Ohio History Journal

JOHN BROWN.

RY C. B. GALBREATH

INTRODUCTION.

"John Brown's body lies moldering

in the grave

But his soul goes marching on."

So sang the Twelfth Massachusetts

Regiment as it

marched south to put down the rebellion

and so have

sung other regiments and men who never

belonged to

any military organization in almost

every part of the

North and West since the outbreak of

the Civil War.

It is remarkable how old John Brown

holds his place

in the history and literature of his

country. His name

and deeds have been the theme of

divided opinion and

heated disputation, of eloquence and

song, of eulogy

and detraction, of generous praise and

scathing crit-

icism. If his spirit could speak today

he might truth-

fully say, "I came not to send

peace but a sword."

Those who comment upon the part that he

acted in the

"storm of the years that are

fading" find themselves

arrayed one against another when they

come to pass

judgment upon his deeds, and not

infrequently the critic

exemplifies "a house divided

against itself" and ex-

presses in the same estimate opinions

condemnatory and

laudatory.

In undiminished measure his fame

endures, however.

Even at this late day interest in

"Old John Brown of

Osawatomie" persists, and since

the beginning of the

new century at least four pretentious

volumes have

(184)

John Brown 185

been devoted to his life and character.

His name occurs

at frequent intervals in current

periodical and news-

paper literature and a place for him in

the history of the

Republic seems to be assured.

In Ohio a distinct revival of interest

in this re-

markable man has followed the transfer

of rare relics,

which once belonged to John Brown and

his warrior

sons, to the Ohio State Archaeological

and Historical

Society. These include guns, swords,

uniforms, survey-

ing instruments, autograph letters,

photographs and

other items ranging from bullet molds

to locks of the

hair and beard of this sturdy old

warrior in the anti-

slavery cause.

These papers and relics are duly

authenticated.

They were for a long time in the

possession of Captain

John Brown, Jr., the eldest son of John

Brown, who

lived after the war at Put-in-Bay,

Ohio, where he died

in 1895. They then passed into the

possession of his

daughter who married Mr. T. B.

Alexander and who

still resides at Put-in-Bay. She and

her husband trans-

ferred these rare and precious relics

to the custody of

the Society. The numerous visitors who

almost daily

come to the museum and library building

of the Society

invariably pause to view these

souvenirs of the stirring

times in Kansas and at Harper's Ferry.

This manifestation of interest has led

the writer to

attempt a series of articles for the

QUARTERLY on "John

Brown and His Men From Ohio." Of

John Brown

himself little remains to be written.

His entire life from

birth to execution has been subjected

to the searching

investigation of friend and foe. It is

really remarkable

with what patient research the

different steps in the

career of this man have been followed

and with what

186 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

wealth of detail they have been

recorded. It remains

for the writer only to present that

record in outline and

emphasize such portions as relate to

John Brown's life

in Ohio. This is the necessary

background for the con-

templated sketches of his men from this

state. A gen-

eral knowledge of the character and

purposes of the

leader is essential to an understanding

of the motives

and actions of his followers.

Fortunate is the man who has a

sympathetic biog-

rapher. Autobiography not infrequently

leaves a more

satisfactory impression with the casual

reader than does

biography. Someone has observed that Benjamin

Franklin showed his wisdom in leaving

to posterity a

carefully prepared record of his life

which has become

a classic in our language. Other

writers have been less

classic and some of them less lenient.

The first biog-

raphy of the subject of this sketch,

entitled The Public

Life of Captain John Brown, was written by James Red-

path, a man in hearty sympathy with

Brown and so

closely associated with him in Kansas

that he may be

classed among John Brown's men. His

book bears the

copyright date of 1860, had a wide sale

and produced a

profound impression. The author in a

brief period col-

lected a wealth of material favorable

to his hero whom

he valiantly defends against attack

from whatever

quarter. It is difficult even at this

late day to read this

record without living again in the

times in which it was

written and yielding to the fervent

appeal presented by

the author. To Redpath, John Brown was

always right

and the sainted martyr of his

generation.

Redpath was a newspaper correspondent

and a man

of considerable literary ability. He

witnessed the stir-

ring scenes in Kansas but was not at

Harper's Ferry.

John Brown 187

A poem entitled "Brown's Address

to His Men," evi-

dently written by himself, reveals

something of the

spirit of the anti-slavery warriors in

Kansas. We quote

here the introductory and the

concluding stanzas:

They are coming--men, make ready;

See their ensigns- hear their drum;

See them march with steps unsteady;

Onward to their graves they come.

We must conquer, we must slaughter;

We are God's rod, and his ire

Wills their blood shall flow like water:

In Jehovah's dread name-Fire!

While Redpath's book is a valuable

contribution to

the history of the times, it was

written too soon and in

the midst of an excitement so intense

that inaccuracies

naturally occur and it cannot claim the

highest authority.

In another volume, Echoes From

Harper's Ferry,

issued in the same year, this author

has performed a

valuable service by collecting and

publishing in perma-

nent form the expressions of eminent

men and women

on the tragedy that closed with the

execution of Brown

and a number of his followers. This

includes the views

of Thoreau, Emerson, Theodore Parker,

Henry Ward

Beecher, James Freeman Clarke, William

Lloyd Garri-

son, Victor Hugo, Mrs. M. J. C. Mason

of Virginia and

Rev. Moncure D. Conway of Cincinnati.

There are

quotations from scores of others almost

equally promi-

nent and a collection of the

correspondence of John

Brown. Ohioans will find interest in

the fervid and

prophetic address of Conway, which is

full of the senti-

ment that pervaded the ranks of

anti-slavery men in

Ohio under the stress of the times.

In John Brown, Liberator of Kansas

and Martyr of

Virginia, F. B. Sanborn, the contemporary and associate

188

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

of Brown, has presented in over 600

compactly printed

pages the life and the most complete

collection of the

letters of Brown that has been

published. This work

has gone through four editions, the

last of which bears

the date of 1910. Mr. Sanborn was the

well known

writer of Concord, and no study of the

life and times of

Brown can satisfactorily be made

without frequent ref-

erence to this book, written by his associate

and friend.

Like the work of Redpath, this volume

has been pre-

pared by one in thorough sympathy with

the purposes

and achievements of Brown and must be

regarded as

the testimonial of a devoted lifetime

friend.

Richard J. Hinton, another associate of

Brown's, in

1894 published a most interesting

volume entitled John

Brown and his Men. The appearance of this contribu-

tion was most fortunate. In Kansas and

at Harper's

Ferry, Brown was so completely the

dominating figure

of the tragic scenes through which he

passed that sight

is almost lost of his followers. It is

fortunate that one

of these followers who personally knew

the men that

served under John Brown should collect

all the avail-

able material in regard to the lives of

these associates.

We are apt to think of them sometimes

as men like

Brown himself, to overlook the fact

that they were all

much younger, in fact a majority of

them might be

termed boys, for some of them were not

out of their

teens and most of them had not reached

their thirties.

Though younger they were in thorough

sympathy with

Brown. Seven of them were his own sons.

Almost

without exception they had acquired the

rudiments of

an education in the common schools of

their day and

some of them, like Kagi and Cook, were

men of wide

reading and some literary ability,

while Richard Raelf,

John Brown 189

a wayward son of genius, was a poet

whose writings

are altogether worthy of the attractive

volume in which

they have been published with a memoir

of his life. For

our purpose this volume by Hinton has

an especial value

as it contains matter and references

that will be very

helpful in contemplated sketches of

Kagi, the Coppoc

brothers and John Brown's sons, six of

whom were born

in Ohio.

