Ohio History Journal

MONUMENTS TO HISTORICAL INDIAN CHIEFS.

BY EDWARD LIVINGSTON TAYLOR.

It will always seem strange that the

Indian tribes erected

no monuments of an enduring character to

mark the last resting

place of their dead; especially so, as

they had constantly before

them the example of the burial mounds of

the race that pre-

ceded them in the occupancy of the

country, as well as the later

example of the white race, whose custom

of marking the graves

of their dead was familiar to them. It

is doubtful if the graves

of even a score of their most noted

chiefs or warriors could

now be certainly determined. Even the

exact burial spot of

that great and wise Chief Crane (Tarhe),

who was long the grand

sachem of the Wyandot tribe, cannot now

be definitely fixed,

although his death occurred as late as

the year 1818, at Crane

Town, in Wyandot county, Ohio, and his

burial was witnessed

by many hundreds of Indians of many

tribes and by many white

men. The grave of Chief Leatherlips

would not now be known

had it not been marked by a white man

who witnessed his ex-

ecution and burial.

Many chiefs have obtained a permanent

place in the history

of the country and have thus enduring

monuments, but even

such noted chiefs as Pontiac, Tecumseh,

Crane, Logan, Solomon,

Black Hoof, Little Turtle, Blue Jacket

and many others, who

were conspicuously active in the early

settlement of Ohio, and

most of them buried in Ohio soil, are

all monumentless and their

burial places are now unknown.

At all periods of the history of the

contact, and too often

conflict, between the white and red

races since the landing of the

Pilgrims, there appeared great and

worthy red men, actuated

by high purposes, whose lives and

characters were illustrated

and made notable by magnanimous and

noble deeds. Instances

of this kind fill all our history, not

only as to chiefs and warriors,

but as to many of the Indian women. It

has long been the

pride of many Virginia families to boast

that the blood of Po-

Vol. IX-l.

2 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

cahontas coursed through their veins.

This is the most noted

instance of that kind, but many other

Indian women are known

to have performed equally noble and

worthy deeds as those

accredited to Pocahontas, which were

followed by great and

lasting results for the good of humanity

and civilization.

The great conspiracy of Pontiac in 1763,

which was no less

comprehensive in its scope than the

complete extermination of

the white settlers and the white race in

the entire northwest

territory, was defeated by an Indian

woman, who revealed the

secret plans of Pontiac to Major

Gladwyn, who was then in

command of the fort at what is now the

City of Detroit. Pontiac's

plan was to obtain entrance to the fort

for himself and a large

number of warriors with concealed

weapons under the pre-

tense of a friendly conference and then

massacre the officers

and soldiers of the garrison. This fort

was the key to the

situation, and had it fallen, as eight

of the twelve forts attacked

did fall, it is far more than probable

that the dreadful purposes

of Pontiac would have, at least in a

great measure, succeeded,

and would have worked great and

permanent changes in the

history of the settlement of all the

territory of the great north-

west. These are but single instances of

Indian heroineism,

which might be indefinitely extended;

but this is not our pur-

pose at present. Our present purpose is

simply to call attention

to the singular fact that the white race

has almost entirely failed

of effort to preserve or commemorate the

names or mark the rest-

ing places of even the most noted and

illustrious of the Indian

race; although as to many of them the

white man is under the

highest and most sacred obligations. We

have possessed ourselves

of the vast continent which they once

occupied and have practically

extinguished the race, and yet have made

comparatively no effort

to perpetuate their history, or place

monuments to the memory

of even their greatest chiefs. The names

of their warriors have

fallen into our history as necessary

part of the narrative, with

little or no purpose to perpetuate their

fame or celebrate their

virtues. We erect all kinds of monuments

to our real, and too

often our imaginary, heroes, but there

has been almost an entire

neglect and failure of intentional

purpose to recognize the worth

and character of the heroes of the red

race by our people. That

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their

Monuments. 3

such a man as Chief Crane (Tarhe) should

be without a suitable

monument seems almost incredible, in

view of his long honorable

and useful life and his many virtues,

and especially his great

services to both races for their good. I

have seen and talked

with several persons who knew Chief

Crane in his lifetime, and

all testify to his high and honorable

character, as well as to his

great common sense and goodness of

heart. General William

Henry Harrison, who had the widest and

most accurate acquaint-

ance with, and knowledge of, the Indians

of the northwest

territory of any man of his time, gives

his high endorsement

as to the honor and worth of this great

and good chief, with

whom he was intimately acquainted. In

his report made to the

Secretary of War, March 22, 1814, he says:

"The Wyandots of Sandusky have

adhered to us throughout

the war. Their chief, the Crane, is a

venerable, intelligent and

upright man."

At another time, while speaking highly

of several important

chiefs with whom he had been largely in

contact, he designated

Chief Crane as "the noblest of them

all."

Mr. Walker, a half-blood Wyandot and a

well educated and

intelligent man, who was born at Upper

Sandusky in 1801, and

who went with his tribe when they

removed to the territory of

Kansas, of which he became its first

territorial governor, has

left a sketch of Chief Crane, which was

published in the "Wyan-

dot Democrat" under the date of

August 13, 1866. In that

sketch he says:

"When in his prime he must have

been a lithe, wiry man,

capable of great endurance, as he

marched on foot at the head

of his warriors through the whole of

General Harrison's cam-

paign into Canada and was an active

participant in the Battle

of the Thames, although seventy-two

years of age. He steadily

and unflinchingly opposed Tecumseh's war

policy from 1808 up

to the breaking out of the War of 1812. He maintained

inviolate

the treaty of peace concluded with

General Wayne in 1795 (the

Treaty of Greenville). This brought him

into conflict with

the ambitious Shawnee (Tecumseh), the

latter having no re-

gard for the plighted faith of his

predecessors. But Tarhe de-

termined to maintain that of his and

remained true to the Amer-

4 Ohio Arch.

and His. Society Publications.

ican cause until the day of his death.

He was a man of mild

aspect, and gentle in his manners when

at repose, but when

acting publicly exhibited great energy,

and when addressing

his people there was always something

that to my youthful ear

sounded like stern command. He never

drank spirits; never

used tobacco in any form.

"His Indian name is supposed to

mean crane (the tall fowl);

but this is a mistake. Crane is merely a

sobriquet bestowed upon

him by the French, thus: 'Le chef Grue,'

or 'Monsieur Grue,'

the Chief Crane, of Mr. Crane. This

nickname was bestowed

upon him on account of his height and

slender form. He had

no English name, but the Americans took

up and adopted the

French nickname. Tarhe or Tarhee, when

critically analyzed

means, At him, the tree, or at the

tree the tree personified.

