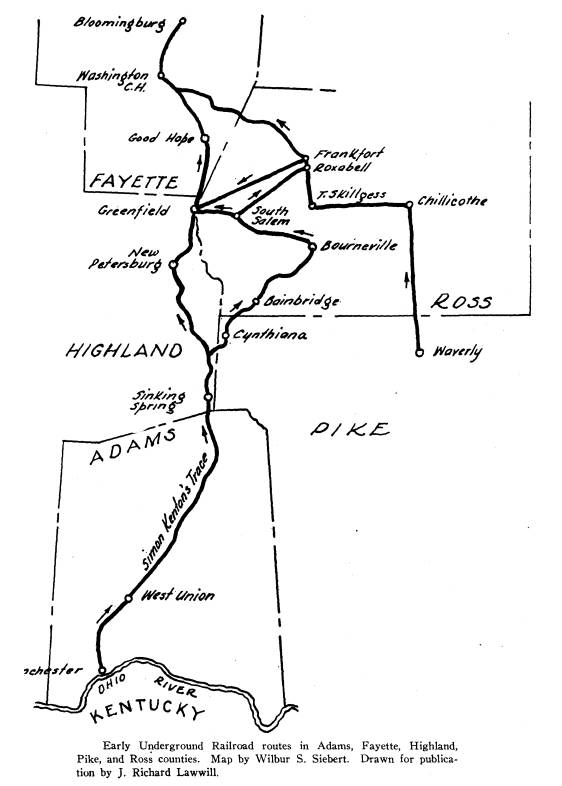

The route running northwestward from

Sardinia via Buford

and Lynchburg to Martinsville and

Wilmington was the western

branch from Sardinia. There was also an

eastern branch, run-

ning northeastward about eleven miles to

New Market, five

miles more to Hillsboro, and six miles

to a Quaker settlement,

Samantha. There it turned sharply east

eight miles to stations

at New Petersburg and three miles on to

Paint Creek, up which

it followed four or five miles to the

abolitionists of the Greenfield

neighborhood. The two branches were

distinct, but several cross-

country switches connected them so that

in time of pursuit pas-

sengers could be readily transferred

from one line to the other.

The broken lines on the map indicate the

normal locations of the

switches.17

As early as 1820 traffic on

the Underground Railroad had

begun in and near Pickrelltown, in

southeastern Logan County,

three tiers of counties from the State's

west boundary and a little

north of its center. Mahlon Pickrell, a

pioneer stationkeeper of

Pickrelltown, fixed the year and told of

his associate, Mahlon

Stanton, son of Benjamin Stanton, as a

principal conductor of the

runaways eastward to the Alum Creek

Friends' settlement in

Morrow County. Young Stanton hauled his

Negro passengers

at night by team and wagon over a

corduroy road through "the

black swamp," sometimes halting on

stormy nights in that dismal

16 Letter from Henry M. Huggins,

Hillsboro, Ohio, September 20, 1895.

17 Ibid.

80

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

place to feed his jaded horses with

oats. At first his trip was

thirty-five miles across Union County

and northeast about seven

miles beyond the town of Delaware to the

settlement. Both the

beginning and end of this journey were

Quaker villages. Later

the trip was shortened a dozen miles by

the appearance of several

new stations on the west side of the

Scioto River, six miles west

of Delaware.

Besides the Stantons and Mahlon

Pickrell, other friends of

the slave at Pickrelltown were Asa and

Silas Williams, Levi

Townsend, and some who were less active.

Pickrell was often

summoned in the night to admit fugitives

and their guides to his

large and commodious house, which became

alive with the sub-

dued stir of feeding and lodging the

Negroes and affording rest

and refreshment to their conductors.

Outside the horses were

well attended to. Mahlon Pickrell's

neighbors credited him with

sheltering and feeding more runaways

than anybody else of the

vicinity.18

Spring Hill farm, a mile and a half

north of Massillon,

Stark County, early became the property

and the home of the

noted Quaker preacher, Thomas Rotch, and

his wife, Charity,

immigrants from Massachusetts in 1812.