In 1911 Houghton Mifflin and Company

issued a

substantial and attractive volume of 738

pages entitled

John Brown, a Biography Fifty Years

After, by Oswald

Garrison Villard, a grandson of William

Lloyd Garri-

son. This work is the result of

research study extend-

ing over more than three years. The

author seems to

have consulted every available source

in his industrious

quest and he came into contact by

personal visit or letter

with practically all of the survivors

who had been asso-

ciated with Brown or had been present

at the time of the

Harper's Ferry raid and the execution

that followed it.

In the preface of his book he states

his purpose in lan-

guage that needs no explanation. He

says in part:

"Since 1886 there have appeared

five other lives of Brown,

the most important being that of Richard

J. Hinton, who in his

preface glories in holding a brief for

Brown and his men. The

present volume is inspired by no such

purpose, but is due to

a belief that fifty years after the

Harper's Ferry tragedy the

time is ripe for a study of John Brown,

free from bias, from

the errors in taste and fact of the mere

panegyrist and from the

blind prejudice of those who can see in

John Brown nothing but

a criminal. The pages that follow were

written to detract from

or champion no man or set of men, but to

put forth the essential

truths of history as far as

ascertainable, and to judge Brown,

his followers and associates in the

light thereof."

There can be no doubt that Mr. Villard

labored

assiduously to bring his book up to the

high standard set

190

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

forth above. His bibliography of

manuscripts, books,

documents and papers consulted covers

twenty royal

octavo pages of closely printed matter

- a list of refer-

ences so complete that it will probably

not be extended.

In dealing with the character of John

Brown he most

seriously criticises the warfare waged

by him in Kansas

prior to 1857. He especially condemns

what he terms

"Murder on the Pottawatomie"

as without provocation

or extenuating cause. There are other

portions of the

book that attest pretty clearly the

declaration of the

author that he is not holding a brief

for John Brown.

Like his grandfather Garrison, Mr.

Villard finds it

difficult to justify the taking of

human life or participa-

tion in deeds of bloodshed and

violence. While he seeks

to be rigidly just and to take into

account the spirit of

the times in which John Brown lived,

his task is not

an easy one and his conclusions invite

criticism. When

John Brown appealed to arms and

ruthless warfare

against the ruffian invaders, violence

was manifest in

legislative halls, on the plains of

Kansas and wherever

the burning question of slavery had

divided the people

into hostile parties. While Villard

finds much to criti-

cise in John Brown's eulogists, in the

concluding chapter

of his book entitled "Yet Shall He

Live," he pays just

tribute to the heroic qualities that

Brown manifested

while in prison and when with

triumphant step he

mounted the scaffold and took his place

among the

martyrs of history. The conclusion of

his exhaustive

study is presented in the last four

sentences of his book:

"And so, wherever there is battling

against injustice and

oppression, the Charlestown gallows that

became a cross will help

men to live and die. The story of John

Brown will ever con-

front the spirit of despotism, when men

are struggling to throw

John Brown 191

off the shackles of social or political

or physical slavery. His

own country, while admitting his

mistakes without undue pal-

liation or excuse, will forever

acknowledge the divine that was

in him by the side of what was human and

faulty, and blind

and wrong. It will cherish the memory of

the prisoner of

Charlestown in 1859 as at once a sacred,

a solemn and an inspir-

ing American heritage."

In no other part of the United States,

perhaps, has

there been more controversy over the

subject of this

sketch than in the state of Kansas.

Here he first ap-

pealed to arms and here his friends

claim that he struck

the first telling blow which turned

back the tide of Pro-

Slavery invasion and ultimately made

Kansas a free

state.

When the war was on in the Territory of

Kansas

between the Free-State men and the

Border Ruffians

from Missouri and the South, the

settlers who were

opposed to slavery compromised their

differences and

fought shoulder to shoulder to make

Kansas free.

When they had triumphed and Kansas took

her place in

the Union without slavery, divisions

began to spring up

among the Free State men themselves,

divisions which

present the phenomenon not infrequently

witnessed of

factional differences in a triumphant

party after a polit-

ical campaign. Governor Robinson led

one of the Free

State factions, General Lane and the

followers of John

Brown united in another. The

controversy raged over

the question as to who had done most to

save Kansas to

freedom. The conflict was fanned to

furious heat

through political campaigns that

followed the Civil

War. Of course neither John Brown nor

his sons were

present to take part in the

controversy, but the friends

and enemies of Robinson and Lane waged

with each

other a long and bitter war of words,

the echoes of

192 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

which come down to the present time.

Governor Rob-

inson became one of the wealthiest men

in Kansas and

it was asserted by his opponents not

only that he had

acquired his wealth unjustly but that

he never hesitated

to use it to advance his interests in

the acrimonious con-

tests that he waged. As an outgrowth of

this contro--

versy we have a life of John Brown

written by William

Elsey Connelley, a well known historian

and at present

Secretary of the Kansas Historical

Society. After a

careful survey of the Kansas field,

Connelley took his

place in the ranks of the friends of

John Brown. While

in his biography he admits the

imperfections and mis-

takes of the hero of Black Jack and

Osawatomie, he

finds upon careful investigation

extenuating circum-

stances that go far toward justifying

all that John

Brown did in Kansas. He stoutly defends

the "Potta-

watomie executions" and quotes

eminent men to sustain

his view. Among those quoted are

Senator John J.

Ingalls* and Professor L. Spring,+ of

the University

of Kansas.

The appearance of Mr. Connelley's book

stirred up

Governor Robinson and his friends who

raised many

questions in regard to the authority of

the work and

rather severely criticised the author

because of the con-

* Senator Ingalls, in the North

American Review, of February,

1884, wrote: "It was the 'blood and

iron' prescription of Bismarck. The

Pro-Slavery butchers of Kansas and their

Missouri confederates learned

that it was no longer safe to kill. They

discovered, at last, that nothing

is so unprofitable as injustice. They

started from the guilty dream to

find before them, silent and tardy, but

inexorable and relentless, with up-

lifted blade, the awful apparition of

vengeance and retribution."

+ On the Pottawatomie affair Professor

Spring wrote: "Was the

fanatic's expectation realized? Did the

event approve his sagacity? I

think there is but one answer to

questions like these. After all, the fanatic

was wiser than the philosopher. The

effect of this retaliatory policy in

checking outrages, in bringing to a

pause the depredations of bandits, in

staying the proposed execution of Free

State prisoners was marvelous."

John Brown 193

clusions that he had drawn from

the study of his subject

and the stirring times in which Kansas

was born. If

the critics thought that Connelley

would calmly submit

to their estimate of his work and be

silent, they were

seriously mistaken. Mr. Connelley

wields a trenchant

pen in dealing with the detractors of

John Brown. The

pamphlet in which he replied to their

criticisms bears

the title An Appeal to the Record. Those

who had at-

tacked him and his work assuredly

discovered when this

pamphlet of 130 pages appeared that

they had caught a

Tartar. He retaliated by holding up to

public condem-

nation Governor Robinson, G. W. Brown

and Eli

Thayer. Their private lives are brought

into serious

question by sweeping general condemnations

and with

the promise to furnish detailed

particulars for the in-

dictment if occasion requires. Their

public records are

excoriated so mercilessly that their

friends to this day

must feel their blood tingle as they

peruse the pages of

the Record. His critics must

have felt when this publi-

cation appeared much as did those of

Byron when they

read English Bards and Scotch

Reviewers.