Thus you have in this one word a

preposition, a personal pro-

noun, a definite article and a noun. The

name of your populous

township should be Tarhe instead of

Crane. It is due to the

memory of that great and good man."

Chief Crane was born near Detroit in

1742. He belonged

to the Porcupine tribe of the Wyandots

and from the time that

he was old enough to be counted as a

warrior he participated in

all the battles of his tribe down to the

battle of "Fallen Timbers",

in 1794. He was with Cornstalk at the bloody battle of

Point

Pleasant, West Virginia, which took

place October 1O, 1774.

General Harrison, when a young officer

in the United States

army, was engaged in the battle of

"Fallen Timbers" under Gen-

eral Wayne, August, 1794, where the

Indians were disastrously

defeated. In an address delivered by him

before the Historical

Society of Cincinnati, 1839, in speaking

of the Indian tribes en-

gaged in that battle, he says of the

Wyandots:

"Their youths were taught to

consider anything that had

the appearance of the acknowledgment of

the superiority of an

enemy as disgraceful. In the battle of

the Miami Rapids (Fal-

len Timbers), of thirteen chiefs of that

tribe who were present,

only one survived and he was badly

wounded."

The wounded chief was undoubtedly Chief

Crane, who was

badly wounded in the arm at that battle,

but escaped with his

life.

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their

Monuments. 5

Jeremiah Armstrong, who lived in

Franklinton and Colum-

bus from its earliest settlement to 1859

and was well known

to all the older residents, has left an

interesting narrative of

his experience while a prisoner with the

Indians, during which

time he saw much of Chief Crane.

Armstrong was born in

Washington county, Maryland, March,

1785, but his parents

removed to Virginia, opposite the upper

end of Blennerhasset's

Island, prior to 1794. In April of that

year he and his older

brother and sister were captured and

carried into Ohio by the

Indians of the Wyandot tribe. His mother

and other members

of the family, except his father, were

murdered. In their re-

treat they passed the points of

Lancaster, Columbus, Upper

Sandusky and on to Lower Sandusky at the

mouth of the San-

dusky River and Lake Erie. In his

narrative he says:

"On arriving at Lower Sandusky,

before entering the town,

they halted and formed a procession for

Cox (a fellow prisoner),

my sister, my brother and myself to run

the gauntlet. They pointed

to the house of their chief, Old Crane,

about a hundred yards dis-

tant, signifying that we should run into

it. We did so, and were

received very kindly by the old chief;

he was a very mild man,

beloved by all."

In speaking of the battle of

"Fallen Timbers," he says:

"In the month of August, 1794, when

I had been a prisoner

about four months, General Wayne

conquered the Indians in

that decisive battle on the Maumee

(Fallen Timbers). Before

the battle, the squaws and children were

sent to Lower Sandusky.

Runners were sent from the scene of

action to inform us of their

defeat, and to order us to Sandusky Bay.

They supposed that

Wayne would come with his forces and

massacre the whole of

us. Great was the consternation and

confusion; and I (strange

infatuation), thinking their enemies

mine, ran and got into a

canoe, fearing they would go and leave

me at the mercy of the

palefaces. We all arrived safe at the

bay; and there the Indians

conveyed their wounded-Old Crane among

the number. He

was wounded in the arm; and my friend,

the one that saved my

life, was killed."

This would seem to definitely determine

that it was Chief

Crane to whom General Harrison referred

as the only chief of

6 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

the Wyandots who escaped death at that

battle, but "was badly

wounded." The full narrative of

Jeremiah Armstrong, written

by himself in 1858, appears in Martin's

History of Franklin

County. He always retained until his

death a great reverence

and affection for Chief Crane.

It may be safely said of Crane that he

was the most influ-

ential chief in bringing about the

celebrated Treaty of Greenville.

He had the discernment to see that the

battle of "Fallen Timbers"

had broken the military power of the

Indians of the northwest,

and that peace was the only safety for

his tribe and race; so

he made haste to have the principal

tribes with whom he had

influence make a preliminary agreement

of peace with General

Wayne, and thus suspend hostilities

until the general treaty could

be made, embracing all the tribes.

Accordingly on January 24,

1795, the principal chiefs of the

Chippewas, Ottawas, Sacs, Pot-

tawattomies, Miamis, Shawnees, Delawares

and Wyandots en-

tered into a preliminary agreement with

General Wayne at Green-

ville, Ohio, to suspend hostilities

"until articles for a permanent

peace shall be adjusted, agreed to and

signed." It was further

agreed that "the aforesaid sachems

and war chiefs for and on

behalf of their nations which they

represent, do agree to meet

the above named plenipotentiary of the

United States at Green-

ville on or about the 15th day of June,

next; with all the sachems

and war chiefs of their nations then and

there to consult and

conclude upon such terms of amity and

peace as shall be for the

interest and to the satisfaction of both

parties."

This led to the celebrated and most

important Treaty of

Greenville, concluded August 3, 1795, in

the bringing about

of which no chief or warrior was so

influential as Chief Crane.

There were many turbulent and vindictive

chiefs and warriors

of the various tribes who opposed the

treaty and desired to con-

tinue their wars and forays against the

white settlers, and it

was a delicate and difficult task to

overcome and satisfy their

objections; and this could probably not

have been accomplished,

except by the strong influence and

persuasive arguments of

Chief Crane. Other influential chiefs

and warriors joined with

him in his efforts, but he was the

central and controlling source

of influence and power. It is now a

matter of history that with

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their

Monuments. 7

the exception of the wars and

disturbances excited by the rest-

less and turbulent Tecumseh and his

associates, resulting in

what is called the War of 1812, the

Treaty of Greenville ended

the long and bloody strife between the

red and white race in

the northwest territory.

Most of the tribes who were parties to

that treaty remained

ever true to its conditions,

notwithstanding the baneful influ-

ence of Tecumseh and his brother, the

Prophet, and other turbu-

lent spirits, who were for years

industriously endeavoring to

create a hostile feeling among the

Indians, and did draw away

many of them to their great detriment

and injury. Chief Crane,

however, with many other important

chiefs, remained true to

their treaty obligations, and greatly

hindered and balked the

schemes of the restless and ambitious

Tecumseh.

On June 21, 1813, Crane, at the head of

about fifty chiefs

and warriors, met in conference with

General Harrison at the

town of Franklinton (now Columbus), when

he, as their only

spokesman, assured General Harrison that

they would remain

true to their treaty obligations, and if

necessary join with him

in the prosecution of the war against

Tecumseh and the English

under General Proctor. This assurance

was of the greatest

possible benefit and advantage to

General Harrison at that crit-

ical period of the war and enabled him

to use his forces with

greater effect.

Chief Crane died at the Indian village

of Crane Town,

near Upper Sandusky, in Wyandot county,

Ohio, in November,

1818, being at that time seventy-six

years of age.

