Ohio History Journal

RICHARD T. FARRELL

Internal-Improvement Projects in

Southwestern Ohio, 1815-1834

During the first three decades of the

nineteenth century, merchants, farmers, and

manufacturers successfully established

Cincinnati's economic prominence in the

West. Taking advantage of the city's strategic

location, pioneer merchants supplied

the increasing number of immigrants from

Europe and the eastern states with the

goods they needed before they moved up

the valleys of the Great Miami and

Little Miami rivers. As farmers

gradually settled this region, agricultural production

increased. Merchants began collecting

farm surpluses and providing farmers with the

merchandise they could not produce for

themselves. The availability of agricultural

surpluses helped to promote milling,

brewing, distilling, and packing industries,

and these in turn created new demands

for products from the fields and forests.

The resultant increase in farm

production encouraged manufacturers to produce

tools, machines, and other items for

households and farms. Together, the growth

of industries and expansion of

agriculture stimulated trade.1

The city prospered as a result of the

combined efforts of merchants, manufac-

turers, and farmers.2 Responding

to the demands for locally made goods, manu-

facturing interests played an

increasingly important role in the city's economy.

The value of products manufactured in

Cincinnati in 1819 was $1,059,459, and

1,238 of the city's total population of

over 9,000 were engaged in manufacturing

or related service industries. By 1830

the value of manufactured products had

reached $2,800,000, and more people were

involved in manufacturing than in com-

mercial or service occupations.

Commercial transactions followed a

similar pattern. In 1819 the city's exported

products, consisting chiefly of flour,

pork, bacon, hams, lard, whiskey and tobacco,

were valued at $1,334,080. By 1829 the

value and quantity of export items ex-

ceeded three million dollars.

Agricultural products still headed the list, but such

items as hats, cabinet furniture,

printing materials, clothing, casting machinery,

and tin and copperware appeared with

greater frequency. Taking into account

1. For general discussions of the

economic development of Cincinnati, see Richard C. Wade, The

Urban Frontier, the Rise of Western

Cities, 1790-1830 (Cambridge, 1959);

William F. Gephart, Trans-

portation and Industrial Development

in the Middle West (New York, 1909);

Randolph C. Downes,

"Trade in Frontier Ohio," Mississippi

Valley Historical Review, XVI (March 1930), 467-494.

2. The following evidence of economic

growth in Cincinnati is taken from Richard T. Farrell,

"Cincinnati, 1800-1830: Economic Development

Through Trade and Industry," Ohio History, LXXVII

(Autumn 1968), 111-129.

Mr. Farrell is assistant professor of

history at the University of Maryland.

|

price fluctuations and changes in transportation charges, it is still evident that the volume of goods imported into the city also increased during this period. In 1818 the value of imported goods was placed at $1,619,030. By 1830 imports were valued at $3,800,000. Salt, sugar, tea, dry-goods, and hardware dominated the list, but raw materials--iron (pig, bar, and sheet), lumber timber, raw cotton, and similar items which could be used in manufacturing and construction--appeared with greater frequency. Other statistics also suggest the degree of economic development occurring in the city. The urban population, for example, increased from 9,642 in 1820 to 24,831 in 1830. Transportation rates, both upstream and downstream, dropped substantially between 1815 and 1830 while land value increased. The city's com- mercial facilities were improved, and wholesalers and commission agents became more active in the economy. Cincinnati's business community encountered several problems in its rise to economic prominence, the most basic probably being transportation. Economic growth and rising standards of living as well as the political stability and cultural progress which generally accompany prosperity were all dependent upon improved transportation facilities. As a frontier agrarian community, the city needed contact with coastal trade centers for essential goods which were not available locally. With an isolated, debtor society anxious to make the city a major commercial- manufacturing center, it was imperative that new and improved trade routes be developed to export surpluses and reduce the unfavorable balance of trade with the |

6

OHIO HISTORY

East. Recognizing the crucial importance

of transportation to long-term economic

development, business and political

leaders knew that the city's future depended

upon the completion of an

internal-improvements program that would insure routes

to eastern and southern markets and

provide access routes to main transportation

arteries.3

Efforts by these leaders to complete

such a program provide a model study of

how the business community responded to

obstacles to economic development.

Internal-improvements advocates

approached the transportation problem with op-

timism, perseverance, and ingenuity, but

their plans were often frustrated by a

lack of funds and inadequate

governmental assistance. Through determination and

prudent use of the limited funds

contributed by the state and national governments,

however, they were able to construct a

transportation system which stimulated

immediate economic development and laid

the groundwork for future growth.

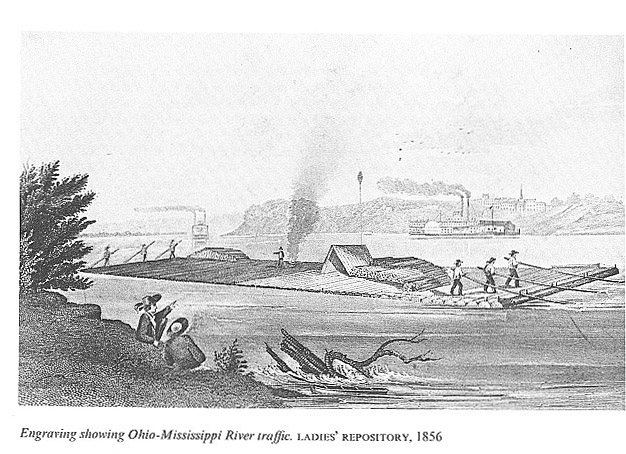

Between 1815 and 1834 all segments of

Cincinnati's economy depended on the

Ohio River.4 Most residents, therefore,

recognized the importance of removing

obstructions on this essential trade

artery so that the city could attain and secure

its position as the commercial and

industrial center of the Ohio Valley. Two proj-

ects designed to improve navigation on

the Ohio particularly interested the com-

mercial leaders of the city. These were,

one, the removal of obstacles along the

entire course of the river that made

navigation treacherous, and the other, the

construction of a canal around the Falls

at Louisville.

Popular river guides testify to the

dangers boatmen encountered in navigating

the Ohio. In addition to the more or

less anticipated obstacles--a shifting main

channel, sand bars, and ice--over which

man had little control, snags, sawyers,

rapids, and submerged rocks created the

greatest hazards.5 Men who knew the

river were convinced that many of these

obstacles could be removed easily and at

little expense. Encouraged by the

national government's interest in internal im-

provements during the first decade of

the nineteenth century, they urged Congress

to begin such a program. One editor

succinctly suggested that,

Western waters are OUR canals, and from

the simplicity of their wanted improvements,

are entitled to the first application of

moneys and subscription and appropriation from the

national government. How great would be

the folly to undertake other works, the labor

of years, however useful, and neglect

those of equal or tenfold more national importance,

which can be completed almost at any

moment in which they are undertaken.6

3. Harry N. Scheiber, Ohio Canal Era:

A Case Study of Government and the Economy, 1820-1861

(Athens, Ohio, 1969); Jacob H.