There appears never to have been a

reply to the in-

dignant "appeal," but its

appearance was probably re-

sponsible for the publication in 1913

of a volume entitled

"John Brown, Soldier of

Fortune, A Critique," by Hills

Peebles Wilson. This work is the most

condemnatory

that has been published on John Brown.

It scoffs at his

religious pretense, questions whether

Brown ever really

desired to liberate the slaves and

hurls anathemas at all

of his biographers who have said a word

in his support.

The author, however, gives Brown the

credit of having

carefully planned the Harper's Ferry

raid which in his

opinion almost succeeded. He scouts the

contention that

Vol. XXX - 13.

194

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

he was insane. At the climax of his

tirade he denounces

Brown as "Grafter! Hypocrite! Fiend!

MONSTER!"

In the closing pages of his book he

declares that Brown

was "crafty in the sublimest

degree of the art." He

concludes his "critique" of

407 pages with these lines,

quoting as a text the caption of the

final chapter in Vil-

lard's book:

" 'Yet Shall He Live': but it will

be as a soldier of fortune,

an adventurer. He will take his place in

history as such; and

will rank among adventurers as Napoleon

ranks among marshals;

as Captain Kidd among pirates; and as

Jonathan Wild among

thieves."

Assuredly here is fierce denunciation.

This book for

a time was read with much satisfaction

by the critically

inclined who place a low estimate upon

humanitarian

endeavor and reluctantly accord

unselfish motives to

others. Mr. Wilson places much stress

on the word

"grafter" throughout his

work.

This book was widely circulated; but

the effort thus

to blacken the name of Brown in history

came to a some-

what ignominious end. The widow of

Governor Rob-

inson, in the spirit of her husband,

continued the war-

fare against the friends of Lane and

Brown. Shortly

after she died Wilson appealed for the

money due him

for writing the book. He had to produce

his contract

in court to get his pay. This he did,

took the contract

price, $5000, and at latest reports was

no longer a citizen

of Kansas. This revelation detracted

from the influence

of the book and took much of the sting

out of "grafter"

and other epithets that the author so

liberally hurled at

old John Brown.

Peace now seems to reign among the

history writers

John Brown 195

of Kansas, with Connelley and his

friends triumphant

and the fame of John Brown again in the

ascendant.

There is a life of John Brown by W. E.

B. DuBois,

the colored scholar and author, which

is well worth

reading. It may be regarded as an index

of the ultimate

attitude of the race for which Kansas

bled and the gal-

lows of Virginia ushered in the tragic

drama of the

Civil War. DuBois's book does credit to

himself and

his people. It reflects their gratitude

for liberation from

bondage, and the estimate of Brown's

followers who

fought to accomplish this is thoughtful

and conserva-

tive. It is evident, however, that the

author has in mind

the present and future of his race and

a somber appre-

ciation of prejudices to be overcome

and wrongs to be

righted. He insists that the negro

still suffers grievous

injustice; that the times call for

another John Brown

to batter down the walls and break the

fetters that de-

prive his people of the rights and

opportunities which

should be theirs under our

institutions. He has a

grievance to present and a purpose to

accomplish; he

gets a hearing through his ably written

biography of

John Brown, even as Charles Sumner in

his scholarly

lecture on Lafayette found an avenue

for an attack on

the institution of slavery.

John Brown appears to have appealed

strongly to

literary men of other lands. Victor

Hugo, perhaps the

greatest writer of his age, himself an

exile at the time

of the raid, was quick to express

eloquent appreciation.

Later he joined with French republican

associates in

striking a gold medal for the widow of

John Brown and

sending it to her with the remarkable

letter which is

found elsewhere in this issue of the QUARTERLY.

Dr.

196

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Hermann von Hoist, the gifted and

cultured German,

who came to the United States and

attained eminence

as a historian of our institutions, has

left a tribute to

Brown in an extended essay which was

brought out in

a separate publication by Frank Preston

Stearns in

1889.

There are other biographies and

monographs; there

are pamphlets and periodical articles

almost without

number. Reference to the foregoing

works is made for

the convenience of the average reader

who may wish to

know something of the books that will

most likely be

within his reach, their authors and the

purpose for which

each was written.

In this connection it may be worth

while to bear in

mind that the writer of this

contribution and others that

are in contemplation was born and

reared under Quaker

influences and that as he writes memory

frequently

reverts to a Quaker grandfather who,

like others of his

faith, was valiant in the war of words

against the insti-

tution of slavery but deplored the

shedding of blood and

the clash of arms that came as the

result of the agitation.

His sympathy with Brown was heightened

by the fact

that two Quaker boys from a neighboring

farm went to

Harper's Ferry and one of them followed

his chief to

the gallows at Charlestown. The story

of this youth,

his tragic fate and the outpouring of

people to attend his

funeral is still rehearsed in the

little community where

Edwin Coppoc was born and near which

his mortal

remains are at rest. If bias marks

aught that is here

written, may it be credited to the

influence of those fire-

side memories.

Any adequate estimate of the character

and career of

John Brown should, of course, take into

consideration

John Brown 197

the record and spirit of the times in

which he lived.

This seems to be conceded by all who

have seriously

written on the subject and they have

collected and pub-

lished materials that make unnecessary

extended addi-

tional research. Mr. Villard in his

exhaustive work has

stated in consecutive order the

cumulative offenses on

both sides of the controversy over

slavery. It is difficult

to read these without reaching the

conclusion that deeds

of violence and the bloody sequel of

Civil War were

inevitable. In the light of what he

himself has written,

some of his judgments against John

Brown's operations

in Kansas may seem unduly severe. To

anti-slavery

settlers conditions had become

intolerable. Reprisals

and retribution were the results.

A review of the long controversy over

slavery need

not be presented here. It is sufficient

to know that when

Brown and his sons went to Kansas

hostile thoughts

were finding expression in action -

that violent words

were emphasized by cruel blows - that

heated appeals

from the rostrum were marshalling the

hosts for ensan-

guined battle fields.

Years before this in the state of

Illinois Lovejoy

had been shot while defending his right

through his

paper to oppose slavery, and for a

similar offense Gar-

rison had been mobbed in the streets of

Boston. It is

difficult for the rising generation to

understand that

men are still living who can remember

the raid of anti-

slavery newspapers, even in Ohio, and

the treatment of

at least one editor to a liberal coat

of tar and feathers.

As early as 1830 the condition of

affairs in Kentucky

was set forth in a message of the

governor of that state

in which he declared that "men

slaughter each other

almost with impunity" and urged the

legislature to take

198 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

action to prevent a condition that made

Kentucky still

the "dark and bloody ground."

John Quincy Adams

was denounced for his anti-slavery

utterances and this

toast was offered at a southern

banquet: "May we never

want * * * a hangman to prepare a

halter for

John Quincy Adams." On more than

one occasion the

pistol and the bowie knife were

brandished in the Con-

gress of the United States and

Pro-Slavery newspapers

put a price on the heads of their

eminent opponents:

"Five thousand dollars for that of

William H. Seward

and ten thousand dollars for the

delivery in Richmond

of Joshua R. Giddings," the

representative in Congress

of the Ohio Western Reserve, the homeof

John Brown

and his family.

