Ohio History Journal

HENRY KURTZ:

MAN OF THE BOOK

by DONALD

F. DURNBAUGH

At 9:00 A.M. on Monday, January 12, 1874,

Elder Henry Kurtz of Colum-

biana, Ohio, was found in his favorite

rocking chair, his lifeless hands holding

one of his well-loved volumes. The

septuagenarian publisher, communitarian

advocate, and Brethren churchman expired

as he had lived -- as a man of

the book.1

Kurtz was born on July 22, 1796, in the

duchy of Wtirttemberg, the son

of George Jacob (d. 1846) and Regina

Henrietta Kurtz (d. 1857). His

schoolteacher father saw to it that

Henry received a solid classical educa-

tion, but it was the mother, in his

later estimation, who provided him in-

struction in the "nurture and

admonition of the Lord." Though small in

stature, young Kurtz had a quick,

incisive mind and a strong voice. He

would make a good teacher or preacher,

relatives remarked.2

Yet, he did not go on to a German

university to prepare himself for one

of the professions. Instead, in 1817 he

joined the massive migration of

Europeans to the young and bustling

United States of America. The ter-

rors and uncertainties of the Napoleonic

Wars, followed by the repressive

policies imposed by Prince Metternich,

frustrated the plans of many an am-

bitious German during this period.

Freedom and opportunity beckoned

from the New World.

After arrival in Philadelphia, Kurtz

settled in Northampton County,

Pennsylvania, where he was soon offered

a position as schoolteacher. He

filled this position adequately for two

years. Then he felt a calling to pre-

pare himself for the Lutheran ministry.

In reflecting on his feelings at that

time, Kurtz later wrote:

After years of folly and godlessness I

finally thought better of it

and came to the conclusion: I desire to

become a Christian. . . . Soon

afterwards, the intention ripened in me

to become a minister (Christen-

lehrer) . . . and all too soon, my zeal of the newly-converted

brought

me to the work of an evangelical

preacher.3

He presented himself to the Lutheran

General Synod at Baltimore in

June 1819, where he was "directed

to place himself under a suitable in-

structor in order to continue his

studies." As a catechist, he received a call

from the Plainfield congregation in

Northampton County, and took up the

duties of this first charge on August 8,

1819.4

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 173-176

116 OHIO HISTORY

Kurtz soon settled into his work as a

shepherd of the flock. At the

same time he met and married Anna

Catherine Loehr, daughter of a Bavarian

immigrant, the tailor and farmer

Frederick Loehr. The marriage was sol-

emnized on January 9, 1821. Catherine

was to become the mother of their

four sons and a steady support for the

young husband during the troubled

times ahead.5

The formal record of Kurtz's ministry

found in the denominational minutes

indicates that he made excellent

progress in his work. The sessions for

1820 and 1821 heard "favorable

testimonies for Mr. Kurtz, from the con-

gregation of Plainfield." His

labors brought advancement to ordination.

In one year he reported 116 baptized, 55

confirmed, 252 communicants,

and 4 schools in progress.6

Kurtz himself, however, became

profoundly discouraged during this period

over the lack of betterment in the lives

of his parishioners. He had taken

up his pastoral work "full of hope

of the good which he, with the aid of

God, could institute." Yet, he had

to recognize that the parishioner "who

had been a drunkard when he [Kurtz] came

was one still." This realization

caused the idealistic young pastor to

lose his optimism and zeal. He began

to doubt whether he even possessed the

pure evangelical gospel which had

been such a powerful force for good in

early Christianity.7

Just at this juncture, in 1823, a call

came to Kurtz from the German

United Evangelical Church in Pittsburgh

to be pastor. This congregation,

which included both Lutheran and

Reformed members, had first come to-

gether in 1782. Some authorities have

claimed that it is the oldest united

congregation in North America, although

legal incorporation did not come

about until 1821.8

Kurtz bid goodby to his Plainfield

congregation after four years of service

to take up the challenge of the

Pittsburgh pastorate. In his own words,

he looked forward to the new charge with

happy anticipation as offering

a "more promising field of activity

as a preacher, a more appropriate resi-

dence for the education of my children,

a better opportunity for my own

training and advancement in that which

is good and useful." He was in-

stalled as pastor on July 21, 1823,

following the trial sermons and unanimous

congregational vote, with a promised

annual salary of three hundred dollars.9

His early efforts in Pittsburgh in

attacking the accumulated problems

of the congregation were promising. One

serious difficulty had resulted from

a schism between the Lutheran and the

Reformed members and the wounds

had not completely healed. A rapid

turnover of ministers had not made

for harmony in the church. The immediate

problem, however, was financial.

The fiscal position was so confused

that, although it was obvious that

the church was deeply in debt, there was

no clear record at first of what

the amount was.10 Kurtz was

able to retire the debt of nearly five hundred

dollars by a vigorous campaign within

the congregation and by appeals

to more prosperous Lutheran

congregations in eastern Pennsylvania. Im-

pressed by the energy of their new

pastor, the members strongly commended

him at the next Lutheran synodal meeting

in 1824.

HENRY KURTZ 117

With finances in order, Kurtz took up

the more difficult problem of the

spiritual condition of the parish which,

he said, had the sorry distinction

of being the least disciplined

congregation in America. Although warned

against taking the charge, he had taken

up the work at this particular

church because he was eager to show what

he could do to gather a scattered

flock.