Hollander, The Cincinnati Southern Railway: A Study in Municipal

Activity (Baltimore, 1894), 10. For general discussions of

transportation problems in the Old North-

west, see Charles H. Ambler, A

History of Transportation in the Ohio Valley (Glendale, Calif., 1932);

R. Carlyle Buley, The Old Northwest:

Pioneer Period, 1815-1840 (Indianapolis, 1950), I, Chapter 7;

William T. Utter, The Frontier State,

1803-1825 (Carl Wittke, ed., The History of the State of Ohio,

II, Columbus, 1942), Chapters 4, 7; John

G. Clark, The Grain Trade in the Old Northwest (Urbana,

Ill., 1966), 1-7; George R. Taylor, The

Transportation Revolution, 1815-1860 (New York, 1951), Chap-

ters 2, 3, 4.

4. For a general history of

transportation in the Ohio Valley, see Ambler, Transportation in the

Ohio Valley.

5. Zadok Cramer, The Navigator,

Containing Directions for Navigating the Monongahela, Allegheny,

Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers . . . (Pittsburgh, 1821); Samuel Cumings, The Western

Pilot, Containing

Charts of the Ohio River and of the

Mississippi . . . (Cincinnati, 1829);

"Copy of Captain Chase's

Journal of Observations on the Manner in

Which the Contract with Mr. Bruce Has Been Executed

. . . Nov. 21 to Dec. 1825," in Senate

Executive Documents, 19 cong., 1 sess., No. 14; Buley, Old

Northwest, I, 432-435.

6. Liberty Hall and Cincinnati

Gazette (cited hereafter as Liberty

Hall), March 18, 1916.

|

Internal Improvement Projects 7 In 1817 commercial interests persuaded the state legislature to petition the Federal Government for funds to help finance river improvements. But Congress had not yet found a justification in the Constitution for Federal assistance, and it refused aid. Members of the Congress were deeply involved at this time in a constitu- tional debate over internal improvements that centered primarily on the division of powers between the state and Federal governments. The rights of corpora- tions and private citizens were apparently not involved. The presidential vetoes of internal-improvement bills in 1817 and 1822 and the congressional debates be- tween 1816 and 1824 suggest that the main issue was the right of Congress to ex- pand its powers beyond those specifically stated in the Constitution. Among the arguments for and against Federal assistance, the most significant were sectional interests, the factional split in the Republican party, and the fear that strengthening the powers of the government in one area would carry over into other areas.7 The congressional debate over this issue and the Panic of 1819 further delayed financial aid until May 1824. In that year Congress allocated funds to remove de- bris from the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Six months later, the chief engineer for the War Department signed a contract with John Bruce of Vanceburg, Kentucky, and work began on the Ohio River. Area residents were elated and confident that Bruce would succeed since he had devised a revolutionary "machine boat" which 7. Cincinnati Western Spy (cited hereafter as Western Spy), January 10, 1817; Carter A. Goodrich, Government Promotion of American Canals and Railroads, 1800-1890 (New York, 1960), 44; See also ibid., Chapter 2 for a discussion of constitutional debates; George Dangerfield, The Awakening of American Nationalism, 1815-1828 (New York, 1965), 18-21; Taylor, Transportation Revolution, 19; Ambler, Transportation in the Ohio Valley, 395. |

8

OHIO HISTORY

was said to operate so efficiently that

even the largest trees offered "but a trifling

resistance."8

The river improvement bill of 1824 was

of considerable importance to residents

of the Ohio Valley. It established a

precedent by which the national government

could participate in

internal-improvement projects of limited scope that were

planned by private or state enterprise.

During the next decade Congress received

numerous requests for additional

appropriations to clear the river, the majority of

which were approved. Moreover, the

national government soon increased its con-

tributions by subscribing to the stock

of private companies chartered by state gov-

ernments for specific improvements.9

Partly as a result of this change in policy,

residents along the Ohio River were able

to proceed more rapidly with internal

improvements.

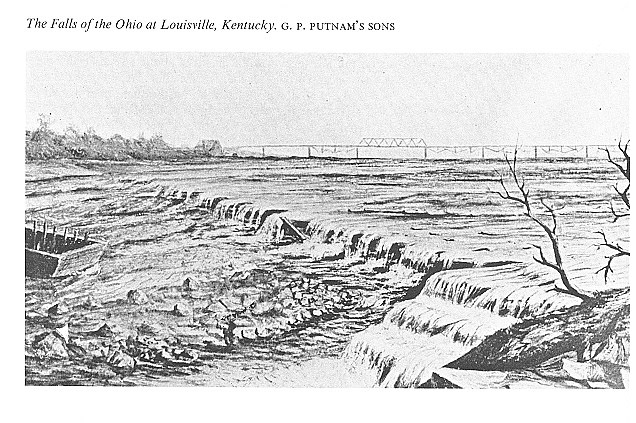

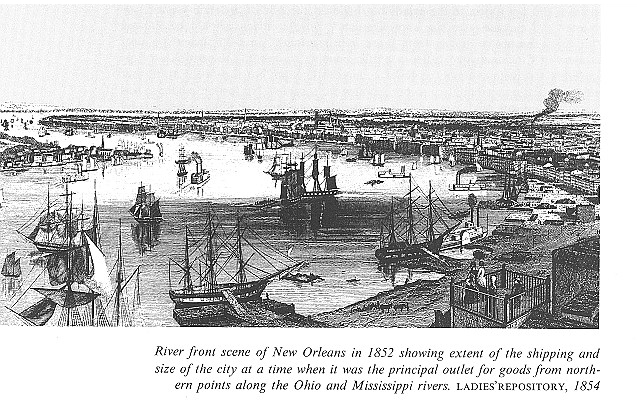

One project which benefited from the

government's new policy was the canal

around the Falls at Louisville. As

communities developed along the river, the Falls

became a matter of mounting concern.

Except for a few months each spring and

again in the autumn, this obstruction

usually created a natural barrier blocking

direct passage to New Orleans and forced

the transshipment of goods at Louisville.

Several proposals had been considered

between 1800 and 1815, but all proved too

expensive or impractical. Commercial

interests in Cincinnati believed that a canal

was the obvious solution, and they

attempted to obtain the assistance of other

communities along the river. Much to

their chagrin, however, towns below the

Falls (Louisville being the most

important) refused to cooperate. Because of its

strategic location, Louisville's economy

was largely dependent on the transshipment

business, and its merchants were

unwilling to risk the loss of their advantage. Other

communities below Louisville rejected

the suggestion at this time because the

Falls did not block their passage to New

Orleans.10

Civic leaders in the Queen City,

however, were persistent, dedicated, and pug-

nacious. Infuriated by Louisville's

chronic procrastination and especially by a report

that business interests on the Kentucky

side of the river favored a canal just wide

enough for keelboats, they accepted the

fact that a joint effort was impossible and

resolved to act independently of

Kentucky. Cincinnati businessmen then turned to

the Jefferson and Ohio Canal Company

which the Indiana legislature incorporated

in 1817 to construct a canal on the

Jeffersonville side of the river. Although the

directors of the company encouraged the

general assemblies of Ohio and Indiana

to contribute, they considered it

inadvisable in 1817 to depend too heavily on state

assistance. Instead they tried to

finance the venture through private investments

and a lottery. The Cincinnati directors

called frequent public meetings to arouse

interest and appointed two representatives

in each ward to solicit support, but all

their fund-raising efforts were of no

avail.11

8. Senate Executive Documents, 19

cong., 1 sess., No. 14. A more effective "snag boat" was designed

by Henry M. Shreve, superintendent of western river

improvements for the topographical engineers.

It went into operation in 1829 but was

used primarily for major projects and on other western rivers.