The Pro-Slavery men who rushed to

Kansas in order

to fix upon it their "peculiar

institution," were not less

violent than the extremists of the

states from which

they came. Before John Brown reached

the Territory

it had been the scene of strife and

bloodshed over the

question of slavery. The invasion from

Missouri and

the South was in full sway. His sons

who had preceeded

him were already involved in the

controversy. They

were outspoken in their attitude of

hostility to slavery.

John Brown, Jr., on June 25, 1855, was

chosen vice-

president of the Free State Convention

held in Lawrence

on that day. He was on the committee

that reported

among other resolutions one containing

this "defy" to

the Missourians: "In reply to the

threats of war so fre-

quently made in our neighbor state, our

answer is, 'WE

ARE READY'." For this attitude the Browns were

"marked men," long before

their father appeared on the

scene.

At previous elections the state had

been overrun by

John Brown 199

Missourians, and the most flagrant

frauds had been

openly perpetrated. At the election for

delegate to Con-

gress November 29, 1854, they cast 1729

fraudulent

votes. In one district where the census

three months

later showed only 53 voters, 602 votes

were cast and

counted. At the election of members of

the Territorial

Legislature, March 30, 1855, this

outrage was even

more brazenly repeated. "Of 6307

votes cast, nearly

five-sixths were those of the

invaders." The Pro-

Slavery party by intimidation and

violence elected all

the members of the legislature except

one and he after-

ward resigned. This was the famous

Lecompton Legis-

lature which forced upon the people of

Kansas the Mis-

souri code, including the institution

of slavery.* It even

went farther and made it a criminal

offense for anyone

to entertain and express opinions

hostile to that

institution.

There had been a number of

"killings," how many

is not definitely known. Some who met

this fate are

specifically named in the report of the

Howard Congres-

sional Committee on which John Sherman,

of Ohio, was

a member. Others are reported, among

them the shoot-

ing of Charles Dow, a Free State man

from Ohio. Prac-

tically every person in Kansas went

armed and the seeds

of civil war were freely sown. The fact

that the Pierce

administration at Washington was doing

about every-

thing in its power to help fasten the

institution of slavery

on Kansas made the situation doubly

irritating for the

Free-State settlers. There was elected

by votes from

Missouri a sheriff of Lawrence County,

Kansas, who

at the same time held the position of

postmaster in

* This is the "Kansas

Legislature" referred to by John Brown in his

letter of February 20, 1856, to Joshua

R. Giddings.

200 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

Westport, Missouri. It is needless to say that this

sheriff was a source of trouble in this

stronghold of the

Free-State men.

The early part of the winter 1855-1856

passed rather

quietly. The Free State men were

gathering strength

and organizing for the admission of

Kansas without

slavery. Their convention adopted a

constitution and a

Free State legislature was chosen. John

Brown, Jr.,

was elected to the latter.+

On January 24, 1856, President Pierce

sent to Con-

gress a message that fanned to flaming

heat the resent-

ment of the Free State men. It

characterized their acts

in attempting to organize the state as

revolutionary and

likely to lead to "treasonable

insurrection." This mes-

sage was followed by a proclamation

placing the United

States troops at Fort Riley at the

service of Governor

Shannon, who was in complete sympathy

with the move-

ment to make Kansas a slave state. This

proclamation

foreshadowed the dissolution of the

Free State Topeka

Legislature by the military forces of

the United States.

The feelings that this aroused in John

Brown are fully

revealed in the following letter to

Joshua R. Giddings,

then representing the Western Reserve

District of Ohio

in Congress:

OSAWATOMIE, KANSAS TERRITORY, 20th Feby,

1856.

HON. JOSHUA R. GIDDINGS,

Washington, D. C.

DEAR SIR,

I write to say that a number of the

United States Soldiers

are quartered in this vicinity for the ostensible

purpose of re-

moving intruders from certain Indian Lands. It

is, however,

believed that the Administration has no thought of

removing

+ The Free State legislature was chosen

by the Free State party.

The Pro-Slavery party did not

participate in the election.

John Brown 201

the Missourians from the Indian Lands;

but that the real object

is to have these men in readiness to act

in the enforcement of

those Hellish enactments of the

(so called) Kansas Legislature;

absolutely abominated by a great

majority of the inhabitants of

the Territory; and spurned by them up to

this time. I con-

fidently believe that the next movement

on the part of the Ad-

ministration and its Proslavery masters

will be to drive the

people here, either to submit to those

Infernal enactments; or

to assume what will be termed treasonable

grounds by shooting

down the poor soldiers of the country

with whom they have

no quarrel whatever. I ask in the name

of Almighty God; I ask

in the name of our venerated

fore-fathers; I ask in the name of

all that good or true men ever held

dear; will Congress suffer

us to be driven to such "dire

extremities"? Will anything be

done? Please send me a few lines at this place. Long ac-

quaintance with your public life, and a

slight personal ac-

quaintance incline and embolden me to

make this appeal to

yourself.

Everything is still on the surface here

just now. Circum-

stances, however, are of a most

suspicious character.

Very respectfully yours,

JOHN BROWN.

This letter received prompt attention

at the hands of

the militant Congressman who replied in

part:

"You need have no fear of the

troops. The President will

never dare employ the troops of

the United States to shoot the

citizens of Kansas. The death of the

first man by the troops

will involve every free state in your

own fate. It will light up

the fires of Civil War throughout the

North, and we shall stand

or fall with you. Such an act will also

bring the President so

deep in infamy that the hand of political

resurrection will never

reach him."

On the day that Brown wrote the letter

to Joshua R.

Giddings, February 20, 1856, The

Squatter Sovereign

said editorially:

"In our opinion the only effectual

way to correct the evils

that now exist is to hang up to the

nearest tree the very last

traitor who was instrumental in getting

up, or participating in,

the celebrated Topeka Convention."

202 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

More than a month previous the

Pro-Slavery men

had acted in the spirit of this advice.

Captain Reese P.

Brown (not related to the subject of

this sketch) shortly

after he had been elected a member of

the Topeka Free-

State Legislature, was brutally

murdered by Pro-

Slavery men who rushed around him and

"literally

hacked him to death with their

hatchets." When his

bleeding body, from which life was not

yet extinct, was

thrown at the feet of his wife she

swooned and awoke

a raving maniac. The morning following

this deed The

Kansas Pioneer came out with this lurid appeal:

"Sound the bugle of war over the

length and breadth of

the land and leave not an abolitionist

in the territory to relate

their treacherous and contaminating

deeds. Strike your piercing

rifle balls and your glittering steel

to their black and poisonous

hearts."

The killing of Reese P. Brown was

scarcely more

gruesome than others occurring about

the same time.

It is here given because the victim was

elected to the

Topeka Legislature in which John Brown,

Jr., later

(March 8, 1856) acted on a committee

that condemned

the "cold blooded murder" of

their fellow member.

For his activity in this Legislature,

John Brown, Jr.,

was made to pay a terrible penalty as

will be shown later

in a sketch of his life. From the

little that has here been

said it may be seen that the subversion

of the ballot-box

was complete and that violence was rife

in Kansas be-

fore the affair at the Pottawatomie.

In the meantime the war of words on the

hustings

and in legislative halls was not less

violent than deeds

on the plains of Kansas. At times it is

difficult to say

which was echo of the other. In

Congress the speeches

turned more and more upon the struggle

to fix slavery

John Brown

203

on Kansas Territory and the parties to

the fray on that

western frontier were stirred to more

desperate action

by the charges and counter-charges,

denunciations and

appeals of their friends back east.