Col. John Johnston, then United States

Indian Agent, was

present at the funeral ceremonials. In

his "Recollections" he

says:

"I was invited to attend a general

council of all the tribes

of Ohio, the Delawares of Indiana, and

the Senecas of New

York, at Upper Sandusky. I found on

arriving at that place

a very large attendance. Among the

chiefs was the noted

leader and orator Red Jacket, from

Buffalo. The first business

done was the speaker of the nation

delivering an oration on the

character of the deceased chief. Then

followed what might be

called a monody or ceremony of mourning

and lamentation. Thus

8 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

seats were arranged from end to end of

the large council house,

about six feet apart. The head men and

the aged took their

seats facing each other, stooping down

their heads almost touch-

ing. In this position they remained

several hours. Deep, heavy

and long continued groans were commenced

at one end of the

row of the mourners and were passed

around until all had re-

sponded and these repeated at intervals

of a few minutes. The

Indians were all washed and had no paint

or decorations of any

kind upon their person, their

countenance and general deport-

ment denoting the deepest mourning. I

had never witnessed

anything of the kind and was told this

ceremony was not per-

formed but upon the decease of some

great man."

Crane was the chief sachem of the

Wyandots, to which tribe

was intrusted the grand calumet which

bound the tribes north

of the Ohio in a confederation for

mutual benefit and protection.

He was therefore at the time of his

death and for many years

before, the leading and principal

representative of his race in

the northwest. Aside from his own tribe

his death was mourned

by the Shawnees, Delawares, Senecas,

Ottawas, Mohawks and

Miamis assembled for that purpose.

Perhaps no chief in the

history of the Indian race had more

numerous or more sincere

mourners at his grave, and yet, although

but little more than

eighty years have passed since his

death, his grave is not only

unmarked, but unknown.

It is not fitting or seemly that his

name should be allowed

to be forgotten and his memory perish.

He was a wise and good

man and an honorable chief, well known

to the early settlers in

central Ohio, many of whom were honored

by his friendship

and all benefited by his influence. From

the time of the Treaty

of Greenville in 1795 to the time of his

death in 1818, a period

of almost a quarter of a century, during

which time the early

settlements in central Ohio were made,

he was more than any

other chief of his time the rock of

security and safety of the

white settlers. He frequently visited

Franklinton and was the

friend of Lucas Sullivant and his

associates, who, in the last

years of the last century, founded what

is now the City of Co-

lumbus. He often maintained his camp for

considerable pe-

riods at the celebrated Wyandot Spring,

on the west bank of the

|

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their Monuments. 9

Scioto, eight miles north of Columbus, at what is now known as Wyandot Grove. In September, 1883, the late Abraham Sells, |

|

|

|

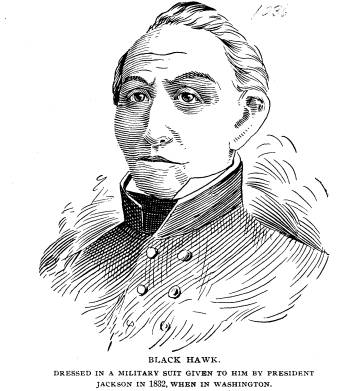

being one-half-blood French and his mother a full-blood Sac. |

10 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

He was not a chief by birth, but became

chief of his tribe by

reason of his own talents and efforts.

He was brave and skill-

ful in war and possessed of the gift of

oratory in an unusual

degree. He is said to have been vain and

mercenary, but he

had the high courage to withstand and in

a large measure

thwart the schemes and purposes of the

sullen and gloomy

Black Hawk, who was also a Sac chief of

great ability and

influence with both the Sac and the Fox

nations.

Chief Keokuk sustained almost precisely

the same rela-

tion to Black Hawk in 1832 that Crane

had sustained to Te-

cumseh twenty years before. Crane and

other well-disposed

chiefs restrained a large majority of

the Indians of the north-

west from engaging in the War of 1812;

and Keokuk did the

same in 1832 as to the Sac and Fox

nations, then living along

the Mississippi in Iowa and Illinois.

The restless nature of many

of the warriors of those tribes had been

greatly worked upon

by Black Hawk and his co-agitators, and

it required the most

heroic efforts to bring them to reason

and restrain them from

war. To this task Keokuk proved himself

equal. He called

a council of the warriors of the Sac and

Fox nations, and when

they were assembled spoke to them as

follows:

"Braves, I am your chief. It is my

duty to rule you as

a father at home, and to lead you to war

if you are determined

to go; but in this war there is no

middle course. The United

States is a great power, and unless we

conquer that great na-

tion we must perish. I will lead you

instantly against the

whites on one condition-that is, that we

shall first put all our

women and children to death and then

resolve that, having

crossed the Mississippi, we shall never

return, but perish among

the graves of our fathers rather than

yieldto the white man."

It would be difficult to find in all

oratory more heroic words

or more determined sentiments than

these; and they had the

desired effect on the minds of a large

majority of the assembled

warriors and influenced them to abandon

their war purposes.

A small number, however, adhered to

Black Hawk, and with

him crossed the Mississippi into

Illinois and began their foray

but were soon subdued and Black Hawk

himself made a prisoner.

|

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their Monuments. 11

Although this raid of Black Hawk and his followers was of short duration, for the time it greatly disturbed the settlers in northern and western Illinois, and was remarkable for the num- ber of distinguished men that it called into active service for its suppression. Among those who served either as regulars in the army of the United States or as officers of volunteers were |

|

|

|

Major-General Winfield Scott, General Atkinson, President Zachariah Taylor, Major-General Robert Anderson, General Jefferson Davis, General David Hunter and Abraham Lincoln. These are some of the most distinguished names in our national history. After the capture of Black Hawk, Jefferson Davis, then a young lieutenant in the United States Army, was appointed to take him and other prisoners to Washington and thence to- |

12 Ohio Arch. and His.

Society Publications.

Fortress Monroe, where he was confined

for a time as a pris-

oner of war, and where Jefferson Davis

himself, thirty-three

years later, was confined for a time for

treason against his

country.

Subsequent to the Black Hawk War, Keokuk

removed with

his tribe from Iowa to the territory of

Kansas, where he died

in 1848. A marble slab was placed over

his grave, which marked

the place of his burial until 1883 when

his remains were ex-

humed and brought back to the City of

Keokuk by a committee

of citizens appointed for that purpose

(Dr. J. M. Shaffer and

Judge C. F. Davis), and interred in the

public park, where a

splendid and durable monument was

erected by voluntary con-

tribution to designate the final resting

place of this noted chief.

In addition to this commendable act on

the part of the citi-

zens of Keokuk, a further lasting mark

of respect has been paid

to him by placing a bronze bust of him

in the marble room of

the United States Senate at Washington.