Louis C. Hunter, Steamboats on

Western Rivers: An Economic and Technological History (Cambridge,

1949), 193-200.

9. Goodrich, American Canals and

Railroads, 40; Hunter, Steamboats on Western Rivers, 190-191;

Ambler, Transportation in Ohio

Valley, 396.

10. Jacob Burnet, Notes on the Early

Settlement of the North-Western Territory (Cincinnati, 1847),

401-402; Louis C. Hunter, "Studies

in the Economic History of the Ohio Valley," Smith College Stu-

dies in History, XIX (October 1933-January 1934), 6-23.

11. Liberty Hall, January 20, May

26, 1817, January 5, February 11, 25, March 15, 18, May 20,

November 3, 1818; Western Spy, May

9, 23, 1817, January 3, May 9, 16, July 25, 1818, November 6,

1819; Cincinnati Inquisitor and

Advertiser (cited hereafter as Advertiser), October 13, July 7,

1818.

Internal Improvement Projects

9

Plagued from the beginning by financial

problems and construction difficulties,

the Jeffersonville and Ohio Canal

Company was soon doomed. Promoters in Cin-

cinnati began to lose interest in the

Indiana project by 1819, but not in a canal.

Realizing that private enterprise alone

could not succeed, they sought state assis-

tance.12 They were partially

motivated by recent discussions in the Ohio legislature

of plans to construct a canal from Lake

Erie to the Ohio River. If it allocated any

funds for internal improvements, they

reasoned, then preference ought to be given

to the canal at the Falls. A local

editor probably expressed the opinion of many

when he wrote that,

Whatever improvements may be meditated

for the benefit of commerce, either in clearing

out the beds of lesser streams, or in

connecting the Lakes with the waters of the Ohio, they

are all of much less importance to the

vital interests of the country, than a free and un-

interrupted passage to New Orleans.13

Several public-spirited citizens in the

Queen City suggested that the legislature

could not be expected to pay the entire

cost of constructing the canal. With con-

siderable justification, they pointed

out that it should be financed by all states

bordering the river. Since it would

benefit the country at large, the national gov-

ernment should also contribute.14 Aroused

by appeals from Cincinnati, merchants

and farmers on both sides of the Ohio

showed renewed interest in a joint project.

In 1819 the state assemblies of

Pennsylvania, Virginia, Kentucky, and Ohio ap-

pointed commissioners to study the

proposed sites and to recommend the one

offering the greatest advantages.

Indiana, however, did not participate in the pro-

ceedings because it was already

committed to the Jeffersonville project. Optimism

was so great in Indiana that the

legislature had agreed to subscribe two hundred

shares of the Jeffersonville Company's

stock and had set aside $10,000 from the

state's three percent fund for this

purpose.15 These actions seemed to mean that

Indiana would not participate in

competitive schemes.

Although the joint commissioners

completed their survey in 1820 and reported

favorably on the Louisville site, plans

to construct the canal did not materialize.

The states concerned then began

deliberations on their own improvement programs

and gave them first priority. Likewise,

the national government failed to provide

any tangible assistance. Indiana, whose

participation was desirable, if not essential,

not only boycotted the commission but

also continued to thwart the venture. At

the same time the commissioners' report

was made public, the Jeffersonville Com-

pany announced that its survey proved a

canal on the northern side of the river

would cost less than one on the southern

side. Finally, the Panic of 1819 prostrated

the West and delayed the completion of

all internal-improvement projects.16

Residents of Cincinnati were confused by

the conflicting reports of construction

costs at the two sites. They were also

disgruntled with the charters held by the

Kentucky and Indiana companies. In 1820

they asked the Ohio legislature to allo-

cate funds for a survey of both sides of

the river to determine whether a canal was

12. Liberty Hall, January 11, May

17, 1820.

13. Advertiser, February 16,

1819.

14. Cincinnati Directory for 1819 (Cincinnati,

1819), 71; Liberty Hall, April 25, 1819.

15. Ibid., May 27, 1820; Logan Esarey, "Internal Improvements

in Early Indiana," Indiana His-

torical Society Publications, V (1912), 67.

16. Liberty Hall, January 11,

April 4, July 5, 1820, January 3, 1824; John P. Foote, Memoirs of the

Life of Samuel E. Foote (Cincinnati, 1860), 170-173.

10

OHIO HISTORY

feasible and to resolve the question of

costs. Although funds were authorized for

the survey, Governor Jeremiah Morrow did

not employ an engineer until 1823. His

delay was apparently justified since

competent engineers were. scarce and those

who were qualified were working

elsewhere. Wasting no time, the legislature for-

warded the engineer's report to Congress

along with a request that the Federal

Government construct the canal. A House

committee recommended appropriating

$100,000 to help with construction

costs, but Congress refused to allocate the

money.17

Leading merchants in Louisville finally

succumbed to the inevitable. In 1825

they applied for a new charter for the

Louisville and Portland Canal Company.

Convinced that the company's intentions

were genuine, investors in Cincinnati

immediately subscribed nearly $200,000

in stock. But their enthusiasm was not

enough, and, as usual, actual

construction was delayed by financial problems. In

1826 and again in 1828 the national

government purchased stock. With this assis-

tance the company opened the canal to

traffic in December 1830. It was completed

the next year at a total cost of

$1,000,000. Of this amount the Federal Government

contributed $230,000.18

During the next decade the venture was a

success. The number of boats passing

through the canal rapidly increased, and

the company made money. By 1840 stock-

holders had received cash and stock

dividends amounting to ninety-nine percent

of their original investments. Moreover,

between 1831 and 1840 the canal satisfied

the immediate needs of farmers and

merchants above the Falls. Although its de-

fects soon became apparent, few

individuals complained. Gradually, however, mer-

chants and farmers who used the canal

regularly could no longer restrain their

irritation with the company. In their

opinion rates were excessive, and delays

caused by one-way traffic, low water,

and landslides and debris that blocked the

passage were inexcusable. In addition,

as the size of steamboats increased, the

utility of the canal was reduced. These

inconveniences, the result of poor construc-

tion and lack of planning, stimulated

demands for improvements. Again, Cincin-

nati residents led the campaign for

action, but results were slow in coming. Delayed

by legal, political, and financial

difficulties in addition to the Civil War, the enlarged

canal was not opened to traffic until

1872.19

Although the Ohio River was the city's

main trade artery, residents of Cincin-

nati did not devote all their efforts to

its improvement. Transportation routes to

the back country were also important to

the people of southwestern Ohio. Major

navigation projects would have a limited

effect on the economic development of

Cincinnati unless farmers could get

their products and purchases to and from the

city. Most businessmen, therefore, not

only supported such improvements but also

were determined that the projects should

terminate at the Queen City. Area resi-

dents investigated three separate

projects designed to facilitate the flow of agri-

cultural produce into the city:

developing navigation on the two Miami rivers,

building roads into the city, and

constructing a canal through the Miami Valley.

A few miles west of the city the Great

Miami River empties into the Ohio.

17. Liberty Hall, December 18,

1822, January 14, August 29, November 7, 1823, February 3, 1824;

Cincinnati National Republican and

Ohio Political Register (cited hereafter as National Republican),

May 27, 1823; House Reports, 18

cong., 1 sess., No. 98.

18. Liberty Hall, March 15, 1825;

Review of the Report of the Board of Engineers on the Improve-

ment of the Falls of the Ohio (Washington, 1834), 4.

