Ohio History Journal

|

MATTHIAS LOY, Leader Of Ohio's Lutherans

by C. GEORGE FRY |

|

|

|

Among the names of the pioneers who labored to establish a strong Lutheran Church in Ohio, that of Matthias Loy deserves a prominent place. At the time of his death in 1915 he was regarded as "one of the most distinguished theologians of the Lutheran faith in the United States,"1 and in his long and productive life he had been a "Churchman of varied attainments and wide usefulness: pastor, professor, editor, author, [and] church leader."2 As an educator, he taught theology and related subjects at Capital Uni- versity for almost half a century, earning a reputation as the "grand old man" of the school.3 For nearly a decade he served as president of Capital. As a journalist, Loy edited the official periodical of the Evangelical Lutheran Joint Synod of Ohio, the Lutheran Standard, from 1864 until 1890. Con- sidered a "religious author of note,"4 he composed hymns, compiled litur- gical formulas and catechisms, published numerous theological treatises, and translated the works of Luther and other sixteenth century reformers from Latin and German into English. For thirty-two years Loy was presi- dent of the Joint Synod, and under his direction it expanded from its original home in the upper Ohio Valley to establish congregations in more than half the states of the Union and in Canada and Australia. Esteemed as "one of the greatest conservative leaders of the Lutheran Church,"5 Dr. Matthias Loy did more than any other individual to affect the development, doctrine, and destiny of Ohio Lutheranism during the latter half of the nineteenth century.

NOTES ON PAGE 267 |

184 OHIO HISTORY

Little is known of Dr. Loy's early years

or his forebears except those

details that can be found in his

autobiography, Story of My Life.6 His

earliest American ancestor was his

father, Matthias, a German immigrant

of limited means and learning, who

arrived in the United States, presumably

at Philadelphia in 1817 from the Grand

Duchy of Baden.7 As an indentured

servant, he worked three years to pay

off his passage before he moved to

the newly-founded capital of

Pennsylvania at Harrisburg to obtain employ-

ment as a cabinetmaker.8 There

he met Christina Reaver, an immigrant from

the Kingdom of Wurttemberg, to whom he

was married on October 18, 1821.9

Miss Reaver had received an elementary

education in a parochial school in

Germany and was a woman of a "deep

Lutheran piety," characteristic of

her Swabian homeland. By 1827 the Loys

had settled as tenant farmers

on a lovely but lonely homestead in the Blue

Mountains of Cumberland

County, about fourteen miles from

Harrisburg. It was there that Matthias

Loy was born on March 17, 1828, the

fourth of seven children of the family

of Matthias and Christina Loy in a

period of fifteen years.10

Loy's childhood was filled with poverty,

loneliness, and religious piety.11

Though his father was a conscientious

craftsman, he was frequently unable

to supply the needs of his family

because he was too timid and too un-

skilled in the use of English to demand

payment from his debtors for his

labors. Living in an unfrequented

region, one of the family's few con-

tacts with the outside community was

through the elder Loy, who, once

or twice annually, made a trip to

Harrisburg. One time, upon his return

from town, Loy said his father

"brought a toy that even astonished my

mother for its beauty and ingenuity, and

which had cost the sum of ten

cents. I remember how I sought a hiding

place when my father pulled the

string and a cock leaped from the box.

It was amazing."12

Loy's playmates were his brothers and

sisters, and they relied upon their

imaginations to transform the drab

forest home into a fairyland of ad-

venture, building houses of sticks and

stones, erecting castles of snow,

and hunting whortleberries and chestnuts

on the slippery hillside slopes.

Of the world beyond the woods, Loy knew

little, and he later reminisced

that he had not seen a church until he

was six years of age. His mother,

however, taught her children the rudiments

of the Christian religion and

required all of them, with the exception

of an older brother, to be bap-

tized into the Lutheran Church as

infants. The elder brother's baptism

was delayed because an itinerant

Lutheran minister, when requested to

perform the ceremony, declined to do so

because the young man "had be-

come an Anabaptist and was planning to

establish a Baptist sect."13

In 1834, when Matthias was six, the

family moved to Hogestown, a post

village nine miles west of Harrisburg on

the turnpike between Philadelphia

and Pittsburgh. As late as 1876 it

numbered only forty houses, and Loy

described it as "a desolate

hamlet" where "my father thought that he could

make a living . . . . The stagecoach . .

. passed through it with its passengers,

and large six-horse teams hauling

merchandise passed through every day."14

With one hundred dollars earned on the

farm, father Loy bought a

dilapidated log house, the only home

that he ever owned. The Loy children

MATTHIAS LOY 185

now had the advantage of receiving some

formal education in a one-room

school, and Matthias proved to be a

bright pupil, excelling in mensuration,

a branch of mathematics. In the village

the Presbyterians sponsored an

interdenominational Sunday School where

Loy was introduced to the

Christian tradition and the study of

Scripture. He was such a serious church

school scholar that his classmates

nicknamed him "the preacher."

Difficulties soon befell the family.

Three of the seven Loy children died,

and in 1835, when he was seven years

old, he lost his mother. Medical and

burial expenses were impoverishing, and

an elder brother, age eleven, left

home to make his own way in the world. A

fifteen year old sister remained

to keep house until her father

remarried. Matthias became an assistant

to his father in the operation of a

butcher shop in Harrisburg. He was

also hired out to haul bricks from a

local kiln, but, as Loy reported,

As driving a cart was not part of my

education at the time, it was

no wonder that, with a horse incapable

of doing the work as I was

myself, an accident on a steep approach

to the canal to be crossed to

reach the city from the brickyard,

crippled the horse by a fall down

the embankment and drove me home to bed

in despair, without look-

ing after the animal that had tumbled

down.15

Matthias Loy senior married as his

second wife Johanna Morsch, a Ger-

man Lutheran woman of Harrisburg, in

April 1840, and within a year a

son was born to the union.16 Added

domestic responsibilities prompted the

elder Loy to seek to increase his income

by managing a German hotel

and tavern on the south side of the

city. He entrusted its operation to his

wife and children while he worked

elsewhere during the day. Living in

such an environment, Matthias found

himself exposed at the age of twelve

to "gatherings and performances

which even then seemed to me of question-

able propriety."