Their farm was fifty

miles south of Cleveland and an equal

distance northwest of the

upper Ohio. It was a favorable location

for a couple that ex-

tended hospitality to escaping slaves

and speeded them to their

port of departure. Their services were

much in demand, although

the husband's work was cut short by his

death in September 1823.

An interesting illustration is preserved

to us of the dignified

and impressive way in which Thomas Rotch

treated slave hunt-

ers at Spring Hill farm in April 1820. A

slave woman and her

two children had arrived and been

secreted in the loft of the

springhouse almost adjacent to the

residence. Next morning two

strangers rode up to the door and began

to explain their mission

and to show their search warrant. One of

them was the notorious

De Camp, whose villainous practice was

to plan the escape of

slaves so as to seize them more easily

for the rewards offered

by their masters.

18 Letter from Mahlon Pickrell,

Pickrelltown, Ohio, September 1894.

BEGINNINGS OF UNDERGROUND RAILROAD IN

OHIO 81

The hunters were invited into the house

and were quietly

encircled by the family and several farm

hands. Friend Rotch,

a man of fine appearance and native

shrewdness, let them talk

while he kept silent about the slaves.

At length he broke in to

ask if one of the pair was De Camp. When

one of them admitted

that he was De Camp, Rotch stated that

he expected to have

some very important business with him,

and it would be well for

him to be prepared for it. The strangers

glanced about uneasily,

feeling uncomfortable within the circle,

and suddenly broke for

outdoors. Leaping on their horses, they

galloped through the

gateway never to return. The fugitives

were soon sent safely

northwards.19

Thomas and Charity Rotch had a group of

fellow-workers

in their community, including the

Quakers. Robert H. Folger,

of Massillon, was one of these. He

reported that the first fugi-

tive slave he had any knowledge of was

sent to Thomas Rotch

in 1820.20 Irvine Williams, who had come to Massillon with

Friend Rotch, was another worker in the

Underground. Late

in November 1827 the highly intelligent

mulatto, James Bayliss,

settled in the town and learned at once

of fugitives passing

through. He did not then meet them

because at that time they

were looked after chiefly by local

Quakers, including James Austin

and Richard Williams. Non-Quakers taking

part in the work were

Matthew and Samuel Macy and several

Negroes. Charles Grant,

a Negro conductor, often borrowed a

horse and wagon from

Bayliss to carry fugitives to the house

of a Negro farmer, Gaskin

by name, four miles north and a little

east of Massillon. He

delivered them also to a Negro named

Tripp three or four miles

farther on, or to Tripp's neighbor,

Isaac Robinson, who was half

Negro and half Indian. Conductor Grant

also landed passengers

at the homes of Quakers up the line.

Sometimes Bayliss and

his associates forwarded travelers at

night twenty miles northeast

to Reuben Irwin, the Quaker preacher at

Marlborough, or to his

parishoner, Samuel Rockhill, or to the

Quaker, Barclay Gilbert.

living on a farm a few miles forther

north. Close to Limaville,

19 William

Henry Perrin, History of Stark County, Ohio (Chicago, 1881).

373-374.

20 Conversation with Mr. Folger,

Massillon, Ohio, August 15, 1895.

82

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

which lies several miles northeast of

Marlborough, Isaac Choates,

a member of the Friends' Society,

received fugitives from Mas-

sillon and its outlying stations.

Occasionally runaways reached

town by following the towpath of the

canal, thus avoiding the

public roads.21

The first escaped slave known to have

arrived at Sandusky,

on the shore of Lake Erie, reached there

in the fall of 1820. He

had traveled on foot through the

sparsely settled country, aided

by settlers here and there, until he was

welcomed at Abner

Strong's place, on Strong's Ridge, at

Lyme, in Erie County,

twelve miles from the port of Sandusky.

Strong kept an Under-

ground station, with passenger service

evidently to Marsh's tavern

in Sandusky. John Dunker, the Negro

hostler of that tavern, and

a Mr. Shepard, captain of a sailing

vessel, one of its regular

boarders, secreted this runaway.

The slave's master arrived in town soon

after, put up at the

tavern, and offered Captain Shepard $300

to find his "chattel."