19. House Miscellaneous Documents, 40

cong., 2 sess., No. 83; Hunter, Steamboats on Western

Rivers, 184-186.

|

Despite frequent disruptions by rapids, flatboats and other small boats could ascend the Ohio River for a distance of seventy-five miles from the mouth of the Great Miami. Farmers in the immediate vicinity of Cincinnati, nevertheless, did not ac- tively encourage improvements on this river. They apparently preferred spending money on roads which would provide a more direct route to the city. Likewise, merchants in Cincinnati showed little interest since farmers who used the Miami River route generally continued down the Ohio rather than coming upstream to the Cincinnati Market.20 The Little Miami River, emptying into the Ohio a few miles east of Cincinnati, was also a potential access route to markets. In 1816 farmers in Warren County initiated a project to improve navigation on the Little Miami, and they solicited support from Cincinnati and Hamilton County. Recognizing that traffic on the river would bypass the city, local merchants also opposed this project, but some farmers in the country offered assistance. Petitions were sent to the legislature in 1816 and again in 1817, but both times the General Assembly refused to act.21 Although the state government made numerous attempts to improve river naviga- tion between 1807 and 1830, no evidence was found indicating that Cincinnati residents actively encouraged these improvements. Without their help, local proj- ects had little chance to succeed since the city dominated the county both politi- cally and financially.22 This parochial attitude, apparently common among business and civic leaders, did not apply to road improvements. Roads throughout the West during the first 20. Gephart, Transportation and Industrial Development, 66. 21. Western Spy, May 3, 1816, July 4, 1817; Liberty Hall, June 30, 1817. 22. Wade, Urban Frontier, 336-338. For a discussion of improvements on state rivers, see Gephart, Transportation and Industrial Development, Chapters 4, 11. |

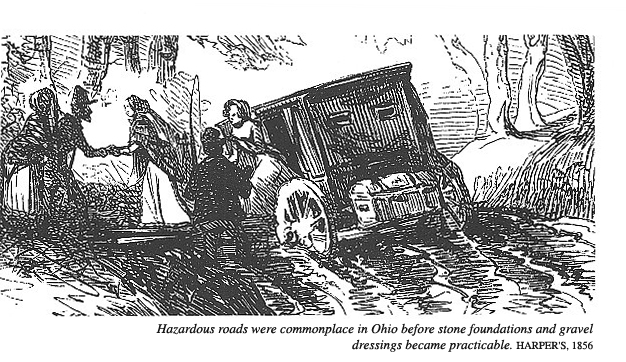

|

half of the nineteenth century were notoriously bad. Although not always by choice, most local roads were secondary in importance. They were chiefly built to connect with rivers which then became the main trade routes. Since Cincinnati was located between two navigable rivers, merchants considered road improvements essential. Radiating in a half circle from the city, roads were laid out to give farmers direct routes to Cincinnati markets. By 1816 six extended into the back country: the Co- lumbia road to the east, the Lebanon road to the northeast, the Dayton road to the north, the Hamilton and Lawrenceburg roads to the northwest, and the North Bend road to the west.23 As settlers advanced further into the Miami Valley, roads were extended and attempts were made to improve those already laid out. Following the War of 1812 turnpike companies increased in popularity, and many people were confident that at last a means of financing road construction had been found. But before actual improvements could be made, the Panic of 1819 disrupted the city's economy, forcing companies into bankruptcy. A typical example was a company chartered in 1817 to build a turnpike between Cincinnati and Dayton. Apparently the project was at first enthusiastically supported, but lack of capital and experience delayed construction until the company was ruined by the panic.24 Thus, even though con- struction was encouraged between 1816 and 1820, few roads were actually built. During the years immediately following the panic, interest in turnpike companies temporarily subsided. This can be partially explained by the absence of capital, but other factors were equally significant. In a letter to a constituent, Andrew Mack, a representative from Hamilton County, complained of the legislature's failure to 23. Buley, Old Northwest, I, 444-481; Utter, Frontier State, Chapter 8; Beverley W. Bond, Jr., The Civilization of the Old Northwest (New York, 1934), 364-386; Gephart, Transportation and Industrial Development, Chapters 3, 8; Samuel R. Brown, The Western Gazetteer, or Emigrant's Directory . . . (Auburn, N. Y., 1817), 280. 24. Acts Passed at the First Session of the Fifteenth General Assembly of the State of Ohio . . . (Columbus, 1817), XV, 84-92; Advertiser, September 14, 1819. |

Internal Improvement Projects

13

charter any new companies in

southwestern Ohio. In his opinion opposition came

from the back country which depended on

Cincinnati for a market. The farmers

in this region were opposed to turnpikes

because of tolls.25

But most people agreed that poor roads

impeded the development of the city

and should be improved. Since capital

was limited, numerous "do-it-yourself"

projects were considered. One of these

designed to improve the Mill Creek road

attracted attention. This road was the

main artery into the city from the north. All

of the city's newspapers urged the

public to attend a meeting called by local busi-

nessmen to discuss the project, and one

editor even went so far as to suggest that

individuals without "an

accommodating disposition" should stay at home. After a

lengthy debate those attending the

gathering decided to rebuild the road to meet

turnpike standards and then macadamize

it with rocks and crushed stone. All work

would be done by local residents, and a

board of managers would oversee con-

struction and determine the value of

work performed by other residents. Again

nothing practical was accomplished. A

few individuals opposed raising money for

materials by open subscriptions. They

argued that property owners along the route

should contribute more than other

citizens. When their suggestion was rejected,

they withdrew their support and the

project collapsed.26

There were numerous basic problems which

frustrated local efforts to build roads

prior to 1825; and although there is

abundant evidence to indicate general, en-

thusiastic support, few actual

improvements were made. Road-building advocates

had to depend almost exclusively on

local capital, and money was scarce. Further-

more, individuals were reluctant to

contribute money when they could not antici-

pate direct benefits. They wanted either

a dividend from their investment or a road

through or by their property. Dissension

between city and county residents, dis-

agreements over the priority of

projects, and lack of experience in construction

were also significant factors in

delaying local road building.27

Although financial assistance was

limited, the Federal Government tried to en-

courage road construction in Ohio. In

addition to appropriating funds for the Na-

tional Road, numerous post roads were

built in the state. Over these routes stage

lines ran between major towns, at least

during the summer and autumn, carrying

mail and passengers. In some cases mail

routes opened up outlying areas to stage

and wagon traffic, but generally mail

was still carried by horseback.28

The Federal Government also encouraged

road construction in other ways.

Probably the most significant was the

three percent fund. In Ohio's Enabling Act

Congress included a provision to return

to the state three percent of the net pro-

ceeds from the sale of public lands in

the state. The money was to be used ex-

clusively for surveying and constructing

roads. Although the fund undoubtedly

provided some valuable assistance, it

had several drawbacks. In the first place, the

amount received was not large. Including

supplementary contributions from the

state, total expenditures between 1804

and 1830 from the fund were only $342,-

814.15. Moreover, distribution of the

money was left to the discretion of the legis-

25. Andrew Mack to Isaac Bates, January

8, 1819, Box 1, Bates Papers, 1789-1873, Cincinnati His-

torical Society.

26. Advertiser, February 26,

March 19, 22, 29, April 5, 9, 19, May 17, 1823; National Republican,

March 18, 1823; Liberty Hall, March

14, April 4, July 22, 1823, January 23, 1824.