Plagued with debts and bad fortune,

Loy's father left Harrisburg and

returned to Hogestown where he formed a

partnership in a butchershop

with a German wanderer, who had some

money but no home. Concerning

his father's colleague, the son recalled

that he "was sent to the store nearly

every day to get a quart of rum, and

that his face had a purple hue which

seemed to me unnatural." Because of

such unwholesome circumstances, an

incident occurred in Loy's fourteenth

year that caused him to be sent

away from home. One evening, in his

father's absence, visitors came to

the household. Since their conduct did

not meet with the boy's approval,

Matthias uttered a protest. In response,

his stepmother struck him for his

"impudent interference." When

father Loy returned and learned of his

son's behavior, he was convinced that

the "peace of the family" required

his removal. The boy was then

apprenticed to the printing establishment of

Baab and Hummel in Harrisburg, and he

was never to return to his boyhood

home again.17

During the next six years, Loy mastered

the printer's art and made his

first formal affiliation with the

Lutheran Church. At the age of sixteen

he became obsessed with religious

questions, believing that he "had wan-

dered away so far that God did not seem

near and help did not appear

186 OHIO HISTORY

within my reach."18 In

this period -- 1843 to 1844 -- the Millerite revival

was sweeping the country. William

Miller, a New England farmer of Bap-

tist background, on the basis of certain

passages from the books of Daniel

and The Revelation, had predicted the

end of the world for March 21, 1843.

As the announced date for the Second

Advent of the Messiah approached,

"great meetings were held in churches,

tents, public buildings, and in the

fields and groves, and finally when the

year 1843 dawned the emotions

of the believers were of white

heat."19

The enthusiasm also affected the

Lutherans of Harrisburg, and the

Reverend C. W. Schaeffer of Zion Church introduced

a "New Measure

Revival."20 As a disciple of the

liberal Lutheran divine Samuel Simon

Schmucker, Schaeffer was "a

forcible and impressive preacher, [and] he

brought into especial prominence the

consolations of the gospel from a

heart filled with joy over its promises."21 As the

"protracted meetings"

commenced, Loy presented himself at the

"anxious bench." He remembered

that,

The revival "workers"

whispered into my ears, as I knelt in silence

before the altar, some things which were

meant for my encourage-

ment, but which only left me unmoved

because of their failure to

reach my conscience.

Finally, after participating with

Schaeffer in a class for instruction in re-

vealed truth, Loy found himself in a

state of grace, and resolved to study

for the Lutheran ministry at Gettysburg

Theological Seminary.22

The young convert diligently prepared

himself for college by attend-

ing classes in the classical languages

at the Harrisburg Academy. By the

fall of 1847 he was ready for Gettysburg.23

Then, however, he became

seriously ill with an attack of

"inflammatory rheumatism."24 Loy was ad-

vised to abandon work in the printer's

shop, to stop attending the academy,

and to seek a better climate. At this

juncture a position became available

as a printer for a semi-monthly German

paper published by the United

Brethren Publishing House in

Circleville, Ohio. The responsibilities would

be light, the pay six dollars a week,

and in addition it was hoped that a

move to Ohio would improve his health.25

With the intention of recuperat-

ing and of earning money for the

seminary, Loy left Pennsylvania, hardly

realizing it was his final farewell to

his native state.

For a boy who had never travelled more

than thirty miles from his

place of birth, the trip West by

railway, river boat, and stage coach was

packed with excitement. Loy took the

newly completed Cumberland Valley

Railroad from Harrisburg to

Chambersburg, the "gateway to the West."26

Because of crowded facilities, he had to

wait a day, and then be satisfied

with outside passage on the stage to

Pittsburgh. Riding in the rain and

sleet through the mountains did little

to improve his physical condition.

Relieved to find himself at last in

Pittsburgh, the youth fell in love with

the city, which he would later describe

as "one of our favorite burgs" be-

cause " the people have business

and mind their business, and are not busy-

bodies about other men's matters."27

A relatively peaceful cruise by steam-

MATTHIAS LOY 187

boat down the Ohio and up the Muskingum

River to Zanesville followed.

The only disturbing aspect of this part

of the journey occurred when the

traveller asked the pilot of the ship

how he managed to cross the sandbars

in the river, and the latter replied

that "the only rational way was to put

on more steam and shut his eyes."

Once in the Buckeye State, Loy felt

it was "still in a primitive condition,"

though it had been in the Union for

forty-four years. Because of the almost

impassable condition of the sec-

ondary roads, the overland ride from

Zanesville to Circleville by stage

meant "paying the price and walking

all the way, with special good for-

tune if one was not required to carry

rail to help the coach in swampy

emergencies."28

Loy remained only a fortnight in

Circleville. Almost immediately he be-

came acquainted with the Reverend J. A.

Roof, the minister of the local

Lutheran congregation. Pastor Roof was

impressed with the young man's

longing to enter the ministry and

encouraged him to enroll as a "beneficiary

student" at the theological

seminary of the Evangelical Lutheran Joint Synod

of Ohio located in Columbus. Loy stated,

"I had never heard of such a Sem-

inary and of such a Synod, but that

presented no difficulty to my mind."29

It was arranged that he would print two

numbers of the United Brethren

periodical, receive $24.00 for a month's

labor, and then be released from

his contract. After promptly completing

the work in two weeks, he departed

for Columbus.