Excitement went up to fever heat when

Preston

Brooks, a member of the House of

Representatives from

South Carolina, accompanied by a

colleague from that

state and one from Virginia, made a

violent attack upon

Charles Sumner, a senator from the

state of Massachu-

setts. Sumner on the 19th day of May,

1856, delivered

a notable speech in the Senate in which

he most severely

arraigned the slave power and its

defenders in Congress.

He was eloquent in his defense of the

Free State settlers

of Kansas and contrasted their spirit

with that exhibited

by the people of South Carolina. He

compared the

women of Lawrence with "the

matrons of Rome who

poured their jewels into the treasury

for the public

defense":

"It would be difficult to find

anything in the history of

South Carolina," said he,

"which presents as much heroic spirit

in an heroic cause as shines in that

repulse of the Missouri in-

vaders by the beleaguered town of

Lawrence, where even the

women gave their effective efforts to freedom."

And in conclusion, turning to Senator

Butler, he

said:

"Ah, sir, I tell the senator that

Kansas, welcomed as a free

state, 'a ministering angel shall be' to

the Republic, when South

Carolina, in the cloak of darkness which

she hugs, 'lies howling'."

There were bitter personalities

exchanged in the

course of this debate. Two days

afterward Brooks of

South Carolina with his two

confederates approached

Sumner where he was sitting at his desk

in the senate

chamber. As he raised his cane he

shouted to Sumner,

204

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

"I have read your speech over

twice carefully; it is a

libel on South Carolina and Mr. Butler

who is a relative

of mine." With these words he

rained blow upon blow

upon Sumner's head and arms. The

senator struggled

to rise, but before he could

successfully defend himself

he fell bleeding from more than twenty

wounds on the

floor of the senate chamber. Senator Crittenden of

Kentucky started to assist Sumner but

was prevented by

Representative Keitt, of South

Carolina, Representative

Edmundson, of Virginia, and others who

shouted:

"Let them alone." "Don't

interfere." "Go it, Brooks."

"Give the Abolitionist h-l."

With shouts like these, in-

terspersed with oaths, the senate

chamber rang as the

confederates of Brooks with raised

canes prevented any

interference.

The subsequent history of this outrage

is too well

known to be repeated here. For almost four years

Sumner was unable to return to the

Senate.

The news of this disgraceful affair

reached John

Brown's men on their way to the

Pottawatomie. It

spurred them on to action swift and

terrible. The blows

struck in the Senate of the United

States reached to

Kansas - and farther. The memory of the

Sumner

assault is revived here simply to show

the unfortunate

condition into which the whole country

had drifted as

a result of the anti-slavery

controversy. When such

a deed of violence could occur in broad

daylight in the

highest legislative body of our land,

what might not be

expected, under the then existing

conditions, when the

news of it reached the Kansas frontier?

Shortly after the Pottawatomie tragedy

and before

authentic account of it had reached the

East, Abraham

Lincoln caught the spirit of the hour

and in his famous

John Brown 205

speech at Bloomington, Illinois, May

29, 1856, pro-

claimed:

"We must highly resolve that Kansas

must be free * * *

let us draw a cordon so to speak around

the slave states, and the

hateful institution, like a reptile poisoning itself,

will perish

by its own infamy."

He reached the climax in this speech in

these words:

"There is a power and a magic in

popular opinion. To

that let us now appeal; and while, in

all probability, no resort

to force will be needed, our moderation

and forbearance will

stand us in good stead when, if ever, we

must make an appeal

to battle and the God of hosts."

Quotations might be extended almost

without limit

to show that the spirit of war was in

the air throughout

our land when the first red drops of

the approaching

storm were falling on the plains of

Kansas.

The affair for which John Brown has

been most fre-

quently and seriously criticised was

preceded, it should

always be remembered, by the burning

and sacking of

the town of Lawrence, the headquarters

of the Free

State men in Kansas territory. To

avenge wrongs done

the "highly honorable Jones"

who was at the same time

holding the position of postmaster of

Westport, Mis-

souri,and sheriff of Lawrence County,

Kansas, a band

of border ruffians numbering about 1200

and led by

former United States Senator Atchison

of Missouri

appeared before the town. The citizens

determined to

offer no resistance and to put up to

the authorities of the

United States the responsibility for

what might follow.

After they had surrendered Atchison in

a fiery speech

said to his followers among other

things:

"And now we will go with our highly

honorable Jones, and

test the strength of that damned Free

State Hotel. Be brave,

206

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

be orderly, and if any man or woman

stand in your way, blow

them to hell with a chunk of cold lead."

The border ruffians, many of whom were

inflamed

by drink, sacked the town, destroyed

two newspaper

offices and threw the types, papers,

presses and books

into the river. A number of cannon

shots were then

fired into the Free State Hotel which

was soon on fire

and went up in flames. When it lay in

ruins the "highly

honorable Jones" shouted in glee:

"This is the happiest

moment of my life. I have done it, by

God I have done

it."

It has been sometimes claimed that John

Brown was

in Lawrence at the time its destruction

began. This is

hardly true, however, as there would

have been resolute

resistance if he had been there. Some

of his friends

have claimed that what he saw at

Lawrence was his

excuse for the act of vengeance on the

Pottawatomie,

but Villard marshals a lot of evidence

to show that John

Brown was probably not present and that

therefore he

could not offer what he saw in excuse

for what he later

did. It seems very inconsequential

whether he was

present or not. He certainly heard of

what occurred on

the 21st of May before the action of

his followers on the

Pottawatomie on the night of the 24th

of that month.

And the conclusion cannot be escaped

that he and his

followers, with this fresh

demonstration that the gov-

ernment of the United States would do

nothing to pre-

serve life and the semblance of

civilization in Kansas,

resolved to take the law into their own

hands and by a

terrible reprisal notify the Border

Ruffians that hence-

forth they would send their hordes into

Kansas at their

own peril, that their armed assassins

coming over the

John Brown 207

border would, in the language of

Corwin, "be welcomed

with bloody hands to hospitable

graves."

The Pottawatomie affair, as Villard

states, has

caused perhaps more discussion than any

other event in

the history of Kansas Territory. Upon

this the enemies

of John Brown invariably dwell at

length, while his

friends are equally explicit with their

apologies and

defenses. Five Pro-Slavery men were

killed on the

night of May 24, 1856, and it is now

generally admitted

that they met their fate at the hands

of John Brown and

his followers. John Brown himself

killed no one, it is

claimed, but he was present and later

assumed full re-

sponsibility for what was done. John

Brown, Jr. was

some distance away and did not learn of

the tragedy

until some time after it had occurred.

Colonel Richard

J. Hinton in his John Brown and His

Men fully justifies

what was done and terms it the

"Pottawatomie execu-

tions." Villard strongly condemns

the participants in

what he terms the "Murder on the

Pottawatomie."

The five Pro-Slavery men on

Pottawatomie Creek

were seized without warning and

ruthlessly slain. Full

particulars are given by Villard,

Sanborn and Hinton.