His approach was to reformulate the

church discipline, and his proposal

was presented to his church board in May

1824. This was debated point

by point, and finally accepted. The

entire membership then voted to ac-

cept the new discipline, which spelled

out the duties and rights of the

laymen as well as those of the pastor.11

But when Kurtz attempted to im-

plement the covenant, he found himself

faced with resistance and reaction.

Prominent members of the board soon took

exception to the pastor's in-

itiative, which they held to be

"meddling" in the affairs of the congregation.

He was told as much, but this admonition

served only to accelerate his

efforts.12

Dissatisfaction grew into open conflict

when Kurtz attempted to strike

from the membership rolls those who

failed to take communion at least

once a year. The liberty-loving

Pittsburghers considered this action to be

a violation of their freedom to worship.

Several members left in a huff.

The result was that the pertinent paragraph

was stricken from the church

discipline by board action. Later the

pastor's salary was partially withheld

and factions for and against Kurtz

developed. The congregational troubles

were aired before the next synod

meeting.13

Two years later Kurtz acknowledged that

he had not been without

fault in the controversy. He admitted

that his "violent encroachment, un-

sympathetic severity, pride in his own

strength, and trust in his influence

upon the emotions created anger,

irritated the passions, injured love,. . . and

thus I myself helped to overthrow the

edifice."14 The record of the actions

of the congregation before his coming as

well as those of some of the

members in relation to him at this time

indicate that the other side should

also have shared some responsibility for

the problems in the church.

Matters came to a head in the fall of

1825 when Kurtz began to preach

openly the necessity for the

congregation to return to the pattern of the

early Christians. He called for

improvements in their morals and one radical

programmatic change -- the establishment

of a Christian communistic colony

based on the second chapter of Acts.15

Kurtz urged his parishioners to sell

their goods and to join under his

leadership in the formation of a com-

munitarian enterprise similar in nature

to that led by George Rapp in

nearby Economy.16

It is not necessary here to trace in

detail the unhappy church struggle

which ensued between those who followed

Kurtz and those who opposed

him. Throughout the remainder of 1825

and most of 1826 two different

church boards vied for legal possession

of the church building and its books.

At one point in December 1825, Kurtz

offered to resign, but withdrew his

offer when his opponents nailed the church

door shut. He did resign in the

118 OHIO HISTORY

late fall, 1826, in order to prevent a

permanent split in the congregation

and to end the squabble which was

scandalizing the church-going Pittsburgh

population.17

How had a Lutheran pastor become

involved with religious communitar-

ianism, the preaching of which had such

drastic results for his own career?

Kurtz had first become interested in the

concept in 1824 when fifteen

German families from Pittsburgh invited

him to go West with them to

settle on government lands. Although he

declined the request, he began

to think of ways in which such

settlement could be developed on a thorough-

going Christian basis. During this same

period he and those who supported

him within the congregation came to the

conclusion that real Christianity

could be practiced only in separation,

apart from the sullying practices and

distracting influences of the world.

With these themes already running in his

mind, he needed only a catalyst

to begin concrete communitarian

planning. This came in the person of the

famous Scotch reformer, philanthropist,

and community builder, Robert

Owen (1771-1858). The much-discussed

foreigner gave his first American

public lecture in Pittsburgh on January

22, 1825. He had just returned

from southern Indiana where he had

purchased the land and buildings

of the Rappite "Harmony"

community in order to establish his own "New

Harmony." Owen was to be listened

to with deep interest by some of the

most powerful men in the country, and

even granted the use of the halls

of Congress for his addresses.18

Kurtz attended Owen's lecture in

Pittsburgh and was so taken with

the vision of an improved society made

possible by community planning

that he arranged for personal interviews

with the Scotch leader.19 Through

Owen's recommendation, he came into

contact with the Rappite settle-

ment, which, after selling its

flourishing Indiana site, had recently (1824)

moved back to the banks of the Ohio not

far from the original 1805 Penn-

sylvania settlement.

When Kurtz and his friends visited

Economy, they "saw and heard

things which gave them plentiful food

for thought, and for the present

persuaded them that many ills which

seemed unavoidable in the general

society. . . could be completely

disposed of through a different arrange-

ment of the social system." They

assiduously studied the material pub-

lished by Owen, but soon came to the

conclusion that, despite the excel-

lence of his economic ideas, his plan

was doomed to fail because of his

radical rejection of any religious

basis. The publication of Owen's notorious

"Declaration of the Freedom of the

Spirit" on July 4, 1826, which included

freedom from the bonds of matrimony in

the sexual realm, was proof for

Kurtz and his group that Owen was sadly

in error.20

Encouraged by the general enthusiasm

abroad for communitarian ex-

periment but unwilling to link

themselves with the secular Owenite move-

ment, Kurtz and his colleagues issued on

August 10, 1825, a proposal

for the establishment of a "German

Christian Industrial-Community," later

to be designated "Concordia."

This announcement was published in several

HENRY KURTZ 119

German language newspapers in

Pennsylvania. The response was favor-

able enough that Kurtz began in

September 1825 to publish a monthly

magazine dedicated to this communitarian

proposition.