There is also a portrait of Keokuk

painted by George Catlin

in 1832, now in the Smithsonian

Institution, having been placed

there in 1879 through the generous

donation of Mrs. Joseph Har-

rison, of Philadelphia, who became the

owner of the entire "Cat-

lin Collection," including the

portrait of Keokuk. There are

about three hundred portraits of Indians

in this collection, all

of which were donated by Mrs. Harrison

to the Smithsonian

Institution, and more than any one collection

now existing pre-

serves the features and dress of the

Indian race.

The splendid collection of portraits of

Indian chiefs and

warriors painted by that celebrated

artist, Charles B. King, and

secured by the war department about 1830, known as the

"King

Collection," consisting of one

hundred and forty-seven portraits,

was destroyed by the disastrous fire

which occurred in the Smith-

sonian Institute January 24, 1865. The

celebrated "Stanley Gal-

lery," almost if not quite equally

as valuable, was destroyed at

the same time. These were two of the

most important collec-

tions of Indian portraits ever painted

and in their destruction

the features of many noted chiefs and

warriors were lost

and can never be correctly restored. The

first named of these

collections belonged to the government,

but the "Stanley Gal-

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their

Monuments. 13

lery" was Mr. Stanley's private

property, temporarily deposited

in the Smithsonian Institute.

The efforts to collect galleries of

portraits of representa-

tives of the Indian race have been

singularly unfortunate. The

late P. T. Barnum made a special effort

to collect a gallery of

the portraits of noted members of the

Indian race, and he suc-

ceeded through many years of effort in

collecting one of the

finest galleries of portraits of the red

race that has ever been got-

ten together. Many distinguished artists

contributed their best

efforts upon portraits which became the

property of Mr. Barnum.

The collection was destroyed by fire,

along with his entire

museum, at the corner of Ann street and

Broadway in the City

of New York, July 13, 1865, just six

months after thedestruc-

tion of the King and Stanley collections

in the Smithsonian In-

stitute fire. Thus the three finest

collections of Indian portraits

in existence were destroyed within six

months. The "Catlin

Gallery," the most extensive and

valuable of any now in exist-

ence, passed through two fires and was

greatly damaged, but not

entirely destroyed, and the damage has

in large measure been

repaired.

This collection has had a singular

history. The portraits

were all the work of Mr. Catlin himself,

who was a most inde-

fatigable artist. His collection was

first exhibited in New York,

Philadelphia and Boston in the years

1837, 1838 and 1839. In

1840 he took it to London, where it was

on exhibition in various

cities in England until 1844. He then

took it to Paris, where

it was on exhibition until 1848, when he

was compelled to leave

Paris on account of the revolution

occurring in that year. He

took his collection back to London,

where it remained on ex-

hibition until 1852, when Mr. Catlin

came to financial ruin

through unfortunate speculations. The

collection was seized to

satisfy creditors and finally fell into

the hands of Mr. Joseph

Harrison, Jr., a wealthy and cultivated

gentleman of Philadel-

phia, who had generously assisted Mr.

Catlin in his financial

distress. Subsequently Mr. Harrison had

the collection boxed

and shipped back to Philadelphia, where

it was stored in various

warehouses and remained neglected and

forgotten for twenty-

five years and until 1879, when it was

brought to light in a

14 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

damaged condition. In the meantime Mr.

Harrison had died

and when the collection was discovered

Mrs. Harrison made a

gift of it to the Nation and it was

placed in the Smithsonian

Institute, and is now the only important

collection of original

portraits of Indians in existance.

But Keokuk has received a more noble and

enduring monu-

ment than canvas or marble could secure.

On the west bank

of the Mississippi River, at its

junction with the Des Moines

River, on an elevated bluff overlooking

the magnificent valleys

of both rivers and commanding a view of

the territory of the three

great states of Iowa, Illinois and

Missouri, stands the beautiful

and important City of Keokuk, named for this

noted chief. This

city, where his ashes now repose, was

the center of the territory

originally occupied by the Sac and Fox

nations, of which he

was the most celebrated chief. The

citizens of Keokuk have

surely done themselves honor in honoring

as they have the name

and memory of a man who was the best

representative of the

race that preceded them in the occupancy

of that portion of

the country.

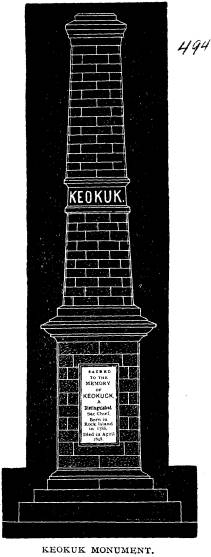

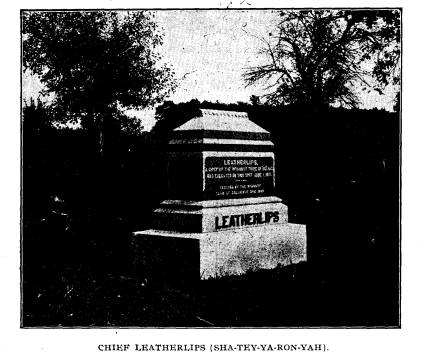

LEATHERLIPS.

The next monument in the order of time,

erected to the

memory of an Indian chief, was that of

Leatherlips (Sha-tey-ya-

ron-yah), on the spot where he was

executed by people of his

own race, June 1, 1810.

The exact spot is on the east bank of

the Scioto River in the extreme

northwest corner of Perry town-

ship, Franklin county, Ohio, about

fifteen miles northwest from

the City of Columbus. This chief was in

camp there at the

time, accompanied only by one of the

hunters of his tribe, when

six Indians, supposed to be of the

Wyandots of Detroit, led by

Round Head, suddenly appeared at his

camp and informed him

that he had been tried and found guilty

of witchcraft and sen-

tenced to death. Resistance was useless

and he submitted to his

fate with dignity and fortitude. His

execution was witnessed

by William Sells, a white man, and a

graphic account of the

dreadful occurrence has been published

in the "Hesperian" by

Ottaway Curry, one of the editors of

that publication, who ob-

tained the account from Mr. Sells. It

was also published in

|

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their Monuments. 15

Drake's Life of Tecumseh, and again quoted in an historical address by Col. Samuel Thompson, of Columbus, Ohio, before the Wyandot Club at the Wyandot Grove, September 18, 1887, and has been widely published in other ways. Where the pre- tended trial for witchcraft was had is not known; but it was the general belief that the whole plan for the taking off of this old chief was devised by Tens-kwan-ta-waw (the Prophet), |

|

|

|

brother of Tecumseh, who had his headquarters at that time on the Tippecanoe River in northern Indiana. He was at that time endeavoring to incite discontent among the Indians and to lead them into war. He was constantly being visited by discontented and evil-minded Indians from the various tribes, and among them some of the Wyandots from about Detroit, and it was supposed that from there the party came through the wilder- ness and found Leatherlips at his temporary camp on the Scioto. |

16 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

The real cause of his taking off was

that he was firmly opposed

to the plans of Tecumseh and the

Prophet, and with Crane and

other well-disposed chiefs was holding

the Wyandots of Ohio

in the lines of peace and keeping them

steadfast in the observ-

ance of their treaty obligations.