The theological school, then located on

South High Street, was the oldest

Lutheran and second oldest Christian

seminary of any denomination west

of the Appalachian Mountains.30 Founded

by the Evangelical Lutheran Joint

Synod of Ohio in 1830, the year of the

three hundredth anniversary of the

Augsburg Confession, the seminary's

first professor was a twenty-seven year

old pastor, Wilhelm Schmidt of Canton.31

He was given this assignment

because he had suited the synod's

requirements for the position as one

who "must have extraordinary

ability and must neither need nor want any

remuneration for his services."32

For a year classes had been held in Schmidt's

home in Canton; but when he followed a

call to Columbus, the school ac-

companied him. By the autumn of 1847,

when Loy enrolled, the seminary

was housed in a two-story brick building

near the old canal,33 just outside

the corporation limits of Columbus,

which was in 1850 a town of 17,882

inhabitants. There were eight to ten

students in the seminary, who were

of American, German, and Swiss

nationalities.34 The curriculum included

the classical languages, Hebrew, Bible,

Livy, Homer, and the Lutheran

Confessions.35 The faculty,

since June 1847, consisted only of the Reverend

W. F. Lehmann, a twenty-six year old

minister from Somerset, Ohio, who

was nicknamed the "Walking Encyclopedia."36

Lehmann taught the sem-

inary courses, conducted a preparatory

academy, and served a Columbus

parish. He was assisted in his

"herculean task" by the Reverend Christian

Spielmann, a native of Baden, who was in

charge of the boarding house

for the seminary. For two years Loy

studied theology, worked for the

Ohio State Journal, and aided in the printing of the Lutheran Standard,

188 OHIO HISTORY

the official publication of the Ohio

Synod. During this time Spielmann in-

troduced Loy to the publication, Der

Lutheraner, which was produced by

C. F. W. Walther as the voice of

"Old Lutheranism" in America.37 Under

the influence of this journal, the young

student came to sympathize with

the strict confessionalism of the

recently-formed Missouri Synod.38

In 1849, after finishing two years of

seminary study, Loy was felt to be

qualified to receive a call. Since there

was a shortage of Lutheran pastors

in Ohio, his name was placed upon the

synod's list of men to be examined

for the ministry, and he was soon asked

to serve a Lutheran-Reformed

"union church," the Zion's

congregation of Delaware.39

"On a rather rough day" in

March 1849, Loy, "an emaciated, pale faced

youth," who had just turned

twenty-one, boarded the stage in Columbus

for the twenty-four mile journey to

Delaware.40 In the middle of the nine-

teenth century, Delaware was a town of

2,075 residents. An exuberant local

editor reported what he believed to be

strangers' reactions to the village:

People from a distance upon arriving

here are struck dumb with as-

tonishment at the sights they behold....

They imagine themselves in

London rather than in Delaware. Marion,

Kenton, Mt. Gilead, Upper

Sandusky and the city of Tiffin sink

into utter insignificance by the

side of Delaware.41

A more temperate appraisal by a member

of the staff of the Cincinnati

Commercial described the community as follows:

The town of Delaware, the county seat of

the county bearing the

same name, though it has been settled

for nearly fifty-years, has none

of that seedy appearance which some of

our old Ohio towns exhibit.

It has quite a fresh and lively

appearance, both in the business quarters

and those devoted to private residences.

The buildings of the citizens present

numerous evidences of the

prevalence of good taste. A large

majority of them are new.

Returning to the American House after an

hour's varied ramble,

the unique impression we gather of the

town is one of agreeable surprise

that so much elegance of improvement

combined with such natural

beauty, exists in a village which has

made so little noise in the world

as Delaware.42

Religiously, the hamlet was dominated by

Methodism, and "people talked

about changing its name to Wesleyville."43

The pride of the community

was the Ohio Wesleyan University,

established in 1842. Nine years later

an editor commented that "this

Institution is in a flourishing condition

and bids fair to outstrip even old

Yale."44 In this university town, Loy

began his career.

The people to whom he was to minister

were descended from "Pennsyl-

vania German" pioneers who,

beginning in 1810 and 1811, had emigrated

to Ohio from Northumberland, Berks, and

other counties of the Keystone

State.45 Within a decade they

had established a Lutheran congregation, but

ties of language, blood, and marriage

drew them close to the German Re-

formed Christians of the county.

Becoming convinced that there was little

real difference between Lutheranism and

Calvinism, German-speaking Prot-

estants of Delaware secured

incorporation from the Ohio General Assembly

MATTHIAS LOY 189

on January 23, 1837, as the "Zion

Evangelical Lutheran and Reformed

Church."46 One of the

leaders in this endeavor was Frederick Weiser, who

could claim the famed frontier scout,

Conrad Weiser, as a forefather. The

Lutherans and the Reformed shared common

worship facilities and fre-

quently the same minister. The

constitution stated that the parish was

"to elect one Teacher [pastor] by a

majority vote, he being in respect

to faith either Lutheran or

Reformed."47 The Lutheran liturgy and the Re-

formed rite were followed on alternate

Sundays. Each "side" had the use

of the church building for one week, on

a rotating basis, beginning on

Thursday, except

We declare that cases of death shall

have preference over the services

of worship, namely, that if a Reformed

corpse should come on a Sunday

when the Lutherans hold service, then

the Lutheran service shall be

postponed to a later time because of the

corpse, and in a similar fashion

the other way around.

Since the union proved satisfactory to

both groups, it was declared in 1847

to be "eternal."48

Loy felt "it would even have been

impossible for me to accept the call

pledging me to treat the Reformed as if

they were Lutherans and no such

obligation was imposed upon me."49

He was called only to minister to the

Lutheran members of the Zion's Church.

His conscience, thus, was not com-

promised, because he had been elected by

the male communicants among

the eighty Lutherans of the Zion

congregation as their pastor after hearing

him preach a trial sermon in the winter

of 1849.50 Loy was convinced that

"unionism," or spiritual

fellowship with the Reformed without prior doc-

trinal concord, was an evil, and he

wrote that "we must rather stand alone

than be partakers of other men's sins."51

Accordingly, he strove to sever

all ties with the Reformed. Within three

years this was accomplished, and

the Lutheran constituents of the Zion's

church organized themselves in Au-

gust 1852 as an independent body under

the name of the "St. Mark Evan-

gelical Lutheran Congregation of the

Unaltered Augsburg Confession."52

Dislike of the Zion church building, which

Loy described as "a reproduc-

tion on a small scale of the barnlike

structures called churches in Pennsyl-

vania," and rising denominational

consciousness prompted the Lutherans

to construct their own house of worship.53

On December 25, 1853, their

new structure was consecrated, Christmas

celebrated, a baptism performed,

Holy Communion observed, and Pastor Loy

was married to Miss Mary

Willey, a native of Delaware County, to

which union were born seven chil-

dren.54

Life in a conservative German-American

Lutheran parish in the mid-

nineteenth century was full of problems.

Money was one of these. It had

been a common practice in the community

for churches to raise funds

through the sale of goods and services.55

Loy condemned such customs be-

cause he was persuaded that cash secured

in any fashion other than by

donations was "the money of the

devil and the world and the flesh." He

saw that there was no selling at St.