The periodical was significantly named Paradise

Regained (Das Wieder-

gefundene Paradies).21 An ambitious six-point platform was laid down in

the first issue: 1. to expose evils in

church and civil life; 2. to test the

previously-used remedies therefor and

demonstrate their insufficiency; 3. to

note the events of the day which held

significance; 4. to describe primitive

Christianity in its original shape and

form and to publicize it as the only

means of restoring human happiness; 5.

to inform others of the progress of

those communities which apply this

means; and 6. to bring together all

genuine Christians no matter what their

denominational affiliation might be.22

Kurtz laid down the theological base for

the undertaking in a "sermon,"

which in printed form extended over

several issues. Notably influenced

by the religious concepts of Jacob

Boehme (1575-1624) and Gottfried

Arnold (1666-1714), he found the three

major problems of the church

to be the hierarchical structure,

creedalism, and the confusion of Christianity

with philosophy. The threefold answer to

these problems could be found

by improving one's own heart, organizing

Christian communities, and in-

troducing strict discipline in the

church. Complete decay of Christianity

could be staved off only by returning to

the "first love" or simplicity of

the early Christians, the simplicity of

the Gospel, and the simplicity of

nature. Where better, than in America,

the land of religious freedom, to realize

these aims?23

This appeal met with a gratifying

response. Nearly fifty families expressed

orally or in writing their willingness

to join such a community within

the month, but the Concordia leadership

felt that such an important step

could hardly be taken so precipitously.

Through the medium of the Para-

dise Regained the leaders would first gather friends and funds, and

in

the meantime look for a suitable

location. Two possibilities for settlement

in Pennsylvania were presented -- one on

the west branch of the Susque-

hanna (evidently the Juniata Valley was

meant), the other on the Allegheny

River near Lake Erie.

Despite the optimism expressed in the

columns of the periodical, Kurtz

himself was not in an advantageous

position. This was the period of the

bitter strife in the congregation of

which he was still pastor, despite ir-

regular payment of salary. The costs of

printing the paper were also burden-

some. By the first of the next year

(1826) his financial situation was most

uncomfortable. In January he appealed to

George Rapp, the Harmonist

patriarch, for an advance of one hundred

dollars which would enable him

to continue issuing the periodical

without the necessity of raising more

money from his friends; he was prepared

to encumber his piano, horse,

books, and furniture as security for the

loan.

It is not clear whether the request was

granted. However, Rapp evidently

invited Kurtz (during a visit the latter

made in February or March) to

join the Economy community as a teacher,

since Kurtz raised details about

120 OHIO HISTORY

books he would need as texts to run a

school along Pestalozzi methods.

But he decided, finally, not to go to

Economy. Given the pastor's strong

will, it could well be that he preferred

to carry through his own communal

project rather than to accept Rapp's

leadership.24

Later in March 1826, Kurtz proceeded

with the publication of an ab-

breviated draft of a constitution for

the Christian Industrial Community

(Concordia). The draft leaned heavily on

the model of Owen's New Harmony,

the constitution of which had been

published by Kurtz earlier, with an

obvious difference in the strong religious

orientation of the Concordia pro-

posal. Rules for the incorporation of a

"Preliminary Community" with

four different classes of members

depending upon the amount of capital

invested were announced at the same

time.25

In late May, June, and July 1826, in

conjunction with the annual meet-

ing of the synod at Berlin,

Pennsylvania, Kurtz travelled through the

eastern states seeking support for his

communitarian idea. Those who had

no interest in joining the enterprise

personally were urged to support the

plan with gifts of money and books, the

latter to become the basis of the

library which played a prominent role in

the concept of Concordia.

One of the most encouraging visits was

to the Dunker colony of Bloom-

ing Grove, north of Williamsport,

Pennsylvania. Kurtz had previously re-

ceived correspondence from the leader of

the community, the German-born

Dr. Friedrich Conrad Haller (1752-1828).

On his visit he was much im-

pressed by the high quality of Christian

life there in the isolated setting

among the trees. In later years he was

to remain in touch with the Blooming

Grove Dunkers.26

On the whole, however, the trip was a

failure. Kurtz wrote a most dis-

couraged letter back to his friends in

Pittsburgh in which he candidly ad-

mitted that he had met with so much

suspicion that often he did not have

the will to speak on behalf of

Concordia. It was rumored that the plan was

based on speculation for private profit.

Even worse, the troubles which

Kurtz was experiencing with his

congregation made it appear as if the com-

munity-idea was a means to improve his

own shaky fortunes. So keenly did

he feel the rebuff that he made a solemn

renunciation of any future office

or position of leadership in the community

when it was formed.27

During Kurtz's absence a meeting was

called by his friends to be held

in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, in

September. Three points were to be de-

cided. First, how many persons were

actually ready to enter Concordia;

second, how much capital was available;

and third, where and when the

first settlement was to be located. A

certain impatience with delay was

evident.28 The Greensburg

meeting was supplemented by another in Spring-

field, Ohio, in October 1826. It was

found that thirty families had reported

and were ready to enter the community;

three to four thousand dollars

of capital had been pledged by those not

present at the meetings and

"several thousand" dollars

were promised by the signatories of the report.

Land on the Tuscarawas River near New

Philadelphia, Ohio, had been

chosen as the site of the colony.

Another meeting was called for February

HENRY KURTZ 121

1827 in Springfield to be "the last

preparatory meeting with the help of

God for erecting our institution."29

The signers of the report along with

Kurtz were Johann G. Mayer,

George Ziegler, Michael Gebhard, J.