The execution of Leatherlips at that

particular point has

accidentally associated his name with

another name of great

and permanent historic interest. About the

middle of the last

century there was born of a noble

Lithuanian family a Polish

patriot, Thaddeus Kosciusko, whose name

will be forever held

dear by liberty-loving people

everywhere, and especially by Amer-

icans. He was educated in the best

military schools of Europe

and became an officer in the Polish

army. At the beginning of

our Revolutionary War he came to this

county to assist the

people of the colonies in their struggle

for independence. He

served during that entire war with great

fidelity and distinction,

a part of the time on the staff of

General Washington as chief

engineer. At the close of that war he

returned to his native

country and was for many years the most

conspicuous figure

in the long and desperate struggle which

Poland maintained

against the combined powers of Russia,

Prussia and Austria.

At last he was defeated, the Polish army

destroyed and he was

carried, wounded and a prisoner, to St.

Petersburg. Poland

suffered dismemberment. After two years

of imprisonment the

death of Queen Catharine of Russia

occurred and Kosciusko

was restored to liberty and his sword

was tendered him by the

new Emperor Paul, but he declined it,

saying that he had no

need of it, as he had no country to defend.

Subsequently (1797)

he re-visited this country and was

everywhere joyfully received

by a grateful people. Congress voted him

honors and lands,

and it so happened that the lands

bestowed upon him were lo-

cated upon the east bank of the Scioto

River in the northern

part of Franklin county, Ohio. It was on

these lands in this

then wilderness that Leatherlips was in

camp when his death

was decreed and here he was executed,

and the virgin soil

which a grateful people had bestowed

upon the liberty-loving

Kosciusko drank the blood of Leatherlips

and there his ashes

repose to-day.

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their

Monuments. 17

On the spot where he was executed and

buried the Wyandot

Club, of the City of Columbus, in the

year 1888, erected a Scotch

granite monument to his memory,

sarcophagus in design. This

club consists of seventeen members,

which number cannot be

increased. It was organized about twenty

years ago for social

purposes, but incidentally the members

have taken an interest

in historic matters pertaining to former

occupants of this portion

of the country.

Some years ago the beautiful Wyandot

Grove, on which is

the celebrated Wyandot Spring, was in

danger of passing into

hands not likely to preserve it. To

prevent this and insure pro-

tection and perpetuation of this noble

grove and spring the club

purchased the grounds, containing forty

acres of land, and

erected thereon a beautiful stone club

house. This grove is

situated on the west bank of the Scioto

River, nine miles north-

west from the City of Columbus. The

spring, which has always

been known from the earliest settlement

as the "Wyandot

Spring," flows out of the limestone

formation at this place in

great volume and is of historic

interest. It was the favorite

stopping place for the Indians and

probably for their predeces-

sors in the occupancy of this portion of

the country on their

way up and down the Scioto River, either

in canoes or on the

trail. The old Indian trail, from the

mouth of the Scioto River

to the Sandusky Bay, passed immediately

by this spring. As

long as the Indians remained in Central

Ohio this continued to

be a favorite stopping place with them

and has also been a place

of resort by the white people ever since

the first settlers ap-

peared along the upper Scioto.

The place where Leatherlips was executed

is six miles north

from the Wyandot Grove, on the opposite

bank of the river. The

spot where this dreadful occurrence took

place has always been

well known to the white settlers in the

neighborhood, and the

late J. C. Thompson, who owned and

occupied the land for

fifty years preceding the purchase by

the Wyandot Club, had

always kept the place marked and

carefully guarded from dese-

cration.

In 1888 the members of the club

purchased an acre of ground

where the execution took place and

surrounded it with a most

Vol. IX-2.

18

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

substantial stone wall and had it

dedicated forever for burial pur-

poses. The monument stands upon the

summit of the east

bank of the Scioto River and about

fifteen rods from the river's

edge at a height of about fifty feet

above the waters of that

stream. The land slopes gradually and

gently from the monu-

ment to the river's edge. The view from

the monument, both

up and down the Scioto at that place, is

one of the most pic-

turesque and beautiful to be found

anywhere on that river. The

grounds are kept in good order and the

place is visited yearly

by many hundreds of people.

When the monument was erected the story

of Leatherlips

and his sad fate had been largely

forgotten by the older genera-

tion, most of whom had passed away, and

had not become gen-

erally known to the younger generation.

The erection of the

monument at once created a wide and

active interest in the pub-

lic mind, and has tended greatly to

widen information not only

in regard to this particular event, but

as to Indian history gen-

erally.

Both Kosciusko and Leatherlips have

obtained enduring

monuments in very unusual and unexpected

ways. The former

saw the liberties of his country

destroyed and his territory par-

titioned among the great powers of

Europe, and himself died

in exile, but his liberty-loving

countrymen brought his remains

back to his native land and erected over

him a mighty mound

of earth which was collected by

patriotic hands from all the

great battle fields of Poland.

Leatherlips had no countrymen

to raise a monument to him. His tribe

had perished from the

earth. There was no one even of his race

to pay him honor or

do ought to preserve his memory, and it

was thought by the

members of the Wyandot Club, which bears

the name of his

tribe, that a suitable monument on the

spot where he was ex-

ecuted would greatly tend to perpetuate

his memory and at the

same time show that the white race was

not wholly indifferent

to the courage and virtues of a man who,

although he was born

a "savage" and lived the wild

life of the forest, yet had great

and noble qualities. A Scotch granite

monument was therefore

procured from Aberdeen, Scotland, and

placed upon the spot

Concerning Indian Chiefs and

Their Monuments. 19

where eighty years before he had been so

cruelly murdered and

obscurely buried in the depths of the

then wilderness of Ohio.

There is every reason to believe that

the death of Chief Crane

was included in the purposes of those

who planned the death

of Leatherlips, and that he would have

fallen a victim of the

conspiracy if he could have been found

separated temporarily

from his tribe, as was Leatherlips. The

truth of course cannot

now be definitely ascertained, but as

Crane was the most im-

portant and influential chief of his

tribe and equally determined

with Leatherlips to restrain his tribe

from war, it may be con-

sidered as certain that the conspirators

would have dispatched

Crane if the opportunity had been

afforded, as it was in the

case of Leatherlips.