Although this action is strongly condemned

by Villard,

in his analysis of the motive of Brown,

he says:

"He believed that a collision was

inevitable in the spring,

and Jones and Donaldson proved him to be

correct. Fired with

indignation at the wrongs he witnessed

on every hand, impelled

by the Covenanter's spirit that made him

so strange a figure

in the nineteenth century, and believing

fully that there should

be an eye for an eye and a tooth for a

tooth, he killed his men

in the conscientious belief that he was

a faithful servant of

Kansas and of the Lord. He killed not to

kill, but to free; not

to make wives widows and children

fatherless, but to attack on

its own ground the hideous institution

of human slavery, against

which his whole life was a protest. He

pictured himself a

208

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

modern crusader as much empowered to

remove the unbeliever

as any armored searcher after the

Grail."

Villard also states that the action of

John Brown

on the Pottawatomie was generally

approved in after

years by the Free State men of Kansas

and that many of

them went on record to the effect that

it was necessary

for the protection of the Free State

settlers and prepared

the way for the final deliverance of

Kansas from the

institution of slavery.

In this introductory paper no attempt

will be made

to differentiate the conscientious

convictions that the

North and the South brought to the

controversy. At this

late day no serious effort will be

made, it is presumed, to

prove that the institution of slavery

was fundamentally

right and that it should have been

perpetuated under our

flag. At the time of John Brown's

activity in the anti-

slavery cause, however, the people of

the South believed

that their "peculiar system"

could be justified on the

highest moral grounds and their

ministers of the gospel

eloquently defended it from the pulpit,

basing their con-

clusions on extended quotations from

Holy Writ. An

overwhelming majority of the white

citizens of the

United States who lived south of the

Mason and Dixon

line regarded the abolition movement as

an attack upon

them and their property, designed to

incite a servile in-

surrection with horrors similar to

those that signalized

the uprising of the blacks against

their masters in San

Domingo. In view of this fact, the

excesses of the slave

power and its agents in Kansas and

Virginia are self-

explanatory.

The action of the people of Virginia at

Harper's

Ferry and Charlestown has been

criticised, ridiculed and

John Brown 209

bitterly condemned. The treatment of

the prisoners

who were captured at Harper's Ferry,

however, stands

out in redeeming relief. The jailer,

Captain Avis, and

Sheriff Campbell were so considerate

that the prisoners

paid frequent tribute to their kind and

chivalrous con-

duct. Much must be said also to the

credit of Governor

Wise whose testimony to the high

character and sterling

qualities of John Brown was truly

remarkable when we

consider the circumstances under which

it was uttered.

It must also be remembered that he was

so impressed

by the conduct of Edwin Coppoc and his

Quaker

friends that he desired to commute the

sentence of this

youth to imprisonment for life and was

only dissuaded

by action of the Legislature of

Virginia. In spite of

the excitement attending the raid and

the excesses inci-

dent to its suppression Virginia

maintained and exhib-

ited a degree of her traditional

chivalry.

Elsewhere will be presented a statement

of the won-

derful change in popular opinion that

was wrought in

large measure by John Brown and his

men. The Civil

War soon followed and the leaders who

were prominent

in opposing John Brown by force of arms

at Harper's

Ferry to maintain the supremacy of the

laws of the

United States and Virginia were soon

afterwards them-

selves in uniforms of gray fighting to

overthrow the

Republic that they had sworn to defend;

while the fol-

lowers of John Brown who survived the

raid and the

gallows were in uniforms of blue

fighting to preserve

the Union.

Of special importance, as we have

already intimated,

to all readers of the QUARTERLY is

Ohio's relation to the

work of John Brown and his men. Brown

himself

came to the village of Hudson, "the

capital of our West-

Vol. XXX - 14.

210

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

ern Reserve," when he was only

five years old and grew

up to manhood with the pioneers of our

state. Of seven

sons that aided him in his warfare

against slavery six

were born in Ohio and all were reared

in this state. Of

other followers John Henri Kagi, who

was killed at

Harper's Ferry, was born in Trumbull

County, Ohio,

and Edwin Coppoc, who was executed at

Charlestown,

Virginia, was born in Columbiana

County, Ohio, as was

his brother Barclay who escaped from

Harper's Ferry

and afterwards lost his life while

serving his country as

lieutenant in a Kansas regiment of

volunteers.

Lewis Sherrard Leary, who was killed at

Harper's

Ferry, and John A. Copeland, who was

executed at

Charlestown, were both colored, born in

other states but

Ohioans by adoption, and went from

their homes in

Oberlin to join John Brown at

Chambersburg, Pennsyl-

vania.

Wilson Shannon and Samuel Medary at

different

times served as governor of Kansas

Territory. The

former was appointed by President

Pierce and the latter

by President Buchanan. Both were from

Ohio and

had been prominent in the political

annals of this state.

Shannon had been its governor.

Other Ohio men less prominent were not

less pow-

erful in shaping the destiny of Kansas

in the days of

stress and controversy over

slavery. They were so

numerous that they were the dominating

influence in

the convention that gave Kansas her

free constitution.

The census of 1860 shows that Ohio had

at that time

contributed more than any other state

to the population

of Kansas.

One of the men who at Harper's Ferry

plied old John

Brown with questions for the evident

purpose of impli-

John Brown 211

eating prominent anti-slavery statesmen

in the raid,

was Clement L. Vallandigham, the

congressman from

Ohio, destined himself to lose the road

to eminence in

the mighty conflict soon to follow.

One of the youthful followers of Brown,

as will later

be seen, lost his life through the

burning of a bridge by

Quantrill, the Confederate guerrilla

chieftain, who was

also born in Ohio. Assuredly in this labyrinth of

tragedy Ohioans were conspicuously involved.

CHIEFLY BIOGRAPHICAL

Biographies of John Brown properly and

necessarily

start with Plymouth Rock. His ancestor,

Peter Brown

the carpenter, came over in the Mayflower

with the Pil-

grims in December, 1620.

Detailed information is available in a

number of

works relative to the descendants of

this ancestor. It is

unnecessary to repeat here all that has

been written.

Peter Brown died in 1633 and his

remains were buried

at Duxbury near those of the famous

Captain Standish

whose monument now rises from the

little promontory

that faces the sea.

Peter Brown of the Mayflower left

a son named

after himself who moved to Windsor,

Connecticut,

shortly prior to 1658. He here became

the father of

thirteen children, one of whom, John

Brown, was born

January 8, 1668. He grew to manhood and

was the

father of eleven children, one of whom,

John Brown

second, was born in 1700 and died in

1790. His son, Cap-

tain John Brown of West Simsbury, was

the grandfather

of John Brown of Osawatomie and

Harper's Ferry

fame. This grandfather was a soldier in

the Revolution

and died in the service, leaving a

widow and eleven chil-

212

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

dren, one of whom was born after he

entered the army.

This widow's maiden name was Owen and

one of her

sons named Owen was the father of John

Brown,

the militant opponent of slavery. A

detailed account of

his ancestry shows that Welsh, Dutch

and English blood

mingled in his veins. Both of his

grandfathers were

officers in the Revolution and one of

them, as we have

seen, died in the service.

Owen Brown lived for a time in the town

of West

Simsbury, now Canton, Connecticut.

"Town" is used

here in the New England sense and means

township.

Later he moved to Torrington,

Connecticut, where his

son John was born May 9, 1800. In 1804

he made a

journey to what was then the far West

and visited Hud-

son, Ohio, with the thought of locating

there. One year

afterward he brought his family in a

wagon drawn by

an ox team, chose his place of

habitation and became a

citizen of the young state, Ohio.