Jacob Rutlinger, and George Mayor.

Mayer, Ziegler and Rutlinger all had had

some prior connection with the

Rappite movement. Mayer was a friend and

correspondent of George Rapp;

Ziegler had purchased the first

settlement of the Rappites in Beaver County,

near Pittsburgh (although in the end he

was not able to raise all the money

promised); Rutlinger was associated with

a group who hoped to gain some

of the Harmony wealth by legal action.30

Kurtz now broke completely with the

Pittsburgh congregation and some-

time between October and January moved

with his family from Pennsylvania

to Stark County, Ohio, near the

anticipated site of Concordia.31 They had

a difficult time for a period, and were

dependent upon gifts of food from

a neighbor. This was a time of

provisional nature, of waiting until the

community could be established. However,

there is some indication that

Kurtz was changing his mind about the

wisdom of the communal enterprise.

While waiting, he occupied himself with

the second volume of his periodical,

printed in Canton by John Sala. It was

given the title The Peace Messenger

of Concordia (Der Friedensbote von

Concordia).32 The four aims listed in

the first issue all centered on peace:

peace with God; peace in the family;

peace with neighbors; peace in the

Church. Almost as an afterthought the

editor-publisher mentioned that the Peace

Messenger would "report from

time to time material that is

presented" to it about developments on Con-

cordia.33 The contents were

not limited to communitarianism, but were de-

signed to be of interest to the broader

German population and included

essays, stories, and poetry.

In answer to queries from friends, Kurtz

replied that his aims were not

sectarian; he still considered himself

to be a Lutheran and a member of

the synod. The 1827 synod of western

Pennsylvania noted that "Pastor

Kurtz was absent without excuse."

His whereabouts were thought to be

New Harmony.34 About this

same time he had an interesting sermon

printed in eastern Pennsylvania. The

sermon on the theme, "God is love,"

was dedicated to his "dear

congregation of Northampton and all of his

friends of that area." It was

perhaps meant as a kind of valedictory to his

career as a Lutheran pastor.35

The next development in the Concordia

story is found in the published

report of a meeting of those interested

in the community that was held in

Canton on September 28, 1827. Kurtz

provided a summary history of the

movement and made a full accounting of

subscribers, capital raised, and

books donated. He made it clear that he

wished to remove any possibility

of suspicion that any money donated had

been used to defray his own needs.

The actual amount in cash raised had

been $367.50; paying subscribers

totaled 237. He declared that he could

not continue much longer with the

publication, which was not meeting

expenses, unless a large number of un-

sold issues were purchased. This would

enable him to buy a house in Canton

122 OHIO HISTORY

in which a school could be established.

It is evident from the tone of the

report that hope was waning, even in the

irrepressible heart of Kurtz, that

the community would ever become more

than a proposal on paper.36

The final number of the Peace

Messenger (December 1827) contains

the notice of the establishment of

another community in Springfield Town-

ship, Columbiana County (later Mahoning

County), Ohio. Kurtz welcomed

the new effort, named Teutonia,37 and

said that he was willing to donate

the monies he had collected for

Concordia to it, thus fulfilling the pledge

made to the donors. The community was

led by Peter Kaufmann (1800-1869),

at one time a teacher for Rapp. Kaufmann

had left Economy because he

did not share the religious views of the

German patriarch, which included

eschatology, celibacy, and a strict

discipline under autocratic leadership.

The charter members of Teutonia included

disgruntled Rappites and some

of Kurtz's erstwhile associates. It

seems that they shifted their loyalties

to the Kaufmann-led venture when the

lack of progress of Concordia be-

came evident. Following an early period

of success, Teutonia was dissolved

amicably in 1831, and a division of

assets was made among the members,

who resumed private life.38 This

was the prosaic end of the vision of Con-

cordia. Kurtz penned the obituary to his

communitarian dreams when he

commented on Teutonia, "I am not

minded to institute anything of this

nature myself."39

Despite this second failure, Kurtz had

found something in northeastern

Ohio which was to reshape his entire

life. The religious pilgrimage which

had taken him into the Lutheran ministry

and then toward religious com-

munitarianism had brought him also into

contact with the German Baptist

Brethren or Dunkers (now Church of the

Brethren).40 Here he found a

movement to which he could give his

life, as the Dunkers' concern for

disciplined church membership and

conscious patterning of church practices

after the life of the early Christian

church incorporated the ideals for which

he had been contending.

It is not known precisely how Kurtz came

in touch with the Brethren.

As a resident of eastern Pennsylvania,

where their heaviest concentration

was found, he could have learned of them

during his early ministry in

Northampton County. His pleasant

encounter with the Dunkers of Bloom-

ing Grove has already been related,

although the communitarian aspect of

their life was atypical for the

Brethren.41 The first definite indication of his

shift in religious views is found in the

criticism he made of the new Teutonia

community for not stressing three-fold

immersion baptism. More pointedly,

he devoted most of the last issue of the

Peace Messenger to a series of

ninety-five questions and answers on

this topic, perhaps a reflection of

Luther's ninety-five theses. Taking the

pseudonym "Christian Heimreich,"