27. For examples of some of these

problems, see Liberty Hall, August 5, September 2, 12, Novem-

ber 28, December 5, 1823.

28. See Archer B. Hulbert, The

Cumberland Road (Cleveland, 1904), 77-78; Buley, Old Northwest,

I, 464-471.

14 OHIO HISTORY

lature. This proved to be an unfortunate

arrangement. It fostered political logrolling

and meant that much of the fund was

wasted on salaries for special commissioners

who were appointed each time a new road

was proposed. In addition, the arrange-

ment meant that small sums of money were

widely distributed over settled areas

of the state rather than concentrated on

a few major projects.29

Nevertheless, the three percent fund

provided some needed capital, and Cin-

cinnati was one of the first towns to

benefit. In 1804 the legislature appropriated

part of the Federal money for the

construction of two roads into the settlement.

Other appropriations were made from time

to time for road surveys, bridge con-

struction, and improvements on existing

roads. Through this fund the state's road

system advanced much more rapidly than

it would have if left to its own resources.30

The state government was not as generous

in appropriating its own money for

road improvements as it was with the

three percent fund. In general, it encouraged

projects between 1815 and 1834 but left

the financing to local enterprise. In 1817

Governor Thomas Worthington tried to

persuade the legislature to assume the

responsibility for building north-south

and east-west through roads, but he was un-

successful. Some money was added to the

three percent fund, but by this time it

was also used for bridge construction

and improvements on existing roads. The

legislature, however, facilitated actual

construction of new roads by granting liberal

charters to turnpike companies,

establishing construction standards, requiring able-

bodied males to work on the roads, and

levying a special state tax that was re-

turned to the counties for construction

purposes.31

The charters granted to turnpike

companies illustrate in part the willingness of

the legislature to encourage road

construction. In 1828 civic leaders from south-

western Ohio obtained charters for the

Cincinnati, Lebanon, and Springfield Turn-

pike Company with an authorized capital

of $150,000, and the Cincinnati,

Columbus, and Wooster Turnpike Company

with an authorized capital of $200,000.

Following a standard practice, both

charters established routes, set construction

specifications and toll rates, divided

managerial responsibilities among stockholders

in towns concerned, and included

provisions by which the legislature could pur-

chase the company. Although later

charters granted more liberal terms, these com-

panies also received some concessions

from the legislature. They were given the

right of eminent domain, exclusive

rights to construct roads over described routes,

and permission to sell stock to the

county commissioners. Companies such as these

were only a beginning. Within ten years

the legislature had chartered eight turn-

pike companies, some of which were to

build roads in southwestern Ohio.32

Appeals urging support for road companies

were eloquent and optimistic. In a

speech pointing out advantages of

improved roads, the engineer for the Cincinnati,

Columbus, and Wooster Company exhorted:

Are you a philanthropist, and delight in

the improvement of your race? Improve, then,

your roads. Are you humane and take

pleasure in seeing the condition of your faithful

animals ameliorated? Improve your roads.

Are you religious, and aim to attend the house

29. Gephart, Transportation and

Industrial Development, 131-134.

30. Acts Passed at the Second Session

of the First General Assembly of the State of Ohio . . . (Chil-

licothe, 1803), I, 136-145; Gephart, Transportation

and Industrial Development, 134.

31. For a discussion of turnpike

charters and road building, see ibid., Chapter 8.

32. Cincinnati, Lebanon, and Springfield

Turnpike Company Charter; Cincinnati, Columbus, and

Wooster Turnpike Company Charter, Ohio

Turnpikes and Canals [n. d.]; miscellaneous pamphlets and

documents on internal improvements

collected by the Cincinnati Historical Society Library; William D.

Gallagher, "Ohio in 1838," The

Hesperian, I (May 1838), 8.

Internal Improvement Projects

15

of God in time, and with your passions

unruffled? Improve your roads. Do you belong to

a civilized community in any capacity,

and wish to increase and extend the blessing of

civilization? The same answer applies

with equal force.33

Similarly, but with less verbosity,

newspaper editors encouraged their readers to

support the companies. Their appeals

brought results and construction began, but

the roads were not completed for several

decades.34

Lending impetus to the demands for new

roads after 1825 was the state's deter-

mination to construct a canal system.

The two main branches of the system, the

Ohio Canal and the Miami Canal, were not

completed until 1834, but sections of

both were opened to traffic beginning in

1827. As new sections were completed,

local residents rushed to build access

routes to the artificial waterways. Rarely

could these be classified as improved

roads, but they were essential and improve-

ments came with time.35

The construction of the canal system

connecting Lake Erie with the Ohio River

was by far the most ambitious and

significant internal-improvement project under-

taken by the state between 1815 and

1834. Such a canal had been suggested early

in the state's history, but in the

absence of traffic and capital the project was not

seriously considered until after the War

of 1812. During the next decade business

and political leaders repeatedly urged

the General Assembly to appropriate funds.

In their opinion a canal would not only

provide an outlet for the interior regions

of the state but also would facilitate

the flow of trade between the East and West.36

Opposition to the plan in different

sections of the state was difficult to overcome.

Some individuals opposed it because

their area of the state would not benefit, and

others favored the more traditional road

and river improvements. Some feared the

state would incur too large a public

debt, and still others opposed an increase in

taxes. Governor Ethan A. Brown observed

in 1821 that,

The magnitude and novelty of the

enterprise and the dread of incurring a debt of so con-

siderable [an] amount as might be

required to complete the work, was sufficient to deter

many; but some local opposition, and

particularly no surplus of money . . . induced the

friends of the measure not to press the

step of authorizing a survey and estimates this year.37

Agitation for a canal system brought

results in February 1825. At that time the

legislature authorized the construction

of the two main lines of the system. The

most ambitious of these was the Ohio and

Erie Canal. It was to run from Ports-

mouth on the Ohio River to Cleveland on

Lake Erie using stretches of the Scioto,

Licking, Muskingum, and Cuyahoga rivers.

The second part of the system was

the Miami Canal from Cincinnati to

Dayton through the Great Miami River Val-

ley. These routes were selected to gain

the support of the most heavily populated

area of the state and were not, because

of terrain features and an inadequate water

supply, the most desirable. In 1822 the

canal commissioners had authorized surveys

33. John S. Williams, Address to an

Enterprising Public upon the Improvement of Roads, and the

Introduction of Track Roads (Cincinnati, 1833), 4-5.

34. Charles Cist, Cincinnati in 1841:

Its Early Annals and Future Prospects (Cincinnati, 1841), 80-82.

35. Buley, Old Northwest, I, 450.

36. Chester E. Finn, "The Ohio

Canals: Public Enterprise on the Frontier," Ohio State Archaeo-

logical and Historical Quarterly, LI (January 1942), 38-39.

37. Ethan A. Brown to Jonathan Dayton,

February 4, 1821, Brown Papers, Ohio Historical Society.

See also P. Beecher to [?], January 15, 1825,

Beecher-Trimble Collection, 1817-1892, Cincinnati His-

torical Society Library; [C. C.

Huntington and C. P. McClelland], History of the Ohio Canals: Their

Construction, Cost, Use, and Partial

Abandonment (Columbus, 1905), 7-14.