Mark's of "fancy articles" or "ice-cream

190 OHIO HISTORY

and strawberries and oysters" or

"pretzels, and cheese and beer," and tickets

for "chances and prizes," or

"theatrical shows and ladies' kisses."56 The

stubborn Pennsylvania Germans were

informed that they were to pledge

to support the church and that the

deacons of the congregation would visit

the membership quarterly to collect the

gifts.57

Sermons were delivered in both English

and German each Sunday at St.

Mark's and for two country congregations

which Loy also served. From

1853 to 1857, therefore, he was

preaching between four and six times a

Sunday.58 While a formulary

of the Ohio Synod suggested that sermons

should last no longer than an hour,

Pastor Loy usually confined his re-

marks to twenty or thirty minutes.59

Communion, a means of grace in the

Lutheran Church, was observed four to

six times annually with the apparent

use of grape juice instead of wine to

counteract the "tippling" or drunken-

ness problem among the membership.60

A traditional parish practice was the

pastoral visit. A call by Dr. Loy

was not a social occasion. When the

parson appeared, the family was sum-

moned together -- the father from his

toils in the field, the mother from

her housework, the children from their

play and chores.61 Assembling in

the parlor, the family fell into a

hushed silence. The minister, dressed in a

black suit and clerical collar and vest,

began the meeting with prayer and

selected readings from the Bible. He led

in the singing of a hymn. A dis-

cussion of the sermon of the previous

Sunday followed. In a manner similar

to that of the Lutheran patriarch, Henry

Melchior Muhlenberg, Loy cate-

chized his parishioners on its content.62

They were to identify the text, name

the principal parts of the address, and

to explain its application to their

lives. He would then ask if they had any

questions concerning the homily,

either as to its subject matter or

vocabulary. If they had not understood

the sermon, he took pains to explain it

to them. Loy then inquired as to

the spiritual condition of the

household. The "Our Father" was prayed, a

benediction was pronounced, refreshments

were served, and the pastor de-

parted for his next appointment.

The influence of Pietism upon the

morality of Ohio's Lutherans was evi-

dent in Loy's concern to "institute

a better discipline in the congregation."

Believing that "sin must be put

away from us, that we may be a holy people,"

he joined with the church council to

enforce what he considered to be ap-

propriate ethical standards.63 The

council and the minister heard and initi-

ated charges against parishioners

suspected of ungodly living.64 The accused

was invited to appear before the council

to give answer. If he did not come,

he received a visit from the preacher.

If the offending brother remained

impenitent, his name was announced to

the congregation and he was allowed

fourteen days in which to make amends.

If repentance failed to occur within

a fortnight, his excommunication was

pronounced from the pulpit.65 Dis-

cipline was enforced against

"heretical teachings," and a pastoral warning

was administered for such "improper

behavior" as patronizing theatrical

shows, circuses, card parties, club frolics,

saloons, and horse races.66 Drunken-

ness was a serious offense and the

treatment of the inebriate was rather

MATTHIAS LOY 191

severe for a German Lutheran church.

Tavern owners and those who sold

beer and ale were not permitted to hold

membership in the parish.67 Adultery

was harshly condemned, though the church

laws against it seem to have

been enforced more frequently against

female offenders than male delin-

quents. A woman found guilty of

unchastity was to confess her sin to the

church council, receive pastoral

absolution, and then to rise before the

congregation on the following Sunday to

make confession and seek for-

giveness.68

Delaware's Lutherans responded to Loy's

leadership, and by 1864 the

average Sunday attendance was 330.69 The

parish had paid its debts, es-

tablished a parochial school, and had

attained a prominent place in the ranks

of the Ohio Synod. The achievements of

Loy were recognized by the synod.

In 1860 he was elected its president and

four years later he was appointed

editor of its publication, the Lutheran

Standard. Earlier, in 1853, Capital

University conferred upon him the

honorary degree of Master of Arts, and

he was invited to teach several days

each week at that institution.70 He was

called to a professorship at Capital in

the spring of 1865.

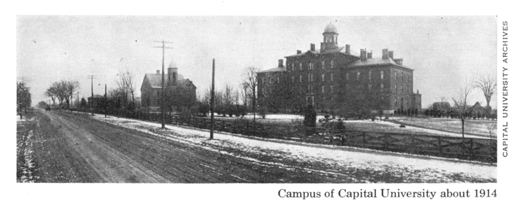

Capital University was established in

1850. The immediate reason for

its formation had been the Joint Synod's

conviction that ministerial can-

didates "must have a better

academic preparation," and, as one historian

suggested, the university was "the

child of the 'German Evangelical Lu-

theran Theological Seminary.'"71 The synod

was also impressed with the

rapid increase of educational

institutions in Ohio, a total of forty-five col-

leges having been founded by 1850.72 A

charter granted on March 2, 1850

incorporated Capital University for the

"promotion of religion, morality,

and learning."73 The

original board of trustees was interdenominational and

included such Columbus citizens of

"good repute for morality, intelligence

and honesty" as Samuel Galloway,

then Ohio Secretary of State; Henry

Stanbery, Ohio Attorney General; Dr.

Lincoln Goodale; Dr. Samuel M.

Smith, Dean of the Starling Medical

School; and George M. Parsons.74

Great expectations were entertained and

the university was to include fac-

ulties of Letters, Law, Medicine, and

Theology.75 A theological seminary

already existed and it was joined to

"a fashionable girls' school"- the Es-

ther Institute.76 Both of

these were united with the Starling Medical Col-

lege as the "university was mapped

out on a broad scale" that went "beyond

anything undertaken until that time in

the great West."77 Encouraged by

these developments, the synod expressed

its aspirations for the school as

follows:

The universities in connection with our

church in Germany possess

a world renown reputation, may we not

hope that our new institution

will gradually arise under the fostering

care of the church, and the

smiles of its great head, until it shall

ultimately compare in some re-

mote degree at least, with those

venerable institutions?78

The first classes met on September 12,

1850, in a temporary location

on East Town Street with fifty students

in attendance.79 Three years later

a new facility built in the

"Italian style" was dedicated. W. H. Seward,

then United States Senator from New York

and later to be Lincoln's Sec-

|

192 OHIO HISTORY

retary of State, delivered an address on the "Philosophy of Humanity."80 Located on a four acre lot on North High Street donated by Dr. Lincoln Goodale, the structure was extolled as "undoubtedly one of the handsomest of the various public buildings that adorn the city of Columbus."81 It was an edifice Fitted up in a style that makes it one of the most commodious build- ings of the kind in the country. The rooms for students are of good dimensions, and handsomely finished. Large Halls for the two Literary Societies give ample accomodations for those interesting auxiliaries of College education. The Chemical Laboratory is fitted up in a manner that will give every facility for chemical analysis, as well as experiments before class, and the Institution is supplied with the best Apparatus for study of Natural Philosophy.82 The school, begun with high hopes, quickly encountered difficulties in four different areas.83 First, there was the language problem. Instruction in the university was predominantly in the English tongue and most of the staff were native-born Americans, but the Ohio Synod's communicants were still largely German-speaking who believed they were being asked to support a school which slighted their native language. Second, there was the issue of the university's relationship to the church. Tension arose be- tween the president and his supporters: some envisioned Capital as a com- munity college; and others, the synod leaders, regarded the school as pri- marily a denominational institution. Third, because it was impossible to secure sufficient funds, there was disappointment engendered by the failure |

MATTHIAS LOY 193

to realize the ambitions of the founders

to make Capital an imitation of

a German university. Fourth, doctrinal

disagreements developed, dividing

the confessional, German speaking

members of the synod from the more

ecumenical, English language

communicants. Because of his inability to

solve these conflicts, Dr. William M.

Reynolds, the university's first presi-

dent, resigned in 1854.84

The following decade was a critical one

for the school. Though the uni-

versity was organized with a preparatory

academy, a college, and a seminary,

enrollment figures declined and the

institution's survival was in doubt. On

the eve of the Civil War there were only

ten pupils in the college and but

twenty in the academy.85 The

coming of war in 1861 further curtailed

growth, and in 1866 the college

graduated only three men, the seminary

eight.86 At this juncture,

Loy began his half-century career at Capital, re-

marking that in the 1860's "we had

neither a great University, nor great

men."87

Loy labored prodigiously at Capital,

occupying, at various times, the

positions of Professor of Mental and Moral

Science, President of the Sem-

inary, Dean of the Faculty, housefather

to the students, and, from 1881

until 1890, President of the University.

He taught nineteen hours a week,

offering such courses as Poimenics,

Dogmatics, Psychology, Logic, Dis-

course, Homiletical Exercises, and

Isagogics.88 As an educator, he was a

significant figure, influencing the

attitudes of hundreds of future Lutheran

ministers. In the opinion of historian

C. V. Sheatsley, "a new period in the

history of the institution began when

Loy entered upon his professional

duties," because:

M. Loy was a power in any position. He

... brought with him the

editorship of the Lutheran Standard

.... Since 1860 he had also been

President of the Joint Synod of Ohio.

And this office he also brought

with him to the school. We see ... how

in the Joint Synod the doc-

trinal and administrative leadership was

centered in the Seminary.89

Recognition of his role in uniting synod

and university was given by a

sister institution, Muhlenberg College,

when, in 1885, it conferred upon

him the honorary Doctor of Divinity

degree.90

One of the major events during Loy's

tenure at Capital was the reloca-

tion of the university from its North

High Street address, which it had oc-

cupied for more than twenty years, to a

ten acre campus on East Main

Street in Bexley. At the time of its

founding the campus had been outside

the city limits, but by 1876 Columbus

had encompassed the institution.

The move was felt desirable because the

north Columbus area was being

settled by "an uncouth folk... and

the increasing noise, dust, etc., and the

wear and tear which had rendered the

buildings quite unserviceable, again

impressed upon Synod the necessity of

looking for a new location."91 The

students, furthermore, were

"getting into fights with the 'Flytown' crowd,

a small settlement located just west of

the school. The settlement boys

did not approve wholeheartedly of the

'dudes' who were attending the

only university in Columbus at that

time."92

194 OHIO HISTORY

A site having been selected on the

National Pike just east of Alum

Creek, the students and faculty made the

"trek" of four and one-half miles

to Bexley on May 3, 1876, and on the

following June 20 the new campus

facilities were dedicated. In its Bexley

home the university, according to

one of its Catalogues, formed

"a pleasant little suburb of the city, present-

ing, however, all the advantages of a

quiet rural life."93

As an educator, Dr. Loy began his daily

schedule early in the morning.

After working several hours in his study

editing the Standard, he would

leave his home on East Rich Street for

school. For many years he walked

out East Main Street to the college, and

a former student recalled that,

Unless the weather was too stormy, he

made those several miles in

a measured tread, body erect, never

swaying from left to right. He might

have been a retired army officer. When

we met him coming or going --

no one told us young chaps to raise our

hats or caps. We saluted...

[and] he always accepted our gesture

with a smile and greeting.94

He arrived on campus promptly at 1:00

P.M., and the pupils remarked that

they could set their watches by his

appearance.95 When Loy first came to

"Old Cap," he found that

"the order and discipline of the school was far

from satisfactory" because

"there had been a lack of punctuality all around."

Professor Lehmann, the president, whose

duty it was to see that the classes

were properly scheduled, was often so

preoccupied with extra-curricular

activities, that he sometimes began his

lectures an hour or so late, and

"his hours were when he rang his

bell; that is about all that was certain."96

Loy's classes, in contrast, met on time,

and he insisted on prompt attendance.