he emphatically rejected infant baptism

and defended the institution of

believers' baptism.42

Elder George Hoke of Canton baptized

Kurtz, and it may well be that

he also had a part in his conversion.43

Hoke was a staunch Brethren leader,

noted for his doctrinal clarity and

conviction; the friendship between the

HENRY KURTZ 123

two men was a deep and lasting one. The

baptism took place under a large

tree on the Royer farm in Stark County,

Ohio, on April 6, 1828. Presum-

ably, Mrs. Kurtz was baptized on the

same occasion.44 According to a

daughter of Elder Hoke, Kurtz wore his

Lutheran pastoral robe, and upon

rising from the water after immersion

allowed the gown to slip from his

shoulders and float down the stream,

thus symbolizing his rejection of his

past office.45

Two years later Kurtz was elected to the

"free ministry" of the Brethren,

involving the ministerial duties of

preaching and visiting without remuner-

ation. Expenses could be reimbursed if

the minister was not financially able

to bear them himself. (The employment of

salaried pastors did not become

common among the Brethren until the turn

of the century.) Eleven years

later he was placed in charge of the

Mill Creek Church in Mahoning County.

This responsibility involved a

forty-mile horseback ride once a month

until the spring of 1842, when he moved

his family to a farm near Poland

in that county. On September 26, 1844,

he was ordained an elder, the

highest church office in the basically

congregational Brethren polity. He

served at Mill Creek faithfully for

thirty years, and was held in great love

and respect by the members. Under his

leadership the membership grew

steadily in size, despite repeated

withdrawals of those who joined the general

westward migration of the time.46

The striking change in Henry Kurtz's

religious affiliation did not go

without notice. Relatives and former

parishioners in Northampton County

were particularly shocked at his

"apostasy." They suffered "sore distress

that one so dearly beloved should make

such a shipwreck of his faith." In-

deed, one of his wife's cousins,

Friedrich Peter Loehr (1803-1880), resolved

in the summer of 1828 to visit and reconvert

him. Despite two days of in-

tensive conversation and pleading, Loehr

failed in the attempt. On his

way home he mulled over the discussion, became

convinced that his rela-

tive was right, and returned to him to

request baptism! Loehr, himself,

later became a Dunker preacher and

elder, active in the ministry in In-

diana and Michigan.47

From 1829 on the histories of Kurtz and

the Brethren merge. For Kurtz,

the Brethren were people whose lives and beliefs

coincided with his under-

standing of God's will for the church.

For the Brethren, Kurtz proved to

be a leader whose influence has been

reckoned as the most powerful in

shaping the course of the denomination

in the nineteenth century.48 The

key to his leadership is found in the

publishing enterprise he established.

Inasmuch as Kurtz could not expect a

means of livelihood to follow from

his affiliation with the Brethren, he

decided to support his family by a com-

bination of farming and printing. First

at Osnaburg and then near Poland,

Ohio, he farmed to provide a living for

his family, but lived for his publishing

activity.

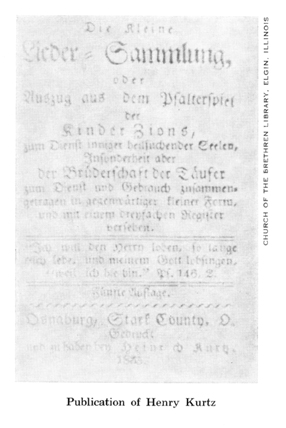

The first book credited to him is Die

Kleine Lieder-Sammlung, printed in

Canton by Solomon Sala in 1829, but

issued originally in Hagerstown in

1826. He published at least seven later

editions of this little songbook,

124 OHIO HISTORY

which became standard among Brethren

congregations.49 In the early 1830's

Kurtz secured a press of his own, most

likely from the Sala family of Canton.

The first published item (1832) seems to

have been a primer or ABC book,

with Osnaburg given as the place of

publication. He reprinted this book

at least twice later.50 The following

year he printed a large volume con-

taining a portion of the works of Menno

Simon in German translation.

In the preface to the book by the

sixteenth century Anabaptist leader,

Kurtz noted that his purposes in

publishing this work were twofold: to

earn an honest living for his family and

to be of help to his fellow pilgrims

on the Christian way. He had been given

a complete set of Menno's writ-

ings in Dutch, which he hoped to

translate and print at half-year intervals.

As no further volume in the projected

series is known, it may be assumed

that the venture was not profitable

enough for him to carry on after the

first attempt.51 Two years later he

printed another Mennonite book, this

time upon the initiative of two

Mennonite ministers, Daniel and Peter

Steiner of Wayne County, Ohio. It was a compilation

of morning and eve-

ning prayers and hymns written by

Anabaptist martyrs.52

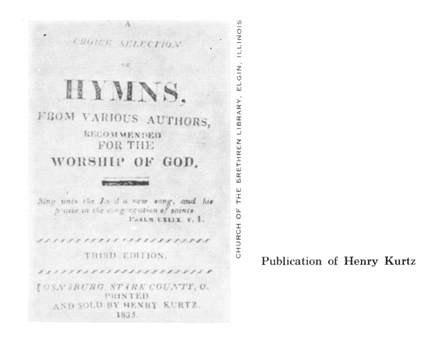

Also in 1833-34 Kurtz attempted a weekly

paper, Das Wochenblatt,

which, however, failed "for want of

patronage."53 He found a more valuable

item in an English counterpart of the

small German hymnal, the Choice

Selection of Hymns, from Various

Authors, Recommended for the Worship

of God. This was readily accepted among the Brethren and became

known

as the hymnal of the "Far Western

Brethren," in which "far west" meant

the present Midwest. Six later editions

of the Choice Selection are known,

and more may have been printed.54 In

1836 the printer tried once more

to issue a periodical. This time it was

a monthly entitled Testimonies of

Truth or Zeugnisse der Wahrheit. It featured German and English texts

in parallel columns. Each issue had

twenty-four pages and sold for six

and one-quarter cents. A year's

subscription, if paid upon receipt of the

first number, cost fifty cents. As only

the first two issues are extant, this

venture likely failed to find

subscribers.55

More successful was a New Testament in

the German translation of Martin

Luther. This significant publication,

among the earliest biblical publications

in the state of Ohio, included a listing

of the "so-called epistles and evangels,"

or prescribed texts, for each Sunday.