16

OHIO HISTORY

for five different river systems: the

Mahoning and Grand route; the Cuyahoga,

Tuscarawas, and Muskingum route; the

Black, Killbuck, and Muskingum route;

the Scioto and Sandusky route; and the

Maumee and Great Miami route. Engi-

neers considered each of these

alternatives practical, but as frequently happened,

practical considerations were ignored

for political expediency.38

Canal advocates not only sacrificed the

most desirable routes but also agreed

to other sectional demands to win votes.

The same act allocated funds for road

improvements in the northwestern part of

the state and included a promise from

the legislature to consider at a later

date the question of extending the Miami

Canal to Lake Erie. To placate other

areas of the state, the assemblymen agreed

to support legislation requiring all

counties to levy a tax for public education and

to revise the state's system of

taxation.39

Letters and editorials in Cincinnati

newspapers suggest that at first some

internal-improvement advocates in the

Queen City only reluctantly supported the

state's canal project. With some

justification they feared it would divert capital

needed to construct the canal at the

Falls on the Ohio River. In their opinion the

state should ask the national government

for assistance in building the canal from

Lake Erie to the Ohio River. If Congress

agreed, local and state funds could be

used for other projects.40

In 1820 the legislature approved a

resolution requesting the state's congressional

representatives to obtain a Federal land

grant for this trans-state canal. Congress,

however, was not inclined to make such a

concession at this time. The next year

the Ohio delegation asked Congress to

authorize a survey for an Ohio-Erie canal,

but again met refusal. Further attempts

to obtain Federal assistance were tempo-

rarily abandoned, and advocates of the

project accepted the fact that the state

would have to assume the initiative.41

Some local opponents of the proposed

canal argued that it would reduce the

commercial importance of Cincinnati if

the canal terminated west of the city. A

few business leaders believed that once

completed, farmers would use the canal

to by-pass the city and continue down

the river. Or, worse yet, merchants and

wholesalers could go to the farmer,

purchase produce, and ship it directly to New

Orleans. At the same time, farmers

living near Cincinnati contended it would bring

more produce to the city and lower

prices. To the editor of the Liberty Hall, these

fears were not justified:

Nay, we assume it as a position not to

be disputed, that the canal will increase the com-

merce of the city; that the produce of

the country will increase, that a wider and more

extensive scope of country will be made

tributary to the city; and that, so far from being

a detriment, the canal will make

Cincinnati more flourishing than it was ever known to be

before.42

When it became apparent that the state

government was actually going ahead

38. Huntington and McClelland, Ohio

Canals, 15-19.

39. Caleb Atwater, A History of the

State of Ohio, Natural and Civil (Cincinnati. 1838), 262; Hunt-

ington and McClelland, Ohio Canals, 16-18;

Buley, Old Northwest, I, 493-494; Francis P. Wisenburger,

The Passing of the Frontier,

1825-1850 (Carl Wittke, ed., The

History of the State of Ohio, III, Columbus,

1941), 92-94.

40. Advertiser, February 16,

September 28, 1819; Liberty Hall, March 16, 1819, February 22, 1820.

41. John Kilbourn, comp., Public

Documents Concerning the Ohio Canals . . . from Their Com-

mencement down to the Close of the

Legislature of 1831-1832 (Columbus,

1832), 12, 15; Liberty Hall,

January 24, 1821.

42. Ibid., March 1, 8, September

20, 1825.

Internal Improvement Projects

17

with its plans, another group of

Cincinnati residents voiced its disapproval. These

persons did not object to the canals but

believed the role of the state was only to

"foster and encourage public

improvements"; private citizens should be allowed

"to enjoy the profits arising from

those improvements." In 1822 several political

leaders in Cincinnati had called a

public meeting to discuss the possiblity of or-

ganizing a private company to build a

canal to Dayton, but they went no further

than appointing a committee to raise

money for a survey. No further evidence was

found to indicate that local residents

seriously considered building the canals by

chartered companies.43

The lack of interest in any private

undertaking can be explained, perhaps, by

the opposition of the state's canal

commissioners. They argued that chartered com-

panies were monopolies which had been

granted "intangible and irrevocable" privi-

leges, and experience had demonstrated

that they frequently disregarded the

public's interest for the sake of

profits. Therefore, the commissioners concluded,

"It would be extremely hazardous

and unwise, to entrust private companies with

making those canals, which can be made

by the state."44

At the state level Governor Ethan A.

Brown, frequently called the "Father of

Ohio Canals," and Micajah Williams,

a state representative from Hamilton County

and later a canal commissioner, were

dynamic and tireless leaders in the campaign

for a canal system. In Cincinnati such

men as Jacob Burnet, Peyton S. Symmes,

Nathan Guilford, Daniel Drake, Ethan

Stone, and Samuel W. Davies endorsed the

plan and worked diligently persuading

others that a canal system would bring

numerous advantages to the city and

state. Moreover, public antagonism dimin-

ished after the legislature agreed to

finance the surveys for a canal at the Falls.

With the assurance of state aid for the

city's project, residents of the Queen City

began to take active interest in the

state canal system.45

Between 1820 and 1825 Cincinnati editors

printed numerous articles and edi-

torials pointing out the economic and

political importance of canals. At first some

of them attempted to use the Ohio-Erie

project to coerce Louisville and other river

towns into building a canal at the

Falls. The editor of the Liberty Hall hinted that

the Ohio River was not the city's only

route to the East, and that if Louisville con-

tinued to procrastinate, an alternative

would be built. Besides, he continued, with

two outlets,

The farmer's hopes would be doubled, and

a large part of the western population, instead

of looking only to the forlorn hope of a

damp, sickly town [New Orleans], remote from

the ocean and from Europe, with little

solid capital, where produce is often spoiled before

it arrives, or devoured by charges

before it is sold, would have access to the surest and

best supplied market in America.46

Other writers pointed out that the

canals would provide employment, put money

into circulation, and help the state's

economy recover from the Panic of 1819. Using

as examples similar projects in other

states, notably New York, they demonstrated

how canals increased land values and

created water supplies that could be used

43. Advertiser, June 11, 1822,

December 22, 1824, February 5, 1825; Western Spy, June 8, 15, 1822.

44. Third Annual Canal Commissioners'

Report, January 8, 1825, in Kilbourn, Public Documents,

138-139.

45. Liberty Hall, February 18,

December 6, 1820, June 12, 1822; Advertiser, January 11, February

15, 1820.

46. Liberty Hall, November 18,

1820.

|

to supply power for manufacturing. To those who wanted road improvements, they hinted that toll revenues would produce a surplus in the treasury for road construc- tion. With typical western optimism, they failed to question the economic sound- ness of the project. To them, there was little doubt that canals brought "happiness and prosperity, wealth and population."47 After the Ohio legislature approved the act of 1825, most residents in Cincinnati apparently focused their attention almost exclusively on the Miami Canal. Beyond periodic progress reports, the city's newspapers printed few references to the main branch of the system. Developments in the Miami Valley were of much greater interest to their subscribers. Ground-breaking ceremonies were held on July 21, 1825, with all the pageantry common to western celebrations. But the festivities were quickly concluded. "The next morning five teams and a large number of hands were at work on the very spot where the first earth was removed." Four months later, 750 men and 360 teams were working on different sections of the canal, and more laborers were "flocking in" every day. Many of these were farmers who lived near the construction sites; others were workers from the East Coast and newly arrived immigrants, particularly the Irish.48 47. Ibid., February 6, 1822, August 27, September 3, October 12, 1824, January 7, 1825; National Republican, September 14, 1824. 48. Liberty Hall, July 26, 1825; National Republican, December 6, 1825; Weisenburger, Passing of the Frontier, 95-96. |

Internal Improvement Projects

19

In addition to the usual financial

difficulties and problems created by lack of

experience in construction techniques,

irresponsible contractors caused further de-

lays. The state commissioners let

contracts for specified jobs to the lowest bidder.