For three days they hunted together in

vain. The master even

made the round trip to Detroit on the

steamboat Walk-in-the-

Water to search that boat. As soon as the boat had

disappeared

on her outward course, Captain Shepard

sailed away with the slave

to land him at Fort Maiden, Canada.

Discouraged by his failure,

the Kentucky master paid his personal

and livery bills at the

tavern and turned his horse's head

southward.

According to the Hon. Rush R. Sloane,

long a resident of

Sandusky and a careful investigator of

the Underground Railroad

in the Firelands, the pioneer helpers of

fleeing slaves at San-

dusky were almost without exception

Negro citizens. He names

twenty-one as the most prominent. Among

them was Grant

Ritchie who opened the first barber shop

in Sandusky. After

assisting several fugitives to sail for

Canada, Ritchie was arrested

and prosecuted for assaulting the

claimant of a slave. A justice

of the peace bound him over to the Huron

County court of com-

mon pleas. At the next term in Norwalk

the defendant pleaded

not guilty, the prosecution was not

ready, and the barber was

21 Conversation with James Bayliss,

Massillon, Ohio, August 15, 1895.

BEGINNINGS OF UNDERGROUND RAILROAD IN

OHIO 83

sent back to Sandusky. Later the case

was dropped and Ritchie

removed to Canada for a period of years.22

From about 1820, if not earlier, Jabez

Wright, an associate

judge of Huron County which adjoins Erie

on the south, har-

bored, fed, clothed, and employed

runaways on his lands in Huron

Township. Early in 1824 the young woman

teacher of the judge's

children, living in his family, noticed

a fugitive about his grounds

and learned that he had been employed

there for several years.

In 1825 this slave was reclaimed by his

master, but escaped back

to Judge Wright and stayed with him for

some time.23

Fugitives were aided early in the town

of Coshocton, despite

its Democratic politics. The runaways

crossed the Ohio River

at and near Wheeling, West Virginia,

were hurried ten miles

west to St. Clairsville, then

thirty-seven miles farther to Cam-

bridge, and from there twenty-three

miles northwest to Coshocton.

This route was in operation as early as

1820. At Coshocton the

acknowledged host was a large,

intelligent, and respected Negro

named Prior Foster. He lodged the

fugitives in his double shanty,

standing on what was later known as the

Harbaugh Corner, and

accompanied them on the ferry boat

across the Muskingum River

to Hanging Rock. There they remained

hidden until they could

be forwarded at night to New Castle, in

the northwest corner of

Coshocton County. In an emergency they

could be sent over a

north branch from Hanging Rock.

Foster cared for one party numbering

twelve or fifteen and

took them to the ferry past the home of

William A. Johnston.

The latter's mother was on the watch for

them with a generous

basket of provisions. They received it

with joy and gave her

three lusty cheers.24

Two loud-spoken slave hunters from

Virginia posted hand-

bills in Coshocton, offering large

rewards for the capture of the

dozen or more fugitives who had lately

passed through the town.

A high-tempered citizen who heard one of

the Virginians talking

loudly about their "d--d

niggers" knocked him sprawling in the

22 Firelands Pioneer, n.s., V (July 1888),

28-29, 34.

23 Ibid., 34.

24 Letter from William A. Johnston, Coshocton, Ohio, August 23, 1894.

84

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

mud. The strangers took no further risks

but rode away in a

hurry.25

Doubtless the Ohio counties fronting on

slave territory were

entered by fugitives from the time the

Black Laws were first

enacted. This is indicated by the laws

themselves, but the testi-

mony of inhabitants does not go back

that far. In the case of

Adams, an Ohio River county a little

west of the midpoint of the

State's southern boundary, our

information carries back only to

1822. In the summer of that year the slave, Joseph Logan,

made

his way up from North Carolina, swam

across the Ohio near

Ashland, Kentucky, tramped northwest to

Portsmouth, and.west

to "the Beeches," near

Bentonville, in southwest Adams County.

Joseph's wife, Jemima, and child were

servants there to the Rev.