Kurtz, as a former Lutheran pastor,

could not entirely omit them, but he

felt obliged to state that they "by no

means belong to the New Testament."56

In 1837 he was appointed clerk of the

Brethren yearly meetings, or an-

nual conferences. This post brought the

opportunity of printing the minutes

of the meeting, held at Pentecost each

year. Beginning in 1837, Kurtz

published the minutes in both German and

English editions, usually with

both languages in the same booklet,

although occasionally they are found

in separate editions. He also printed at

least one year's minutes for the

German Reformed Synod of Ohio.57

Another aspect of Kurtz's printing

activity was the medical guide--

Americanisches Noth-und

Hulf-Buchlein... (1837)--which may

also have

|

HENRY KURTZ 125 |

|

|

|

been published in English. The home remedies were based upon the work of an unnamed Virginian physician. This guide has been included in a re- cent study of important early American compilations of folk cures.58 That the business, along with the farming, must have prospered is in- dicated by Kurtz's decision to return to Germany for a visit in December 1838. He was eager to see his parents again for what he considered to be the last time. He also wanted to acquaint himself with some of the newer religious movements and to "preach the word where there was an open door." One door he found open was in Switzerland, where he contacted the Neutaufer or Froelichianer in the canton of Zurich. This group, led by Samuel Hermann Froelich (1803-1857), rejected the established Reformed church, military service, infant baptism, and other accepted church prac- tices, and for these views suffered severe reprisals. After convincing nine of this group of the necessity for immersion baptism, Kurtz, on April 14 and 15, 1839, baptized them, among whom was George Philip Rothenberger (1802-1881), a minister among the Neutaufer. Froelich, who understand- ably opposed this activity, won back some of the baptized, but several families held firm and moved to the United States to unite with the Brethren. Rothenberger became a neighbor and friend of Kurtz in Stark County.59 After his return from Europe in July 1839, Kurtz resumed his farming and printing. In 1842 he moved to Mahoning County to be closer to the Mill Creek congregation. He established near Poland his print shop, which measured twenty by twenty-four feet, in a "spring house" built over water |

126 OHIO HISTORY

for the cooling of foods.60 However, he

could not give all of his time to his

private interests, as his ministerial

duties entailed many lengthy trips.

An example was his journey to Virginia

in April and May 1845, with a

fellow Ohio elder. They were joined in

their visits to congregations there

by John Kline (1797-1864), a leading

Brethren churchman. A sermon

preached by Kurtz on this trip was noted

in outline form in Kline's diary.

The major point was the necessity of

ministers to avoid the search for

glory; they should rather seek to honor

God in all humility. The trip was

timed to include the Brethren yearly

meeting held on May 9-10 in Roanoke

County, Virginia. One year previously he

had been named to the "standing

committee" of elders, the inner

circle of trusted churchmen who prepared

the business agenda for the

conference.61

The most important publishing venture

for Kurtz and for the Brethren

was the church periodical he began in 1851--The

Gospel Visitor.62 This

periodical, although later merged with

others and published in various lo-

cations, is still being issued, making

it one of the oldest American denomina-

tional journals. Why did Kurtz attempt

this publication when three of a

similar nature had failed? He was

convinced of the burning need of such

a paper for the good of the church. As

the Brethren migrated across the

country, it was no longer possible to preserve

the unity of the brotherhood

by personal visits. Another method was

needed. A schism in Indiana over

doctrinal issues demonstrated clearly to

him the need for a forum where

problems of the faith could be shared

and answers communicated.

Just as clearly as he saw the need for a

paper, he saw the obstacles facing

him. Such an enterprise would be opposed

by the more conservative elders,

who would consider it a worldly

innovation. The experience of Abraham

Harley Cassel (1820-1908) of

Harleysville, Pennsylvania, a supporter of

the project, is indicative of some of

the reactions Kurtz was trying to fore-

stall. This friend had had more than

fifty families in his congregation in-

terested in subscribing to the proposed

periodical until a Lancaster County

elder, who came to Harleysville for the

fall love feast, spoke so strongly

against the idea that not many of the

local people were still willing to fol-

low through.63

Before printing the first issue, Kurtz

set out to overcome this suspicion

of the Brethren. In July 1849 he sent

out queries to a large number of con-

gregations explaining his idea and

asking for subscriptions. He needed

the assurance of a definite number of

subscribers in order to undertake the

sizable financial risk of beginning the

enterprise. In a letter to Cassel he

disclosed that, of those who replied,

nine-tenths wished to have solely an

English edition. A German edition would

have to be issued separately. "All

I hope for," wrote Kurtz, "is

that the German and English should breathe

one spirit of love, union, and forbearance."64 The

editor's hope was to be

able to print trial copies before the

1850 yearly meeting and submit them

for the decision of the conference. This

hope was not realized, however,

because of illness in the family on whom

he was dependent for assistance.