Unfortunately, too many individuals

suddenly considered themselves canal engi-

neers, and they submitted bids without

accurately estimating costs. Then, when

they realized they could not make a

profit, they abandoned the job.49 Even though

other problems continued to delay

construction, on November 28, 1827,

three fine boats, crowded with citizens,

delighted with the novelty and interest of the occa-

sion, left the basin six miles north of

Cincinnati, and proceeded to Middletown with the

most perfect success. The progress of

the boats was equal to about three miles an hour,

through the course of the whole line,

including the detention at the locks and all other

causes of delay, which are numerous in a

first attempt to navigate a new canal, when masters,

hands and horses are inexperienced, and

often the canal itself in imperfect order. The boats

returned to the basin with equal

success, and it is understood they have made several trips

since, carrying passengers and

freight.50

With the exception of the connecting

locks, the entire length of the Miami Canal

(sixty-seven miles) from Dayton to

Cincinnati was completed by January 1829 at

a reported cost of $746,852.70. The

question of a southern terminus had long cre-

ated dissension. Area farmers preferred

the cheaper route, following the course of

the Miami River. But this meant the city

would be by-passed, and local merchants

had no intention of letting this happen.

The merchants won their point, and the

canal was temporarily terminated less

than a mile from the river. Once the deci-

sion was made some business leaders

petitioned the legislature to make this the

permanent terminal point. Although they

were unsuccessful, they blocked further

construction until 1832, and the

connecting locks were not completed until 1834.51

The legislature discussed the

possibility of extending the Miami Canal to Lake

Erie at the same time it passed the

original act. It did not, however, authorize the

extension until 1831. At first Ohio

residents were reluctant to support the northern

extension. Canal advocates in Indiana

were as anxious as their counterparts in

Ohio to complete a transportation link

between the Ohio Valley and Lake Erie.

Early in the 1820's they formulated

plans to construct the Wabash Erie Canal via

the Wabash and Maumee rivers to Lake

Erie. To help cover construction costs,

Congress in 1827 gave the state of

Indiana a land grant amounting to all lands

along the entire route of the canal, on

an alternate section pattern ten miles wide.

This meant, in effect, that Indiana was

given jurisdiction over some of Ohio terri-

tory since the Maumee cut through the

northwestern section of the state. Ohioans

were not pleased with this development.

The conflict, however, was resolved through

legislative negotiations. Ohio agreed to

construct that part of the Wabash-Erie

Canal which lay within its borders and

Indiana gave up its claim to the land in

49. Micajah Williams to Alfred Kelly,

April 12, 1826, in "Letters to Ohio Canal Commissioners,"

Cincinnati Historical Society Library. See

also Huntington and McClelland, Ohio Canals, 22-29;

Weisenburger, Passing of the

Frontier, 94-97.

50. Sixth Annual Canal Commissioners'

Report, January 17, 1828, in Kilbourn, Public Documents,

284.

51. See Kilbourn. Public

Documents: Seventh Annual Canal Commissioners' Report, January 6,

1829, 333-334; Fourth Annual Canal

Commissioners' Report, December 10, 1825, 187-188; Special

Report of Canal Commissioners, February

16, 1830, 389-390; Tenth Annual Canal Commissioners'

Report, January 11, 1832, 2-5;

Cincinnati Saturday Evening Chronicle (cited hereafter as Chronicle),

January 31, 1829; Liberty Hall, July

29, August 5, 1829.

20

OHIO HISTORY

Ohio that Congress had included in the

1827 grant. Thereupon, Ohio residents

showed renewed interest in completing

the Miami extension.52

Actual construction on the northern

extension of the Miami Canal did not begin

until 1837. By 1845 the 114 mile canal

from Dayton to Toledo was completed.

Indiana began work on the Wabash and

Erie Canal several years earlier (1832).

By 1842 the junction with the Miami

Extension was completed, and a year later

the Wabash Canal was opened from Lake

Erie to Lafayette, Indiana. Although

the Miami Extension had almost no effect

on Cincinnati during the period of this

study, it was significant because it was

financed in part by a land grant from the

national government. This marked a

precedent whereby Congress could increase

its involvement in internal

improvements.53

As soon as the Miami Canal was opened to

traffic, newspaper editors assured

the public that the project was a

success. They pointed out that it had reduced

freight rates and increased the volume

of produce brought to the city not only

from the immediate vicinity but also

from the whole Miami Valley. As an example

one editor pointed out that in one week

in March 1829, more than 575 tons of

produce had been brought to the city.

The cost of transporting the whole amount

for a distance not exceeding twenty-five

miles was $2,800, and it only took ten

boats, sixty horses, sixty men, and

thirty boys three days to do the job. By com-

parison, to bring a similar amount by

wagon the same distance, it would take 575

wagons, 2,340 horses, and 575 men. And

then the cost would have been $7,200.

Moreover, toll receipts indicated the

canal would pay for itself in a short time.54

Such optimism was only partially

justified. Transportation costs declined, and

the volume of produce brought to

Cincinnati increased. Toll receipts, however, re-

mained disappointingly low. In 1828 the

state's entire canal system collected only

$8,570.69 in tolls. By 1832 the amount

had increased to $50,974.73, but this was

not enough to pay the interest on the

debt the state had incurred in constructing

canals. Although toll receipts continued

to increase between 1832 and 1840, they

did not reach the totals that advocates

of the program had promised. This can be

explained in part by the fact that

traffic remained primarily local.55

By 1835 neither the Miami nor the other

Ohio canals had made any significant

impact on the flow of exports from the

area served by Cincinnati. The city still

depended almost exclusively on the Ohio

River for sending flour, pork, whiskey,

corn, and tobacco--the main exports of

the region--to the New Orleans market.

Likewise, imports received in the city

continued to follow established trade routes.

Salt and sugar were brought up the river

from New Orleans. Iron came down the

river from Pittsburgh. Manufactured

items, depending on their weight, came from

both the eastern and southern routes.

One authority concluded that:

In short, the northern part of the Old

Northwest and the southern part each had its own

commercial outlet or gateway. In fact,

the southern part had two, the eastern and southern.

While the two parts of the Old Northwest

were now connected by a canal that ran from

52. Scheiber, Ohio Canal Era, 99.

53. For a discussion of the extension of

the Miami Canal and the means by which it was financed,

see Huntington

and McClelland, Ohio Canals, 34-38; Burnet, Notes, 455-460.

Burnet was largely re-

sponsible for getting the bill

authorizing the grant through Congress. Documentary evidence of at-

tempts to obtain Federal assistance can

be found in Kilbourn, Public Documents.

54. Chronicle, March 21, 1829. See

also National Republican, April 4, May 6, 1827; Chronicle,

March 22, 1829.

55. Cist. Cincinnati in 1841, 84;

Eleventh Annual Canal Commissioners Report, January 22, 1833,

in Kilbourn, Public Documents, 37;

Huntington and McClelland, Ohio Canals, 43, 78.