Once in the classroom, he sat behind his

desk and lectured in a slow;

deliberate manner. He was "not

sprightly or active, but instead, quiet and

still," and he "did not pace

the floor, raise his voice, or use the blackboard,"

and while one student remarked that

"he never seemed to get excited," he

kept the pupils "on their

toes" by his habit of "oral quizzing."97 A

peculiarity

of the school was the necessity for the

professor to lecture on alternate days

in German and English, a procedure which

presented some difficulties for

scholars not familiar with the German

language. Dr. Loy helpfully employed

a simple vocabulary, spoke distinctly,

and made certain that each sentence

was understood. His excellence as an

instructor was described in 1901 by

a Columbus historian: "Dr. Loy is a

model teacher, respected and beloved

alike by his colleagues and his pupils;

a man of extensive learning, a profound

and clear thinker, and a good

disciplinarian."98

Because of Loy's preeminence in the

university, he was chosen as its

president on January 13, 1881, after the

death of W. F. Lehmann. Since

"the president's job had come to

include just about everything except

stoking the furnaces," this

respected teacher was not delighted with his

election. While he declined to accept

the office at this time, he recalled

that "manifestly the duties of the

Presidency must be performed, and I

continued to perform them as well as I

could." Dr. Loy finally did accept

the name as well as the responsibilities

of the position "for the sake of

order and appearance."99 During

his presidency the curriculum was centered

MATTHIAS LOY 195

around classical languages and religion,

and the "chief purpose" of the

institution was "to serve as a

feeder for the theological seminary." Enroll-

ment remained static throughout the Loy

decade; in the 1889-1890 school

year there were fifty-two boys in the

academy, seventy-one in the college,

and thirty-one in the seminary, for a

total of one hundred and fifty-four

pupils in the university.100

The social life of the campus was

representative of the pastimes of the

Gilded Age. At Christmas and on other

holidays the students got "cakes,

pies, and other things" from the

ladies' auxiliaries of various Columbus

Lutheran churches.101 Opportunities for

physical education were limited,

but "it was the Housefather's

responsibility to see that some exercise was

indulged in by all students."102

Chapel was an important aspect of college

activities, and worship was conducted

daily at 7:00 A.M. and 7:30 P.M. in

the winter months and at 6:30 A.M. and

8:00 P.M. in the summer season.103

College expenses were modest at Capital.

When Loy arrived in 1865, for

example, tuition was twenty dollars a

year for the grammar school, thirty

dollars for the college, and no charges

for the seminary. Board was $1.75

per week, paid in advance each month.

Advertisements stated that,

Room rent will be $6.00 a year, students

being requested to furnish

beds and bedding, tables, chairs, etc.

for their own rooms... [and]

coal can be had at about 15 cents per

bushel. Washing $1.00 per

month.104

While at Capital, along with his other

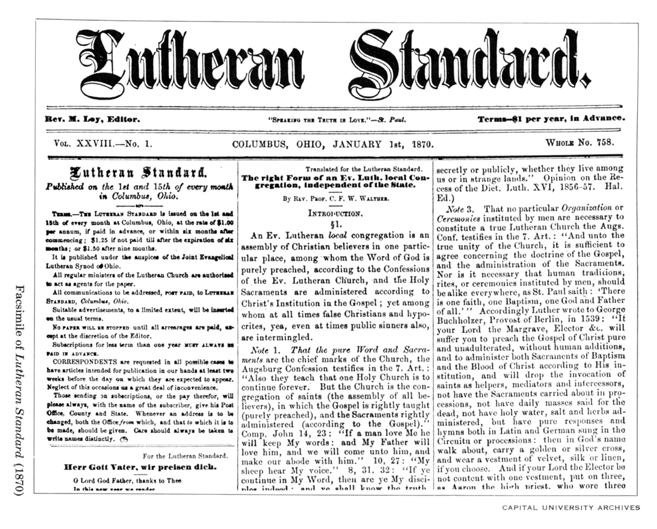

duties, Loy edited the Ohio Synod

journal, the Lutheran Standard. Founded

on May 25, 1842, by action of

the synod to "explain and defend

the doctrines of our Church" and to

"promote virtue and piety,"

the Standard had a perilous existence during

its first two decades and by April 1864

was faced with the threat of ex-

tinction.105 The paper had been

published wherever its editor resided, and

one historian commented that "the Standard

should have had a press

mounted on wheels."106 When Loy

assumed its editorship on April 15, 1864,

the periodical acquired a scholarly and

prolific columnist, a conscientious

publisher, and a permanent home.

He improved the format of the journal,

and by 1866 it appeared in quarto

form, containing eight pages, each with

four columns of print. The fre-

quency of publication was increased from

twice a month to weekly. Its con-

tent was enriched with vivid editorial

comment, religious news, doctrinal

essays, translations of German and Latin

theological works, and reprints

from other magazines, such as Godey's

Lady's Book. The production of

the paper, however, was a heavy task for

the editor, who received no salary.

After the copies of the Standard had

been printed, they were delivered to

Loy's residence for mailing. This meant

that his family had to "prepare

the wrappers, fold the papers, write the

addresses, get the paste ready,

put it on only where it belongs, and

whatsoever pertains to the mystery

of mailing without machinery."107

The children, who took a fancy to the

task, brought their playmates in to

assist them, and the boys from Capital

lent a helping hand. "Packing

night" became a party occasion, with pro-

|

fessor, family, and students working until after midnight when the stacked Standards were finally prepared for the drayman to deliver to the post office. When he took charge of the Standard, Loy discovered that there was "positively no money on hand." Early issues pleaded with subscribers to pay their overdue accounts, stating, "only feed the starving child and it will live." Lutherans were admonished to give the Standard to friends, and during the Civil War they were invited to send a pack to the troops.108 |

MATTHIAS LOY 197

Gradually the paper's debts were paid,

and by the dawn of the twentieth

century its circulation was 3,322, more

than a four-fold improvement over

the 700 subscribers in 1844.109

Related to his role as an editor was

Loy's contribution as a translator

and author. He rendered into English

numerous hymns and such works

as Hermann Fick's Life and Deeds of

Dr. Martin Luther, Johann Conrad

Diedrich's edition of Luther's Small

Catechism, and Luther's House Postil.