Instead, the meeting's response to the

query that asked: "Whether there

|

HENRY KURTZ 127 |

|

|

|

is any danger to be apprehended from publishing a paper among us?" was to table the request for one year.65 This apparent evasiveness notwithstanding, Kurtz decided to go ahead with the project until he was specifically forbidden to do so by the church. He therefore issued the first number of The Gospel Visitor in April 1851 and sent it to those who he thought would be willing to introduce the publication in their neighborhoods. Excerpts from his preface give further insights into his motives in beginning the paper: Thousand of presses are daily working in this our country, and are issuing a miltitude of publications, some good, some indifferent and some, alas! to many absolutely bad and hurtful. They find their way not only in every village, but we may say, into every family or cabin in our land . . . Now if this be the case, should we not use every means in our power, to counteract the evil tendencies of our time, and to labor in every possible way for the good of our fellowmen, and for the glory of God and his truth as it is in Christ Jesus? . . . But we are asked: What do you want to print, and what is your object? We will try to answer in a few words. We are as a people devoted to the truth, as it is in Christ Jesus. We believe the church as a whole, possesses understandingly that truth, and every item of it. But individually we |

128 OHIO HISTORY

are all learners, and are progressing

with more or less speed in the

knowledge of the truth. For this purpose

we need each other's assistance.

But we live too far apart. If one in his

seeking after a more perfect

knowledge becomes involved in

difficulty, which he is unable to over-

come, this paper opens unto him a

channel, of stating his difficulty, and

we have not the least doubt, but among

the many readers there will be

some one, who has past the same

difficult place, and can give such ad-

vice, as will satisfy the other.66

The anxiously awaited decision of the

1851 yearly meeting read: "Con-

sidered, at this council, that we will

not forbid Bro. Henry Kurtz to go on

with the paper for one year; and that

all the brethren or churches will im-

partially examine the Gospel Visitor,

and if found wrong, or injurious,

let them send their objections at the

next Annual Meeting."67 Kurtz then

proceeded with his publication, which

included discussions on church his-

tory, congregational news, doctrinal

questions, and correspondence in a

neatly printed periodical. The

subscription list grew steadily.

The annual meeting of 1852 decided that

in consideration of both positive

and negative reactions received, the

paper "could not be forbidden" and

that it should continue to "stand

or fall on its merits." One year later the

same body closed discussion of the

matter by resolving that: "Inasmuch

as the Gospel Visitor is a private

undertaking of its editor, we unanimously

conclude that this meeting should not

any further interfere with it."68

Beginning in April 1852, Kurtz published

a companion journal in German,

Der Evangelische Besuch. Although not identical with The Visitor, it used

much of the material from the English

edition in translated form. As a

native German and one persuaded of the

merits of German culture, he

was concerned that the use of German might

be lost among the Brethren.

For this reason he persevered with this

edition until 1861, although he

lost money on it most of the time.69

From the start of this latest endeavor,

Kurtz began looking for editorial

colleagues who could help him and his

family with the substantial labors

of issuing a twenty-four page monthly.

In 1855 he found the right man in

the person of James Quinter (1816-1888).

In 1856 Quinter moved from

Fayette County, Pennsylvania, to Poland

and became assistant editor as

well as assistant clerk of the Brethren

annual meetings. As Kurtz was still

much more at home in his native German,

it was an immense help to have

an English-trained aide. The assistant's

chief duties were writing and editing

suitable material in English. He proved

to be so apt that he succeeded

Kurtz as editor when the latter retired,

and later served in the same capacity

for several other influential Brethren

papers.70

In 1856 Henry Holsinger (1833-1905)

joined Kurtz for a time as an ap-

prentice. The young man's career

included the publication of the first suc-

cessful Brethren weekly, the first youth

paper, and the first hymnal with

musical notation. In his papers, Holsinger vociferously

championed church

reform and progressive ideas, so much

so, in fact, that he was finally ex-

pelled by the Brethren in 1881. He took

a large group with him and founded

the "Brethren Church" or

"Progressive Brethren."71

HENRY KURTZ 129

In his lengthy history of the

"Tunkers," Holsinger published some glimpses

of Kurtz and his home life:

Elder Kurtz was a German of the Teutonic

caste .... He was an ex-

cellent German reader, and eloquent in

prayer in his mother tongue,

but hesitated and almost stammered in

English. He was very religious

in his forms, and held family worship

every evening, and frequently in

the morning also. Under his charge I

learned to exercise in prayer....

Brother Kurtz was quite a musician,

vocal and instrumental, and had

an organ in the house, but rarely used

it. I shall long remember one

occasion on which I heard him perform

and sing one of his favorites.