Internal Improvement Projects

21

the Ohio river to Lake Erie, neither

part was making any considerable use of the outlet

of the other part.56

Although railroads belong to a later

era, some internal improvements advocates

claimed that they were superior to other

forms of transportation even before the

state's canal system was developed

enough to meet the expectations of its support-

ers. No one went so far as to suggest

that railroads should replace the canals al-

ready under construction. Rather, they

wanted them to supplement the system and

provide new routes to the coastal

cities, bypassing the river route through New

Orleans. Speaking for some railroad

promoters who were in the city, one writer

maintained that,

We are heartily tired of a Louisiana

Monopoly; it cannot be possible that the immense

productions of the almost boundless

regions of the West, are to be doomed always to be

filtered through the commission houses

of Orleans, or subject to the precarious market of

that city.57

One of the first proposals for a

railroad connecting Cincinnati with the East

Coast was made in the fall of 1827. At

this time a few prominent citizens discussed

the possibility of building a line from

Cincinnati to Charleston, South Carolina,

but they took no action.58 Eight

years later, in 1835, railroad advocates revived

the plan and formed a committee to

promote the project. Although it was to be a

cooperative venture among several

states, Daniel Drake, William Henry Harrison,

James Hall, and Edward D. Mansfield from

Cincinnati played important roles in

the proceedings. In its entirety the

project was quite comprehensive:

The proposed main trunk, from Cincinnati

to Charleston, would resemble an immense

horizontal tree extending its roots

through, or into, ten states, and a vast expanse of unin-

habited territory, in the northern

interior of the Union, while its branches would wind

through half as many populous states of

the southern sea-board.59

The Kentucky legislature chartered a

company in 1837 to build this railroad,

but the Panic of 1837 forced plans to be

temporarily abandoned.60

The Ohio legislature chartered the first

railroad company in the state, the Ohio

Canal and Steubenville Railway Company,

in February 1830. This company, with

a capital stock of $500,000 was to

construct a single or double lane track from

Steubenville to the Ohio Canal. Other

companies soon followed. The next year

the legislature chartered the Richmond,

Eaton, and Miami Railroad Company to

build a line from Richmond, Indiana, to

the Miami Canal. In 1832 it chartered

the Mad River and Lake Erie Railroad

Company to build an alternative route to

the Miami Canal Extension. Two other

companies, the Franklin, Springborough,

56. A. L. Kohlmeier, The Old

Northwest as the Keystone of the Arch of American Federal Union:

A Study in Commerce and Politics (Bloomington, Ind., 1938), 19-21; see also

Gephart, Transportation

and Industrial Development, 118-119. In a more recent study, Clark suggests that

"this division of Ohio

into two more or less separate market

structures is of little importance before 1835, . . ." He points

out that most traffic from the state

moved south before 1835 and that railroads significantly altered

trade patterns during the 1850's. Clark,

Grain Trade in the Old Northwest, 19.

57. Chronicle, March 17, 1827. See

also ibid., February 20, 1830, January 1, 22, February 12, 1831,

February 18, 1832; Cincinnati

American, May 27, 1831.

58. Ebenezer S. Thomas, Reminiscences

of the Last Sixty-Five Years ... (Hartford, 1840), I, 104-111.

59. Rail-Road from the Banks of the

Ohio River to the Tide Waters of the Carolinas and Georgia

(Cincinnati, 1835), 7.

60. Hollander, Cincinnati Southern

Railway, 10-11.

22 OHIO

HISTORY

and Wilmington Railroad Company and the

Chillicothe and Lebanon Railroad

Company, were chartered the same year to

build feeder lines to the Miami Canal.

The Cincinnati, Harrison, and

Indianapolis Railroad Company and the Cincinnati

and St. Louis Railroad Company, also

chartered in 1832, planned to build lines

that would open new territories to trade

with Cincinnati.61 This was only a beginning,

for during the next decade the

legislature chartered many additional companies.

All of these charters contained similar

provisions. Capital stock varied from

$500,000 to $1,000,000 depending upon

the size of the project. Likewise, the num-

ber of directors varied, nine or twelve

being the most common. The directors had

the right to select the "best

route" between the specified cities, and most charters

provided for the right of eminent

domain. A few included a provision authorizing

the use of construction materials along

the route. In all cases the state retained

the right to purchase the company.

Although several leading citizens tried to stim-

ulate interest in railroad construction,

none were actually built in the Cincinnati

region before 1834.

By expanding the city's trade area, most

of these developments contributed

significantly to the economic growth of

Cincinnati. But other factors were also in-

volved. Perhaps the most significant was

the rapid decline in transportation costs.

Statistical information on

transportation rates for the years covered in this study

is meager, and economic conditions and

seasonal variations caused rates to fluctuate

considerably. Nevertheless, rates

apparently dropped substantially between 1816

and 1834. They were "fairly

high" before the Panic of 1819, then "declined dras-

tically" during the subsequent

depression. After the economy began to recover,

they continued the downward trend, but

the decline was less severe.62

Between 1815 and 1834 Cincinnati became

a major trade entrep??t within the

Old Northwest. To achieve this

distinction local merchants supported improved

transportation facilities with markets

in the East and New Orleans. Equally as

important was the development of access

routes to the back country which brought

farmers to the city's markets. Business

and political leaders realized that the po-

tential expansion of the city's economy

was limited unless the market area was

expanded. Consequently, they favored

extending and improving existing trade

routes and quickly endorsed those

projects which furthered the expansion of trade.

Residents of the.city, however,

frequently disagreed with farmers in the back

country over proposed routes. Both were

motivated by their own interests. City

residents, merchants in particular,

wanted all projects to terminate at Cincinnati,

and many citizens refused to support

those that did not. Most farmers, on the

other hand, tended to favor cheaper,

more direct routes to the river. With the ex-

ception of roads, they were indifferent

to the fact that a proposed improvement

might by-pass the Cincinnati markets. In

most cases the city won out. It had a

greater supply of capital and more

influence in the state legislature than the rural

areas of the county.

City rivalries, inexperience in proper

construction methods and political logroll-

ing delayed the completion of most

internal-improvement projects. Equally serious

61. Acts of Local Nature Passed at

the First Session of the Twenty-eighth General Assembly of the

State of Ohio . . . (Columbus, 1830), XXVIII, 184; Acts of a Local

Nature Passed at the First Session

of the Thirtieth General Assembly of

the State of Ohio . . . (Columbus,

1832), XXX, 11-14, 15-22,

41-45, 103-109, 117-120, 161-167.

62. Thomas S. Berry, "Western

Prices Before 1861: A Study of the Cincinnati Market," Harvard

Economic Studies, LXXIV (1943), 44.

Internal Improvement Projects 23

obstacles were a lack of capital and an

unwillingness to increase taxes. To solve

these problems, internal-improvements

advocates turned to the state and national

governments. Committed, as were most

Americans to the principles of laissez faire,

they nevertheless were willing to seek

governmental assistance to solve problems

which blocked economic progress. Both

levels of government responded favorably

to local demands for help even though

the amount of assistance was often limited.

Money was received from both the state

and national governments for canal con-

struction, river improvements, and road

building and improvements. Private citi-

zens also invested money and labor in

these projects, and they assumed the major

responsibility for local construction.

The perseverance and ingenuity of local

internal-improvements advocates com-

bined with the financial assistance

provided by the state and national governments

helped to remove a major obstacle to the

city's economic development. Improved

transportation facilities made possible

the establishment of a firm economic base

for the city and stimulated long-term

economic growth.