Thomas Smith Williamson. Joseph had been

there the year be-

fore with his master, and had returned

to his little family. They

probably lived with him now in his

cabin, from which he helped

Kentucky slaves northward. He carried a

club to ward off men

and dogs, and in tight places could rely

on Negro friends. Once,

when a dozen slave hunters surrounded

his cabin, he and his

fellows tricked them and got away.26

Advertisements of runaways in the early

newspapers of

Adams County, describing the chattels

and offering definite re-

wards, encouraged pursuit and recapture.

A Virginian named

Fountain Pemberton who lived less than a

mile north of Locust

Grove, in northeast Adams County, having

located there in 1808,

shared in such lucrative adventure. His farm

and habitation

were on the Maysville and Zanesville

road.27

Slaves from a portion of western

Kentucky early began to

enter Adams County, especially by way of

Manchester in the

southeastern corner. Simon Kenton's

trace led them thirty-one

miles northeast through hilly country to

Sinking Spring, just

inside of Highland County. Pioneer

station-keepers there were

Nathaniel Williams and Thomas Wilson. By

a trip of eleven

miles slightly eastward the travelers

arrived in Paint Creek Val-

25 Ibid.

26 Nelson W. Evans and Emmons B. Stivers, History of

Adams County, Ohio

(West Union, 1900), 583-586.

27 Letter from H. C. Pemberton, Cleveland, Ohio, ca. 1895.

86

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

ley below Bainbridge, Ross County. An

equal distance up that

valley took them to the mouth of the

Buckskin and the Green-

field neighborhood. There Adam H. Wilson

and William Doug-

lass were early operators. At Rocky

Spring, five miles south, the

shippers of "freight" were

Col. Thomas Rodgers, John Rippey

Strain, and Squire William Wilson. A few

miles in the opposite

direction the agents were Ebenezer

McElroy, Robert Templeton,

Henry Doster, Alexander Beatty, and

David Thormley.28

This section of the road was part of the

west branch that

connected southward with New Petersburg

and down to Sinking

Spring. The Miller family, relatives of

the Stewart clan, kept

the station at New Petersburg. North of

Greenfield the road ran

through Good Hope and on up to

Washington C. H. and Bloom-

ingburg. This whole length totaled some

forty miles and, being

most direct, was preferred when it was

open.29

There was another main route, an east

branch from Sinking

Spring by way of Cynthiana, in the

northwest corner of Pike

County, and northeast through Bainbridge

to Bourneville, on the

lower reach of Paint Creek. At

Bourneville the trail turned

sharply northwest to South Salem, which

was a junction that had

a shortline connection from Greenfield

and an outbound track

northeast to Roxabell and Frankfort.

From Frankfort the route

ran northwest to Washington C. H. and

Bloomingburg. The

operators at South Salem were

Satterfield Scott and John Sample.

Opposite to Frankfort, on the west bank

of the North Fork of

Paint Creek, stood the mansion house

that was old Hugh Stewart's

station. His son, Robert Stewart, kept a

neighboring station and

often made a cross-country run eleven

miles westward to Green-

field with fugitives. Fellow operators

of his were Robert Gal-

braith and James Anderson.

Runaways were harbored in the Negro

settlement of Rox.

abell, a mile south of Frankfort, and

hauled from there to Wash-

ington C. H., where they were received

by Jerry Hopkins, Jacob

Puggsley, and others. In 1825 the small

group of operators at the

28 Conversation of Hugh S. Fullerton

with Stanley W. McClure, May 3, 1892;

letter from Rev. John W. McElroy, Ottumwa,

Iowa, September 17, 1896.

29 Conversation of Hugh S. Fullerton,

cited above.

BEGINNINGS OF UNDERGROUND RAILROAD IN

OHIO 87

county seat was strengthened by the

addition of the brothers, John

and Samuel Craig. The former had a

dry-goods store in the

town and lived there until his death in

1853. The latter removed

to Cambridge, Guernsey County, in 1840.

When there were spies

or pursuers in Washington, the wayfarers

were hurried to emer-

gency stations out in the country. One

of these was three-fourths

of a mile north of town, its keeper

being Edward Hall, a farmer

from Maryland, and the other was a

little more than a mile farther

on, where Thomas Brown operated.