The maiden name of John Brown's mother

was

Ruth Mills. Her father, Lieutenant Gideon Mills,

moved to Ohio in 1800, five years

before Owen Brown

and his family came to the state.

Fortunately for those interested, Owen

Brown when

nearly eighty years old and while

living at Hudson

wrote a biography covering rather fully

the events of

his life. This autobiography has a

general interest for

the reader as it details the

experiences, the trials, re-

verses and triumphs of the pioneers of

our state and

especially those who came over from

Connecticut and

settled on the Western Reserve. This

brief narrative is

taken up largely with the things that

interested the

average emigrant from the East who

settled in this

section. Much of it is devoted to

family interests, the

John Brown 213

record of the births and deaths of

numerous children,

the pursuits of the pioneers, efforts

to get the merest

rudiments of an education and the

religious experiences

which made up a prominent part of the

history of Hud-

son and the surrounding country.

Omitting the larger portion of this

autobiography be-

cause it is readily accessible in The

Life and Letters of

John Brown by F. B. Sanborn, we here quote some of

the paragraphs that relate especially

to that portion of

the life of Owen Brown that was spent

in Ohio:

"We arrived in Hudson on the 27th

of July, and were re-

ceived with many tokens of kindness. We

did not come to a

land of idleness; neither did I expect

it. Our ways were as pros-

perous as we had reason to expect. I

came with a determination

to help build up and be a help, in the

support of religion and

civil order. We had some hardships to

undergo, but they appear

greater in history than they were in

reality. I was often called

to go into the woods to make division of

lands, sometimes sixty

or seventy miles from home, and be gone

some weeks, sleeping

on the ground, and that without serious

injury.

"When we came to Ohio the Indians

were more numerous

than the white people, but were very

friendly, and I believe were

a benefit rather than an injury. In

those days there were some

that seemed disposed to quarrel with the

Indians, but I never

had those feelings. They brought us

venison, turkeys, fish, and

the like; sometimes they wanted bread or

meal more than they

could pay for at the time, but were

always faithful to pay their

debts. In September, 1806, there was a

difficulty between two

tribes; the tribe on the Cuyahoga River

came to Hudson, and

asked for assistance to build them a

log-house that would be a

kind of fort to shelter their women and

children from the fire-

arms of their enemy. Most of our men

went with teams, and

chopped, drew, and carried logs, and put

up a house in one day,

for which they appeared very grateful.

They were our neigh-

bors until 1812, but when the war commenced with the British,

the Indians left these parts mostly, and

rather against my

wishes."

A glimpse of what the second war with

England

meant to this pioneer community may be

had from the

following quotation:

214

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

"In July, 1812, the war with

England began; and this war

called loudly for action, liberality,

and courage. This was the

most active part of my life. We were

then on the frontier, and

the people were much alarmed,

particularly after the surrender

of General Hull at Detroit. Our cattle,

horses, and provisions

were all wanted. Sick soldiers were

returning, and needed all

the assistance that could be given them.

There was great sick-

ness in different camps, and the travel was mostly

through Hud-

son, which brought sickness into our

families. By the first of

1813 there was great mortality in

Hudson. My family were

sick, but we had no deaths."

John Brown inherited his opposition to

slavery.

This is clearly set forth in a statement

by his father

written about 1850:

"I am an abolitionist. I know we

are not loved by many;

I have no confession to make for being

one, yet I wish to tell

how long I have been one, and how I

became so. I have no

hatred to negroes. When a child four or

five years old, one

of our nearest neighbors had a slave

that was brought from

Guinea. In the year 1776 my father was

called into the army

at New York, and left his work undone.

In August, our good

neighbor, Captain John Fast, of West Simsbury, let my

mother

have the labor of his slave to plough a

few days. I used to go

out into the field with this slave, -

called Sam, - and he used

to carry me on his back, and I fell in

love with him. He worked

but a few days, and went home sick with

the pleurisy, and died

very suddenly. When told that he would

die, he said that he

should go to Guinea, and wanted victuals

put up for the journey.

As I recollect, this was the first

funeral I ever attended in the

days of my youth. There were but three

or four slaves in West

Simsbury. In the year 1790, when I lived

with the Rev. Jere-

miah Hallock, the Rev. Samuel Hopkins,

D. D., came from

Newport, and I heard him talking with

Mr. Hallock about slav-

ery in Rhode Island, and he denounced it as a great

sin. I

think in the same summer Mr. Hallock had

sent to him a sermon

or pamphlet-book, written by the Rev. Jonathan Edwards,

then

at New Haven. I read it, and it denounced slavery as a

great

sin. From this time I was anti-slavery,

as much as I be now."

In 1857 when John Brown was in the midst

of war-

fare against slavery and stationed at

Red Rock, Iowa,

he wrote in fulfillment of a promise a

sketch of his life

John Brown 215

for Henry L. Stearns, a boy only

thirteen years old.

The occasion of the writing of this

sketch was the grat-

itude of Brown to Mr. George Luther

Stearns, a

wealthy merchant and manufacturer of

Boston whom

Brown visited shortly after Christmas

in 1856. Stearns

had a beautiful home at Medford and

here he enter-

tained his guest, with whose

anti-slavery views he was

in cordial sympathy. The oldest son of

the family was

much interested in Brown and gave him

some money

that he had been saving to buy shoes

for "one of those

little Kansas children." When

Brown left the boy ex-

acted from him a promise that he would

write the story

of his boyhood days. This he did later

at Red Rock,

Iowa, and sent it to the Stearns family.

The manuscript

is still in existence. It has been

published many times

and we quote from it simply within the

limitations of

what may especially interest Ohio

readers. He speaks

of the long journey to Ohio which he

distinctly remem-

bered, always referring to himself in

the third person:

"When he was five years old his

father moved to Ohio,

then a wilderness filled with wild

beasts and Indians. During

the long journey, which was performed

in part or mostly with an

ox team, he was called by turns to

assist a boy five years older,

who had been adopted by his father and

mother."

It is rather remarkable that no

difference how large

these pioneer families were they always

seemed to have

room for additions by adoption. The

doors were usually

open to a child or youth for varied

periods of time as

we shall see later. Again Brown in

speaking of his

coming to Ohio says:

"After getting to Ohio in 1805 he was

for some time rather

afraid of the Indians and their rifles, but this soon

wore out and

he used to hang about them quite as much as was

consistent with

good manners and learned a trifle of

their talk."

216

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

He then proceeds to tell how he learned

the tanner's

trade under the direction of his father

and to detail his

youthful experiences, his association

with Indian chil-

dren and his fondness for pets. Of

schooling he re-

ceived very little. He says:

"Indeed when for a short time he

was sometimes sent to

school, the opportunity it afforded to

wrestle and snowball and

run and jump and knock off old seedy

wool hats offered him al-

most the only compensation for the

confinement and Restraints

of school."

As he grew older larger responsibilities

came to him

and he drove cattle, sometimes a

distance of a hundred

miles. His experiences at this period

are the founda-

tions from which Elbert Hubbard built up

much of his

interesting novel, Time and

Chance. As set forth in

that story, Zanesville, Ohio, was the

destination of this

boy herdsman. We quote from what he has

to say in

regard to the war with England, as he saw

it, and the

influences that made him a foe to

slavery:

"When the war broke out with

England, his father soon

commenced furnishing the troops with

beef cattle, the collecting

and driving of which afforded him some

opportunity for the

chase (on foot) of wild steers and other

cattle through the

woods. During this war he had some

chance to form his own

boyish judgment of men and measures and

to become somewhat

familiarly acquainted with some who have

figured before the

country since that time. The effect of

what he saw during the

war was to so far disgust him with

military affairs that he would

neither train or drill but paid fines

and got along like a Quaker

until his age finally has cleared him of

military duty.