Loy wrote several original theological

studies, including The Doctrine of

Justification, The Essay on the

Ministerial Office, The Christian Church in

its Foundation, Essence, Appearance,

and Work, sermons on the gospels

and epistles of the traditional church

year, a commentary on the Sermon

on the Mount, an exposition of the

Augsburg Confession, and a treatment

of Christian prayer. As a poet, he

composed twenty hymns, two of which

are still used in the Service Book

and Hymnal of the Lutheran Church.110

Matthias Loy merits attention also as a

theologian. Along with Samuel

Simon Schmucker, Charles Porterfield

Krauth, and C. F. W. Walther, he

was one of the four most influential

Lutheran thinkers in the United States

in the nineteenth century. During Loy's

lifetime, the Lutherans of the

nation were divided doctrinally between

two antithetical positions -- "Ameri-

can Lutheranism" and "Old

Lutheranism." The first approach, identified

with Samuel Schmucker of Gettysburg

Seminary, advocated a recension

or revision of the Lutheran Confessions

so that they could be more readily

adjusted to both the American

environment and the temper of the Vic-

torian Era. Once this was done, it was

believed that the essential elements

of the Lutheran symbols would be seen to

be those convictions shared in

common by all Protestant Christians. The

Lutheran faith, furthermore,

would be vitally transformed by the

major forces found in American Chris-

tianity -- Puritanism, Pietism,

Rationalism, and Revivalism. This process,

it was felt, would make Lutheranism both

more evangelical and ecumen-

ical.111 The second approach, "Old

Lutheranism," was represented by C. F. W.

Walther of the Missouri Synod and Charles

Porterfield Krauth of the

General Council. They were persuaded

that the continued existence and

prosperity of the Lutheran Church in

North America depended upon a full

and faithful rediscovery of the

confessional statements of the sixteenth

century. The church, therefore, should

not conform to the intellectual

climate of the time, but should

transform the times by a return to the

"faith of the fathers." In the

confrontation between these two groups, Loy

early allied himself with the

Confessionalists. This was a result of the

impact of the personality of C. F. W.

Walther and his paper, Der Lutheraner.

As his theological system matured, Loy

became a Protestant or Biblical

Scholastic. His thought exhibited the

three formative elements found by

Theodore G. Tappert in seventeenth

century German Lutheran Ortho-

doxy -- an emphasis on biblical

authority, a concern for rigid methodology,

and an adherence to churchly

tradition.112 First, there was a passion for

the canonical Scriptures as a verbally inspired

revelation from God. Loy

was convinced that the Bible was

composed by men who served as secre-

198 OHIO HISTORY

taries for the Holy Spirit, and he

therefore rejected all forms of Higher

and Lower Criticism and admonished

Christians to:

Jealously guard their sacred treasures .

. . and concede nothing to

the criticism and the science that

arrogantly assert the supposed rights

of fallible human opinion against the

infallible divine authority.113

A second motif of his thought was his

effort to construct a comprehensive

theological system by the application of

Aristotelian logic to the study

of biblical passages. He hoped to arrive

at a grand synthesis of all of the

revealed truth in Scripture, and his

endeavors imitated "the solidity and

symmetry of the theological edifice

erected by our fathers in an age less

hurried and more thorough than the

present."114 A third feature was Loy's

traditionalism and his reliance upon the

accumulated experience of the Lu-

theran Church since the Reformation. He

accordingly attached great im-

portance to the writings of the

seventeenth century German Lutheran Scho-

lastics, Martin Chemnitz, Nicholas

Selnecker, John Gerhard, Abraham

Calovius, John Andrew Quenstedt, David

Hollaz and others. His familiarity

with the works of these orthodox

theologians served him well in his struggles

with the American Lutheran movement and

assisted him in his triumph

over it in the Ohio Synod.

Loy's theological contributions served

to preserve a distinctive Lutheran

Church in America and prevent its

absorption into a general American

Protestantism. He paved the way also for

the church's recovery of the doc-

trinal and devotional resources of the

Reformation. By focusing the atten-

tion of Lutheran immigrants on their

spiritual heritage, he helped them

to identify themselves in relationship

to the new nation.

The climax of Loy's career came in his

years as president of the Evan-

gelical Lutheran Joint Synod of Ohio

from 1860 until 1878, and from 1880

until 1894. In 1860, when Loy assumed

its leadership, the Ohio Synod was

only ten years older than its youthful

president. The synod had been

formed in 1818 by seventeen pastors who

served approximately seventy-

five congregations located between the

Appalachian Mountains of western

Pennsylvania and the plains of central

Ohio. Experiencing moderate and

steady growth, by 1854 it had included

ninety-three ministers who were

responsible for the care of two hundred

and thirty-four charges.115 It was

composed of four districts -- the

Western, Eastern, Northwestern, and a

non-geographical English District. The

membership was heavily German

and was concentrated in the upper Ohio

Valley.

Loy had three main problems as

president. First, from 1861 until 1865

he had to guide the Evangelical Lutheran

Joint Synod of Ohio through

the perplexities of the Civil War.

Second, from 1866 until 1878 he worked

to further the cause of Lutheran unity

in North America. Third, when the

merger schemes failed, from 1880 until

1894 he devoted his energies to the

expansion of the Ohio Synod into a

nationwide denomination.

Six months after Loy's election,

hostilities began between the North

and South at Fort Sumter in Charleston

Harbor.116 The Lutherans were

as divided in their response to the

ensuing conflict as were their fellow

MATTHIAS LOY 199

Americans. The General Synod of the

Lutheran Church in the United

States, the oldest and largest

association of Lutherans in the country, had

many southern communicants and was split

over the questions of secession

and slavery.117 The

Scandinavian synods of the upper Midwest were largely

Free Soil and Republican in sympathies.

In the lower Midwest there were

four predominantly German synods: Iowa,

Buffalo, Missouri, and Ohio.

On the whole, "the vast majority of

immigrant Germans of all classes op-

posed slavery and supported the

Union." The only exception of note was

Loy's close friend, C. F. W. Walther,

leader of the Missouri Synod, who

endorsed the Confederacy.118

Loy and his colleagues felt obliged to

offer a theological explanation of

the significance of the Civil War. The

prevailing sentiment among Ohio

Synod spokesmen was that the war was

spawned by iniquity and was sent

as a scourge of God to lead men to

repentance. Though the ordeal might

drive Christians to contrition for their

sins, it could just as readily cause

even greater demoralization. The duty of

the church, therefore, was to

preach the Gospel, comfort the

afflicted, conduct works of charity, and

pray for the return of peace. Ohio

Lutherans were urged to support the

federal government, not because it was

waging a "holy war," but because

of the injunctions in Matthew 21 and

Romans 13 for Christians to be

obedient to the state.119

The twelve years following the Civil War

were a period of reunion and

reconstruction for the nation. Like the

country, the Lutherans of America

found themselves still severely divided

by 1865. The land's largest Lu-

theran body, the General Synod, was rent

asunder by the secession of its

Scandinavian members in 1860, the

withdrawal of its southern communi-

cants in 1861-1863, and the exodus of

its conservative adherents in 1866.