Several miles east of town William

Edward's "depot" pointed

significantly towards Circleville. Six

miles north of Washington

C. H. was Bloomingburg, whose most

active host to travel-worn

Negroes was the Rev. William Dickey, its

Presbyterian minister

from about 1815 to his death, December

6, 1857. His fellow-

workers were George Fullerton, the

brothers George and Hugh

Stewart, old Adam Steele, Wilson

Elliott, William Pickering,

Dr. Gillespie and his nephew, George,

and James McNamara.

A mile and a half southeast of town

William A. Eustick and

his son, Robert, cared for fugitives.30

The east branch, from Sinking Spring to

Bloomingburg by

way of Cynthiana, Bourneville, South

Salem, Frankfort, and

Washington C. H., totaled sixty-five

miles and was largely a

family and Presbyterian enterprise from

its start. Most of the

families that were concerned in the work

were related to the

Stewart clan by blood or marriage.31

Bloomingburg also received fugitive

slaves from Chillicothe

and the Scioto Valley to its south by

the mid-1820's. The early

managers at Chillicothe were a few

Negroes, including Charles

H. Langstren, who sent or conducted part

of the passengers ten

miles west to Joseph Skillgess, at Dry

Run Church, on foot or

horseback or by wagon in the night. Mr.

Skillgess forwarded his

wayfarers five miles north, by way of

Roxabell and Frankfort, to

30 Conversation

of Hugh S. Fullerton, cited above; "Rev. William Dickey," in

Presbyterian Historical Almanac and Annual Remembrancer

for 1864 (Philadelphia,

1864); letter from Rev. John W.

McElroy, cited above; conversation with Col. Thos.

L. Rankin, Chillicothe, Ohio, June 10, 1892; conversation with Rev.

R. C. Galbraith,

Chillicothe, Ohio, June 10, 1892; letter from V. D.

Craig, son of John Craig; letter

from R. S. Frame, Washington C. H., Ohio, July

13, 1892.

31 Conversation of Hugh S. Fullerton, cited above.

88

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Bloomingburg, directing them to William

H. Eustick, a little

southeast of town, or to the Rev.

William Dickey or other promi-

nent "railroaders" in

Bloomingburg. These in turn usually moved

them twelve miles farther north to

Mahlon Pickrell's place, in the

southern part of Madison County.32

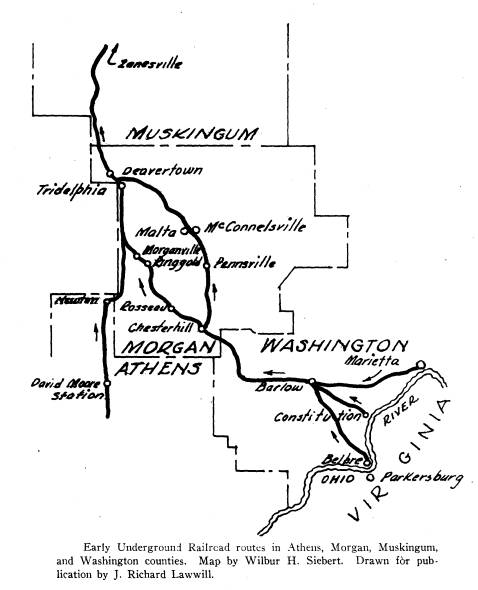

Morgan County adjoins the north side of

the west half of

Washington County. The latter's frontage on the Ohio River

afforded slaves handy crossings from western Virginia at Ma-

rietta, at Belpre, a dozen miles below,

and at other points. Near

the steamboat landing at Parkersburg,

just opposite Belpre, lived

"old Aunt Jinney," a slave who

blew the horn for the boats. She

was in the confidence of fugitives and

passed the word to Jona-

than Stone, T. B. Hibbard, or other

early emancipators across

the river as to where and when to meet

groups of runaways.33

James Lawton, of Marietta, was one of

these emancipators.

In 1818 he published a poem deploring

slavery and praising the

town of his choice for its freedom. We

quote but three lines:

No mourning slave the passing stranger

meets,

Blessed be thy name while fair Ohio's

waves

Shall part thy borders from the land of

slaves.