"During the war with England a

circumstance occurred that

in the end made him a most determined

abolitionist and led him

to declare or swear eternal war with

slavery. He was staying

for a short time with a very gentlemanly

landlord, since a United

States Marshal, who held a slave boy

near his own age, very

active, intelligent and good feeling and

to whom John was under

considerable obligation for numerous

little acts of kindness. The

master made a great pet of John, brought him to table

with his

John Brown 217

first company and friends, called their

attention to every little

smart thing he said or did and to the fact of his being

more

than a hundred miles from home with a

company of cattle alone,

while the negro boy (who was fully if

not more than his equal)

was badly clothed, poorly fed and lodged

in cold weather and

beaten before his eyes with iron shovels or any other

thing that

came first to hand. This brought John to

reflect on the wretched,

hopeless condition of fatherless and

motherless slave children,

for such children have neither fathers

or mothers to protect and

provide for them. He sometimes would

raise the question, is

God their Father?"

Of his early religious experiences he

says:

"John had been taught from earliest

childhood to 'fear God

and keep His commandments;' and though

quite skeptical he

had always by turns felt much serious

doubt as to his future

well being and about this time became to

some extent a convert

to Christianity and ever after a firm

believer in the divine authen-

ticity of the Bible. With this book he

became very familiar and

possessed a most unusual memory of its

entire contents."

Again he reverts to his work at Hudson.

He says:

"From fifteen to twenty years old,

he spent most of his

time at the tanner and currier's trade,

keeping bachelor's hall

and he officiating as cook and for most

of the time as foreman

in the establishment under his

father."

While this youth was working in his

father's tan-

nery, another boy by the name of Jesse

Grant, whose

parents had come from Connecticut to

Pennsylvania

and later to Ohio, came to the Brown

home and was

admitted to the family. He and young

John Brown

worked side by side daily and became

much attached to

each other. Little did either dream of

the future before

him. John was to become the father of

sons who should

give their lives in an effort to

overthrow the institution

of slavery, and Jesse was to become the

father of the

general who should lead armed hosts to

bind the states

closer together and make freedom

universal in America.

218

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Ulysses S. Grant, the son of Jesse, in

his memoirs com-

pleted at Mt. McGregor July 1, 1885,

has this to say of

his father's apprenticeship in the

tannery of Owen

Brown:

"He went first, I believe, with his

half-brother, Peter Grant,

who, though not a tanner himself, owned

a tannery in Maysville,

Kentucky. Here he learned his trade, and

in a few years re-

turned to Deerfield and worked for, and lived in the

family of

a Mr. Brown, the father of John

Brown-'whose body lies

mouldering in the grave, while his soul goes marching

on.' I

have often heard my father speak of John

Brown, particularly

since the events at Harper's Ferry.

Brown was a boy when

they lived in the same house, but he

knew him afterwards, and

regarded him as a man of great purity of

character, of high

moral and physical courage, but a

fanatic and extremist in what-

ever he advocated. It was certainly the

act of an insane man

to attempt the invasion of the South,

and the overthrow of

slavery, with less than twenty

men."

In the War of 1812, Owen Brown

contracted to fur-

nish beef to Hull's army, which with

his boy John he

followed to or near Detroit. Though

John was but

twelve years old, in after years he

recalled very dis-

tinctly the incidents of the long

march, the camp life of

the soldiers and the attitude of the

subordinate officers

toward their commander. From

conversations that he

overheard he concluded that they were

not very loyal to

General Hull. He remembered especially

General Lewis

Cass, then a captain, and General

Duncan McArthur.

As late as 1857 he referred to

conversations between the

two and among other officers that

should have branded

them as mutineers. How much of this has

foundation

in fact and how much is due to

erroneous youthful im-

pression, must of course remain a

matter of conjecture.

Like most children of his day John

Brown had very

meager educational opportunities at

Hudson. He sup-

John Brown 219

plemented the rudiments that he there

acquired in the

schools and the church by reading such

standard books

as Eosop's Bables, Life of Franklin and

Pilgrim's

Progress.

At the age of sixteen years he joined

the Congre-

gational Church at Hudson and later

thought seriously

of studying for the ministry. With this

purpose in

view he returned to Connecticut and

entered a prepar-

atory school at Plainfield, intending

later to take a course

at Amherst College. Inflammation of his

eyes, how-

ever, prevented him from continuing his

studies and he

soon returned to Hudson. Later at odd

moments he

studied surveying and attained skill

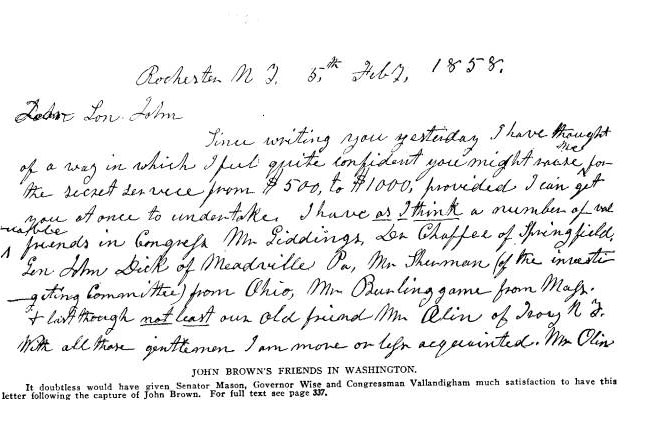

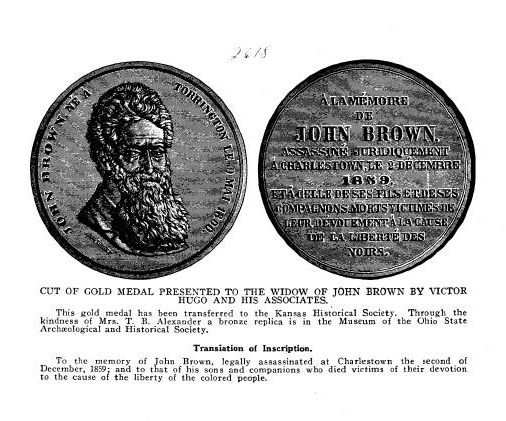

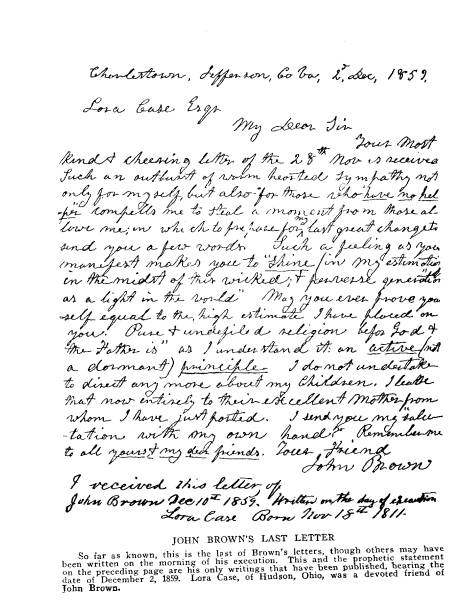

and accuracy in its