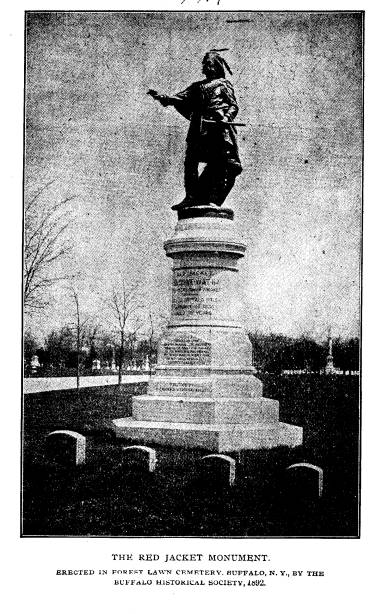

RED JACKET.

The next in order of time was the

mounment to the great

Seneca chief, Red Jacket (Sagoyewatha,

"The Keeper Awake"),

which was erected to his memory and that

of five other chiefs

and nine warriors of the Seneca nation

in Forest Lawn Cemetery,

Buffalo, N. Y., June 22, 1892. Red Jacket was born at Seneca

Lake, New York, in 1752, and died on the

Seneca Reservation,

near Buffalo, January 20, 1830. He was

present, as we have

seen, at the burial of Chief Crane at

Upper Sandusky in 1818,

and was the most conspicuous figure in

that assemblage of

chiefs and warriors. His fame is that of

a statesman and orator

rather than as a warrior, as he came

into prominence after the

period of the long and bloody wars in

which his tribe had been

concerned. He was, however, in several

respects one of the

most noted chiefs of modern times, and

certainly the most noted

among the Six Nations of the Iroquois.

As to his personal

appearance he was described as a

"perfect Indian." He was a

perfect Indian not only in appearance,

but in dress, character

and instinct. He refused to acquire the

English language and

always spoke his native tongue. He

dressed with much taste

in the Indian costume; "upper

garments blue, cut after the

fashion of the hunting shirt, with blue

leggings, very neat moc-

casins, a red jacket and a girdle of red

about his waist. In form

he was erect, but not large. His eye was

fine, his forehead lofty

and capacious, his bearing calm and

dignified." He had an un-

|

20 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications. |

|

|

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their

Monuments. 21

alterable contempt for the dress of the

white man, and also an

unalterable dislike for missionaries. In

answer to a proposal

to send missionaries among his people he

said:

"We also have a religion, which was

given to our fore-

fathers and has been handed down to us,

their children. We

worship in that way. It teaches us to be

thankful for all the

favors we receive, to love each other

and to be united. We never

quarrel about religion.

"The Great Spirit has made us all,

but He has made a differ-

ence between his white and red children.

He has given us

different complexions and different

customs. To you He has

given the arts. To these He has not

opened our eyes. We know

these things to be true, since He has

made so great a differ-

ence between us in other things, why may

we not conclude that

He has given us a different religion,

according to our understand-

ing. The Great Spirit does right; He

knows what is best for

His children; we are satisfied.

"We are told that you have been

preaching to the white

people in this place. These people are

our neighbors; we are

acquainted with them; we will wait a

little while and see what

effect your preaching has upon them. If

we find it does them

good, makes them honest and less

disposed to cheat Indians,

we will then consider again of what you

have said."

On another occasion, speaking of the

missionaries, he said:

"These men know we do not

understand their religion;

we cannot read their book. They tell us

different stories about

what it contains and we believe they

make the book to talk to

suit themselves. The Great Spirit will

not punish us for what

we do not know. He will do justice to

his red children. These

black coats talk to the Great Spirit and

ask for light that we

may see as they do, when they are blind

themselves and quar-

rel about the light which guides them.

These black coats tell

us to work and raise corn; they do

nothing themselves and

would starve to death if somebody did

not feed them. All they

do is to pray to the Great Spirit; but

that will not make corn

or potatoes grow. They have always been

ready to teach us

how to quarrel about their

religion."

22 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

In 1818 the celebrated artist, Charles

B. King, painted a por-

trait of Red Jacket when on a visit to

Washington City. It was

one of the "King Collection,"

owned by the government, and

which was destroyed by fire in the

Smithsonian Institution Jan-

uary 24, 1865.

In 1849 the eminent actor, Henry

Placide, caused a marble

slab, with a suitable inscription, to be

placed at the head of Red

Jacket's grave. This was, however,

largely destroyed by reck-

less and thoughtless relic hunters. What

is left of it is now

deposited in the rooms of the Buffalo

Historical Society at

Buffalo, New York. The place of his

original interment was

in the old Mission Cemetery at East

Buffalo, which, through

neglect and time, came to be a common

pasture ground for cat-

tle and was in a "scandalous state

of delapidation and neglect."

In 1852 an educated Chippeway, named

Copway, delivered

a series of lectures in Buffalo, in

which he called attention to

the neglected grave of Red Jacket. A

prominent resident of

Buffalo, Mr. Hotchkiss, lived near the

place where Red Jacket

was buried and he, together with Copway,

exhumed the remains

and placed them in a cedar coffin, which

he placed in his house.

Hotchkiss' motives were good, but the

Indians then living in

the neighborhood, on discovering that

the remains had been

removed, became greatly excited and made

angry demonstrations

against him. The remains were then given

over to Ruth Ste-

venson, a stepdaughter of Red Jacket,

who retained them in

her cabin for some years, and finally

secreted them in a place

unknown to any person but herself. After

some years, when

she had become advanced in age, she

became anxious to have the

remains of her stepfather receive a

final and known resting

place, and with that view October 2,

1879, she delivered them

to the Buffalo Historical Society, which

society assumed their

care and custody and deposited them in

the vaults of the Western

Savings Bank of Buffalo, where they

remained until October

9, 1884, when the final interment was

made in Forest Lawn

Cemetery at Buffalo.

The splendid monument which now marks

the spot was

not completed for some years after the

interment. The Buf-

falo Historical Society selected a noble

design for the monu-

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their

Monuments. 23

ment, but after expending a large sum of

money on its con-

struction was crippled for means to

bring it to completion. This

embarrassment was finally removed by the

act of a generous

and noble woman, Mrs. Huyler, of New

York City, who, with-

out suggestion or solicitation, came

forward and gave her check

for ten thousand dollars, that being the

sum necessary to com-

plete the work so worthily begun. The

society was anxious to

make public the name of this generous

lady, but she preferred

otherwise, desiring that the members of

the Buffalo Historical

Society should have the credit of

completing the splendid work

which they had designed and set in

motion. The name, how-

ever, has long been an open secret,

although we think it has

never before been published. The time

has now come, how-

ever, when no harm can come by openly

connecting Mrs. Huy-

ler's name with the noble enterprise

which her generous dona-

tion brought so happily to completion.