I went to the house, where the editorial

sanctum was, on business con-

nected with the office. After entering

the hall, I heard music, and finding

the door ajar, I stopped and listened

until the hymn was complete,

much delighted with the strains.72

As the subscription list of the Gospel

Visitor grew and the inconvenience

and isolation of the printing office

became more burdensome, the publisher

moved his family to the town of

Columbiana, Ohio, in June 1857. Also

under consideration was the

establishment of a school and seminary. This

plan did not materialize in Columbiana,

but Kurtz and Quinter did es-

tablish an academy at nearby New Vienna,

in October 1861. The school

flourished until the exigencies of the

war caused its closing in 1864.73

Although the periodical took most of

Kurtz's attention, he did publish

other material as well. In that day of

intense denominational rivalry it is

not surprising that a limited amount of

polemical literature issued from

his press. One interchange involved the

Mennonites, who shared many be-

liefs with the Brethren, but differed on

the manner of baptism.74 A Men-

nonite publication was answered by John

Kline, the Virginia Brethren

leader and friend of Kurtz, in a

sixteen-page tract (1856). This called forth

a 300-page book by the Mennonite editor

of the previous publication. Kline

responded with a booklet of some seventy

pages. His literary duelist com-

posed a 316-page answer to Kline's

rebuttal, which, however, was never

published. Perhaps cooler heads agreed

that the effort was out of propor-

tion to the problem.75

Possibly issued in connection with the

same controversy was an undated

tract on Christian baptism by Menno

Simons, which immersionists have

contended calls for immersion baptism.

Of course, if it could be demon-

strated that the man for whom the

Mennonites were named believed in

immersion, then it would seem incumbent

on later followers to accept

the practice. Mennonite scholars,

however, deny that Menno so taught.

Although no place of publication is

given on the tract, it is clearly one of

Kurtz's publications.76 To

show that he had not lost his hard-won irenic

spirit, it may be noted also that in

1861 he republished the well-known

pedagogical work of the Mennonite

colonial schoolmaster, Christopher Dock.

This third edition was printed by Kurtz

for a committee of Ohio Mennonites.77

One year earlier Kurtz had brought out a

new translation of the oldest

Brethren writings -- two treatises by

the first Brethren minister Alexander

Mack (1679-1735). Quinter polished the

editor's English translations, and

also provided a "memoir" of

the life of Mack. Following a technique used

130 OHIO HISTORY

in earlier publications, the two

treatises were printed in parallel columns

of English and German.78

The last issue of volume fourteen of The

Visitor of December 1864 in-

cluded a statement headlined

"Valedictory," signed by the senior editor.

Considerations of health and age, he

wrote, led him to turn over the pub-

lication to Quinter and to his son,

Henry J. Kurtz, for a nominal sum. He

hoped to contribute from time to time,

but wished to "retire from active

editorial labors."79 He,

nevertheless, had another large project in mind,

one for which he had been gathering

material for many years. This was to

be a Brethren's Encyclopedia, which

would contain decisions of annual

meetings, early Brethren history, and

other important data in one compact

reference work. It was completed in

1867. Some have claimed that the ency-

clopedia, despite its obvious merits,

did not become generally accepted among

the Brethren because of the frequency

and freedom of the editorial judg-

ments employed in introducing the

selections from the annual meeting

minutes. The book, nonetheless, was

reprinted by a Brethren group as late

as 1922.80

Kurtz's last publication on behalf of the

church was the same as his

first -- a hymnal. As chairman of a

committee of the Brethren assigned

to the task, he played a major role in

compiling the Neue Sammlung von

Psalmen, Lobgesangen und Geistlicher

Lieder (1870), an arduous task

made more difficult by illness.81

The final years of Kurtz's life were

peaceful, although his health was

not good. One break in the fairly

uneventful flow of his days was a last

visit to Germany, undertaken in December

1867, in order to see his sister.

The sole remaining member of his German

family, she had suffered a para-

lytic stroke.82

In January 1871 he celebrated with his

wife their fiftieth wedding an-

niversary. He now had leisure to enjoy

his grandchildren, one of whom left

the following description of him:

He was a small man with a hump on his

back, and he always used a

cane when he walked. He took short,

quick steps. He had rather long

white hair, but the top of his head was

bald and in cold weather he

always wore a little silk cap to cover

that bald spot. He had long white

whiskers .... He used to get books to

read that were very interesting.

I remember the first one I brought home.

After I was through reading

it he said he wanted to read it too. He

wanted me to write what I had

read about, and in my own words. Well, I

did the best I could, for I loved

him.... Sometimes he played on the organ

and enjoyed teaching me

some little songs on Sunday afternoon

after Sunday School. He gave

me many good suggestions and rules to

follow, which I remember and

some which I have followed all my life.83

Although Kurtz resigned his duties as

clerk of the annual meeting in

1862, he remained active in the local

congregation. The day before he died

he preached a sermon. His death in 1874

was widely noted in the Brethren

periodicals. One typical notice under the title,

"Sad Intelligence," ran:

We have received the sad news of the

departure of Eld. Henry

Kurtz. He died very suddenly.... Eld.

Kurtz was extensively known

|

throughout the brotherhood as the originator of the Gospel Visitor, the pioneer paper of the brotherhood.84 And so died Henry Kurtz. After a stormy early career, he found fulfill- ment with the Brethren. They in turn were led by his tactful but persistent proddings toward higher education, missions, an educated ministry, and other reforms. As he had intended, the Gospel-Visitor played a major role in preserving unity of the church, especially through the trying period of the Civil War, which divided most Protestant denominations. As a preacher, publisher, and progressive leader, Henry Kurtz left his mark.

THE AUTHOR: Donald F. Durnbaugh is Associate Professor of Church History at Bethany Theological Seminary. |