Mr. Lawton and others along the river

bank opened lines of

escape for the Negroes. In front of

Marietta and the village of

Harmar, to the westward, Vienna Island

served as a stepping

stone for fugitives coming at night in

skiffs and flatboats.34

At the river hamlet of Constitution,

eight miles below Ma-

rietta, lived Judge Ephraim Cutler, the

grandfather of Rufus R.

Dawes, known to his fellow-townsmen

after the Civil War as

General Dawes. At the age of eight years

Rufus and his mother

visited the grandfather, and one night

were awakened from sleep

by a team and wagon coining over the

hill down to the river.

The driver uttered a shrill hoot-owl

tremulo, which was at once

answered in like manner from the other

side, and a boatload of

fugitive slaves was rowed across. The

method was already work-

32 Conversation with Joseph Skillgess,

Urbana, Ohio, August 14, 1894.

33 Conversation with Miss Martha Putnam,

Marietta, Ohio, August 22, 1892.

34 Charles

Robertson, History of Morgan County, Ohio (Chicago, 1886), 429;

conversation with Miss Martha Putnam,

August 22, 1892.

|

89 |

90

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

ing smoothly, but there was a long and

perilous journey ahead

for the company just landed. Mrs. Dawes

got out of bed, called

her boy, and both knelt down while she

asked divine blessing and

guidance for the Negro people piling

into the wagon.35

The new routes originating at Marietta,

Constitution, and

Belpre converged at Barlow, eleven miles

west of the first named

town, and eight miles farther on turned

north and then west about

seven miles to Chesterhill, in south

central Morgan County. Ac-

cording to Robertson's History of

Morgan County, runaways were

being spirited through that district by

1820, the state road from

its river terminus at Marietta west for

a score of miles serving

as the main trunk for the secret

traffic. However the county

history does not explain that there were

two separate branches

of the Underground extending northward

from the Quaker set-

tlement of Chesterhill and joining at

Tridelphia and Deavertown,

in the northwest ell of the county. Of

these the east branch

passed through Pennsville, another

Quaker community, Malta,

McConnelsville on occasion, and advanced

twelve miles north-

westward up Wolf Creek to the junction

villages. The west

branch, by a shallow curve on that side,

ran through Rosseau,

Ringgold, Morganville, and proslavery

Portersville, through which

the conductors slipped with extreme

caution, and thus arrived at

the county terminals.

The first known mishap on the

Underground Railroad in

Morgan County occurred in the year 1820.

Already William

C-------- had a station on Wolf Creek, northeast of Chesterhill.

A slave who had fled from a Mr.

Anderson, of western Virginia,

sought protection there and was passed

on to William V--------

Traveling north, he lost the track and

stopped for information at

a tavern a little east of the later site

of Morganville. Unfortu-

nately his master had spent the previous

night there and offered

a reward of $25 for his apprehension.

The slave was therefore

held until his master came and paid the

reward and took him

away.36

The united-branches issuing from

Deavertown crossed the

35 Conversation with Gen. R. R. Dawes, Marietta, Ohio, August 22, 1892.

36 Robertson, Morgan County, Ohio,

150, 151.

BEGINNINGS OF UNDERGROUND RAILROAD IN

OHIO 91

sought protection there and was passed

on to William V-------

and by a curving but irregular course of

some nineteen miles

reached Putnam (now South Zanesville)

and, just across the

Muskingum River, Zanesville.

Fugitives not only arrived at Deavertown

and Zanesville

from the river towns of the lower half

of Washington County,

but by 1823 and 1824 they were being

brought there from the

upper northeast corner of Athens County,

the trip being thirteen

miles north from Newton. The Hon.

Eliakim H. Moore, a promi-

nent citizen of Athens, so informed the

writer in March 1892.