No one American of

whom we have knowledge has contributed

so generously to an

effort on the part of the white race to

perpetuate the history

and memory of the red race, now

practically passed away.

The unveiling of this monument took

place June 22, 1892,

and it is and will be for all time a

sterling credit to the designers

and promoters of this tribute to the

memory of Red Jacket and

other chiefs of the Seneca Nation. Along

with the remains of

Red Jacket there was also interred at

the same time the remains

of five other Seneca chiefs and nine

unknown warriors, their

remains having been removed from the Old

Mission Burying

Ground near Buffalo, where Red Jacket

was originally buried.

So that the monument commemorates not only

the great Chief

Red Jacket, but has the wider

significance of being a tribute to

the memory of the Seneca Nation, which

occupied that region

of beauty and grandeur about the Niagara

River and there

worshipped and waged war as far back as

we have any history

or tradition of them.

The names of the other chiefs whose

ashes were re-interred

and now repose by the side of Red Jacket

beneath the shadow

of this splendid monument were:

24 Ohio

Arch. and His. Society Publications.

First: Young King (Gui-en-gwah-toh),

born about 1760

and probably a nephew of Old King,

renowned in the annals

of the Seneca Nation.

Second: Captain Pollard (Ga-on-dowau-na;

Big-Tree),

who was a Seneca Sachem and said to be

only second to Red

Jacket as an orator and superior to him

in morals, "being liter-

ally a man without guile and

distinguished for his benevolence

and wisdom."

Third: Little Billy (Jish-ge-ge, or

Katy-did, an insect),

also called "The War Chief,"

died December 28, 1834, at Buf-

falo Creek, New York, at a very advanced

age. He was one

of the Indian guides who accompanied

Washington on his mis-

sion to Fort Duquesne during the old

French and Indian war.

Fourth: Destroy-Town (Go-non-da-gie;

meaning "he de-

stroys the town"), was noted for

the "soundness of his judg-

ment, his love of truth, his probity and

his bravery as a warrior."

Fifth: Tall Peter (Ha-no-ja-cya), who

was one of the lead-

ing chiefs of his nation and led a

useful and exemplary life.

He also was buried in the Old Mission

Cemetery with the other

chiefs before mentioned, and his remains

were exhumed and re-

interred with his fellow chiefs and

warriors.

By the commendable and most praiseworthy

action on the

part of the Buffalo Historical Society,

the names of all these

once celebrated and worthy chiefs and

sachems have been res-

cued from that oblivion which has fallen

upon the names and

memories of almost all of the great and

influential men of their

race.

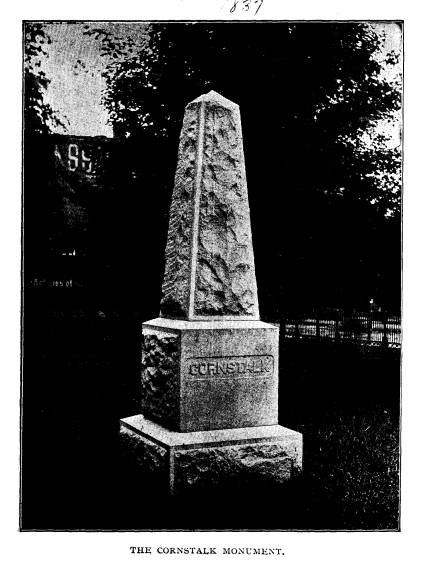

CORNSTALK.

The next monument in the order of time

was that of Chief

Cornstalk, a great Shawnee Sachem and

warrior, erected at

Point Pleasant, West Virginia, in

October, 1896. This monu-

ment stands in the Court House yard and

was placed there by a

few enterprising and generous residents

of Point Pleasant,

prominent among them being Hon. Lon T.

Pilchard, Hon. C. E.

Hogg, Hon. John E. Beller, Capt. John R.

Selbe, Mr. F. B.

Tippett, Col. Thomas Mulford and others.

|

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their Monuments. 25 |

|

|

26 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

On the occasion of the unveiling of the

monument Hon. C.

E. Hogg delivered an address replete

with eloquence and his-

torical statements, in the course of

which he said:

"Who was this man that, after the

lapse of more than one

hundred years since falling to sleep in

the lands of his fore-

fathers, that these proud and noble

people should assemble here

beneath the shadows of this aged temple

of justice on this

autumnal day to do honor to his life and

character? History

answers that he was a son of the

Shawnees, a child of the forest

and of nature; an Indian, but a warrior

and chieftain; wise and

composed in council, but fierce and

terrible in war. * * *

God had raised him up to be the leader

of his people and the

Creator had endowed him with splendid

intellectual faculties.

* * * He was a great orator, a man of

transcendant elo-

quence; but the fame of Cornstalk will

always rest upon his

prowess and generalship at the battle of

Point Pleasant, fought

on the 10th day of October, 1774, and

the ground upon which

we are now gathered was the scene of the

thickest of the fight,

and where the Death Angel struggled the

hardest to seize upon

his victims. * * * This battle so

momentous in its con-

sequences was not the result of

accident. It was planned and

carried out by the commander and his

braves with consummate

skill and far-sightedness. History says

that this distinguished

chief and consummate warrior proved

himself on this eventful

day to be justly entitled to the

prominent position which he

occupied. * * *"

"Never did men exhibit more

conclusive evidence of bravery

in making a charge and fortitude in

sustaining an onset than

did these undisciplined and unlettered

soldiers of the forest on

the field of battle at Point Pleasant in

the dark days of our

country, more than a century ago. Such

was the foe our white

brethren had to meet in battle on that

historic day. But by skill

in arms, valor in action and strategy in

plan as nightfall began

to approach and the great orb of day to

hide his face from the

terrible scene of carnage and death the

almost invincible enemy

withdrew from action and victory perched

upon our arms.

Not a great while after this famous

battle, indeed before its

disasters had ceased to echo in the

savage ear, a mighty coalition

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their

Monuments. 27

was forming among the Indians northwest

of the Ohio River for

the purpose of waging war against the

colonists and the Ameri-

can patriots to further the cause of

British aggression and the

assent of the Shawnees alone was wanting

to conclude its per-

fection. The distinguished sachem, whose

memory we are glad

to honor to-day, at the head of the

great nation of the Shawnees,

was opposed to an alliance with the

British and anxious to main-

tain friendly and cordial relations with

the colonists. All his

influence and all his energies were

exerted to prevent his brethren

from again making war upon our people,

but all his efforts to

stay its tide seemed to be in vain, so

determined were his people

to again enter upon the wild theater of

war. In this posture

of affairs he again came to this place,

then in command of Capt.