The most pressing postwar problem for

the Lutherans was to plan some

kind of inter-synodical organization. In

this process the strong and undivided

Ohio Synod, under the guidance of Dr.

Loy, was to play a prominent part.

A first effort at Lutheran reunion began

on Tuesday, December 11, 1866,

when clergymen from thirteen synods

assembled at Trinity Church, Reading,

Pennsylvania. Loy was representing the

Ohio Synod and gave the opening

sermon of the convention.120 The

General Council of the Evangelical Lu-

theran Church of North America began to

take shape. It was hoped that

this agency would incorporate the

confessional Lutherans of the continent,

including the hitherto independent Ohio

Synod. Doctrinal disagreements

developed, however, which made it

impossible for Loy to sanction Ohio

participation in this plan of union.

This conviction, shared by his synod,

was that "Paramount to Love is

Faith, and more precious than Union is

the Truth."121

Unable to unite with the General Council,

the Ohio Synod was led by

Loy to look for more cooperation with

the powerful Missouri Synod of

C.F.W. Walther. Beginning in 1855 and

continuing until 1872, the Ohio

and Missouri Synods drew together.

Several factors favored this rapproche-

ment. Both bodies were predominantly German with memberships

con-

|

200 OHIO HISTORY

centrated in the Midwest. By the 1870's both were committed to a strict Lutheran confessionalism which suggested the possibility of sufficient doc- trinal concord to warrant a merger. After drafting a constitution in 1871, the Ohio, Missouri, Wisconsin, Norwegian, Minnesota, and Illinois Synods formed the "Evangelical Lutheran Synodical Conference of North America" in 1872, which was the largest union of Lutherans in the western hemisphere. For nine years the project prospered. Walther was feted in Columbus and was awarded an honorary doctorate by Capital University, and Loy was offered a position at the St. Louis seminary of the Missouri Synod.122 Doctrinal consensus and confraternity among Lutherans seemed accom- plished. Tensions, however, were developing. The Missouri Synod, superior in numbers and influence, began to dominate the Synodical Conference. Ohioans got the impression that the Missourians were asking, "We are the people, but who are you?"123 C. F. W. Walther, the undisputed master of the Missouri Synod, encountered misunderstanding and opposition among Ohio Synod ministers. Personality clashes occurred. Proposals were made |

|

to move Capital University and Seminary to St. Louis, arousing Ohio fears of total absorption. The tinder was ready when, in 1881, a doctrinal spark was struck which destroyed the conference. In that year theological war- fare broke out over the doctrine of Predestination. The Ohioans and Mis- sourians were shocked to learn that they did not actually share an identical faith, and in their mutual disaffection they commenced a polemical struggle that lasted into the early decades of the twentieth century. Dismayed at the collapse of his dreams of Lutheran unity, Loy centered his attention on the expansion of the Ohio Synod. This began in 1876 in what was possibly the first union of a northern and southern Lutheran church after the Civil War when the small Concordia Synod of Virginia was incorporated.124 Partly in response to its competition with the Mis- souri Synod, and partly in reply to the need to provide churches for the German immigrants, the Ohioans established new districts and congrega- tions in the upper Mississippi Valley. When Loy retired in 1894, the synod had ten large districts and congregations in more than half the states of |

MATTHIAS LOY 201

the Union. When he died in 1915, the

Ohio body had become international

with the addition of Canadian and

Australian districts. During the years

of Loy's leadership and later life, the

synod increased its membership seven-

fold, from 20,000 to 140,000

communicants, worshipping in more than 600

congregations. By 1918 it had a system

of parochial schools that employed

184 teachers and enrolled 9,827 pupils.

Its institutions of higher learning

included Capital University; a Normal

School in Woodville, Ohio; Luther

Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota; Hebron

Academy in Nebraska; Pacific

Seminary in Olympia, Washington; and

Luther Academy in Melville, Sas-

katchewan. Five hundred and two students

attended these schools. The

church expanded its ministry to those in

need, and in 1918 its homes for

orphans and the elderly numbered 174

residents.125 In the decades between

the Civil War and World War I, the Ohio

Synod took a gigantic step for-

ward and became a prosperous and powerful member of the

American family

of Protestant denominations.

The leader of Ohio's Lutherans, however,

started the new century with

severely impaired health. In May 1902

Dr. Loy suffered a critical attack

of angina pectoris and was

compelled to curtail his labors and to retire from

public life. His remaining thirteen

years were spent comfortably with his

immediate family in Columbus. On Tuesday

evening, January 26, 1915, he

passed away at the age of eighty-six

years, ten months, and nine days.126

Shortly before his expiration at 9:15

P.M. he had been working, in his cus-

tomary manner, on a manuscript, and when

he had written two pages, his

pencil, "with peculiar

appropriateness, stopped in the middle of an unfin-

ished sentence: 'When the Lord makes a

demand....'"127 A Columbus

newspaper reported that "his death

was as peaceful as the peace he had

enjoyed during ... years of retirement in

the quietude of his own home,

with all his family in close connection."128

Matthias Loy was the most prominent

pastor, educator, editor, author,

church president, preacher, and

theologian produced by the Evangelical Lu-

theran Joint Synod of Ohio and Other

States in its 112 year history. Nearly

every aspect of the synod's life was

affected and enriched by his labors;

and when he failed to establish a

confessional union of all of America's

Lutherans, he turned his attention to

increasing the size and effectiveness

of the Ohio Synod. A penetrating

theologian, Loy devoted his career to a

recovery of the Lutheran Confessions of

the sixteenth century and to the

creation of a doctrinally-conservative

Lutheranism in the United States.

Perhaps Loy's place in the Ohio story

was best summarized by the Rev-

erend Robert E. Golladay in a funeral

eulogy. He predicted that "when

men get the right historical

perspective, Dr. Loy will receive credit ... as

one of the greatest conservative leaders

of the Lutheran Church."129

THE AUTHOR: C. George Fry is As-

sistant Professor of History at Capital

University.