Most of the passengers were forwarded

northward from station

to station through Gallia and Meigs

counties into Athens. In 1817

David Moore, a migrant from

Massachusetts, father of Eliakim

and grandfather of David H Moore, later

a bishop of the Metho-

dist Episcopal Church, had settled on a

farm six miles north of the

town of Athens. During the decade he

spent there he engaged in

harboring runaways. He continued to do

so during the rest of his

life after moving three miles south of

town. The man to whom he

delivered his fugitives was his

brother-in-law, Solomon Newton,

who lived in the village of Newton,

sixteen miles north of the

county seat. Newton drove the Negroes

eleven miles north to

the Deavertown neighborhood.

Other pioneer helpers and forwarders of

fugitives in Athens

County were Eben Foster, Joseph B.

Miles, Charles Shipman,

John Gilmore, and Jack Howlett. So also

were the brothers

Elisha, Elansome, and John M. Hebbard,

who lived a little north

of the town of Athens. A cave in the

rocks near John Mc-

Dougall's place, six miles north of the

town, was used for hiding

hunted slaves.37

Mahoning County is bounded on the east

by Pennsylvania

and separated from the upper elbow of

the Ohio River by a single

county to the south. From 1823 to 1837

Dr. Jared Potter Kirt-

land dwelt in Poland, a pretty village

in the east central part of

the county. He was an imposing man, a

noted physician and

botanist, and a brilliant talker. His

kindly nature could not deny

37

Conversation with Hon. Eliakim H. Moore, Athens, Ohio, March 1892.

92

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

a welcome to fleeing slaves, who were

admitted to his house for

protection, food, and rest. He

personally conducted them to

stations in Pennsylvania.38

Nephews visited "Uncle Potter"

early in August 1874, and

after breakfast one morning gathered in

his library to hear him

tell the thrilling story of his aid to

fugitives, including two women

who sat in the darkened parlor while Dr.

Kirtland diverted their

masters in the kitchen. After the

departure of the slaveowners

the runaways were driven to the house of

Edward or Eli Kid-

walader, Quakers living six miles

distant at Edenburg, Pennsyl-

vania, on the Mahoning River. Among

other incidents, the rela-

tion of which continued until noon,

"Uncle Potter" told of the

slave Kitty's escape from the sheriff

and his companion in Brooks

County, Virginia.

Brief notes of these matters were

recorded by Charles J.

Morse, one of the nephews, in his diary.

He also learned of the

route through Poland. Quakers of Salem,

in the northernmost

section of Columbiana County, conveyed

the fugitives ten miles

somewhat east of north to operators at

or near Canfield, in Ma-

honing County. From there they were

transported eight miles

directly east to Dr. Kirtland. In

Canfield Dr. Chauncey Fowler

stowed slaves in his basement and

supplied them generously with

food and clothing. Two miles east of the

village lived his close

friend, Jacob Barnes, another ardent

worker. Both Barnes and

Fowler carried their passengers either

to Dr. Kirtland or to

Deacon James Adair who lived a mile and

a half northeast of

Poland.

From these operators near the

border of Mahoning

County the Negroes could be quickly run

to the Kidwaladers in

the Mahoning River bottom, a few miles

below Lowellville. Be-

tween Poland and Edenburg an alternative

station was kept by

the Sharpless family. At Youngstown, a few miles north of

Poland, fugitives could be conveniently

delivered to Richard

Holland and John Van Fleet.39

The present writer did not begin to

collect information re-

38 Letter from Miss Mary L. Morse,

Poland, Ohio, August 11, 1892; letter from

Mrs. Emma Kirtland Hine, Poland, Ohio,

January 23, 1897; letter from Charles J.

Morse, Evanston, Illinois, October 15,

1898.

39 Letter from Charles J. Morse,

October 15, 1898.

BEGINNINGS OF UNDERGROUND RAILROAD IN

OHIO 93

specting the Underground Railroad from

its members and their

descendants and neighbors until

1892. Already most of its

founders in Ohio were dead. If he could

have started at least a

dozen years earlier it is probable that

the origins of the movement

would have been found to be considerably

earlier than appear in

the foregoing pages. Doubtless also the beginnings

would have

been closer together in point of time in

various counties, especially

in those fronting on the Ohio River. As

the work was clandes-

tine, contemporary records were almost

never kept. Personal

recollections have been the chief

sources of information.