Matthew Arbuckle, on a mission of

friendship and love to com-

municate the hostile preparations of the

Indians and that the

Shawnees alone-Cornstalk's people-were

wanting to render

a confederacy complete and that the

current of feeling was run-

ning so strong among the Indians against

the colonists that the

Shawnees would float with the stream in

despite of his endeav-

ors to stem it and that hostilities

would commence immediately."

These extracts more eloquently and truly

portray the life

and character of Cornstalk than any

words of mine could do.

The story of Cornstalk and his sad fate,

and that of his son,

Ellinipsico, and Red Hawk, the brilliant

young chief who ac-

companied Cornstalk on this friendly

mission to Point Pleasant,

has been so often and sorrowfully told

that it is not our purpose

to repeat it here, further than to say,

that it was a most unfortu-

nate and inexcusable error to detain

them as was done in the

camp, which they had entered with

friendly feelings and with

the highest and best motives.

A day or two after their unfortunate

detention it so hap-

pened that some roving Indians prowling

in the neighborhood

of the camp killed a white man. At least

that was the report,

and thereupon the infuriated soldiers

under Captain Arbunckle,

in despite of his best efforts to

restrain them, rushed upon Corn-

stalk and his son and Chief Red-Hawk and

most cruelly mur-

dered them. It always has been and

always will be considered

one of the most inexcusable and

unfortunate murders in the his-

28 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

tory of our contact with the red

race. It destroyed at once and

necessarily the only hope of

reconciliation and peace between

the white settlers south of the Ohio

River and the Indian tribes

north of it. This dreadful occurrence

was in the month of

May, 1777, and was followed by a

succession of wars, forays

and murders down to the battle of

"Fallen Timbers," in 1794,

during which time many thousands of

white men, women and

children, and many thousands of the red

race of all ages and

conditions perished at each other's

hands.

The dreadful character of the crime was,

if possible, height-

ened by the death of the brilliant young

Chief Ellinipsico, son

of Cornstalk. The old chief went

voluntarily into the camp

of the white men, but the son was

deceived and treacherously

misled and trapped to his death. He was

enticed across the

Ohio River by deceit and fraudulent

pretenses of friendship and

immediately imprisoned with his father

and Red Hawk and suf-

fered death at the same time with them.

There never has been

and never can be any excuse or

palliation for the murder of this

young chief and no one event in the

history of those bloody times

so much enraged the vindictive spirit of

the Indian tribes, partic-

ularly of the Shawnees. It can never be

known how many

deaths of white men, women and children

during the next twenty

years were owing to this treachery and

murder, but it is certain

that they were legion.

It is an inspiring thought that some

justice sometimes at

least comes around to the memory of

those who have been cruelly

wronged and such has been the case with

Cornstalk. One hun-

dred and twenty years after he had been

cruelly murdered by those

whom he was trying to befriend and

protect, a suitable and endur-

ing monument was raised to his memory by

a few generous-

minded white men on the spot where he

fought one of the great-

est battles in all Indian warfare, and

where he, three years after-

wards, gave up his life while engaged in

a friendly and noble

mission for the benefit and protection

of the white race, as well

as that of his own.

|

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their Monuments. 29

SHABBONA. We have now mentioned all the monuments which have been actually erected to individual Indians of which we have knowledge; but it is proper to add that another monument has |

|

|

|

been proposed and is now being urged for the great Pottowatto- mie Chief Shabbona or Sha-bo-na (meaning, built like a bear). This celebrated chief died near Morris, Grundy county, Ill., July 17, 1859, and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery at Morris, Ill. His pall-bearers were all white men, of whom but one of them (Hon. P. A. Armstrong) is living at the present time. He was well acquainted with this old chief and of him he has said that |

30 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

"He was as modest as he was brave

and as true to the dictates

of humanity as the sun."

Mr. Armstrong is the president of an

association organized

for the purpose of erecting a monument

to this noted chief.

Shabbona went with his tribe from

Illinois in 1835 to the terri-

tory west of the Mississippi, but years

afterwards returned to

the State of Illinois, where the

Government of the United States

had bestowed upon him lands in Grundy

county, for his services

during the Black Hawk war, and he

remained in Grundy county

until he died. That he was cheated out

of these lands by un-

scrupulous white men before his death is

a sad and mortifying

fact, but it is not germane to our

present purpose. We desire now

only to recall briefly the merits of

this brave man and his claims to

recognition by the white race. He was

second in command of the

Indian forces under Tecumseh at the

"Battle of the Thames" in

1813, and was in command of the Indian

forces after Tecumseh

fell. The result of that battle was such

as to convince him that no

further wars could be successfully waged

by the Indians against

the white race, and he determined

thereafter to refrain from

war, and when in 1832 Black Hawk

appealed to him to join

forces with him he not only turned a

deaf ear to his entreaties,

but exerted himself to the utmost to

warn and protect the white

settlers against the contemplated foray

of Black Hawk. Black

Hawk said to him by way of inducement to

join in his purposes:

"If you will permit your young men

to unite with mine I will

have an army like the trees in the

forest and will drive the pale-

faces before me like autumn leaves

before an angry wind," to

which Shabbona replied: "But the

palefaces will soon bring

an army like the leaves on the trees and

sweep you into the ocean

beneath the setting sun." Seeing,

however, that Black Hawk

was determined upon war and bloodshed,

he slipped away from

the council and by most extraordinary

efforts hastened himself

in one direction while sending his son

in another, and thus suc-

ceeded in warning the white settlers of

their impending danger

and saved most of them from the

slaughter which otherwise

would have fallen upon all. Most of

those who lost their lives

in that foray had refused to heed the

warnings which Shabbona

had given them. Afterward he acted as

guide for General At-

Concerning Indian Chiefs and Their

Monuments. 31

kins in his pursuit of Black Hawk

through the Winnebago

swamps. For these acts and efforts he

was afterwards tried by

his tribe and found guilty of aiding and

abetting the enemies of

his people, and the title of chief was

taken away from him and he

was ever afterwards treated as a traitor

to his tribe and race.

It has been said of him by one of the

most intelligent and

well-informed writers, concerning this

old chief, that: "History

records the deeds of no champion of

pure, noble, disinterested and

genuine self-sacrificing humanity

equalling those of this untu-

tored, so-called savage, Shabbona."

It is to be most sincerely hoped that

the efforts of the asso-

ciation to erect a monument to this old

chief may soon be ended

in success, for surely he deserves of

the white race for whom

he sacrificed everything that was dear

in life, and by some of

whom he was most deeply wronged, that

they should rescue his

name permanently from oblivion and show

to the world that his

worthy life and self-sacrificing deeds

have not been and shall

not be forgotten.